Abstract

Channels and cavities play important roles in macromolecular functions, serving as access/exit routes for substrates/products, cofactor and drug binding, catalytic sites, and ligand/protein. In addition, channels formed by transmembrane proteins serve as transporters and ion channels. MolAxis is a new sensitive and fast tool for the identification and classification of channels and cavities of various sizes and shapes in macromolecules. MolAxis constructs corridors, which are pathways that represent probable routes taken by small molecules passing through channels. The outer medial axis of the molecule is the collection of points that have more than one closest atom. It is composed of two-dimensional surface patches and can be seen as a skeleton of the complement of the molecule. We have implemented in MolAxis a novel algorithm that uses state-of-the-art computational geometry techniques to approximate and scan a useful subset of the outer medial axis, thereby reducing the dimension of the problem and consequently rendering the algorithm extremely efficient. MolAxis is designed to identify channels that connect buried cavities to the outside of macromolecules and to identify transmembrane channels in proteins. We apply MolAxis to enzyme cavities and transmembrane proteins. We further utilize MolAxis to monitor channel dimensions along Molecular Dynamics trajectories of a human Cytochrome P450. MolAxis constructs high quality corridors for snapshots at picosecond time-scale intervals substantiating the gating mechanism in the 2e substrate access channel. We compare our results with previous tools in terms of accuracy, performance and underlying theoretical guarantees of finding the desired pathways. MolAxis is available on line as a web-server and as a standalone easy-to-use program (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/MolAxis/).

Keywords: Molecular Dynamics MD, Cytochome P450 3A4 CYP3A4, Large pore channels LPC, Adenosine triphosphate binding cassette ABC, Transmembrane TM, Medial axis

Introduction

Cavities, channels, pockets, and surface grooves in proteins are potential sites for binding and interaction with drugs, ligands, nucleic acids and proteins. The interaction defines the protein function. Consequently, a large number of computational methods and algorithms have been developed to detect and characterize protein functional sites.1–7 Most approaches typically point to the largest cavity or pocket as the binding or active site. In many cases, especially in enzymes including the ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase,8 haloalkane-dehalogenase,9 neurolysin,10 the Cytochrome P450 family11, acetylcholinesterase12 and many more, the active site which is the largest cavity is found in the buried core of the protein. In order for the reaction to occur, the substrate or ligand must access the active site from the protein exterior. Yet, these tools do not find or predict the way to reach the pocket from the surface of the protein. Substrate specificity is influenced not only by interactions at the binding site but also by the selectivity of access routes to the binding site which is determined by the size, shape and physico-chemical properties of those routes. The question of substrate selectivity is of major importance in biochemistry and medicinal chemistry, for understanding catalytic mechanisms, and in drug design.

Void and cavity finding algorithms are limited in their ability to detect the channel of transmembrane (TM) proteins. Many drug targets such as ion channels13,14, transporters15, and receptors16 include transmembrane channels and determining their inner surface is expected to assist in developing more selective drugs with less side effects. The program HOLE17 analyzes and displays the pore dimensions of ion channels and is suitable mainly for close-to-straight channels. However, for a channel with greater curvature and for finding channels emanating from cavities HOLE is rather limited. A new tool called CAVER18 was developed to explore routes from protein clefts and cavities. Its underlying algorithm is based on a skeleton search using a three-dimensional (3D) grid. Given a starting point, the program identifies and visualizes pathways from the inside of the protein to the bulk solvent. The protein is mapped onto a 3D grid and each grid cell is weighted such that the lowest weighted cells are surrounded by empty space. The search algorithm detects all the lowest weighted cells and finds the lowest cost paths from the starting point to the surface of the protein. An improved tool, called MOLE19, was also recently developed by the same group. It replaces the numerous grid vertices of CAVER by a smaller number of vertices, which are located on the Voronoi diagram of the centers of the atoms. This leads to an efficient algorithm, with results similar to the ones obtained by CAVER.

Tools from the field of computational geometry are often used in structural biology. In particular, computational-geometry techniques and paradigms were developed which help in representing and analyzing molecular structures. The alpha shapes theory20 is used to describe the topological and geometrical features of molecules, such as measuring the surface area and volume of pockets.21 However, the alpha complex of a molecule is not sufficient to describe features of channels such as its skeleton or diameter. We rely on alpha shapes and another geometrical concept: the medial axis. The medial axis of a general surface is the collection of three-dimensional points that have more than one closest point on the surface. For example, the medial axis of the surface of a cylinder is simply the axis of the cylinder. The medial axis has applications in motion planning, reverse engineering, feature extraction, mesh generation and more.22 Here, the surface at hand is the van der Waals (VDW) surface of a molecule. It divides up neatly into an inner medial axis and outer medial axis, i.e. the points of the medial axis that are inside the molecule and the points that are outside the molecule (the complement of the molecule). The inner medial axis of a molecule can be seen as the skeleton of the molecule and it is composed of parts of planes or flat facets. On the other hand, the outer medial axis of a molecule is the collection of points outside the molecule that have more than one closest atom and is composed of hyperbolic patches, which makes it hard to compute in an exact manner.

We represent molecular channels using corridors. A corridor is a probable route taken by a small molecule passing through a channel. To give a picturesque metaphor, imagine a volcano erupting at a given point which lies outside the molecule volume (for example, located inside a molecular chamber). The lava is flowing out of the volcano mouth in a set of streams that flow faster where the passage is wide and slower where the passage is narrow. Whenever a stream reaches an obstacle (like the molecule VDW surface or another stream) that cannot be bypassed it stops flowing. Streams tend to balance between length and clearance and they represent corridors in this analogy. Corridors are well defined geometrical entities which we define below in the Theory and Algorithm Section.

MolAxis is a new tool that allows fast identification of corridors in the complement of the molecule. MolAxis employs a novel algorithm23 based on alpha shapes in order to approximate a useful subset of the medial axis of the complement of the molecule. To the best of our knowledge it is the first attempt to approximate and analyze the medial axis of the complement of molecules in order to construct channels. The most notable advantage of our approach is that the medial axis is composed of twodimensional surface patches, i.e., we convert a three-dimensional problem to a two dimensional problem, which improves dramatically the performance of the algorithm. MolAxis can automatically compute a source point in the center of the main void with a high success rate or allow a user-specified source point.

In this paper, we apply MolAxis to four static protein structures: the Large Pore Channels (LPC), a bacterial membrane protein; an ABC transporter protein; a bacterial cytochrome P450 (P450); and a human P450. Application to the ABC transporter protein has shown that the medial axis shape is smooth, reflecting the pathway generated by small molecule movements as it passes through the channel. In the P450 case study, we identify and characterize pathways emanating from a source point in the main cavity of a protein to its surface hundred times faster than CAVER. For example, in a grid resolution of 0.4Å, CAVER finds most previously determined channels11 within the first ten identified pathways in about 64 hours whereas MolAxis finds more channels with a similar resolution in less than two seconds (see Table 1). The MOLE software improved the running times as compared to CAVER and they were similar to MolAxis. Furthermore, in the human P450 3A4 we detected almost all known channels within the first ten identified pathways, some of which are nearly closed, consequently undetected by CAVER and MOLE. For example, CAVER and MOLE did not detect the substrate access/exit channels 2c, 2f and 3 and the water channel W previously described11 within the first ten identified pathways. After running CAVER and MOLE in the search for more channels, still not all known channels were detected. MolAxis typically found unique geometric pathways, namely, every channel was reported exactly once and there was no need for clustering as in the case of MOLE.

Table 1.

The number of times each CYPcam substrate- or water- channel type was identified at different resolutions using four types of running modes: User/Auto/Cavera and Moleb (last row)

| Channel typesc | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Res.(Å)d | running timese | 1 | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2e | 2f | 3 | S | W | other |

| 0.1 | 6.97s/19.31s/NA | 1/2/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/0 | 2/0/0 |

| 0.2 | 3.95s/9.58s/NA | 2/2/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 | 0/1/0 |

| 0.3 | 1.77s/3.77s/NA | 2/2/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.4 | 1.67s/3.62s/64h | 2/2/2 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.5 | 1.71s/3.68s/15h | 2/2/4 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 0/0/1 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.6 | 1.70s/3.70s/6h | 2/2/2 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 0/0/2 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.7 | 1.74s/3.78s/1.5h | 2/2/3 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 0/0/1 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.8 | 1.66s/3.66s/57m | 2/2/5 | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/1 | 0/0/1 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 |

| Moleb | 10s | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The first 10 identified channels are indicated.

In User mode the user supplies the starting point for MolAxis. In Auto mode, MolAxis identifies the center of the largest cavity and sets it as the source point. In Caver mode the runs were performed with CAVER initiating at a user specified point.

In Mole mode the runs were performed with MOLE initiating at the same user specified point as in MolAxis.

Channels are denoted following Cojocaru et al 11. classification. Channels 1, 2a, 2b, 2c, 2e, 2f, 3 are substrate channels; S is a solvent channel and can be substrate channel; W stands for a water channel.

The left column specifies the resolution. The resolution for CAVER is the grid cell size.

The resolution for MolAxis is defined in the Theory and Algorithm Section.

NA - Not applicable; s – seconds; m – minutes; h – hours.

In addition we apply MolAxis to a series of snapshots generated by a 6 ns explicit water Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation of the human P450 3A4 substantiating the gating mechanism in the 2e substrate access channel. MolAxis can be applied to huge datasets such as snapshots derived from long MD trajectories to obtain pathways that represent probable routes taken by small molecules passing through channels.

Theory and Algorithm

We model a molecule using a collection of three-dimensional balls, one ball per atom and assign each ball its corresponding VDW radius. The outer medial axis of a molecule can be seen as a skeleton of the complement of the molecule. It is a natural starting point to look for pathways since it tends to be distant from the surface of the molecule, yet it has the same shape as the complement of the molecule (the technical term is ‘homotopy equivalent’), as was recently shown for a general family of shapes.24 Computing the outer medial axis of a molecule can be done in an exact manner.25 We applied an approximation scheme for two main reasons: simplicity of implementation and efficiency of computation. As the molecular model is approximate to begin with, the incurred inaccuracy is negligible.

In our approximation scheme we first scale the atoms such that the smallest atom is a unit ball. We then replace each atom with a collection unit balls that we call the approximating balls of the atom. The switch from varying-radius balls to same-radius balls entails the construction of much simpler objects: Instead of dealing with curved algebraic surfaces we only have to deal with polygons in space. Moreover, the Pathway diagram that we compute is contained in the standard Voronoi diagram of the centers of the approximating balls, which in turn is a very-well studied structure for which robust and efficient implementations exit. We call the collection of all approximating balls the approximate molecule. The VDW surface is the boundary surface of the molecule. The approximate VDW surface is the boundary surface of the approximate molecule. The user supplies a resolution parameter ε and MolAxis guarantees that every point of the VDW surface has a corresponding point in the approximate VDW surface such that the distance between the two points is at most ε. The number of unit balls needed to approximate a molecule depends mainly on the ratio between the largest and the smallest atom. Elsewhere23 we describe our approximation method in detail and give a bound on the number of approximating balls needed by our algorithm to guarantee the desired approximation quality ε. We call the portion of the Voronoi diagram of the centers of the approximating balls that does not intersect the approximated molecule the pathway diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An example of a collection of same-size circles (light blue) approximating varying-size circles, and the pathway diagram of their centers. The discarded portion of the Voronoi diagram of their centers is depicted using dotted lines.

A pathway π is a curve in space that lies outside the approximate molecule and is contained in the pathway diagram. Let π be a pathway and p be a point on it. The clearance c( p) of p is the minimal distance between p and the approximate VDW surface. The lining balls of p are the collection of (one or more) approximate ball(s) with a minimal distance to p. We call an atom A a lining atom of p if at least one of the lining ball(s) of p approximates A. A lining residue of p is a residue that contain one or more lining atoms of p.

The profile of π is the clearance of the points on π as a function of the distance along the pathway. The pathway ball of p in π is the ball with radius c(p) that is centered at p. The pathway surface of π is the boundary (envelope) surface of the union of all pathway balls of π. The bottleneck radius of π is the minimal clearance along the pathway, and the bottleneck point of π is the point in π where the bottleneck radius is achieved. The bottleneck atoms (resp. bottleneck residues) are the lining atoms (resp. lining residues) of the bottleneck point.

The exact clearance c̅(p) of a point p in the complement of the molecule is the distance between p and the (exact) VDW surface. We state here a lemma proved elsewhere:23

Lemma 1 For any p in the pathway diagram such that c(p) > ε it holds that |c(p)–c̅(p)|≤ ε.

This lemma justifies our use of the clearance function as an approximation of the idealistic exact clearance function.

Pathway Graph Construction

The pathway diagram is composed of two-dimensional patches (see Figure 1). In order to reduce the problem to a one-dimensional problem we create a graph, which contains only vertices and edges. First, we discard all facets of the pathway diagram. Due to geometric properties of the Voronoi diagram of points, one of the edges of a bounded facet F always has higher clearance than the inside of the facet F. Thus discarding facets favors pathway clearance (at the possible expense of increasing the pathway length). A more robust approach could have been to sample vertices within the facet, yet we did not find this improvement necessary. Second, some edges of the pathway diagram are rays, going to infinity. We replace the rays with segments by intersecting the pathway diagram with a bounding sphere, as we describe next.

Let Q be a large user-specified bounding sphere. For each Voronoi edge e = (vi,vo) that intersects Q, with vi inside Q and vo outside Q, we construct a new vertex ve that is the intersection of e and Q. We call ve a boundary vertex. We also construct a boundary edge e’ = (vi,ve), which is the part of e that lies within Q. We define V to be the collection of Voronoi vertices of the pathway diagram that lie within Q along with all the boundary vertices. In a similar fashion, we define E to be the collection of Voronoi edges of the pathway diagram that lie completely within Q along with all the boundary edges. We construct a graph G = G(V,E) which we call the pathway graph. From this point on we restrict ourselves to pathways that are contained in the pathway graph.

Corridor Tree Construction

Pathways are not unique and more than one pathway can exist between two points. There are several ways to define an optimal pathway between two points. One way is the shortest pathway between the two points. Another way is to focus only on the clearance of the pathway. The shortest pathway between two given points typically has the undesirable property that it can be arbitrarily close to the boundary of the molecule and hence has close to zero bottleneck radius. High clearance pathways, on the other hand can be extremely long. We are therefore interested in finding pathways that balance between length and clearance.

For any vertex v ∈ V located at p ∈ R3 we define its clearance to be c(v) = c(p). For each edge e(v, v’)∈E, the edge clearance c(e) is defined in Equation 1:

| (1) |

where Cmax is a user-defined constant, which serves as an upper bound on the clearance. We define a weight function w(e) over the edges that accounts for the length of the edge and the clearance of points along the edge in Equation 2:

| (2) |

where d(v,v’) is the Euclidean distance between v and v’. We employ a minimum weight optimization algorithm on the graph G and compute a tree. The weight function w(e) favors pathways that are both short and wide and can be seen as a flux optimization. The weight function can be easily modified and adapted to optimize other criteria. We select a root vertex s in a manner described below and compute the tree rooted at s using Dijkstra’s algorithm26 on G with the weights defined by w(e). We call this tree the corridor tree of the molecule.

During the computation of the tree each vertex v is assigned a flux weight W(v), which is the sum of the weights of the edges on the path between s and v. We say that u∈V is an ancestor of v ∈ V if it is contained in the (single) path from the root vertex s to v in the corridor tree. A vertex v ∈ V is called a leaf vertex if it is a leaf in the corridor tree, i.e., v is not an ancestor of any vertex in V. A corridor π is a path in the corridor tree that reaches a leaf vertex vπ. We define the flux weight of a corridor π to be the flux weight W(vπ) of its leaf vertex vπ.

Querying the Corridor Tree

The corridor tree construction is done as a preprocess, and it is saved to a file. We support various queries to allow the user to identify, display and analyze a single corridor in the corridor tree. The user can query the corridor tree in order to identify the corridor π that has the smallest flux weight and that passes through a user-specified sphere. MolAxis gives as output the corridor profile, lining atoms, lining residues, bottleneck radius, bottleneck atoms and bottleneck residues. For visualization purposes, MolAxis constructs the corridor surface of channels either as a collection of balls or as a meshed surface (see results section).

MolAxis supports special queries designed for two scenarios, namely chamber channels (e.g. the P450 Enzyme) and cross channels (transmemrane channels). Chamber channels are channels that connect an inner chamber to the outside. MolAxis identifies chamber channels by reporting on corridors that connect the root vertex (placed inside the chamber) to boundary vertices as described below. A cross channel is a channel that crosses the protein from side to side, like a transmembrane channel. In this case MolAxis gives as a result a concatenation of two corridors that together represent the channel as described below.

Chamber Channels

In the first scenario, dealing with chamber channels, we select the root vertex s to be one of the vertices within the chamber. This is done either by selecting a vertex closest to a user-specified point or by automatically computing the center of the largest chamber in the protein. The latter option is called Auto mode. The largest chamber is deduced using persistent topology techniques similar to the one used by Edelsbrunner et al.27. It is the vertex in the center of the last remaining void if the approximated balls are inflated in a uniform manner. We distinguish between two types of chamber corridors. Corridors that reach a boundary vertex are called exit corridors since they exit the chamber, while all other corridors are called dead-end corridors. We use exit corridors to represent the molecular channels.

We define the forking vertex v(π1,π2) of two corridors π1,π2 to be the last identical vertex in the path from s to the leaf vertices of π1 and π2 (the forking vertex is also known as the least common ancestor of the leaf vertices of π1 and π2). The vertex v( π1,π2) might be located far outside the chamber or even outside the convex hull of the molecule, which means that the two corridors actually represent the same channel. In this case one of the corridors should be discarded. We introduce a user-specified parameter Fmax called the forking threshold to control when corridors are discarded as described below. We define the distance d(v) of a vertex v to be the sum of the length of the edges that connect the root vertex to v in the corridor tree.

First we color all vertices in V blue. We traverse all exit corridors in a sequence π1,π 2,…, sorted in ascending order of their flux weight, i.e., starting from the exit corridor that has the best (lowest) flux weight. Let πi be an exit corridor in the sequence. The forking distance of πi for i > 1 is the minimal distance of all forking vertices with respect to previous corridors in the sequence: . We set f(πi) to be the distance of the last red vertex in πi (in the first iteration no vertex is colored red, so we trivially set f(π1) = 0). We report to the user the corridor πi only if its forking distance is smaller than the forking threshold Fmax. If the forking distance of πi is not smaller than the forking threshold, we regard πi as similar to a previously reported exit corridor and therefore discard it. We then color the vertices of πi red, and continue to the next exit corridor in the sequence (see Discussion section).

Cross Channels

In this scenario our primary purpose is to identify transmembrane (TM) channels. We add an imaginary vertex v∞ at infinity, connect it with edges to all the boundary vertices and set the weight of these new edges to zero. We set the root s to be v∞ and compute the corridor tree. The user must specify a cross plane, which is a plane that splits the boundary vertices into two groups: above vertices and below vertices. Given an edge e = e(v1,v2)∈E that is not in the corridor tree, we call e a crossing edge if the ancestor boundary vertex u1 of v1 is an above vertex and the ancestor boundary vertex u2 of v2 is a below vertex. In this case, we define the crossing corridor πe to be the concatenation of the corridor leading from u1 down to v1 in the corridor tree, the edge e and the corridor leading from v2 up to u2 in the corridor tree. There might be crossing corridors that bypass the transmembrane channel. Therefore we discard crossing corridors that do not pass through a user-specified sphere. If no crossing corridors are left we report that the channel is closed. If there is more than one candidate for a crossing corridor we report the crossing corridor with the smallest flux weight.

Results

All tests were carried out on a Pentium IV 3.0 GHz machine with 1GB of RAM running a LINUX native operating system. We ran MolAxis, CAVER, MOLE and HOLE with the same atom VDW radii. In all runs the user-defined constant Cmax was set to 1.4Å, the convention for the radius of water molecules.

The CGAL28 open source project is aimed at making the large body of theoretical algorithms and data structures applicable, while focusing on reliability and performance. We implemented the MolAxis program using the CGAL library which resulted in good performance and robustness. MolAxis output can be visualized and manipulated by the VMD29 software. The channel figures presented in the sequel were created using VMD (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd).

Transmembrane (TM) proteins

TM proteins are structurally divided into three subtypes: a) globular proteins that are anchored to the membrane by a single alpha helix; b) proteins that contain several TM α helices and c) β structural membrane proteins. We used MolAxis to compute profiles and bottleneck residues of TM channels. In the case of TM channels the bottleneck residues are considered to be the residues forming the channel gate. We ran MolAxis on a β membrane protein and on an α helical protein and compared the outputs to those of the program HOLE.

A. Large pore channels

Large pore channels (LPC) are membrane proteins located in the outer membrane of the bacteria through which the supply of molecules (such as sugars) flow to the cytoplasm. The LPC structure (PDB code 1PRN) consists of a β-barrel that forms a straight channel. The channel narrows in the middle and has wide open conformations at both its ends (see Figure 2a). The narrowing contributes to selective passage of molecules and determines ions conductivity.30 As can be seen from Figure 2, HOLE and MolAxis agree on the results and both find an almost identical path with a similar running time of about 5 seconds. The radius at the narrowest point is 3.9Å and the corresponding residues are Y96 and the negatively-charged D90 on one side and the positively charged R32 on the opposite side. The program MOLE found the main channel as well.

Figure 2.

a) LPC channel surface as calculated by MolAxis (blue) and HOLE (red). The LPC is shown in ribbon. b) LPC pore radius along the Z axis as calculated by MolAxis (blue) and HOLE (red).

B. ABC transporter

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette (ABC) transporters catalyze the translocation of substrates against a concentration gradient by coupling it to ATP hydrolysis.31 ABC transporters (PDB code 2NQ2) consist of four domains, two α-helical TM domains (upper part of Figure 3a) and two nucleotide binding domains (NBD) placed in the cytoplasm (lower part of Figure 3a). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, a sub-group of these transporters is involved in the efflux of hydrophobic drugs causing anti-microbial and chemotherapeutic multi-drug resistance (MDR).32 The conformational changes upon substrate exit are not well understood. At least the polar parts of the substrate may orient to exit through the chamber between the TM and NBD domains.32 In general both HOLE and MolAxis have similar outputs: the inner chamber is connected to the TM channel leading outside the cell. There is a narrowing of the channel above the chamber from 7Å to 4Å (see Figure 3c) with polar residues R88 and N89 forming the chamber roof. Then, the channel opens to a radius of 5.5Å (local maximum) and finally it closes near the end of the TM region. Although HOLE and MolAxis calculate similar pore radius profiles, the axes of the channel are quite different (Figures 3b and 3c). As can be seen in Figure 3b, the path found by HOLE (in red) has a ‘zigzagging’ pattern while MolAxis (in blue) detects a smoother path of the channel which is a more reasonable movement of an exiting drug and better represents the channel geometry (see Discussion). It should be noted that MOLE found the main channel along with other non-relevant channels.

Figure 3.

a) The ABC transporter channel surface as calculated by MolAxis (blue) and HOLE (red). The ABC transporter is represented by ribbon. b) A closer look of figure (a) the surface and medial lines of the channel obtained by MolAxis (blue) and HOLE (red). c) ABC transporter pore radius along the Z axis as calculated by MolAxis (blue) and HOLE (red). The Z axis is directed from the cytoplasm to the cell exterior.

Enzymes cavities (the Cytochrome P450 family)

Cytochrome P450 (P450) proteins constitute a large family of mono-oxygenases heme containing enzymes that oxidize a variety of chemical compounds in microorganisms, plants and mammals.33,34 The oxidation of a substrate occurs at the hydrophobic core of the protein via a catalytic cycle which is thought to be common to all heme monooxygenases including P450s.35 The active site is buried inside the protein to prevent uncoupling between electron donation and mono-oxygenation thereby rendering the enzyme non-productive.36 Differences in substrate access and product egress routes may determine substrate specificity profiles.37 Therefore, it is of great mechanistic and biochemical interest to identify and characterize all channels that link the active site to bulk solvent both statically and dynamically by means of MD simulations. We ran MolAxis and compared our results to CAVER and MOLE on two P450s: a) a bacterial P450 that oxidizes the substrate camphor (CYPcam)38 and b) the human Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4)39–41 enzyme that is responsible for the oxidation of nearly 50% of all drugs taken orally.42 Channel classification is based on the secondary structure elements forming the mouth of the channel following the Cojocaru and coworkers nomenclature11 (see Figure 4, Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). Substrate channel 1 egresses between the C and H helices; substrate channels 2a egress in the vicinity of the FG loop, 2b between the G helix BC loop and β1 sheet, 2c between the G helix and BC loop (opposite to 2b channel in relation to the BC loop), 2e through the BC loop and 2f like the 2a channel but closer to the F helix. Substrate channel 3 extends between the F and G helices. The water channel (denoted W) passes between the heme and the N terminus of the BC loop. The solvent channel (denoted S) lies between the I and F helices. We were unable to detect such channels using the HOLE program and consequently HOLE was not used in these case studies.

Figure 4.

Surfaces of the CYPcam detected channels according to MolAxis (blue) and CAVER (red) in a 0.6Å resolution. CYPcam is represented by ribbons and the heme prosthetic group is represented as VDW and colored orange. Secondary structure elements such as the C helix, F helix, G helix, H helix, I helix and the BC loop are represented as ribbons and colored pink, purple, yellow, gray, black and green respectively.

Table 2.

The number of times each CYP3A4 substrate or water channel type was identified at different resolutions using four types of running modes: User/Auto/Cavera and Moleb (last row).

| Channel typesc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Res. (Å) d | running times e | 2a | 2b | 2c | 2e | 2f | 3 | S | W | Other |

| 0.1 | 8.29s/24.49s/NA | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/2/0 | 0/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/0/0 | 3/2/0 |

| 0.2 | 4.60s/12.30s/NA | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/0/0 | 2/2/0 |

| 0.3 | 2.02s/4.55s/11.30h | 1/1/0 | 1/1/6 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/4 | 1/2/0 | 2/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 0/1/0 | 2/1/0 |

| 0.4 | 1.96s/4.45s/2.06h | 1/1/0 | 1/1/6 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/4 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 |

| 0.5 | 1.99s/4.53s/35.00m | 1/1/1 | 1/1/6 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/3 | 2/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.6 | 1.96s/4.43s/14.00m | 1/1/2 | 1/1/5 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/3 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 |

| 0.7 | 1.94s/4.47s/6.00m | 1/1/0 | 1/1/5 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/3 | 2/1/0 | 2/1/0 | 1/1/2 | 0/1/0 | 1/1/0 |

| 0.8 | 1.97s/4.45s/3.00m | 1/1/3 | 1/1/5 | 1/1/0 | 1/2/2 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 1/1/0 | 2/1/0 |

| Moleb | 8s | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

In User mode the user supplies the MolAxis starting point. In Auto mode, MolAxis identifies the center of the largest cavity and sets it as the source point. In Caver mode the runs are performed with CAVER starting from a user specified point. The User and Caver runs are comparable. The first 10 identified channels are used.

In Mole mode the runs were performed with MOLE initiating at the same user specified point as in MolAxis. Mole’s first ten identified channels were clustered into four distinct channels.

Channels are denoted following Cojocaru et al11. Channels 2a, 2b, 2c, 2e, 2f, 3 are substrate channels, S is a solvent channel and can be a substrate channel, and W stands for a water channel.

The resolution for CAVER is the grid cell size. Resolution for MolAxis is defined in the Theory and Algorithm Section.

NA - Not applicable; s – seconds; m – minutes; h – hours. See also legend to Table 1.

Table 3.

Rank of the first 10 identified pathwaysa according to the flux weight of their corresponding corridor sorted in a descending orderb in CYP3A4 by the MolAxis, CAVER and Mole running modesc at 0.4Åd resolution.

| Channel rank | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run mode | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| User | 2e | 2b | 2c | 2a | 3 | S | 2f | other | W | other |

| Auto | 2e | 2b | 2a | 2c | 3 | 2e | 2f | S | other | W |

| Caver | 2e | 2b | 2b | 2e | 2b | 2b | 2e | 2b | 2b | 2e |

| Mole | 2e | 2b | 2b | 2b | 2a | 2a | 2b | 2a | 2b | S |

We match a corridor to a channel if it exits through the relevant secondary structure elements of the channel. We found that the correspondence between corridors and channels is high but it is not one-to-one. First, some channels had no corresponding corridors. This can happen when a channel is closed or when it is nearly closed and its exit mouth is close to a wider channel. We call the latter phenomenon overshadowing, since another channel is hiding the relevant channel; see more details in the Discussion Section below. Second, multiple corridors can match the same channel. We allow the user to address this problem by adjusting the forking threshold. A third possibility is corridors with no corresponding channels. This either signifies a possibly newly discovered channel or a random exit route that opens for a short time during an MD simulation.

A. Bacterial CYPcam

For the bacterial CYPcam (PDB code 1AKD) we compared three types of MolAxis configurations which were run with a range of resolutions. In CAVER the resolution is defined by the size of the grid cell whereas in MolAxis the resolution is defined as a bound on the maximal distance from the VDW surface to the approximate VDW surface, denoted ε. First we ran MolAxis in Auto mode, in which MolAxis identifies the center of the largest cavity and sets it as the source point. We also ran both MolAxis, CAVER and MOLE initiating with a user specified point which was placed on the C4 atom of the (omitted) camphor substrate. In all runs the forking threshold Fmax was set to 6. The MolAxis user-specified starting point runs, MolAxis Auto mode runs, CAVER and MOLE runs are denoted as User, Auto, Caver and Mole respectively (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). We compared the MolAxis User with Caver and Mole runs. The running times and channel types detected are summarized in Table 1. In general, we observe agreement between CAVER, MOLE and MolAxis channels found in CYPcam with the exception of the 2b channel that CAVER and MOLE do not detect at all in the first 10 identified pathways. This channel was detected by CAVER only after a long run of two hours at a grid resolution of 0.8Å and identification of 21 pathways. However, the running times are impressively faster with MolAxis and MOLE than with CAVER, especially at higher resolution in MolAxis. In a grid resolution of 0.4Å, CAVER found most previously identified channels11 in 64 hours whereas MolAxis found all previously determined channels with a similar resolution in less than two seconds. In the lowest calculated grid resolution of 0.8Å, CAVER found most channels in 57 minutes while MolAxis completed the calculation in less than two seconds (see Table 1). Note that some channels appear and disappear in different resolutions. CAVER finds substrate channel 2c only at resolutions 0.6Å and 0.7Å, substrate channel 2f at 0.4Å resolution and the water channel, denoted W, at 0.4Å to 0.7Å resolutions (see Table 1). MolAxis results are more consistent: channels that are found at one resolution are usually found also at other resolutions. The MOLE tool works with a fixed resolutions of about 0.4Å. It should be noted that channel 2b is found by MolAxis from resolution 0.3Å and lower and is not identified in 0.1Å and 0.2Å (see Table 1). This stems from the fact that channel 2b is narrow and quite close to the wider channel 2a and at high resolutions it gets overshadowed by channel 2a (see Discussion). The solvent channel (denoted S), is detected in the User mode from resolutions 0.3Å and lower as the eleventh pathway and thus does not appear in Table 1.

B. Human CYP3A4

MolAxis, CAVER and MOLE were run on human CYP3A4 (PDB code 1W0E) as in the CYPcam and the outputs of all runs are summarized in Table 2. The main difference between CYPcam and CYP3A4 is that the latter has a larger active site, and can oxidize many substrates with diverse chemical structures and is not as specific as CYPcam. The user starting point for all tools was 4Å above the heme iron at the center of active site. Again we compare the User with the Caver and Mole runs as in the bacterial P450 example. Within the first 10 identified pathways, MolAxis identified all channels and MOLE and CAVER identified channels 2a, 2b, 2e in all runs and channel S was identified twice only in the 0.7Å resolution and by MOLE (see Table 2). CAVER and MOLE did not detect channels 2c, 2f, 3 and W in all runs and even after running CAVER and MOLE trying to find 40 pathways, some channels were undetected. However, CAVER detected channels 2b and 2e six and four times in resolutions 0.3Å and 0.4Å, respectively and MOLE detected channels 2b and 2e three and five times, respectively in the first 10 identified channels. CAVER and MOLE tend to identify the same channel multiple times, making it difficult for the user to identify a more closed channel. In contrast, the corridors reported by MolAxis are unique geometric entities. Table 3 enumerates the MolAxis, MOLE and CAVER identified corridors of CYP3A4 at a resolution of 0.4Å. The channels are ranked according to the flux weight of their corresponding corridor sorted in descending order, i.e., the corridor of the first channel (numbered 1) is the shortest and widest corridor etc. In the MolAxis User mode, channel 2e is the first channel followed by channels 2b, 2c, 2a, 3 etc. It can be seen that the order of the channels in the MolAxis output is roughly conserved among the User and Auto runs. The first 10 identified pathways of MolAxis are in general unique, in contrast to CAVER and MOLE for which channels 2b and 2e are reported multiple times. MOLE overcomes this problem by clustering similar channels. Nonetheless, in order to enrich channel types in multiple channel systems as in the P450s, the user needs to search for many channels. As stated earlier, the corridors tagged as ‘other’ are geometrically feasible routes and thus might be new and to date unknown channels.

In addition, MolAxis identified new channels not identified previously. For example, at 0.8Å resolution MolAxis discovered two channels in the User mode and one channel in the Auto mode that are previously unreported. It still remains unclear whether those geometrically feasible new channels are biological relevant. All known channels of CYP3A4 detected by MolAxis are depicted in Figure 5. The CAVER and MOLE results remained the same after running them with three different starting points including the MolAxis starting point found automatically by the Auto mode (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Surfaces of the CYP3A4 detected channels according to MolAxis. CYP3A4 is represented by ribbons and the heme prosthetic group is represented as VDW and colored orange. Each channel surface is colored in a different color for the sake of clarity.

C. MD simulation analysis of the human CYP3A4 by MolAxis

CYP3A4 enzyme can catalyze a wide variety of reactions, such as hydroxylation, epoxidation or heteroatom oxidation, dealkylations for a given substrate.43 CYP3A4 has a large active site inside the core of the protein and can oxidize many substrates with diverse chemical structures. The enzyme has several substrate channels connecting the active site to the bulk solvent11 whereby the substrate enters and the product exits. As CYP3A4 metabolizes an immense amount of drugs, it is of major importance to try and understand how substrates/products enter/exit the enzyme and thus better control pharmacokinetics parameters in drug discovery. Enzyme dynamics and motions which may control the opening and closing of channels are not apparent in static crystal structures and may be missed in structural analysis. In addition, changes in the dimensions of viewable channels may be overlooked. MD simulation is a good tool for assessing channel movements along time and for comprehension of the channel gating mechanism and the (cooperative) behavior of residues involved in its opening and closing. In P450s, the most flexible regions are the BC loop and FG helices that form several substrate channels (see Figure 4), and their motions allow substrates to enter and products to leave the active site.44 The efficiency and accuracy of MolAxis have led us to investigate the channel dynamics in the human CYP3A4 isoform (PDB code 1TQN). We have previously carried out a 6 ns simulation of the substrate-unbound human CYP3A445 in a box of explicit solvent water molecules using periodic boundary conditions with the CHARMM force field.46 The enzyme was heated to 310K and a time step of 1fs was applied. We used a canonical NVT of MD simulation and applied a full electrostatic calculation using the Particle Mesh Ewald summation.47 Trajectory snapshots were taken every 10ps and served as input structures for MolAxis. We used the Auto mode to find the largest cavity (which is the active site) and to detect all channels emanating from it to the bulk solvent. Again all channels detected were denoted as in the previous P450 examples (Figure 5).

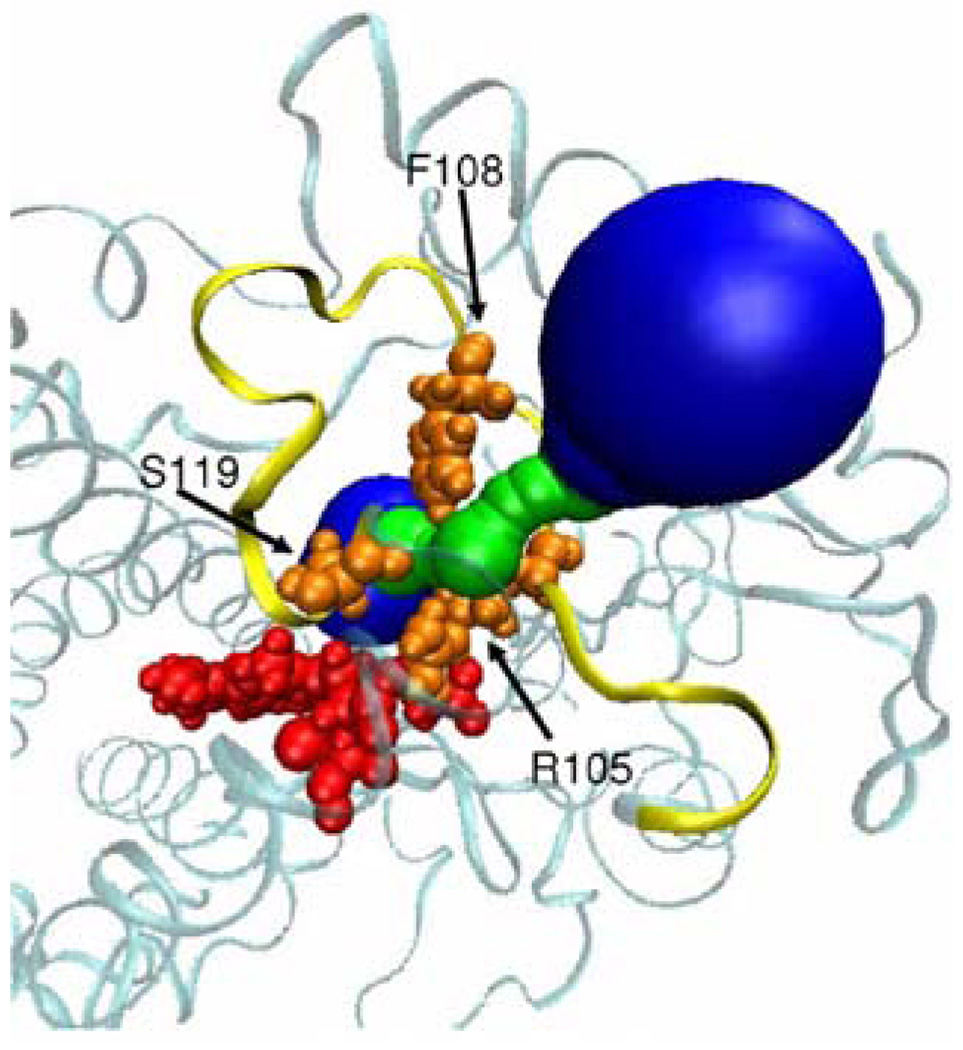

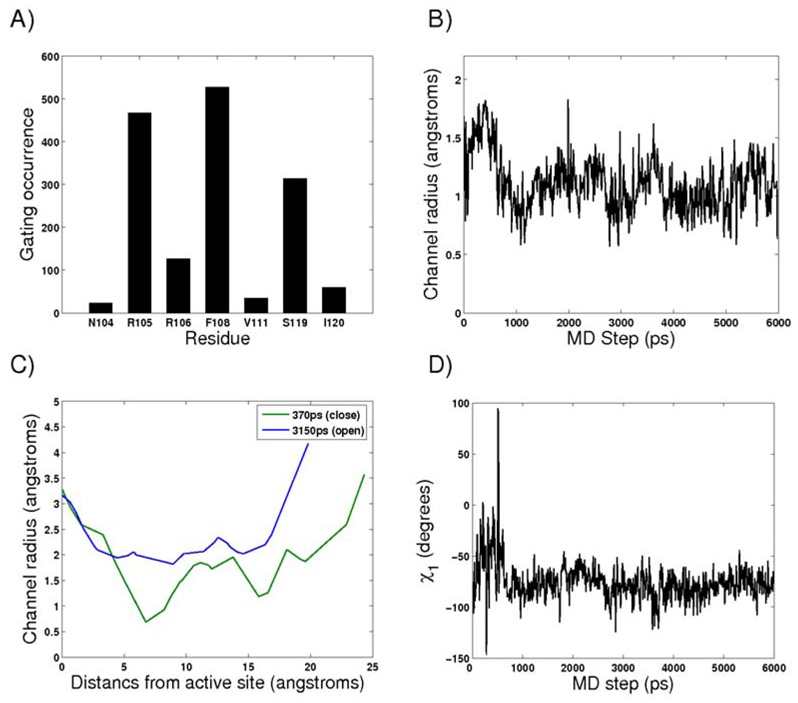

In most simulation snapshots (∼95 %) MolAxis detected the center of the active site of the human CYP3A4 as the largest void. The rest of the snapshots were overlooked as their largest detected cavities were not placed in the middle of the active site and thus not biologically significant. As there are many substrate channels we simplified this example by focusing on one substrate channel denoted 2e that penetrates through the BC loop in all P450s (see Figure 4, Figure 6) although the results can be analyzed for each substrate or water channel. The major goal of this analysis is to obtain better insights into the gating mechanism of the 2e substrate access channel. We calculated the corridor surface, bottleneck radius and lining residues of channel 2e along time. The three major gating residues that form the bottleneck of channel 2e are R105, F108 and S119 of the BC loop (Figure 7a). As can be seen from Figure 7b, the 2e channel is more open at the beginning of the simulation; subsequently, after 700ps of simulation its dimensions decrease to around 1Å radius on average. The entire surface of channel 2e is depicted in Figure 6. The largest bottleneck radius, 1.81Å, was found after 370 ps of simulation, and this structure was denoted as ‘open’; and the smallest, 0.68Å, was after 3150ps and was denoted ‘closed’ (Figure 7c). Figure 7d depicts the F108 side chain rotatable dihedral angle χ1 values along the simulation. We superimposed the Cα atoms of both open (370ps snapshot) and closed (3150ps snapshot) structures to see which structural determinants control the difference in bottleneck radius sizes. According to Figure 8, both R105 and S119 have similar conformations in the open and closed snapshots. F108 forms the major difference between the open and closed snapshots and manifests a different rotatable side chain angle. F108 is the bulkiest residue of the 2e channel gate and different rotamers of this residue can shift between an opening and closing of the 2e channel (Figure 8). The channel 2e radius size fluctuations are correlated to the F108 χ1 values along the simulation (Figures 7b, 7d) and it seems that after this angle is stabilized, the channel 2e radius values decrease and stay around 1.0Å.

Figure 6.

Surface of 2e channel in the CYP3A4 protein as calculated by MolAxis. The protein is represented as a ribbon. The BC loop is colored yellow. The heme is represented by its VDW and colored red, and the bottleneck residues (R105, F108 and S119) are represented by their VDW radii and colored orange. Channel surface patches with a radius less than 2.7Å are colored green, otherwise blue.

Figure 7.

a) CYP3A4 channel 2e bottleneck residues propensities after 6ns of MD simulation. b) Bottleneck radius profile of channel 2e of CYP3A4 along the simulation. c) Channel 2e radius profile from snapshots after 370ps (blue-open) and 3150ps (greenclosed) simulation. d) F108 χ1 angle values along 6ns simulation.

Figure 8.

Cα superimposition of the open snapshot after 370ps of MD simulation (blue) and the closed snapshot after 3150 ps simulation (yellow). The protein structures are represented as ribbons. The heme is represented by its VDW radius and colored red and the bottleneck residues are represented as sticks.

We conclude that by altering its rotatable torsion angle F108 can control the opening of the 2e substrate channel by positioning its phenyl moiety in and out of channel 2e bottleneck. This observation is supported by a previous simulation in the presence of an inhibitor inside the active site48 where F108 was observed as a gate keeper with an egress of an inhibitor from the active site through channel 2e. Site directed mutagenesis of residue F108 changed the regioselectivity of midazolam hydroxylation even though the residue is located far from the center of the reaction.49 These findings further support F108 as being a residue that interacts with substrates while passing through channel 2e toward the active site in CYP3A4.

Discussion

Channel and Corridor Correspondence

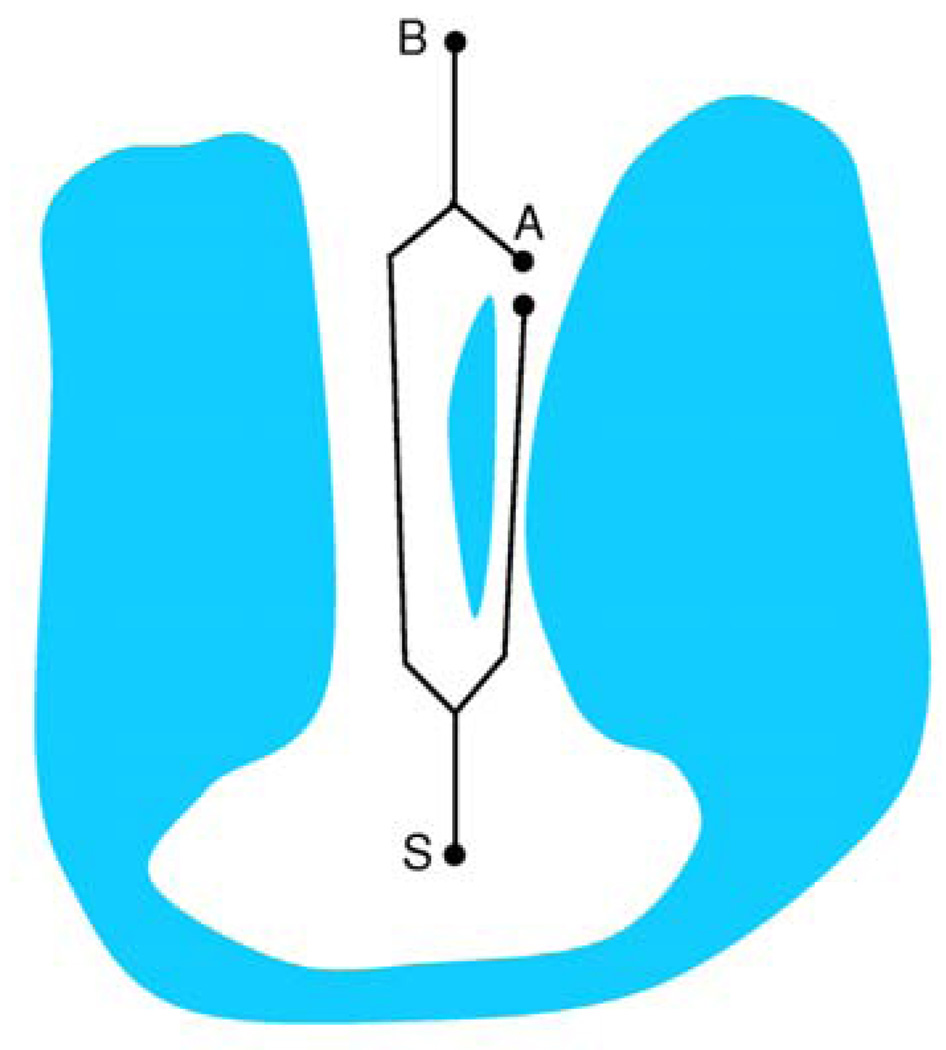

Recall that a corridor can exist without a corresponding channel, i.e., with no known biological related data, consequently pointing to a potential newly discovered channel. Interestingly, the opposite is also possible. In cases where a channel is closed or almost closed, the corridors that pass through it might actually be dead-end corridors. We call this phenomenon overshadowing and it occurs when the mouth of a narrow channel is close to the mouth of a wide channel. In this case we say that the wide channel overshadows the narrow channel.

For example, let us consider a conformation in which there are two channels, one wide and one narrow, which leave the chamber in about the same direction. Let us focus on a vertex in the pathway graph that lies in the mouth of the narrow channel, such that any pathway passing through the narrow channel must pass through it; see Figure 9 for an illustration. Assume that there are two pathways reaching the vertex in the pathway graph. The first pathway passes through the narrow channel and reaches the vertex. The other pathway passes through the wide channel, then passes close to the outer surface of the molecule and finally reaches the vertex. This detour can happen within the convex hull of the molecule, i.e., along a groove. The narrow channel will be reported as open if the optimal pathway (in flux weight terms) is the one going through the narrow channel, otherwise it will be reported as closed. This explains the observation that channel 2b of CYPcam is reported as open in some of the runs (see Table 1). Channel 2b is narrow and its mouth is proximal to the mouth of the wider channel 2a. At some resolutions channel 2a overshadows channel 2b, making the corridors that pass through channel 2b dead-end corridors, thus reporting channel 2b as closed. The overshadowing phenomenon can be interpreted as an artifact of the method that may be solvable by fine-tuning the parameters that we use. In fact it points to a major question for future work: How to adapt our method such that a variety of biological insights concerning pathways can be incorporated into the search algorithm. For example, we may look for an alternative balance between path width and path length in weighing the tree edges.

Figure 9.

Illustration of an overshadowed channel. The corridor tree is depicted using black lines, S is the root vertex, A is a vertex close to the mouth of the narrow right channel and B is a boundary vertex. Since the left channel is wide the shortest corridor reaching vertex A passes through the left wide channel. Therefore there are no boundary corridors passing through the right channel and it is reported as closed.

Geometric Convergence

Corridors found by MolAxis lie close to the medial axis of the complement of the molecule. We found that the computed corridors are not always identical at different resolutions. This happens since the medial axis is composed of surface patches, which leaves some freedom in choosing the one-dimensional pathways. Even when moving on the medial axis there might be numerous pathways that cross a channel, with a similar flux weight. We observed that at high resolution of less than 0.05Å, the corridor tree seems to converge (data not shown). Even so, we note that the seemingly different corridors which are obtained at low resolutions have similar features, e.g., they pass near the same amino acids and have similar profiles. Therefore we conclude that MolAxis can be run at low resolutions (such as 0.1–0.5Å).

Comparison with CAVER

We compare our approach to a grid-based approach as implemented in the CAVER tool. CAVER defines a three-dimensional grid covering the convex hull of the given molecule (represented by a union of balls). Each grid cell is then marked as inner or outer to the molecule, according to the center of the grid cell. All inner grid cells are discarded. The centers of the outer grid cells are set as vertices of a graph. CAVER connects neighboring grid vertices with an edge, and gives weights to the vertices according to their distance to the surface of the molecule, giving a smaller weight to points that are more distant from the VDW surface of the molecule. The corridors are computed using a version of Dijkstra’s algorithm, similar to the one we use. The main difference from our approach is the number of vertices needed for the approximation. While limiting ourselves to the medial axis which is a two-dimensional entity, we construct many fewer vertices, which explains the extremely large difference in the running time between the two programs (from a couple of seconds of our program up to hours of CAVER, on the same input, see Table 1 and Table 2). This huge difference allows to apply MolAxis along molecular dynamic trajectories, allowing us to follow the channel dynamics. The pathways found by CAVER are close to the medial axis, which means that the grid points sampled far from the medial axis were actually not needed. Even so, note that this is not a property of all weight functions. For example, if the goal is to minimize a user-specified energy function, the desired pathway might not necessarily be close to the medial axis. A grid based approach can handle such a case whereas our approach would probably miss the desired pathway.

Comparison with HOLE

The HOLE method finds a possible route for a ball squeezing through the channel (changing its radius as it passes). Given a starting point in the channel cavity and a channel vector, which is a vector in the direction of the channel, HOLE moves a plane P(t) that is orthogonal to the channel vector in steps along the vector using a parameter t. We denote by Sopt(t) the largest sphere centered at P(t) which can be accommodated in the channel without overlap with the VDW surface of the molecule. For each plane P(t) HOLE uses a Monte Carlo simulated-annealing procedure to construct a sphere S(t) on the plane P(t) that is close to Sopt(t). This procedure is iterated in the direction of the channel vector until a series of sphere positions is generated that represents the channel.

Note that the center of Sopt(t) is actually the point of the medial axis centered at the plane P(t) with the highest clearance. We analyze HOLE in two theoretical aspects. First, due to the non deterministic nature of the Monte Carlo procedure, S(t) might in fact be far away from Sopt(t). Second, since the optimization is done separately for each plane the computed pathway can be erratic or `zigzagging’, as seen in Figure 3b. Furthermore, even if we assume that HOLE managed to find Sopt(t) the resulting pathway might exhibit an unwanted behavior. For the sake of the discussion let us extend the function Sopt(t) from a discrete set of t values to a continuous range of real values. Due to the properties of the medial axis the function Sopt(t) is not necessarily continuous in t. This explains the `jumps’ that sometimes occur in the pathways computed by HOLE. We conclude that the optimization done by HOLE can be seen as a clearance-only optimization. In contrast, the pathways that MolAxis constructs are continuous, and due to the global optimization approach the pathways balance between length and clearance.

Comparison with MOLE

When the manuscript was ready for submission, a newly published paper presented the MOLE19 method. Consequently, we carried out a comparison between the two methods. The MOLE method utilizes the Voronoi diagram of the atom centers. It uses the vertices and edges of the diagram to construct a graph, and it sets a weight on each edge in a manner similar to ours, taking into account the length and clearance of the edge. The two main differences between our method and the MOLE method are described below:

(1) The MOLE method does not have a user-defined resolution; instead it treats the atoms as if they were all of a fixed size, introducing an error which depends on the difference between the largest and smallest input atom. In cases where hydrogen atoms are discarded the error can be as small as 0.4Å, yet for cases which include a combination of heavy and light elements the error can be as high as 2Å. In contrast, our method allows the user to control the resolution, with hardly any effect on the efficiency of the algorithm, and can therefore be seen in this sense as a combination of the pros of CAVER and of MOLE.

(2) In the MOLE algorithm, after reporting a channel, its edges are updated by adding a ‘penalty’ weight to each in order to reduce the chances of reporting these edges again. Then, Dijkstra’s algorithm is applied again and the new shortest path is reported. This new shortest path might be similar to one of the previously reported shortest paths (see Table 3). This results in the need to apply clustering techniques on the output channels, leaving the user to decide which of the output channels are in fact the same channel. In contrast, our approach computes all channels in one run of Dijkstra’s algorithm, and similar channels are discarded using the forking threshold as described in the Theory and Algorithm Section (see Figure 10 for an illustration).

Figure 10.

Illustration of the function of the forking threshold. A corridor tree is depicted using black lines with S as its root vertex. We depict the bounding circle of the molecule and a concentric circle with a radius equal to the user-defined forking threshold, by two dashed circles. Three pathways denoted by P1,P2 and P3 are sorted according to their flux weight. The forking vertex of P1 and P2 is denoted by F. Since the distance of F is larger than the forking threshold, pathway P2 is considered similar to P1 and therefore is discarded. By increasing the forking threshold the user can cause P2 to also be reported, thus raising the level of detail.

Conclusions

This paper introduced MolAxis, a tool for the efficient identification of channels in the complement of molecules. We described the theoretical background and the algorithm implemented in MolAxis. Here MolAxis was utilized to analyze static proteins and snapshots along an MD simulation trajectory. Our method is both efficient and most sensitive in term of channel detection in macromolecules as compared to previously developed tools. MolAxis takes into account the global geometry of the protein. It detected accurately TM channels in an LPC protein and ABC transporter resulting in a relatively smooth pathway and pointed to the main biological TM channel. MolAxis was found to efficiently detect open to almost closed substrates- and water- channels leading from the P450s isozymes active sites to their surfaces. It identifies unique geometric channels and as such does not suffer from multiplicity and generates non- redundant shapes and structures of channels connecting active sites of enzymes to their surfaces. We have applied MolAxis to a large number of MD simulation snapshots of the human CYP3A4 enzyme to obtain insight into the channels dynamics and gating mechanisms along time. We observed that perturbation of the phenyl rotatable dihedral angle of F108 in substrate channel 2e controls the opening and closing of that channel allowing us to propose a mechanism involving F108 for the gating of this channel. F108 was previously suggested to be a gate keeper of channel 2e. We expect that MolAxis will be utilized for understanding substrate selectivity, and for gaining better insights into mechanisms of transport as well as in drug design.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Isaiah Arkin and Itamar Kass for discussions of the specifications of such a computational tool in the context of transmembrane proteins. This work has also been supported in part by the IST Programme of the EU as Sharedcost RTD (FET Open) Project under Contract No IST-006413 (ACS - Algorithms for Complex Shapes), by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 236/06), and by the Hermann Minkowski—Minerva Center for Geometry at Tel Aviv University. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Laskowski RA. SURFNET: A program for visualizing molecular surfaces, cavities, and intermolecular interactions. J Mol Graph. 1995;13:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendlich M, Rippmann F, Barnickel G. LIGSITE: Automatic and efficient detection of potential small molecule-binding sites in proteins. J Mol Graph Model. 1997;15:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(98)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levitt DG, Banaszak LJ. POCKET: A computer graphics method for identifying and displaying protein cavities and their surrounding amino acids. J Mol Graph. 1992;10:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(92)80074-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:178–185. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang J, Edelsbrunner H, Woodward C. Anatomy of protein pockets and cavities: Measurement of binding site geometry and implications for ligand design. Protein Science. 1998;7:1884–1897. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkatachalam CM, Jiang X, Oldfield T, Waldman M. LigandFit: A novel method for the shape-directed rapid docking of ligands to protein active sites. J Mol Graph Model. 2003;21:289–307. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(02)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurie ATR, Jackson RM. Q-SiteFinder: An energy-based method for the prediction of protein-ligand binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1908–1916. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakoncic J, Jouanneau Y, Meyer C, Stojanoff V. The crystal structure of the ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase from Sphingomonas CHY-1. FEBS J. 2007;274:2470–2481. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verschueren KH, Seljee F, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Dijkstra BW. Crystallographic analysis of the catalytic mechanism of haloalkane dehalogenase. Nature. 1993;363:693–698. doi: 10.1038/363693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CK, Madauss K, Lian W, Beck MR, Tolbert WD, et al. Structure of neurolysin reveals a deep channel that limits substrate access. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3127–3132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051633198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cojocaru V, Winn PJ, Wade RC. The ins and outs of cytochrome P450s. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Axelsen PH, Harel M, Silman I, Sussman JL. Structure and dynamics of the active site gorge of acetylcholinesterase: Synergistic use of molecular dynamics simulation and X-ray crystallography. Protein Science. 1994;3:188–197. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephenson FA Ion channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1991;1:569–574. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard EA. Receptor classes and the transmitter-gated ion channels. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:368–374. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90002-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saier MH. A functional-phylogenetic system for the classification of transport proteins. J Cell Biochem. 1999;75:84–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1999)75:32+<84::aid-jcb11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savarese TM, Fraser CM. In vitro mutagenesis and the search for structure-function relationships among G protein-coupled receptors. Biochemistry Journal. 1992;283:1–19. doi: 10.1042/bj2830001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smart OS, Goodfellow JM, Wallace BA. The Pore Dimensions of Gramicidin A. Biophysical Journal. 1993;65:2455–2460. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81293-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrek M, Otyepka M, Banas P, Kosinova P, Koca J, et al. CAVER: A New Tool to Explore Routes from Protein Clefts, Pockets and Cavities. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:316–324. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrek M, Kosinová P, Koca J, Otyepka M, et al. MOLE: a Voronoi diagram-based explorer of molecular channels, pores, and tunnels. Structure. 2007;15:1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelsbrunner H, Mücke EP. Three-dimensional alpha shapes. ACM Trans Graphics. 1994;13:43–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelsbrunner H, Facello MA, Liang J. On the definition and the construction of pockets in macromolecules. Discrete Applied Mathematics. 1998;88:83–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attali D, Boissonnat JD, Edelsbrunner H. Stability and computation of medial axes: a state-of-the-art report. In: Möller BHT, Russel B, editors. In Mathematical Foundations of Scientific Visualization, Computer Graphics and Massive Data Exploration. Springer-Verlag, Mathematics and Visualization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaffe E. M.Sc. Thesis. Tel Aviv University; 2007. Efficient construction of pathways in the complement of the union of balls in R3. at http://www.cs.tau.ac.il/~eitanyaf/thesis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieutier A. Any open subset of Rn has the same homotopy type than its medial axis. Procceedings of the Symposium on Solid Modeling and Applications. 2003:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boissonnat JD, Delage C. Convex hull and Voronoi diagram of additively weighted points. ESA Proceedings. In: Brodal GS, Leonardi S, editors. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: 2005. pp. 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numerische Mathematik. 1959;1:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edelsbrunner H, Letscher D, Zomorodian A. Topological persistence and simplification. Discrete and Computational Geometry. 2002;28:511–533. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The CGAL Manual. 2007 Release 3.3, www.cgal.org.

- 29.Hamphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Molec Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bransburg-Zabary S, Gutman ENM. The most probable trajectory for ion flux through large-pore channel. Solid State Ionics. 2004;168:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locher KP. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Meer G. The structures of MsbA: Insight into ABC transporter-mediated multidrug efflux. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1042–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guengerich FP. In cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism and Biochemistry. In: Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. 3rd edition. New York: Plenum press; 2005. pp. 377–531. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wrighton SA, Stevens JC. The human hepatic cytochrome P450 involved in drug metabolism. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1992;22:1–21. doi: 10.3109/10408449209145319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaik S, Kumar D, de Visser SP, Altun A, Thiel W. Theoretical Perspective on the Structure and Mechanism of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2279–2328. doi: 10.1021/cr030722j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loida PJ, Sligar SG. Molecular recognition in cytochrome P450: mechanism for the control of uncoupling reactions. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11530–11538. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schleinkofer K, Sudarko, Winn PJ, Lüdemann SK, Wade RC. Do mammalian cytochrome P450s show multiple ligand access pathways and ligand channelling? EMBO. 2005;6:584–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlichting I, Jung C, Schulze H. Crystal structure of cytochrome P-450cam complexed with the (1S)-camphor enantiomer. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yano JK, Wester MR, Schoch GA, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, et al. The Structure of Human Microsomal Cytochrome P450 3A4 Determined by X-ray Crystallography to 2.05-Å Resolution. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38091–38094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, et al. Crystal structures of human Cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to Metyrapone and Progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekroos M, Sjögren T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13682–13687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wrighton SA, Schuetz EG, Thummel KE, Shen DD, Korzekwa KR, et al . The human CYP3A subfamily: Practical considerations. Drug Metab Rev. 2000;32:339–361. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guengerich FP. Common and Uncommon Cytochrome P450 Reactions Related to Metabolism and Chemical Toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poulos TL. Cytochrome P450 flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13121–13122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336095100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fishelovitch D, Hazan C, Shaik S, Wolfson HJ, Nussinov R. Structural Dynamics of the Cooperative Binding of Organic Molecules in the Human Cytochrome P450 3A4. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1602–1611. doi: 10.1021/ja066007j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Evanseck JD, et al. Allatom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen HG. Accuracy and efficiency of the particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:3668–3679. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Liu H, Luo X, Zhu W, Tang Y, et al. Possible pathway(s) of metyrapone egress from the active site of cytochrome P450 3A4: a molecular dynamics simulation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:689–696. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.014019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan KK, He YQ, Domanski TL, Halpert JR. Midazolam Oxidation by Cytochrome P450 3A4 and Active-Site Mutants: an Evaluation of Multiple Binding Sites and of the Metabolic Pathway That Leads to Enzyme Inactivation. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:495–506. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]