Abstract

Managed relocation (MR) has rapidly emerged as a potential intervention strategy in the toolbox of biodiversity management under climate change. Previous authors have suggested that MR (also referred to as assisted colonization, assisted migration, or assisted translocation) could be a last-alternative option after interrogating a linear decision tree. We argue that numerous interacting and value-laden considerations demand a more inclusive strategy for evaluating MR. The pace of modern climate change demands decision making with imperfect information, and tools that elucidate this uncertainty and integrate scientific information and social values are urgently needed. We present a heuristic tool that incorporates both ecological and social criteria in a multidimensional decision-making framework. For visualization purposes, we collapse these criteria into 4 classes that can be depicted in graphical 2-D space. This framework offers a pragmatic approach for summarizing key dimensions of MR: capturing uncertainty in the evaluation criteria, creating transparency in the evaluation process, and recognizing the inherent tradeoffs that different stakeholders bring to evaluation of MR and its alternatives.

Keywords: assisted migration, climate change, conservation biology, conservation strategy, sustainability science

Managed relocation (MR) is an intervention technique aimed at reducing negative effects of climate change on defined biological units such as populations, species, or ecosystems. It involves the intentional movement of biological units from current areas of occupancy to locations where the probability of future persistence is predicted to be higher. The underlying motivation of MR is to reduce the threat of diminished ecosystem services or extinction from climate change. These threats interact with other facets of global change, including land-use change and biological invasions. MR has been used sparingly to date, but its importance as a conservation strategy is likely to grow as changes in climate become pronounced in the coming decades (1–3).

Several authors have evaluated the potential benefits and risks of MR, and its current prevalence (3–6), but little effort has been made to develop a robust strategy for evaluating the suite of benefits and risks associated with the strategy. Hoegh-Guldberg and colleagues (1) recently proposed a stepwise linear process to determine when it is appropriate to consider MR. Their framework identifies key information necessary to perform cost-benefit analyses. They identify several routes that do not lead to MR as the recommended strategy, and they envision MR as a last-ditch option should other conservation strategies be inadequate. In response to their analysis, several authors expressed additional concerns regarding specific risks associated with MR (7–9). Nevertheless, the decision-making process of whether or not MR should be performed has continued to receive little attention.

A tree approach to MR has several drawbacks that illustrate crucial aspects of the challenges presented by MR. First, complex conservation decisions such as MR are inherently poorly suited for resolution via decision-trees because a linear approach cannot accommodate the multiple dimensions of decision making (10). By allowing only 1 route to a particular decision, it is difficult to evaluate the relative merits of competing conservation options. Second, conservation decision-making tools are most valuable when they help to distinguish the social and cultural values used to judge acceptable risk from determinations of risk itself (where “risk” is the product of the probability of occurrence and potential consequence). A linear decision process does not depict choices between competing interests and needs. For example, deciding not to undertake MR could, in some cases, lead to extinction of some species to preserve other conservation values such as ecological integrity, ecosystem resilience, productivity, etc. Third, applied ecology, including MR, is fraught with uncertainty that cannot be adequately expressed by a decision tree with alternative pathways that imply sharp dichotomies (i.e., “yes” or “no”). Fourth, MR should probably not be defined, a priori, as the approach of last resort, but rather one of a portfolio of options.

Here, we propose a decision-making framework for MR that is multidimensional and informed by differences in social values. This framework can be used to characterize uncertainty and help establish priorities for MR among biological units and alternative conservation strategies. In many cases, alternate stakeholders will follow our framework and evaluate the relative measures differently (11). In so doing, the data and values used by each group are revealed.

Our multivariate framework can be conceptualized as a N-dimensional set of criteria that collectively address the costs and benefits of MR relative to other conservation strategies. Table 1 lists a subset of possible criteria. We distinguish criteria that are ecological from those that are determined by social values. Ecological criteria are subject to evaluation through available data or expert judgment, and evaluation of these criteria may change over time as new experiments and analyses are pursued. By contrast, the evaluation of social criteria changes as information moulds public perception and as cultural and social values shift over time. These 2 types of criteria interact; for example, social values inform which ecological studies are pursued. In many cases, MR may bring long-held conservation objectives into opposition, such as the maintenance of ecosystem integrity versus the importance of preserving individual species. Given the potential for strong disagreement, it becomes increasingly important that decisions on MR emerge from a transparent process that reveals the nature of the criteria invoked (12–15).

Table 1.

Ecological and social considerations for evaluating individual cases of managed relocation (MR), wherein the goal is to prevent the loss of a species or population

| Ecological criteria | Social criteria |

|---|---|

| Focal impact* | |

|

Likelihood of outcome: Extinction Decline in geographic distribution Decline in abundance within geographic distribution Indirect effects of decline on community members and community composition |

Likelihood and consequence of outcome: Cultural importance of the target and its community (e.g., is the target a flagship or iconic species? is the historic integrity of the community important?) |

|

Consequence of outcome: Uniqueness (phylogenetic, functional, etc.) Geographic distribution (common versus rare; small versus large range) The potential for reversibility (e.g., if no action were taken and the species went extinct in the wild, are there ex situ individuals available for population reestablishment) |

Equity of the impact on particular groups of people Concerns about the harm to individual organisms subjected to MR Financial loss whether focal unit declines in abundance or goes extinct |

| Collateral impact† | |

|

Likelihood of outcome: Decline or extinction of native species in recipient region Decline or loss of ecological functions in recipient region |

Likelihood and consequence of outcome: Cultural importance of the target and its community (e.g., is the target a flagship or iconic species? Is the historic integrity of the community important?) |

|

Consequence of outcome: Uniqueness of affected focal units Geographic distribution of affected focal units Effect on existing conservation efforts Degree to which effects are reversible (e.g., whether the focal unit could be easily controlled or managed once established in the recipient region) |

Equity of the impact on particular groups of people Concerns about the harm to individual organisms subjected to MR Financial loss whether focal unit declines in abundance or goes extinct |

| Feasibility‡ | |

| Degree to which the target can be captured, propagated, transported, transplanted, monitored, or controlled Availability of appropriate sites for translocation Sustainability of MR in achieving conservation objectives (e.g., whether MR for a given focal unit would need to be performed iteratively to match changes in environmental conditions) |

Economic cost Legal or regulatory obstacles (permits, etc.) that would hinder or restrict the capacity to conduct MR Regulations or laws that facilitate MR |

| Acceptability§ | |

| N.A. | Willingness to accept potentially irreversible consequences (cultural, aesthetic, or economic) Willingness to support action Trust and acceptance of ecological information Aesthetic, cultural, and moral attitudes toward focal and collateral units Concern that a focal unit's protection will restrict land in the recipient region from being managed or developed Willingness to support new laws and policies that encourage or enable MR |

This list is illustrative, not exhaustive, and will vary by case and stakeholder group. Additional criteria would be needed to consider MR if the goal was to replace a species complex or ecological function that had been lost from a system. In the case of focal and collateral impact, risk is measured by the likelihood of an outcome times the consequence of that outcome. N.A., not applicable.

*Impact on focal unit and its community from climate change and exacerbating effects of MR.

†Effect of focal unit in recipient region.

‡Constraints on or opportunities for MR.

§Societal willingness to pursue MR.

To illustrate this decision-support tool, we propose that criteria involved in the evaluation of MR can be categorized into 4 general classes (Table 1). These are 1) the impacts of conducting (or not conducting) MR on a given focal unit, 2) the impacts of MR activities on the recipient ecosystem, 3) the practical feasibility of conducting MR, and 4) the social acceptability of the action. The challenge of decision-making is then distilled to settling on a suite of attributes for grading in each class, ranking attributes within a class, and assigning a qualitative or quantitative score to each class. Together, the criteria-classes reveal the net benefits and risks associated with MR as perceived by the individual or group performing the evaluation exercise.

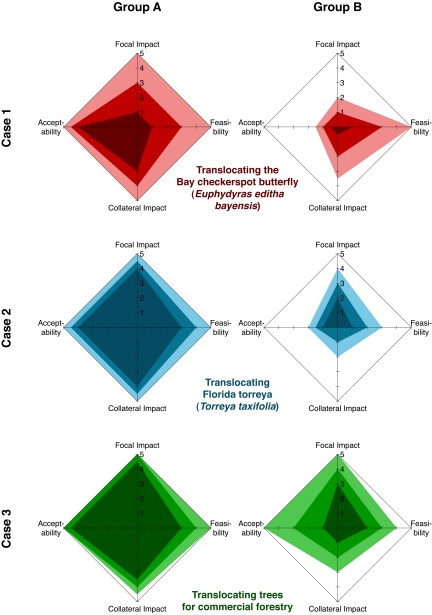

We illustrate a 4-class decision tool by displaying each class as a single axis in 2-D space (Fig. 1). Two axes capture risk, whereas 2 others specify implementation constraints on MR. Axis 1 (Focal impact) measures impact on the focal unit of interest and its community via indirect effects. These include impacts that occur without MR because of climate change and exacerbating effects of MR itself. Axis 2 (Collateral impact) measures the collateral effects of MR on nontarget organisms and ecosystems in the recipient region; this axis is scaled to decrease in magnitude with distance from the origin. Both of these axes capture ‘risk,’ the probability of an effect and the consequence of that effect (Table 1). Although probabilities of risk are amenable to transparent estimation and are theoretically knowable in many circumstances, limitations in time and resources impart bounds on the certainty of these estimates. Axis 3 (Feasibility) relates primarily to technical, logistical, or legal issues involving the practicality of implementation and the likelihood that MR (or any alternate conservation strategy) will achieve its stated objectives. Axis 4 (Acceptability), in contrast, captures the tolerance of MR activities, and its measurement resides largely in the domains of sociology and ethics (Table 1). Values for each of the first 3 axes include both biological (e.g., persistence versus extinction, invasion versus system integrity) and social value (e.g., economic and cultural importance of the focal unit) components, whereas Axis 4 is primarily driven by normative values that may be informed by the other axes (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

A decision-making heuristic for managed relocation (MR). This heuristic is illustrated for 2 stereotyped stakeholders in each of 3 hypothetical cases (see Methods). Each case is evaluated along 4 axes: 1. Focal impact, 2. Collateral impact, 3. Feasibility, and 4. Acceptability (Table 1). These axes are scaled from 0–5, with low to high scores, respectively, except for the collateral impacts axis, which is scaled inversely (such that 5 is the lowest collateral impact). These axes create a 4-dimensional space but are illustrated in 2 dimensions. Consequently, polygons connecting the axes do not represent the actual volume of this space, but their shapes do convey a perspective about MR (see Text). Polygons with medium shading show mean scores; darker and lighter polygons show the lower and upper bounds, respectively, of uncertainty in these estimates. Case 1 illustrates how differing conservation groups could differentially evaluate MR for the Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha bayensis); this species is threatened by climate change and habitat destruction. Case 2 illustrates evaluations of MR for Torreya taxifolia, an endangered tree with a small endemic range in northern Florida that is threatened by disease and potentially by climate change. Case 3 is for MR of trees used in production forestry in Canada. All 3 cases show how different stakeholder groups could come to very different conclusions about MR, even with the same information.

For each axis, teasing apart the relative effects of multiple criteria to generate a single value is nontrivial, but the exercise should be traceable, transparent, and repeatable. Scores on each axis also should be comparable among axes (i.e., on a standardized scale) and all values should be greater than 0. If the Focal impact axis were 0, for example, MR is unnecessary. Furthermore, one would expect all interventions to result in at least some collateral effect. Error bars on the values for each axis denote the level of uncertainty from incomplete information and/or variation among score assignments within a stakeholder group.

Given the configuration of the 4 axes in Fig. 1, a line can be drawn connecting the values and error bars on each axis. In general, polygons can be evaluated against each other. Diamond shapes indicate symmetry in rankings among the criteria. Triangles indicate asymmetrical scores in at least 1 axis, and narrow diamonds or vertical and horizontal stick shapes indicate asymmetrical scores in multiple axes. Larger shapes indicate overall higher scores in the evaluation criteria. Note that the shape formed by the connection of values and error bars on each axis is not the area of the actual parameter space because the heuristic comprises 4 dimensions depicted in 2 dimensions. Nonetheless, these 2-D shapes can help to inform decision making on MR and, as more cases are evaluated, should contribute to increasingly robust policies and strategies.

We illustrate the heuristic approach with 3 cases interpreted by 2 stakeholder groups that are crafted from available information (Fig. 1). These hypothetical stakeholders do not reflect actual individuals or groups but illustrate differing feasible outcomes in applying the tool. Our cases consider changes in species composition but the tool could be applied to biological units below the species level. Because cases differ along the 4 axes, our framework can be used to prioritize cases for MR consideration. The tool also can be used iteratively to compare alternative strategies for minimizing the biotic effects of climate change such as the creation of corridors or the application of management techniques in historical sites of occupancy.

The heuristic provides a multidimensional and transparent tool that incorporates both the ecological and social criteria that underlie controversial issues in conservation. Like other regulatory tools premised on the transparent disclosure of information, this heuristic could improve decision making by informing actors about the benefits and costs of alternative courses of action, catalyzing public participation and deliberation on an action's effects and alternatives, and increasing the public acceptability and legitimacy of decisions (16–21). We also anticipate that stakeholder groups using this tool are likely to find commonality in their views on MR that could serve as a starting point for policy discussion. A decision of nonaction based on intractable conservation disagreement may often result in a loss of biodiversity.

Materials and Methods

To illustrate the multidimension decision heuristic, we qualitatively evaluated 3 cases where assisted migration has or may be pursued, and we consider these cases from the point of view of 2, broadly stereotyped, stakeholders (Fig. 1). These 2 groups broadly fall into a proponent (group A) and opponent (group B) of MR, but real cases with multiple stakeholders will reveal less dichotomous perspectives. We have not surveyed these stakeholders or identified individuals that might fall into our hypothetical characterization. Instead, we built characterizations based on published data about each species, mission statements of groups concerned with each case, and discussion about species management for each case that can be found in the public domain. Detailed information about each case and the reasoning behind values selected are given in online methods, see SI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grants DEB 0741792 and 0741921 in support of the Managed Relocation Working Group, DST-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology (D.M.R), and a Cedar Tree Foundation grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902327106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. Assisted colonization and rapid climate change. Science. 2008;321:345–346. doi: 10.1126/science.1157897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein L, et al. In Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. Climate change 2007 synthesis report. Summary for policy makers. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLachlan JS, Hellmann JJ, Schwartz MW. A framework for debate of assisted migration in an era of climate changes. Conserv Biol. 2007;21:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunter M. Climate change and moving species: Furthering the debate on assisted colonization. Conserv Biol. 2007;21:1356–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller JM, Hellmann JJ. An assessment of invasion risk from assisted migration. Conserv Biol. 2008;22:562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Veken S, Hermy M, Vellend M, Knapen A, Verheyen K. Garden plants get a head start on climate change. Front Ecol Environ. 2008;6:212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson I, Simkanin C. Skeptical of assisted colonization. Science. 2008;322:1048–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.322.5904.1048b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang D. Assisted colonization will not help rare species. Science. 2008;322:1049. doi: 10.1126/science.322.5904.1049a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapron C, Samelius G. Where species go, legal protections must follow. Science. 2008;322:1049–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.322.5904.1049b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire LM. In: Principles of Conservation Biology. 3rd Ed. Groom MJ, et al., editors. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2006. pp. 638–640. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minteer BA, Collins JP. Why we need an “ecological ethics”. Front Ecol Environ. 2005;3:332–337. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess J, et al. Deliberative mapping: A novel analytic-deliberative methodology to support contested science-policy decisions. Publ Underst Sci. 2007;16:299–322. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stirling A. Analysis, participation and power: Justification and closure in participatory multi-criteria analysis. Land Use Policy. 2007;23:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgman MA. Risks and Decisions for Conservation and Environmental Management. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider SH, et al. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Parry ML, et al., editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. pp. 779–810. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regan HM, Colyvan M, Markovchick-Nicholls L. A formal model for consensus and negotiation in environmental management. J Ecol Manage. 2006;80:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svancara LK, et al. Policy-driven versus evidence-based conservation: A review of political targets and biological needs. BioScience. 2005:989–995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodgers W. Environmental law trivial test No. 2 NEPA. Environmental Law. 1994:809–815. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karkkainen BC. Toward a smarter NEPA: Monitoring and managing government's environmental performance. Columbia Law Review. 2002;102:903–916. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camacho AE. Mustering the missing voices: A collaborative model for fostering equality, community involvement and adaptive planning in land use decisions installment one. Stanford Environm Law J. 2005;24:269–286. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camacho AE. Can regulation evolve? Lessons from a study in maladaptive management. UCLA Law Review. 2007;55:293–344. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.