Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between the level of stromal surface irregularity after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and myofibroblast generation along with the development of corneal haze.

Variable levels of stromal surface irregularity were generated in rabbit corneas by positioning a fine mesh screen in the path of excimer laser during ablation for a variable percentage of the terminal pulses of the treatment for myopia that does not otherwise generate significant opacity. Ninety-six rabbits were divided into eight groups:

| Groups/Treatment | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII |

| PRK ablation | −4.5D | −4.5D | −4.5D | −4.5D | −4.5D | −9.0D | −9.0D | Unwounded |

| Indced irregularity SM; smoothing PTK |

– | 10% | 30% | 50% | 50%CSM | – | CSM | – |

Slit lamp analysis and haze grading were performed in all groups. Rabbits were sacrificed at 4 hr or 4 weeks after surgery and histochemical analysis was performed on corneas for apoptosis (TUNEL assay), myofibroblast marker alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and integrin α4 to delineate the epithelial basement membrane.

Slit-lamp grading revealed severe haze formation in corneas in groups IV and VI, with significantly less haze in groups II, III, and VII and insignificant haze compared with the unwounded control in groups I and V. Analysis of SMA staining at 4 weeks after surgery, the approximate peak of haze formation in rabbits, revealed low myofibroblast formation in group I (1.2 ± 0.2 cells/400× field) and group V (1.8 ± 0.4), with significantly more in groups II (3.5 ± 1.8), III (6.8 ± 1.6), VII (7.9 ± 3.8), IV (12.4 ± 4.2) and VI (14.6 ± 5.1). The screened groups were significantly different from each other (p <0.05), with myofibroblast generation increasing with higher surface irregularity in the −4.5 diopter PRK groups. The −9.0 diopter PRK group VI had significantly more myofibroblast generation than the −9.0 diopter PRK with PTK-smoothing group VII (p <0.01). Areas of basement membrane disruption were demonstrated by staining corneas for integrin α4 and were prominent in corneas with grade I or higher haze. SMA-positive myofibroblasts tended to be present sub-adjacent to basement membrane defects. Late apoptosis was detected at 1 month after surgery within clusters of myofibroblasts in the sub-epithelial stroma.

In conclusion, these results demonstrated a relationship between the level of corneal haze formation after PRK and the level of stromal surface irregularity. PTK-smoothing with methylcellulose was an effective method to reduce stromal surface irregularity and decreased both haze and associated myofibroblast density. We hypothesize that stromal surface irregularity after PRK for high myopia results in defective basement membrane regeneration and increased epithelium-derived TGFβ signalling to the stroma that increases myofibroblast generation. Late apoptosis appears to have a role in the disappearance of myofibroblasts and haze over time.

Keywords: cornea, myofibroblast, haze, irregularity, PRK, stroma, wound healing

1. Introduction

The corneal wound healing process following corneal refractive procedures involves a very complex and sometimes unpredictable biological response. After photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), the organization of the extracellular matrix is altered in the anterior stroma, and along with changes in cellular density and phenotype, can be associated with the production of disorganized extracellular matrix components. The final result is a decrease in tissue transparency-referred to as corneal haze or opacity. In most patients the level of stromal opacity that develops following PRK is not clinically significant, but in some, especially with higher levels of correction, the opacity can be severe. The generation of corneal myofibroblast cells has recently been identified as the primary biological event responsible for the formation of corneal haze (Jester et al., 1999a, 2003; Maltseva et al., 2001). Myofibroblasts are highly contractile cells with reduced transparency attributable to decreased intracellular crystallin production (Jester et al., 1999b).

Several factors have been suggested to contribute to haze formation after PRK, including the length of time required for epithelial defect healing, the depth of the ablation, irregularity of the postoperative stromal surface, removal of the epithelial basement membrane, or ablation of Bowman’s layer (Tang and Liao, 1997; Vinciguerra et al., 1998a,b; Moller-Pedersen et al., 1998; Nakamura et al., 2001; Serrao et al., 2003; Stramer et al., 2003; Kuo et al., 2004). There, however, has been no conclusive evidence supporting any particular hypothesis.

One of the most intriguing aspects of haze formation is that it rarely occurs in eyes that have lower levels of myopia corrected with PRK, even though the procedure is otherwise identical. Thus, eyes that have PRK for less than six diopters of myopia rarely develop significant haze. As the level of correction increases beyond six diopters, however, the incidence of clinically significant haze increases to as high as 2–4% (Lipshitz et al., 1997; Hersh et al., 1997; Shah et al., 1998; Siganos et al., 1999). Studies of PRK in rabbits confirmed that there was also a relationship between the level of correction and haze and myofibroblast formation in this model (Mohan et al., 2003). Any hypothesis proposed to account for haze formation should incorporate this clinical observation.

It has long been noted that abnormalities associated with surface irregularity abnormalities, such as topographic central islands and peninsulas, increase with increasing levels of correction after PRK. Vinciguerra et al. (1998a,b) reported a clinical correlation between the irregularity of the ablated surface after PRK and the incidence of corneal haze in a group of eighty eyes and noted a decrease in the incidence of haze when PRK included a stromal PTK-smoothing procedure. Taylor et al. (1994) performed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in rabbit corneas that had different levels of excimer laser ablation and showed that there was an increase in irregularity of the ablated surface as the depth of the ablation increased. More recently, Horgan et al. (1999) demonstrated with SEM that phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) could be used to reduce stromal irregularity after PRK in porcine corneas. A lower incidence of corneal haze was also noted after PRK followed by PTK-smoothing by Serrao et al. (2003) in a ten-patient contralateral-eye study.

The present study tested the hypothesis that corneal haze and myofibroblast generation are related to the level of stromal surface irregularity after PRK using a rabbit model in which reproducible levels of surface irregularity were generated. The effect of PTK-smoothing on myofibroblast generation was also examined. Finally, the effect of surface irregularity after PRK on basement membrane regeneration was also explored.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and surgery

The Animal Control Committee at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation approved all of the animal studies included in this work. All animals were treated in accordance with the tenets of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Anaesthesia was achieved by intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (30 mg kg−1) and xylazine hydrochloride (5 mg kg−1). In addition, topical proparacaine hydrochloride 1% (Alcon, Ft. Worth, TX, USA) was applied to each eye just before surgery. Euthanasia was performed with an intravenous injection of 100 mg kg−1 pentobarbital while the animal was under general anaesthesia.

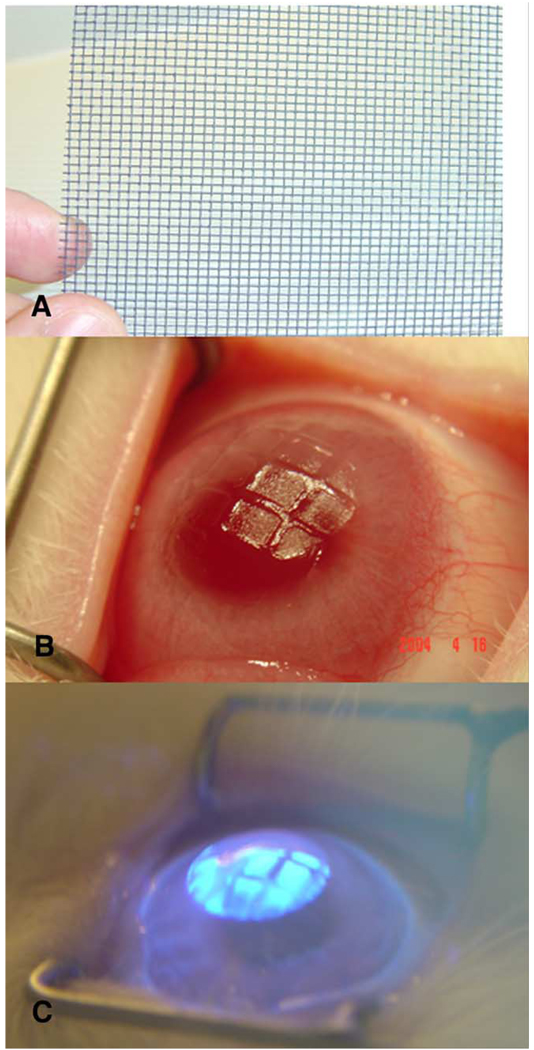

A total of ninety-six 12- to 15-week-old female New Zealand white rabbits weighing 2.5–3.0 kg each were included in this study. One eye of each rabbit, selected at random, had PRK with a 6.0 mm ablation zone using an Apex Summit Laser (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA). Eight groups were included, as shown in Table 1: (I) −4.5 diopter PRK, (II) −4.5 diopter PRK with a metallic screen mesh inserted in the path of excimer laser ablation (Fig. 1A and B) for the final 10% of excimer laser pulses, (III) −4.5 diopter PRK with screening of the final 30% of excimer laser pulses, (IV) −4.5 diopter PRK with screening of the final 50% of excimer laser pulses, (V) −4.5 diopter PRK with screening of the final 50% of PRK pulses followed by phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK)-smoothing, (VI) −9.0 diopter PRK for high myopia (as a positive control for myofibroblast generation and haze, Mohan et al., 2003), (VII) −9.0 diopter PRK followed by PTK-smoothing, and (VIII) unwounded control corneas. In preliminary experiments we noted no difference between metal and plastic screens with openings of the same size.

Table 1.

Treatment groups for rabbit eyes

| Group | Number of eyes per time point (n) |

PRK correction in diopters (number of unimpeded pulses) |

Percentage irregularity (number of pulses delivered through screen) |

Number of PTK-smoothing pulses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 6 | −4.5 D (237 pulses) | – | – |

| II | 6 | −4.5 D (213 pulses) | 10% (24 pulses) | – |

| III | 6 | −4.5 D (165 pulses) | 30% (72 pulses) | – |

| IV | 6 | −4.5 D (117 pulses) | 50% (120 pulses) | – |

| V | 6 | −4.5 D (117 pulses) | 50% (120 pulses) | 150 pulses |

| VI | 6 | −9.0 D (421 pulses) | – | – |

| VII | 6 | −9.0 D (421 pulses) | – | 150 pulses |

| VIII | 6 | – | – | – |

Fig. 1.

(A) Metallic screen used to induce corneal irregularity. (B) Profile view of a rabbit cornea showing induced irregularity in an eye with −4.5 diopter PRK with 50% of the ablation over the metallic screen. (C) PTK-smoothing technique with excimer laser ablating elevations, but the valleys masked from laser pulses by methylcellulose solution.

Two time points (4 hr and 4 weeks after surgery) were examined in each of the eight groups with six eyes at each time point. These time points were selected on the basis of previous studies of PRK in rabbits (Mohan et al., 2003) that demonstrated that 4 hr was the approximate peak for keratocyte apoptosis and 4 weeks was the approximate peak for haze and myofibroblast generation.

With the animal under general and local anaesthesia, a wire lid speculum was positioned within the interpalpebral fissure and a 7 mm-diameter area of epithelium overlying the pupil was removed by scraping with a #64 blade (Beaver; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA). A spherical laser ablation was performed with the Summit Apex excimer laser (Alcon, Ft. Worth, TX) with a 6.0 mm-diameter optical zone. The −4.5 diopter ablation had a programmed depth of 54 µm (237 pulses) and the −9.0 diopter ablation had a programmed depth of 108 µm (421 pulses). The ablation was stopped at the specified point during the ablation in groups II–V and the metallic screen placed over the ablation for the remaining pulses. PTK-smoothing of induced surface irregularity in group V or following −9.0 diopter PRK in group VII was performed using a previously described method (Vinciguerra et al., 1998) with 1% methylcellulose diluted 1:5 in phosphate buffered saline as the masking agent and 150 pulses of the 6.0 mm excimer laser ablation beam to completely smooth the surface irregularity (Fig. 1C). Two drops of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 0.3% (Ciloxan, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) were instilled into the eye at the end of the procedure. Any eye that developed infiltration suggestive of infection or an epithelial defect persisting beyond 1 week after surgery was excluded from the study and an additional animal was substituted in its place.

2.2. Biomicroscopic grading of corneal haze

Animals were evaluated at the slit-lamp (Haag-Streit BM900, Haag-Streit, Switzerland) while under general anaesthesia by a trained cornea specialist (MVN). Animals were not masked. Corneal haze was graded according to the system reported by Fantes et al. (1990): grade 0 for a completely clear cornea; grade 0.5 for trace haze seen with careful oblique illumination with slit-lamp biomicroscopy; grade 1 for more prominent haze not interfering with visibility of fine iris details; grade 2 for mild obscuration of iris details; grade 3 for moderate obscuration of the iris and lens; and grade 4 for completely opacification of the stroma in the area of the ablation.

2.3. Cornea collection, fixation and sectioning

Rabbits were euthanized and the corneoscleral rims of ablated and unablated contralateral control eyes were removed with 0.12 forceps and sharp Westcott scissors. For histological analyses, the corneas were embedded in liquid OCT compound (Sakura FineTek, Torrance, CA, USA) within a 24 mm×24 mm×5 mm mould (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Cornea specimens were centred within the mould so that the block could be bisected and transverse sections cut from the centre of the cornea. The mould and tissue were rapidly frozen in 2-methyl butane within a stainless steel crucible suspended in liquid nitrogen. The frozen tissue blocks were stored at −85 °C until sectioning was performed. Central corneal sections (7 µm thick) were cut with a cryostat (HM 505M, Micron GmbH, Walldorf, Germany). Sections were placed on 25 mm×75 mm×1 mm microscope slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher) and maintained frozen at −85 °C until staining was performed.

2.4. TUNEL assay and immunohistochemistry assays

To detect fragmentation of DNA associated with keratocyte apoptosis (Helena et al., 1998), tissue sections were fixed in acetone at −20 °C for 2 min, dried at room temperature for 5 min, and then placed in balanced salt solution. A fluorescence-based TUNEL assay was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ApopTag, Cat No; S7165; Intergen, Purchase, NY, USA). Positive (4 hr after mechanical corneal scrape) and negative (unwounded) control slides were included in each assay. Photographs were obtained with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon E600, Melville, NY, USA).

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously published (Zieske and Wasson, 1993). The monoclonal antibody for anti-integrin β4 (Serotec, UK) or anti-SMA (DAKO; Carpinteria, CA, USA), a marker for myofibroblasts, was placed on the sections and incubated at room temperature for either 2 hr (anti-integrin β4) or 1 hr (anti-SMA). The working concentrations for anti-integrin beta-4 and anti-SMA were 214.6 mg l−1 (1% BSA, pH 7.4) and 85 mg l−1 (1% BSA), respectively. The secondary antibody, fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch; West Grove, PA, USA), was applied for 1 hr at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc.; Burlingame, CA, USA) to allow visualization of all nuclei in the tissue sections. Negative controls were included with irrelevant isotype-matched antibodies and secondary antibody alone. The sections were viewed and photographed with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a digital SPOT camera (Micro Video Instruments; Avon, MA, USA).

2.5. Cell counting for quantification of TUNEL assays and immunohistochemistry assays

Six corneas with each surgical procedure were used for counting at each time point. In each cornea, all of the cells in seven non-overlapping, full-thickness columns extending from the anterior stromal surface to the posterior stromal surface were counted. The diameter of each column was a 400× microscope field. The columns in which counts were performed were selected at random from the central cornea of each specimen.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using statistical software (Statview 4.5, Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). Variance was expressed as the standard error of the mean (sem). Statistical comparisons between the groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferonni-Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical tests were conducted at an alpha level of 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Corneal haze evaluated by biomicroscopy

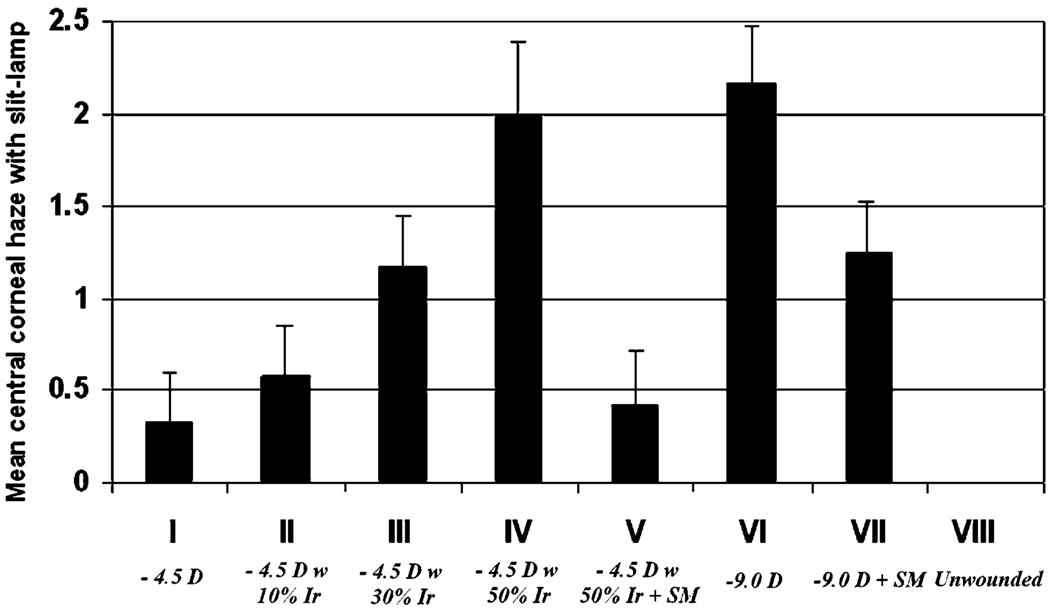

Corneal haze was noted beginning at 2 weeks and appeared to peak around 4 weeks after surgery in all groups. The quantitative assessment of haze was significantly greater in the PRK for −9.0 diopters of myopia group VI than in the PRK for −4.5 diopters of myopia group I. When stromal surface irregularity was induced in the −4.5 diopter PRK groups, a marked increase in haze was observed at 4 weeks (Table 2 and Table 3; Fig. 2), with the increase in corneal haze formation being directly related to the level of induced irregularity. When PTK smoothing was performed after PRK for −4.5 diopters of myopia with 50% induced irregularity (group V) significantly less corneal haze resulted at 4 weeks after surgery (Table 2 and Table 3). Similarly, compared with PRK for −9.0 diopters of myopia (group VI), the PRK for −9.0 diopters of myopia followed by PTK smoothing (group VII) had significantly less haze at 4 weeks after surgery (p <0.01; Table 3; Fig. 2). It is important to note that in the rabbit PTK-smoothing did not completely reduced haze in corneas that had−9.0 diopter PRK (Fig. 2; Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Corneal haze grading (biomicroscopic analysis) at 4 wee−s after surgery.

| Groups | Group I −4.5D |

Group II −4.5D+10% Irr |

Group III −4.5D+30% Irr |

Group IV −4.5D+50% Irr |

Group V −4.5D+50% Irr +SM |

Group VI −9.0D | Group VII −9.0D+SM |

Group VIII Unwound control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Grade 0.5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Grade 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Grade 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Grade 3 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Grade 4 | ||||||||

| Mean haze | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0 |

| SD | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0 |

Irr, induced irregularity; SM, PTK-smoothing.

Table 3.

Haze with biomicroscopy statistics

| Groups | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| II | 0.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| III | <0.001 | 0.007 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| IV | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | – | – | – | – |

| V | 0.60 | 0.16 | 0.001 | <0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| VI | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.55 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| VII | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.33 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | – |

| VIII | 0.30 | 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – |

Fig. 2.

Quantitation of central corneal haze monitored at the slit lamp at 4 weeks after surgery in the different groups. Error bars represent sd.

3.2. Stromal myofibroblast cells

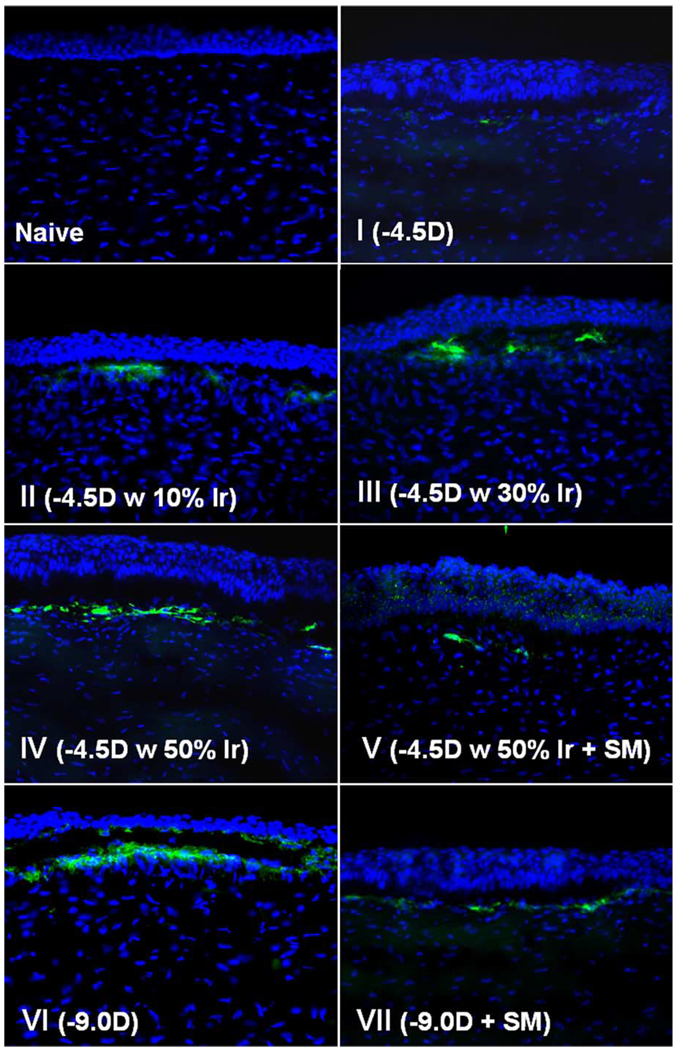

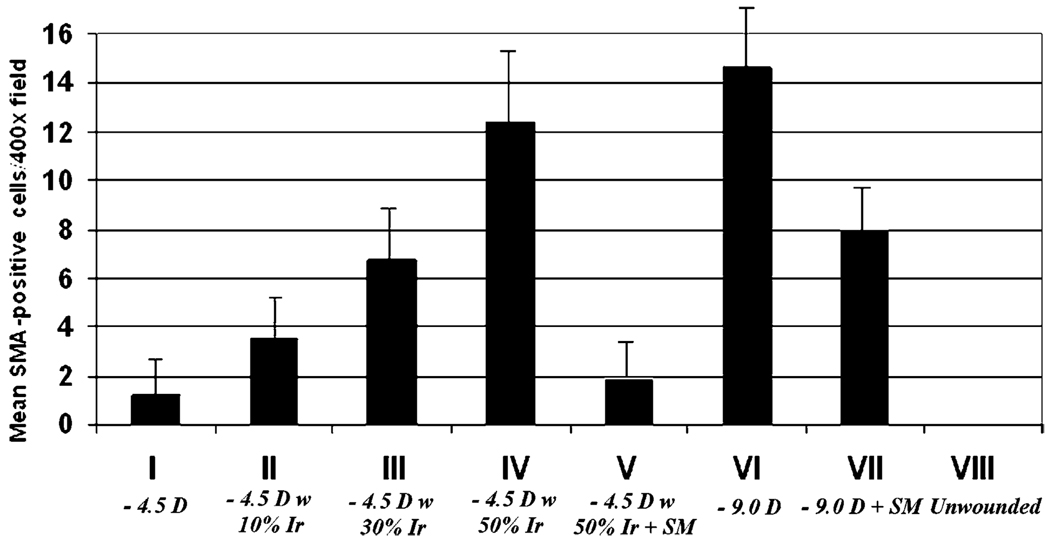

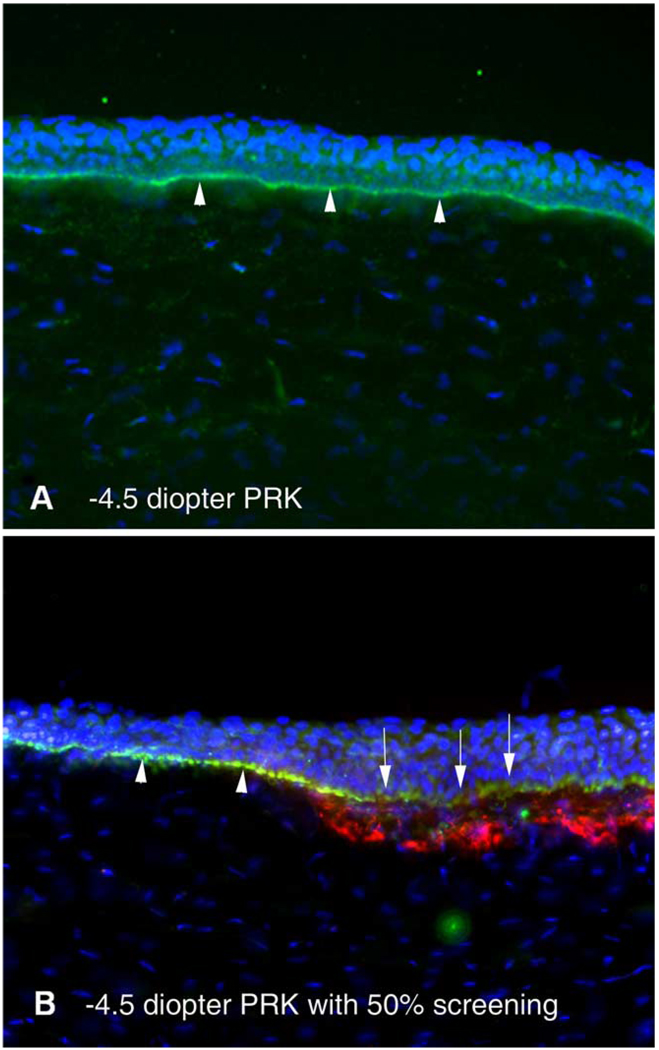

Myofibroblast cell density also correlated with surface irregularity (Fig. 3 and Fig 4; Table 4). α-smooth muscle actin staining was not detected in any group at the 4-hr postoperative time point. At 4 weeks after surgery, the time point at which haze peaked in this study and myofibroblasts peaked in prior studies (Mohan et al., 2003), anti-α-smooth muscle actin expressing cells were present in the anterior stroma just below the epithelium in all groups except the unwounded control group (Fig. 3 and Fig 4). However, neither the −4.5 diopter PRK group nor the −4.5 diopter PRK with 50% irregularity followed by PTK smoothing were significantly different from the unwounded control group. The other groups were significantly different from the unwounded control group, and in some cases from each other (Fig. 4; Table 4). Thus, α-smooth muscle actin expressing cells were present at the highest density in the anterior stroma of corneas in the −9.0 diopter PRK group VI, but when surface irregularity was induced in the −4.5 diopter PRK groups II–IV, the density of α-smooth muscle actin-expressing cells increased as the level of induced surface irregularity increased. There was a significant decrease in the density of α-smooth muscle actin-expressing myofibroblasts in the stroma when PTK smoothing was performed after −9.0 diopter PRK (group VII) or −4.5 diopter PRK with 50% irregularity (group V) compared to the corresponding groups without PTK-smoothing (Fig. 3 and Fig 4).

Fig. 3.

Alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining of the central corneas from eyes of rabbits in groups I–VII and naïve unwounded control (group VIII) at 4 weeks after surgery. Cells nuclei are stained blue with DAPI and SMA-positive cells are stained green. Magnification 400×. (For interpretation of the reference to colour in this legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

Fig. 4.

Quantitation of α-smooth muscle actin-positive central corneal stromal cells/400× microscope field positioned so they are bisected by basement membrane at 4 weeks after laser surgery in all treatment groups error bars represent sd.

Table 4.

Alpha smooth muscle actin-positive cell statistics

| Groups | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| II | 0.007 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| III | <0.001 | 0.003 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| IV | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | – | – | – | – | – |

| V | 0.150 | 0.035 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| VI | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.212 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| VII | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.570 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.001 | – | – |

| VIII | 0.012 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – |

3.3. Epithelial basement membrane disruption

Staining for integrin β4 demonstrated removal of the epithelial basement membrane within the excimer laser photo-ablated area of all groups at 4 hr after surgery (not shown). Significant regeneration of the basement membrane was observed by 4 weeks in all groups that had surgery. Residual disruptions of the basement membrane (Fig. 5) were frequently noted in the −9.0 diopter PRK group VI and all −4.5 diopter PRK groups with induced irregularity (II–IV) in eyes that had grade 1 or greater haze at 4 weeks after surgery. No difference in the level of basement membrane disruption was noted between eyes with grade I, II, or III haze. Although we found no method to reliably quantitate these basement membrane disruptions, they appeared be much less common in the groups that had PTK-smoothing (groups V and VII) compared to the corresponding groups without PTK-smoothing (groups IV and VI, respectively). Importantly, these disruptions were frequently associated with underlying α-smooth muscle actin expressing myofibroblasts (Fig. 5). In contrast, α-smooth muscle actin-expressing myofibroblasts were rarely observed in the corneas of any groups in areas where the basement membrane appeared to be intact.

Fig. 5.

Basement membrane defects and myofibroblasts in corneas with irregular surfaces after PRK. Triple staining of the central cornea for α-smooth muscle actin-expressing myofibroblasts (red) and integrin beta-4 (green), along with DAPI (blue). (A) Note the homogeneous basement membrane regeneration (arrowheads) in a cornea from group I without haze after −4.5 diopter PRK. (B) Basement membrane with obvious disruptions (arrows) adjacent to an area with more uniform basement membrane (arrowheads) after −4.5 diopter PRK with 50% screening of the pulses (group IV). Similar disruptions were noted in corneas that had −9 diopter PRK without screening of pulses (group VI, not shown). Red α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells can be noted below the defects in the basement membrane. Magnification 400×. (For interpretation of the reference to colour in this legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.4. Apoptotic cells in the corneal stroma

TUNEL-positive cells were detected in the anterior stroma at 4 hr in all groups except the unwounded control group. More TUNEL-positive cells were detected in the −9.0 diopter PRK for myopia group VI than in the−4.5 diopter PRK for myopia group I (p <0.01 at 4 hr after surgery (47 ± 6 and 32 ± 5, respectively). However, there was no correlation between the density of TUNEL-positive cells at 4 hr after surgery and haze at 4 weeks after surgery or the density of α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells at 4 weeks after surgery (not shown).

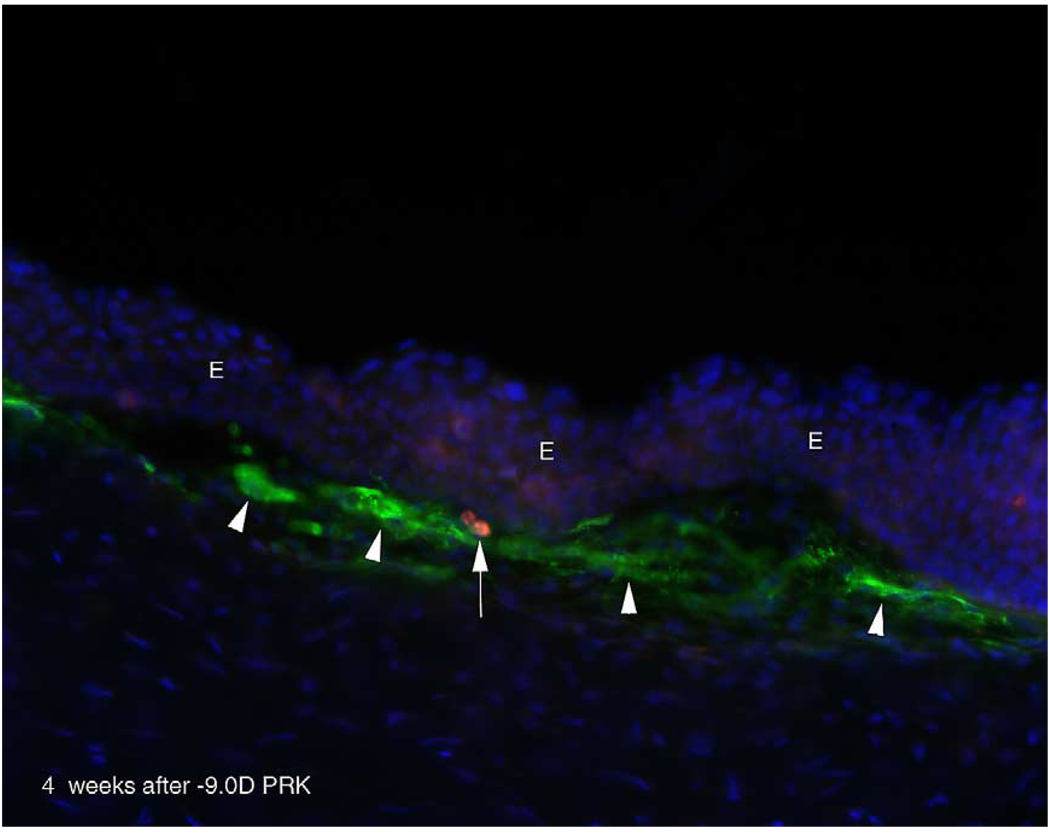

Occasional TUNEL-positive cell were seen in the anterior stroma at 4 weeks after surgery in some tissue sections of all groups with haze that were double-stained for α-smooth muscle actin and TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 6). Such cells were rare, even in the −9.0 diopter PRK group VI where they were most commonly noted. When these cells were seen, they were usually located in the sub-epithelial stroma. We estimated that one of these TUNEL-positive cells was noted in one out of twenty to thirty sections from corneas in the −9.0 diopter PRK group when serial sections were examined.

Fig. 6.

Apoptosis in the myofibroblast cell layer at 1 month after PRK. Triple staining for α-smooth muscle actin-expressing myofibroblasts (green), TUNEL-positive cells (red), and DAPI for cell nuclei (blue). Myofibroblasts (arrowheads) beneath the epithelium (E) in a cornea at 4 weeks after −9 diopter PRK. A cell (arrow) in the stroma within the fibrous layer with myofibroblasts is undergoing apoptosis. Magnification 400×. (For interpretation of the reference to colour in this legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that there is a relationship between the level of corneal haze formation after PRK, and associated anterior stromal myofibroblasts, and the level of stromal surface irregularity remaining after surface ablation. In corneas with surface irregularity, there also appear to be defects in the basement membrane after healing of the epithelium and these defects appear to correspond to areas where myofibroblasts are generated in the anterior stroma. In addition, our findings suggest that late apoptosis may have a role in the disappearance of myofibroblasts and haze over time.

Stromal scarring or haze (the clinical name for opacity) is a serious problem following corneal surgery or injury. For example, clinically significant corneal haze has been noted in 2–4% or more of eyes after excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), depending on the level of attempted correction (Lipshitz et al., 1997; Hersh et al., 1997; Shah et al., 1998; Siganos et al., 1999; Kuo et al., 2004). The incidence of haze after PRK in humans increases with increasing attempted correction (Kuo et al., 2004) and increasing volume of stromal tissue removal (Moller-Pedersen et al., 1998). A study in rabbits demonstrated that this same relationship holds-eyes treated with −9.0 diopter PRK for myopia developed marked haze and those treated with −4.5 diopter PRK for myopia developed little, if any, haze (Mohan et al., 2003). Haze after surface ablation continues to be a problem after surgery with small spot scanning lasers, especially with higher levels of correction.

Myofibroblasts are thought to be major contributors to the development of corneal opacity. Jester et al. (1999c) demonstrated that myofibroblasts, compared to keratocytes, express decreased levels of corneal crystallins that are at least partially responsible for the tissue transparency. When severe haze develops in human corneas after PRK, it is nearly always localized immediately beneath the epithelium in the anterior stroma (Shah et al., 1998; Siganos et al., 1999)—in the same location that myofibroblasts are noted in rabbit eyes that develop haze after −9.0 diopter PRK for myopia (Mohan et al., 2003). This localization, and the absence of myofibroblasts in the central cornea of rabbit eyes that had−9.0 diopter laser in situ keratomilieusis (LASIK) for myopia, suggested that interactions between the stroma and epithelium were critical in the development of haze. Evidence for the importance of epithelial signals in generating haze was obtained from experiments in rabbits, in which myofibroblasts were generated anterior and posterior to a lamellar cut containing ectopic epithelium (Wilson et al., 2003). Stramer et al. (2003) also demonstrated a critical role for epithelium in the appearance of myofibroblasts in the corneal stroma.

Previous clinical reports (Vinciguerra et al., 1998a,b; Serrao et al., 2003) have suggested a correlation between stromal surface irregularity and corneal haze formation in PRK. The current study in rabbits also suggests that PRK-smoothing reduces haze after PRK and demonstrates conclusively that haze and myofibroblast density increase as surface irregularity is artificially increased, even after −4.5 diopter PRK for myopia where little or no haze or myofibroblasts are typically noted. The data also demonstrate that PTK-smoothing reduces haze and myofibroblast density after either −4.5 diopter PRK for myopia with induced irregularity or −9.0 diopter PRK in rabbit corneas. Importantly, haze is not reduced to baseline levels by PTK-smoothing after −9.0 diopter PRK (group VII), suggesting that there are also other factors involved in the development of haze. These other factors could not be detected by the current study, but could relate to tissue volume removed (Moller-Pedersen et al., 1998), differences in keratocyte phenotype between the anterior and posterior stroma (Mohan et al., 2003), differences in nerve regeneration with higher compared to lower PRK treatments (Linna et al., 2000), or other unknown factors.

The data in this study also provide preliminary evidence that defective regeneration of basement membrane may be a key factor in the development of haze and increased myofibroblast density in corneas with surface irregularity. Thus, ultrastructural defects in the basement membrane were noted in eyes with grade I or greater haze and myofibroblasts were commonly noted beneath disruptions in regenerated basement membrane detected using immunohistochemical staining for integrin β4 (Fig. 5). Studies reported by Strammer et al. (2003) previously suggested the important role played by intact basement membrane in determining the regenerative versus the fibrotic character of corneal repair. Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) is known to have a critical role in myofibroblast generation (Masur et al., 1996; Jester et al., 1999a,b; Maltseva et al., 2001). We hypothesize that TGFβ, and perhaps other cytokines derived from the overlying epithelium, penetrate into the stroma at increased levels when there are defects (ultrastructural or functional) in the basement membrane and thereby modulate myofibroblast generation from progenitor cells. Further studies are needed to confirm the specific mechanisms through which the basement membrane modulates wound healing.

Haze tends to peak at 6–9 months after PRK in humans and then gradually diminishes over time—taking years to resolve in some patients (Wilson, unpublished data, 1998; Kuo et al., 2004). Mohan et al. (2003) noted that the peak in haze tends to occur at approximately 1 month after PRK in rabbits, but also diminishes over the subsequent months. Maltseva et al. (2001) based on in vitro studies, suggested that fibroblast growth factor plays an important role in myofibroblast trans-differentiation back to the progenitor cell. However, Mohan et al. (2003) noted apoptotic cells that appeared to coincide with myofibroblasts at 1 and 3 months after −9.0 diopter PRK. Similar apoptotic anterior stromal cells were noted in this study in some corneas that had haze, especially after either −4.5 diopter PRK with marked surface irregularity (group III or IV) or −9.0 diopter PRK (group VI). It is important to note that this apoptosis would likely be an exceedingly rare event, considering the many months required for haze to disappear completely. We hypothesize that the basement membrane defects noted after PRK in this study are repaired over time, even in corneas with marked surface irregularity, and that this repair results in a decrease in epithelium-derived TGFβ penetration into the stroma that in turn leads to myofibroblast apoptosis and associated clearing of haze. Disappearance of haze would likely be mediated not only by a decrease in myofibroblast density, via apoptosis and/or trans-differentiation, but also by reabsorbtion and/or reorganization of disorganized matrix materials, including collagen, by keratocytes.

Undoubtedly many aspects of the corneal wound healing response differ quantitatively between the human and the rabbit model used in this study. Thus, essentially 100% of rabbit eyes that have −9.0 diopter PRK (group VI) develop severe subepithelial opacity, whereas only 2–4% of human eyes develop severe subepithelial opacity after similar levels of PRK (Lipshitz et al., 1997; Hersh et al., 1997). However, in studies performed in human eyes enucleated to treat tumours the pattern of the wound healing response in humans is very similar to that in rabbits (Ambrósio Jr., R., et al., 2002 Early wound healing response to epithelial scrape injury in the human cornea. ARVO Annual Meeting, Program No. 4206). Thus, the rabbit provides a useful model for studying disorders of wound healing that occur in some patients after refractive surgery procedures like PRK. We cannot exclude the possibility that inserting a plastic or metal mesh in the excimer laser beam somehow insights inflammation or otherwise alters the healing response, although no difference in inflammatory cell infiltration was noted in sections evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated conclusively that there are relationships between surface irregularity, haze, and myofibroblasts generation after PRK in the rabbit. It also suggests that defective basement membrane regeneration has an important role in the development of haze and generation of myofibroblasts in the cornea.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by US Public Health Service grants EY 10056 and EY 15638 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

References

- Fantes FE, Hanna KD, Waring GO, Pouliquen Y, Thompson KP, Savoldelli M. Wound healing after excimer laser keratomileusis (photorefractive keratectomy) in monkeys. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1990;108:665–675. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070070051034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helena MC, Baerveldt F, Kim WJ, Wilson SE. Keratocyte apoptosis after corneal surgery. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh PS, Stulting RD, Steinert RF, Waring GO, III, Thompson KP, O’Connell M, Doney K, Schein OD The summit PRK study group. Results of phase III excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy for myopia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1535–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan SE, McLaughlin-Borlace L, Stevens JD, Munro PM. Phototherapeutic smoothing as an adjunct to photorefractive keratectomy in porcine corneas. J. Refract. Surg. 1999;15:331–333. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19990501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Ho-Chang J. Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractility and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;77:581–592. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Huang J, Barry-Lane PA, Kao WW, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD. Transforming growth factor (beta)-mediated corneal myofibroblast differentiation requires actin and fibronectin assembly. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999a;40:1959–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD. Corneal stromal wound healing in refractive surgery: the role of myofibroblasts. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999b;18:311–356. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Moller-Pedersen T, Huang J, Sax CM, Kays WT, Cavangh HD, Petroll WM, Piatigorsky J. The cellular basis of corneal transparency: evidence for ‘corneal crystallins’. J. Cell Sci. 1999c;112:613–622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo IC, Lee SM, Hwang DG. Late-onset corneal haze and myopic regression after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) Cornea. 2004;23:350–355. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linna TU, Vesaluoma MH, Perez-Santonja JJ, Petroll WM, Alio JL, Tervo TM. Effect of myopic LASIK on corneal sensitivity and morphology of subbasal nerves. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41;2000:393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz I, Loewenstein A, Varssano D, Lazar M. Late onset corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy for moderate and high myopia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:369–373. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva O, Folger P, Zekaria D, Petridou S, Masur SK. Fibroblast growth factor reversal of the corneal myofibroblast phenotype. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:2490–2495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur S, Dewal HS, Dinh TT, Erenburg I, Petridou v. Myofibroblasts differentiate from fibroblasts when plated at low density. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:4219–4223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan RR, Hutcheon AE, Choi R, Hong J, Lee J, Mohan RR, Ambrosio R, Jr, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Apoptosis, necrosis, proliferation, and myofibroblast generation in the stroma following LASIK and PRK. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;76:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Pedersen T, Cavanagh HD, Petroll WM, Jester JV. Corneal haze development after PRK is regulated by volume of stromal tissue removal. Cornea. 1998;17:627–639. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): role in corneal wound healing and homeostasis. Exp. Eye Res. 2001;72:511–517. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrao S, Lombardo M, Mondini F. Photorefractive keratectomy with and without smoothing: a bilateral study. J. Refract. Surg. 2003;19:58–64. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030101-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SS, Kapadia MS, Meisler DM, Wilson SE. Photorefractive keratectomy using the summit SVS Apex laser with or without astigmatic keratotomy. Cornea. 1998;17:508–516. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siganos DS, Katsanevaki VJ, Pallikaris IG. Correlation of subepithelial haze and refractive regression 1 month after photorefractive keratectomy for myopia. J. Refract. Surg. 1999;15:338–342. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19990501-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stramer BM, Zieske JD, Jung JC, Austin JS, Fini ME. Molecular mechanisms controlling the fibrotic repair phenotype in cornea: implications for surgical outcomes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:4237–4246. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Liao Z. A clinical study of correlation between ablation depth and corneal subepithelial haze after photorefractive keratectomy. Zhonghua. Yan. Ke. Za. Zhi. 1997;33:204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Fields CR, Barker FM, SanzoC J. Effect of depth upon the smoothness of excimer laser corneal ablation. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1994;71:104–108. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra P, Azzolini M, Airaghi P, Radice P, De Molfetta V. Effect of decreasing surface and interface irregularities after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis on optical and functional outcomes. J. Refract. Surg. 1998a;14:S199–S203. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19980401-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra P, Azzolini M, Radice P, Sborgia M, De Molfetta V. A method for examining surface and interface irregularities after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis: predictor of optical and functional outcomes. J. Refract. Surg. 1998b;14:S204–S206. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19980401-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Hutcheon AEK, Mohan RR, Ambrósio R, Zieske JD, Hong JW, Lee J-S. Effect of ectopic epithelial tissue within the stroma on keratocyte apoptosis, mitosis, and myofibroblast transformation. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;76:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Wasson M. Regional variation in distribution of EGF receptor in developing and adult corneal epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:145–152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]