Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of changing to travoprost BAK-free from prior prostaglandin therapy in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension.

Design

Prospective, multi-center, historical control study.

Methods

Patients treated with latanoprost or bimatoprost who needed alternative therapy due to tolerability issues were enrolled. Patients were surveyed using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) to evaluate OSD symptoms prior to changing to travoprost BAK-free dosed once every evening. Patients were re-evaluated 3 months later.

Results

In 691 patients, travoprost BAK-free demonstrated improved mean OSDI scores compared to either latanoprost or bimatoprost (p < 0.0001). Patients having any baseline OSD symptoms (n = 235) demonstrated significant improvement after switching to travoprost BAK-free (p < 0.0001). In 70.2% of these patients, symptoms were reduced in severity by at least 1 level. After changing medications to travoprost BAK-free, mean intraocular pressure (IOP) was significantly decreased (p < 0.0001). Overall, 72.4% preferred travoprost BAK-free (p < 0.0001, travoprost BAK-free vs prior therapy). Travoprost BAK-free demonstrated less conjunctival hyperemia than either prior therapy (p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Patients previously treated with a BAK-preserved prostaglandin analog who are changed to travoprost BAK-free have clinically and statistically significant improvement in their OSD symptoms, decreased hyperemia, and equal or better IOP control.

Keywords: glaucoma, prostaglandin analog, travoprost, latanoprost, bimatoprost, preservative, benzalkonium chloride, ocular surface disease

Introduction

Symptoms of dry eye are reported in approximately 15% of the elderly according to a population-based study conducted by Schein et al (1997). However, it has recently been reported by Fechtner et al (2008) that prevalence of ocular surface disease (OSD) symptoms in glaucoma patients is 48.4% and the severity of OSD symptoms increases with the number of medications used. This increased occurrence of dry eye symptoms in glaucoma patients is of particular interest. Glaucoma patients may be at an increased risk of developing dry eye symptoms due to the long-term use of intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering medications. Many of these medications contain preservatives which have been associated with an increase in the prevalence of ocular signs and symptoms (Kuppens et al 1995; Pisella et al 2002; Jaenen et al 2007). Benzalkonium chloride (BAK), the most commonly used preservative in ophthalmic preparations, has a high affinity for membrane proteins and may accumulate in ocular tissues, inducing cell toxicity and/or cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Yee 2007).

Introduced in 1996, the prostaglandin analog class of IOP-lowering medications has become the most common first-line therapy for the treatment of elevated IOP in the US generally because of its efficacy and systemic tolerability. However, prostaglandin analog preparations have traditionally been preserved with BAK and have been shown to damage ocular tissue by inducing apoptosis and increasing the concentrations of inflammatory markers (Noecker et al 2004; Baudouin et al 2007).

Travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution (TRAVATAN Z®, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) was recently introduced as the first commercially available preparation of a prostaglandin analog preserved without BAK. Travoprost BAK-free contains an ionic buffered preservative system, sofZia™. Recently, Lewis et al compared travoprost BAK-free with BAK-preserved travoprost (TRAVATAN®, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) in a randomized, multi-center, parallel, double-masked trial (Lewis et al 2007). IOP control was statistically equivalent between treatment groups and less conjunctival hyperemia was observed with the BAK-free preparation, although it was not statistically significant.

The toxicity of travoprost with and without BAK has been compared with the commercial preparation of latanoprost in several laboratory trials. Several investigators have used corneal and conjunctival cell cultures to demonstrate that travoprost BAK-free is associated with less apoptosis and cytotoxicity compared with latanoprost (preserved with 0.02% BAK) (Yee et al 2006; Baudouin et al 2007; Epstein et al 2008). Similarly, McCarey and Edelhauser (2007) reported that treatment with travoprost BAK-free had no negative effect on the integrity of corneal epithelial tight junctions, whereas latanoprost use was associated with significant loss of tight junctions (p < 0.0001). In addition, Whitson et al (2006) found little corneal toxicity in rabbits treated with travoprost BAK-free, whereas latanoprost caused superficial cell loss. Unfortunately, few data are available that evaluate the clinical benefit of eliminating BAK from prostaglandin analog therapy.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the safety, tolerability and efficacy of travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution compared to previous use of either latanoprost or bimatoprost monotherapy. The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), a validated English-language questionnaire, was used examine the prevalence of dry eye/OSD complaints in glaucoma patients (Schiffman et al 2000).

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were adults with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension treated with either latanoprost (Xalatan®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) or bimatoprost (Lumigan®, Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) monotherapy who demonstrated a need for greater tolerability and were judged by their physician to be a good candidate for travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution. The design was a multi-center, prospective, open-label, historical control study. Patients enrolled for this study were recruited from 65 clinical sites across the US.

Patients included in this study were at least 18 years of age; able to read and complete the OSDI questionnaire in English; had a clinical diagnosis of ocular hypertension or primary open-angle, pigment dispersion, or exfoliation glaucoma; treated with either latanoprost or bimatoprost monotherapy for at least 1 week, the last dose of which was instilled correctly so the patient was within the dosing cycle at Visit 1; best-corrected Snellen visual acuity of 20/200 or better in each eye; and IOP ≤30 mmHg in both eyes.

Exclusion criteria included primary or secondary glaucoma not listed in inclusion criterion; untreated history of narrow angles in either eye; concurrent infectious/non-infectious conjunctivitis, keratitis, or uveitis in either eye; blepharitis (non-clinically significant or prostaglandin-induced conjunctival injection was allowed); intraocular conventional surgery or laser surgery in study eye(s) less than 3 months prior to Visit 1; risk of visual field or visual acuity worsening as a consequence of participation in the trial; anticipated use of ocular or oral corticosteroids for more than 2 weeks total during the trial; and contact lens use in the study eye(s).

Procedures

All patients signed an Institutional Review Board-approved informed consent agreement and met the inclusion/exclusion criteria before any procedures were performed. Eligible patients had an ocular and systemic history taken. Patients then discontinued previous therapy and received 1 bottle of travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution (TRAVATAN Z®, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) and a prescription for TRAVATAN Z®, to be used once every evening in the study eye(s).

Patients returned for Visit 2 at Week 12, which must have been conducted at the same time of day (± 1 hour) as Visit 1. Patients who did not take their travoprost BAK-free as prescribed the day before the visit were rescheduled. Patients may have been examined by the investigator at any time between Visits 1 and 2 but these were not considered study visits. However, if the patient was discontinued from travoprost BAK-free before Visit 2, that visit was considered a study exit visit.

At Visits 1 and 2, Goldmann applanation tonometry, conjunctival hyperemia grading (by a photographic scale), Snellen visual acuity, and slit lamp biomicroscopy assessments were made. Patients completed the OSDI symptom questionnaire at Visits 1 and 2 and provided a global preference response at Visit 2. Additionally, adverse events were recorded at Visit 2.

Administration and calculation of OSDI score

The OSDI is a validated questionnaire designed to measure the severity of symptoms associated with ocular surface disease (Schiffman et al 2000). The OSDI questionnaire was handed to the patients and they were instructed to answer the questions on their own without any assistance. Patients were asked to answer all questions by placing a check in the box that corresponded to their symptoms. The individual answers corresponded to a specific value; all of the time = 4, most of the time = 3, half of the time = 2, some of the time = 1, and none of the time = 0. Those questions to which the patients responded not applicable (N/A) and questions that were not answered were not factored into the score calculation.

The classification of normal, mild, moderate, or severe OSD was determined on a scale from 0 to 100. OSD severity was classified as follows: normal (0–12), mild (13–22), moderate (23–32), and severe (33–100).

Statistics

All data analyses were two-sided. An α-level of 0.05 was used to declare statistical significance. A per-protocol, average eye analysis was used. Internet-based electronic data capture was used for the trial.

The change in IOP from previous prostaglandin analog therapy (latanoprost or bimatoprost), to travoprost BAK-free was analyzed by the paired t-test within each prior treatment or the combined population (Book 1978).

A one-way ANOVA test also was utilized to evaluate differences in hyperemia grading (grade 0–3) and OSDI scores for both prior medications compared to travoprost BAK-free. The paired t-test within an ANOVA was used to evaluate differences among individual preparations. A modified Bonferroni correction (α/6) was used to adjust p-level for individual OSDI questions in order to declare statistical significance.

Adverse events related to travoprost BAK-free therapy were not analyzed statistically because unsolicited adverse event data related to bimatoprost or latanoprost therapy were not collected at Visit 1.

Results

Patients

Enrolled in this study were 813 patients, of whom 17 were protocol violations. Of the 796 eligible patients, 105 (13%) did not complete the study. Therefore, 691 completed the study per protocol. The most common reasons for early discontinuation were related and unrelated adverse events (n = 45; 6%), lost to follow-up (n = 17; 2%), non-compliance (n = 11; 1%), and withdrew consent (n = 10; 1%). The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation were conjunctival hyperemia (n = 20; 3%), ocular irritation (n = 12; 2%), burning (n = 7; 1%), and 5 each (1%) for reduced vision and itching. No other ocular complaint was cited more than 2 times. Patients may have had more than 1 complaint.

Of 796 eligible patients, 61% were female and 77% were Caucasian (Table 1). The average age was 69.4 ± 11.8 years. Most patients (89%) had primary open-angle glaucoma. The most common associated ocular diagnoses at baseline were conjunctival hyperemia (n = 33; 4%), cataract (n = 20; 3%), and pseudophakia (n = 17; 2%); the most common systemic diagnoses were systemic hypertension (n = 576; 72%), lipid disorder (n = 254; 32%), and diabetes (n = 220; 28%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Eligible patients N = 796 n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 69.4 ± 11.8 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 311 (39) |

| Female | 485 (61) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 610 (77) |

| African-American | 110 (14) |

| Hispanic | 39 (5) |

| Asian | 31 (4) |

| Other | 6 (1) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Primary open-angle glaucoma | 708 (89) |

| Ocular hypertension | 77 (10) |

| Exfoliative glaucoma | 8 (1) |

| Pigment dispersion glaucoma | 3 (0.4) |

Ocular surface disease symptoms

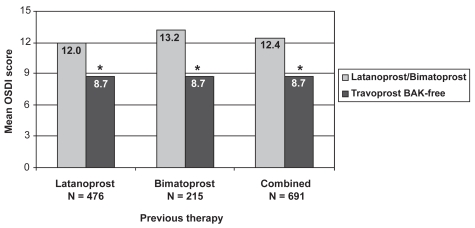

In a broad examination of OSDI scores, travoprost BAK-free demonstrated improved mean global scores (8.7 ± 11.3) compared with either latanoprost (12.0 ± 13.2, p < 0.0001) or bimatoprost therapy (13.2 ± 14.6, p < 0.0001; Figure 1). Use of travoprost BAK-free resulted in significantly improved scores versus prior therapy whether latanoprost and bimatoprost were considered individually or were combined (p < 0.0001). Individual questions which showed significant improvement after travoprost BAK-free therapy, following the Bonferroni correction, were sensitivity to light, gritty feeling, painful eyes, blurred vision, poor vision, reading difficulties, driving difficulties at night, working with the computer, windy conditions, and low humidity (p ≤ 0.0007).

Figure 1.

Improvement in ocular surface disease index scores with travoprost BAK-free according to previous prostaglandin analog use. *p < 0.0001.

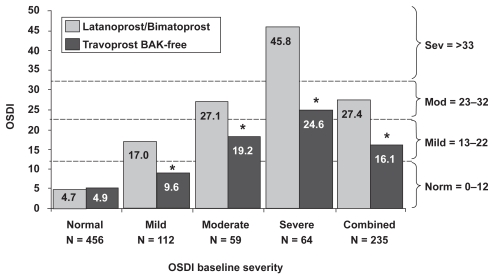

In a subset examination of the data, patients were grouped according to severity of their baseline visit (Visit 1) OSDI score (normal, mild, moderate, or severe). Patients remained grouped according to baseline OSDI scores and were analyzed for changes at Visit 2. Those patients classified as normal (n = 456) had a baseline score of 4.7 ± 3.8 compared to 4.9 ± 6.8 at Visit 2, which was not significantly different (p = 0.49; Figure 2). The mean baseline score for patients with mild symptoms (n = 112) was 17.0 ± 3.0 and improved to a mean score of 9.6 ± 7.7 after travoprost therapy; patients with moderate symptoms (n = 59) improved from 27.1 ± 2.1 to 19.2 ± 13.5; and patients with severe symptoms (n = 64) improved from 45.8 ± 10.9 to 24.6 ± 17.9. When symptomatic patients (those with mild, moderate, or severe symptoms) were pooled, their scores were reduced from a mean of 27.4 ± 13.5 to a mean of 16.1 ± 14.2. All changes from baseline in symptomatic patients were statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Regardless of OSD severity, the use of travoprost BAK-free for 3 months reduced the mean OSDI score by 1 category of severity: severe to moderate, moderate to mild, and mild to normal.

Figure 2.

Improvement in ocular surface disease index scores with travoprost BAK-free according to baseline severity. *p < 0.0001.

The use of travoprost BAK-free for 3 months reduced the mean OSDI score by at least 1 category of severity (severe to moderate, moderate to mild, or mild to normal) in 70.2% of the 235 patients with OSD symptoms at baseline (Table 2). Fifty-seven (46.3%) of 123 moderate or severe patients improved by a reduction in severity by at least 2 levels. Of the 64 severe patients, 15 (23.4%) improved to normal, decreasing the level of severity by 3 levels.

Table 2.

Patients with an OSDI score that improved by at least one level of severity

| OSDI severity grouping (baseline) | Patients improved to normal [n (%)] | Patients improved to mild [n (%)] | Patients improved to moderate [n (%)] | Patients improved by at least 1 level [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n = 112) | 79 (70.5%) | N/A | N/A | 79 (70.5%) |

| Moderate (n = 59) | 21 (35.6%) | 18 (30.5%) | N/A | 39 (66.1%) |

| Severe (n = 64) | 15 (23.4%) | 21 (32.8%) | 11 (17.2%) | 47 (73.4%) |

| Mild + Moderate + Severe (n = 235) | 115 (48.9%) | 39 (16.6%) | 11 (4.7%) | 165 (70.2%) |

Abbreviations: OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index.

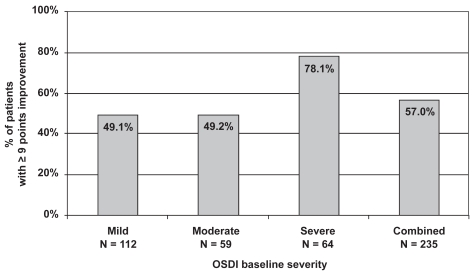

The number of patients with a clinically significant reduction in OSDI scores, defined as 9 points or more, was also examined (Figure 3). Of the 235 patients with mild to severe symptoms, 134 (57.0%) had a reduction of 9 points or more from their baseline OSDI score after 3 months of treatment with travoprost BAK-free. Approximately half of the patients with mild (49.1%) or moderate (49.2%) symptoms achieved clinically significant improvement, as did over three-quarters (78.1%) of patients with severe symptoms.

Figure 3.

Clinically significant improvement (≥9 points) in ocular surface disease index scores with travoprost BAK-free according to baseline severity.

Intraocular pressure

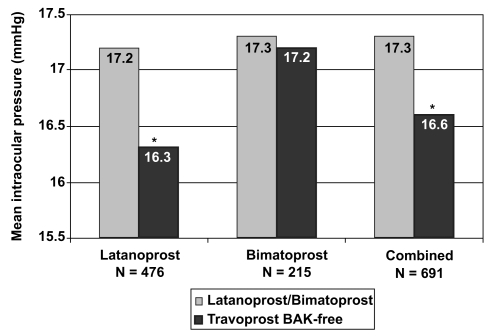

After a change in medications from their previous prostaglandin analog to travoprost BAK-free, patients experienced a statistically significant reduction in IOP (17.3 ± 3.6 vs. 16.6 ± 3.8 mmHg; p < 0.0001; Figure 4). When IOP was analyzed by specific prior prostaglandin analog therapy, a significant decrease in IOP was observed after changing from latanoprost to travoprost (p < 0.0001), but not from bimatoprost to travoprost (p = 0.5245).

Figure 4.

Change in mean IOP with travoprost BAK-free according to previous prostaglandin analog use. *p < 0.0001.

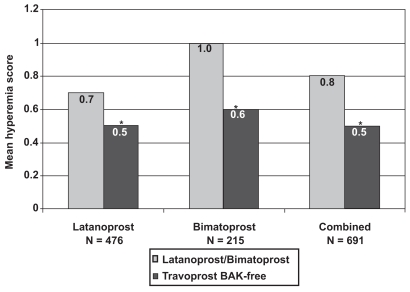

Hyperemia

Physicians graded hyperemia for all patients on a 0 to 3 scale at both visits. The baseline hyperemia scores were statistically different between latanoprost (0.7 ± 0.7) and bimatoprost (1.0 ± 0.9; p < 0.0001; Figure 5). However, both groups experienced a significant decrease in hyperemia with travoprost BAK-free (0.5 ± 0.6 and 0.6 ± 0.7, respectively; p < 0.0001). An examination of hyperemia, irrespective of the patient’s previous prostaglandin analog use, also resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the hyperemia score, from 0.8 ± 0.8 to 0.5 ± 0.6 (p < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Change in mean hyperemia scores with travoprost BAK-free according to previous prostaglandin analog use. *p < 0.0001.

Visual acuity

LogMAR visual acuity was significantly better with travoprost BAK-free versus prior therapy (0.167 ± 0.140 versus 0.174 ± 0.151, p = 0.04).

Adverse events

The most commonly reported unsolicited adverse events with travoprost BAK-free were conjunctival hyperemia (n = 49; 6%) and change in visual acuity (n = 28; 4%; Table 3). There were 5 serious adverse events in 3 patients: non-specific infection, vomiting and shortness of breath, aortic dissection, metastatic cancer of the liver, and abdominal rash. Investigators reported that none of these events were related to travoprost BAK-free.

Table 3.

Ophthalmic adverse events with travoprost BAK-free

| Description | n |

|---|---|

| Hyperemia | 49 |

| Change in visual acuity | 28 |

| Burning | 14 |

| Irritation | 9 |

Adverse events with an incidence of at least 1%.

Patient preference

The results for the global patient preference survey found 500 of the 691 patients (72.4%) favored travoprost BAK-free while 191 (27.6%) preferred the prior prostaglandin analog (p < 0.0001; Table 4). An examination based on specific prior prostaglandin analog use demonstrated that 74.6% of the patients previously using latanoprost and 67.4% previously using bimatoprost preferred travoprost BAK-free.

Table 4.

Patient preference (per patient analysis)

| Baseline prostaglandin analog | n | Preferred previous therapy | Preferred travoprost BAK-free | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latanoprost | 476 | 25.4% | 74.6% | <0.0001 |

| Bimatoprost | 215 | 32.6% | 67.4% | <0.0001 |

| Combined | 691 | 27.6% | 72.4% | <0.0001 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the safety, tolerability and efficacy of travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution compared with previous use of either latanoprost or bimatoprost monotherapy in a typical clinical situation.

The OSDI was the primary tool used to assess symptoms related to ocular surface disease (Ozcura et al 2007). After the change to travoprost BAK-free, global mean OSDI scores were significantly reduced from scores while taking latanoprost and bimatoprost, evaluated together or individually. This demonstrated statistically significant improvement in mean global scores on travoprost BAK-free (8.7 ± 11.3) from either latanoprost (12.0 ± 13.2) or bimatoprost therapy (13.2 ± 14.6).

In a subset examination of the data, patients were grouped according to baseline visit OSDI score. Regardless of the severity of OSD symptoms, the use of travoprost BAK-free for 3 months significantly reduced the mean OSDI score in each group enough to reduce the category of severity to the next lower level (severe to moderate, moderate to mild, and mild to normal). Additionally, the shifts in mean OSDI scores for each of the individual groups as well as for a group combining mild, moderate, and severe scores was approximately 9 points or greater (range, 8.0–21.2), confirming the clinical significance of this improvement (Miller et al 2006). The data were also examined on a per patient basis to explore how individual patients responded. Over 70% of patients experienced a decrease in their OSD symptoms by at least 1 level of severity after 3 months on travoprost BAK-free. Even more impressive is the fact that almost one quarter of the patients with a severe baseline score improved to the normal range after 3 months. Furthermore, 57% of symptomatic patients had a clinically significant improvement in their OSD symptoms. The absence of BAK in the travoprost preparation may have contributed to the improved comfort experienced by the study patients. Consequently, by using travoprost BAK-free, a physician now has a way to prescribe chronic prostaglandin therapy while possibly helping improve a patient’s OSD symptoms.

These findings may have clinical importance for glaucoma patients beyond the lessening of OSD symptoms. A consequence of a more comfortable ocular surface, as a result of using travoprost BAK-free, may potentially be an improvement in patient adherence to the IOP-lowering regimen, which could in turn improve IOP control.

This study demonstrated that IOP was significantly reduced after the initiation of travoprost BAK-free therapy compared to prior prostaglandin analog therapy. The results of this study are consistent with the travoprost BAK-free regulatory trial, which demonstrated travoprost BAK-free was at least as efficacious as the BAK-preserved preparation of travoprost (Lewis et al 2007). Furthermore, a randomized, double-masked study by Gross and colleagues demonstrated that the two formulations of travoprost (travoprost with BAK and travoprost BAK-free) had similar efficacy, including a prolonged duration of action showing >6 mmHg reduction in IOP 60 hours after final dose of either drug (Gross et al 2008). However, physicians must interpret the efficacy data from the current trial with caution because of its open-label design, which may have introduced bias into the results for IOP.

Additionally, the reduction in conjunctival hyperemia experienced by patients after the initiation of travoprost BAK-free correlated well with reports that BAK has been shown to worsen conjunctival inflammation (Noecker et al 2004; Yee et al 2006; Kahook et al 2008). BAK might further worsen conjunctival hyperemia already present due to prostaglandin analog therapy, which is associated with nitric oxide synthesis within the conjunctival vessels (Astin et al 1994). Removing the BAK from IOP-lowering medications might reduce inflammation and assist in reducing conjunctival vessel dilation; this hypothesis is supported by the lessened hyperemia observed in the study.

Overall, the incidence of patients discontinuing due to an adverse event related to travoprost BAK-free therapy was very low. Conjunctival hyperemia was the most commonly cited patient complaint (6%), as well as the most common adverse event leading to discontinuation (3%). However, this must be mentioned in the context that 4% of patients were diagnosed with conjunctival hyperemia at the baseline visit.

Visual acuity was also slightly improved after 3 months of travoprost BAK-free therapy. The change was small and may have been by chance. However, if corneal tear film stability is improved by removal of the BAK, as indicated by Manni et al (2005), visual acuity may have improved as a result of changing to a BAK-free preparation.

This study suggests that patients previously treated with BAK-preserved prostaglandin analog therapy and subsequently changed to travoprost BAK-free had, on average, similar to slightly better IOP control while experiencing reduced anterior segment symptoms and lessened hyperemia.

The study did not evaluate differences in efficacy and safety between BAK-free travoprost and other prostaglandin therapy in a parallel, randomized, masked fashion. The change in therapeutic regimen may have fostered the expectation in some patients of a superior therapy, possibly resulting in more favorable subjective outcomes than may have been observed in a randomized, double-masked study. More research is needed in an adequately controlled prospective trial to confirm the findings noted in this study. In addition, this study was not designed to address the long-term clinical outcomes of travoprost BAK-free therapy. Further research with prostaglandin analogs will clarify the best therapeutic approach with this class of medicine for patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This clinical trial was supported by an unrestricted grant from Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, Texas.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Astin M, Stjernschantz J, Selén G. Role of nitric oxide in PGF2 alpha-induced ocular hyperemia. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:401–7. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin C, Riancho LM, Warnet JM, et al. In vitro studies of anti-glaucomatous prostaglandin analogues: travoprost with and without benzalkonium chloride and preserved latanoprost. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4123–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book SA. Essentials of statistics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. pp. 117–22. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein SP, Chen D, Asbell PA. The effect of travoprost Z, latanoprost and their individual components on the ocular surface (corneal and conjunctival epithelium). Presented at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO); May 7, 2008; Fort Lauderdale, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Fechtner R, Budenz D, Godfrey D. Prevalence of ocular surface disease symptoms in glaucoma patients on IOP-lowering medications. Poster presented at: Annual meeting of the American Glaucoma Society; March 8, 2008; Washington DC. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gross RL, Peace JH, Smith SE, et al. Duration of IOP reduction with travoprost BAK-free solution. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:217–22. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815a3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenen N, Baudouin C, Pouliquen P, et al. Ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative-free glaucoma medications. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:341–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahook MY, Noecker RJ. Comparison of corneal and conjunctival changes after dosing of travoprost preserved with sof Zia, latanoprost with 0.02% benzalkonium chloride, and preservative-free artificial tears. Cornea. 2008;27:339–43. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815cf651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens EV, de Jong CA, Stolwijk TR, et al. Effect of timolol with and without preservative on the basal tear turnover in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:339–42. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RA, Katz GJ, Weiss MJ, et al. Travoprost BAC-free Study Group. Travoprost 0.004% with and without benzalkonium chloride: a comparison of safety and efficacy. J Glaucoma. 2007;16:98–103. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000212274.50229.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni G, Centofanti M, Oddone F, et al. Interleukin-1beta tear concentration in glaucomatous and ocular hypertensive patients treated with preservative-free nonselective beta-blockers. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarey B, Edelhauser H. In vivo corneal epithelial permeability following treatment with prostaglandin analogs with or without benzalkonium chloride. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:445–51. doi: 10.1089/jop.2007.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KL, Mink DR, Mathias SD, et al. Estimating the minimal clinical important difference of the Ocular Surface Disease Index®: preliminary findings [abstract] 2006 Abstract obtained from www.isoqol.org/2006AbstractsBook.pdf.

- Noecker RJ, Herrygers LA, Anwaruddin R. Corneal and conjunctival changes caused by commonly used glaucoma medications. Cornea. 2004;23:490–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000116526.57227.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcura F, Aydin S, Helvaci MR. Ocular surface disease index for the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2007;15:389–93. doi: 10.1080/09273940701486803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisella PJ, Pouliquen P, Baudouin C. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:418–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein OD, Munoz B, Tielsch JM, et al. Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:723–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitson JT, Cavanagh HD, Lakshman N, et al. Assessment of corneal epithelial integrity after acute exposure to ocular hypotensive agents preserved with and without benzalkonium chloride. Adv Ther. 2006;23:663–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02850305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee RW, Norcom EG, Zhao XC. Comparison of the relative toxicity of travoprost 0.004% without benzalkonium chloride and latanoprost 0.005% in an immortalized human cornea epithelial cell culture system. Adv Ther. 2006;23:511–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02850039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee RW. The effect of drop vehicle on the efficacy and side effects of topical glaucoma therapy: a review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:134–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328089f1c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]