Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the impact of obesity on the posto-perative outcome after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Data from 328 consecutive patients with primary HCC and 60 patients with recurrent HCC were studied. We compared the surgical outcomes between the non-obese group (body mass index: BMI < 25 kg/m2) and the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2).

RESULTS: Following curative hepatectomy in patients with primary HCC, the incidence of postoperative complications and the long-term prognosis in the non-obese group (n = 240) were comparable to those in the obese group (n = 88). Among patients with recurrent HCC, the incidence of postoperative complications after repeat hepatectomy was not significantly different between the non-obese group (n = 44) and the obese group (n = 16). However, patients in the obese group showed a significantly poorer long-term prognosis than those in the non-obese group (P < 0.05, five-year survival rate; 51.9% and 92.0%, respectively).

CONCLUSION: Obesity alone may not have an adverse effect on the surgical outcomes of patients with primary HCC. However, greater caution seems to be required when planning a repeat hepatectomy for obese patients with recurrent HCC.

Keywords: Body mass index, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatectomy, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Obesity, the incidence of which has recently been growing at an epidemic rate in Japan[1], as well as in the other Western countries, has been implicated as a risk factor for postoperative complications in general surgery[2–4]. Indeed, several studies have shown that obesity increases the risk of wound complications in various types of surgical procedure[5]. However, the effects of obesity on surgical outcomes remain controversial[6–8].

The World Health Organization (WHO)[9] defines obesity as a body mass index (BMI) above 30 kg/m2, but in Japan, the prevalence of the population with such a BMI is no more than 2%-3%, in contrast to the 20%-30% prevalence in Western countries[10]. In Japan, the definition of obesity is proposed to be a BMI above 25 kg/m2, since the incidence of obesity-related disorders increases with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2[1,11]. On the other hand, recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated that obesity is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[12–14]. To our knowledge, however, there are no data regarding the postoperative outcomes in obese patients with HCC. Therefore, in the present study, we specifically evaluated the influence of obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) on the early and late surgical results following curative hepatic resection in Japanese patients with HCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 1995 to August 2006, 328 consecutive patients with HCC received a curative primary hepatic resection at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital. Sixty patients with intrahepatic recurrence, who underwent a curative repeat hepatectomy, were also examined. A curative hepatectomy indicates that no tumor remained in the remaining liver based on the findings of an intraoperative ultrasound examination or a computed tomographic (CT) study performed within 3 mo after surgery. Repeat hepatectomy for recurrent HCC was considered to be the treatment of choice for resectable recurrent tumors. Our selection criteria for repeat hepatectomy were the same as those for primary resection for HCC. The selection of type of hepatectomy was made on the basis of tumor location and liver function[15]. Patients with uncontrollable ascites are considered to be contraindicated for a hepatic resection. Therefore, no patients with ascites were included in this study. Height and weight were measured preoperatively, and the BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by squared height (m). Although the WHO[9] defines obesity as a BMI above 30 kg/m2, only 7 (2.1%) of the 328 patients with primary HCC and 1 (1.7%) of the 60 patients with recurrent HCC met this definition. Therefore, in the present study, we defined obesity as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2.

The records of 328 patients with primary HCC were reviewed retrospectively. These patients were classified into two groups based on BMI: an obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) group and a non-obese (BMI < 25 kg/m2) group. Similarly, the 60 patients with recurrent HCC were classified into two groups based on BMI. We compared clinicopathological parameters, such as liver function data, operative data, postoperative complications and tumor factors, between the obese group and the non-obese group. Postoperative complications were defined as any event that required specific medical or surgical treatment. We also compared the survival rates and disease-free survival rates between the two groups. All patients were closely followed after operation. Monthly measurements of alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II) were performed. Every 3 to 4 mo, ultrasonographic examination and dynamic CT were performed by radiologists. An angiographic examination was performed after admission when recurrence was strongly suspected.

Statistical analysis

To compare the clinicopathological variables between the two patient groups, either the unpaired Student’s t test or the chi-square test was used. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan and Meier method and the differences in survival between the groups were then compared using the log-rank test. Only a few significant variables were analyzed in the multivariate analysis using Cox's proportional hazard model. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Impact of obesity (BMI ≥ 25) on hepatectomy for primary HCC

Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathological variables of the patients in the non-obese (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 240: 73%) and obese groups (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 88: 27%). The percentage of female patients in the obese group was significantly higher than that in the non-obese group (P < 0.05). However, the percentage of patients with diabetes mellitus was not significantly different between the two groups. No differences were noted between the groups in terms of liver function data, operative data (such as operation time, blood loss and postoperative complications) or tumor factors. The incidence of postoperative infectious complications in the obese patients (7/88, 8.0%) tended to be higher (P = 0.092) than that in the non-obese patients (8/240, 3.3%). However, the incidence of other complications, such as intractable ascites and bile leakage, did not differ significantly between the two groups. In total, the incidence of postoperative complications in the obese group was comparable to that in the non-obese group (Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinicopathological data of nonobese (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a primary curative hepatectomy

| Variables | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 240) | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 88) | P value |

| Age | 65.6 ± 9.9 | 66.0 ± 8.8 | 0.725 |

| Gender (male:female) | 172:68 | 50:38 | < 0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.6 ± 2.2 | 27.1 ± 2.0 | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 23.1 | 25.3 | 0.684 |

| Positive HCV antibody (%) | 72.1 | 73.9 | 0.748 |

| Liver function data | |||

| AST (international units/L) | 54.8 ± 34.7 | 48.7 ± 24.0 | 0.132 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 0.307 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 87.2 ± 15.2 | 86.9 ± 15.4 | 0.881 |

| Child-Pugh class (A:B) | 222:18 | 83:5 | 0.210 |

| Operative data | |||

| Procedures (Hr0/HrS:Hr1/Hr2) | 159:81 | 57:31 | 0.752 |

| Operation time (min) | 208 ± 97 | 207 ± 80 | 0.886 |

| Blood loss (g) | 534 ± 526 | 582 ± 596 | 0.472 |

| Blood transfusion (%) | 13.3 | 18.2 | 0.730 |

| Postoperative complications (%) | 11.7 | 13.6 | 0.658 |

| Postoperative hospital death (%) | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.801 |

| Tumor factors | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.3 ± 2.4 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 0.337 |

| Solitary tumor (%) | 71.3 | 72.7 | 0.729 |

| Positive fc (%) | 69.3 | 60.7 | 0.152 |

| Positive vp (%) | 51.1 | 53.6 | 0.898 |

| Positive im (%) | 9.7 | 9.5 | 0.970 |

| Well/Moderately/Poorly1 | 39/170/20 | 13/58/8 | 0.933 |

| AFP (> 20 ng/mL) (%) | 52.7 | 50.6 | 0.730 |

BMI: Body mass index; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; AST: Aspartate transaminase; Hr0: Resection less than subsegmentectomy; HrS: Subsegmentectomy; Hr1: Segmentectomy; Hr2: Bisegmentectomy; fc: Capsular formation; vp: Invasion to portal vein; im, intrahepatic metastasis; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein.

Histologic differentiation of the tumor.

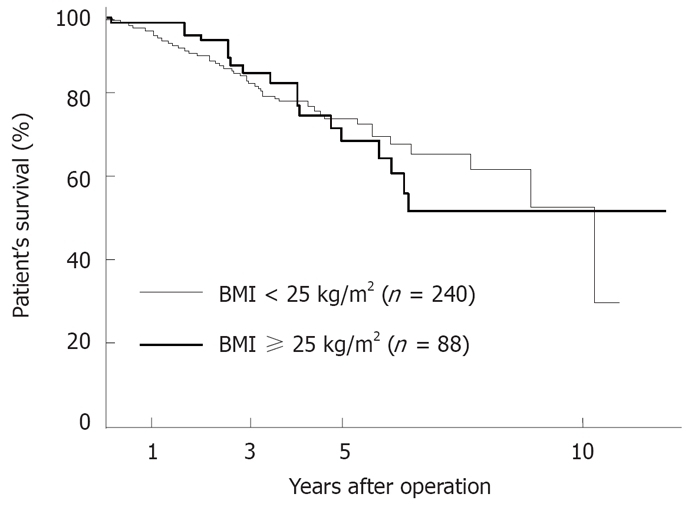

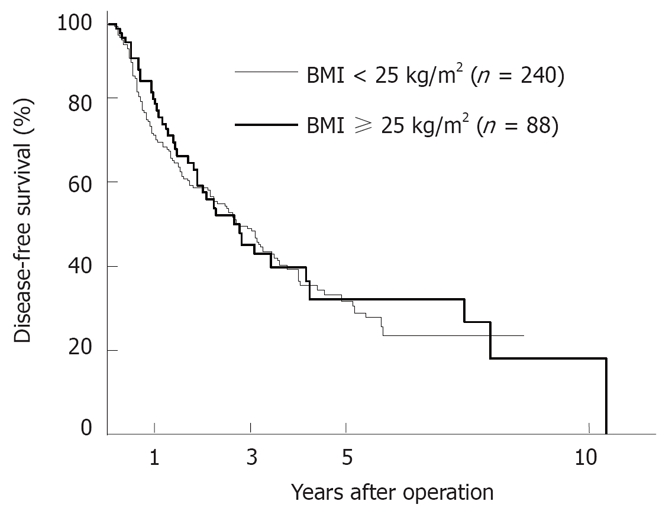

The survival of patients in the obese group was almost identical to that in the non-obese group (Figure 1). Moreover, no significant difference was found in the disease-free survival rates between the two groups (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the survival curves after a primary hepatectomy in the nonobese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 240) versus the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 88). The patient’s survival rate in the nonobese group did not differ significantly from that in the obese group.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the survival curves after primary hepatectomy in the nonobese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 240) versus the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 88). No significant difference in the disease-free survival rate between the two groups was observed.

Impact of obesity (BMI ≥ 25) on repeat hepatectomy for recurrent HCC

Table 2 compares the clinicopathological features between the non-obese (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 44: 73%) and obese groups (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 16: 27%). Similar to the patients with primary HCC (Table 1), there was a significantly higher proportion of female patients in the obese group than in the non-obese group (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the liver function data and tumor factors. However, the operation time was significantly longer (P < 0.05) and the blood loss was significantly greater (P < 0.01) in the obese group compared with the non-obese group. Although no statistically significant difference was noted, the patients in the obese group tended to receive blood transfusions more frequently than those in the non-obese group (P = 0.068). Four patients (25%) in the obese group had postoperative complications, which included intractable ascites in 2 cases, wound infection in 1 case and angina pectoris in 1 case. The incidence of postoperative complications did not differ significantly between the two groups, and no postoperative hospital death occurred after a repeat hepatectomy.

Table 2.

The clinicopathological data of nonobese (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a repeat hepatectomy

| Variables | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n = 44) | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n = 16) | P value |

| Age | 67.0 ± 10.3 | 67.7 ± 7.6 | 0.809 |

| Gender (male:female) | 32:12 | 7:9 | <0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.9 ± 2.0 | 26.9 ± 1.3 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 24.4 | 20 | 0.728 |

| Positive HCV antibody (%) | 70.5 | 80 | 0.463 |

| Liver function data | |||

| AST (international units/L) | 39.7 ± 24.7 | 46.8 ± 31.0 | 0.367 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 0.427 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 87.7 ± 13.3 | 83.6 ± 17.7 | 0.352 |

| Child-Pugh class (A:B) | 43:01:00 | 14:02 | 0.136 |

| Operative data | |||

| Procedures (Hr0/HrS:Hr1/Hr2) | 40:4 | 16:0 | 0.108 |

| Operation time (min) | 188 ± 68 | 243 ± 100 | <0.05 |

| Blood loss (g) | 453 ± 336 | 1044 ± 1120 | <0.01 |

| Blood transfusion (%) | 6.8 | 25 | 0.068 |

| Postoperative complications (%) | 9.1 | 25 | 0.128 |

| Postoperative hospital death (%) | 0 | 0 | 0.999 |

| Tumor factors | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.197 |

| Solitary tumor (%) | 72.3 | 81.3 | 0.491 |

| Positive fc (%) | 42.9 | 53.3 | 0.485 |

| Positive vp (%) | 42.9 | 53.3 | 0.307 |

| Positive im (%) | 11.9 | 0 | 0.073 |

| Well/Moderately/Poorly1 | 6/29/6 | 5/9/2 | 0.384 |

| AFP (> 20 ng/mL) (%) | 46.5 | 60 | 0.367 |

BMI: Body mass index; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; AST: Aspartate transaminase; Hr0: Resection less than subsegmentectomy; HrS: Subsegmentectomy; Hr1: Segmentectomy; Hr2: Bisegmentectomy; fc: Capsular formation; vp:Invasion to portal vein; im: intrahepatic metastasis; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein.

Histologic differentiation of the tumor.

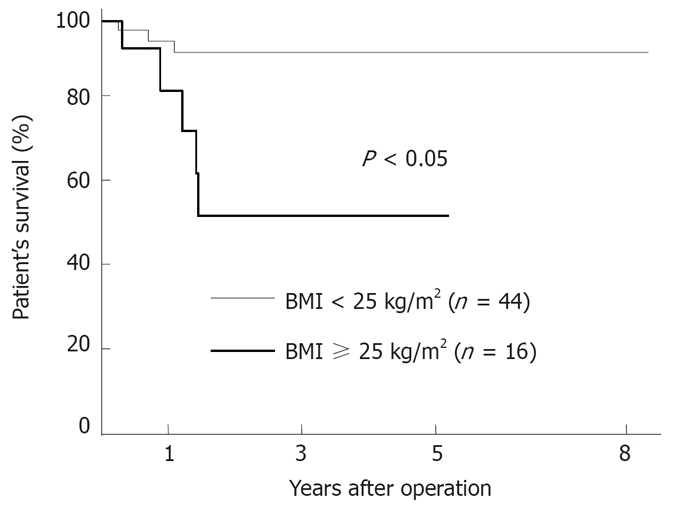

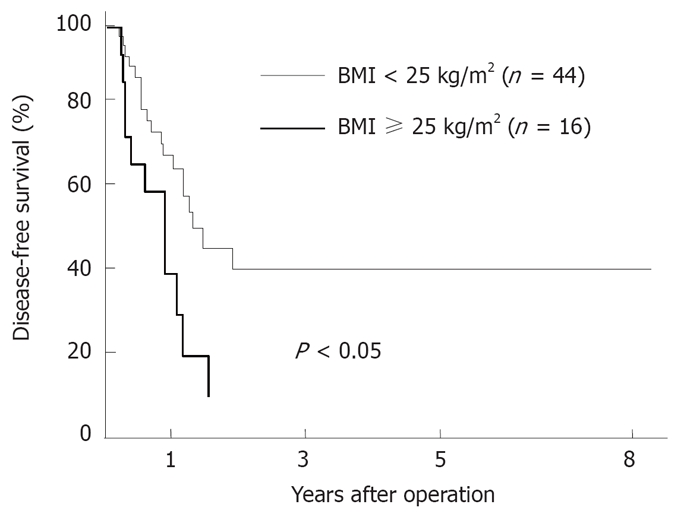

We also compared the cumulative survival rates, as shown in Figure 3. Patients in the obese group had a significantly poorer prognosis (P < 0.05) than those in the non-obese group. The disease-free survival rate in the obese group was also significantly lower than that in the non-obese group (P < 0.05; Figure 4). Nineteen of the 44 patients in the non-obese group and 11 of the 16 patients in the obese group had recurrent disease after repeat hepatectomy. Regarding the patterns of recurrence, 11 (58%) of the 19 patients in the non-obese group and 2 (18%) of the 11 patients in the obese group had a solitary intrahepatic recurrence. The remaining patients had a widespread recurrence, including multinodular recurrence in the remnant liver and/or extrahepatic recurrence. Therefore, patients in the obese group (9/11, 82%) showed widespread recurrences more frequently than those in the non-obese group (8/19, 42%) after a repeat hepatectomy.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the survival curves after repeat hepatectomy in the nonobese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 44) versus the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 16). The patient’s survival rate in the obese group was significantly lower than that in the nonobese group (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the survival curves after a repeat hepatectomy in the nonobese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2, n = 44) versus the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, n = 16). A significantly shorter disease-free survival was found in the obese group than in the nonobese group (P < 0.05).

In a univariate analysis, 3 variables were identified to be significant prognostic factors: obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), tumor size (≥ 2 cm) and microscopic presence of portal vein invasion. Furthermore, a multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazard model demonstrated obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) to be an independent prognostic indicator in patients with recurrent HCC (Table 3).

Table 3.

The results of a multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazard model in the patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a repeat hepatectomy

| Variables | Coefficient | SE | Relative risk | P value |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) | 0.770 | 0.372 | 2.160 | < 0.05 |

| Tumor size (≥ 2 cm) | 0.389 | 0.438 | 1.477 | 0.351 |

| Positive vp | 0.466 | 0.433 | 1.595 | 0.254 |

SE: Standard error; vp: Invasion to portal vein.

DISCUSSION

Obese patients are at an increased risk of numerous medical problems, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and immune dysfunction, which can adversely affect the surgical outcomes. However, several studies have investigated this issue and the results are still controversial, possibly due to the use of different definitions and classifications of obesity, and the lack of a uniform way of reporting surgical complications[16,17]. Dindo et al[6] studied the impact of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) on the outcomes of 6336 patients undergoing general elective surgery. They found that obesity alone was not a risk factor for postoperative complications. Since the association between BMI and health risks to Asian populations is different from that in European populations[11,18], we defined obesity as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 in this study. Consistent with the findings of a previous report[6], there was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative complications and postoperative hospital death between the non-obese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and the obese group (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), following curative hepatectomy in patients with primary HCC. On the other hand, among patients with recurrent HCC, the operation time and blood loss were significantly greater in the obese group than in the non-obese group. Since the operative procedures (extent of hepatic resection) were comparable between the two groups (Table 2), these data reflect the apparent greater technical difficulty of a repeat hepatectomy in obese patients. The wider area of peritoneal adhesion owing to the previous operation and the limited visualization of the surgical field in obese patients might adversely affect the operation time and blood loss. However, the difference in the incidence of postoperative complications after a repeat hepatectomy between the two groups did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, these results indicate that there exists no marked influence of obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) on the early surgical outcome after a curative hepatic resection, in both patients with primary HCC and those with recurrent HCC.

Only a few investigators have studied the impact of obesity on long-term outcomes following surgery, and the results are conflicting[3,19]. Dhar et al[3] suggested that being overweight was an independent predictor of disease recurrence in T2/T3 gastric cancers, whereas Kodera et al[19] reported that obesity did not affect long-term survival after a distal gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. In the current study, we found no remarkable impact of obesity on the long-term prognosis after a curative hepatectomy in patients with primary HCC. On the other hand, among patients with recurrent HCC, the long-term prognosis following repeat hepatectomy in the obese patients was significantly worse than that in the non-obese patients. Furthermore, obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) was an independent poor prognostic indicator in patients with recurrent HCC. The reason why obesity adversely affects the long-term outcome in these patients is not clear. However, several reports have suggested that obesity is significantly associated with a higher rate of death due to many cancers, including liver cancer[12,13,20,21]. In particular, recent studies have implicated that non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterized by obesity, can progress to liver cirrhosis and HCC[22–24]. However, pathological examinations in the resected non-cancerous liver specimens revealed only 4 of the 328 patients with primary HCC and one of the 60 patients with recurrent HCC to have NASH in this study. It therefore appears that the poorer prognosis after repeat hepatectomy in obese patients was not attributable to the progression of NASH. The mechanism generally proposed to explain the association between obesity and a worse prognosis include elevated concentrations of insulin-like growth factors[25], leptin[26], hormones[27] and cytokines[28]. Additional proposed mechanisms include reduced immune functioning and differences in diet and physical activity between obese and non-obese patients[20,21]. However, these mechanisms fail to explain the poorer prognosis after a repeat hepatectomy in the obese patients, because such a worse prognosis was not observed in obese patients with primary HCC. Among patients with recurrent HCC, those in the obese group showed a significantly greater amount of blood loss and tended to receive blood transfusions more frequently than those in the nonobese group. Many investigators have demonstrated that the increased blood loss and the need for blood transfusions are risk factors for recurrent HCC[29,30], which is attributed to the induction of immunosuppression. Therefore, the worsened prognosis in obese patients might be associated with the synergistic impacts of the obesity itself and perioperative blood transfusions due to increased blood loss on immune function.

In conclusion, our present findings suggest that the obesity, as defined by a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, does not have an adverse impact on postoperative outcomes, including postoperative complications and long-term prognosis, after a curative hepatectomy in patients with primary HCC. However, more caution seems to be required when planning a repeat hepatectomy for recurrent HCC in patients who are either overweight or obese.

COMMENTS

Background

Several studies have shown that obesity increases the risk for postoperative complications. However, the influence of obesity on the postoperative outcome after hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has never been evaluated.

Research frontiers

Recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated that obesity is a risk factor for HCC. Therefore, it is important to investigate not only the short-term outcome, but also the long-term outcome after hepatectomy in patients with HCC.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The long-term prognosis after curative resection for HCC remains unsatisfactory, because of a high rate of recurrence. Repeat hepatectomy has been established as the treatment of choice for recurrent HCC. However, our present findings suggest that more caution may be required when planning such a procedure for obese patients with recurrent HCC.

Applications

The authors would like to emphasize that the incidence of obesity-related disorders increases with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 in Japan. The prevalence of the population with such a BMI in Japan is almost identical to that of the population with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 in Western countries. This is the reason why we considered the definition of obesity used in this study to be reasonable. Therefore, it will be valuable to evaluate the impact of obesity on surgical outcomes following repeat hepatectomy in Western countries.

Terminology

The WHO defines obesity as a BMI above 30 kg/m2. However, in this study, we defined obesity as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, because of the reasons described above.

Peer review

I think it is an important paper that adds a great deal to the literature. There is not much on the topic. Your sample was large; the paper was nicely written; tables were well done and figures were very good. It was a pleasure to read.

Peer reviewers: Giovanni Tarantino, MD, Professor, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Federico II University Medical School, VIA S. PANSINI, 5, Naples 80131, Italy; Giulio Marchesini, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, “Alma Mater Studiorum” University of Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola, Via Massarenti 9, Bologna 40138, Italy; Laura E Matarese, MS, RD, LDN, FADA, CNSD, Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, UPMC Montefiore, 7 South, 3459 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, United States

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.McCurry J. Japan battles with obesity. Lancet. 2007;369:451–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benoist S, Panis Y, Alves A, Valleur P. Impact of obesity on surgical outcomes after colorectal resection. Am J Surg. 2000;179:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhar DK, Kubota H, Tachibana M, Kotoh T, Tabara H, Masunaga R, Kohno H, Nagasue N. Body mass index determines the success of lymph node dissection and predicts the outcome of gastric carcinoma patients. Oncology. 2000;59:18–23. doi: 10.1159/000012131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubo M, Sano T, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sasako M. Increasing body mass index in Japanese patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:39–41. doi: 10.1007/s10120-004-0304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro M, Munoz A, Tager IB, Schoenbaum SC, Polk BF. Risk factors for infection at the operative site after abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1661–1666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212303072701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dindo D, Muller MK, Weber M, Clavien PA. Obesity in general elective surgery. Lancet. 2003;361:2032–2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13640-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gretschel S, Christoph F, Bembenek A, Estevez-Schwarz L, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Body mass index does not affect systematic D2 lymph node dissection and postoperative morbidity in gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:363–368. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujinaka T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Sano T, Kurokawa Y, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, Katai H, Shimizu T, Furukawa H, et al. Influence of overweight on surgical complications for gastric cancer: results from a randomized control trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic D3 lymphadenectomy (JCOG9501) Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:355–361. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2001;286:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan. Circ J. 2002;66:987–992. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell SH, Crespo DM, Kang HS, Al-Osaimi AM. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S97–S103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh SW, Yoon YS, Shin SA. Effects of excess weight on cancer incidences depending on cancer sites and histologic findings among men: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4742–4754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian Y, Fan JG. Obesity, fatty liver and liver cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makuuchi M, Kosuge T, Takayama T, Yamazaki S, Kakazu T, Miyagawa S, Kawasaki S. Surgery for small liver cancers. Semin Surg Oncol. 1993;9:298–304. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980090404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leroy J, Ananian P, Rubino F, Claudon B, Mutter D, Marescaux J. The impact of obesity on technical feasibility and postoperative outcomes of laparoscopic left colectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;241:69–76. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150168.59592.b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gretschel S, Christoph F, Bembenek A, Estevez-Schwarz L, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Body mass index does not affect systematic D2 lymph node dissection and postoperative morbidity in gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:363–368. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodera Y, Ito S, Yamamura Y, Mochizuki Y, Fujiwara M, Hibi K, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A. Obesity and outcome of distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1225–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchini F, Kaaks R, Vainio H. Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:565–574. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McTiernan A. Obesity and cancer: the risks, science, and potential management strategies. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:871–881; discussion 881-882, 885-886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bugianesi E, Leone N, Vanni E, Marchesini G, Brunello F, Carucci P, Musso A, De Paolis P, Capussotti L, Salizzoni M, et al. Expanding the natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: from cryptogenic cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:134–140. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshioka Y, Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Kaneda H, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and burnt-out NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1215–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fassio E, Alvarez E, Dominguez N, Landeira G, Longo C. Natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a longitudinal study of repeat liver biopsies. Hepatology. 2004;40:820–826. doi: 10.1002/hep.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Madarnas Y, Hartwick W, Hoffman B, Hood N. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XJ, Yuan SL, Lu Q, Lu YR, Zhang J, Liu Y, Wang WD. Potential involvement of leptin in carcinogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2478–2481. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorincz AM, Sukumar S. Molecular links between obesity and breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:279–292. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chlebowski RT, Aiello E, McTiernan A. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1128–1143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makino Y, Yamanoi A, Kimoto T, El-Assal ON, Kohno H, Nagasue N. The influence of perioperative blood transfusion on intrahepatic recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1294–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu CC, Cheng SB, Ho WM, Chen JT, Liu TJ, P’eng FK. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:348–355. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]