Abstract

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) is a rare epithelial-like soft tissue sarcoma. The two main sites of its occurrence are the lower extremities in adults and the head and neck in children. Primary pulmonary involvement of this sarcoma, without evidence of soft tissue tumor elsewhere, is very exceptional. We present a case of primary ASPS of the lung in a 42-yr-old woman. A computed tomographic scan of the thorax demonstrated a well-circumscribed, solid tumor located in the right upper lobe. The mass was resected by right upper lobectomy. After 5 months, three metastatic lesions, involving lumbar vertebrae and occipital scalp, were found. Histologically, the tumor consisted of alveolar nests of large polygonal tumor cells, the cytoplasm of which frequently revealed periodic acid-Schiff-positive, diastase-resistant intracytoplasmic rod-like structures. On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells were positive only for vimentin and alpha-smooth muscle actin. Ultrastuctural study using electron microscopy revealed characteristic electron-dense, rhomboid intracytoplasmic crystals.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Alveolar Soft Part; Lung

INTRODUCTION

Alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS) is a distinct, rare soft tissue tumor with unknown histogenesis and a tendency for late widespread metastases to lung, bone and brain. Morphologically, its classic feature consists of a proliferation of large polygonal cells arranged in a prominent alveolar pattern. The tumor cells show the characteristic periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive, diastase-resistant, intracytoplasmic crystals that appear as rhomboid or rectangular cytoplasmic crystals on electron microscopy. Clinically, the tumor most commonly arises in the fascial planes or skeletal muscles of the lower extremities in adults, and in the head and neck region in children (1). However, isolated cases of ASPS arising in the viscera have also been occasionally documented (2). We report here a unique case of primary lung ASPS occurring in a 42-yr-old Korean woman without evidence of a primary soft tissue tumor elsewhere at the time of initial diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the third report of such cases appearing in the English literature since the mid 1960's.

CASE REPORT

A 42-yr-old woman was referred to us for further evaluation of an asymptomatic mass in the right upper lobe of the lung. She was a non-smoker and had no previous illnesses, except for a right thyroid nodule noticed about two years earlier. A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the thorax demonstrated a 4.2×3.4 cm, well-circumscribed, solid tumor in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe (Fig. 1). Further extensive radiological examinations, including brain and abdominal CT scans, abdominal ultrasonography, and 99mTcmethylene diphosphonate bone scan, were performed. No extrapulmonary lesions other than a thyroid mass were seen. A right upper lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection was performed.

Fig. 1.

The computed tomographic scan demonstrates a well-circumscribed tumor located in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe of the lung.

Examination of the right upper lobe revealed a firm, gray white, circumscribed tumor that measured 3.8×3.5×3.5 cm and was located subpleurally. Adjacent lung tissue was unremarkable except for mild emphysematous changes. The pleura and regional lymph nodes were grossly free of tumor. On light microscopic examination, the tumor was composed predominantly of nests of large polygonal tumor cells, with central discohesive areas assuming an alveolar appearance (Fig. 2). In some areas, a trabecular arrangement, reminiscent of hepatocellular carcinoma, was also noted. The individual tumor cells had vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm was abundant, eosinophilic, and finely granular. On the whole, mitoses were scarce. When stained with PAS staining, the tumor cells frequently revealed PAS-positive, diastase-resistant intracytoplasmic granules or rod-like structures (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor cells were focally positive for both vimentin and alpha-smooth muscle actin (Fig. 4), but were negative for cytokeratin 7, epithelial membrane antigen, thyroid transcription factor-1, thyroglobulin, S100 protein, CD56, desmin, and myoglobin. The electron microscopic study using the formalin-fixed lung tumor specimen identified characteristic electron-dense rhomboid intracytoplasmic crystals in the tumor cells (Fig. 5). However, ultrastructural features of skeletal muscle differentiation, such as the presence of sarcomeric contractile structures, were absent.

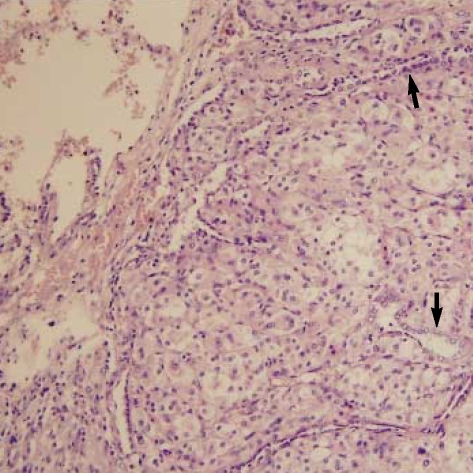

Fig. 2.

The tumor shows characteristic alveolar nests of large polygonal tumor cells. Emphysematous lung tissue is found in the left upper corner, and arrows indicate bronchioles entrapped within the tumor mass (hematoxylin-eosin, ×200).

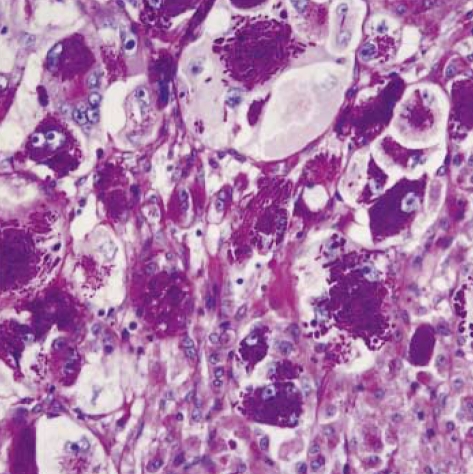

Fig. 3.

Periodic acid-Schiff preparation with diastase digestion highlights the distinctive intracytoplasmic granules or rod-like structures in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells (D-PAS, ×400).

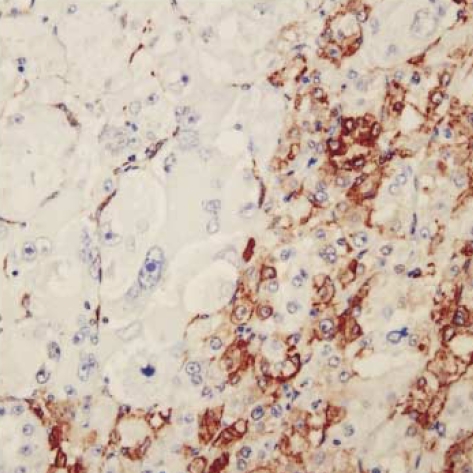

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical stain for alpha-smooth muscle actin demonstrates a focally positive reaction in the tumor (SMA immunostain, ×400).

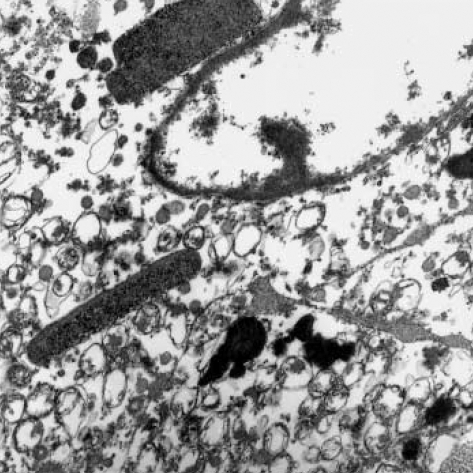

Fig. 5.

Electron microphotograph shows electron-dense rhomboid intracytoplasmic crystals in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells (×8,000).

Two months after the surgery, thyroidectomy for the thyroid nodule was performed, and the pathologic diagnosis was papillary thyroid carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine, performed at 5 months post lobectomy, revealed two lobulated osteolytic masses, 2.5 cm and 1.8 cm in diameter, in the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, respectively. Histologically, the bony masses proved to be metastatic alveolar soft part sarcomas (Fig. 6). The patient underwent palliative radiotherapy (total 30 cGy) locally to the lower back. She then received three courses of chemotherapy with a combination of mesna, actinomycine, ifosfamide, and dacarbazine. During the chemotherapy, a small cutaneous nodule, 1.0 cm in diameter, was noted in the right occipital scalp. The nodule was also confirmed to be metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma following an excisional biopsy.

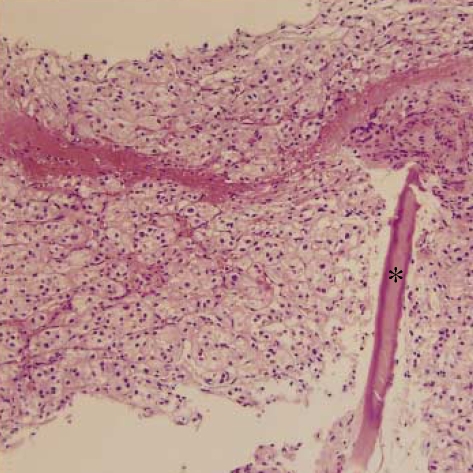

Fig. 6.

Metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma involving the lumbar vertebrae shows the same histologic features as the primary lung tumor. An asterisk indicates a piece of destroyed bony spicule (hematoxylin-eosin, ×200).

The patient has been followed up for 25 months since the lung surgery without any evidence of further metastatic disease.

DISCUSSION

ASPS commonly presents as a slow-growing and painless mass, usually without functional impairment, but it is known to be highly malignant. In a number of cases, vein invasion was commonly seen, and blood-borne metastases appeared in the lungs and other organs as long as 30 yr or more following excision of the primary tumor. Not infrequently, a metastasis in the lung or in another organ may be the first manifestation of the disease (3). Therefore, when the tumor is detected in visceral organs, other than soft tissues, it is mandatory to perform a thorough clinicoradiogic evaluation before establishing the final diagnosis. We recently experienced a case of primary pulmonary ASPS without any evidence of soft tissue tumor elsewhere at the time of initial diagnosis. A search of the PubMed (National Library of Medicine) database between 1966 and 2005, revealed two similar cases (4, 5), primarily involving the lung, one of which was written in French. Concerning the exact anatomical location, however, the Japanese case written in English by Tsutsumi and Deng (4) was described as being a tumor arising from the pulmonary vein at the level of the lung hilus. Thus, we suspect that their case originated in the mediastinum rather than in the lung. In Korea, Kim et al. (6) recently reported three cases of presumably primary ASPS of the lung. Their cases, pathologically diagnosed by mass excision or percutaneous needle biopsy, showed a radiological presentation of multiple nodules in the bilateral lung fields or diffuse pulmonary consolidation. Considering that primary soft tissue ASPS commonly occurs as a single mass (1), we presume that the presentation pattern of those Korean cases is very unusual.

Morphologically, ASPS can mimick renal cell carcinoma, paraganglioma, and hepatocelllular carcinoma, in that they share nested and alveolar patterns of growth bounded by prominent sinusoidal vasculature (2). However, if well-formed PAS-positive, diastase-resistant intracytoplasmic granules or crystals that are characteristic of ASPS can be demonstrated, the differential diagnosis is usually not very difficult. Cytoplasmic granules, sometimes with a crystalline appearance, are a classical histological feature of ASPS. The typical ASPS crystals seem to form within these cytoplasmic dense granules that are PAS-positive and diastase-resistant (6).

The cellular origin of ASPS is still elusive. Over the past half a century, the debate on the cellular lineage of this tumor has focused primarily on the possibilities of myogenic, Schwann cell or paraganglial histogenesis (7). A recent study (8) using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using cDNAs from MyoD1 and myogenin genes postulated that ASPS is of skeletal muscle origin. In the present case, however, the tumor developed in the lung where skeletal muscle is normally absent. The tumor cells were focally immunoreactive to alpha-smooth muscle actin but did not demonstrate any positivity to other myogenic markers such as desmin, MyoD1, or myoglobin. Furthermore, there was no ultrastructural evidence indicative of myogenic differentiation. Thus, it seems that the findings from our case do not support a myogenic origin of ASPS. The molecular genetic pathogenesis of ASPS was recently elucidated and was shown to be due to a translocation between chromosome 17q25 and Xp11, resulting in a fusion product between TFE3 (a transcription factor gene) on chromosome Xp11 and a novel gene designated as ASPL on chromosome 17q25 (9). These cytogenetic and molecular findings were promising, but the hope that the approach might shed a light on its histogenesis was dashed by the observation that neither of ASPL or TFE3 shows a tissue- specific expression pattern (10).

In conclusion, despite numerous immunohistochemical and electron microscopic studies a debate on the histogenesis of ASPS has continued over the past half a century. Moreover, it seems that the ambiguity of its histogenesis has been complicated even more by its exceptional occurrence in skeletal muscle-free tissues, the lung, as in the case described in this report.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Medical Research Institute Grant (2004-40), Pusan National University, Busan, Korea.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc; 2001. pp. 1509–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman PH, Brennan MF, Kimmel M, Erlandson RA, Garin-Chesa P, Flehinger BY. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma. A clinico-pathologic study of half a century. Cancer. 1989;63:1–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890101)63:1<1::aid-cncr2820630102>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lillehei KO, Kleinschmidt-De Masters B, Mitchell DH, Spector E, Kruse CA. Alveolar soft part sarcoma. An unusually long interval between presentation and brain metastasis. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:1030–1034. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90121-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsutsumi Y, Deng YL. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the pulmonary vein. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1991;41:771–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1991.tb03350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devisme L, Mensier E, Bisiau S, Bloget F, Gosselin B. Alveolar sarcoma. Report of a case. Ann Pathol. 1996;16:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim NR, Lee MS, Yoon YC, Kim DS, Lee KS, Suh GY, Kim JG, Han JH. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the lung-A report of six cases and clinicopathological analysis. Korean J Pathol. 2003;37:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ordonez NG. Alveolar soft part sarcoma: a review and update. Adv Anat pathol. 1999;6:125–139. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano H, Tateishi A, Imamura T, Miki H, Ohno T, Moue T, Sekiguchi M, Unno K, Abe S, Matsushita T, Katoh Y, Itoh T. RT-PCR suggests human skeletal muscle origin of alveolar soft-part sarcoma. Oncology. 2000;58:319–323. doi: 10.1159/000012119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladanyi M, Lui MY, Antonescu CR, Krause-Boehm A, Meindl A, Argani P, Healey JH, Ueda T, Yoshikawa H, Meloni-Ehrig A, Sorensen PH, Mertens F, Mandahl N, van den Berghe H, Sciot R, Cin PD, Bridge J. The der(17)t(X;17)(p11;q25) of human alveolar soft part sarcoma fuses the TFE3 transcription factor gene to ASPL, a novel gene at 17q25. Oncogene. 2001;20:48–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argani P, Antonescu CR, Illei PB, Lui MY, Timmons CF, Newbury R, Reuter VE, Garvin AJ, Perez-Atayde AR, Fletcher JA, Beckwith JB, Bridge JA, Ladanyi M. Primary renal neoplasms with the ASPL-TFE3 gene fusion of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a distinctive tumor entity previously included among renal cell carcinomas of children and adolescents. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:179–192. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]