Abstract

Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma (EES) is a branch of neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), which is very rare soft tissue sarcoma. We report a case of EES/PNET arising is the lung of a 67-yr-old man. Computed tomography, bone scintigraphy, and positron emission tomography confirmed the mass to have a primary pulmonary origin. The mass showed positive reactivity in the Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stain and MIC-2 immunoreactivity in immunohistochemical stain. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed, which revealed an EWSR1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1) 22q12 rearrangement. The diagnosis was confirmed both pathologically and genetically. The mass lesion was resected, and the patient is currently undergoing chemotherapy.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Ewing's, Neuroectodermal Tumors, Primitive, Peripheral, Lung

INTRODUCTION

Ewing's sarcoma is a relatively rare malignant bone neoplasm that usually occurs in children and young adults and involves the major long bones, pelvis, and ribs. However, primary pulmonary Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET) is extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, only eight cases of primary pulmonary ES/PNET have been reported in the literature (1-4).

CASE REPORT

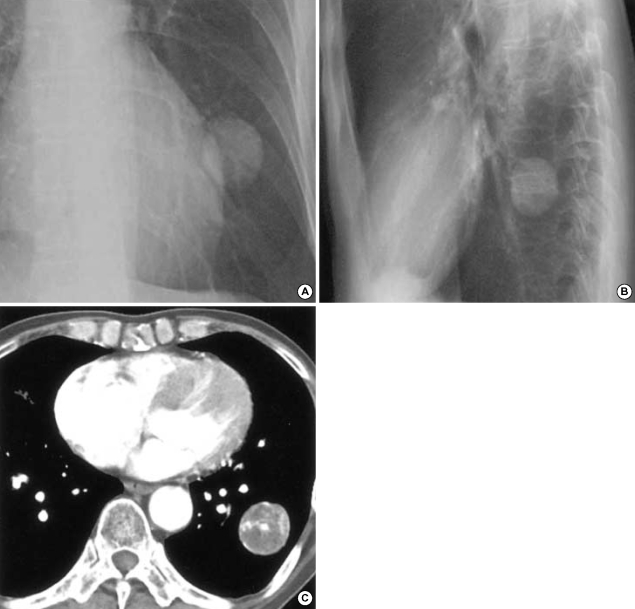

A 67-yr-old man visited with a lung mass that had been detected incidentally on chest roentgenogram taken during the national insurance screening program. The chest PA and left lateral films revealed an approximately 4-cm sized well-defined mass at the left lower lobe (Fig. 1A, B). Computed tomography showed a mass with a smooth margin and the tumor had well enhanced linear opacity inside of the contrast enhancement. The mass was not connected to the pleurae, chest walls, or other adjacent organs (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

(A, B) An approximately 4 cm round solitary mass is shown at the left lower lung field on posterior-anterior and left lateral chest roentgenograms. (C) The chest CT scan showing a heterogeneously contrast-enhancing mass lesion in the left lung.

The origin of the mass and metastasis was verified by examining the whole body bone scan, PET/CT scan with 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG), and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). On bone scan, there were no active skeletal lesions. Neither the kidney nor soft tissue showed any abnormal uptake. The FDG-PET scan revealed intense and homogenous hypermetabolic activity with a metabolic defect at the left lower lobe of the lung. The 1-hr maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) was 6.22. Except for the lung lesion, there was no abnormal hypermetabolic lesions or metabolic defects. Therefore we confirmed the lung was the primary focus of the mass, and there were no distant metastases.

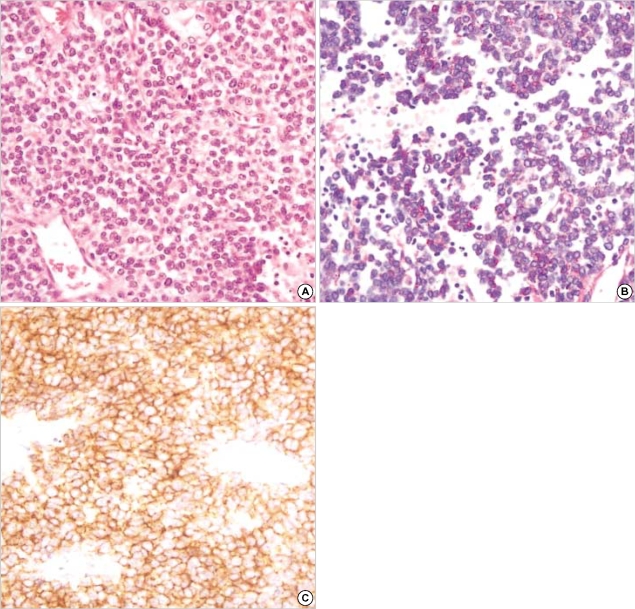

A percutaneous needle biopsy was performed with 19 G thru cut needle under fluoroscopic guidance. Hematoxylin and eosin (H-E) staining showed a solidly packed round cell pattern with a striking uniformity. The individual cells had a small round to ovoid nucleus with a distinctly unclear membrane, fine powdery chromatin, and one or two minute nucleoli. The cytoplasm was ill-defined, scanty, and pale stained (Fig. 2A). Some of the cells had irregularly vacuolated cytoplasm secondary to glycogen deposition, which was positive for Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stain (Fig. 2B). The tumor cells showed a strong membranous MIC-2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) Light microscopy of the tumor shows uniformly solidly packed round cells with a distinct unclear membrane (H&E, ×400). (B) Irregularly vacuolated cytoplasm secondary to glycogen deposition (PAS, ×400). (C) Strong membranous MIC2 immunoreactivity (LSAB, ×400).

The other markers including cytokeratin (CK), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), chromogranin, CK7, CK19, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) were all negative. Vimentin, synaptophysin, and p63 stained focally, and more than 90% of the cells were positive for Ki-67 labeling. All the pathological findings were compatible with a ES/PNET of primary pulmonary origin.

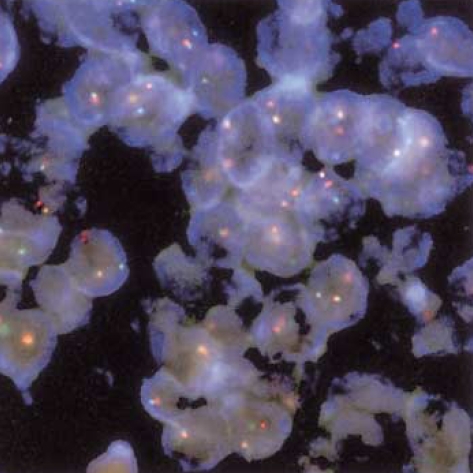

After pathological diagnosis, surgical resection of the left lower lobe of the lung was done. Serial sections of the lung showed that the cut surface had a well demarcated round whitish soft mass, which had extensive tumoral necrosis. The mass was not connected to the bronchi or vessels. It was 5 cm apart from the nearest bronchial resection margin and 0.5 cm from the nearest visceral pleura (Fig. 3). Using the tissue obtained after surgical resection, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed using the LSI® Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) 22q12 Dual Color Break Apart Rearrangement Probe and revealed EWSR1 22q12 rearrangement in 82% (164 out of 200 cells) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Well demarcated whitish soft tissue mass having extensive tumoral necrosis inside.

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed EWSR1 22q12 rearrangement detected by using LSI® EWSR1 (22q12) Dual Color Break-Apart Rearrangement probe.

Ultimately, the diagnosis was established to be a 4-cm sized ES/PNET arising primarily from the lung with no regional invasion to the bronchi, visceral, or parietal pleurae. In addition, there was no perihilar lymph node invasion (all 4 of 4) or distant metastasis. After surgery, the patient was administered with combination chemotherapy with vincristin, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide.

DISCUSSION

Since the first description of ES and extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma by James Ewing and Tefft et al., these two conditions have been confused histologically with other small cell tumors, including PNET (5, 6), but recent immunoperoxidase and cytogenic studies indicated that PNET and ES are the same entity showing varying degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation, and they were categorized into a group known as the Ewing family of tumors (7). The ES/PNET family is an uncommon malignant neoplasm, and shares common histological features of closely packed small primitive round cells. It most often arises in the soft tissues and bones but has rarely been reported in other sites, such as the ovary, testis, uterus, kidney, pancreas, palate, myocardium, and lung (1, 7-10). The morphological features of intrapulmonary tumors are similar to those of the ES/PNET in a variety of other locations. In this case the patient was 67 yr old, which was an unusual age compared with previously reported ES/PNET cases. Most of them were from child to young adults except one case (4).

The diagnosis of a tumor is made using several modalities such as light microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and cytogeneteics (1). Immunohistochemical and histochemical staining positive for glycogen (PAS, 80%), neuron-specific enolase (60%), S-100 protein (50%), and MIC-2 marker (90%), as well as negative findings for leukocyte common antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratin, desmin, vimentin, myoglobin, and glial fibrillary acidic protein are indicative of ES/PNET (11, 12). Among them, the p30/32 cell surface antigen (also known as the MIC2 gene product), which can be detected by antibodies such as HBA71 and O13, and the reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 11 and 22 t (11;22)(q24;q12), which results in the formation of chimeric transcripts of EWS/FLI-1, are believed to be characteristic of this family of tumors (1). In this case the MIC-2 immunoreactivity and rearrangement of EWSR1 were observed. Because primary pulmonary ES/PNET is very rare, we tested several markers for small cell carcinomas such as CK, SCLC, chromogranin, CK7, CK19, and TTF-1, which were all negative. Ultimately, FISH revealed an EWSR1 22q12 rearrangement, which confirmed the diagnosis cytogenetically.

The most common CT finding of ES/PNET reported is a heterogeneously enhancing mass. Occasionally, a central, non-enhancing, low-density area is seen within the mass (12). In our case, well-enhanced linear opacity was observed inside the mass. In the FDG-PET scan, the SUV was 6.22, which is comparable with that in a previous study of Ewing sarcoma (SUV of 4.54±2.79). In the diagnosis of ES/PNET, a FDG PET scan is not diagnostic, but the sensitivity and specificity of the examination is quite high, 96% and 78%, respectively (13).

The treatment of ES/PNET is aggressive with the most effective treatment being a surgical resection with combination chemotherapy and high-dose radiation therapy. When resectable, the surgical excision must be wide in accordance with classic oncological principles (14, 15). A lobectomy including the mass lesion was performed and combination chemotherapy was subsequently administered.

In conclusion, we experienced a primary pulmonary ES/PNET. Although the primary pulmonary ES/PNET is an extremely rare soft tissue sarcoma, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a primary pulmonary mass.

References

- 1.Tsuji S, Hisaoka M, Morimitsu Y, Hashimoto H, Jimi A, Watanabe J, Eguchi H, Kaneko Y. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the lung: report of two cases. Histopathology. 1998;33:369–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imamura F, Funakoshi T, Nakamura S, Mano M, Kodama K, Horai T. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lung: report of two cases. Lung Cancer. 2000;27:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikami Y, Nakajima M, Hashimoto H, Irei I, Matsushima T, Kawabata S, Manabe T. Primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). A case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:113–119. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn AG, Avagnina A, Nazar J, Elsner B. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:397–399. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0397-PNTOTL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewing J. Classics in oncology. Diffuse endothelioma of bone. Proceedings of the New York Pathological Society, 1921. CA Cancer J Clin. 1972;22:95–98. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tefft M, Vawter GF, Mitus A. Paravertebral "round cell" tumors in children. Radiology. 1969;92:1501–1509. doi: 10.1148/92.7.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang MS, Yoon HK, Choi JB, Eum JW. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma of the hard palate. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:687–690. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.4.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charney DA, Charney JM, Ghali VS, Teplitz C. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the myocardium: a case report, review of the literature, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1365–1369. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danner DB, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Hayashi R, Griffin CA, Perlman EJ. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor arising in the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo HL, Jun SY, Choi G, Ro JY, Ahn H, Cho KJ. Primary Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the kidney: report of two cases. Korean J Pathol. 2003;37:145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie DR, Bilous AM, Carr PJ. Diagnostic difficulties in extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma: a proposal for diagnostic criteria. Australas Radiol. 1997;41:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1997.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin JH, Lee HK, Rhim SC, Cho KJ, Choi CG, Suh DC. Spinal epidural extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma: MR findings in two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:795–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyorke T, Zajic T, Lange A, Schafer O, Moser E, Mako E, Brink I. Impact of FDG PET for staging of Ewing sarcomas and primitive neuroectodermal tumours. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27:17–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000186608.12895.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Jurgens HF, Voute PA, Gadner H, Craft AW. Prognostic factors in Ewing's tumor of bone: analysis of 975 patients from the European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3108–3114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eroglu A, Kurkcuoglu IC, Karaoglanoglu N, Alper F, Gundogdu C. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma of the diaphragm presenting with hemothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:715–717. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]