Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To explore women’s perspectives on the acceptability and content of reminder letters for screening mammography from their family physicians, as well as such letters’ effect on screening intentions.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional mailed survey followed by focus groups with a subgroup of respondents.

SETTING

Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

One family physician was randomly selected from each of 23 family health networks and primary care networks participating in a demonstration project to increase the delivery of preventive services. From the practice roster of each physician, up to 35 randomly selected women aged 50 to 69 years who were due or overdue for screening mammograms and who had received reminder letters from their family physicians within the past 6 months were surveyed.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Recall of having received reminder letters and of their content, influence of the letters on decisions to have mammograms, and interest in receiving future reminder letters. Focus group interviews with survey respondents explored the survey findings in greater depth using a standardized interview guide.

RESULTS

The response rate to the survey was 55.7% (384 of 689), and 45.1% (173 of 384) of responding women reported having mammograms in the past 6 months. Among women who recalled receiving letters and either making appointments for or having mammograms, 74.8% (122 of 163) indicated that the letters substantially influenced their decisions. Most respondents (77.1% [296 of 384]) indicated that they would like to continue to receive reminders, and 28.9% (111 of 384) indicated that they would like to receive additional information about mammograms. Participants in 2 focus groups (n = 3 and n = 5) indicated that they thought letters reflected a positive attitude of physicians toward mammography screening. They also commented that newly eligible women had different information needs than women who had had mammograms done in the past.

CONCLUSION

Reminder letters were considered by participants to be useful and appeared to influence women’s decisions to undergo mammography screening.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Établir l’opinion des femmes sur la pertinence et le contenu des lettres de rappel de leur médecin de famille pour le dépistage par mammographie et l’influence de ces lettres sur l’intention d’y donner suite.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête postale transversale suivie de groupes de discussion avec quelques répondantes.

CONTEXTE

Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Un médecin de famille a été choisi dans chacun des 23 réseaux de santé familiale et de soins primaires qui participaient à un projet de démonstration pour augmenter la dispensation des services préventifs. Jusqu’à 35 femmes âgées de 50 à 69 ans qui devaient subir une mammographie ou tardaient à le faire, et qui avaient reçu une lettre de rappel de leur médecin au cours des 6 derniers mois, ont été choisies au hasard dans la clientèle de chaque médecin pour participer à l’enquête.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Le souvenir d’avoir reçu la lettre et de son contenu, l’influence de la lettre sur la décision de subir la mammographie et l’intérêt à recevoir des lettres de rappel dans le futur. Les groupes de discussion avec des répondantes à l’enquête ont examiné plus en détail les résultats de l’enquête à l’aide d’un guide d’entrevue standardisé.

RÉSULTATS

Le taux de réponse à l’enquête était de 55,7 % (384 sur 689); pour celles ayant subi une mammographie au cours des 6 derniers mois, il était de 45,1 % (173 sur 384). Parmi celles qui se souvenaient d’avoir reçu la lettre et qui avaient pris rendez-vous ou avaient subi une mammographie, 74,8 % (122 sur 163) indiquaient que la lettre avait fortement influencé leur décision. La plupart des répondantes (77,1 % [296 sur 384]) souhaitaient recevoir d’autres rappels et 28,9 % (11 sur 384) disaient qu’elles aimeraient recevoir plus d’information sur la mammographie. Les participantes aux 2 groupes de discussion (n = 3 et n = 5) mentionnaient qu’elles croyaient que les lettres reflétaient une attitude positive des médecins envers le dépistage par mammographie; elles ajoutaient que les femmes nouvellement admisibles avaient des besoins d’informations différents de celles qui avaient déjà subi des mammographies.

CONCLUSION

Aux dires des participantes, les lettres de rappel sont utiles et semblent influer sur la décision de subir une mammographie de dépistage.

Screening mammography is the primary method used to reduce breast cancer morbidity and mortality. Canadian guidelines recommend biennial screening for women aged 50 to 69 years,1 as the incidence of breast cancer increases with age.2 Screening mammography can detect cancers before symptoms are present, potentially leading to improved treatment and increased survival. Screening mammography is estimated to provide a relative risk reduction in breast cancer mortality of 15% to 20%.3 In order to attain a significant decrease in mortality at the population level, it is estimated that at least 70% of eligible women need to be regularly screened.3,4 This estimate is in line with the goal of Cancer Care Ontario to increase the participation rate of women aged 50 to 69 years in the Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) to 70% by 2010.5

Approximately 56% of women between the ages of 50 and 69 in Ontario report that they have received preventive screening mammograms within the past 2 years5; this proportion is slightly higher among women who have regular family physicians.6 It is estimated that 15% to 30% of eligible women in Ontario obtain mammograms through the OBSP.7 Most women in Ontario rely on opportunistic referral for screening by their family physicians. Therefore, wide-scale implementation of practice-based reminder and recall systems might be an important strategy to improve screening rates and thus reduce breast cancer mortality.8

A Cochrane review of 16 community-based randomized controlled trials looked at strategies for increasing participation rates in breast cancer screening programs and concluded that there are 5 effective strategies for inviting women to use community services: letters of invitation (odds ratio [OR] 1.66, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43 to 1.92); mailed educational materials (OR 2.82, 95% CI 1.96 to 4.02); letters of invitation and telephone calls (OR 2.53, 95% CI 2.02 to 3.18); telephone calls (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.70 to 2.23); and training activities with direct reminders (OR 2.46, 95 CI 1.72 to 3.50).9

Despite the evidence that personalized reminder letters improve uptake of mammography screening rates, we know little about women’s views on the content and acceptability of such letters from their family physicians. Studies have found that women who perceive their physicians to be supportive of screening mammography are much more likely to have mammography done.10,11 In these studies, however, preventive counseling was conducted in person; it remains unclear how women perceive written reminder letters from their own family physicians. Eliciting patient feedback on reminder systems for preventive services can help ensure that features patients consider important are included, potentially improving compliance with the recommendations.12 As part of the evaluation of a larger demonstration project of a reminder and recall system for preventive care services (Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-strategy Prevention Tools: P-PROMPT), we examined women’s views on the acceptability, usefulness, and influence of reminder letters for mammography using a mixed methods study.

METHODS

A multistage cluster sampling procedure was employed to select a representative sample of eligible women. Using a random number generator, we selected 1 family physician from each of 23 family health networks and primary care networks in southwestern Ontario participating in the demonstration project (N = 249 physicians). Physicians were eligible if they had sent 30 or more mammography reminder letters in the past 6 months and had not been selected to participate in other surveys conducted concurrently by the project. All 23 of the selected physicians agreed to participate. From the roster of each physician, we randomly selected up to 35 women between 50 and 69 years of age who were due or overdue for mammography screening and had received reminder letters from their physicians within the past 6 months. Postal surveys typically obtain response rates of approximately 60%.13 The target sample size was 400 completed questionnaires, which allowed for a 5% margin of error at a 95% confidence level; therefore, approximately 700 questionnaires needed to be mailed (30 patients from each of 23 physicians). The sampling frame only included women who were mailed reminder letters. We increased the cutoff figure used in the inclusion criteria and the sample size calculation to 35 randomly selected women per physician because physicians were sent a list of the identified patients and were asked to remove any patients that should not be contacted. In some practices there were fewer than 35 eligible women according to our inclusion criteria, and after removal of the women who were no longer with the practices or who had moved or died, our final sample consisted of 689 eligible women.

Patient survey

The survey packs (N = 689), including cover letters printed on the physicians’ practice letterheads and signed by the physicians, were mailed with prestamped return envelopes in December 2005 to the same addresses that had been used for the reminder letters. We used a modified Dillman method,14 with 1 follow-up survey package sent to each nonrespondent 6 weeks after the original mailing. The self-administered survey consisted of 18 questions that sought information about patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, recall of reminder letters and their contents, and current screening status. Additionally, women who had made appointments or who had had mammograms after receiving the reminder letters were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all” (1) to “quite a lot” (5), how much the reminder letters influenced their decisions to have mammograms. Furthermore, questions concerning interest in continued reminder letters or additional information about breast cancer screening were included. In the survey packages mailed to 6 family practices in the Hamilton, Ont, area (n = 172 women), we also included a reply sheet for respondents to indicate their willingness to be contacted about participation in local focus groups.

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 14.0, using a significance level of 0.05 (2-tailed) in all statistical tests. Univariate descriptive statistics, frequency distributions, and multivariate logistic regressions were used to describe the data and to examine potential correlates of letters’ influence on decisions to schedule or have mammograms.

Focus groups

We conducted 2 focus groups with a volunteer sample (n = 3 and n = 5) of survey respondents to explore some of the survey findings in greater depth. The interview guide solicited perspectives on knowledge of mammography, barriers and motivators to screening, impressions and responses to reminder letters, information needs, and preferred formats for information. The interviews were audiotaped with the written consent of participants.

Focus group audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and were read by 2 investigators to identify themes. Data were analyzed using template style, which involved the creation of a coding manual based on the interview questions and survey findings.

The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences/McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

Survey

The overall usable response rate was 55.7% (384 of 689), with an additional 4.9% (34 of 689) of women returning incomplete surveys. Characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 57.7 years (SD 6 years). Nonrespondents (n = 305) were slightly younger (mean age of 56.8 years) and significantly less likely to have ever had mammograms (64.3% vs 86.7%, P < .001), according to the external administrative databases (OBSP and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan databases) that were used to identify women eligible to receive reminder letters.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey participants: N = 384.

| CHARACTERISTIC | %* |

|---|---|

| Place of birth | |

| • Born in Canada | 77.1 |

| • Lived in Canada < 12 y | 21.6 |

| Marital status | |

| • Married or common law | 76.6 |

| • Widowed, separated, or divorced | 16.7 |

| • Single (never married) | 4.9 |

| Education | |

| • Some high school or elementary school | 20.3 |

| • High school graduate | 23.3 |

| • Community college graduate | 25.3 |

| • University graduate | 18.2 |

| Employment | |

| • Full-time | 37.8 |

| • Part-time | 20.1 |

| • Not employed | 39.8 |

| Income | |

| • Enough to easily meet needs | 19.5 |

| • Meets needs | 57.6 |

| • Not enough to meet needs | 19.3 |

| Self-rated health status | |

| • Excellent | 6.7 |

| • Very good | 39.3 |

| • Good | 32.0 |

| • Fair | 9.6 |

| • Poor | 1.0 |

Percentages might not add to 100% owing to rounding or missing data.

Most respondents (73.7%, 283 of 384) recalled receiving reminder letters and recalled the content of such letters. Nearly half of respondents (45.1%, 173 of 384) reported having had mammograms in the preceding 6 months, regardless of whether they recalled receiving reminder letters or not.

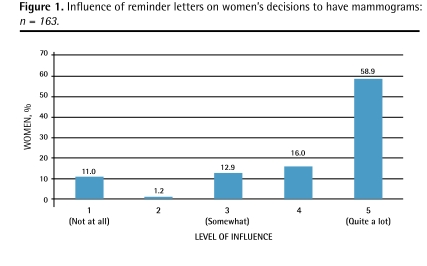

Among women who recalled receiving letters, 71.7% (203 of 283) of respondents planned to have mammograms, 50.9% (144 of 283) reported scheduling appointments, and 47.0% (133 of 283) had actually had mammograms. According to the external administrative data, 84.0% (121 of 144) of women who reported making appointments actually had mammograms within 4 months of the survey mailing. Three-quarters (74.8%, 122 of 163) of the respondents who recalled receiving letters and who either made appointments or had mammograms indicated that the reminder letter influenced their decision “a lot” or “quite a lot” (scores of 4 and 5 on the 5-point Likert scale; Figure 1). None of the variables examined in multivariate logistic regression (age, marital status, education, employment, self-reported health, place of birth) was significantly associated with the letters’ influence on decisions to schedule or have mammograms.

Figure 1.

Influence of reminder letters on women’s decisions to have mammograms: n = 163.

Most women (77.1%, 296 of 384) wanted to receive or continue to receive reminder letters for mammography. Almost a third of the women (28.9%, 111 of 384) wished to receive more information about mammography and breast cancer. Of these, 73.0% (81 of 111) preferred information in the form of a pamphlet and 21.6% (24 of 111) preferred a dedicated website.

Focus groups

Participants in the 2 focus groups (n = 3 and n = 5) indicated that they were receptive to reminder letters from their family physicians for screening mammography. Inclusion of the physician’s name on the letter was thought to be important, as was personalization of the letter with the patient’s name. Women felt that the use of a reminder letter reflected their doctors’ support of the screening test and concern for them. Most felt that the letters had clear messages and instructions. Participants indicated that women who had not been screened before might have different information needs. There was also interest in practical information, such as how to obtain transportation assistance.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the survey and the focus groups suggest that the participants had favourable attitudes toward the use of reminder letters to maximize screening mammography. Despite these favourable opinions, a substantial number of survey respondents did not remember receiving letters, although reminders were mailed to the same addresses as the questionnaires. This is consistent with findings from a survey exploring patient attitudes toward reminders for cholesterol screening, which also found that many respondents did not recall reminders or their contents.12

Not surprisingly, the personalized reminder letters from family physicians influenced women’s decisions to have mammograms and were seen as reflecting the physicians’ support for preventive screening. Previous studies found similar results but these were based on face-to-face counseling rather than mailed letters.10,11 Respondents who did not find the reminder letters helpful might have already scheduled appointments or decided to do so before receiving the letters. Alternatively, women who did not find the letters helpful might have been the same ones who did not get mammograms.

While there is substantial evidence supporting different reminder modalities to increase the use of preventive services, there are very few studies that have examined how such proactive interventions are viewed by the patients themselves.12,15–17 Some evidence suggests that attention to the format and content of patient reminder letters will likely further enhance their effectiveness.3,12 Ornstein et al conducted focus groups in which patients were asked to evaluate the reminder letter and other preventive services reminder materials used in an earlier study. The findings from these focus groups resulted in the development of a warmer, more personal letter, sent to patients at the time of their birthdays, that included a leaflet describing the rationale for preventive services and answering common questions about prevention.15 There is also some evidence suggesting that older patients are more likely to find reminders helpful18 and that stronger patient-provider relationships, with high levels of trust, are associated with improved adherence to recommended preventive services.19 It is also important to point out that the larger demonstration project of a reminder and recall system for preventive care services, on which our study was based, sent a second reminder that included patient education leaflets to eligible women who remained unscreened after the first letter. In our survey, however, only a random sample of women who received the first reminder letter was included.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our findings. First, the questionnaire might have biased the results, as it was developed by the investigators and was not assessed for validity or reliability beyond face validity. The substantial proportion of women who did not remember the reminder raises concerns about the credibility and accuracy of other responses. This was a self-administered cross-sectional survey, and the response rate, while low, is consistent with response rates for similar mailed surveys of patients in family practices.20,21

The reminder letters included a brief explanation of the rationale for screening mammography, and relatively few women were interested in additional information about mammograms. The focus group discussions revealed that women who had been screened, and therefore would have viewed videos or had the procedure explained to them before the test, felt they were adequately informed, but that women who had not yet been screened might benefit from additional information. Consequently, reminder letters should be tailored to women’s needs, and letters sent to women who are newly eligible for screening mammography should include additional educational resources.

Conclusion

The cumulative evidence around the use of reminder letters to increase the use of preventive services clearly establishes their effectiveness, and there is growing evidence that the patients welcome such letters. Furthermore, these reminders appear to be particularly effective when they originate from one’s own family physician, are personalized, and are coupled with relevant educational content. Eliciting patient feedback on reminder systems for preventive services can help ensure that features important to patients are included, thus further improving their acceptability and effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Primary Health Care Transition Fund.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

There is very good evidence that reminder letters increase the use of preventive services by patients, including the uptake of breast cancer screening.

Reminder letters are especially effective when they are personalized, come from the person’s family physician, and are linked to educational content.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Plusieurs données indiquent que les lettres de rappel augmentent l’utilisation par les patients des services préventifs, incluant le dépistage du cancer du sein.

Les lettres de rappel sont particulièrement efficaces quand elles sont personnalisées, proviennent du médecin de famille de la patiente et s’accompagnent d’un contenu informatif.

Footnotes

*Full text is available in English at www.cfp.ca.

Contributors

Drs Kaczorowski, Karwalajtys, Lohfeld, Roder, and Sebaldt and Ms Laryea and Ms Anderson contributed to concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparation of the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care . Screening for breast cancer. London, ON: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 1994. . Available from: www.ctfphc.org. Accessed 2009 Apr 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadden N, Doyle GP. Breast cancer screening in Canada: a review. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2005;56(5):271–5. Erratum in: Can Assoc Radiol J 2006;57(2):67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gøtzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2006;(4):CD001877. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jean S, Major D, Rochette L, Brisson J. Screening mammography participation and invitational strategy: the Quebec Breast Cancer Screening Program, 1998–2000. Chronic Dis Can. 2005;26(2–3):52–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Care Ontario . Breast screening. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2006. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/pcs/screening/breastscreening/. Accessed 2008 Apr 12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upshur R, Wang L, Maaten S, Leong A. Patterns of primary and secondary prevention. In: Jaakkimainen L, Upshur R, Klein-Geltnik JE, Leong A, Maaten SE, Wang L, editors. Primary care in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto, ON: Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iron K. Moving toward a better health data system for Ontario. ICES investigative report. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxwell CJ, Bancej CM, Snider J. Predictors of mammography use among Canadian women aged 50–69: findings from the 1996/97 National Population Health Survey. CMAJ. 2001;164(3):329–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonfill X, Marzo M, Pladevall M, Martí J, Emparanza JI. Strategies for increasing the participation of women in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2001;(1):CD002943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox SA, Murata PJ, Stein JA. The impact of physician compliance on screening mammography for older women. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox SA, Siu AL, Stein JA. The importance of physician communication on breast cancer screening of older women. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(18):2058–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ornstein SM, Musham C, Reid A, Jenkins RG, Zemp LD, Garr DR. Barriers to adherence to preventive services reminder letters: the patient’s perspective. J Fam Pract. 1993;36(2):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD. Methods in observational epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillman D. Mail and Internet surveys: the tailored design method. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ornstein SM, Musham C, Reid AO, Garr DR, Jenkins RG, Zemp LD. Improving a preventive services reminder system using feedback from focus groups. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):801–6. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson KK, Sebaldt RJ, Lohfeld L, Karwalajtys T, Ismaila AS, Goeree R, et al. Patient views on reminder letters for influenza vaccinations in an older primary care patient population: a mixed methods study. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(2):133–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03405461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karwalajtys T, Kaczorowski J, Lohfeld L, Laryea S, Anderson K, Roder S, et al. Acceptability of reminder letters for Papanicolaou tests: a survey of women from 23 family health networks in Ontario. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(10):829–34. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchinson HL, Norman LA. Compliance with influenza immunization: a survey of high-risk patients at a family medicine clinic. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(6):448–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):777–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodward CA, Ostbye T, Craighead J, Gold G, Wenghofer EF. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care in independent health facilities: developing and assessing a tool to enhance public accountability. Am J Med Qual. 2000;15(3):94–105. doi: 10.1177/106286060001500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisler JJ, Brown JB, Stewart M. Family physicians’ roles in cancer care. Survey of patients on a provincial cancer registry. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:889–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]