Abstract

The objective of the present study was to examine the effects of intermittent hypoxia (IH) and sustained hypoxia (SH) on hypoxia-evoked catecholamine (CA) secretion from chromaffin cells in neonatal rats and assess the underlying mechanism(s). Experiments were performed on rat pups exposed to either IH (15-s hypoxia/5-min normoxia; 8 h/day) or SH (hypobaric hypoxia, 0.4 atm) or normoxia (controls) from P0 to P5. IH treatment facilitated hypoxia-evoked CA secretion and elevations in the intracellular calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i) and these responses were attenuated, but not abolished, by treatments designed to eliminate Ca2+ flux into cells (Ca2+-free medium or Cd2+), indicating that intracellular Ca2+ stores were augmented by IH. Norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E) levels of adrenal medullae were elevated in IH-treated pups. IH treatment increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in adrenal medullae and antioxidant treatment prevented IH-induced facilitation of CA secretion, elevations in [Ca2+]i by hypoxia, and the up-regulation of NE and E. The effects of neonatal IH treatment on hypoxia-induced CA secretion and elevation in [Ca2+]i, CA, and ROS levels persisted in rats reared under normoxia for >30 days. In striking contrast, chromaffin cells from SH-treated animals exhibited attenuated hypoxia-evoked CA secretion. In SH-treated cells hypoxia-evoked elevations in [Ca2+]i, NE and E contents, and ROS levels were comparable with controls. These observations demonstrate that: 1) neonatal IH and SH evoke opposite effects on hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells, 2) ROS signaling mediates the faciltatory effects of IH, and 3) the effects of neonatal IH on chromaffin cells persist into adult life.

INTRODUCTION

Catecholamine (CA) secretion from the adrenal medulla is critical for maintaining homeostasis under a variety of stress conditions including hypoxia (Lagercrantz and Bistoletti 1977; Seidler and Slotkin 1985). In adult animals, hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells is neurogenic and requires activation of the sympathetic nervous system (Seidler and Slotkin 1986; Yokotani et al. 2002). In neonates the sympathetic nervous system is not well developed (Seidler and Slotkin 1985). In this case, hypoxia still evokes CA secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells by directly affecting their excitability and elevating intracellular calcium ion concentration ( [Ca2+]i; Takeuchi et al. 2001; Thompson et al. 1997). These studies demonstrate that neonatal chromaffin cells have the ability to sense acute hypoxia similar to the glomus cells of the carotid bodies of adult mammals.

Chronic perturbations in environmental O2 profoundly influence carotid body sensory response to acute hypoxia. For instance, prolonged exposure to either sustained hypoxia (SH; He et al. 2006; Nielsen et al. 1988) or intermittent hypoxia (IH; Peng and Prabhakar 2004; Rey et al. 2004) augment the carotid body response to subsequent exposures to acute hypoxia. In the present study we examined whether exposure of neonatal rat pups to either IH or SH also augment hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells and, if so, by what mechanism(s). This possibility was examined on rat pups exposed to IH or SH from newborn to postnatal day 5 (P0–P5). Our results showed that neonatal IH augments, whereas SH attenuates hypoxia-evoked CA secretion. The data further showed that reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling is critical for mediating the effects of IH but not by SH. Remarkably, the effects of neonatal IH on the hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells persisted into adult life.

METHODS

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. Experiments were performed on neonatal Sprague–Dawley rats pups (P0–P35).

Exposure to IH and SH

Rat pups (P0) along with their mothers were exposed to IH (15-s 5% O2 followed by 5-min 21% O2; 8 h/day) for 5 days (P0–P5; between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm) as described previously (Pawar et al. 2008). Briefly, rat pups along with their mother were housed in feeding cages and placed in a chamber designed for exposure to IH. The animals were unrestrained, freely mobile, and fed without restriction. The chamber was flushed with alternating cycles of nitrogen gas and room air. Inspired O2 levels reached a nadir of 5% O2 during hypoxia. O2 and CO2 levels in the chamber were continuously monitored and ambient CO2 levels were maintained between 0.2 and 0.5%. Control experiments were performed on age-matched rat pups exposed to normoxia. In the protocols involving antioxidant treatment, rat pups were given manganese (III) tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin pentachloride (MnTMPyP; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA; 5 mg·kg−1·day−1, administered intraperitoneally [ip]), a membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic or N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; 800 mg·kg−1·day−1, ip), every day prior to placing rats in the IH chamber. Rat pups treated with vehicle (saline) served as controls. To determine the effects of SH, rat pups along with their mother were exposed to hypobaric hypoxia (0.4 atm) for either 24 h or 5 days as described previously (Kumar et al. 2006). Acute experiments were performed on anesthetized pups (urethane 1.2 g·kg−1, ip) 6–10 h following either IH, SH, or normoxia.

Preparation of chromaffin cells and cell culture

Adrenal glands were harvested from IH, SH, and control rat pups anesthetized with urethane (1.2 g·kg−1, ip). The adrenal cortex was removed and the medulla was cut into small pieces. Chromaffin cells were enzymatically dissociated using a mixture of collagenase P (2 mg/ml; Roche), DNase (25 μg/ml; Sigma), and bovine serum albumin (3 mg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by a 15-min digestion in 0.03% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) and DNase 50 μg/ml (Sigma). Cells were centrifuged at 200 g for 15 min at 4°C and were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips (type VII; Sigma) and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 12–24 h. The growth medium consisted of F-12 K medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine cocktail (Invitrogen).

Amperometry

Catecholamine secretion from chromaffin cells was monitored by amperometry using carbon-fiber electrodes as described previously (Grabner et al. 2006). The electrode was held at +700 mV versus a ground electrode using an NPI VA-10 amplifier to oxidize catecholamine transmitter. The amperometric signal was low-pass filtered at 2 kHz (eight-pole Bessel; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and sampled into a computer at 10 kHz using a 16-bit A/D converter (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Records with root-mean-square (RMS) noise >2 pA were not analyzed. Amperometric spike features, quantal size, and kinetic parameters were analyzed using a series of macros written in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics) kindly supplied by Dr. Eugene Mosharov. The detection threshold for an event was set at four to five times the RMS noise and the spikes were automatically detected. The area under individual amperometric spikes is equal to the charge (pC) per release event, referred to as Q. The number of oxidized neurotransmitter molecules (N) was calculated using the Faraday equation, N = Q/ne, with n = 2 electrons per oxidized molecule of transmitter and where e is the elemental charge (1.603 × 10−19 coulombs). Because the number of events varied considerably from cell to cell, the data from each cell were averaged to provide a single number for the overall statistic using the technique described by Colliver et al. (2000).

Recording solutions and stimulation protocols

Amperometric recordings were made from adherent cells that were under constant perfusion (flow rate of about 1.0 ml/min: chamber volume ≃ 80 μl). All experiments were performed at ambient temperature (23 ± 2°C), and the solutions had the following composition (in mM): 1.26 CaCl2, 0.49 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.4 MgSO4·7H2O, 5.33 KCl, 0.441 KH2PO4, 137.93 NaCl, 0.34 Na2HPO4·7H2O, 5.56 dextrose, and 20 Hepes (pH 7.35 and 300 mOsm). Normoxic solutions were equilibrated with room air (Po2 ≃ 146 mmHg). For challenging with hypoxia, solutions were degassed and equilibrated with appropriate gas mixtures that resulted in final medium Po2 values of 30, 60, and 100 mmHg as measured by blood gas analyzer. Ca2+-free solutions contained 0.5 mM EGTA.

Measurements of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was monitored in chromaffin cells as described previously (Xie et al. 2004). Briefly, chromaffin cells were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2 μM fura-2 AM and 1 mg/ml albumin for 30 min and washed in a fura-2-free solution for 30 min at 37°C. The coverslip was transferred to an experimental chamber for recording. Background fluorescence at 340- and 380-nm wavelengths were obtained using an area of the coverslip devoid of cells. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. On each coverslip, four to eight chromaffin cells were selected and individually imaged. Image pairs (one at 340 and the other at 380 nm) were obtained every 2 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the individual wavelengths and the 340-nm image was divided by the 380-nm image to provide a ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i by comparing data to fura-2 calibration curves made in vitro by adding fura-2 (50 μM free acid) to solutions that contained known concentrations of calcium (0–2,000 nM). The recording chamber was continually perfused with fresh solution from gravity-fed reservoirs.

Measurement of catecholamine content

Experiments were performed on freshly harvested adrenal medullae from anesthetized rats. Catecholamines were extracted with 0.1 N HClO4 containing 10 mM EDTA-Na2 and assayed by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD) as previously described (Kumar et al. 2006). Norepinephrine and epinephrine contents were expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein.

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA)

Adrenal medullary tissue was homogenized in 10 volumes of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C and centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C. MDA levels were analyzed in supernatants as previously described (Peng et al. 2006) and expressed as nanomoles of MDA formed per milligram of protein.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses between experimental groups are presented as means ± SE and Student's t-test was used for statistical comparisons between two groups. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

IH facilitates hypoxia-evoked CA secretion

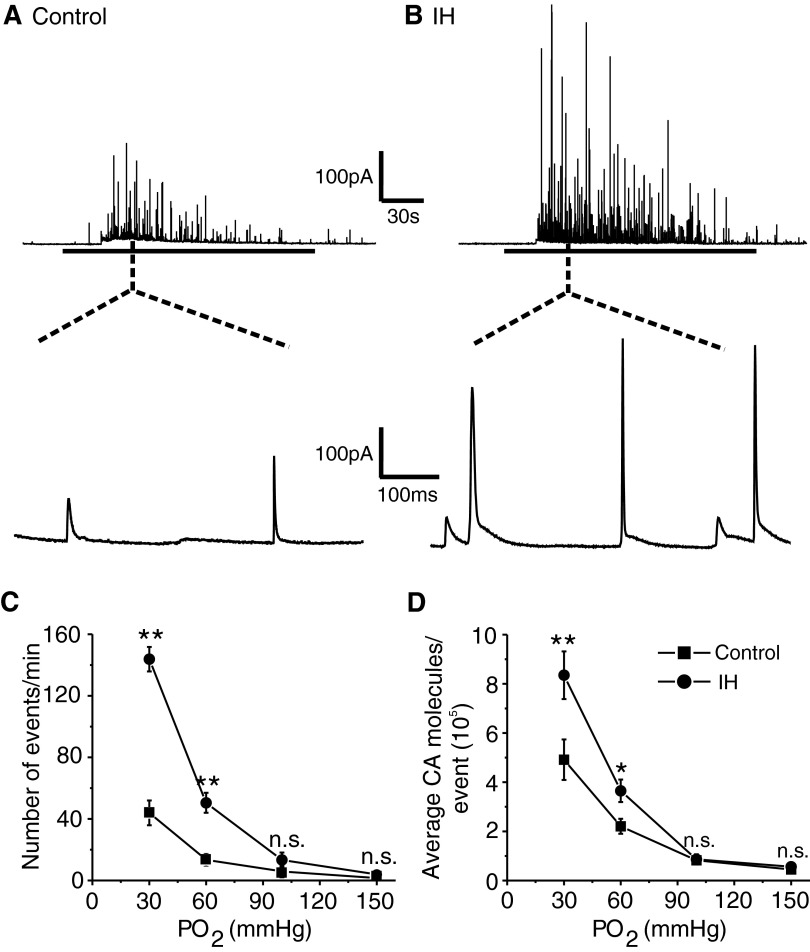

Acute hypoxia-evoked robust CA secretion from control and IH-treated chromaffin cells and the secretory response was greater in IH-treated cells than that in controls (Fig. 1, A and B). Averaging the data from many cells showed that the number of secretory events as well as the amount of CA released per event evoked by moderate (Po2 ≃ 60 mmHg) and severe (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) hypoxia were significantly higher in IH compared with control cells (P < 0.001; Fig. 1, C and D). Furthermore, a larger percentage of cells from IH-treated pups responded to hypoxia than cells derived from control pups (control = 17 of 23 cells = 74% vs. IH = 20 of 22 cells = 90%).

FIG. 1.

Effects of intermittent hypoxia (IH) on hypoxia –evoked catecholamine (CA) secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells. A and B, top panels: examples of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cell derived from postnatal day 5 (P5) rats reared under normoxia (control) or IH. Horizontal black bar represents the duration of the hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg). Bottom panels: expanded view of the secretory events during hypoxia. The dotted lines indicate the segment of the tracing from which expanded view was chosen. C and D: average data on the effects of graded hypoxia. C: the number of secretory events/min. D: the average CA molecules released/event. Po2, partial pressure of oxygen (mmHg) in the superfusing medium. Data shown are means ± SE. Control = 17 cells, IH = 20 cells obtained from 3 different litters in each group. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

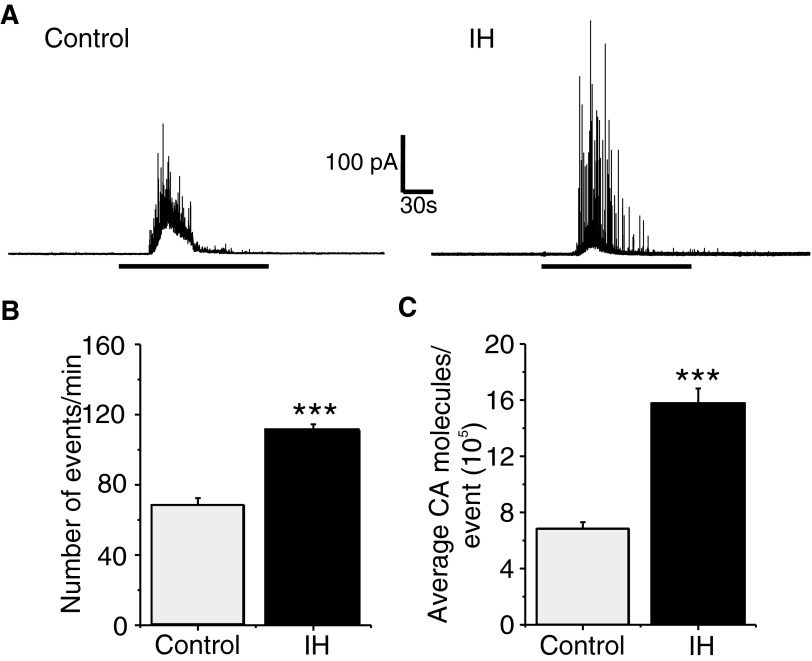

To determine whether the effects of IH were selective to the hypoxic stimulus, CA secretion by a depolarizing stimulus (40 mM K+) were determined. CA secretion evoked by K+ was significantly greater in IH than from control cells, arising from increases both in the number of secretory events and in the amount of CA released per secretory event (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of IH on K+-evoked CA secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells. A: examples of K+-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cell derived from P5 rats reared under normoxia (Control) or IH. The horizontal black bars represent the duration of K+ (40 mM KCl) challenge. B and C: average data of the effects of K+. B: the number of secretory events/min. C: average CA molecules released/event. Data shown are means ± SE. Control = 16; IH = 20 cells obtained from 3 different litters in each group. ***P < 0.0001.

The above-cited results showed that IH increases the amount of CA released per secretory event, which could be due to an increase in catecholamine content or number of vesicles undergoing fusion before exocytosis (i.e., compound exocytosis). To test the latter possibility, CA content of adrenal medullae was determined from control and IH-treated rat pups. Norepinephrine and epinephrine contents were significantly elevated in IH-treated adrenal medullae compared with controls (norepinephrine content: Control = 19.3 ± 1.4 vs. IH 49 ± 3.7 nmol/mg protein; epinephrine content: Control = 170 ± 14 vs. IH = 373 ± 11 nmol/mg protein; P < 0.001; n = 6 pups each).

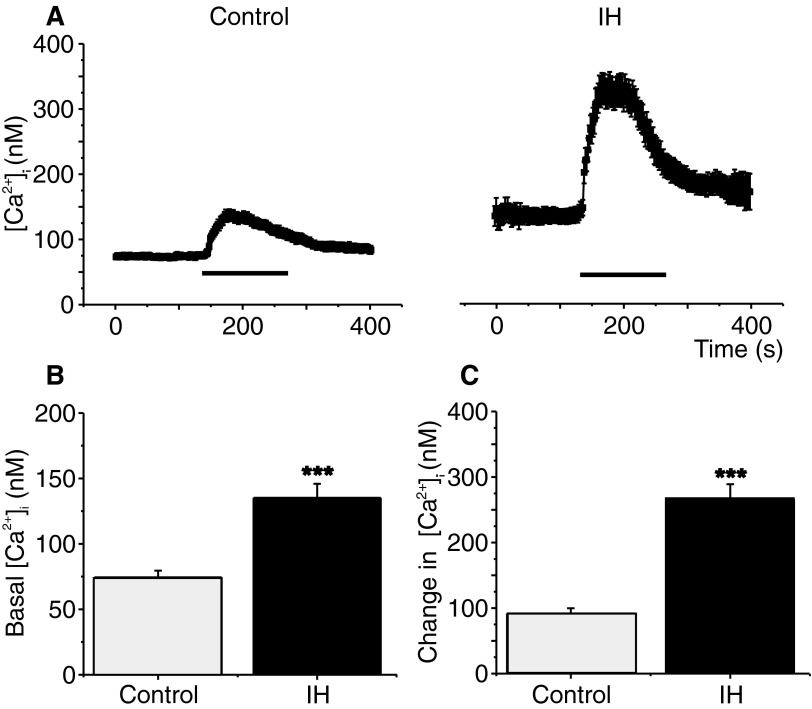

Effects of IH on hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i in chromaffin cells

In neonatal chromaffin cells, hypoxia-evoked CA secretion requires elevation of [Ca2+]i (Inoue et al. 1998; Takeuchi et al. 2001). Comparison of [Ca2+]i responses revealed both the baseline [Ca2+]i and the magnitude of hypoxia-induced elevation in [Ca2+]i were significantly higher in IH-treated cells than in the controls (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effects of IH on hypoxia-induced intracellular calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i) changes in neonatal chromaffin cells. A: mean [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) determined every 2 s in individual chromaffin cells from P5 rats reared in normoxia (Control) or IH. Horizontal black bars represent the duration of the hypoxic challenge. B and C: average data of basal (B) and hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i changes (C) in chromaffin cells from control and IH-treated rat pups. Data presented are means ± SE from 33 and 38 cells in Control and IH, respectively. The cells were obtained from 3 different litters in each group. ***P < 0.0001.

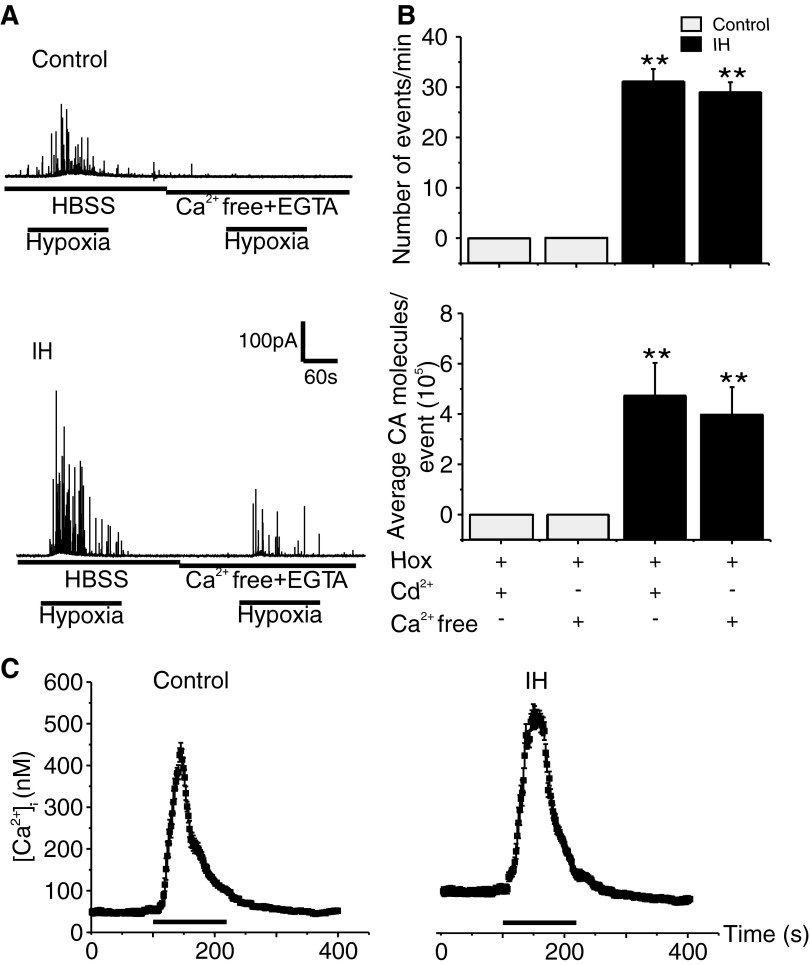

To assess the contribution of extracellular Ca2+ flux, hypoxia-evoked CA secretion was monitored in the presence of Ca2+-free medium (i.e., medium with zero calcium and 0.5 mM of EGTA). As shown in Fig. 4, in control cells hypoxia-evoked CA secretion was suppressed in Ca2+-free medium, whereas small but significant CA secretion could still be elicited in IH-treated cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Similar results were also obtained with medium containing 300 μM Cd2+, a broad spectrum blocker of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Fig. 4B). The residual CA secretion in the absence of Ca2+ flux seen in IH-treated cells might be due to the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+. To assess this possibility, we examined the effects of 10 mM caffeine, which mobilizes Ca2+ stores from sarcoplasmic reticulum, on [Ca2+]i in control and IH-treated cells. The elevations in [Ca2+]i by caffeine were slightly but significantly higher in IH compared with control cells (Fig. 4C; Control = +380 ± 8 vs. IH = +426 ± 7 nM; an increase of ∼46 nM in IH cells; Control vs. IH; P < 0.05; n = 9 and 11 cells for Control and IH, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Contribution of Ca2+ flux on hypoxia-evoked CA secretion in control and IH-treated chromaffin cells. A: representative examples showing the effect of Ca2+-free medium (HBSS with zero Ca2+ + 0.5 mM EGTA) on hypoxia-induced CA secretion from Control and IH-treated chromaffin cells. HBSS, Hank's balanced salt solution. The horizontal black bars represent the duration of the hypoxic challenge (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg). B: average data of secretory events/min and average CA molecules released/event. Hox, hypoxia; Cd2+ (300 μM); Ca2+-free, Ca2+-free medium. Data shown are means ± SE. Cd2+: Control = 9; IH = 11cells; Ca2+-free solution: Control = 9 and IH = 12 cells obtained from 3 different litters in each group. **P < 0.001. C: effects of caffeine on [Ca2+]i in control and IH-treated cells. Traces represent mean [Ca2+]i responses to caffeine ((10 mM) determined every 2 s from individual chromaffin cells from P5 rats reared in normoxia (Control; n = 9 cells) or IH (n = 11cells). Horizontal black bars represent the duration of the caffeine challenge.

ROS signaling mediates chromaffin cell responses to IH

Previous studies have shown that reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate cellular responses to IH (Prabhakar et al. 2007). To determine whether ROS do play a role in chromaffin cell responses to IH, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in adrenal medullae were monitored as an index of ROS generation (Peng et al. 2006; Ramanathan et al. 2005). The MDA levels were elevated by 60% in adrenal medullae from IH compared with control pups (P < 0.001; Fig. 5A) and this response was prevented by systemic administration of MnTMPyP, a cell-permeable antioxidant.

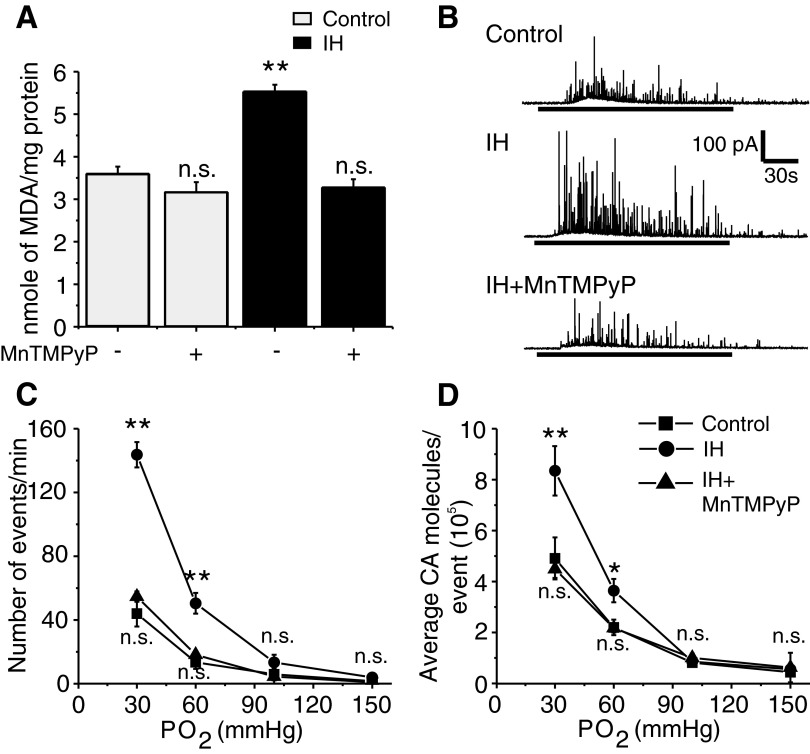

FIG. 5.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate IH-evoked facilitation of hypoxia-induced CA secretion. A: malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined as an index of ROS levels from adrenal medullae from rat pups reared under normoxia (Control) or IH treated with antioxidant manganese (III) tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin pentachloride (MnTMPyP, 5 mg·kg−1·day−1, administered intraperitoneally from P0–P5 denoted by +) or vehicle (denoted by −). Data presented are means ± SE from 6 rat pups derived from 3 different litters in each group. **P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05). B: representative examples of hypoxia-induced CA secretion (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg; at horizontal black bars) in control, IH, and IH + MnTMPyP-treated chromaffin cells. C and D: average data on the effects of graded hypoxia. C: the number of secretory events/min. D: the average CA molecules released per event. Po2 = partial pressure of O2 in mmHg. Data shown are means ± SE. Control = 17; IH = 20; IH + MnTMPyP = 14 cells from 3 different litters in each group. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

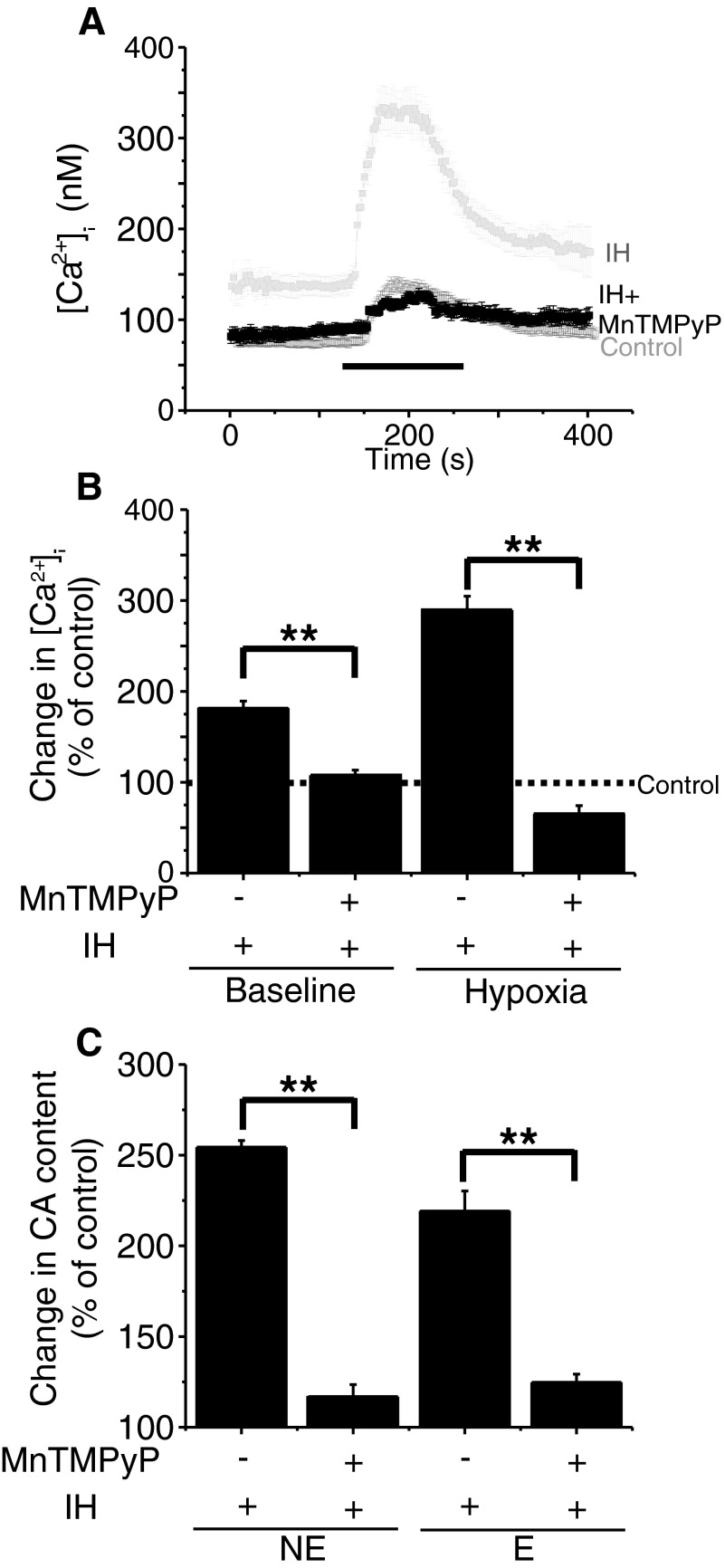

To determine whether ROS contribute to chromaffin cell responses to IH, rat pups were treated with MnTMPyP every day for 5 days prior to subjecting them to IH conditions. As shown in Fig. 5B, MnTMPyP treatment completely prevented IH-evoked facilitation of hypoxia-induced CA secretion in terms of both the number of secretory events and the amount of CA secreted per event. The remaining secretory response to hypoxia was comparable with that of control cells (Fig. 5C). Also, MnTMPyP prevented IH-induced facilitation of the [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia as well as the elevated norepinephrine and epinephrine contents of adrenal medullae (Fig. 6). Similar results were also obtained with NAC (800 mg·kg−1·day−1, ip for 5days), another structurally and functionally distinct antioxidant. Thus in cells derived from IH pups treated with NAC, the number of secretory events/min and average CA molecules secreted per event (×105) during the hypoxic challenge were 53 ± 4.2/min and 4.6 ± 0.3/event, respectively (n = 12), which were similar to hypoxia-evoked secretory response in control cells [the number of secretory events/min = 43 ± 8; CA molecules/event (×105) = 5 ± 0.8; n = 17; P > 0.05].

FIG. 6.

Antioxidant treatment prevents IH-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i and CA contents. A: traces of mean [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) determined every 2 s in individual chromaffin cells from control and IH or IH + MnTMPyP (antioxidant) treated chromaffin cells. Horizontal black bars represent the duration of the hypoxic challenge. The data presented for Control and IH were the same as in Fig. 3. B: average data of basal and hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i changes in chromaffin cells from IH and IH + MnTMPyP-treated rat pups presented as percentage of control cells (Control = 100%). The data presented are means ± SE. Control = 33, IH = 38, and IH + MnTMPyP = 34 cells from 3 different litters in each group. **P < 0.001. C: average results showing the effects of antioxidant (MnTMPyP) treatment on IH-evoked up-regulation of norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E) contents of adrenal medullae. CA contents were presented as percentage of controls (normoxia; Control = 100%). Data presented are means ± SE from 6 rat pups from 3 different litters in each group. **P < 0.001.

Effects of neonatal IH on chromaffin cells persist into adult life

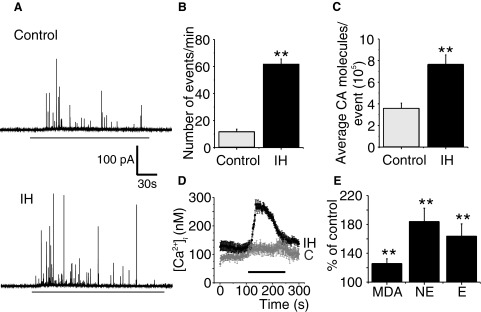

The effects of IH on carotid body response to hypoxia in adult rats could be completely reversed following re-exposing IH-treated rats to normoxia (Peng et al. 2003). To determine whether the effects of neonatal IH could be reversed following re-exposure to normoxia, rat pups were exposed to IH from P0 to P5 and were then reared under normoxia for 30 days. Subsequently, chromaffin cell responses to hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) were determined in P35 rats. Control experiments were performed on age-matched rats that were not exposed to neonatal IH. In control P35 rats, only 20% of cells (6 of 30) responded to hypoxia with increased CA secretion, whereas in rats exposed to neonatal IH, nearly 45% of cells (11 of 24) responded to hypoxia. The magnitude of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion (the number of secretory events as well as the amount of CA secreted per event) and elevations in [Ca2+]i were significantly greater in neonatal IH-treated chromaffin cells compared with corresponding age-matched controls (P < 0.001;Fig. 7, A–D). In addition, the levels of MDA as well as norepinephrine and epinephrine in adrenal medullae were also significantly higher in P35 rats that were exposed to neonatal IH compared with controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 7E).

FIG. 7.

The effects of neonatal IH persist in P35 rats. A: examples of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells harvested from P35 rat reared under normoxia (control) and age-matched rat exposed to neonatal IH from P0 to P5. Horizontal black bar represents the duration of hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg). B and C: average data on the effects of hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) on the number of secretory events/min and average CA molecules released/event. Data presented are means ± SE from n = 30 control cells and n = 24 cells from neonatal IH-treated rats derived from 3 different litters. D: effect of neonatal IH on hypoxia-induced changes in [Ca2+]i changes in chromaffin cells from P35 rats. Traces represent mean [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg) determined every 2 s in individual chromaffin cells from P35 rats reared in normoxia (C; n = 11cells) or neonatal IH (n = 15 cells). Horizontal black bar represent the duration of the hypoxic challenge. E: effect of neonatal IH exposure on malondialdehyde (MDA), norepinephrine (NE), and epinephrine (E) levels of adrenal medullae from P35 rats. Results are presented as percentage of controls, i.e., P35 rats reared under normoxia (control = 100%). Data presented are means ± SE from 6 rats in each group. **P < 0.001.

SH attenuates hypoxia-evoked CA secretion

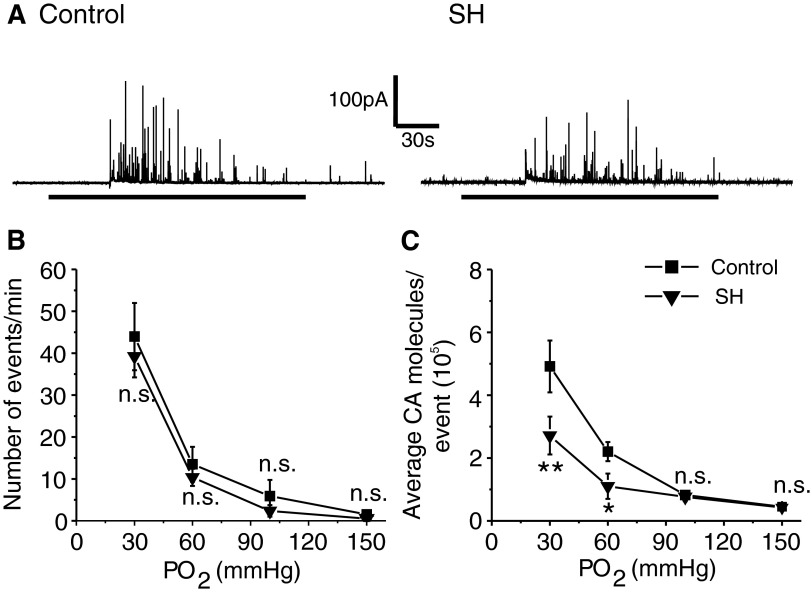

To assess the effects of SH, rat pups were exposed to hypobaric hypoxia (0.4 atm) for either 24 h (P0–P1) or 5 days (P0–P5), after which the effects of acute hypoxia on CA secretion from chromaffin cell were determined. Control experiments were performed on age-matched pups reared under normoxia. Exposing rat pups to 24 h of SH had no significant effect on hypoxia-evoked CA secretion compared with controls [Number of events/min: Control = 44 ± 6 vs. SH = 48 ± 9; average CA molecules/event (105); Control = 5 ± 0.9 vs. SH = 5.8 ± 1; SH vs. Control: P > 0.05; n = 12 cells each]. On the other hand, after 5 days of SH, hypoxia-evoked CA secretion was reduced, which primarily arose from a decrease in the amount of CA released per secretory event (P < 0.01; Fig. 8). Furthermore, the number of cells responding to hypoxia decreased in pups treated with 5 days of SH (Control = 17 of 23 cells = 74% vs. SH = 18 of 32 cells = 56%). Likewise, SH treatment attenuated K+-evoked CA secretion, which also arose from a reduced amount of CA released per secretory event (SH = 5 ± 0.2 vs. Control = 7 ± 0.5 ×105 CA molecules per event; P < 0.01; n = 20 and 16 cells for SH and control, respectively). The levels of basal as well as the magnitude of hypoxia-induced elevation in [Ca2+]i were comparable between SH and control cells (P > 0.05). Furthermore, SH had no significant effect on norepinephrine, epinephrine, and MDA levels of the adrenal medullae compared with controls (P > 0.05; control and SH, n = 6 adrenal medulla in each group).

FIG. 8.

Effects of sustained hypoxia (SH) on hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells. A and B: examples of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells from P5 rats reared under normoxia (control) or SH (5days). Horizontal black bars represent the duration of hypoxic challenge (Po2 ≃ 30 mmHg). C and D: average data of the effects of graded hypoxia: the number of secretory events/min (C) and average CA molecules released per event (D). Po2 = partial pressure of oxygen (mmHg) of the superfusing medium. Data shown are means ± SE from 17 cells (control) and 18 cells (SH) obtained from 3 different litters in each group. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Major findings of the present study were: 1) exposure of neonatal rat pups to IH for periods as short as 5 days led to pronounced facilitation of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion, elevation of [Ca2+]i in chromaffin cells, and up-regulation of CA content in the adrenal medullae; 2) IH increased ROS levels in adrenal medullae and antioxidant treatment prevented IH-evoked facilitation of CA secretion, changes in [Ca2+]i, and up-regulation of CA content; 3) the effects of neonatal IH on chromaffin cells persisted into adult life; and 4) SH attenuated hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from chromaffin cells and this effect was associated with no significant changes in hypoxia-induced elevation in [Ca2+]i, CA content, and ROS levels in adrenal medulla.

Consistent with the previous studies on the carotid body (Pawar et al. 2008; Peng and Prabhakar 2004), we also found that IH enhances hypoxic sensing of chromaffin cells from neonatal rat pups. A previous study reported that prior exposure to IH appreciably facilitates hypoxia-evoked CA efflux from adult rat adrenal medulla (Kumar et al. 2006). However, it was not clear whether this IH-induced CA efflux was due to augmented CA secretion or/and inhibition of CA uptake. Using the amperometric approach, the current study demonstrates that IH indeed facilitates CA secretion by hypoxia, which was due not only to enhanced number of secretory events but also to the elevated neurotransmitter content of each event.

The following observations demonstrate that ROS signaling mediates the facilitatory effects of IH on neonatal chromaffin cells. First, IH increased ROS in adrenal medullae as evidenced by elevated MDA levels. Second, antioxidants prevented IH-evoked facilitation of CA secretion by hypoxia. Previous studies suggest that depolarization (Garcia-Fernandez et al. 2007; Mojet et al. 1997; Thompson et al. 1997) and subsequent activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and the ensuing elevations in [Ca2+]i (Takeuchi et al. 2001) are critical for hypoxia-induced CA secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells. Our findings that hypoxia-induced elevations in [Ca2+]i were more pronounced in IH-treated cells than in control cells and that antioxidant prevented this response suggests that ROS acts to increase Ca2+ signaling. Observations with Ca2+-free medium and Cd2+ suggest that facilitation of CA secretion by IH requires Ca2+ flux and to a smaller extent mobilization of intracellular Ca2+. Studies with caffeine partly support the latter possibility. A recent study suggests that T-type Ca2+ channels play an important role in hypoxia-evoked CA secretion in neonatal rat chromaffin cells (Levitsky and Lopez-Barneo 2007), which can be modulated by changes in the redox state, as shown elsewhere in the nervous system (Joksovic et al. 2006). Prolonged hypoxia up-regulates T-type Ca2+ channels in neonatal chromaffin cells (Carabelli et al. 2009); the newly expressed T-type channels are thought to contribute to elevated resting [Ca2+]i levels and cell depolarization by being partly open at rest (a “window current”). A similar mechanism may be operating in our study as resting [Ca2+]i levels were elevated in the IH-treated chromaffin cells. Further studies, however, are needed to determine whether IH affects Ca2+ channels, especially the T-type as well as the mechanisms by which ROS mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in IH-treated cells. It is interesting that despite the elevated basal [Ca2+]i levels, resting CA secretion was not augmented in IH-treated cells. To evoke CA secretion, [Ca2+]i has to be elevated near the secretory vesicles. The imaging technique used in the current study is inadequate to provide spatial resolution of [Ca2+]i changes near the secretory vesicles. Therefore it is conceivable that the absence of enhanced basal CA secretion in IH-treated cells is due to the lack of an increase in [Ca2+]i near the site of secretion.

Unlike adrenal medullae from adult rats (Hui et al. 2003), IH increased both norepinephrine and epinephrine contents in neonatal adrenal medullae. We believe that the elevated CA content represents increased synthesis because IH activates tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in CA synthesis (Kumar et al. 2003). The observation that antioxidant treatment prevents IH-evoked up-regulation of CA suggests that in addition to Ca2+ signaling, ROS-mediated activation of CA synthesis also contributes to facilitation of CA secretion by hypoxia.

An intriguing finding of the present study was that although IH was given for only 5 days in neonatal life, its effects persisted even into adult life. We believe that the long-lasting effects of neonatal IH are due to elevations of ROS levels, which might be attributed to long-term changes in genes associated with the maintenance of cellular redox state. It is being increasingly appreciated that epigenetic regulation via DNA methylation and histone modifications, especially during development, leads to long-term changes in gene expression (Feinberg 2007). The sustained elevations in ROS levels could conceivably be due to epigenetic regulation of genes encoding either pro- and/or antioxidant enzyme(s) by IH, a possibility that requires further study.

Prolonged exposure to SH facilitates hypoxia-evoked CA secretion in rat PC12 cells (Taylor and Peers 1999) and elevates ROS levels in cell cultures (Bell et al. 2007; Guzy et al. 2005). Based on these studies, we anticipated that SH would also facilitate hypoxia-induced CA secretion from neonatal chromaffin cells via ROS signaling. Contrary to our expectation, SH attenuated hypoxia-evoked CA secretion due to a reduction in the amount of CA released per secretory event. The effects of SH on CA secretion were associated with un-altered ROS levels in adrenal medullae. The differences between our results and those reported previously on cell cultures (Bell et al. 2007; Guzy et al. 2005; Taylor and Peers 1999) could arise from differences in the experimental preparations such as cell culture versus intact animals as well as propagating phenotype of cells used in earlier studies versus the nonpropagating nature of native chromaffin cells used in this study. Hypobaric hypoxia can lower the metabolism and body temperature in rat pups (Baig and Joseph 2008). Alternatively, the reduced CA secretion might be secondary to the effects of SH on body metabolism, resulting in reduced tyrosine hydroxylase activity leading to decreased CA synthesis. The attenuated secretory response to hypoxia appears unlikely due to changes in CA synthesis because neither norepinephrine nor epinephrine levels were altered in SH-treated compared with control adrenal medullae. It is possible that reduced emptying of the secretory vesicles might account for the attenuated CA release. In chromaffin cells, weak stimulation leading to modest elevation in [Ca2+]i tends to promote only a partial release of the vesicular CA content via a kiss-and-run mechanism, whereas stronger stimuli resulting in robust elevation in [Ca2+]i either evokes a more complete emptying of the vesicle content or, alternatively, causes vesicles to undergo full fusion (Elhamdani et al. 2001, 2006). The absence of facilitation of hypoxia-evoked CA secretion might in part be due to the inability of SH to augment hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i response, which is in part attributed to the absence of enhanced ROS generation by SH.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that exposing neonatal rat pups to IH facilitates, whereas to SH attenuates, CA secretion by hypoxia. The effects of neonatal IH persisted even into adult life. What might be the significance of long-lasting up-regulation of the hypoxic sensitivity of chromaffin cells by neonatal IH? Between 70 and 90% of prematurely born infants experience IH because of recurrent apneas (Stokowski 2005), with each episode lasting two breaths or longer. It is likely that premature infants experiencing IH as a consequence of recurrent apneas are vulnerable to develop cardiovascular morbidities in adult life because of the augmented CA secretion by hypoxia, which is a common stress that is encountered under a variety of physiological and pathophysiological situations.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-76537, HL-90554, and HL-86493 to N. R. Prabhakar; HL-089616 to G. K. Kumar; and GM-081809 and a Philip Morris International grant to A. Fox.

REFERENCES

- Baig 2008.Baig MS, Joseph V. Age specific effect of MK-801 on hypoxic body temperature regulation in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 160: 181–186, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell 2007.Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol 177: 1029–1036, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli 2007.Carabelli V, Marcantoni A, Comunanza V, de Luca A, Diaz J, Borges R, Carbone E. Chronic hypoxia up-regulates alpha1H T-type channels and low-threshold catecholamine secretion in rat chromaffin cells. J Physiol 584: 149–165, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colliver 2000.Colliver TL, Pyott SJ, Achalabun M, Ewing AG. VMAT-mediated changes in quantal size and vesicular volume. J Neurosci 20: 5276–5282, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhamdani 2006.Elhamdani A, Azizi F, Artalejo CR. Double patch clamp reveals that transient fusion (kiss-and-run) is a major mechanism of secretion in calf adrenal chromaffin cells: high calcium shifts the mechanism from kiss-and-run to complete fusion. J Neurosci 26: 3030–3036, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhamdani 2001.Elhamdani A, Palfrey HC, Artalejo CR. Quantal size is dependent on stimulation frequency and calcium entry in calf chromaffin cells. Neuron 31: 819–830, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg 2007.Feinberg AP Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature 447: 433–440, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fernandez 2007.Garcia-Fernandez M, Mejias R, Lopez-Barneo J. Developmental changes of chromaffin cell secretory response to hypoxia studied in thin adrenal slices. Pflügers Arch 454: 93–100, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner 2006.Grabner CP, Price SD, Lysakowski A, Cahill AL, Fox AP. Regulation of large dense-core vesicle volume and neurotransmitter content mediated by adaptor protein 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10035–10040, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy 2005.Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, Simon MC, Hammerling U, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab 1: 401–408, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He 2006.He L, Chen J, Dinger B, Stensaas L, Fidone S. Effect of chronic hypoxia on purinergic synaptic transmission in rat carotid body. J Appl Physiol 100: 157–162, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui 2003.Hui AS, Striet JB, Gudelsky G, Soukhova GK, Gozal E, Beitner-Johnson D, Guo SZ, Sachleben LR Jr, Haycock JW, Gozal D, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Regulation of catecholamines by sustained and intermittent hypoxia in neuroendocrine cells and sympathetic neurons. Hypertension 42: 1130–1136, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue 1998.Inoue M, Fujishiro N, Imanaga I. Hypoxia and cyanide induce depolarization and catecholamine release in dispersed guinea-pig chromaffin cells. J Physiol 507: 807–818, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksovic 2006.Joksovic PM, Nelson MT, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Patel MK, Perez-Reyes E, Campbell KP, Chen CC, Todorovic SM. CaV3.2 is the major molecular substrate for redox regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in the rat and mouse thalamus. J Physiol 574: 415–430, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar 2003.Kumar GK, Kim DK, Lee MS, Ramachandran R, Prabhakar NR. Activation of tyrosine hydroxylase by intermittent hypoxia: involvement of serine phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol 95: 536–544, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar 2006.Kumar GK, Rai V, Sharma SD, Ramakrishnan DP, Peng YJ, Souvannakitti D, Prabhakar NR. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces hypoxia-evoked catecholamine efflux in adult rat adrenal medulla via oxidative stress. J Physiol 575: 229–239, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz 1977.Lagercrantz H, Bistoletti P. Catecholamine release in the newborn infant at birth. Pediatr Res 11: 889–893, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky 1997.Levitsky KL, Lopez-Barneo J. Developmental change of T-type Ca2+ channel expression and its role in rat chromaffin cell responsiveness to acute hypoxia. J Physiol (March 9, 2009). doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mojet 1997.Mojet MH, Mills E, Duchen MR. Hypoxia-induced catecholamine secretion in isolated newborn rat adrenal chromaffin cells is mimicked by inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. J Physiol 504: 175–189, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen 1988.Nielsen AM, Bisgard GE, Vidruk EH. Carotid chemoreceptor activity during acute and sustained hypoxia in goats. J Appl Physiol 65: 1796–1802, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar 2008.Pawar A, Peng YJ, Jacono FJ, Prabhakar NR. Comparative analysis of neonatal and adult rat carotid body responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 104: 1287–1294, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng 2003.Peng YJ, Overholt JL, Kline D, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. Induction of sensory long-term facilitation in the carotid body by intermittent hypoxia: implications for recurrent apneas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10073–10078, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng 2004.Peng YJ, Prabhakar NR. Effect of two paradigms of chronic intermittent hypoxia on carotid body sensory activity. J Appl Physiol 96: 1236–1242; discussion 1196, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng 2006.Peng YJ, Yuan G, Ramakrishnan D, Sharma SD, Bosch-Marce M, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Heterozygous HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs carotid body-mediated systemic responses and reactive oxygen species generation in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 577: 705–716, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar 2007.Prabhakar NR, Kumar GK, Nanduri J, Semenza GL. ROS signaling in systemic and cellular responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 1397–1403, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan 2005.Ramanathan L, Gozal D, Siegel JM. Antioxidant responses to chronic hypoxia in the rat cerebellum and pons. J Neurochem 93: 47–52, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey 2004.Rey S, Del Rio R, Alcayaga J, Iturriaga R. Chronic intermittent hypoxia enhances cat chemosensory and ventilatory responses to hypoxia. J Physiol 560: 577–586, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler 1985.Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Adrenomedullary function in the neonatal rat: responses to acute hypoxia. J Physiol 358: 1–16, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler 1986.Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Non-neurogenic adrenal catecholamine release in the neonatal rat: exocytosis or diffusion? Brain Res 393: 274–277, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokowski 2005.Stokowski LA A primer on apnea of prematurity. Adv Neonatal Care 5: 155–170; quiz 171–154, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi 2001.Takeuchi Y, Mochizuki-Oda N, Yamada H, Kurokawa K, Watanabe Y. Nonneurogenic hypoxia sensitivity in rat adrenal slices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 289: 51–56, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor 1999.Taylor SC, Peers C. Chronic hypoxia enhances the secretory response of rat phaeochromocytoma cells to acute hypoxia. J Physiol 514: 483–491, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson 1997.Thompson RJ, Jackson A, Nurse CA. Developmental loss of hypoxic chemosensitivity in rat adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. J Physiol 498: 503–510, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie 2004.Xie Z, Currie KP, Fox AP. Etomidate elevates intracellular calcium levels and promotes catecholamine secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol 560: 677–690, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani 2002.Yokotani K, Okada S, Nakamura K. Characterization of functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptors involved in catecholamine release from the isolated rat adrenal gland. Eur J Pharmacol 446: 83–87, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]