Abstract

Only a few reports have focused on ocular motor paralysis in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. We report a case of ocular motor paralysis resulting from herpes zoster. The patient, an 80-yr-old woman, presented with grouped vesicles, papules, and crusting in the left temporal area and scalp, with diplopia, impaired gaze, and severe pain. Her cerebrospinal fluid analysis was positive for varicellar zoster virus IgM. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed to rule out other diseases causing diplopia; there were no specific findings other than old infarctions in the pons and basal ganglia. Therefore, she was diagnosed of abducens nerve palsy caused by herpes zoster ophthalmicus. After 5 days of systemic antiviral therapy, the skin lesions improved markedly, and the paralysis was cleared 7 weeks later without extra treatment.

Keywords: Abducens Nerve, Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

INTRODUCTION

Herpes zoster is a localized disease characterized by unilateral radicular pain and a vesicular eruption caused by the varicella zoster virus. In addition to sensory neurons, it may also affect motor neurons in rare cases. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus has caused extraocular muscle palsies of the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves in 7 to 31% of patients (1-3). The third nerve appears to be the most commonly affected, and the fourth nerve, the least. In herpes zoster ophthalmicus, extraocular muscle palsies usually appear 2 to 4 weeks after a rash, but sometimes occurs simultaneously with a rash or more than 4 weeks later. The extraocular muscle palsies associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a transient, self-limited condition, usually seen in the elderly (4, 5). Such cases have not often been reported, although extraocular muscle palsies caused by herpes zoster ophthalmicus appears frequently.

CASE REPORT

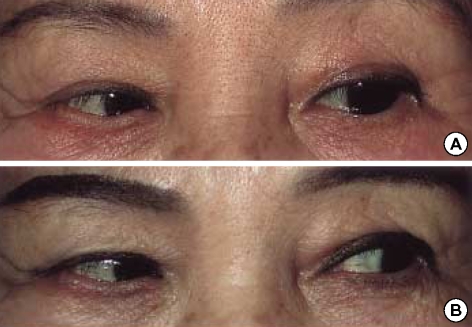

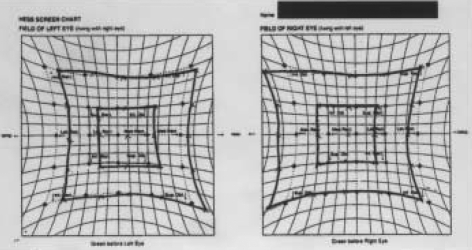

An 80-yr-old female had been in good health until she developed sharp, lancinating pain over the left side of the scalp. Four days later, a vesicular eruption occurred in the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve on the left side of the scalp, and this was accompanied by diplopia (Fig. 1). On ophthalmologic consultation, diplopia was present in the primary position and was more pronounced on attempted abduction of the left eye (Fig. 2A). A Hess chart shows the ocular movements of left VI nerve palsy in this case (Fig. 3). The remainder of the physical examination was within normal limits. Blood tests were normal, including liver and renal function tests, whereas the white blood cells (WBCs) were increased at 11,500 per mL, with 82.4% being segmented neutrophils. The patient suffered from fever and headache, and thus the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was examined to rule out herpes zoster encephalomeningitis, which revealed that varicella zoster virus IgG and IgM were elevated. However, other CSF findings such as WBC counts, proportions of lymphocytes, and the protein level were within normal limits. There were no specific findings on the neurological examination. Brain magnetic resonance imaging was normal except for old infarctions in both basal ganglia and the periventricular white matter. The good general health and negative neurologic and laboratory examinations in our patient excluded other causes of acquired paresis of the nerve, such as vascular cerebral accidents, brain tumors, and encephalitis. A diagnosis of herpes zoster was made, and acyclovir 800 mg was given intravenously for 5 days. Despite our advice to continue therapy, the patient wanted to discharge after 5 days. So further treatment was stopped. The skin lesions resolved within 1 week, although the diplopia was still present. On follow-up examination 7 weeks later, the abducens nerve palsy had improved without extra treatment (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Erythematous papules with crusts and erosions on the left scalp and left ear lobe.

Fig. 2.

(A) Unsuccessful abduction of the left eye during attempted left gaze. (B) Without extra treatment, slow improvement of the left lateral rectus palsy was observed 7 weeks later.

Fig. 3.

Hess screen test: paresis of the left lateral rectus with overreaction of the right medial rectus indicates the ocular movements in left sixth nerve palsy.

DISCUSSION

Sixth nerve palsy is the most common cranial nerve palsy affecting the ocular motility. Patients present with horizontal diplopia, which is worse on looking to the affected side, and often the face turns to the affected side.

The third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves control eye movements. The third nerve, which controls internal, inferolateral, superolateral, and superomedial eye movements, is infected most commonly with herpes zoster, whereas abducens palsy complicating herpes zoster is relatively uncommon (6-8).

The mechanism through which the ocular motor nerves or muscles are involved in zoster is not clear. Denny-Brown et al. (9) found that motor neuritis was independent of the inflammation of any ganglion. Edgerton (2) and Godtfredsen (10) postulated that the involvement of the second, third, fourth, and sixth nerves was attributable to contiguous intracavernous radiculomeningitis. While contiguous intracavernous spread is a distinct possibility, Sunderland and Hughes (11) concluded that there was no communication between the fifth nerve and the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, although sympathetic branches temporarily attached to the abducens nerve as they passed from the carotid plexus to the ophthalmic and maxillary nerves. Kreibig (12) postulated that the extraocular palsies were due to perivasculitis-myositis, rather than to a neural origin. Muscle ischemia remains a strong possibility, as does a combination of orbital nerve and muscle inflammation. Therefore, isolated abducens nerve palsy might be caused by circumscribed orbital myositis or a lymphocytic cranial motor neuropathy.

Multiple mechanisms have been documented in the cases examined histopathologically, and the histology of the lesion within one patient may have a variety of forms in different locations (13). It is probable that all of these mechanisms of disease, working separately or simultaneously, are responsible for the clinical presentation (14).

There are different suggestions about the treatment of the paralytic lesions that complicate herpes zoster. Some authors have examined the effectiveness of antiviral therapy and adrenal cortex hormones. As the paralytic lesions tend to resolve spontaneously, the effects of specific treatment are unclear (15, 17). In our case, the paralytic lesion resolved completely within 7 weeks without specific treatment. The recovery time was similar to that in the previous report, the 6 and 8 weeks respectively (7, 8). The prognosis for spontaneous recovery of extraocular muscle function has been reported to be favorvable (4, 16).

References

- 1.Hunt JR. The paralytic complications of herpes zoster of the cephalic extremity. JAMA. 1909;53:1456–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edgerton AE. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: report of cases and review of literature. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1942;40:390–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly V, Dulley B. Ocular motor defects associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. In: Moore S, Mein J, Stockbridge L, editors. Orthopotics-Past, Present and Future. Symposium Specialist. New York: Stratton Intercontinental Medical Book Corp; 1976. pp. 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser JS. Infranuclear disorders of eye movement. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology. Vol 2. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott; 1994. pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang-Godinich A, Lee AG, Brazis PW, Liesegang TJ, Jones DB. Complete ophthalmoplegia after zoster ophthalmicus. J Neuroophthalmol. 1997;17:262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta D, Vishwakarma SK. Superior orbital fissure syndrome in trigemino-facial zoster. J Laryngol Otol. 1987;101:975–977. doi: 10.1017/s002221510010310x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bak CG, Jun DC, Kim JH, Kim HT, Kim SH, Kim MH. A case of ophthalmoplegia caused by herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2002;20:295–297. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jude E, Chakraborty A. Images in clinical medicine, left sixth cranial nerve palsy with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:e14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm040899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denny-Brown D, Adams RD, Fitzgerald PJ. Pathologic features of herpes zoster: a note on "genicular herpes". Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1944;51:216–231. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godtfredsen E. Pathogenesis of cranial nerve lesions, notably ophthalmoplegias, complicating herpes zoster opthalmicus. Acta Psychiatr Neurol. 1948;23:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1948.tb09356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunderland S, Hughes ESR. The pupilloconstrictor pathway and the nerves to the ocular muscles in man. Brain. 1946;69:301–309. doi: 10.1093/brain/69.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreibig W. Die Zosterekrankung des Auges. Klin Monatsbl Augenheikd. 1959;135:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobo LM, Foulks GN, Liesegang T, Lass J, Sutphin JE, Wilhelmus K, Jones DB, Chapman S, Segreti AC, King DH. Oral acyclovir in the therapy of acute herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Opthalmology. 1985;92:1574–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33842-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh RJ, Dulley B, Kelly V. External ocular motor palsies in opthalmic zoster: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:677–682. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.11.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenlaub P, Grange F, Nasica X, Guillaume JC. Oculomotor nerve paralysis with complete ptosis in herpes zoster ophthamicus: 2 case. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1997;124:401–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karbassi M, Raiaman MB, Schuman JS. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;36:395–410. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross G, Schofer H, Wassilew S, Friese K, Timm A, Guthoff R, Pau HW, Malin JP, Wutzler P, Doerr HW. Herpes zoster guideline of the German Dermatology Society (DDG) J Clin Virol. 2003;26:277–289. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]