Abstract

The structure-activity relationship of 18-carbon fatty acids (C18 FAs) on human neutrophil functions and their underlying mechanism were investigated. C18 unsaturated (U)FAs potently inhibited superoxide anion production, elastase release, and Ca2+ mobilization at concentrations of <10 μM in formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (FMLP)-activated human neutrophils. However, neither saturated FA nor esterified UFAs inhibited these neutrophil functions. The inhibitory potencies of C18 UFAs decreased in the following order: C18:1 > C18:2 > C18:3 > C18:4. Notably, the potency of attenuating Ca2+ mobilization was closely correlated with decreasing cellular responses. The inhibitions of Ca2+ mobilization by C18 UFAs were not altered in a Ca2+-containing Na+-deprived medium. Significantly, C18 UFAs increased the activities of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) in neutrophils and isolated cell membranes. In contrast, C18 UFAs failed to alter either the cAMP level or phosphodiesterase activity. Moreover, C18 UFAs did not reduce extracellular Ba2+ entry in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated neutrophils. In summary, the inhibition of neutrophil functions by C18 UFAs is attributed to the blockade of Ca2+ mobilization through modulation of PMCA. We also suggest that both the free carboxy group and the number of double bonds of the C18 UFA structure are critical to providing the potent anti-inflammatory properties in human neutrophils.

Keywords: calcium, cAMP, structure-activity relationship, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase

FAs have been reported to exert their effects by modulating immune cell functions, resulting in stimulation and/or inhibition of the production of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid mediators, and antibodies (1–3). PUFAs are thought to play an important function in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases (4–7). Alterations in dietary levels of linear-chain 18-carbon (C18) unsaturated (U)FAs have significant benefits in cardiovascular diseases and inflammatory syndromes (8–12). However, not all studies support the anti-inflammatory role of C18 FAs in neutrophils. Depending on the experimental conditions, C18 FAs can either inhibit or enhance neutrophil activation. For example, the saturated FA, stearic acid (SA; C18:0), and the UFAs, oleic acid (OA; C18:1n-9), linoleic acid (LA; C18:2n-6), and γ-linolenic acid (γLA; C18:3n-6), have been shown to elicit ROS generation, CD11b expression, leukotriene B4 production, and/or β-glucuronidase release (13–17). In contrast, some studies reported that OA, LA, and γLA inhibit ROS generation, myeloperoxidase release, and/or phagocytosis in neutrophils (18, 19). The controversial results of those studies may be due to different concentrations used. For example, OA and LA at high concentrations (100 and 1,000 μM) induced ROS production by themselves, whereas both C18 UFAs at low concentrations (1–10 μM) inhibited formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (FMLP)-activated ROS release in human neutrophils (20). OA at high (40 and 80 μM) but not low concentrations (2.5, 5, and 10 μM) elicited CD11b expression in human neutrophils (15). Obviously, further research is needed to clarify the effects and action mechanisms of C18 FAs in neutrophil functions.

Neutrophils play a pivotal role in the defense of the human body against infections. However, overwhelming activation of neutrophils is known to elicit tissue damage. Human neutrophils are known to play important roles in the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, sepsis, and atherogenesis (21–24). In response to diverse stimuli, activated neutrophils secrete a series of cytotoxins, such as the superoxide anion (O2•−), a precursor of other ROS, granule proteases, and bioactive lipids (25, 26). O2•− production is linked to the killing of invading microorganisms, but it can also directly or indirectly cause damage by destroying surrounding tissues. Neutrophil granules contain many antimicrobial and potentially cytotoxic substances. Neutrophil elastase is a major secreted product of stimulated neutrophils and a major contributor to the destruction of tissue in chronic inflammatory disease (27). Therefore, it is crucial to restrain respiratory burst and degranulation in physiological conditions while potentiating these functions in infected tissues and organs.

In this study, the effects of a series of linear-chain C18 FAs on respiratory burst and degranulation were studied in human neutrophils. We found that C18 UFAs significantly inhibited the generation of O2•− and release of elastase at concentrations of <10 μM in FMLP-activated human neutrophils. However, C18 saturated FA and esterified UFAs caused no inhibition. Furthermore, our results reveal a close correlation of the inhibition of O2•− and elastase release with attenuation of the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). FMLP, via a G-protein-coupled receptor, mobilizes rapid Ca2+ release from inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3)-sensitive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores. Such Ca2+ release depletes ER Ca2+ stores and subsequently activates extracellular Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane (28). The magnitude and duration of [Ca2+]i signal responses to G-protein-coupled chemoattractants are obviously important. Herein, we also discuss possible mechanisms of C18 UFAs that can account for their modulation of [Ca2+]i in human neutrophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

C18 FAs (obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in absolute ethanol and stored under a nitrogen atmosphere at −20°C before use. The final concentration of ethanol in the cell experiments did not exceed 0.1% and did not affect the parameters measured. HBSS was purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY). A23187, aprotinin, H89 (N-(2-((p-bromocinnamyl)amino)ethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide), leupeptin, PMSF, and Ro318220 (3-(1-(3-(amidinothio)propyl-1H-indol-3-yl))-3-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)maleimide) were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Fluo 3-AM and fura 2-AM were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Preparation of human neutrophils

Blood was taken from healthy human donors (20–32 years old) by venipuncture, using a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Neutrophils were isolated with a standard method of dextran sedimentation prior to centrifugation in a Ficoll Hypaque gradient and the hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes. Purified neutrophils that contained >98% viable cells, as determined by the trypan blue exclusion method, were resuspended in Ca2+-free HBSS buffer at pH 7.4 and maintained at 4°C before use.

Measurement of O2•− generation

The O2•− generation assay was based on the superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c. In brief, after supplementation with 0.5 mg/ml ferricytochrome c and 1 mM Ca2+, neutrophils (6 × 105/ml) were equilibrated at 37°C for 2 min and incubated with FAs for 5 min. Cells were activated with 100 nM FMLP, 0.5 μM thapsigargin, or 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 10 min. When FMLP and thapsigargin was used as a stimulant, 1 μg/ml cytochalasin B (CB) was incubated for 3 min before activation. Changes in absorbance with the reduction of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm were continually monitored in a double-beam, six-cell positioner spectrophotometer with constant stirring (Hitachi U-3010; Tokyo, Japan). Calculations were based on differences in the reactions with and without SOD (100 U/ml) divided by the extinction coefficient for the reduction of ferricytochrome c (ɛ = 21.1/mM/10 mm).

The O2•−-scavenging ability of FAs was determined using xanthine/xanthine oxidase in a cell-free system, based on a previously described method (29). After 0.1 mM xanthine was added to the assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 0.3 mM WST-1, and 0.02 U/ml xanthine oxidase) for 15 min at 30°C, the absorbance associated with the O2•−-induced WST-1 reduction was measured at 450 nm.

Measurement of elastase release

Degranulation of azurophilic granules was determined by elastase release. Experiments were performed using MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-p-nitroanilide as the elastase substrate. Briefly, after supplementation with MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-p-nitroanilide (100 μM), neutrophils (6 × 105/ml) were equilibrated at 37°C for 2 min and incubated with FAs for 5 min. Cells were activated by FMLP (100 nM) in the presence of CB (0.5 μg/ml), and changes in absorbance at 405 nm were continuously monitored to determine elastase release. The results are expressed as a percentage of the initial rate of elastase release in the FMLP/CB-activated, drug-free control system.

To assay whether FAs exhibit an inhibitory ability toward elastase activity, a direct elastase activity assay was performed in a cell-free system. Neutrophils (6 × 105/ml) were incubated for 20 min in the presence of FMLP (100 nM)/CB (2.5 μg/ml) at 37°C. Cells were then centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C to collect the elastase from the supernatant. The supernatant was equilibrated at 37°C for 2 min and incubated with or without FAs for 5 min. After incubation, the elastase substrate, MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-p-nitroanilide (100 μM), was added to the reaction mixtures. Changes in absorbance at 405 nm were continuously monitored for 10 min to assay the elastase activity.

Lactate dehydrogenase release

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was determined by a commercially available method (Promega, Madison, WI). Neutrophils (6 × 105/ml) were equilibrated at 37°C for 2 min and incubated with FAs for 15 min. Cytotoxicity was represented by LDH release in a cell-free medium as a percentage of the total LDH released. The total LDH released was determined by lysing cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37°C.

Determination of cAMP concentration

The cAMP level was assayed using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK). The reaction of neutrophils was terminated by adding 0.5% dodecytrimethylammonium bromide. Samples were then centrifuged at 3,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were used as a source for the cAMP samples. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Assay of phosphodiesterase activity

Neutrophils (5 × 107 cells/ml) were sonicated in ice-cold buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.25 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 μM leupeptin, 100 μM PMSF, and 10 μM pepstatin. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min, and then the supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 40 min at 4°C. The cytosolic fraction was used as the source for the phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes. PDE activity was analyzed using a tritium scintillation proximity assay system, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Briefly, assays were performed at 30°C for 10 min in the presence of 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5) containing 8.3 mM MgCl2, 1.7 mM EGTA, and 0.3 mg/ml BSA. Each assay was performed in a 100-μl reaction volume containing the above buffer, the neutrophil supernatant fraction, and around 0.05 μCi [3H]cAMP. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 50 μl PDE scintillation proximity assay beads (1 mg) suspended in 18 mM zinc sulfate. Assays were performed in 96-well microtiter plates. The reaction mixture was allowed to settle for 1 h before counting in a microtiter plate counter.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Neutrophils were loaded with 2 μM fluo 3-AM at 37°C for 45 min. After being washed, cells were resuspended in Ca2+-free HBSS to 3 × 106 cells/ml. In some experiments, neutrophils were suspended in sodium (Na+)-deprived HEPES buffer (124 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.64 mM K2HPO4, 0.66 mM KH2PO4, 5.56 mM dextrose, 10 mM HEPES, and 15.2 mM KHCO3, pH 7.4) (30). The change in fluorescence was monitored using a Hitachi F-4500 spectrofluorometer (Tokyo, Japan) in a quartz cuvette with a thermostat (37°C) and continuous stirring. The excitation wavelength was 488 nm, and the emission wavelength was 520 nm. FMLP, thapsigargin, and A23187 were used to increase [Ca2+]i in the presence or absence of 1 mM Ca2+. [Ca2+]i was calibrated by the fluorescence intensity as follows: [Ca2+]i = Kd × [(F − Fmin)/(Fmax − F)], where F is the observed fluorescence intensity, Fmax and Fmin were respectively obtained by the addition of 0.05% Triton X-100 and 20 mM EGTA, and Kd was taken to be 400 nM.

Measurement of barium influx

Neutrophils were loaded with 4 μM fura 2-AM at 37°C for 45 min. After being washed, cells were resuspended in Ca2+-free HBSS to 3 × 106 cells/ml. The entry of barium (Ba2+) into FMLP- and thapsigargin-stimulated neutrophils was measured, followed by the addition of 1 mM Ba2+ to Ca2+-free medium. Ba2+ uptake was monitored from the increase in fura 2 fluorescence at 510 nm with excitation at 360 nm, which is insensitive to variations in [Ca2+]i (31).

Assay of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase activity

Neutrophils were sonicated in ice-cold Tris buffer (pH 7.4), and then cells were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 40 min at 4°C. The pellet fraction was collected and used as the source of Ca2+-ATPase enzymes. Ca2+-ATPase activity was measured using an assay in which ATP hydrolysis is coupled to NADH oxidation by pyruvate kinase with phosphoenolpyruvate and LDH (32, 33). ATP hydrolysis was measured in 800 μl of relaxation buffer containing 8 × 106 cell equivalents of membrane extract, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 130 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 3 mM ATP, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM NADH, 1.68 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 24 units of pyruvate kinase, 57.6 units of LDH, 10 μM ouabain, and 10 μM thapsigargin at 25°C. Changes in absorbance at 340 nm were continually monitored in a double-beam, six-cell positioner spectrophotometer with constant stirring. After incubation for 5 min, FAs (5 μM) and calmodulin (10 μg/ml) were added to the assay buffer, and the ATPase activity was measured for 50 min. The mmol extinction coefficient for NADH was 6.22. Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) activity was calculated from the slope of the tracing curve between 20 and 35 min and expressed as μmol Pi/1 × 107 cells/h.

Statistical analysis

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated from concentration response curves obtained from several independent experiments using Sigmaplot (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and comparisons were made using Student's t-test. A probability of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

C18 UFAs inhibit O2•− generation and elastase release in FMLP/CB-induced human neutrophils but not in cell-free systems

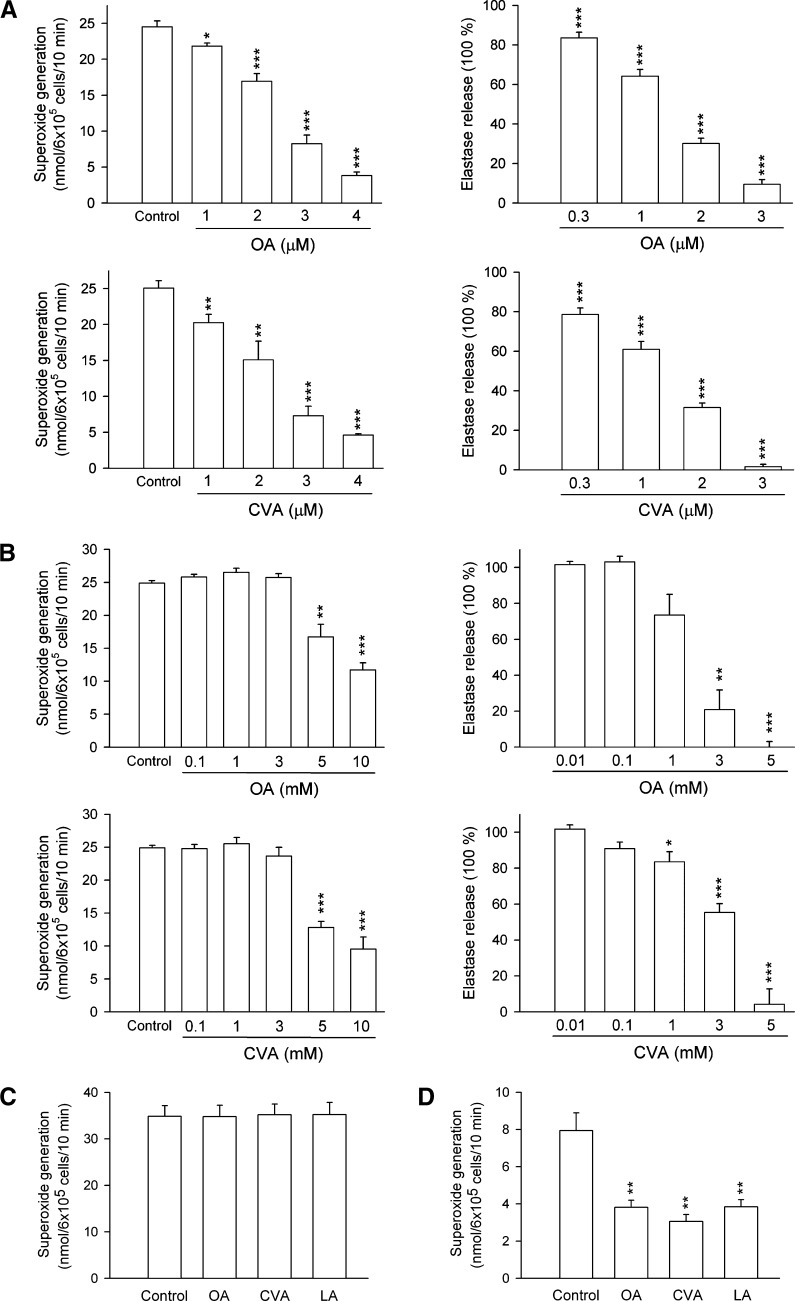

To investigate whether C18 FAs reduced respiratory burst and degranulation by human neutrophils in response to FMLP/CB, the amounts of O2•− and elastase were determined. UFAs significantly inhibited O2•− production and elastase release in FMLP/CB-activated human neutrophils in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 values of <10 μM (Table 1, Fig. 1A). The inhibitory potencies of C18 UFAs were in the order of cis-vaccenic acid (CVA; C18:1n-7) > OA > LA > α-linolenic acid (αLA; C18:3n-3) = γLA > stearidonic acid (C18:4n-3), indicating that the inhibitory actions decreased in the following order: C18:1 > C18:2 > C18:3 > C18:4. Nevertheless, the comparison of data shows that there are no preferences for the double bound position of C18 UFAs on the anti-inflammatory activity. In addition, neither OA methyl ester (OA-me) nor LA-me inhibited these neutrophil functions. The saturated SA (C18:0) at a concentration of 10 μM showed minor effects in human neutrophils. On the other hand, none of these C18 FAs altered the basal O2•− generation or elastase release under resting conditions. Moreover, none of these C18 FAs (up to 30 μM) scavenged O2•− formation or inhibited elastase activity in cell-free systems (data not shown). These data rule out the possibility that the inhibitory effects of C18 UFAs on O2•− release occur through scavenging of O2•− and elastase. Culturing with C18 FAs (up to 10 μM) did not affect cell viability, as assayed by LDH release (data not shown). Moreover, O2•− release induced by PMA (100 nM), a protein kinase C (PKC) activator, was not inhibited by OA, CVA, and LA (5 μM) (Fig. 1C), suggesting that C18 UFAs exert their inhibitory influence by interfering with specific cellular signaling pathways.

TABLE 1.

Effects of C18 FAs on superoxide generation, elastase release, peak intracellular calcium concentrations [Ca2+]i, and the time taken for this concentration to decline to half of its peak values (t1/2) in FMLP-activated neutrophils

| IC50 of C18 FAs |

Effects of C18 FAs at 5 μM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C18 FA | O2•− generation | Elastase Release | Peak [Ca2+]i | t1/2 |

| μM | nM | s | ||

| Control | – | – | 313.19 ± 14.60 | 24.23 ± 1.79 |

| SA | >10 | >10 | 304.68 ± 11.33 | 24.02 ± 1.93 |

| OA (cis, 1n-9) | 2.56 ± 0.13 | 1.40 ± 0.07 | 288.79 ± 15.21 | 8.99 ± 0.86*** |

| CVA (cis, 1n-7) | 2.31 ± 0.20 | 1.36 ± 0.07 | 291.46 ± 22.67 | 10.34 ± 1.24*** |

| LA (cis, 2n-6) | 2.64 ± 0.17 | 1.80 ± 0.12 | 303.39 ± 16.88 | 10.00 ± 0.58*** |

| αLA (cis, 3n-3) | 4.13 ± 0.24 | 3.19 ± 0.25 | 313.22 ± 25.96 | 14.71 ± 1.80** |

| γLA (cis, 3n-6) | 4.57 ± 0.25 | 3.17 ± 0.18 | 303.99 ± 32.34 | 12.30 ± 0.47*** |

| SDA (cis, 4n-3) | 7.98 ± 0.40 | 8.06 ± 0.29 | 311.63 ± 20.59 | 19.28 ± 2.68 |

| OA-me (cis, 1n-9) | >10 | >10 | 309.91 ± 20.67 | 25.62 ± 2.82 |

| LA-me (cis, 2n-6) | >10 | >10 | 301.83 ± 11.02 | 24.55 ± 1.84 |

For all data, values are the mean ± SEM (n = 3–7). *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control. SDA, stearidonic acid; OA-me, OA-methyl ester; LA-me, LA-methyl ester.

Fig. 1.

Effect of C18 UFAs on O2•− generation and elastase release in activated human neutrophils. Human neutrophils were incubated with different concentrations of OA and CVA for 5 min and then activated by FMLP/CB in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 0.1% BSA. C: Human neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), OA, CVA, or LA (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by PMA or thapsigargin/CB (D). O2•− generation and elastase release were induced by FMLP/CB and respectively measured using SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction and by monitoring p-nitroanilide release, as described in Materials and Methods. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3–7). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control.

The effect of C18 UFAs on O2•− generation and elastase release in human neutrophil in the presence of BSA was also investigated to determine whether these FAs could inhibit human neutrophil functions under more physiological condition. As shown in Fig. 1B, FMLP/CB-induced O2•− generation and elastase release were inhibited by higher concentrations (1–10 mM) of OA and CVA in the presence of 0.1% BSA. In addition, OA-me even at higher concentrations (1–10 mM) did not alter FMLP/CB-induced O2•− generation and elastase release in the presence of 0.1% BSA (data not shown). These results indicate that C18 UFAs, essentially when the concentrations exceed the FA binding capacity of albumin, are likely to reduce FMLP/CB-induced O2•− generation and elastase release in human neutrophils.

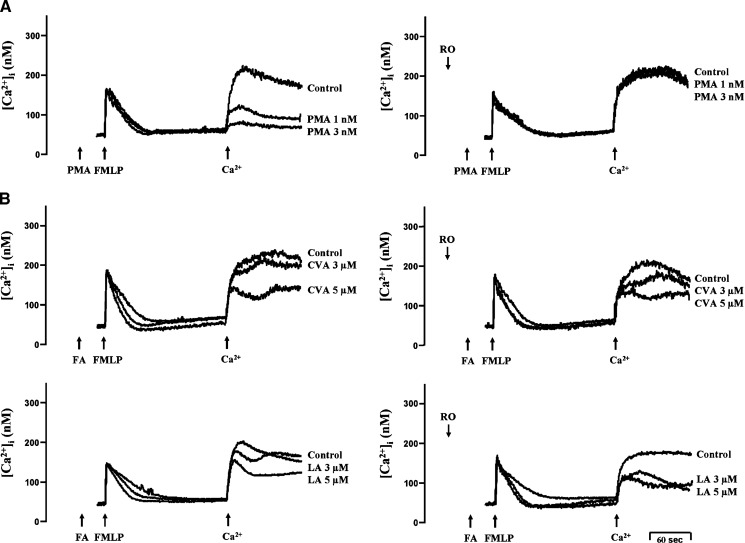

Effects of C18 FAs on [Ca2+]i

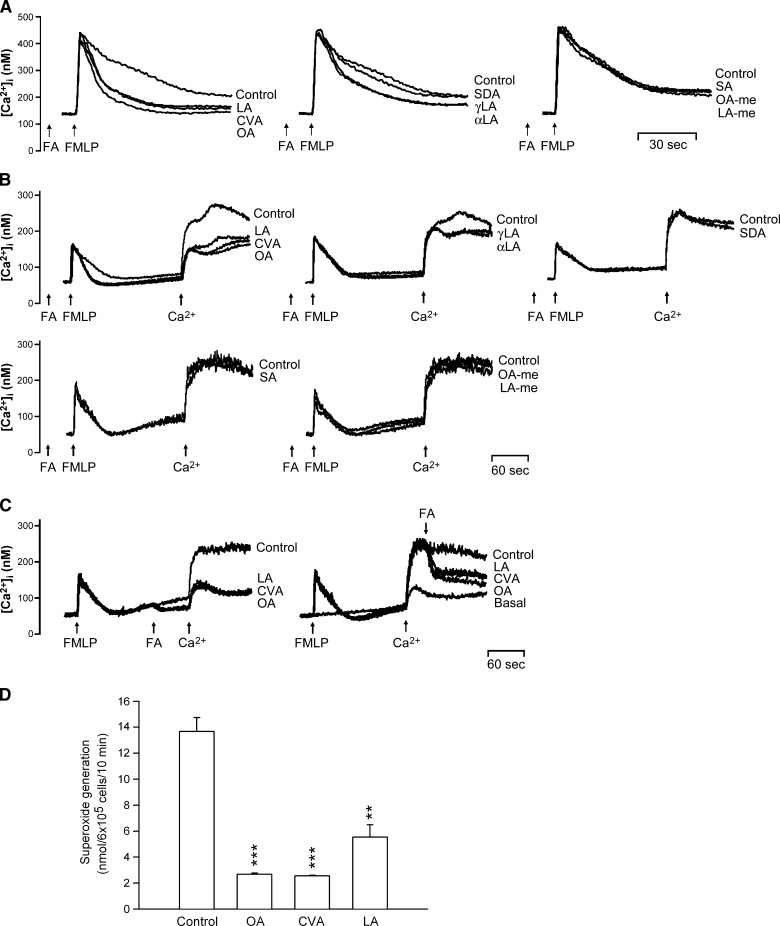

Many cellular functions of neutrophils, such as respiratory burst and degranulation, are regulated by Ca2+ signals (34). None of these C18 FAs (5 μM) affected peak [Ca2+]i values in FMLP-induced cells, but the time it took for [Ca2+]i to return to half of the peak value (t1/2) was significantly shortened by C18 UFAs in a concentration-dependent manner (Table 1, Fig. 2A). Among them, OA, CVA, and LA showed the most potent inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization. In contrast, neither OA-me, LA-me, nor SA affected t1/2 values in FMLP-activated human neutrophils. Additionally, when C18 UFAs were incubated before FMLP in Ca2+-free medium, similar actions on the kinetics of FMLP-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization were obtained. Meanwhile, changes in [Ca2+]i caused by the subsequent addition of 1 mM Ca2+ were inhibited by C18 UFAs (Table 2, Fig. 2B). The latter responses were also confirmed when OA, CVA, and LA were added before or after the reintroduction of Ca2+ (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, OA, CVA, and LA (5 μM) significantly inhibited O2•− production in FMLP/CB-activated human neutrophils in Ca2+-free medium (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Effect of C18 FAs on Ca2+ mobilization and O2•− generation in FMLP-activated human neutrophils. Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control) or FAs (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by 0.1 μM FMLP in 1 mM Ca2+-containing HBSS (A) or in Ca2+-free HBSS followed by the addition of 1 mM Ca2+ (B). C: FAs (5 μM) were treated before or after the reintroduction of 1 mM Ca2+. The traces shown are from four or five different experiments. D: Neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), OA, CVA, or LA (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by FMLP/CB in Ca2+-free HBSS. O2•− generation was measured using SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control.

TABLE 2.

Effects of C18 FAs on peak [Ca2+]i and the time taken for this concentration to decline to half of its peak values (t1/2) in FMLP-activated neutrophils in Ca2+-free HBSS

| FMLP |

Ca2+ |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| C18 FA | Peak [Ca2+]i | t1/2 | Peak [Ca2+]i |

| nM | s | nM | |

| Control | 127.84 ± 15.01 | 30.60 ± 0.91 | 199.42 ± 11.23 |

| SA | 115.27 ± 25.06 | 32.08 ± 0.36 | 191.42 ± 17.48 |

| OA (cis, 1n-9) | 124.01 ± 2.22 | 16.71 ± 1.38 *** | 81.40 ± 6.22 *** |

| CVA (cis, 1n-7) | 118.55 ± 13.96 | 15.23 ± 1.44 *** | 86.33 ± 8.70 *** |

| LA (cis, 2n-6) | 121.57 ± 13.23 | 17.88 ± 2.21 *** | 97.13 ± 13.20 *** |

| αLA (cis, 3n-3) | 117.17 ± 13.21 | 23.52 ± 1.17 ** | 130.84 ± 18.50 * |

| γLA (cis, 3n-6) | 115.71 ± 14.26 | 25.38 ± 0.78 ** | 133.17 ± 13.88 ** |

| SDA (cis, 4n-3) | 123.13 ± 17.65 | 30.64 ± 1.54 | 189.25 ± 15.76 |

| OA-me (cis, 1n-9) | 110.50 ± 7.74 | 30.84 ± 0.36 | 221.47 ± 6.08 |

| LA-me (cis, 2n-6) | 111.61 ± 19.49 | 30.07 ± 1.43 | 199.23 ± 12.57 |

Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control) or FAs (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by 0.1 μM FMLP in Ca2+-free HBSS followed by the addition of 1 mM Ca2+. For all data, values are the mean ± SEM (n = 4–5). *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001 compared with the control.

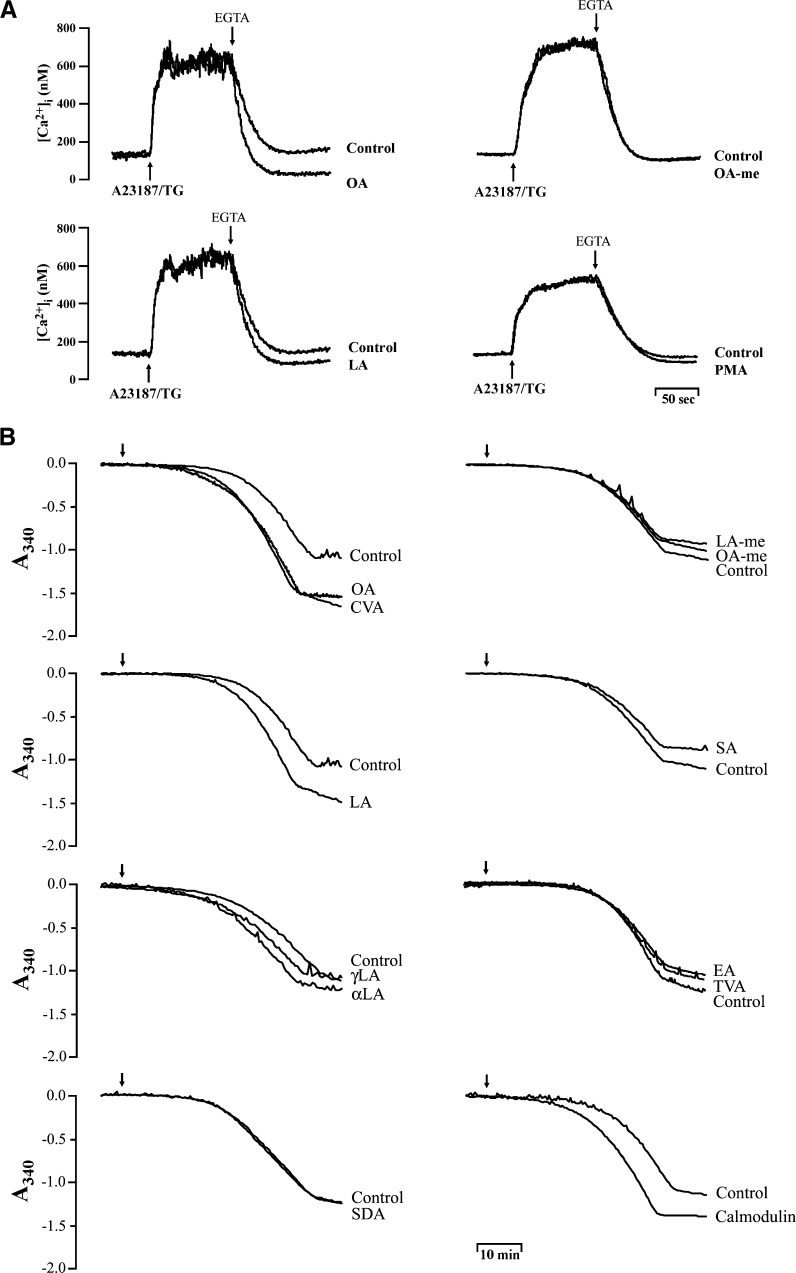

Thapsigargin, a specific and potent inhibitor of ER Ca2+-ATPases (ERCAs), is able to induce the influx of Ca2+ through store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) by blocking ER Ca2+ reuptake, thus elevating [Ca2+]i and depleting ER Ca2+ stores (35). The increase in [Ca2+]i induced by thapsigargin (0.1 μM) was initiated by the slow release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores, which caused considerable and sustained Ca2+ entry. Neither OA, CVA, nor LA (5 μM) affected the initial [Ca2+]i increases but suppressed the sustained [Ca2+]i changes in thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils (Fig. 3A). In line with these data, thapsigargin/CB-induced O2•− generation was moderately reduced by OA, CVA, and LA (5 μM) (Fig. 1D). On the other hand, A23187 is a Ca2+ ionophore that equilibrates Ca2+ gradients across plasma membranes and can cause a rapid rise in [Ca2+]i levels. C18 UFAs showed inhibitory responses toward [Ca2+]i levels induced by lower (20 nM) but not higher concentrations (200 nM) of A23187 (Fig. 3B, C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of C18 UFAs on Ca2+ mobilization in thapsigargin- or A23187-activated human neutrophils. Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control) or FAs (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by 0.1 μM thapsigargin (TG) (A) or 20 (B) or 200 (C) nM A23187 in Ca2+-containing HBSS. The traces shown are from four to six different experiments.

The cAMP pathway is not involved in the inhibitory effects of C18 UFAs

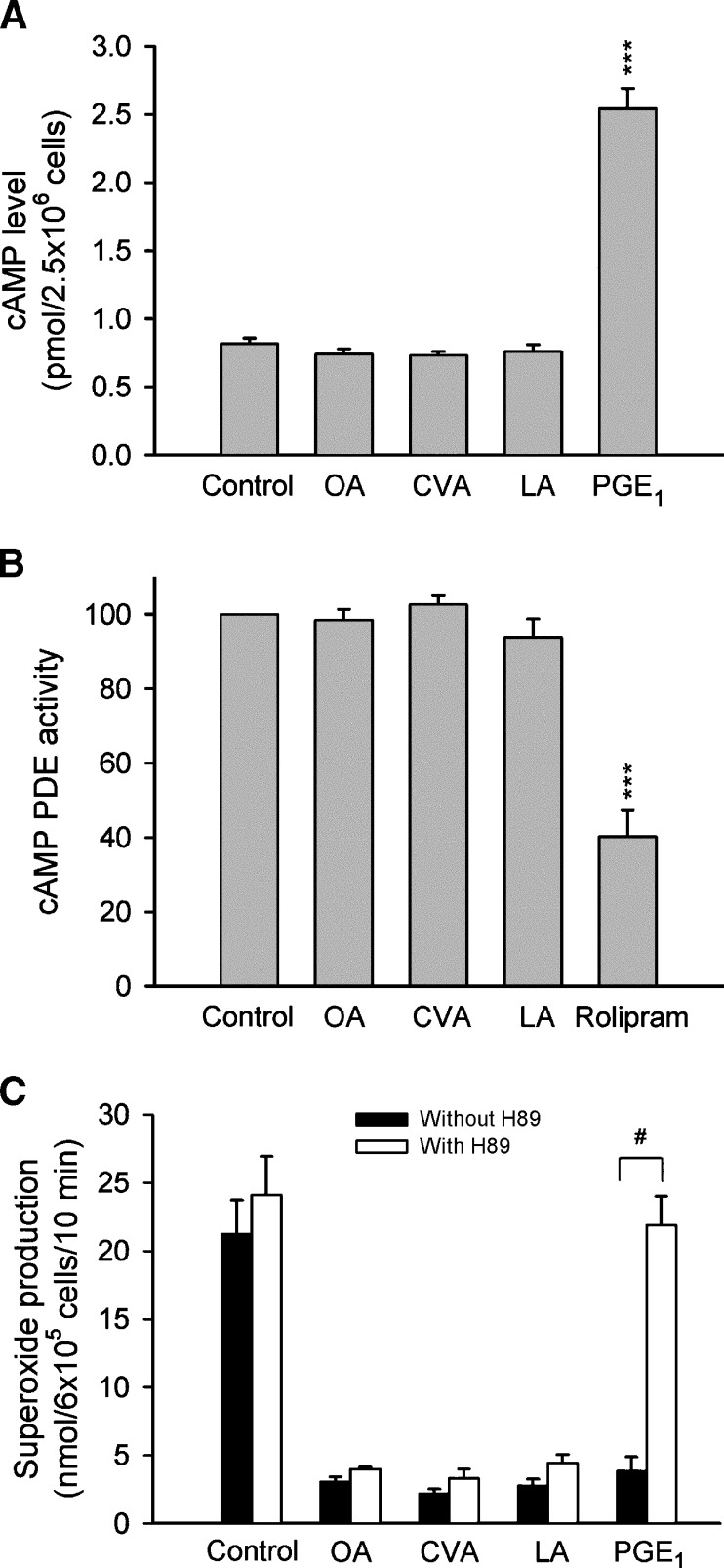

Elevation of intracellular cAMP concentrations has been demonstrated to inhibit the generation of O2•− and the release of elastase, as well as to shorten the value of t1/2 in FMLP-activated human neutrophils (36, 37). To examine whether cAMP pathways are involved in the inhibitory effects of C18 UFAs, cAMP concentrations and PDE activities were assayed. PGE1 (an adenylate cyclase activator) and rolipram (a PDE4 inhibitor) were used as positive controls. Neither cAMP concentrations nor cAMP PDE activities were altered by OA, CVA, or LA (Fig. 4A, B). Moreover, the protein kinase (PK)A inhibitor, H89, did not restore the UFA-induced inhibition of O2•− release (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Effect of C18 UFAs on the cAMP pathway in human neutrophils. A: Neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), FAs (5 μM), or PGE1 (1 μM) for 10 min, and cAMP was assayed using an enzyme immunoassay kit. B: Neutrophil homogenates were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), FAs (5 μM), or rolipram (3 μM), and then 0.05 μCi [3H] cAMP was added to the reaction mixture at 30°C for 10 min. PDE activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. C: O2•− generation was induced by FMLP/CB and measured using SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction. H89 (3 μM) was preincubated for 5 min before the addition of ethanol, FAs, and PGE1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3–4). ***P < 0.001 compared with the control. #P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding PGE1.

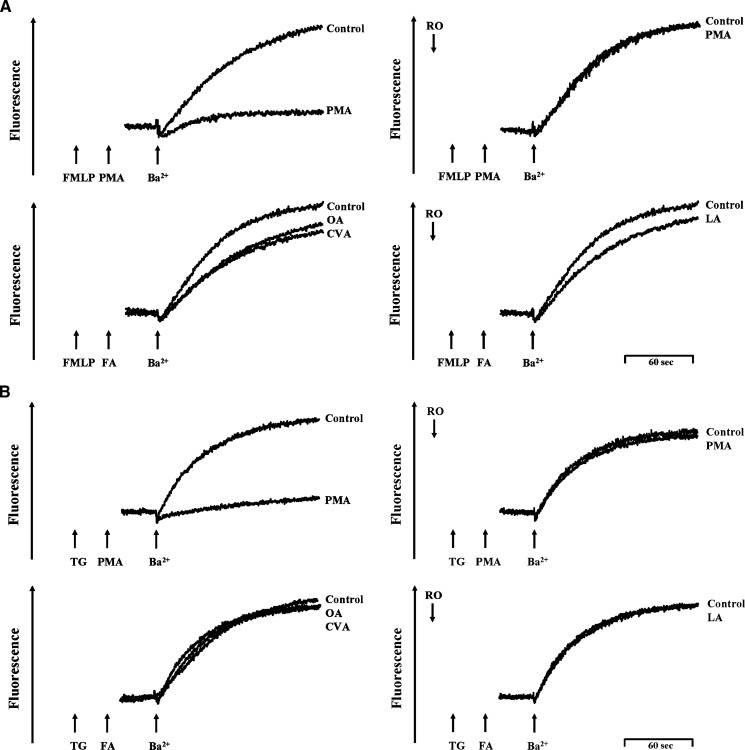

Effects of C18 UFAs and PKC on SOCE

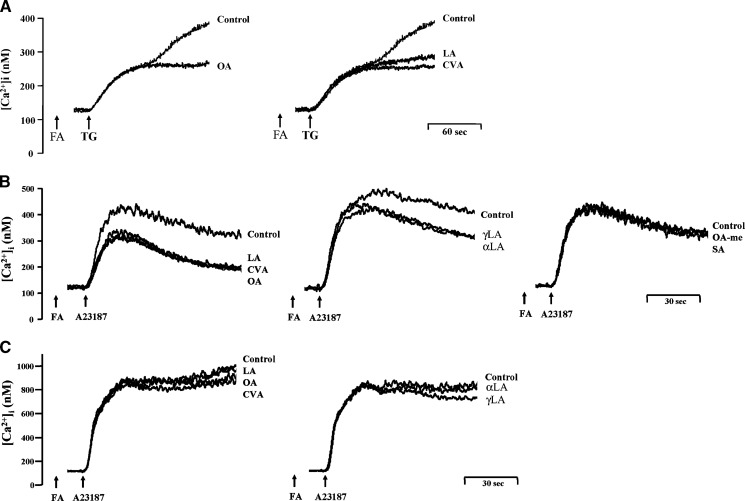

FMLP, via a G-protein-coupled receptor, mobilizes rapid Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive ER Ca2+ stores. Such Ca2+ release depletes ER Ca2+ stores and subsequently initiates Ca2+ entry via SOCE (38, 39). It has been reported that PKC is able to inhibit SOCE in human neutrophils (31). In agreement with this finding, low concentrations of PMA (1 and 3 nM) concentration-dependently inhibited extracellular Ca2+ entry in FMLP-activated human neutrophils, which was completely abolished by the PKC inhibitor, Ro318220 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, Ro318220 failed to alter either CVA- or LA-produced inhibition of extracellular Ca2+ entry (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effect of PMA and C18 UFAs on Ca2+ mobilization in FMLP-activated human neutrophils. Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), PMA (1 and 3 nM) (A), CVA, or LA (3 and 5 μM) (B) for 5 min and then activated by 0.1 μM FMLP in Ca2+-free HBSS followed by the addition of 1 mM Ca2+. Ro318220 (Ro; 1 μM) was preincubated for 3 min before the addition of PMA and FAs. The traces shown are from three or four different experiments.

Effects of C18 UFAs and PKC on extracellular Ba2+ entry

Ba2+, which is not pumped by Ca2+-ATPase either into internal stores or out of the cell, has an affinity for fura-2 (31). Therefore, Ba2+ was used as a Ca2+ surrogate for the Ca2+ entry pathway to trace unidirectional divalent cation movements. FMLP and thapsigargin pretreatment in a Ca2+-free medium and the subsequent addition of 1 mM Ba2+ resulted in an increase in Ba2+ entry. PMA (3 nM) completely inhibited Ba2+ entry in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils, which was abolished by Ro318220 (Fig. 6). These data suggest Ba2+ entry via SOCE in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils. In contrast, OA, CVA, and LA (5 μM) failed to alter the entry of Ba2+ in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effect of C18 UFAs on extracellular Ba2+ entry in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils. Fura 2-loaded neutrophils were stimulated with 0.1 μM FMLP (A) or 0.5 μM thapsigargin (TG) (B) for 3 min in Ca2+-free HBSS followed by supplementation with 1 mM Ba2+, and the fluorescence was monitored at 37°C with stirring. PMA (3 nM) or C18 UFAs (5 μM) were administered 1 min prior to the addition of Ba2+. Ro318220 (Ro; 1 μM) was preincubated for 3 min before activation. The traces shown are from five different experiments.

Effects of Na+ deprivation on the inhibition of C18 UFAs

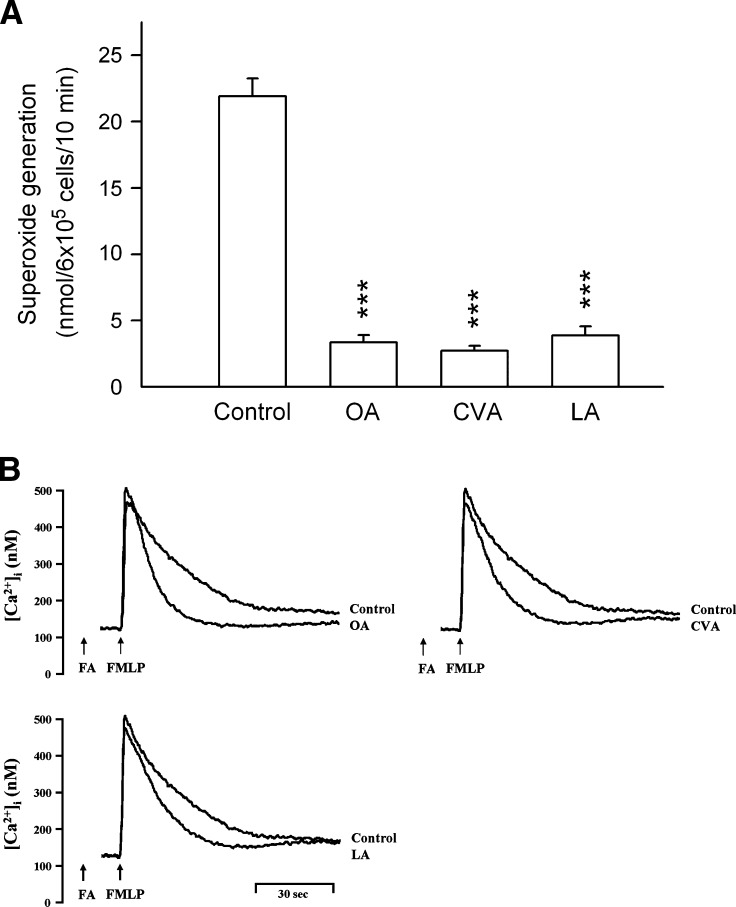

The existence of a Na+-Ca2+ exchange mechanism on the plasma membrane of neutrophils was previously described (40). It is known that the plasma membrane Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) plays a role in removing Ca2+ from the cytosol. To examine whether the NCX is involved in the inhibitory effects of C18 UFAs, experiments were carried out in Na+-free solutions to avoid a possible contribution of the NCX. As shown in Fig. 7, OA, CVA, and LA (5 μM) significantly inhibited O2•− production and shortened the value of t1/2 in FMLP-activated human neutrophils in Ca2+-containing Na+-deprived medium, suggesting that the role of the NCX can be excluded.

Fig. 7.

Effect of C18 UFAs on O2•− production and Ca2+ mobilization in FMLP-activated human neutrophils in Ca2+-containing Na+-deprived medium. A: Human neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), OA, CVA, or LA (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by FMLP/CB. O2•− generation was measured using SOD-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *** P < 0.001 compared with the control. B: Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were incubated with ethanol (0.1%, control), OA, CVA, or LA (5 μM) for 5 min and then activated by 0.1 μM FMLP in Ca2+-containing Na+-deprived medium. The traces shown are from four or five different experiments.

Effects of C18 FAs on PMCA activity

Calcium homeostasis is maintained through a balance between cell membrane permeability and the energy-dependent transport of Ca2+ by Ca2+-ATPase at the level of the cell membrane and at the level of ER. To address the effects of C18 UFAs on PMCA pumps, PMCA activity was assayed in human neutrophils as previously described (30) with some modifications. Neutrophils were preincubated with thapsigargin (0.5 μM) and A23187 (0.2 μM) to inhibit ERCA and induce Ca2+ entry in Na+-deprived medium containing carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (1 μM) and oligomycin A (1 μM) to prevent mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and to inhibit ATP-utilizing and -generating systems. After this treatment, an extensive increase in [Ca2+]i was observed, and then EDTA (1 mM) was added to remove the external Ca2+ evoking a decline in [Ca2+]i due to Ca2+ clearance by PMCA, which was inhibited by calmidazolium (5 μM), a calmodulin inhibitor (data not shown). Under these conditions, the clearance rate of [Ca2+]i was enhanced by OA and LA from 626.49 ± 29.96 (control) to 758.56 ± 13.67 (P < 0.01) and 725.80 ± 27.64 nM/min (P < 0.01), respectively. Additionally, OA-me and PMA failed to modify the clearance rate of [Ca2+]i in this assay (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Effect of C18 FAs on PMCA activity in human neutrophils and in isolated neutrophil membranes. A: Fluo 3-loaded neutrophils were stimulated with thapsigargin (TG; 0.5 μM) plus A23187 (0.2 μM), and subsequently EGTA (1 mM) was added in combination with FAs (5 μM) or PMA (3 nM) in Ca2+-containing Na+-deprived medium supplemented with oligomycin A (1 μM) and CCCP (1 μM). B: PMCA activity of neutrophil membranes was measured using a coupled enzyme assay in the presence of ouabain (10 μM) and thapsigargin (10 μM) as described in Materials and Methods. The indicated FAs (5 μM) and calmodulin (10 μg/ml) were added to the assay buffer, and the ATPase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 340 nm for 50 min at 25°C with stirring. The traces shown are from four or seven different experiments.

The effects of C18 FAs on PMCA activities were further tested by determining ATPase activities in neutrophil membrane fractions in the presence of thapsigargin and ouabain to inhibit ERCA and Na+/K+ ATPase. The removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol is maintained through an energy-dependent process. Since no ATP hydrolysis was observed when the plasma membrane was subtracted, the results suggest that the difference in the rate of ATP hydrolysis in the presence or absence of C18 FAs results through modulation of ATPase activity in the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 8B, the activities of PMCA were significantly enhanced by C18 mono- and bi-UFAs and by calmodulin. OA, CVA, LA, and calmodulin enhanced the activities of ATPase from 0.39 ± 0.03 (control) to 0.65 ± 0.02 (P < 0.001), 0.62 ± 0.06 (P < 0.01), 0.58 ± 0.05 (P < 0.01), and 0.58 ± 0.02 μmol Pi/1 × 107 cells/h (P < 0.001), respectively. In contrast, the C18 saturated FA and esterified UFAs had no effect on PMCA activities (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, a cellular model of isolated human neutrophils was established to elucidate the anti-inflammatory functions of linear-chain C18 FAs. Our data show that C18 UFAs potently inhibited the generation of O2•− and the release of elastase in FMLP-activated human neutrophils in a concentration-dependent fashion with IC50 values of <10 μM. The inhibitory potency decreased with an increasing number of double bonds in C18 UFAs. When the carboxy group of C18 mono- or bi-UFA was chemically modified by adding a methyl ester, however, these C18 UFAs did not exhibit inhibition. In addition, the C18 saturated FA caused no effect on human neutrophil responses. Multiple observations made in the study suggest that C18 UFAs suppress respiratory burst and degranulation of human neutrophils through an increase in the clearance of cytosolic Ca2+.

It is well established that Ca2+ signaling is a key second messenger regulating neutrophil functions (34). Consistent with this, BAPTA-AM, a cell-permeable Ca2+ chelator, inhibited the generation of O2•− and the release of elastase in FMLP-activated human neutrophils (data not shown). Interestingly, C18 UFAs did not alter FMLP-induced peak [Ca2+]i values but accelerated the rate of decline in [Ca2+]i. Clearly, the potency of C18 FAs of attenuating [Ca2+]i is correlated with decreasing O2•− generation and elastase release. These results suggest that the inhibitory effects of C18 UFAs are mediated through a blockade of Ca2+ signaling pathways. Furthermore, C18 UFAs with a free carboxyl end, added before or after FMLP, suppressed changes in [Ca2+]i caused by the subsequent addition of Ca2+. These data indicate that the inhibition of [Ca2+]i by C18 UFAs is not through alteration of the IP3 signaling pathway. In line with this, C18 UFAs, OA, CVA, and LA, suppressed the sustained [Ca2+]i changes in thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils. Moreover, thapsigargin-induced O2•− generation was reduced by OA, CVA, and LA.

Calcium homeostasis is maintained through a complex set of mechanisms that controls cellular Ca2+ influx and efflux as well as intracellular Ca2+ stores. Because of this critical dependence of activation of the proinflammatory activities of neutrophils on Ca2+, the mechanisms used by these cells to both mobilize and dispose of Ca2+ have been identified as potential targets for anti-inflammatory agents (34). We previously reported that cAMP-elevating agents can accelerate Ca2+ clearance from the cytosol as well as inhibit the generation of O2•− and the release of elastase in FMLP-activated human neutrophils (36, 37). This contention is supported by a previous study, which reported that cAMP/protein kinase A increases the Ca2+ sequestering/resequestering activity of ERCA by phosphorylation of the regulatory polypeptide, phospholamban (41). In this study, however, we show that pretreatment with a protein kinase A inhibitor did not restore the UFA-induced inhibition of O2•− release, suggesting that a cAMP-dependent pathway is not involved in the inhibition of C18 UFAs. Consistent with this result, C18 mono-, bi-, and tri-UFAs failed to elevate the concentrations of cAMP or to alter the activities of cAMP-specific PDEs.

Murakami, Chan, and Routtenberg (42) reported that OA and LA, but not SA, activate PKC independently of Ca2+ and phospholipids. Moreover, PKC has been shown to inhibit SOCE in human neutrophils (31). Interestingly, a similar effect of regulating FMLP-induced [Ca2+]i changes in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ was obtained with C18 UFAs and PMA. PMA, at low concentrations of 1 and 3 nM, did not significantly affect the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, but this agent hastened the rate of decline in [Ca2+]i of FMLP-activated human neutrophils (data not shown). On the basis of these results, it is possible to postulate that the C18 UFA-induced [Ca2+]i decrease was mediated by activation of PKC and inhibition of SOCE. Our data confirmed that PMA concentration-dependently inhibited extracellular Ca2+ and Ba2+ entry in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils, which was completely abolished by Ro318220, a PKC inhibitor. Nevertheless, a role for PKC in C18 UFA-mediated inhibition was ruled out because the C18 UFA-inhibited extracellular Ca2+ entry in FMLP-activated neutrophils was not reversed by a PKC inhibitor. Indeed, C18 UFAs failed to alter extracellular Ba2+ entry in FMLP- and thapsigargin-activated human neutrophils, indicating that C18 UFAs are unable to inhibit the SOCE pathway.

The rate of decline in [Ca2+]i is governed by the efficiency of clearance of Ca2+ from the cytosol and by the regulation of the time of onset, rate, and magnitude of the influx of extracellular cations (34). The C18 UFA-induced [Ca2+]i decrease was not due to inhibition of Ca2+ entry; thus, we propose that this effect should be due to stimulation of Ca2+ efflux. A23187 is a Ca2+ ionophore that equilibrates Ca2+ gradients across plasma membranes and can cause a rapid rise in [Ca2+]i levels. Interestingly, C18 UFAs caused inhibitory responses in [Ca2+]i levels induced by lower but not higher concentrations of A23187, suggesting that the inhibitory actions of C18 UFAs are attenuated by high rates of extracellular Ca2+ influx. The efflux of Ca2+ from the cytosol is mediated by the NCX and PMCA in activated human neutrophils. Inhibition of FMLP-activated O2•− production and Ca2+ entry by C18 UFAs was obtained in both normal and Na+-deprived media; therefore, there is no indication that C18 UFAs act via promoting NCX activity on the plasma membrane. PMCA is known to be important for Ca2+ homeostasis in most cells. PMCA represents a high-affinity system for the expulsion of Ca2+ from cells and is responsible for long-term setting and maintenance of [Ca2+]i levels (43, 44). PMCA pumps are stimulated by calmodulin in the presence of Ca2+ (45). Moreover, PMCA activity is also influenced by the membrane lipid composition and structure (33). Adamo et al. (46) suggested that acidic phospholipids activate PMCA by interacting with an independent acidic lipid-responsive region. This study showed that the activities of PMCA were significantly enhanced by C18 mono- and bi-UFAs activated human neutrophils and in isolated neutrophil membranes. Consistent with these results, it was reported that purified PMCA of erythrocyte membranes can be activated by the C18 UFAs, OA and LA (47). Our results show that the increasing potency of C18 FAs on PMCA activities appears to be correlated with decreases in O2•− generation and elastase release as well as the accelerated clearance of [Ca2+]i in human neutrophils. Similarly, Oda et al. (48) reported that both the free carboxy group and the number of double bonds of the C18 UFA structure are important in providing a potent telomerase-inhibitory effect. The three-dimensional structure of the telomerase active site appears to have a pocket that could bind OA (48). It is obvious that an analysis of the binding sites of C18 UFAs on PMCA and telomerase will be critical in clarifying the molecular mechanism of C18 UFAs.

Although the effect of C18 FAs on human neutrophil functions has been studied extensively, several points remain to be fully established, as some authors have found an increase (13–17), whereas others have found a decrease (18, 19), in ROS generation, CD11b expression, leukotriene B4 production, enzyme release, and/or phagocytosis by neutrophils in response to C18 FA treatment. Contradictory observations reported in previous studies may in part be the result of different concentrations and methods used to determined neutrophil functions. For example, OA and LA at high concentrations (100 and 1,000 μM) induced ROS production by themselves, whereas both C18 UFAs at low concentrations (1–10 μM) inhibited FMLP-activated ROS release in human neutrophils (20). Furthermore, we found that exposure of human neutrophils to high concentrations (30 and 50 μM) of C18 FAs caused a concentration-dependent increase in LDH release (data not shown). Additionally, Hatanaka et al. (14) showed that OA, LA, and γLA at high concentrations (50 and 100 μM) per se lead to cytochrome c reduction. Our data indicate that C18 UFAs significantly suppressed O2•− generation and elastase release in activated human neutrophils in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 values of <10 μM. Activated neutrophils that produce ROS and granule proteases are involved in oxidative stress and inflammation. Alterations in dietary levels of C18 UFAs have significant clinical benefits in cardiovascular diseases and inflammatory syndromes (8–12). LA, αLA, and γLA are thought to have important functions in preventing and treating coronary artery disease and rheumatoid arthritis (8, 12). However, Juttner et al. (49) showed that parenteral nutrition containing OA and LA can induce O2•− generation of neutrophils. Obviously, further research is needed to clarify the effects of C18 UFAs in neutrophil functions before the therapeutic potential of C18 UFAs in inflammation can be realized.

In conclusion, this study shows that C18 UFAs inhibit human neutrophil proinflammatory responses, including respiratory burst, degranulation, and Ca2+ mobilization. These anti-neutrophilic inflammatory effects are mediated through the elevation of the PMCA activity. Also, our results suggest that both the free carboxy group and the number of double bonds of the C18 UFA structure are critical in providing the potent inhibitory effects in human neutrophils.

Abbreviations

Ba2+, barium

C18, 18-carbon

CB, cytochalasin B

CVA, cis-vaccenic acid

ER, endoplasmic reticulum

ERCA, endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

FMLP, formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine

IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration

IP3, 1,4,5-triphosphate

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

LA, linoleic acid

αLA, α-linoleic acid

γLA, γ-linoleic acid

NCX, Na+-Ca2+ exchanger

OA, oleic acid

O2•−, superoxide anion

PDE, phosphodiesterase

PKC, protein kinase C

PMA, phorbol myristate acetate

PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase

ROS, reactive oxygen species

SA, stearic acid

SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry

SOD, superoxide dismutase

UFA, unsaturated fatty acid

This work was supported by grants from the Chang Gung Medical Research Foundation and the National Science Council, Taiwan. The authors disclose that there is no conflict of interest.

Published, JLR Papers in Press, March 17, 2009.

References

- 1.Martins de Lima T., R. Gorjao, E. Hatanaka, M. F. Cury-Boaventura, E. P. Portioli Silva, J. Procopio, and R. Curi. 2007. Mechanisms by which fatty acids regulate leucocyte function. Clin. Sci. 113 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schönfeld P., and L. Wojtczak. 2008. Fatty acids as modulators of the cellular production of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorjao R., S. M. Hirabara, T. M. de Lima, M. F. Cury-Boaventura, and R. Curi. 2007. Regulation of interleukin-2 signaling by fatty acids in human lymphocytes. J. Lipid Res. 48 2009–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leaf A., C. M. Albert, M. Josephson, D. Steinhaus, J. Kluger, J. X. Kang, B. Cox, H. Zhang, and D. Schoenfeld. 2005. Prevention of fatal arrhythmias in high-risk subjects by fish oil n-3 fatty acid intake. Circulation. 112 2762–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connor K. M., J. P. SanGiovanni, C. Lofqvist, C. M. Aderman, J. Chen, A. Higuchi, S. Hong, E. A. Pravda, S. Majchrzak, D. Carper, et al. 2007. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 13 868–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sierra S., F. Lara-Villoslada, M. Comalada, M. Olivares, and J. Xaus. 2008. Dietary eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid equally incorporate as decosahexaenoic acid but differ in inflammatory effects. Nutrition. 24 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaikh S. R., and M. Edidin. 2007. Immunosuppressive effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids on antigen presentation by human leukocyte antigen class I molecules. J. Lipid Res. 48 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djousse L., J. S. Pankow, J. H. Eckfeldt, A. R. Folsom, P. N. Hopkins, M. A. Province, Y. Hong, and R. C. Ellison. 2001. Relation between dietary linolenic acid and coronary artery disease in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 74 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horrobin D. F. 1992. Nutritional and medical importance of gamma-linolenic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 31 163–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James M. J., R. A. Gibson, and L. G. Cleland. 2000. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory mediator production. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71 343S–348S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziboh V. A., S. Naguwa, K. Vang, J. Wineinger, B. M. Morrissey, M. Watnik, and M. E. Gershwin. 2004. Suppression of leukotriene B4 generation by ex-vivo neutrophils isolated from asthma patients on dietary supplementation with gammalinolenic acid-containing borage oil: possible implication in asthma. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 11 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal L. J., E. G. Boyce, and R. B. Zurier. 1993. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with gammalinolenic acid. Ann. Intern. Med. 119 867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates E. J., A. Ferrante, L. Smithers, A. Poulos, and B. S. Robinson. 1995. Effect of fatty acid structure on neutrophil adhesion, degranulation and damage to endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 116 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatanaka E., A. C. Levada-Pires, T. C. Pithon-Curi, and R. Curi. 2006. Systematic study on ROS production induced by oleic, linoleic, and gamma-linolenic acids in human and rat neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41 1124–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mastrangelo A. M., T. M. Jeitner, and J. W. Eaton. 1998. Oleic acid increases cell surface expression and activity of CD11b on human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 161 4268–4275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serezani C. H., D. M. Aronoff, S. Jancar, and M. Peters-Golden. 2005. Leukotriene B4 mediates p47phox phosphorylation and membrane translocation in polyunsaturated fatty acid-stimulated neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78 976–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanten G. J., F. P. Janssen, and A. H. Naber. 2002. Saturated triglycerides and fatty acids activate neutrophils depending on carbon chain-length. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 32 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akamatsu H., J. Komura, Y. Miyachi, Y. Asada, and Y. Niwa. 1990. Suppressive effects of linoleic acid on neutrophil oxygen metabolism and phagocytosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 95 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higazi A. al-R., and I. I. Barghouti. 1994. Regulation of neutrophil activation by oleic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1201 442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heiskanen K., M. Ruotsalainen, and K. Savolainen. 1995. Interactions of cis-fatty acids and their anilides with formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, phorbol myristate acetate and dioctanoyl-s,n-glycerol in human leukocytes. Toxicology. 104 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown K. A., S. D. Brain, J. D. Pearson, J. D. Edgeworth, S. M. Lewis, and D. F. Treacher. 2006. Neutrophils in development of multiple organ failure in sepsis. Lancet. 368 157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gach O., M. Nys, G. Deby-Dupont, J. P. Chapelle, M. Lamy, L. A. Pierard, and V. Legrand. 2006. Acute neutrophil activation in direct stenting: comparison of stable and unstable angina patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 112 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehr H. A., M. D. Menger, and K. Messmer. 1993. Impact of leukocyte adhesion on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: conceivable mechanisms and proven facts. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 121 539–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans B. J., D. O. Haskard, J. R. Finch, I. R. Hambleton, R. C. Landis, and K. M. Taylor. 2008. The inflammatory effect of cardiopulmonary bypass on leukocyte extravasation in vivo. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 135 999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathan C. 2006. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacy P., and G. Eitzen. 2008. Control of granule exocytosis in neutrophils. Front. Biosci. 13 5559–5570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham C. T. 2006. Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6 541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berridge M. J. 1993. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 361 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang T. L., Y. C. Wu, S. H. Yeh, and R. Y. Kuo. 2005. Suppression of respiratory burst in human neutrophils by new synthetic pyrrolo-benzylisoquinolines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 69 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J. P., Y. S. Chen, C. R. Tsai, L. J. Huang, and S. C. Kuo. 2004. The blockade of cyclopiazonic acid-induced store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway by YC-1 in neutrophils. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68 2053–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montero M., J. Garcia-Sancho, and J. Alvarez. 1993. Transient inhibition by chemotactic peptide of a store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 268 13055–13061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scharschmidt B. F., E. B. Keeffe, N. M. Blankenship, and R. K. Ockner. 1979. Validation of a recording spectrophotometric method for measurement of membrane-associated Mg- and NaK-ATPase activity. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 93 790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang D., W. L. Dean, D. Borchman, and C. A. Paterson. 2006. The influence of membrane lipid structure on plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase activity. Cell Calcium. 39 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tintinger G., H. C. Steel, and R. Anderson. 2005. Taming the neutrophil: calcium clearance and influx mechanisms as novel targets for pharmacological control. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 141 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucas M., and P. Diaz. 2001. Thapsigargin-induced calcium entry and apoptotic death of neutrophils are blocked by activation of protein kinase C. Pharmacology. 63 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang T. L., Y. L. Leu, S. H. Kao, M. C. Tang, and H. L. Chang. 2006. Viscolin, a new chalcone from Viscum coloratum, inhibits human neutrophil superoxide anion and elastase release via a cAMP-dependent pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang T. L., S. H. Yeh, Y. L. Leu, C. Y. Chern, and H. C. Hsu. 2006. Inhibition of superoxide anion and elastase release in human neutrophils by 3′-isopropoxychalcone via a cAMP-dependent pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 148 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itagaki K., K. B. Kannan, D. H. Livingston, E. A. Deitch, Z. Fekete, and C. J. Hauser. 2002. Store-operated calcium entry in human neutrophils reflects multiple contributions from independently regulated pathways. J. Immunol. 168 4063–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Putney J. W., Jr. 1986. A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 7 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simchowitz L., and E. J. Cragoe, Jr. 1988. Na+-Ca2+ exchange in human neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. 254 C150–C164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu G., J. W. Lester, K. B. Young, W. Luo, J. Zhai, and E. G. Kranias. 2000. A single site (Ser16) phosphorylation in phospholamban is sufficient in mediating its maximal cardiac responses to beta-agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 275 38938–38943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murakami K., S. Y. Chan, and A. Routtenberg. 1986. Protein kinase C activation by cis-fatty acid in the absence of Ca2+ and phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 261 15424–15429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Leva F., T. Domi, L. Fedrizzi, D. Lim, and E. Carafoli. 2008. The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase of animal cells: structure, function and regulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castillo K., R. Delgado, and J. Bacigalupo. 2007. Plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase in the cilia of olfactory receptor neurons: possible role in Ca(2+) clearance. Eur. J. Neurosci. 26 2524–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monesterolo N. E., V. S. Santander, A. N. Campetelli, C. A. Arce, H. S. Barra, and C. H. Casale. 2008. Activation of PMCA by calmodulin or ethanol in plasma membrane vesicles from rat brain involves dissociation of the acetylated tubulin/PMCA complex. FEBS J. 275 3567–3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adamo H. P., T. Pinto Fde, L. M. Bredeston, and G. R. Corradi. 2003. Acidic-lipid responsive regions of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 986 552–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niggli V., E. S. Adunyah, and E. Carafoli. 1981. Acidic phospholipids, unsaturated fatty acids, and limited proteolysis mimic the effect of calmodulin on the purified erythrocyte Ca2+- ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 256 8588–8592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oda M., T. Ueno, N. Kasai, H. Takahashi, H. Yoshida, F. Sugawara, K. Sakaguchi, H. Hayashi, and Y. Mizushina. 2002. Inhibition of telomerase by linear-chain fatty acids: a structural analysis. Biochem. J. 367 329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Juttner B., J. Kroplin, S. M. Coldewey, L. Witt, W. A. Osthaus, C. Weilbach, and D. Scheinichen. 2008. Unsaturated long-chain fatty acids induce the respiratory burst of human neutrophils and monocytes in whole blood. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 5 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]