Abstract

Experimental evidence documents that nutritional phytoestrogens may interact with reproductive functions but the exact mechanism of action is still controversial. Since quercetin is one of the main flavonoids in livestock nutrition, we evaluated its possible effects on cultured swine granulosa cell proliferation, steroidogenesis, and redox status. Moreover, since angiogenesis is essential for follicle development, the effect of the flavonoid on Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor output by granulosa cells was also taken into account. Our data evidence that quercetin does not affect granulosa cell growth while it inhibits progesterone production and modifies estradiol 17β production in a dose-related manner. Additionally, the flavonoid interferes with the angiogenic process by inhibiting VEGF production as well as by altering redox status. Since steroidogenesis and angiogenesis are strictly involved in follicular development, these findings appear particularly relevant, pointing out a possible negative influence of quercetin on ovarian physiology. Therefore, the possible reproductive impact of the flavonoid should be carefully considered in animal nutrition.

1. Introduction

Quercetin (3,30,40,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone) is a flavonoid belonging to a group of plant-derived nonsteroidal compounds known as phytoestrogens [1]. In plants, these compounds are involved in energy production and exhibit strong antioxidant properties; in mammals, they have been shown to exert various biological and pharmacological effects [2, 3]. Several studies [4–6] have demonstrated their significant health promoting activities, due to free radical scavenging and metal chelating properties. On the other hand, quercetin can also exhibit pro-oxidant effects [7]. It has been demonstrated [8–11] a relationship between quercetin free radical scavenging activity and its anticarcinogenic and anti-inflammatory properties. Most experimental data about the activity of flavonoids in different biological systems have been obtained by in vitro studies, and the knowledge of the pharmacokinetics and systemic availability of food-derived flavonoids in humans and animals is still incomplete: in particular, the bioavailability of quercetin appears low, but reported values range from 0% to 52% [12, 13].

Recent data obtained in vitro or in animal studies indicate that flavonoids may also modify cell function independently of their antioxidant power [14–16], affecting the overall process of carcinogenesis by different mechanisms. Since it is well known that neovascularization represents a key process in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis, a lot of scientific interest has developed in recent years about potential inhibitors of angiogenesis. Among natural health products, dietary flavonoids have shown to possess antiangiogenic effects, inhibiting several important steps of new vessel growth: an impairment of VEGF expression by different flavonoids has been documented [17, 18], as well as inhibitory effects on proliferation, migration, tube formation of endothelial cells in vitro [19–21].

In particular, many experimental evidences suggest a close link between quercetin antineoplastic effect and its antiangiogenic potential [22–25]. While both the antioxidant and antiangiogenic properties of quercetin are generally related to its protective effects against oxidative stress and should also be relevant for its cancer preventive impact [11, 26], the potential of the inhibition of vessel formation on female reproductive efficiency remains elusive; in fact, it is well known that the ovarian angiogenic process is strictly associated with follicular development [27]. Furthermore, ROSs play a crucial role in the ovarian follicle as signalling molecules in both the angiogenic cascade [28] and the ovulatory process. Additionally, phytoestrogens are able to bind to estrogen receptors thus activating several estrogen-responsive genes [3]. In particular, quercetin has been found to exhibit both estrogenic and antiestrogenic actions in vitro thus suggesting different potential effects on reproductive function.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate possible effects of quercetin on the function of granulosa cells, which play a complex and fundamental role in the development of the ovarian follicle. To this purpose, we studied the flavonoid action on granulosa cell proliferation, steroidogeneis, and redox status. Finally, since follicle growth requires new vessel formation, we also evaluated the effect of quercetin on the production of VEGF, the main proangiogenic factor.

2. Materials and Methods

All the reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo, USA) unless otherwise specified.

2.1. Granulosa Cell Culture

Swine ovaries were collected at a local slaughterhouse, placed into cold PBS (4°C) supplemented with penicillin (500 IU/mL), streptomycin (500 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (3.75 μg/mL), maintained in a freezer bag and transported to the laboratory within 1 hour. After two washings with PBS and ethanol (70%), granulosa cells were aseptically harvested by aspiration from follicles >5 mm with a 26-gauge needle and released in medium containing heparin (50 IU/mL), centrifuged for pelleting and then treated with 0.9% prewarmed ammonium chloride at 37°C for 1 minute to remove red blood cells. Cell number and viability were estimated using a haemocytometer under a phase contrast microscope after vital staining with trypan blue (0.4%) of an aliquote of cell suspension. Cells were seeded at different densities (see below) in culture medium (CM) represented by M199 supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (2.2 mg/mL), bovine serum albumin (0.1%), penicillin (100 UI/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), amphotericin B (2.5 μg/mL), selenium (5 ng/mL), and transferrin (5 μg/mL). Cells were treated with quercetin (C15H10O7; CAS number 117-39-5; purity >95%; Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA) at the concentrations of 5 or 50 μg/mL and incubated at 37°C under humidified atmosphere (5% CO2) for 48 hours.

Quercetin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the final concentration of DMSO added to the medium was 0.2% (vol/vol). The same concentration of DMSO was added to specific control wells.

2.2. Granulosa Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was evaluated by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay test (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Briefly, 104 cell/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and treated as described above. After addition of 20 μL BrdU to each well during the last 4 hour of incubation, culture media were removed, and DNA denaturing solution was added in order to improve the accessibility of the incorporate BrdU for antibody detection. Thereafter, 100 μL anti-BrdU antibody were added to each well. After a 1.5-hour incubation at room temperature (21°C), the immune complexes were detected by the subsequent substrate reaction. The reaction product was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm against 690 nm using Spectra Shell Microplate reader (SLT Spectra, Milan, Italy). To establish viable cell number, absorbance was related to a standard curve prepared by culturing in quintuplicate granulosa cells at different plating densities (from 103 to 105/200 μL) for 48 hours. The curve was repeated in four different experiments. The relationship between cell number and absorbance was linear (r = 0.92). Cell number/well was estimated from the resulting linear regression equation. The assay detection limit was 103 cell/well, and the variation coefficient was less than 5%. The number of cells obtained by this calculation was used for correcting hormones, VEGF production, and redox status data.

2.3. Steroid Production

Briefly, 104 cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates in 200 μL CM supplemented with androstenedione (28 ng/mL) and treated with quercetin at concentrations previously described. Culture media were collected after incubation, frozen and stored at −20°C until progesterone (P4) and 17β estradiol (E2) determination by validated RIAs [29]. P4 assay sensitivity and ED50 were 0.24 and 1 nM/L, respectively; E2 assay sensitivity and ED50 were 0.05 and 0.2 nM/L. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 12% for both assays.

2.4. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species

2.4.1. Nitric Oxide Production

Nitric oxide (NO) was assessed by measuring nitrite levels in culture media by microplate method based on the formation of a chromophore after reaction with Greiss reagent, which was prepared fresh daily by mixing equal volumes of stock A (1% sulfanilamide, 5% phosphoric acid) and stock B (0.1% N-[naphtyl] ethylenediamine dhydrochloride). Briefly, 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with quercetin as already mentioned. After incubation with Greiss reagent, the absorbance was determined with a Spectra Shell Microplate Reader using a 540 nm against 620 nm filter. A calibration curve ranging from 25 to 0.39 μM was prepared by diluting sodium nitrite in culture medium.

2.4.2. Superoxide Anion Production

Superoxide anion (O2−) generation was measured by the cell proliferation WST-1 test (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Briefly, 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with quercetin as described above. Since evidence exists [30, 31] that tetrazolium salts can be used as a reliable measure of intracellular O2− production, 20 μL of WST-1 were added to the cell during the last 4 hours of incubation. The absorbance was then determined using a Spectra Shell Microplate reader at 450 nm against 620 nm.

2.4.3. Hydrogen Peroxide Production

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production was measured by an Amplex Red Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, PoortGebouw, The Netherlands); the Amplex Red reagent reacts with H2O2 to produce resorufin, an oxidation product. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates. After incubation with treatments, plates were centrifuged for 10 minutes, at 400 × g, then the supernatants were discarded and cells were lysed by adding cold Triton 1% in Tris–HCl (100 μL per well), incubating on ice for 30 minutes. The test was performed on cell lysates and read against a standard curve of H2O2 ranging from 0.195 to 12.5 μM. A Spectra Shell microplate reader set to read 540 nm emission was used to quantify the reaction product.

2.5. Scavenging Enzyme Activity

2.5.1. Superoxide Dismutase Activity

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined by an SOD Assay Kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Japan). Briefly, 2 × 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and, after treatments, the plates were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 400 × g. The supernatants were discarded and cells were lysed by adding cold Triton 1% in Tris–HCl (100 μL/105 cells) and incubating on ice for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were tested without dilution, and a standard curve of SOD ranging from 0.156 to 20 U/mL was prepared. The colorimetric assay was performed measuring formazan produced by the reaction between a tetrazolium salt (WST-1) and a superoxide anion (O2−), produced by the reaction of an exogenous xantine oxidase. The remaining O2− is an indirect hint of the endogenous SOD activity. The absorbance was determined with a Spectra Shell Microplate Reader reading at 450 nm against 620 nm.

2.5.2. Peroxidase Activity

Peroxidase activity was measured by an Amplex Red Peroxidase Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, PoortGebouw, The Netherlands) based on the formation of an oxidation product (resorufin) derived from the reaction between H2O2 given in excess and the Amplex Red reagent. Briefly, 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated in the conditions described above. After centrifugation for 10 minutes. at 400 × g, the supernatants were discarded, and cells were lysed by adding cold Triton 1% in TRIS HCl (100 μL/105 cells) and incubating on ice for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were used undiluted to perform the test. The absorbance was determined with a Spectra Shell Microplate Reader using a 540 nm filter and read against a standard curve of peroxidase ranging from 0.039 to 5 mU/mL.

2.6. Scavenging Nonenzymatic Activity

2.6.1. FRAP Assay

FRAP assay is a colorimetric method based on the ability of the antioxidant molecules to reduce ferric-tripiridyltriazine (Fe3+TPTZ) to a ferrous form (Fe2+TPTZ). Fe2+ is measured spectrophotometrically via determination of its coloured complex with 2,4,6-Tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (Fe2+ TPTZ). TPTZ reagent was prepared before use, mixing 25 mL of acetate buffer, 2.5 mL of 2,4,6-Tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) 10 mM/L in HCl 40 mM/L and FeCl3−6H2O solution.

Briefly, 2 × 105 cells/200 μL CM were seeded in 96-well plates and treated as already described. At the end, plates were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 400 × g, supernatants were discarded and cells were lysed by adding cold Triton 0.5% + PMSF in PBS (200 μL/well), incubating on ice for 30 minutes. The test was performed on 40 μL of cell lysates added to Fe3+ TPTZ reagent and then incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The absorbance of Fe2+ TPTZ was determined by Spectra Shell Microplate Reader at 595 nm. The ferric reducing ability of cell lysates was calculated by plotting a standard curve of absorbance against FeSO4−7H2O standard solution.

2.7. VEGF Production

The VEGF content in culture media was quantified by an ELISA (Quantikine, R & D System, Minneapolis, Mich, USA); this assay, which was developed for human VEGF detection, has been validated for pig VEGF [32]. Briefly, 106 cell/1 mL CM were seeded in 24-well plates and treated as described above. The assay sensitivity was 8.74 pg/mL, and the intra and interassay CVs were always less than 7%. The absorbance was determined with a Spectra Shell Microplate using a 450 nm filter.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least 4 times (6 replicates/treatment). Experimental data are presented as mean ± SEM; statistical differences were calculated with ANOVA using Statgraphics package (STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA). When significant differences were found, means were compared by Scheffè's F-test.

3. Results

3.1. Granulosa Cell Proliferation

BrdU incorporation assay test showed that basal swine granulosa cell proliferation was unaffected by both concentrations of quercetin.

3.2. Steroid Production

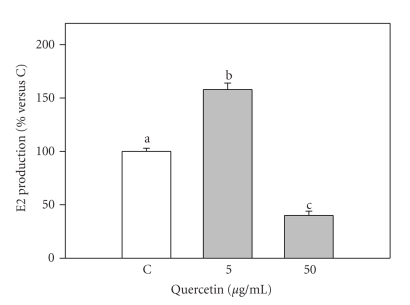

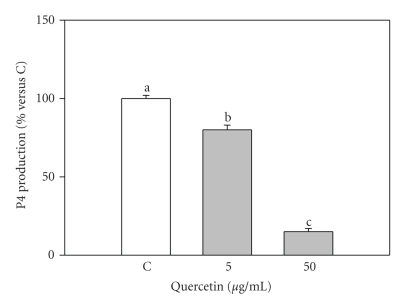

Basal steroid production by granulosa cells was 3.7 ± 0.6 and 71.8 ± 10.0 ng/mL (mean ± S.E.M.) for E2 and P4, respectively. 50 μg/mL quercetin significantly (P < .001) inhibited E2 production by granulosa cells; on the contrary, 5 μg/mL significantly increased E2 levels (Figure 1). Quercetin significantly (P < .001) inhibited P4 production by granulosa cells with a dose-dependent effect (P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on Estradiol 17β (E2) production by swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .001) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

Figure 2.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on progesterone (P4) production by swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .001) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

3.3. Reactive Oxygen Species Production

3.3.1. Nitric Oxide Production

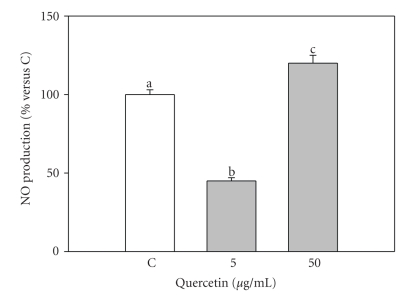

In the control group, NO basal levels were 3.16 ± 0.3 μM; 5 μg/mL quercetin significantly inhibited (P < .001) NO production, while 50 μg/mL significantly increased (P < .001) NO levels in granulosa cell culture media (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on nitric oxide production (NO) by swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .001) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

3.3.2. Superoxide Anion Production

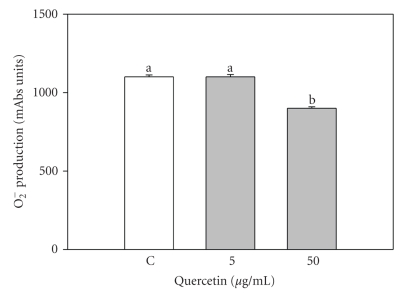

WST-1 assay showed that 50 μg/mL quercetin significantly (P < .05) inhibited O2− production, while 5 μg/mL were ineffective (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on superoxide anion (O2−) production by swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .05) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

3.3.3. Hydrogen Peroxide Production

Colorimetric assay did not show any significant effect of quercetin on H2O2 production by swine granulosa cell.

3.4. Scavenging Enzyme Activity

Superoxide Dismutase and Peroxidase Activity —

Both SOD and peroxidase activities were unaffected by quercetin.

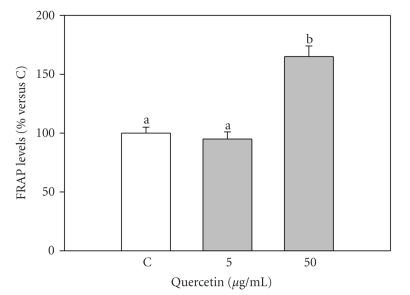

3.5. Scavenging Nonenzymatic Activity

FRAP Assay —

FRAP assay showed that 50 μg/mL quercetin significantly (P < .001) increased the nonenzymatic antioxidant power in granulosa cell, while 5 μg/mL were ineffective (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) levels in swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .001) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

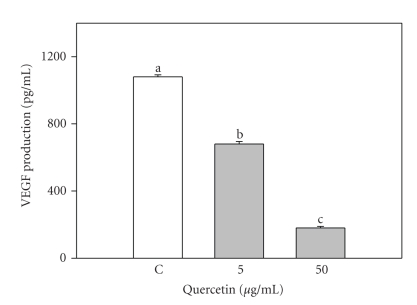

3.6. VEGF Production

VEGF production by swine granulosa cell was significantly (P < .05) inhibited by both concentrations of quercetin; higher dose produced more marked effects (P < .001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of the 48-hour treatment with quercetin (5 and 50 μg/mL) on Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) production by swine granulosa cell cultured in vitro. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six replicates/treatment repeated in four different experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < .001) calculated by ANOVA and Scheffè's F-test (Statgraphics package, STSC Inc., Rockville, Md, USA).

4. Discussion

Phytoestrogen quercetin is abundant in many plants used in animal nutrition [33, 34]. In recent years, this flavonoid has attracted a lot of interest, due to its putative health promoting activities likely resulting from its antioxidant effects. Nevertheless, its overall biological impact remains controversial, mostly because of limited information about its bioavailability, endogenous dynamics, and the relative contribution of different types of conjugates in humans and animals. Quercetin appears to be effective in in vitro assays at concentrations ranging from 0.3 and 30 μg/mL, but plasma levels resulting from high oral doses are generally below those values [13]. This issue needs to be properly assessed in future studies, in order to get a better insight on the optimal consumption levels which could provide pharmacological significant concentrations in body fluids and tissues.

In our experimental model, high quercetin concentration (30 μg/mL) has also been tested, since a process of accumulation of this flavonoid in some body tissues cannot be excluded [13].

Present study confirms that quercetin can modulate ovarian function, interfering with porcine granulosa cell steroidogenic activity [35]. The negative effect on P4 production could result from an inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes [36, 37], since no detectable changes of cell proliferation have been observed. In a previous work [37], it has documented that a suppressive action of quercetin on cytochrome P45, catalyzing the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, represents a rate-limiting step in the steroidogenic pathway. Several recent studies [35, 38, 39] show that the phytoestrogen-induced decrease of P4 production in granulosa cells could result from an inhibition of 3β-hydroxysteroid enzyme. On the contrary, Chen et al. [40] evidenced that quercetin increases StAR mRNA expression in MA-10 mouse tumor Leydig cells thus resulting in a stimulatory effect on steroidogenesis. This difference could be due to a cell type-dependent action of the flavonoid. As for E2 production, quercetin displayed a biphasic action: in fact, our data show that low dosages appear to increase E2 levels, while higher concentrations strongly decrease E2 production. An inhibitory effect of quercetin on aromatase activity in human granulosa-luteal cells has been documented [39], but the mechanisms through which this phytoestrogen could modulate the enzyme expression and activity remain elusive: these could involve either a binding with the estrogen receptors and/or a modulation of cell signalling pathways. On the basis of our data, it is possible to speculate that quercetin effects on E2 production by granulosa cells could be mediated by NO. In fact, this free radical seems to represent an autocrine regulator of granulosa cells E2 production [41], strongly inhibiting P450 aromatase activity [42]; the increase in estradiol secretion by cultured human granulosa cell [42] treated with NO synthase (NOS) inhibitors [43] would further strengthen this hypothesis. Interestingly, in agreement with our previous works [44, 45], current data document that quercetin at low doses strongly inhibits NO levels, while at higher doses it stimulates NO release. These overall data would indicate that quercetin can regulate aromatase activity , and thus E2 release, by an interference with the NO/NOS system in swine granulosa cells. Our results also document that the increase of NO levels after treatment with 50 μg/mL of quercetin is paralled by a decrease of O2− levels: this observation would suggest a possible relationship between these two ROSs. Quercetin has been shown [46] to protect nitric oxide (NO) from the scavenging actions of O2−; Vera et al. [47] reported that NO production negatively affects superoxide anion (O2−) accumulation with a resulting formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO). Even if the antioxidant potential of quercetin has been demonstrated by different studies [48, 49], pro-oxidative dose-dependent effects were also shown [7]. Present data indicate that quercetin does not affect neither H2O2 levels nor SOD activity. Since antioxidant scavenger gene expression depends mainly on ROS levels [50], both the inhibitory effect on O2− generation as well as the ineffectiveness in modulating H2O2 production could, respectively, explain the lack of effect on SOD and peroxidase enzyme activity. On the other hand, the higher quercetin concentration increased total nonenzymatic antioxidant ability thus suggesting that the antioxidant protection could result from an increased ability of several molecules to chelate transition metals [51].

Quercetin, at both concentrations tested, displayed a strong inhibitory effect on VEGF output thus suggesting its involvement in the modulation of angiogenesis. Since follicular development is strictly dependent on the angiogenic process [25], driven mainly by VEGF, this finding acquires particular relevance, since it is possible to speculate a possible negative influence of quercetin on ovarian physiology. In agreement with our findings, Zhong et al. [52] demonstrated that quercetin treatment significantly decreases VEGF secretion by myeloblastic leukemia cells NB4 in vitro. In addition, several studies document that flavonoids inhibit VEGF-induced endothelial cell functions and signalling pathways acting at molecular level [53–56]. Moreover, quercetin was found to inhibit several steps of angiogenesis, including proliferation, migration, and differentiation of endothelial cells [20, 57]. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that quercetin affects porcine granulosa cell function by interfering with steroidogenic activity and redox status as well as by inhibiting VEGF output; these data would suggest that this phytoestrogen represents a potential modulator of ovarian functions. Further studies are needed to better define the in vivo effects of quercetin on reproductive physiology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FIL and PRIN grants.

References

- 1.Moutsatsou P. The spectrum of phytoestrogens in nature: our knowledge is expanding. Hormones. 2007;6(3):173–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo S-M. Flavonoids and gene expression in mammalian cells. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2002;505:191–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5235-9_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dusza L, Ciereszko R, Skarzyński DJ, et al. Mechanism of phytoestrogens action in reproductive processes of mammals and birds. Reproductive Biology. 2006;6(supplement 1):151–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vedavanam K, Srijayanta S, O'Reilly J, Raman A, Wiseman H. Antioxidant action and potential antidiabetic properties of an isoflavonoid-containing soyabean phytochemical extract (SPE) Phytotherapy Research. 1999;13(7):601–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199911)13:7<601::aid-ptr550>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naderi GA, Asgary S, Sarraf-Zadegan N, Shirvany H. Anti-oxidant effect of flavonoids on the susceptibility of LDL oxidation. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;246(1-2):193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang X, Zhang C, Zeng W, Mi Y, Liu H. Proliferating effects of the flavonoids daidzein and quercetin on cultured chicken primordial germ cells through antioxidant action. Cell Biology International. 2006;30(5):445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boots AW, Li H, Schins RPF, et al. The quercetin paradox. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;222(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zava DT, Duwe G. Estrogenic and antiproliferative properties of genistein and other flavonoids in human breast cancer cells in vitro. Nutrition and Cancer. 1997;27(1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace JM. Nutritional and botanical modulation of the inflammatory cascade—eicosanoids, cyclooxygenases, and lipoxygenases—as an adjunct in cancer therapy. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2002;1(1):7–37. doi: 10.1177/153473540200100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson JK, Higo T, Hunter WL, Burt HM. The antioxidants curcumin and quercetin inhibit inflammatory processes associated with arthritis. Inflammation Research. 2006;55(4):168–175. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-0067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Z-P, Chen L-J, Fan L-Y, et al. Liposomal quercetin efficiently suppresses growth of solid tumors in murine models. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12(10):3193–3199. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graefe EU, Derendorf H, Veit M. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the flavonol quercetin in humans. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1999;37(5):219–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ader P, Wessmann A, Wolffram S. Bioavailability and metabolism of the flavonol quercetin in the pig. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2000;28(7):1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Woude H, ter Veld MGR, Jacobs N, van der Saag PT, Murk AJ, Rietjens IMCM. The stimulation of cell proliferation by quercetin is mediated by the estrogen receptor. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2005;49(8):763–771. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cappelletti V, Miodini P, Di Fronzo G, Daidone MG. Modulation of estrogen receptor-β isoforms by phytoestrogens in breast cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2006;28(5):1185–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J-D, Liu L, Guo W, Meydani M. Chemical structure of flavonols in relation to modulation of angiogenesis and immune-endothelial cell adhesion. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2006;17(3):165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamy S, Bédard V, Labbé D, et al. The dietary flavones apigenin and luteolin impair smooth muscle cell migration and VEGF expression through inhibition of PDGFR-β phosphorylation. Cancer Prevention Research. 2008;1(6):452–459. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh-Gupta V, Zhang H, Banerjee S, et al. Radiation-induced HIF-1α cell survival pathway is inhibited by soy isoflavones in prostate cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;124(7):1675–1684. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noonan DM, Benelli R, Albini A. Angiogenesis and cancer prevention: a vision. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 2007;174:219–224. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-37696-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sogno H, Vannini N, Lorusso G, et al. Anti-angiogenic activity of a novel class of chemopreventive compounds: oleanic acid terpenoids. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 2009;181:209–212. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69297-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulas V, Exarchou V, Troganis AN, et al. Phytochemicals in olive-leaf extracts and their antiproliferative activity against cancer and endothelial cells. Anti-angiogenic activity of a novel class of chemopreventive compounds: oleanic acid terpenoids. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2009;53:600–608. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan W, Lin L, Li M, et al. Quercetin, a dietary-derived flavonoid, possesses antiangiogenic potential. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;459(2-3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagar SM, Yance D, Wong RK. Natural health products that inhibit angiogenesis: a potential source for investigational new agents to treat cancer—part 2. Current Oncology. 2006;13(3):99–107. doi: 10.3747/co.v13i3.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kale R, Saraf M, Juvekar A, Tayade P. Decreased B16F10 melanoma growth and impaired tumour vascularization in BDF1 mice with quercetin-cyclodextrin binary system. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2006;58(10):1351–1358. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.10.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung H. Dietary quercetin inhibits proliferation of lung carcinoma cells. Forum of Nutrition. 2007;60:146–157. doi: 10.1159/000107165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanadaswami C, Lee L-T, Lee P-P, et al. The antitumor activities of flavonoids. In Vivo. 2005;19(5):895–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser HM. Regulation of the ovarian follicular vasculature. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2006;4, article 18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basini G, Grasselli F, Bianco F, Tirelli M, Tamanini C. Effect of reduced oxygen tension on reactive oxygen species production and activity of antioxidant enzymes in swine granulosa cells. BioFactors. 2004;20(2):61–69. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520200201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grasselli F, Baratta M, Tamanini C. Effects of a GnRH analogue (buserelin) infused via osmotic minipumps on pituitary and ovarian activity of prepubertal heifers. Animal Reproduction Science. 1993;32(3-4):153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benov L, Fridovich I. Is reduction of the sulfonated tetrazolium 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2-tetrazolium 5-carboxanilide a reliable measure of intracellular superoxide production? Analytical Biochemistry. 2002;310(2):186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ukeda H, Shimamura T, Tsubouchi M, Harada Y, Nakai Y, Sawamura M. Spectrophotometric assay of superoxide anion formed in Maillard reaction based on highly water-soluble tetrazolium salt. Analytical Sciences. 2002;18(10):1151–1154. doi: 10.2116/analsci.18.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barboni B, Turriani M, Galeati G, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor production in growing pig antral follicles. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;63(3):858–864. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiseman H. The bioavailability of non-nutrient plant factors: dietary flavonoids and phyto-oestrogens. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1999;58(1):139–146. doi: 10.1079/pns19990019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Ruvo C, Amodio R, Algeri S, et al. Nutritional antioxidants as antidegenerative agents. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2000;18(4-5):359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacey M, Bohday J, Fonseka SMR, Ullah AI, Whitehead SA. Dose-response effects of phytoestrogens on the activity and expression of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and aromatase in human granulosa-luteal cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2005;96(3-4):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelissero C, Lenczowski MJP, Chinzi D, Davail-Cuisset B, Sumpter JP, Fostier A. Effects of flavonoids on aromatase activity, an in vitro study. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1996;57(3-4):215–223. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice S, Mason HD, Whitehead SA. Phytoestrogens and their low dose combinations inhibit mRNA expression and activity of aromatase in human granulosa-luteal cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2006;101(4-5):216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krazeisen A, Breitling R, Möller G, Adamski J. Phytoestrogens inhibit human 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2001;171(1-2):151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitehead SA, Lacey M. Phytoestrogens inhibit aromatase but not 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) type 1 in human granulosa-luteal cells: evidence for FSH induction of 17β-HSD. Human Reproduction. 2003;18(3):487–494. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y-C, Nagpal ML, Stocco DM, Lin T. Effects of genistein, resveratrol, and quercetin on steroidogenesis and proliferation of MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;192(3):527–537. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Voorhis BJ, Dunn MS, Snyder GD, Weiner CP. Nitric oxide: an autocrine regulator of human granulosa-luteal cell steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 1994;135(5):1799–1806. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7525252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder GD, Holmes RW, Bates JN, Van Voorhis BJ. Nitric oxide inhibits aromatase activity: mechanisms of action. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1996;58(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masuda M, Kubota T, Aso T. Effects of nitric oxide on steroidogenesis in porcine granulosa cells during different stages of follicular development. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;144(3):303–308. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basini G, Tamanini C. Interrelationship between nitric oxide and prostaglandins in bovine granulosa cells. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2001;66(3):179–202. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(01)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grasselli F, Ponderato N, Basini G, Tamanini C. Nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide/cyclic GMP pathway in swine granulosa cells. Domestic Animal Endocrinology. 2001;20(4):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(01)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rüfer CE, Kulling SE. Antioxidant activity of isoflavones and their major metabolites using different in vitro assays. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(8):2926–2931. doi: 10.1021/jf053112o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vera R, Galisteo M, Villar IC, et al. Soy isoflavones improve endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats in an estrogen-independent manner: role of nitric-oxide synthase, superoxide, and cyclooxygenase metabolites. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2005;314(3):1300–1309. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milovanović V, Radulović N, Todorović Z, Stanković M, Stojanović G. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and genotoxicity screening of hydro-alcoholic extracts of five Serbian Equisetum species. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2007;62(3):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dufour C, Loonis M, Dangles O. Inhibition of the peroxidation of linoleic acid by the flavonoid quercetin within their complex with human serum albumin. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2007;43(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scandalios JG. Oxidative stress: molecular perception and transduction of signals triggering antioxidant gene defenses. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2005;38(7):995–1014. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Comporti M, Signorini C, Buonocore G, Ciccoli L. Iron release, oxidative stress and erythrocyte ageing. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2002;32(7):568–576. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong L, Chen FY, Wang HR, Ten Y, Wang C, Ouyang RR. Effects of quercetin on morphology and VEGF secretion of leukemia cells NB4 in vitro. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2006;28(1):25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasebe Y, Egawa K, Yamazaki Y, et al. Specific inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α activation and of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production by flavonoids. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2003;26(10):1379–1383. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin M-T, Yen M-L, Lin C-Y, Kuo M-L. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis by resveratrol through interruption of Src-dependent vascular endothelial cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;64(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bagli E, Stefaniotou M, Morbidelli L, et al. Luteolin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis; inhibition of endothelial cell survival and proliferation by targeting phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase activity. Cancer Research. 2004;64(21):7936–7946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tseng S-H, Lin S-M, Chen J-C, et al. Resveratrol suppresses the angiogenesis and tumor growth of gliomas in rats. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(6):2190–2202. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Igura K, Ohta T, Kuroda Y, Kaji K. Resveratrol and quercetin inhibit angiogenesis in vitro. Cancer Letters. 2001;171(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00443-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]