Abstract

Aging is associated with a decline in skeletal muscle function. Previous research suggests that this decline in skeletal muscle function may, in part, be explained by an age-associated decline in the ability of skeletal muscle to reinnervate and/or age-associated changes in fiber types and distribution during reinnervation. This study used a nerve-repair graft model to investigate age-associated changes in the ability to reinnervate via expression of neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), a marker of denervated and recently reinnervated muscle fibers and changes in fiber type and Type I fiber grouping in medial gastrocnemius (MG) muscles of 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male Fischer 344 rats. Age had no effect on total MG muscle fiber number. Aging and nerve-repair grafting led to an increase in percent Type I and a decrease in percent Type IIB fibers. Aging and nerve-repair grafting led to an increase in NCAM positive fibers and an increase in the percentage of enclosed Type I muscle fibers, which was greatest in the 24 month nerve-repair grafted group. Thus, we conclude that diminished contractile function of aged and/or nerve-repair grafted MG muscle may be explained, in part, by an increase in the percentage of denervated fibers.

Keywords: Neural cell adhesion molecule, Denervation, Nerve-repair grafting, Muscle fiber type-grouping

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with a decline in the mechanical function of skeletal muscle (Eddinger et al., 1985; Florini and Ewton, 1989; Coggan et al., 1992). We have previously shown that age-associated deficits in specific force, normalized power and maximum sustainable power have been observed in medial gastrocnemius (MG) muscles of male Fischer 344 rats (Larkin et al., 1998). Previous research also suggests that this decline in function may be explained, in part, by a decline in the ability of aged muscle to reinnervate or alter patterns of fiber type expression following normal denervation–reinnervation processes that occur in skeletal muscle throughout the life-span of the animal. Therefore, this study sought to determine whether aging was associated with diminished ability of senescent muscle to reinnervate following nerve-repair grafting and whether the denervation–reinnervation process was associated with changes in fiber type proportion and Type I fiber distribution.

Nerve-repair grafting has been used to test the effects of denervation and reinnervation on muscle function. In previous studies, we have used a vascularized nerverepair graft procedure to investigate the reinnervation of senescent MG muscle without the possible confounding factors of an age-associated decrease in regeneration of myocytes following ischemia induced necrosis, a graft effect on muscle mass or an age-associated decrease in the regeneration of muscle tendon junctions (Larkin et al., 1998). The data from this previously published study demonstrated that there was full recovery of muscle mass and that nerve-repair grafting and aging was independently associated with diminished muscle contractile function. In addition, the deleterious effect of nerve-repair grafting on muscle function was significantly greater in old animals. Based on this previous study, we hypothesized that the diminished ability to recover skeletal muscle mechanical function following a nerve-repair procedure may be due, in part, to an impairment of muscle reinnervation and that this impaired reinnervation is exacerbated by advanced age.

Following denervation and during reinnervation, neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) protein is abundantly expressed in non-synaptic regions of denervated and reinnervating myofibers (Covault and Sanes, 1986). Reinnervation of denervated fibers leads to the disappearance of N-CAM from non-synaptic regions of (Covault and Sanes, 1986). Therefore, utilizing immunohistochemistry techniques, one can use NCAM antibodies to detect the population of myofibers in crosssections of muscle that would not respond to neural stimulation (Cashman et al., 1987). We have used this technique to monitor the reinnervation efficiency following denervation in 6-, 12- and 24-month-old animals and to determine the approximate mass to fibers that would contribute to mass but not force.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the process of reinnervation by Type I fibers is faster than by Type IIB fibers (Lowrie and Vrbova, 1984; Choi et al., 1996). In accordance, preferential reinnervation of Type I fibers following nerve-repair leads to an increase in type-grouping of Type I fibers in reinnervated muscle (Karpati and Engel, 1968; Albani et al., 1988; Yoshimura et al., 1999). Thus, if during the life span of the animal denervation–reinnervation is a normal ongoing physiological process, one would expect to see an increase in the type-grouping of Type I fibers. It is possible that fiber type-grouping may alter the ability of the muscle to smoothly and efficiently contract when stimulated, which may be an explanation for some of the age-associated changes in muscle function. However, to relate the changes in fiber type grouping to specific functional measures is difficult.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to test the hypotheses that senescent skeletal muscle will have: (1) an increased percentage of denervated muscle fibers; (2) an increased Type I fiber type-grouping similar to findings with nerve repair grafting; and (3) both the increased percentage of denervated fibers and fiber type-grouping will be more pronounced in nerve-repair grafts of senescent compared with young or adult rat muscles. To test these hypotheses we determined fiber type composition and distribution and the expression of NCAM positive muscles fibers in young-mature (6 month), middle-aged (12 month) and senescent (24 month) control and nerve-repair grafted MG muscles.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal model and animal care

Studies were carried out on male Fischer 344 rats obtained from the National Institute on Aging’s animal colony maintained by Harlan Sprague–Dawley Laboratory (Indianapolis, IN). All rats were acclimated to our colony conditions, i.e. light cycle and temperature, for 1 week prior to the nerve-repair grafting procedure. Rats were housed individually in hanging plastic cages (28 × 56 cm) and kept on a 12:12 light:dark light cycle at a temperature of 20–22 °C. The rats were fed Purina Rodent Chow 5001 laboratory chow and water ad libitum. All surgical procedures were performed in an aseptic environment with animals in a deep plane of anesthesia induced by intraperitoneal injections of sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg). Supplemental doses of pentobarbital were administered as required to maintain an adequate depth of anesthesia. All animal care and animal surgery were in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (UPHS, NIH Publication No. 85-23) and the experimental protocol was approved by the University Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

2.2. Medial gastrocnemius nerve-repair grafting procedure

Fifteen rats underwent a nerve-repair grafting procedure of the MG muscle at ages 2, 8 and 20 months (N = 5 from each age group). Use of either the right or left MG was randomly selected for the nerve-repair grafting procedure. The MG contralateral to the nerve-repair grafting procedure was used as a control. Both the nerve-repair grafted and contralateral MG from each animal were studied for fiber type and NCAM expression.

We chose to study the effect of nerve-repair grafting on metabolic and contractile function in MG muscle because it is large enough to provide adequate samples for metabolic function assays and it is an accessible muscle with a fiber type composition comparable to humans. The MG is innervated by only one nerve (a branch of the tibial nerve) which makes microsurgical denervation and repair and subsequent monitoring of contractile properties feasible.

Orthotopic, nerve-repair grafts of the MG muscle were performed as previously described (Larkin et al., 1998). Briefly, the left or right MG was isolated from surrounding muscle and connective tissue, the distal and proximal tendons were severed and the muscle was lifted, vasculature still intact, enough to verify complete separation from all other tissue. In this procedure, the MG was not lifted more than a few millimeters from its muscle bed. The muscle was then placed back into its original position and the tendons were repaired using 8-0 nylon suture. The branch of the tibial nerve innervating the MG was isolated, severed and then repaired using epineurial sutures of 11-0 nylon. Care was taken to leave the blood supply intact. The incision was closed in layers using 4-0 nylon suture. The animals were allowed to recover for 120 days, which is sufficient to allow stabilization of whole muscle maximal tetanic tension (Po) of nerve-repair muscle grafts (Guelinckx and Faulkner, 1992).

Following the 120 day recovery period, each animal was weighed, anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg) and the MG muscle was removed, weighed for determination of mass, quickly frozen in dry ice and isopentane, and stored at −20 °C until analyzed. Due to the time intense and tedious task of counting, classifying and determining the area of each individual fiber in the entire cross-section of muscle, we chose to limit the number of muscles analyzed to five per group. We do acknowledge however that due to the small sample size, we risk missing some true differences between groups. To decrease the experimental error introduced by fixation of muscle sections, we processed all muscles in both the myosin ATPase and NCAM analysis in batches of muscles with included representatives of all three age groups and both experimental groups.

2.3. Myosin ATPase fiber typing

A muscle biopsy specimen taken from the middle of the nerve-repair grafted MG and the control MG was used for fiber typing in five animals from each age and experimental group. Sections 10 µm thick were cut in a cryostat and incubated at varying pH conditions to measure myofibrillar ATPase activity. Muscle fibers were classified as Type I and Type II on the basis of myofibrillar ATPase activity at pH 9.4, as previously described by Brooke and Kaiser (1970). Type II fibers were further subdivided into Type IIA and IIB on the basis of myofibrillar ATPase activity at pH 4.6. The entire cross-sectional area (CSA) of each MG biopsy section was digitized, each fiber in the entire cross-section was counted, type classified and its area calculated using a computerized Bioquant Imaging System (R&M Biometrics, Inc., Nashville, TN).

The following parameters of fiber type distribution were calculated: average fiber CSA for each fiber type (the CSA of every fiber was determined morphometrically and then the average CSA for all fibers for a given fiber type was calculated), percentage of total fibers of each fiber type (the number of fibers of a given fiber type divided by the total number of fibers in the cross-section × 100) and the percentage of fiber type area (the total CSA of a fiber type divided by the total CSA of the muscle cross-section × 100). In order to determine the degree of fiber type grouping, the percentage of enclosed Type I fibers in cross-section was also determined (Lexell and Downham, 1991). A Type I fiber is considered enclosed if it is completely surrounded by other Type I fibers within the same muscle bundle.

2.4. Neural cell adhesion molecule expression

NCAM expression was determined from a biopsy obtained from the middle of the MG from both the nerve-repair grafted and control muscles in all five animals in each age and experimental group. A 10-µm thick section was sliced using a cryostat and mounted on a slide. Each section was incubated in 100% methanol for 10 min at −20 °C, followed by a 10 min rinse in PBS (product No. P3813; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) at room temperature. Next, the section was blocked with 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for 60 min at room temperature followed by incubation of a 1:20 dilution of rabbit antineural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) affinity purified polyclonal antibody (Chemicon International Inc., Te-mecula, CA) for 16 h at −4 °C. The accuracy of this primary antibody to bind to denervated fibers was tested by incubating with 7 day denervated and partially denervated muscle samples. Incubation with the primary antibody was followed with 3 × 10 min PBS rinses and incubation with Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) diluted 1:100 and FITC-labeled α-bungarotoxin (product No. T9641; Sigma) diluted 1:100 for 60 min at room temperature. α-Bungarotoxin was added to the incubation period with the secondary antibody because it binds to acetylcholine receptors in the postsynaptic membrane and is used to identify motor endplates. A muscle fiber was defined as denervated if it labeled positively for NCAM and negatively for α-bungarotoxin. Sections were then air dried, mounted with DPX mountant (Fluka Biochemica, Milwaukee, WI). The entire cross-sectional area of each MG section was then digitized, each NCAM positive fiber was identified and its area measured using a computerized Bioquant Imaging System (R&M Biometrics Inc.). NCAM positive fibers were identified in the MG biopsy section immediately consecutive to the section used for fiber typing, allowing the fiber type of each NCAM positive fiber to be identified. Individual cells that bound anti-NCAM antibody and did not bind α-bungarotoxin were classified as NCAM positive; the rest of the cells were classified as NCAM negative.

2.5. Statistics

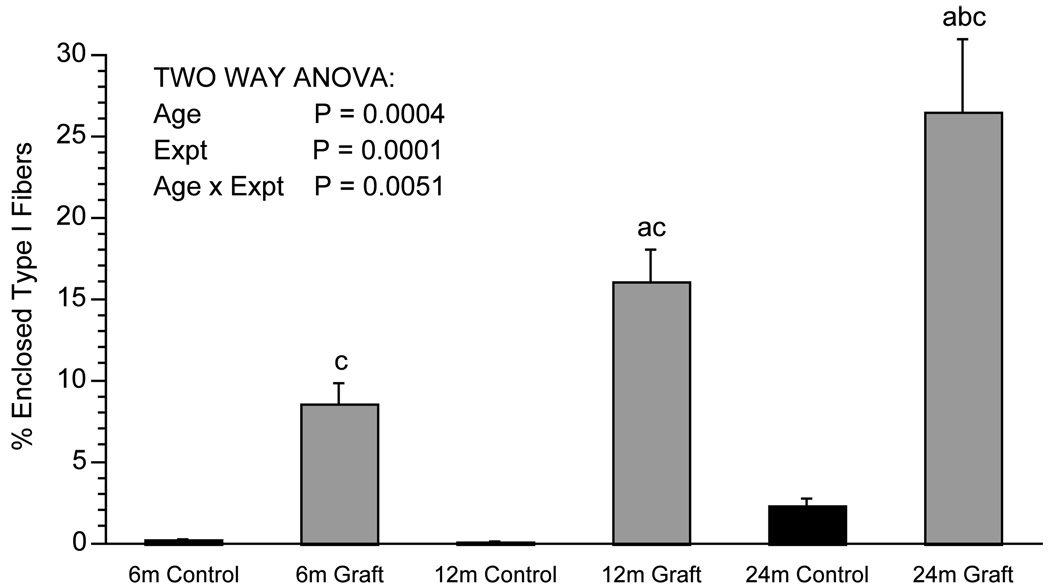

Values are presented as means ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed using Statview 4.01 (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences between rats at various age and nerve-repair grafted groups. When a significant main effect was found, the Fisher’s least-significant difference post hoc test was used to determine differences between the age and nerve-repair grafted groups. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. In all two-way ANOVA comparisons (except Fig. 4; the percentage of enclosed Type I fibers in cross-section) there was no significant interaction between age and nerve-repair grafted groups. Therefore, we are valid in analyzing all 30 subjects into one entire analysis, increasing our N for the entire experiment to 30 subjects and not just five per group. We recognize that this cannot be carried out for Fig. 4 and are more cautious to draw conclusions with respect to this data set.

Fig. 4.

The percentage of enclosed Type I fibers in cross-section in medial gastrocnemius muscle from 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male F344 rats. N = 5 per group. Values means ± S.E. Both age and nerve-repair grafting resulted in an increased percentage of enclosed Type I fibers. This graft effect was largest in the oldest age group. (a) Significantly different from 6 month group. (b) Significantly different from 12 month group. (c) Graft significantly different from control within same age group. Expt = experiment: graft versus control.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of nerve-repair grafting

There was no significant effect of nerve-repair grafting on MG muscle mass (Table 1). There was an increase in the total number of muscle fibers with nerve-repair grafted compared to age-matched controls (Table 1). However, this only reached statistical significance with a post-hoc test in the 6-month group. There was a decrease in the total cross-sectional area observed in nerve-repair grafted compared to control MG muscle, with statistical significance of a post-hoc test in the 12- and 24-month-old groups (Table 1). There was a graft effect on the total number and the percentage of NCAM positive fibers in MG muscle cross-section by ANOVA with significant increases in the 12- and 24-month-old nerve-repair grafted compared to control MG muscle (Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively). The average CSA of individual Type I and Type IIB muscle fibers decreased following the nerve-repair grafting procedure, while Type IIA fibers were unaffected by the surgical procedure (Table 1). Nerve-repair grafting led to a shift in distribution of fiber types: increased percentage of Type I fibers and decreased percentage of IIB fibers compared to control muscle (Fig. 2). Similarly, the percentage of the total CSA determined by Type I fibers increased, while the percentage of the total CSA type determined by IIB fibers decreased following nerve-repair grafting (Fig. 3). Nerve-repair grafting led to a significant increase in percentage of Type I fibers that are enclosed by other Type I fibers (Fig. 4). This type-grouping of Type I fibers in nerve-repair grafted muscle is illustrated in Fig. 5, which compares one 6-month control muscle (Fig. 5A) with one 6-month nerve-repair grafted (Fig. 5B) muscle. Instead of a heterogeneous population of fibers found in control muscle, there is clustering of Type I fibers following the nerve-repair grafting procedure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of grafted and control medial gastrocnemius muscle biopsies in 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male Fischer rats

| Control (6 months) |

Graft (6 months) |

Control (12 months) |

Graft (12 months) |

Control (24 months) |

Graft (24 months) |

Effect of graft (P value) |

Effect of age (P value) |

Age × graft (P value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||

| MG muscle mass (mg) | 716 ±14 | 720 ±23 | 781 ± 18a | 763 ± 22 | 673 ± 12b | 603 ± 44a,b,c | 0.13 | < 0.0001 | 0.26 |

| Total number of fibers | 6591 ± 395 | 8810 ± 713c | 6605 ± 836 | 7169 ± 1037 | 6010 ± 481 | 7381 ± 245 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.48 |

| Total muscle cross section area (mm2) | 21.9 ± 2.2 | 20.8 ± 1.3 | 26.7 ± 2.8 | 19.9 ± 1.3c | 20.4 ± 0.8b | 15.9 ± 1.3a | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| Total number of NCAM positive fibers | 154 ± 22 | 206 ± 44 | 120 ± 28 | 349 ± 82c | 243 ± 52 | 431 ± 72a,c | 0.0018 | 0.026 | 0.25 |

| Fiber cross section area (µM2) | |||||||||

| Type I | 2420 ± 360 | 1500 ± 70c | 2320 ± 210 | 1760 ± 180c | 2260 ± 230 | 1670 ± 140c | 0.0004 | 0.90 | 0.64 |

| Type IIA | 2600 ± 100 | 2130 ± 60 | 2830 ± 310 | 2550 ± 260 | 2380 ± 230 | 2440 ± 290 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.51 |

| Type IIB | 3350 ± 300 | 2550 ± 100 | 4130 ± 570 | 3120 ± 350c | 3030 ± 290b | 2430 ± 250 | 0.0059 | 0.028 | 0.82 |

Values are means ± S.E.

Significantly different from 6 month group.

Significantly different from 12 month group.

Graft significantly different from control within same age group.

Fig. 1.

The percentage of total muscle cells in cross-section in medial gastrocnemius muscle positive for neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) from 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male F344 rats. N = 5 per group. Values means ± S.E. Both age and nerve-repair grafting resulted in an increased percentage of NCAM positive muscle cells, particularly in the 24-month-old rats. (a) Significantly different from 6 month group. (b) Significantly different from 12 month group. (c) Graft significantly different from control within same age group. Expt = experiment: graft versus control.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of the total cross-sectional area of each fiber type in medial gastrocnemius muscle from 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male F344 rats. N = 5 per group. Values means ± S.E. Both age and nerve-repair grafting resulted in an increase in the percentage of muscle fibers represented by Type I and a decrease in the percentage of muscle fibers represented by Type IIB fibers, particularly in the 24-month-old rats. (a) Significantly different from 6 month group. (b) Significantly different from 12 month group. (c) Graft significantly different from control within same age group. Expt = experiment: graft versus control.

Fig. 3.

The percentage of total area in cross-section represented by Type I, Type IIA and Type IIB muscle fibers in cross-section in medial gastrocnemius muscle from 6-, 12- and 24-month-old male F344 rats. N = 5 per group. Values means ± S.E. Both age and nerve-repair grafting resulted in an increase in the percentage area represented by Type I and a decrease in the percentage area represented by Type IIB fibers, particularly in the 24-month-old rats. (a) Significantly different from 6 month group. (b) Significantly different from 12 month group. (c) Graft significantly different from control within same age group. Expt = experiment: graft versus control.

Fig. 5.

(A) A representative cross-section of muscle from a 6-month-old control medial gastrocnemius muscle. (B) A representative cross-section of muscle from a 6-month-old nerve-repair grafted medial gastrocnemius muscle. This figure illustrates the increased grouping of Type I fibers in nerve-repair grafted (B) compared to control (A) MG muscle. Type I fiber grouping is defined as an increase in percentage of Type I fibers that are enclosed by other Type I fibers.

3.2. Effect of aging

Muscle mass increased from 6 to 12 months and decreased from 12 to 24 months (Table 1). There was no significant effect of age on MG fiber number. Total muscle CSA significantly decreased with age (Table 1). There was a significant decline in total muscle CSA in the nerve-repair grafted MG from 6- to 24-month-old animals. In the control animals, the total muscle CSA increased in the 12 versus the 6 month and then decreased in the 24-month-old MGs. This may be due to the fact that the 6-month-old MG muscle has not reached full development. There was a significant increase in the total number and percentage of NCAM positive cells with age (Table 1). The total number and percentage of NCAM positive fibers in control muscles was significantly increased in the 24- compared with the 6-month and the percentage of NCAM positive cells were significantly increased in both 12- and 24-month nerve-repair grafted muscles compared with the 6-month nerve-repair grafted group (Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively). The CSA of individual muscle fibers increased in the Type IIB population from 6 to 12 months and then decreased in the 24-month-old animals with no significant difference in individual muscle fiber CSA between the 6 and 24 month muscles. There was no detectable age effect on fiber CSA for Type IIA fibers. There was a significant age-associated shift in distribution of fiber types: increase in the percentage of Type I and Type IIA and a decrease in the percentage of Type IIB in the 24- compared to the 6- and 12-month-old muscles (Fig. 2). Similarly, there was an age effect on fiber type total CSA: increased percentage of total CSA of Type I and decreased percentage of the total CSA of Type IIB in 24 month compared to 6 and 12 month muscle (Fig. 3). Aging led to a significant increase in percentage of Type I fibers that are enclosed by other Type I fibers (Fig. 4).

There was a significant interaction of age and nerve-repair grafting on Type I fiber grouping. The combination of aging and nerve-repair grafting led to greater Type I fiber grouping in the 24 month nerve-repair grafted compared to the 6- and 12-month-old nerve-repair grafted animals. There were no statistically significant interactions between age and nerve-repair grafting for any of the remaining parameters measured. However, the graft effect on both the number and percentage of each fiber type, as well as the percentage of NCAM positive fibers, tended to be greater in the 24-month-old animals compared to the younger groups. Given the small sample size used in this study, we cannot exclude an interaction between age and nerve-repair grafting on these measures.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates an increase in the percentage of NCAM positive muscle fibers in cross-sections of MG muscle of 24-month-old animals compared to young controls, indicating an age-related increase in the percentage of denervated and recently reinnervated (non-innervated) fibers in senescent MG muscle. This study extends the findings of Andersson et al. (1993), which showed that both NCAM protein and mRNA content of total muscle homogenates were increased in hindlimb skeletal muscle of 24-month-old compared to 9-month-old Wistar rats. We also observed an increase in the expression of NCAM positive fibers following nerve-repair grafting, with the largest increase in the percentage of NCAM positive cells in the 24-month-old nerve-repair grafted group. This increase in the population of non-innervated muscle fibers could, in part, contribute to the decline in contractile function observed in nerve-repair grafted and aging muscle (Larkin et al., 1998). In fact, data from a collaborating laboratory indicates that in 27–29-month-old male Fisher 344 rats, ≈ 15% of the observed deficit in specific force can be explained by the presence of non-innervated muscle fibers (Urbanchek et al., 2001).

In addition, the present study also demonstrates graft-and age-associated increases in fiber-grouping of Type I fiber populations. Type-grouping of Type I fiber populations in reinnervated fibers has been observed previously (Albani et al., 1988; Yoshimura et al., 1999). The present study extends these findings to aging muscle and demonstrates that following nerve-repair grafting, type-grouping of Type I fibers is greatest in the 24 month MG muscle compared to the younger animals. The effect of this reorganization of fibers on the firing patterns of motor neurons and the recruitment of muscle fibers during contraction has not been studied. It is possible that shifts in fiber grouping may alter the ability of the muscle to smoothly and efficiently contract when stimulated, to relate the changes in fiber type grouping to specific functional measures is difficult.

Many studies have investigated age-related changes in muscle fiber type populations as an explanation for age-associated declines in muscle function. Several investigators have observed no age-associated changes in fiber type populations (Eddinger et al., 1985; Florini and Ewton, 1989; Coggan et al., 1992), while others have shown an increase in Type I and a decrease in Type IIB fibers with advancing age (Ansved and Larsson, 1989; Sugiura et al., 1992). In the rat, using SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, it has been shown that there are four myosin heavy chain isoforms I, IIA, IIX and IIB expressed in the hindlimbs of the rat (Larsson et al., 1999). In aging Wistar rats, Sugiura et al. (1992) has shown that there is an increase in the population of IIX and a decrease in the population of IIB without any age-related change in IIA or I fiber populations. In the present study, using myosin ATPase staining, the MG muscle of male Fisher 344 rats showed an increase in both the number of Type I fibers and percentage area of Type I and Type IIA fibers and a decrease in both the number and percentage area of Type IIB fibers in the senescent compared to young controls. Since sustained power is developed predominately in Type IIA and Type I fibers (Brooks and Faulkner, 1991), which both increased with age and grafting, the diminished sustained power in the aged and nerve-repair grafted MG cannot be explained by shifts in fiber types. However, with myosin ATPase staining it is not possible to distinguish between Type IIB and IIX. Therefore, it is possible that there is an even greater decrease in Type IIB due to an age-associated shift to IIX and an overall decrease in the combined proportion of IIB/IIX fibers. Furthermore, the finding of a similar shift in the IIB/IIA populations following the nerve-repair grafting procedure supports the idea that aging is associated with a denervation/reinnervation process affecting skeletal muscle.

We also observed an increase in muscle fiber number following the nerve-repair grafting procedure. In accordance with this study, two additional studies also observed an increase in fiber number following muscle damage and repair (Vaugan, 1992; Gill and Shakoori, 1998). Kelly (1996) reviewed all experimental designs which implemented mechanical overload during the muscle repair process and found consistent increases in muscle mass, muscle fiber area (hypertrophy) and muscle fiber number (hyperplasia). Kelly also reported that following mechanical overload due to stretch of the muscle, the greatest increase in hyperplasia was observed. In our nerve-repair grafting procedure, the tendons were severed and muscle orthotopically sutured back on to the remaining tendon stumps. This tendon repair procedure produces mechanical stretch overload on the muscle. Therefore, mechanical stress overload may possibly explain the increase in fiber number observed in this study. Even though we observed an increase in fiber number in every nerve-repair grafted muscle compared to its control, we also realize that the observed hyperplasia may be due to a graft induced architectural change in the muscle. It may be that following the nerve-repair grafting procedure, the angle of pennation of the MG increases, leading to an increase in the number of fibers appearing in any one cross-sectional slice, which would explain an overestimation of fiber number.

In conclusion, this study illustrates that there is an age- and graft-associated increase in NCAM positive fibers in MG muscle of Fischer 344 rats. These findings indicate that there is an increase in the population of non-innervated fibers, following nerve-repair grafting and with advanced age in this animal model. The percentage of NCAM positive fibers was greatest in the oldest nerve-repair grafted muscles suggesting that incomplete muscle fiber reinnervation is more pronounced in nerve-repair grafts of old compared with young or adult, rat muscles. In addition, we found an increased type-grouping of Type I muscle fibers in both nerve-repair grafted and senescent MG muscle, which may also contribute to their diminished function. The similarity of findings following nerve-repair grafting and with aging supports the hypothesis that denervation and/or diminished reinnervation may be an important factor in aging effects on muscle. Due to the small sample size and the limited samples of biopsied muscles examined, we cannot exclude an interaction between age and nerve repair grafting on Type I fiber grouping and percentage of NCAM positive fibers. Further studies need to be carried out to assess the relationship between fiber type-grouping and change in muscle function.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alyssa Cary, Cheryl Hassett and Geoff Rezvani for their technical assistance. This research was supported in part by an NIA training grant (T32 AG00114), NIH grants (K01-AG00710 and AG10821), the Core Facility for Aged Rodents of the Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at the University of Michigan (NIH grant AG08808) and by the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

References

- Albani M, Lowrie MB, Vrbova G. Reorganization of motor units in reinnervated muscles of the rat. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988;88:195–206. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson AM, Olsen M, Zhernosekov D, Gaardsvoll H, Krog L, Linnemann D, Bock E. Age-related changes in expression of the neural cell adhesion molecule in skeletal muscle: a comparative study of newborn, adult and aged rats. Biochem. J. 1993;290:641–648. doi: 10.1042/bj2900641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansved T, Larsson L. The effects of age on contractile, morphometrical and enzyme-histochemical properties of the rat soleus muscle. J. Neurol. Sci. 1989;93:105–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke MH, Kaiser KK. Muscle fiber types: how many and what kind? Arch. Neurol. 1970;23:369–379. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480280083010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Forces and powers of slow and fast skeletal muscles in mice during repeated contractions. J. Physiol. 1991;436:701–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman NR, Covault J, Wollman RL, Sanes JR. Neural cell adhesion molecule in normal, denervated, and myopathic human muscle. Ann. Neurol. 1987;21:481–489. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Harii K, Asato H, Ueda K. Aging effects in skeletal muscle recovery after reinnervation. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Hand Surg. 1996;30:89–98. doi: 10.3109/02844319609056389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan AR, Spina RJ, King DK, Rogers MA, Brown M, Nemeth PM, Holoszy JO. Histochemical and enzymatic comparison of the gastrocnemius muscle of young and elderly men and women. J. Gerontol. 1992;47:B71–B76. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.3.b71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covault J, Sanes JR. Distribution of N-CAM in synaptic and extrasynaptic portions of developing and adult skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1986;102:176–730. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.3.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddinger TJ, Moss RL, Cassens RG. Fiber number and type composition in extensor digitorum longus, soleus, and diaphragm muscles with aging in Fisher 344 rats. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1985;33:1033–1041. doi: 10.1177/33.10.2931475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florini JR, Ewton DZ. Skeletal muscle fiber types and myosin ATPase activity do not change with age or growth hormone administration. J. Gerontol. 1989;44:B110–B117. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.5.b110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill N, Shakoori AR. Effect of tenotomy on extensor digitorum longus muscle in Sprague Dawley rats. Folia Biol. 1998;46:109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelinckx PJ, Faulkner JA. Parallel-fibered muscles transplanted with neurovascular repair into bipennate muscle sites in rabbits. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1992;89:290–298. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199202000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpati G, Engel WK. Histochemical investigation of fiber type ratios with the myofibrillar ATP-ase reaction in normal and denervated skeletal muscles of guinea pig. Am. J. Anat. 1968;122:145–155. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001220109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly G. Mechanical overload and skeletal muscle fiber hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;81:1584–1588. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin LM, Kuzon WM, Supiano MA, Galecki A, Halter JB. Effect of age and neurovascular grafting on the mechanical function of medial gastrocnemius muscles of Fischer 344 rats. J. Gerontol. 1998;53A:B252–B258. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.b252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Hook P, Pircher P. Regulation of human muscle contraction at the cellular and molecular levels. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999;20:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s100720050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexell J, Downham DY. The occurrence of fibre-type grouping in healthy human muscle: a quantitative study of cross-sections of whole vastus lateralis from men between 15 and 83 years. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;81:377–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00293457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie MB, Vrbova G. Different pattern of recovery of fast and slow muscles following nerve injury in the rat. J. Physiol. 1984;349:397–410. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Matoba H, Miyata H, Kawai Y, Murakami N. Myosin heavy chain isoform transition in ageing fast and slow muscles of the rat. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1992;144:419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanchek MG, Picken EB, Kalliainen LK, Kuzon WM., Jr Specific force deficit in skeletal muscles of old rats is partially explained by the existence of denervated muscle fibers. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001;56:B191–B197. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.5.b191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaugan DW. Effects of advancing age in peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;323:219–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K, Asato H, Cederna PS, Urbanchek MG, Kuzon WM. The effect of reinnervation on force production and power output in skeletal muscle. J. Surg. Res. 1999;81:201–208. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]