Abstract

It was previously reported that the Korean predictive model could be used to identify patients at high risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). This study investigated whether PONV in the high-risk and very high-risk patients identified by the Korean predictive model could be prevented by multiple prophylactic antiemetics. A total of 2,456 patients were selected from our previous PONV study and assigned to the control group, and 374 new patients were recruited consecutively to the treatment group. Patients in each group were subdivided into two risk groups according to the Korean predictive model: high-risk group and very high-risk group. Patients in the treatment group received an antiemetic combination of dexamethasone 5 mg (minutes after induction) and ondansetron 4 mg (30 min before the end of surgery). The incidences of PONV were examined at two hours after the surgery in the postanesthetic care unit and, additionally, at 24 hr after the surgery in the ward, and were analyzed for any differences between the control and treatment groups. The overall incidence of PONV decreased significantly from 52.1% to 23.0% (p≤0.001) after antiemetic prophylaxis. Specifically, the incidence decreased from 47.3% to 19.4% (p≤0.001) in the high-risk group and from 61.3% to 28.3% (p≤0.001) in the very high-risk group. Both groups showed a similar degree of relative risk reductions: 59.0% vs. 53.8% in the high-risk and very high-risk groups, respectively. The results of our study showed that the antiemetic prophylaxis with the combination of dexamethasone and ondansetron was effective in reducing the occurrence of PONV in both high-risk and very high-risk patients.

Keywords: High-Risk Patients, Multiple Antiemetic Prophylaxis, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

INTRODUCTION

Despite the latest advances in anesthesia and the introduction of a new class of antiemetics, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is still one of the most common postoperative patient complaints. Generally, one-third of patients undergoing surgery are known to suffer from postoperative nausea, vomiting, or both, and often rate PONV as worse than postoperative pain (1). In addition, PONV, although being not common but serious in its nature, has been associated with various complications ranging from minor incisional pain to more severe hematoma, wound dehiscence, esophageal rupture, bilateral pneumothorax, and increased risk for aspiration. Furthermore, discharge from the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) may be delayed, and hospital admission (or readmission) in ambulatory patients often occurs due to PONV, which increases the overall medical cost (2).

Numerous antiemetic regimens, alone or in combination, have been used for treatment and tried for prophylaxis with some degree of effectiveness. However, routine prophylaxis is not recommended to all surgical patients because it may impose unnecessary side effects as well as increase the overall cost (3). Instead, selective prophylaxis in patients who are likely to have PONV, after identifying the most predictive risk factors, would offer much benefit resulting in improved satisfaction (4). Several studies have been carried out to identify the risk factors for PONV and develop risk models to calculate the probability of PONV (5, 6). Recently, the major predictive risk factors for PONV were identified through a large-scaled study in Korean population, and the Korean predictive model for PONV was developed. The following five risk factors in the order of relevance were reported to be strongly predictive of PONV: 1) female, 2) history of previous PONV or motion sickness, 3) duration of anesthesia more than 1 hr, 4) non-smoking status, and 5) use of opioids in the form of patient controlled analgesia (PCA). If none, one, two, three, four, or five of these risk factors were present, the reported incidence of PONV was 12.7%, 19.9%, 29.3%, 40.7%, 53.1 %, and 65.4%, respectively. The formula to calculate the probability of PONV using the multiple regression analysis was as follows: P (probability of PONV)=1/1+e-Z, Z=-1.885 +0.894 (gender)+0.661 (history)+0.584 (duration of anesthesia)+ 0.196 (smoking status)+0.186 (use of PCA-based opioid) where gender: female=1, male=0; history of previous PONV or motion sickness: yes=1, no=0; duration of anesthesia: more than 1 hr=1, less than or 1 hr=0; smoking status: no=1, yes=0; use of PCA-based opioid: yes=1, no=0. This model can be used to calculate the probability of PONV in order to administer prophylactic antiemetics in selected high-risk patients (7).

The most commonly studied combination of antiemetics is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist with either droperidol or dexamethasone with a similar degree of protective effects (8-11). However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has limited the use of droperidol because of its potential association with arrhythmia (12). Therefore, the most effective and safest combination regimen seems to be the one with 5-HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone. Ondansetron is known to have greater anti-vomiting than anti-nausea effects whereas dexamethasone has a stronger anti-nausea effect (2, 11). The aim of this study was to examine the prophylactic effect of combined ondansetron and dexamethasone with complementary superiority in anti-vomiting and anti-nausea effects, respectively, on the incidence of PONV in high-risk and very high-risk patients based on the Korean predictive model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all patients provided written informed consent. We recruited 2,456 patients as the control group from our previous predictive study (7). The combinations of strong predictive risk factors of PONV and the number of patients within each combination were ranked from highest to lowest according to the incidences of PONV. Next, we arbitrarily categorized this list into four groups, low or mild (<20%), moderate (20-40%), high (40-60%), and very high (>60%), and then selected a number of more commonly occurring combinations as reflected by the largest number of patients from high-risk and very high-risk groups. As a result, 1,623 patients were of high-risk, who were nonsmoking females without a history of PONV or motion sickness and their operations were longer than 1 hr with the postoperative opioid use not being counted. And 833 were very high-risk patients, nonsmoking females with a history of PONV or motion sickness with the other factors being the same. As the treatment group, 374 patients were consecutively enrolled in high-risk or very high-risk patients after identifying the same risk factors as the control groups, and they received intravenous injections of dexamethasone 5 mg, immediately after the induction of anesthesia and ondansetron 4 mg, 30 min before the end of surgery.

Anesthesia was induced intravenously using either thiopental (5 mg/kg) or propofol (2 mg/kg). Tracheal intubation was facilitated with neuromuscular blocking agents (vecuronium, 0.15 mg/kg or rocuronium, 0.8 mg/kg), which were repeated according to clinical needs. For maintenance, all patients received a balanced anesthetic technique with either volatile anesthetics (sevoflurane, enflurane, isoflurane, or desflurane; end tidal concentration 1-2 vol%) or propofol (50-200 µg/kg/min). Intraoperative opioids including fentanyl (2 µg/kg), morphine (0.1 mg/kg), or meperidine (0.5 mg/kg) were used in some patients. Nitrous oxide was used at the anesthesiologist's discretion. At the end of anesthesia, the patient's neuromuscular block was reversed with a combination of pyridostigmine 0.2 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.005 mg/kg upon the presence of four twitches under train-of-four stimulation.

The exclusion criteria included the administration of steroid, prior history of gastrointestinal disease, diabetics, patients transferred to ICU after surgery, and patients who were not able to communicate within 24 hr after surgery. An interviewer, who was blinded to the history of medication, assessed and examined the presence and severity of PONV at 2 and 24 hr after the surgery in the PACU and in the ward, respectively. Chlorpheniramine 4 mg was administered intravenously if the patient complained of PONV in the ward. Each patient was regarded as having PONV when she experienced any nausea and/or vomiting within the first 24 postoperative periods.

Prospective power analysis showed that to detect more than 50% decrease in the incidence of PONV in both high-risk group and very high-risk group due to the treatment, 1,623 and 222 high-risk patients and 833 and 152 very high-risk patients in control and treatment groups, respectively, would give more than 90% power with a significance level of 0.05. This is based on the data from our previous study that without the treatment, the incidences of PONV in high-risk and very high-risk groups are 47.4% and 61.3%, respectively.

A t-test was used to analyze the mean age and weight, and a Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze the duration of operation. A chi-square test was used to examine the PCA and intraoperative opioid uses, anesthetic agent, and the incidence of PONV. The effect of antiemetics in each group in comparison to the previous study is presented as RRR (Relative Risk Reduction). A p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

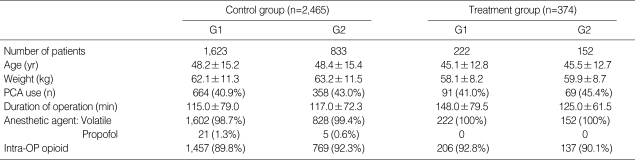

There were no differences between the high-risk and very high-risk groups of treatment and control groups with respect to age, weight, PCA use, duration of operation, anesthetic agent, and intraoperative opioid use (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of study patients

G 1, High-risk group; G 2, Very high-risk group; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; Intra-OP, intra-operation.

Values are expressed as Mean±SD. Data are number (%) of patients.

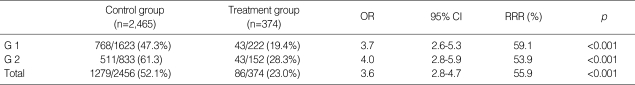

The overall incidence of PONV was significantly lower (p<0.05) in the treatment group (86 of total 374 patients, 23.0%) than in the control group (1,279 of total 2,456 patients, 52.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidences of PONV after antiemetic prophylaxis

PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; G 1, high-risk group; G 2, very high-risk group; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RRR, relative risk reduction.

In the high-risk groups, 43 of 222 (19.4%) patients in the treatment group and 768 of 1,623 (47.3%) patients in the control group complained of PONV, and the incidence of PONV was significantly lower in the treatment group (p<0.05). In the very high-risk groups, 43 of 152 (28.3%) patients in the treatment group and 511 of 833 (61.3%) patients in the control group developed PONV. Likewise, the incidence of PONV was significantly lower in the treatment group (p<0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to RRR: 59.0% in the high-risk group and 53.8% in the very high-risk group (Table 2).

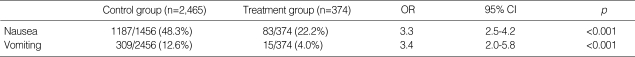

The incidences of nausea in the control and treatment groups were 48.3% (1187 patients) and 22.2% (83 patients), respectively. There was a significantly greater anti-nausea effect in the treatment group (p<0.05). Vomiting was observed in 12.6% (309 patients) and 4.0% (15 patients) in the control and the treatment groups, respectively. The incidence of vomiting was significantly reduced in the treatment group compared to the control group, but only a minor antiemetic effect was observed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidences of nausea and vomiting after antiemetic prophylaxis

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The data of our study clearly demonstrated that prophylactic administration of combined ondansetron and dexamethasone in the selective groups of high-risk and very high-risk patients was highly effective in decreasing the incidences of PONV from 47.4% and 61.3% to 19.4% and 28.3%, respectively.

It is now generally accepted that PONV is one of the most distressing side effects after anesthesia, with an incidence up to 70% of "high-risk" inpatients during the 24 hr postoperative period. The well established risk factors of PONV are female gender post-puberty, nonsmoking status, history of PONV or motion sickness, childhood after infancy and younger adulthood, increasing duration of surgery, use of volatile anesthetics, nitrous oxide, large-dose neostigmine, and intraoperative or postoperative opioids (13). In accordance to above findings, our previous study identified five very similar risk factors: 1) female, 2) history of previous PONV or motion sickness, 3) duration of anesthesia more than 1 hr, 4) non-smoking status, and 5) use of opioid in the form of patient controlled analgesia (PCA), in the order of relevance (7).

The etiologies of PONV have been identified to be multi-factorial with the involvement of numerous receptor systems, and there has been growing interests in using a combination of antiemetics from different classes for PONV prophylaxis (2, 9, 14). Many studies have already proven that antiemetic interventions are effective in the prevention of PONV, and furthermore, selective PONV prophylaxis in patients at high risk for PONV is more cost-effective and associated with a higher degree of patient satisfaction compared with treatment of established symptoms (2, 15). Tramer (2) has concluded in his review of strategies for PONV that there is still no 'gold standard' antiemetic regimen for complete eradication of PONV but has proposed a rational three steps approach to minimize PONV: identification of patients at risk, keeping the baseline risk low, and multimodal anti-emesis for patients who are identified as high risk patients. In addition, a multidisciplinary panel of experts produced consensus guidelines for managing PONV and developed algorithm for most appropriate prophylaxis of PONV where surgical patients are categorized into three classes (low, moderate, and high) based on the patients' risk factors (16). Similar to this algorithm, we have arbitrarily classified patients into four groups from our previous study based on the incidences of PONV: low or mild (<20%), moderate (20-40%), high (40-60%), and very high (>60%).

In this study, we have selectively administered a combination of ondansetron and dexamethosone in high-risk and very high-risk groups, and the incidences of PONV in these respective groups were decreased by 29.1% and 27.9%. In addition, both high-risk and very high-risk groups showed a similar degree of decreases in the relative risk, 59.0% vs. 53.8%. These results are similar to the Apfel's (1) study in which they have reported that the risk of PONV was reduced by about 26% each for ondansetron and dexamethasone and the combination of these two drugs yielded greater than 50% reduction. However, based on the results of our study, more relevant PONV management, supplementary to prophylaxis, might be warranted in very high-risk patients where PONV was still evident in approximately 30% despite the prophylaxis. More recently, a multimodal management strategy for the prevention of PONV has been studies extensively and reported to be very effective (14, 16, 17). Habib et al. (18) demonstrated that a multimodal PONV prophylaxis regimen incorporating total IV anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol and a combination of ondansetron and droperidol is more effective than a combination of these antiemetics in the presence of an inhaled anesthetic. Their multimodal management strategy was associated with a higher complete response rate (no PONV and no rescue antiemetic) and greater patient satisfaction. Therefore, in addition to the combination of antiemetics acting at different receptor sites, the multifactorial etiology of PONV might be better addressed by adopting a multimodal approach, especially in patients with very high-risk factors for PONV.

The limitation of this study was that we selected the patients from our previous study as the control group rather than using a placebo control group because these patients had comparable risk factors of PONV and matching characteristics with the patients in the treatment group. Furthermore, it was considered unethical to select the control group and leave them unattended about the high risk of PONV. In addition, same investigators following the same method performed both studies.

In conclusion, the prophylactic administration of dexamethasone and ondansetron reduced the incidence of PONV in patients at both high-risk and very high-risk by 50%. However, very high-risk patients still showed an around 30% incidence of PONV despite the prophylactic administration of antiemetics. In this regard, future studies should be directed on the multimodal approaches covering from prophylactic antiemetics to TIVA to reduce the incidence of PONV in very high-risk patients.

References

- 1.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, Zernak C, Danner K, Jokela R, Pocock SJ, Trenkler S, Kredel M, Biedler A, Sessler DI, Roewer N. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tramer MR. Strategies for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2004;18:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watcha MF. The cost-effective management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:931–933. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biedler A, Wermelt J, Kunitz O, Muller A, Wilhelm W, Dethling J, Apfel CC. A risk adapted approach reduces the overall institutional incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:13–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03018540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koivuranta M, Laara E, Snare L, Alahuhta S. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.117-az0113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi DH, Ko JS, Ahn HJ, Kim JA. A korean predictive model for postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:811–815. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.5.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domino KB, Anderson EA, Polissar NL, Posner KL. Comparative efficacy and safety of ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199906000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill RP, Lubarsky DA, Phillips-Bute B, Fortney JT, Creed MR, Glass PS, Gan TJ. Cost-effectiveness of prophylactic antiemetic therapy with ondansetron, droperidol, or placebo. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:958–967. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200004000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhart LH, Morin AM, Bothner U, Georgieff M. Droperidol and 5-HT3-receptor antagonists, alone or in combination, for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:1252–1257. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.441011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henzi I, Walder B, Tramer MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:186–194. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Food and drug administration black box warning on the perioperative use of droperidol: a review of the cases. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1377–1379. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000063923.87560.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gan TJ. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1884–1898. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219597.16143.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Combination therapy for postoperative nausea and vomiting - a more effective prophylaxis? Ambul Surg. 2001;9:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6532(01)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White PF, Watcha MF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: prophylaxis versus treatment. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, Kovac A, Philip BK, Sessler DI, Temo J, Tramer MR, Watcha M. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apfel CC, Kranke P, Eberhart LH, Roos A, Roewer N. Comparison of predictive models for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:234–240. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habib AS, White WD, Eubanks S, Pappas TN, Gan TJ. A randomized comparison of a multimodal management strategy versus combination antiemetics for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:77–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000120161.30788.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]