Abstract

Background/Aims

Oval cells (OCs), putative hepatic stem cells, may give rise to liver cancers. We developed a carcinogenesis regimen, based upon induction of OC proliferation prior to carcinogen exposure. In our model, rats subjected to 2-acetylaminofluorene/partial-hepatectomy followed by aflatoxin injection (APA regimen) developed well-differentiated hepatocholangiocarcinomas. The aim of this study was to establish and characterize cancer cell lines from this animal model.

Methods

Cancer cells were cultured from animals sacrificed eight months after treatment, and single clones were selected. The established cell lines, named LCSCs, were characterized, and their tumorigenicity was assessed in vivo. The roles of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in LCSC growth, survival and motility were also investigated.

Results

From primary tumors, six cell lines were developed. LCSCs shared with the primary tumors the expression of various OC-associated markers, including cMet and G-CSF receptor. In vitro, HGF conferred protection from death by serum withdrawal. Stimulation with G-CSF increased LCSC growth and motility, while the blockage of its receptor inhibited LCSC proliferation and migration.

Conclusions

Six cancer cell lines were established from our model of hepatocholangiocarcinoma. HGF modulated LCSC resistance to apoptosis, while G-CSF acted on LCSCs as a proliferative and chemotactic agent.

Keywords: hepatocholangiocarcinoma, Oval cell, Liver cancer cell line, HGF, G-CSF

Introduction

Carcinogenesis is a multi-step process, involving accumulation of genetic mutations which lead to the transformation of normal cells into tumorigenic cells [1–4]. The cellular origin of tumors has been under debate for decades. It is well accepted that every proliferating cell within a tissue can be targeted by carcinogenetic stimuli and undergo the process of transformation. Tumors might then arise from mutated progenitors, which have regained the property of self-renewal, or from the transformation of resident stem cells (SCs), in which the machinery to specify and regulate self-renewal is already active [5,6].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) represent the majority of primary liver cancers [1,7]. There are occasional reports in the literature of HCC and CCC within the same liver, designated as hepatocholangiocarcinoma (HCC/CCC) [7,8]. Recently, great efforts have been made to elucidate the mechanisms underlying hepatocholangiocarcinogenesis [1,6]. Although the liver is considered a quiescent tissue, various hepatic cell types – i.e., hepatocytes, bile duct cells and their precursors, as well as bipotent liver SCs - have the ability to proliferate and might be therefore targeted by carcinogens [1,2]. Assuming that oval cells (OCs) are bipotent liver stem/progenitor cells, we developed a regimen of carcinogenesis in rats, based upon the induction of OC proliferation prior to tumor initiation. OCs were activated using the 2-acetylaminofluorene/partial-hepatectomy (2AAF/PH) regimen, which inhibits hepatocyte proliferation and forces OC recruitment [9]. Aflatoxin-B1 (AFB1) was administered during the peak of OC proliferation, resulting in tumors whose features are consistent with HCC/CCC. We named this model “APA regimen”, as the acronym for the consecutive 2AAF, PH, and AFB1 treatments [10].

The aim of the present study was to establish and characterize cell lines from HCC/CCCs induced by the above-mentioned protocol. We have established 6 cancer cell lines, termed “LCSCs”, which shared with the primary tumors the expression of OV6, CK19, AFP, OCT3/4, cMet, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and its receptor (G-CSFR). Hepatocytes growth factor (HGF) played an important role in regulating LCSC resistance to apoptosis, while G-CSF acted on LCSCs stimulating their proliferation and migration.

Materials and methods

Animals

Seventy-four F344 male rats (8–10 weeks of age) were purchased from Charles-River Laboratories. Animals were maintained on standard laboratory chow and daily cycles, alternating 12 hours of light and dark. All procedures were performed with the approval of the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee, and according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences. The experimental design is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design.

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedures administered to rats treated with the APA regimen and to control rats (2AAF/PH, 2AAF alone, 2AAF/AFB1). The timing is indicated by considering “day 0” as the day of AFB1 injection (d = day, m = months). (B) APA regimen and establishment of liver cancer cell lines. Fragments of liver cancers, obtained from rats subjected to the APA regimen and sacrificed 8 months after AFB1 injection, were disassociated and the cell suspension was seeded in culture. The established cell lines, named LCSCs, were characterized. Tumorigenicity assays were performed on rats pre-treated with MCT/PH. Cancer cell lines were established from transplanted tumors and named LCSC-Tx.

APA regimen and histopathologic analysis of liver tumors

Twenty rats were implanted intra-peritoneally (i.p.) with a time-released 2AAF pellet (2.5mg/day; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). Seven days later, animals underwent PH, as previously described [11]. At the peak of OC proliferation (day 11 post-PH), animals were injected i.p. with AFB1 (1mg/Kg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Thirty control rats were treated with either 2AAF/PH, 2AAF alone, or 2AAF/AFB1 (10 rats/subset). Rats were sacrificed at 4 and 8 months following AFB1 injection. Samples of liver tissue were collected separately in O.C.T. embedding medium, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and in paraffin following overnight fixation in 10% formalin. Routine histological examinations were made on sections stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The immunophenotyping was obtained through the analysis of various markers (Table 1). Vector ABC-kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and DAB-reagent (Dakocytomation, Carpinteria, CA) were employed in the immunoperoxidase detection procedure. For immunofluorescence staining, Vectastain kit with DAPI, Texas-red and fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) were used. Additional stains employed were Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) for mucin and Masson’s trichrome for collagen, performed by the Molecular Pathology Core at the University of Florida. Samples were photographed using an Olympus microscope and Optronics digital camera (Olympus, Melville, NY). Selected slides were also analyzed by confocal microscopy (Spectra TCS-SP2-AOBS, Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL).

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used for immunophenotype analysis. For each antibody, the molecular target, biological function, dilution (DIL) and Company name are indicated

| TARGET | FUNCTION | DIL | COMPANY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ki67 | proliferation index | 1:100 | BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA |

| OV6 | oval and ductular cell marker | 1:100 | a generous gift from Dr. Sell, Albany, NY |

| CK19 | oval and ductular cell marker | 1:100 | Dako North America, Inc. Carpinteria, CA |

| GSTp | dysplastic hepatocytes | 1:200 | MBL International, Woburn, MA |

| AFP | oval and progenitor cell marker | 1:100 | Nordic Immunological Lab., the Netherlands |

| c-Met | hepatocyte growth factor receptor; oval and progenitor cell marker | 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA |

| OCT3/4 | Transcription factor, “stemness gene” | 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA |

| G-CSF | hematopoietic stem cell mobilizing factor, also promoting proliferation of OC and migration | 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA |

| G-CSFR | hematopoietic and oval cell marker | 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA |

Establishment and characterization of LCSC lines

Tumor specimens, from rats sacrificed 8 months after AFB1 exposure, were dissociated mechanically and disaggregated by collagenase-H (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) digestion. The suspension was seeded into DMEM serum-free for 72 hours. Cells were then transferred into DMEM/F12 medium (CellGrow, Fisher) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (LCSC-medium). Subcultures were performed by trypsinization (trypsin/EDTA, CellGrow, Fisher) of confluent cells. The cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. Colonies were identified by morphology and isolated using cloning-rings (Sciencelab.com Inc., Houston, Tx). Briefly, a layer of grease was applied to the bottom edge of the ring and then inverted over each clone of choice. After adding a small volume of Trypsin/EDTA, the dish was incubated at 37°C until cells detached. Finally, clones were collected and suspended in medium for further growth. At every passage, fractions of cells were frozen in LCSC-medium supplemented with DMSO 10% in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80°C, and applied to microscope slides by cytocentrifugation (1×105 cells/slide, 41Xg, Cytospin-4, Thermo-Shandon, Cheshire, England).

LCSC Phenotype

Cells were observed daily using a phase-contrast microscope. Immunophenotype was evaluated at different passages in culture on cytospins and chamber slides (Nunc Int., Naperville, IL), by immunoperoxidase and immunofluorescence staining for the previously mentioned antibodies. Gene expression of selected transcripts was analyzed at different passages through RT-PCR (Table 2), as described elsewhere [11].

Table 2.

Primers used for the amplification of specific mRNA transcripts in LCSCs

| TARGET | SENSE STRAND | ANTISENSE STRAND |

|---|---|---|

| albumin | 5′-AAG GCA CCC CGA TTA CTC CG-3′ | 5′-TGC GAA GTC ACC CAT CAC CG-3′ |

| AFP | 5′-TCG TAT TCC AAC AGG AGG-3′ | 5′-AGG CTT TTG CTT CAC CAG-3′ |

| CK19 | 5′-AGA TCC CCA AAG ACA CGA GAT-3′ | 5′-TCA GTG GTG CTC AGT CAC AAG-3′ |

| OCT3/4 | 5′ GGC GTT CTC TTT GGA AAG GTG TTC3′ | 5′ CTC GAA CCA CAT CCT TCT CT 3′ |

| G-CSFR | 5′-CCA TTG TCC ATC TTG GGG ATC-3′ | 5′-CCT GGA AGC TGT TGT TCC ATG-3′ |

Growth kinetics

2×105 cells were seeded in six-well plates and maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cell counts were performed in triplicate on a hemocytometer by dye exclusion with trypan blue every 24 hours for 5 days.

Cytogenetic studies

Cytogenetic analysis was performed at passage 4 of the established cell lines. Cells were prepared for karyotyping by incubating with colcemid for 2 hours prior to harvest. Cells were disaggregated, exposed to hypotonic buffer, and fixed with methanol-glacial acetic acid. Air-dried chromosome spreads were banded by the Giemsa-trypsin method. Modal karyotypes were based on examination of at least 25 cells.

Tumorigenicity assays

LCSCs (5×107 cells in 0.2ml PBS) were injected into 24 syngeneic rats pretreated with monocrotaline (MCT) and PH, as described elsewhere [12]. Rats were infused intra-splenicly (3 rats/LCSC line). Two additional infusion routes were used for LCSC-2: subcutaneous and intra-hepatic (3 rats/route). The latter was performed by direct injection into the liver remnant using a 29-gauge needle attached to an insulin syringe. The development of cancer nodules was considered as a proof of LCSC tumorigenicity. High-resolution ultrasonography was employed to detect and monitor the growth of intra-abdominal masses (Vevo770 - Visualsonics, Toronto, Canada). The transplanted tumors and metastases were collected and analyzed through histology and immunohistochemistry. Cancer cells were isolated from selected nodules derived from LCSC-2, seeded, and characterized as previously described. The resulting cell lines were named LCSC-Tx and classified depending upon the organ of origin.

Assessment of the role of HGF/cMet on LCSCs

The cellular response to HGF was evaluated at both the molecular (western blot analysis) and functional (starvation regimens) levels, on LCSC-2, LCSC-5, and LCSC-Tx-skin.

Western blot analysis for Met and ERK and AKT phosphorylation following HGF stimulation

LCSCs (2.5×105 cells/well) were incubated in DMEM/F12 serum-free overnight and then cells were stimulated with HGF (50 or 100ng/ml) for 15 min. The levels of phosphorylated (Tyr 1234/1235) cMet (p-Met, Cell Signalling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), p-ERK (Biolabs, 1:1000 dilution), p-AKT (Cell Signalling Technology, 1:1000 dilution), and SHP-2 (loading control, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, 1:1000 dilution) were measured by western blot, as described elsewhere [11].

Starvation assays and protective role of HGF

Confluent cells were incubated under various selective conditions (Table 3), with or without HGF. Cells were observed daily under a phase contrast microscope for up to 7 days, to monitor any change in number and morphology/viability.

Table 3.

Nutrient-depleted media used for starvation assays

| NUTRIENT-DEPLETED MEDIA |

|---|

| DMEM, 4.5 g/L Glucose, 5% FBS (control) |

| DMEM, 4.5 g/L Glucose, no FBS |

| DMEM, no Glucose, 5% FBS |

| DMEM, no Glucose, no FBS |

| DMEM, 4.5g/L Glucose, no FBS, 10ng/ml HGF |

Assessment of the role of G-CSF/G-CSFR on LCSCs

To stimulate LCSCs, we employed recombinant methionyl-human G-CSF (Filgrastim, Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) at the dose of 100ng/ml. To inhibit G-CSFR, we employed an antibody raised against the C-terminus of G-CSFR of mouse origin, cross-reacting with rat G-CSFR, at a dosage of 2μg/ml. In order to validate the results, both the proliferation and the migration assay were performed on cultured OCs (HOC-3 line). Briefly, HOC-3 was established from isolated OCs, obtained as described elsewhere [13], and maintained in culture in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium with 10% FBS and antibiotics. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Proliferation assay

1×105 cells, seeded in six-well plates, were cultured under the following conditions: DMEM/F12 with 0.5% BSA (negative control), DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS (positive control), DMEM/F12 with 0.5% BSA supplemented with G-CSF, and DMEM/F12 with 0.5% BSA supplemented with anti-G-CSFR antibody. Cell counts were performed on trypsinized cells every subsequent 24 hours for 3 days.

Migration assay

Transwell culture dishes with 5μm pore filters (Coring Inc. Costar, NY) were pre-coated overnight with rat-tail collagen. Cells (5×104) were suspended in LCSC-medium, and allowed to attach overnight. After removal of non-adherent cells, transwells were either transferred in migration buffer (DMEM/F12), or incubated with anti-G-CSFR (in migration buffer) for 1 hour at 37° C, 5% CO2. Transwells were then washed, and incubated with G-CSF (100ng/ml in migration buffer), at 37° C, 5% CO2, for 5 hours. As controls, G-CSF was either excluded from the lower chamber (migration control) or added to both chambers (chemokinetic control). At the end of the assay, cells that had migrated to the bottom of the transwell filter were fixed, stained, and counted. Data were normalized for each independent experiment with respect to the migration control, and expressed as relative chemotactic index.

Statistical analysis

Values presented are expressed as mean±SD. After acquiring all data, Student’s t-test (one tail) was applied to determine statistical significance. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed by Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

Combined hepatocholangiocarcinoma following the APA regimen

In all the animals subjected to the APA regimen, the liver remnant presented a cirrhotic degeneration, with grossly apparent nodules, the borders of which were defined by fibrotic cords (Fig 2A), mainly populated by OV6+ cells (Fig 2B), denoting a persistent OC reaction. There was evidence of both cholangiolar and hepatocellular differentiation within these cords (Fig 2C) and all of the cancers described were found to be connected to, and likely arose from them. These features were present in rats sacrificed 4 months after AFB1 and were maintained at 8 months. All the animals treated with the APA regimen developed liver cancers, with an average of five tumors per animal. Histologically, tumors were well differentiated HCC/CCC. HCC foci displayed solid trabecular and pseudo-glandular areas of dysplastic cells with moderate to high polymorphism (Fig 2D), expressing Ki67 (Fig 2E) and GSTp (Fig 2F). HCC areas were adjacent to large foci of dysplastic GSTp+/OV6+/CK19+ highly proliferating cells (Fig 2G–J), with intestinal metaplasia (Fig 2K) and cholangiofibrosis (Fig 2L), both hallmarks of CCC. AFP was expressed in both HCC and CCC areas (staining not shown). G-CSF and its receptor were co-expressed in CCC and HCC areas (Fig 3A–C). Many cancer cells also expressed G-CSFR (Fig. 3D–F). Moreover, a large proportion of tumor cells were cMet+ (Fig 3G,H). Conversely, OCT3/4 was rarely seen in tumors and it was expressed by very minute OV6+ cells, as clusters or single elements (Fig 3I–L). Table 4 summarizes the immunohistochemical profile of the HCC/CCC specimens. None of the control groups presented with dysplastic features, persistent OC activation, or cancers, at 4 and 8 months.

Figure 2. The APA regimen induced well-differentiated hepatocholangiocarcinomas.

The liver remnant presented a cirrhotic degeneration, with grossly apparent nodules, the borders of which were defined by fibrotic cords (A, arrows), mainly comprised by OV6 + cells (B; the insert depicts an OV6+ cord at higher magnification). There was evidence of both hepatocellular and cholangiolar differentiation within these cords (C, arrows and arrow-head, respectively). Nodules of well-differentiated HCC displayed a frequent pseudoglandular pattern (D) and were populated by dysplastic Ki67+ (E) and GSTp+ (F) cells. The CCC areas (G) were formed by large foci of dysplastic Ki67+ (H), OV6+ (I), CK19+ (J) cells. Mucin accumulation within the aberrant ducts, indicating intestinal metaplasia (K), and a moderate degree of cholangiofibrosis (L) were also noted. Panels A, B, G, H, I, J, K, and L depict liver sections obtained from rats sacrificed 8 months after AFB1 injection; the remaining panels (C–F) represent sections from rats sacrificed 4 months after AFB1 injection.

Figure 3. hepatocholangiocarcinomas expressed G-CSF, G-CSFR, OV6, cMet and OCT3/4.

G-CSF and its receptor were co-expressed in HCC and CCC areas. Panels (A–C) illustrate G-CSFR (green, A)/G-CSF (red, B) double-positive cancer cells (yellow, C) within an area of HCC. Panels (D–F) show a CCC area where many OV6+ cancer cells (red, E) co-expressed G-CSFR (green, D); panel F depicts the merging panel (yellow). Representative double-positive cells and clusters are indicated by arrows and arrow-heads, respectively. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). A large proportion of cancer cells were cMet+ (G, H - the latter depicts cMet+ cells at higher magnification). Conversely, very few cancer cells, small in size, expressed OCT3/4 (panel I shows OCT3/4+ cells within an HCC area). Panels (J–L) indicate one OCT3/4+ cancer cell (green, J) co-expressing OV6 (red, K) in a CCC focus. Merging panel is depicted in L (yellow). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). OCT3/4+ cells in panels (I–L) are indicated by arrows.

Table 4.

Immunohistochemical profile of HCC/CCC from rats subjected to the APA protocol. Percentage of cells that are positive for each marker as obtained through the analysis of 5–8 fields selected randomly from each specimen (20x objective magnification). Values presented are expressed as mean±SD (with the exception of OCT3/4, given the extreme rarity of positive cells)

| ANTIGEN | TUMOR DISTRIBUTION | PERCENTAGE OF POSITIVE CELLS |

|---|---|---|

| GSTp | Dysplastic hepatocytes and ductular cells | 94±4 HCC |

| 79±12 CCC | ||

| OV6 | Dysplastic and normal ductular cells, oval cells | 15±4 HCC |

| 96±3 CCC | ||

| CK19 | Dysplastic and normal ductular cells | 9±3 HCC |

| 98±2 CCC | ||

| AFP | Dysplastic hepatocytes and ductular cells, oval cells | 47±14 HCC |

| 16±9 CCC | ||

| G-CSF | Dysplastic hepatocytes, periductular and ductular tumor cells, oval cells | 35±8 HCC |

| 31±11 CCC | ||

| G-CSFR | Dysplastic hepatocytes, periductular and ductular tumor cells, oval cells | 22±6 HCC |

| 41±16 CCC | ||

| cMet | Dysplastic hepatocytes and ductular cells | 33±7 HCC |

| 28±13 CCC | ||

| OCT3/4 | Very small undifferentiated tumor cells, in small clusters | <1 HCC |

| <1 CCC |

Establishment and characterization of LCSC lines

From primary cultures, 18 colonies were isolated and 6 LCSC lines were established. LCSCs were maintained through multiple passages (>60) without senescence, proved to be stable and consisted of a main fraction of relatively small cells, named Ep-LCSCs, which displayed an epithelioid, polygonal-shaped morphology, clear cytoplasm, and large nuclei, containing several prominent nucleoli (Fig 4A,C). A second, minor fraction, represented cells of very minute size (<10μm) and scant cytoplasm, named Sm-LCSCs. These cells were usually observed as isolated elements, small clusters, and rarely forming cords or spheroid aggregates (Fig 4A–C). Following ring-isolation, Sm-LCSCs were able to give rise to progenies of epithelioid cells that were morphologically indistinguishable from Ep-LCSCs. Many Ep-LCSCs and Sm-LCSCs stained positive for AFP (Fig 4D–F), G-CSF and its receptor (Fig 4G–I), OV6 (Fig 4J–K), and cMet (Fig 5A). LCSCs also expressed other liver-associated transcripts, such as albumin and CK19 (Fig. 6A). This expression profile was retained at late passages in culture (Fig 6B). OCT3/4 RNA was present in all LCSC lines (Fig 6A). Interestingly, only Sm-LCSCs stained positive for this transcription factor (Fig 5H–L). As for the growth kinetics, LCSCs rapidly entered logarithmic growth phase, with an average doubling time of 18 hours, loss of contact inhibition and ability to grow in multiple layers after reaching confluence (fig 6C). Cytogenetic analysis demonstrated aneuploid chromosome counts, with >60% of the analyzed metaphase spreads having chromosome counts ranging from 40 to 44. The modal chromosome number was 41 (Fig 6D).

Figure 4. LCSC morphology and expression pattern for AFP, OV6, G-CSF, and its receptor (A–C).

All LCSC lines consisted of a main fraction of relatively small cells, which displayed an epithelioid, polygonal-shaped morphology, clear cytoplasm, and large, round or oval nuclei, containing several prominent nucleoli (A,C). A second small fraction, within LCSCs, represented cells of very minute size and scant cytoplasm, named Sm-LCSCs, which were usually observed as isolated cells/small clusters (A-C, arrows) and also spheroid aggregates (B, area). Many Ep-LCSCs and Sm-LCSCs stained positive for AFP, as showed in panels D–F (single immunofluorescence; arrows point at single Sm-cells). G-CSFR was expressed by a large percentage of LCSCs (G,J, green), co-localizing with G-CSF (H, red), and OV6 (K, red). Merging panels are depicted respectively in I and L, respectively (in J–L, double positive cells are indicated by arrows).

Figure 5. LCSC expression pattern for cMet, OV6, and OCT3/4.

Many cells within all lines also expressed cMet (A). Panels B and C depict clusters of OCT3/4+ Sm-LCSC cells (areas). OCT3/4 (D,G, green) was found in co-expression with OV6 (E,H, red), by very rare, small cells corresponding to Sm-LCSCs. Merging panels are depicted in F and I, respectively (double positive cells are indicated by arrows). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

Figure 6. LCSC gene expression profile, growth kinetics and karyotype.

Panel A depicts LCSC-2 and LCSC-4 gene expression for alphafetoprotein (AFP), albumin (Alb), G-CSFR, CK19 and OCT3/4. LCSCs expressed the above mentioned genes at early passages and retained this phenotype at late passages: panel B depicts a representative RT-PCR (from LCSC-2) for Alb and AFP at passage 4 (P4) and 30 (P30), versus negative and positive controls (ctrl- and ctrl+, respectively). A representative growth kinetics (from LCSC-2) is shown in panel C. The diagram in panel D shows the ploidy analysis of LCSCs, in terms of distribution of chromosome numbers per cell; representative images of karyotypes from normal rat cells and cancer cells are also displayed.

LCSC tumorigenicity and metastatic potential

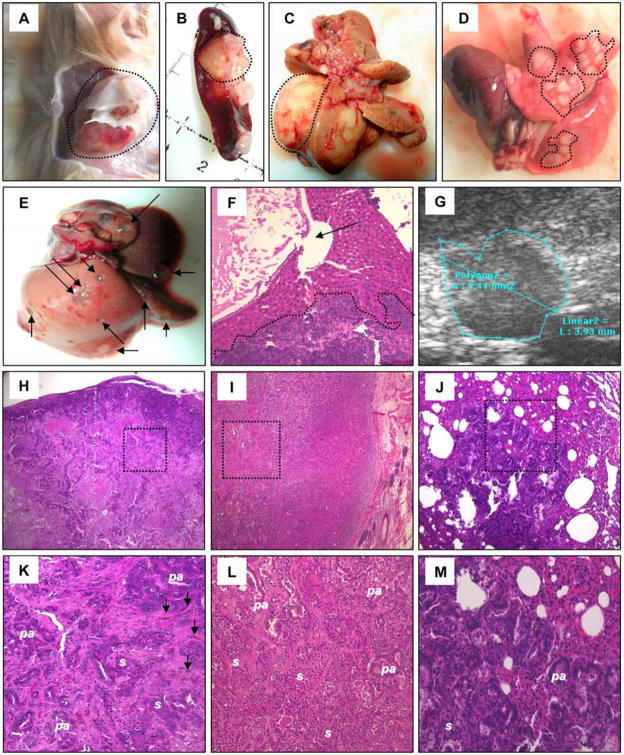

LCSCs were injected into F344 rats following MCT/PH and the animals were monitored for cancer development. All animals survived this procedure, developed tumors and were euthanized upon showing signs of disease. LCSC-2 and LCSC-4 gave rise to the most aggressive phenotypes that often metastasized to the lung and liver. Rats injected subcutaneously developed a visible tumor at the site of inoculation after approximately 8–10 weeks. Four months after LCSCs administration, large nodules (up to 2.5cm in diameter) were documented. Metastases were found within lungs and liver, the latter associated with cystic dilations of the biliary tree, from mechanical compression due to tumor growth (Fig 7A–F). Intra-abdominal cancers were detectable by ultrasonography in asymptomatic animals after about 1 month following LCSCs injection (Fig 7G). Histologically, the tumors were mixed CCC/HCC, consisting of epithelioid LCSC-like cells, with solid or pseudo-acinar organization, and occasional mucin and bile deposition (Fig 7H–M). The immunophenotype of the transplanted tumors was similar to that of primary cancers, although cancer cells tended to be less differentiated. Table 5 summarizes the immunohistochemical profile of the transplanted tumors. Cancer cells were isolated from three LCSC-2-derived nodules (1 sub-cutaneous, 1 intra-splenic cancer, and 1 pulmonary metastasis). From primary cultures, three LCSC-Tx lines (1 line/tumor) were established (named LCSC-Tx-skin, -spleen, and -lung, respectively). In culture, all LCSC-Tx cells proved to be similar to the original LCSC phenotype, in terms of morphology (each line comprising of Ep and Sm separate fractions), and immunophenotype (Fig 8).

Figure 7. Tumorigenicity assays.

Representative pictures of transplanted tumors (at about 4 months following LCSC-2 transplantation), within skin (A), spleen (B) and liver (C), are shown (areas). Panels (D–F) illustrate the aspect of multiple pulmonary metastases (D, areas) and cystic dilations of the biliary tree (E,F; arrows) associated with hepatic metastases (F, area), at about 4 months following LCSC-2 transplantation. Panel G depicts an intra-hepatic small nodule detected by ultrasonography in an asymptomatic animal after about 1 month following injection of LCSC-4. (H–M) Histologically, the tumors were mixed CCC/HCC, consisting of epithelioid LCSC-like cells, with solid (s) or pseudo-acinar (pa) organization. The following representative images of cancer nodules are depicted (at low and high magnification, respectively): intra-splenic tumor (H, K), sub-cutaneous tumor (I, L), and lung metastasis (J, M). Bile accumulations are pointed out by arrows in panel K.

Table 5.

Immunohistochemical profile of transplanted tumors from rats subjected to LCSC injection. Percentage of cells that are positive for each marker as obtained through the analysis of 5–8 fields selected randomly from each specimen (20x objective magnification). Values presented are expressed as mean±SD (with the exception of OCT3/4, given the extreme rarity of positive cells)

| ANTIGEN | PERCENTAGE OF POSITIVE CELLS |

|---|---|

| GSTp | 63±10 |

| OV6 | 45±14 |

| CK19 | 58±6 |

| AFP | 39±12 |

| G-CSF | 19±8 |

| G-CSFR | 38±7 |

| cMet | 26±5 |

| OCT3/4 | <1 |

Figure 8. LCSC-Tx characterization.

(A–C)Section of an intra-splenic tumor (obtained following LCSC-2 injection) showing G-CSFR expression (A, green) in co-localization with OV6 (B, red) in cancer cells. Panel C results from the merging of A and B. Representative double-positive cells and clusters are indicated by arrows and arrow-heads, respectively. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (D) Representative image of LCSC-Tx morphology, showing a cluster of Sm-cells (area) surrounded by Ep-cells (from LCSC-Tx-spleen). (E) RT-PCR for G-CSFR gene expression in LCSC-Tx-spleen, -lung, and –skin (= S.C.): all cell lines expressed G-CSFR mRNA. (F–L) LCSC-Tx-spleen expressed OV6 (F, K,L) and co-expressed G-CSFR/G-CSF (G-I), and G-CSFR/OV6 (J–L). Representative double-positive cells are indicated by arrows. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

Role of HGF/cMet on LCSCs

cMet, the HGF receptor, is frequently over-expressed in invasive and metastatic malignancies [14]. LCSCs and LCSC-Tx responded to HGF, by increasing the phosphorylation of cMet and its downstream effectors (p-ERK, p-AKT) (Fig 9A–B). Under starvation conditions (reduced/absent glucose and/or FBS), the Ep-LCSC fraction rapidly detached from the plate and died, while the Sm-LCSC fraction survived, cords of small round cells being still preserved up to day 7. The addition of HGF was able to protect Ep-LCSCs from death, conferring the ability to survive in FBS-depleted medium (fig 9C–F).

Figure 9. Role of HGF/cMet on LCSC survival.

Panel A depicts the response of LCSC-5 to HGF stimulation (western blot): LCSCs were able to respond to HGF (50 or 100 ng/ml), by increasing the phosphorylation of cMet (p-Met) and of its downstream transducer ERK1/2 kinase (p-ERK). SHP-2 served as loading control. Panel B shows the response of LCSC-2 and of LCSC-Tx-skin to HGF stimulation (100 ng/ml): both lines responded to HGF by increasing the phosphorylation of Met and of its downstream effectors (ERK, AKT). Panels C–F: LCSC-2 incubated in starvation conditions (at day 5) with or without HGF: DMEM, 4.5 g/L Glucose, no FBS (C), DMEM, no Glucose, 5% FBS (D), DMEM, no Glucose, no FBS (E), DMEM, 4.5g/L Glucose, no FBS, 10ng/ml HGF (F). Arrows indicates Sm-LCSC cords; the letter “a” marks zones of Ep-LCSCs loss; areas in panel F include surviving Ep-LCSCs.

Role of G-CSF/G-CSFR on LCSCs

The effects of anti-G-CSFR were tested on a line of liver OCs (HOC-3) and on LCSCs. We confirmed that G-CSF is able to increase OC proliferation and exert a significant chemotactic effect, contributing to OC migration [11]. Conversely, incubation with anti-G-CSFR antibody resulted in an almost complete inhibition of the OC proliferative potential and also prevented OC from migrating in response to a G-CSF gradient. Similarly, LCSC proliferation was stimulated by G-CSF, while incubation with anti-G-CSFR significantly reduced the capacity of LCSC to proliferate (Fig 10A). Moreover, LCSCs were able to migrate following a G-CSF gradient, whereas pretreatment with anti-G-CSFR antibody was able to prevent cell migration (Fig 10B).

Figure 10. Role of G-CSF on LCSC Proliferation and migration.

Diagrams depicting the effects of both G-CSF and anti-G-CSFR on cultured liver oval cells (HOC) and on LCSCs (line 2). The exact p values are reported. Panel A: G-CSF, at the dose of 100 ng/ml, was able to increase HOC proliferation when compared to the controls. Conversely, incubation with anti-G-CSFR resulted in an almost complete inhibition of the HOC proliferative potential (upper diagram). Similarly, LCSC proliferation was stimulated by G-CSF, while incubation with anti-G-CSFR significantly reduced the capacity of LCSC to proliferate (lower diagram). Abbreviations: negative control (ctrl-), positive control (ctrl+), experimental group treated with G-CSF (G-CSF), experimental group treated with anti-G-CSFR antibody (anti-G-CSFR). Panel B: G-CSF, at the dose of 100 ng/ml, was able to exert a significant chemotactic effect, contributing to HOC migration. Conversely, incubation with anti-G-CSFR prevented HOC from migrating in response to a G-CSF gradient (white bars). Similarly, LCSC were able to migrate following a G-CSF gradient, whereas pre-treatment with anti-G-CSFR prevented cell migration (black bars). Abbreviations: migration control (N/N), chemokinetic control (G-CSF added to both chambers, GF/GF), experimental group (G-CSF added to the lower chamber, N/GF), experimental group of cells pre-treated with anti-G-CSF antibody and then G-CSF added to the lower chamber (PRE-N/GF), migration control for pre-treated cells (PRE-N/N).

Discussion

Although the liver is classically considered a quiescent organ, several hepatic cell types with proliferation potential have been identified [1,15,16]. Whenever the replication ability of hepatocytes is impaired, liver regeneration can be accomplished by the activation of putative liver SCs, named “oval cells” in rodents, which can differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes [1,15,16]. All the hepatic cell types with proliferation potential may give rise to liver tumors, including OCs [1,17,18]. In the APA model, the 2AAF/PH regimen specifically inhibited hepatocyte proliferation and forced the activation of OCs, which became the main target of carcinogen exposure. Since liver OCs are bipotential, their initiation might explain the coexistence of both CCC and HCC phenotype. Typically, AFB1 administration in rats results in HCCs arising from hepatocytes, although it might also give rise to CCC [19]. Cyclic feeding with high doses of 2AAF has been shown to induce neoplastic nodules in rats [20]. However, in our model, control rats did not develop liver cancers. The critical combination for HCC/CCC development in the APA model appears to be activation of the OC compartment followed by AFB1 exposure. The fact that hepatocyte proliferation was inhibited at the time of carcinogen exposure, the tumor histotype, and the association of neoplasias with cords of oval cells, support a bipotential stem/progenitor cell origin of the cancers [manuscript submitted for publication].

We established six cell lines from our model of HCC/CCC. LCSCs shared with the primary tumors the expression of biliary markers (OV6, CK19), hepatocyte markers (albumin), OC markers (OV6, AFP, cMet and G-CSFR), and putative tumor-initiating cell markers (OCT3/4). To assess the tumorigenic potential of LCSCs, cells were injected into secondary recipients. It is worth noting that, we infused a relatively large number of cells (5×107) to recipient animals, as compared to other studies [3,21,22]. In these experiments, we transplanted unsorted LCSCs, which most likely contain a small percentage of tumorigenic cells along with a preponderance of more differentiated cells. Several studies have attempted to isolate the tumor-initiating cell fraction from liver cancer cell lines [21–24]. In our study, suitable candidates might be the Sm-LCSCs, that express OCT3/4, a transcription factor involved in self-renewal and pluripotency of undifferentiated embryonic SCs [25,26]. OCT3/4 has been observed in various human cancers, including HCCs [26–29]. OCT3/4 expression in tumorigenic cells may contribute to maintenance of both pluripotency and self-renewal [30]. In our model, small OCT3/4+ cells were observed within HCC/CCC nodules. Their counterpart in culture are likely the Sm-LCSCs, which showed unique biological properties (resistance to apoptosis, capacity to generate the epithelioid fraction overtime). Further in vivo and in vitro assays on isolated Sm-LCSCs are required to support this hypothesis and are currently underway in our laboratory.

Most of the HCC/CCC cells were cMet+ and G-CSFR+ and LCSCs retained this phenotype in culture. HGF is the most potent growth factor for hepatocytes and binds to its only known high-affinity receptor, cMet. The HGF/cMet signalling system is essential for liver development, homeostasis, and function and it plays a pivotal role in OC survival and proliferation [31,32]. Over-expression of cMet has been found in many invasive and metastatic cancers, including CCC and HCC [33]. Indeed, cMet stimulation activates multiple signal pathways such as ERK1/2 and PI3k, which seem to play a key-role in tumor invasion and metastasis [14]. In our model, cMet was strongly expressed by LCSCs, which were able to respond to HGF stimulation, and HGF protected LCSCs from apoptosis.

G-CSF is involved in the proliferation and differentiation of granulocytes and their precursors, as well as in hematopoietic SC mobilization [34,35]. G-CSFR is expressed by OCs and exerts beneficial effects on hepatic regeneration [11]. However, G-CSFR is also expressed by various carcinoma lines and solid tumors, including liver malignancies [36-38]. Although the mechanism by which certain cancers produce G-CSF remains unclear, it has been reported that an intimate relationship exists between the production of G-CSF in cancer cells and their de-differentiation [38]. Our results suggest that the G-CSF/G-CSFR axis might be involved in HCC/CCC development and progression. Since G-CSF is currently administered together with high-dose chemotherapies for the treatment of various cancers, our results, should they be confirmed in human liver malignancies, provide a strong incentive to screen for the tumor expression of G-CSFR prior to G-CSF administration.

Further efforts are required to clarify the mechanisms underlying the G-CSF/G-CSFR and HGF/cMet pathways in liver cancers and to develop targeted treatments in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PF-05-165-01 (T.D. Shupe) from the American Cancer Society, by 2R01DK058614-05 and R01DK065096 (B.E. Petersen) from NIH, and by an unrestricted grant from “Fondazione Ricerca in Medicina”, Italy (A.C.P.)

ABBREVIATIONS

- SCs

Stem cells

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CCC

Cholangiocarcinoma

- HCC/CCC

Hepatocholangiocarcinoma

- OCs

Oval cells

- 2AAF

2-Acetylaminofluorene

- PH

Partial hepatectomy

- AFB1

aflatoxin-B1

- APA regimen

2AAF, PH, and AFB1 treatments

- LCSCs

Liver Cancer Stem-cell-derived Cell lines

- G-CSF

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- HGF

Hepatocytes growth factor

- G-CSFR

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptor

- i.p

intra-peritoneally

- PAS

Periodic acid Schiff

- MCT

Monocrotaline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Piscaglia AC, Shupe DT, Petersen BE, Gasbarrini A. Stem Cells, Cancer, Liver, and Liver Cancer Stem Cells: Finding a Way out of the Labyrinth…. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:582–590. doi: 10.2174/156800907781662293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Neaves WB. Normal stem cells and cancer stem cells: the niche matters. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4553–4557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piscaglia AC. Stem cells, a two-edged sword: Risks and potentials of regenerative medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4273–4279. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piscaglia AC, Shupe DT, Gasbarrini A, Petersen BE. Microarray RNA/DNA in Different Stem Cell Lines. Curr Pharm Biotechnol J. 2007;8:167–175. doi: 10.2174/138920107780906478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojiro M. Histopathology of liver cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:39–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang F, Chen XP, Zhang W, Dong HH, Xiang S, Zhang WG, et al. Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma originating from hepatic progenitor cells: immunohistochemical and double-fluorescence immunostaining evidence. Histopathology. 2008;52:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen BE, Zajac VF, Michalopoulos GK. Hepatic oval cell activation in response to injury following chemically induced periportal or pericentral damage in rats. Hepatology. 1998;27:1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shupe TD, Piscaglia AC, Petersen BE. Induction of oval cell proliferation prior to AFB1 exposure results in the development of both HCC and CCC in rats. Cancer Res. 2006;47:5201. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piscaglia AC, Shupe TD, Oh S, Gasbarrini A, Petersen BE. Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor Promotes Liver Repair and Induces Oval Cell Migration and Proliferation in Rats. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:619–631. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh SE, Witek RP, Bae SH, Zheng D, Jung Y, Piscaglia AC, et al. Bone-Marrow Derived Hepatic Oval Cells Differentiate into Hepatocytes in 2-Acetylaminofluorene/Partial Hepatectomy-Induced Liver Regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1077–1087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shupe TD, Piscaglia AC, Oh SH, Gasbarrini A, Petersen BE. Isolation and characterization of hepatic stem cells, or “oval cells,” from rat livers. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;482:387–405. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leelawat K, Leelawat S, Tepaksorn P, Rattanasinganchan P, Leungchaweng A, Tohtong R, et al. Involvement of c-Met/Hepatocyte Growth Factor Pathway in Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Invasion and Its Therapeutic Inhibition with Small Interfering RNA Specific for c-Met. J Surg Res. 2006;136:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piscaglia AC, Novi M, Campanale M, Gasbarrini A. Stem Cell-Based Therapy in Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008;17:100–118. doi: 10.1080/13645700801969980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piscaglia AC, Di Campli C, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Stem cells: new tools in gastroenterology and hepatology. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alison MR, Lovell MJ. Liver cancer: the role of stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2005;38:407–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumble ML, Croager EJ, Yeoh GC, Quail EA. Generation and characterization of p53 null transformed hepatic progenitorcells: oval cells give rise to hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:435–445. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore MR, Pitot HC, Miller EC, Miller JA. Cholangiocellular carcinomas induced in Syrian golden hamsters administered aflatoxin B1 in large doses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;68:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gil-Benso R, Martinez-Lorente A, Pellin-Perez A, Navarro-Fos S, Gregori-Romero MA, Carda C, et al. Characterization of a new rat cell line established from 2′AAF-induced combined hepatocellular cholangiocellular carcinoma in Vitro. Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2001;37:17–25. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2001)037<0017:COANRC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suetsugu A, Nagaki M, Aoki H, Motohashi T, Kunisada T, Moriwaki H. Characterization of CD133+ hepatocellular carcinoma cells as cancer stem/progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:820–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin S, Li J, Hu C, Chen X, Yao M, Yan M, et al. CD133 positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells possess high capacity for tumorigenicity. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1444–1450. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Iwama A, et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44:240–251. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rountree CB, Senadheera S, Mato JM, Crooks GM, Lu SC. Expansion of liver cancer stem cells during aging in methionine adenosyltransferase 1A-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2008;47:1288–1297. doi: 10.1002/hep.22141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers I. The molecular basis of pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cloning Stem Cells. 2004;6:386–391. doi: 10.1089/clo.2004.6.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidekel S, Pizov G, Bergman Y, Pikarsky E. Oct-3/4 is a dose-dependent oncogenic fate determinant. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:361–370. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs CP, Kukekov VG, Reith JD, Tchigrinova O, Suslov ON, Scott EW, et al. Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: implications for tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 2005;7:967–976. doi: 10.1593/neo.05394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atlasi Y, Mowla SJ, Ziaee SA, Bahrami AR. OCT-4, an embryonic stem cell marker, is highly expressed in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1598–1602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Y, Kitisin K, Jogunoori W, Li C, Deng CX, Mueller SC, et al. Progenitor/stem cells give rise to liver cancer due to aberrant TGF-beta and IL-6 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2445–2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trosko JE. From adult stem cells to cancer stem cells: Oct-4 Gene, cell-cell communication, and hormones during tumor promotion. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1089:36–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Castillo G, Factor VM, Fernández M, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Fabregat I, Thorgeirsson SS, et al. Deletion of the Met Tyrosine Kinase in Liver Progenitor Oval Cells Increases Sensitivity to Apoptosis in Vitro. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1238–1247. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okano J, Shiota G, Matsumoto K, Yasui S, Kurimasa A, Hisatome I, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor exerts a proliferative effect on oval cells through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breuhahn K, Longerich T, Schirmacher P. Dysregulation of growth factor signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:3787–3800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziegler SF, Bird TA, Morella KK, Mosley B, Gearing DP, Baumann H. Distinct regions of the human granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor receptor cytoplasmic domain are required for proliferation and gene induction. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2384–2390. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter MG, Jacob A, O’donnell LC, Agler A, Druhan LJ, Coggeshall KM, et al. Loss of SHIP and CIS recruitment to the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor contribute to hyperproliferative responses in severe congenital neutropenia/acute myelogenous leukemia. J Immunol. 2004;173:5036–5045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukunaga R, Seto Y, Mizushima S, Nagata S. Three different mRNAs encoding human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8702–8706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang SY, Chen LY, Tsai TF, Su TS, Choo KB, Ho CK. Constitutive production of colony-stimulating factors by human hepatoma cell lines: possible correlation with cell differentiation. Exp Hematol. 1996;24:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araki K, Kishihara F, Takahashi K, Matsumata T, Shimura T, Suehiro T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma producing a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: report of a resected case with a literature review. Liver Int. 2007;27:716–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]