Abstract

A qualitative study was done to explore attitudes and beliefs of African Americans regarding hypertension-preventive self-care behaviors. Five focus groups, with 34 participants, were held using interview questions loosely based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Analysis revealed themes broadly consistent with the TPB, and also identified an overarching theme labeled “circle of culture.” The circle is a metaphor for ties that bind individuals within the larger African American community, and provides boundaries for culturally acceptable behaviors. Three sub-themes were identified: one describes how health behaviors are “passed from generation to generation,” another reflects a sense of being “accountable” to others within the culture; and the third reflects negative views taken toward people who are “acting different,” moving outside the circle of culture. Findings provide an expanded perspective of the TPB by demonstrating the influence of culture and collective identify on attitude formation and health-related behaviors among African Americans.

Keywords: African American, Culture, Collective Identity, Hypertension, Self-care, Theory of Planned Behavior

African American Culture and Hypertension Prevention

Hypertension (HTN) is a common, progressive health problem contributing to significant morbidity and mortality among African Americans. Many precursors of HTN are preventable through lifestyle management, yet African Americans have a low prevalence of engaging in HTN-prevention self-care behaviors. Little is known about the attitudes and beliefs of African Americans related to HTN-prevention. Knowledge of those attitudes and beliefs may assist health care professionals to provide more effective interventions to reduce the disparity in HTN.

Hypertension Prevention among African Americans

One in three (33.5%) African Americans are hypertensive, which is the highest prevalence of any ethnic group surveyed. Additionally, 72% of African Americans with HTN do not have their BP controlled to within normal limits (Hajjar & Kotchen, 2003). To date, there is no evidence of a unique genetic variant related to the excess of HTN in Blacks; supporting the contention that race is a social, rather than biological concept (Daniel & Rotimi, 2003). Instead of genetic factors, lifestyle and socio-environmental factors are crucial to understanding HTN in Blacks (Cooper et al., 1997). There is sufficient empirical evidence to support five areas of lifestyle modification to decrease the risk of developing HTN. These include weight control, increased physical activity, limited alcohol intake, no tobacco use, and reduced dietary saturated fat and sodium (Campbell et al., 1999; Whelton et al., 2002). African Americans have difficulty in achieving these lifestyle modifications. The prevalence of Obesity (Class 2 and 3) among all ethnic groups is highest for African Americans of both genders (Must et al., 1999). Compounding the weight issue is the fact that 43% of African American women, and 26% of African American men are physically inactive (Crespo, Smith, Andersen, Carter-Pokras, & Ainsworth, 2000). Cardiovascular mortality increases in African Americans when the average consumption of alcohol is greater than one drink a day (Sempos, Rehm, Wu, Crespo, & Trevisan, 2003), yet binge drinking (more than five alcoholic drinks at one sitting) occurs in 14.5% of African Americans, and 4.5% are considered to be heavy drinkers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004). Smoking causes a significant rise in BP and contributes to increased cardiovascular mortality. Twenty-two percent of African Americans continue to smoke (Centers for Disease Control, 2004). Habitual ingestion of high levels of dietary salt (NaCl) is associated with increased blood pressures (Cooper et al., 1997; Stamler, 1997). Although not unique to any one racial/ethnic group, increased BP sensitivity to salt ingestion continues to be postulated as a key factor in African American HTN (Peters & Flack, 2001).

Theoretical Approaches to Understanding HTN Prevention Strategies

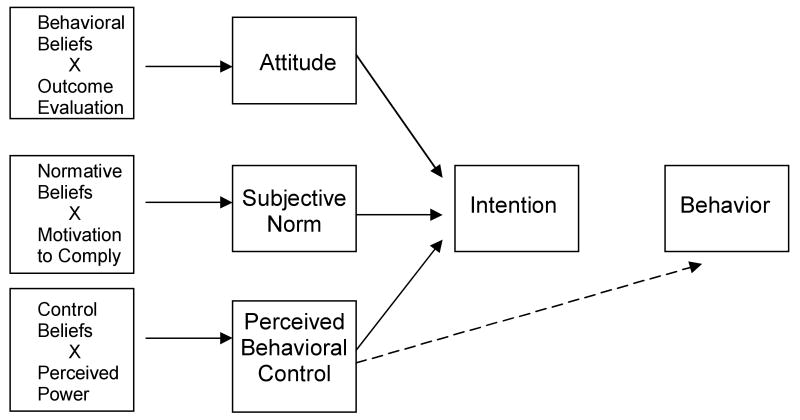

The Theory of Planned Behavior (Azjen, 1991, 2001) has been used in numerous studies to explain and predict human behavior. The TPB hypothesizes that attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control predict intention; and intention along with perceived behavioral control predicts actual health behaviors. In order to explain, and not just predict behavior, the TPB also examines important antecedent beliefs for each of these key concepts. Attitude toward a behavior is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct reflecting cognitive, conative, and affective beliefs regarding the behavior (Ajzen, 1988). These antecedent behavioral beliefs and the values held toward the expected outcomes of a given behavior form the informational foundation of attitude (Ajzen, 1991). Subjective norm is a person's perception of the social expectations to adopt a particular behavior. Antecedents to subjective norms include normative beliefs and motivation to comply. Normative beliefs are concerned with the likelihood that important others would approve or disapprove of a particular behavior, and motivation to comply is an assessment of how important it is for the person to have approval of important others (Ajzen, 1991). Perceived behavioral control reflects a person's beliefs as to how easy/difficult it will be to perform the behavior. Antecedents to perceived behavioral control include control beliefs and perceived power. Control beliefs reflect a balance between the factors that facilitate and barriers that impede engaging in a particular behavior.

The TPB has been used extensively in health behavior research. A number of reviews have reported its efficiency in predicting behaviors relevant to BP control such as diet, physical activity, and smoking, but most of this research has been done with non-Hispanic Whites (Ajzen & Timko, 1986; Godin & Kok, 1996; Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & Biddle, 2002). Studies specific to African Americans have found the theory to be effective in explaining and predicting cancer and sexual disease preventive behaviors (Bowie, Curbow, LaVeist, Fitzgerald, & Zabora, 2003; Bryan, Ruiz, & O'Neill, 2003; Jennings-Dozier, 1999; Jemmott, Jemmott, & Hacker, 1992), but with little research done regarding hypertension-preventive behaviors. The TBP has been used to examine smoking and exercise in African American children and undergraduate college students (Blanchard et al., 2003; Hanson, 1999; Trost et al., 2002), but not in adults. Regardless of the theoretical perspective used, no studies could be found that examined the totality of behaviors necessary to prevent HTN in African Americans. The TPB can assist in addressing this gap in knowledge by providing a framework to elicit attitudes and beliefs held by African Americans that influence their participation in hypertension-prevention behaviors.

Purpose

The purpose of the current study was to use the TPB as a guide to explore the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs of African Americans relative to initiating and maintaining self-care behaviors necessary to control blood pressure and prevent hypertension. This is the first phase of a larger study designed to develop a clinical tool that may assist health professionals design more effective interventions to reduce the disparity in HTN prevalence and sequelae. Instrument development based on the TPB requires that formative research be done to identify the salient, accessible beliefs commonly held by members of the population of interest (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Additionally, given the paucity of information specific to African Americans, use of a qualitative design allows an emic perspective to emerge. Such a perspective is important for developing a culturally relevant instrument (Tran & Aroian, 1999).

Design

A qualitative study using focus group methodology was conducted to obtain information regarding African American attitudes and beliefs regarding HTN preventive behavior. Human Investigation Committee approval was obtained prior to implementing the study.

Sample

Purposive sampling was used to recruit community-dwelling, healthy African-American adults between 25 to 60 years of age. Given noted differences in health promotion and health seeking behaviors, purposive sampling was done to obtain participants with varied educational and economic backgrounds. A segmentation strategy also was used to divide the composition of the groups by gender. These strategies were used to ensure that potentially distinct perspectives were obtained (Morgan & Scannell, 1998). A total of five focus groups were conducted. Three women's and two men's groups were held with a total of 34 participants ranging in age from 27 to 60 years. Participants represented a wide range of age, education, income, and levels of participation in preventive self-care behaviors.

Methods

Focus Group Format

Focus groups were used to obtain information regarding participants' experiences and beliefs related to HTN prevention, and to capitalize on the interaction that occurs within the groups to elicit a rich, detailed perspective. Five groups were conducted using a semi-structured interview format with three sets of questions loosely based on the TPB. The first set of questions addressed salient behavioral beliefs regarding HTN prevention behaviors. The second set of questions focused on normative beliefs and was designed to gain an understanding of the influence of family and friends on HTN preventive self-care behaviors. The third set of questions addressed control beliefs including perception of benefits and barriers to engaging in HTN prevention strategies.

Data Collection

The research team consisted of the primary investigator (PI), a group moderator, a data collector, and a doctorally prepared nurse who is an expert in qualitative methods. Six hours of training, including reviewing the interview guide, practicing interview techniques, and piloting the interview questions with representative participants, was done prior to data collection.

A moderator and a data collector were involved in each focus group session. The moderator lead the group discussion and kept participants focused on the research questions while the data collector acted as an observer and took field notes of each session. Initially, both the moderator and data collector were African American, which was done to increase the participants' level of comfort to self-disclose (Krueger, 1998). After each of the first two sessions, participants were asked if they would have disclosed the same information if a White researcher had been present and the answer was a strong affirmative. This became important when the original moderator became ill and the PI, who was White, had to moderate the remaining three focus groups. After moderating each of those sessions the PI would leave the room and the African American data collector would ask participants if they had any additional information they wanted to share among themselves. No other information was expressed.

The focus groups were held in locally convenient public places with private meeting facilities, such as churches and schools. Food, coffee and healthy snacks, were offered prior to the start of the focus groups. This short time period was used to “break the ice,” and to allow all members to arrive and get settled. The actual group sessions lasted about 90 minutes. This included time to obtain informed consent at the beginning of the session, to collect demographic data and distribute gift certificates as a “thank you” to participants at the end of the session, and also allowed sufficient opportunity for all participants to respond to the questions. All focus group sessions were audiotaped to ensure data accuracy.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data collection and analysis are inseparable processes, with the first step of analysis beginning during each group session. At the end of each focus group, the moderator provided a brief summary of key points that emerged from the discussions, and asked participants if this summary reflected their perception of what occurred. Field notes, recorded during each session, were used to record the context and impressions at the time. All group sessions were audiotaped and professionally transcribed. To ensure data accuracy, the PI reviewed and corrected the transcripts while listening to the audiotapes. The transcribed data were imported into the NVivo (v. 2.0; QSR, 2002) software program to facilitate further analysis.

Data from this study were analyzed using two different methods. First the data were analyzed using a loosely constructed a priori coding scheme based on the TPB, with codes related to behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. Coding in this manner follows the steps involved in instrument development as detailed by Azjen and Fishbein (1980), and was done with the next phase of the larger study in mind. Given that few studies have been done specifically with African Americans, open coding analysis also was conducted. The qualitative expert, who had not participated in any of the focus groups and was not familiar with TPB, used open coding to ensure that the data were not “forced” to conform to the preconceived theory coding, and to allow the possibility that additional or alternative themes might be identified in the data. Independent coding schemes were developed using each method of analysis and then identified themes were shared and discussed by team members. Discussions focused on whether the open coding themes could be interpreted within the broad theory concepts, and whether the theory coding captured the full range of ideas expressed by the participants. The PI created logical arguments for why the data fit the theory, while the person who had done open coding furthered the analytical process by challenging why it did not fit. Discussions and analysis continued until agreement of themes was reached and the investigators were satisfied that the categorization and overall schema presented was the best fit for the data.

Trustworthiness of Findings

Procedures for meeting the four criteria for trustworthiness of data and findings were used (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Credibility was addressed by running focus groups until data saturation occurred. Peer debriefing was done to identify investigator biases that could influence the final conclusions. Dependability was established by using a wide range of participants, delineating the team members' role in the project, using the same data collection protocol with each focus group, and by the co-investigators reviewing and critiquing each other's analysis and interpretation of the data (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Confirmability was established by an audit trail that included field notes, raw data in audiotapes, written transcripts, and detailed record of evolving coding schemes maintained within NVivo. Transferability was partially established by conducting external checks of the findings. Three African Americans not involved in the focus groups verified that the identified themes reflected their life experiences.

Findings

A review of the themes revealed some overlap between findings from the a priori theory coding and the open coding analysis. Although the a priori coding revealed themes consistent with the major TPB concepts of attitude, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norm, much of the data in each of these areas were not unique to African Americans and did not reflect the richness of what was said by the participants. A fuller perspective was obtained from the open coding and resulted in an additional, essential theme of a “circle of culture” being identified. The circle of culture is an overarching theme that provides a cultural and contextual perspective for understanding each of the TBP concepts within an African American sample.

Circle of Culture

The circle of culture is a metaphor representing the boundaries that enfold individuals within the traditions of the larger group, including traditions affecting hypertensive-preventive behaviors. The circle symbolizes ties that bind individuals within the African American community, and provides boundaries for culturally acceptable behaviors. The circle also represents boundaries that separate “insiders” from “outsiders,” based on the degree to which they embrace their cultural heritage. Besides arising from thematic analysis, the insider/outsider perspective also became apparent with linguistic analysis. Listening to the audiotapes revealed in-group tonal shifts including a change in grammar use and voice-tone patterns to a more vernacular form when shared traditions (e.g., food choices) were being discussed (Smitherman, 1975). These culturally shared norms put boundaries around the insiders, and reinforced their sense of connection with the larger African American community. Within the circle of culture, three important sub-themes were identified: “passed from generation to generation;” “accountable” to others within the culture; and “acting different.” Each of these themes will be discussed as they relate to concepts within the TPB.

Attitude

There are three component beliefs that form attitude: cognitive beliefs regarding causes and consequences of HTN; affective beliefs regarding the positive and negative feelings about engaging in HTN-preventive behaviors; and conative beliefs regarding commitment to actually performing those preventive behaviors (Ajzen, 1988). Evaluation of cognitive beliefs indicated that diet (i.e., food choices) was the most commonly discussed cause of HTN followed by “family patterns of poor eating habits” and “stressful lives.” One or two people in each group mentioned obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking as possible causes of HTN, but none of these topics generated much discussion in any of the groups, and no connection was made between diet and obesity. Men introduced alcohol as a cause, but this received little attention in the women's groups. All groups verbalized that serious, negative consequences such as stroke, cardiac problems, kidney disease, and premature death would result if BP was not controlled. Participants in all groups held strong, positive beliefs that self-care measures can prevent and control HTN resulting in people feeling better and living longer, healthier lives. Beliefs regarding strategies to prevent HTN focused on changing dietary patterns and reducing stress. Although common to all groups, the descriptions of “stressful lives” differed by socioeconomic status (SES). In the higher SES groups, two participants described the role of stress in this way:

…[Stress] is normal for the life we live. We're stressed, we say everything really fast, we don't rest, we're just bombarded, and we don't take care of ourselves, it's how we live.

…We live in a fast paced society, so people will quickly drive by fast food places on their way to the next thing, everything is so rush, rush…we don't take time for ourselves.

Participants with lower SES reported more stress based on exigencies of daily living. Lack of resources was a major source of stress that they believe affected blood pressure.

…People go untreated, they know that they have it [high BP] and don't have the resources to get the medication or whatever they need, and they already stressed out because of lack of [money] so it just adds to the problem they already have.

…We gotta learn how to deal with the stress that is causing it [high BP]…learn how to handle the problems and situations, instead of always worrying about what's always gonna be there, like bills and taxes ‘cause bills don't go away.

One father poignantly described the stress that comes from living in a poor, crime-ridden area:

…I would have to say worry [is major cause of HTN], because I have three girls, and there's really a lot of bad things in the world today with these school kids getting raped and stuff and I hope that when I let my daughters go to school that nothin' happen to them…if I got high BP it would come from worrying…I would worry about them a lot.

Passed from generation to generation

Although participants had the cognitive awareness of behaviors necessary to prevent HTN, and held positive beliefs that prevention was important, their commitment to engaging in those behaviors was strongly influenced by the circle of culture. The sub-theme of “passed from generation to generation” emerged as a powerful factor in attitude formation. Participants in each group expressed the belief that African American attitudes regarding health behaviors are strongly influenced by a collectively shared history that is “passed from generation to generation.” The two health-related areas most affected by this intergenerational connection are diet and trust in physicians.

There was a great deal of consensus that dietary choices and patterns of “poor eating” were “a problem in our culture”. Dietary habits were seen as being passed down through generations of African Americans. This theme is summarized in one participant's statement:

…We've been doin' it for so long, passed on from generation to generation to generation. We ain't taught to eat no baked fish, no salads, or nothin' like that. We brought up on pig's meat, greens, pork chops all that type stuff. …so it's behavior, it's what we taught, what we know, generation to generation to generation passed down, that's my point…

A lack of trust in physicians and a reluctance to seek medical care are additional habits passed down in the community, and were pervasive across all groups. Distrust of the health care system was based on personal and family experiences, as well as on care given to African Americans in general. The Tuskegee experiment, where black men were denied treatment for syphilis so doctors could study the disease's progression (Jones, 1993), was discussed in all groups.

…I'll never forget Tuskegee! I've read about it and I'll never forget it. I think sometimes being an African American and knowing history like I do, there's some distrust [in physicians]…

…A lot of people don't like taking medicine, some people when they finally go to the doctor, don't trust the doctor anyway. Then there is so many tricks and tests and studies done on people. For example, the people that have the syphilis [referring to Tuskegee] and they remember things like that and it makes it hard for them to trust…

Although participants attributed greater distrust of physicians to older African Americans, this distrust was reported as having considerable influence on the health behaviors of their children and grandchildren. One woman expressed it in this way:

…I think, too, with the older people since they don't like to go to the doctor, it kind of instill superstition in the younger people. All of them [older folks] not wanting to go to the doctor because of how they've been done along the lines, they pass that along. I think that might be some of the reasons why they [younger folks] don't go.

The lack of trust in physicians also was discussed specifically in relation to attitudes about BP control. One participant raised the question: “Why would doctors want to keep [people] healthy? They wouldn't have a job then as far as high blood pressure goes.” Participants then gave examples of patients being seen by so many different doctors and getting conflicting BP readings that it made them question their hypertensive diagnosis. Participants also expressed suspicions about physicians' motives for prescribing antihypertensive medications. As a result, participants described how many African Americans treat their BP based on the symptoms they felt, rather than following the prescribed medical regimen.

Perceived Behavioral Control

Although participants were knowledgeable about self-care strategies necessary to prevent HTN, discussion of control beliefs revealed few facilitators and focused more on barriers to engaging in those preventive behaviors. Barriers arising from within the individual were expressed in themes such as “change is hard,” “habits are hard to break,” and “stressful lives” make it difficult to do preventive self-care. External barriers also were identified including commercials that encouraged poor eating habits, lack of free exercise facilities, cost of eating healthy foods, and lack of information about HTN prevention in the community. Differences based on socioeconomic status were noted in the discussion of control beliefs. Participants having lower economic status were more likely to focus on external barriers and stated a need for greater educational and health care resources in the community to make changes in their lives. Participants with upper socioeconomic status were more likely to express the belief that individuals need to motivate themselves to change their behavior. These participants believed that there are sufficient resources available in the community, but it was up to the individual to access and use those resources to improve their health. Economic differences also were noted when the role of God was discussed. The beliefs of persons with higher SES were summarized by one participant who stated: “God entrusted this body to us and if we abuse it then we suffer repercussions for the way we treat it.” These participants saw prayer as a way to gain strength to make change and live a healthy lifestyle. This contrasts with a more fatalistic perspective espoused by participants with lower SES, as stated by one participant: “its all in God's hands.”

Accountable to each other

Within the circle of culture, the sub-theme of “accountable to each other” provides an expanded perspective for thinking about facilitators of behavioral change. In each of the focus groups a sense of collectivism was expressed. Participants described the belief that African Americans have a responsibility to be their “brother's keepers” and to be accountable for helping others within their culture live more healthfully. Here are exemplars:

…We are brothers and sisters and we have a sign up at home that says ‘It takes a village’ Sometimes it takes you being accountable to each other to help each other change our habits.

…‘I am my brother's keeper’. If that is true, if I know a person that's in crisis, that have some kind of debilitating illness, and I know that they don't do right, I have to be that person that is going to help that other person and maybe they will help another person. Take it upon yourself to pass it on like that…

Participants also expressed the need to be accountable for the sake of the children. They identified that there's a crisis of obesity among the children “because of bad habits of their parents.” Participants talked about the need for each adult to set an example for the children to follow. As one person stated: “you become a living testimony to those children that observe you…and they begin to ask questions and emulate you”.

Subjective Norm

Questions regarding normative beliefs and the influence of subjective norms on hypertension preventive behaviors stimulated the most discussion in all of the focus groups. Normative beliefs focus on behavioral expectations of “important referents.” In the literature, these important referents are often described as persons immediate to the individual (e.g., spouse, family, friends), but this does not capture the richness of the data expressed by participants in the current study. While gender and socioeconomic differences were noted in the discussions about attitude and perceived behavioral control, no such differences were noted in discussions of subjective norms. Participants in all groups, regardless of gender or socioeconomic status, discussed being part of an African American “culture.” They expressed a connection born out of a collectively shared history that went beyond their immediate social network, and bonded them with the larger social group. One participant captured this connectedness to the larger culture when he stated: “We basically are cousins; we come from the same family, you know.” The circle of culture theme encompasses and expands the TPB concept of subjective norm by drawing attention to the influence of this larger social group on health behaviors of African Americans.

One powerful example of the influence of culture on health behaviors was given by a group of women who described a recent church-sponsored event. The event was specifically designed to raise heart health awareness among church members. Following the two-mile walk, members participated in the concluding celebration that included a meal of fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, biscuits, and greens with ham. Thus the diet is so embedded in cultural norms that even when trying to promote health, traditional rather than healthy foods are served. This example illustrates that for African Americans many health behaviors are influenced by their larger culture. Unfortunately, that influence is often negative. Participants in all groups consistently described “social pressures” as the biggest deterrent stopping African Americans from engaging in those behaviors believed to control BP. Many participants described negative consequences if they tried to break cultural traditions and engage in preventive behaviors recommended by health care providers.

Acting different

Data within the circle of culture sub theme of “acting different” captured an insider versus outsider way of looking at the world. Participants described the efforts of others to keep the individual within the circle, to not change the habits that have been passed from generation to generation. Many women described a lack of support as they tried to serve their family what professionals would call “healthy” foods. The lack of support included being called a “diet Nazi”, being told they were “mean,” and having family members refuse to come to their house for a party because “they don't like the way I eat, or if they come, they bring their own food.” Participants described similar negative experiences of being seen as “acting different” by their family and friends when they changed behaviors other than their diets.

…I made a decision for my health reasons [to stop drinking]…and people look at me totally different. Totally! With family it's a good different, for real, but with others, it's not good.

…Outside the family it's like ‘Who the heck is she? She gone all high and mighty? What's she gonna go change her lifestyle?’

…I used to weigh 400 pounds and they don't like me now [that I've lost weight]. They think she thinks ‘She's this and that’, and it goes on in my family, I have nothing but myself, really, they're going to think that anyway…

“Acting different” separated them from the group, moving them toward the outside of the circle of culture. The ultimate exclusion from the circle occurred when participants were considered to be “acting white.” One participant described it this way:

…If you start taking care of yourself and start doing something that's against the norm people look at you funny, and you're ostracized. They say ‘You start to be Caucasian’…you're acting ‘white’ - you're acting ‘white!’

“Acting white” was seen as an insult, a derogatory label to be avoided. Fear of being seen as “acting white” was considered “prevalent to the point where it affects the choices that people make everyday, it's pervasive through every aspect of our lives.” Participants described this as a “huge” problem for African Americans, affecting everything that was being said about preventive self-care, and “holding them back on so many levels,” including health. Participants believed that many African Americans, to avoid being ostracized, will “stay on the level of their peers,” including engaging in behaviors they know are unhealthy — “even to the point of dying.” Acting white is definitely on the “outside” of the circle of culture, and participants described the feeling that family members want to pull the individual back inside circle.

…[Acting white] affects our culture so highly we got to deal with people that making us step up, and then we got people that are trying to pull you down from that same step up you're making. People in our families are steadily trying to pull you from that step, and they spread out from where you used to be this tight, now you're not this tight anymore.

As a result, tension is created for the person who has to choose between doing what they believe is best for their individual health or risk disrupting family and social harmony.

Discussion

Data from this study contributes to nursing knowledge in four areas including: findings related to hypertension prevention beliefs of African Americans; the utility of the TPB in understanding HTN prevention self-care in African Americans; the influence of culture on health behaviors; and the role of community level interventions in combating HTN.

Hypertension Preventive Beliefs of African Americans

Data from this study provides important information about African Americans' beliefs related to HTN prevention. Culturally prescribed norms for diet and food preparation were seen as the overriding cause of HTN. Participants expressed little attention to the role of either obesity or exercise as causative factors. The contribution of diet to BP was related to food ingredients (e.g., salt, fats) rather than to weight and the effect of weight on BP. Exercise was rarely mentioned as a prevention strategy. There seemed to be little valuing of weight control or increased physical activity across all the groups as either a preventive or control strategy. The participants' focus on diet may reflect the most prominent health instructions they have received. Leading “stressful lives” was viewed as a cause of HTN, as well as a barrier to engaging in preventive self-care. In groups with persons having higher SES, stress occurred due to busy lives from work and family commitments. Participants with lower SES reported stress related to more fundamental issues such as having the finances to meet basic needs. Despite the fact that stress was discussed as a significant concern, participants were unable to describe many strategies to relieve the stress. They just “lived with it,” suggesting an important area for nursing intervention.

Theory of Planned Behavior

Data from the current study identified positive attitudes toward the need for HTN prevention. Cognitive beliefs indicated that participants knew that changing diet, increasing exercise, and reducing stress would control BP. Data also supported the effect of perceived behavioral control on actual behavior. Participants expressed beliefs reflecting both internal and external barriers to preventive behaviors that were similar to those expressed by African Americans in other studies (Gettleman & Winkleby, 2000; Plescia & Groblewski, 2004). In previous studies with the TBP, subjective norm has demonstrated less predictive power than either attitude or perceived behavioral control in explaining African American health behaviors (Bowie et al., 2003; Jennings-Dozier, 1999; Hanson, 1999; Trost et al., 2002). This lack of predictive power may be due to limitations in how subjective norm has been conceptualized and is one reason why two reviews of the TPB called for an expansion of the normative component of the theory (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Godin & Kok, 1996). Although defined as the “perceived social pressure to engage or not engage in a behavior” (Ajzen, 2002), most studies have limited discussion of “important referents” to individuals or groups, close to the person such as a spouse, teacher, doctor, or immediate family members. The most significant finding of the current study is the strong belief expressed by participants that they are connected to a broader African American culture that extends beyond their immediate social network. The TPB was developed to explain and predict an individual's behavior, but this study found that behavior of individual African Americans cannot be understood without recognizing that it is embedded within a larger circle of culture. This data presents an expanded conceptualization of subjective norm, demonstrating the influence of culture on attitude formation and behavior.

Circle of Culture

The use of the “circle of culture” as a theme is consistent with work of scholars who find “circle” to be an important metaphor to describe a symbol of family connection. One of the first uses of the circle metaphor was by the abolitionist Fredrick Douglas who saw the circle as representing a boundary that allows individuals to find a source of identity formation while also offering a safe retreat from a hostile society. Later authors have suggested that the circle may prevent a member's individuation and growth (Dilworth-Anderson, Burton, & Klien, 2004). Even those works however, have discussed the circle as it relates to the immediate family. Data from the current study presents a broader perspective whereby the circle is expanded to include participants' sense of “fictive kinship” or “collective identify” (Ogbu, 2004).

Collective identity refers to a sense of belonging and a “we” feeling that develops through a series of shared collective experiences. Collective experiences of oppression and exploitation of African Americans have resulted in the development of a sense of a Black community that embodies their collective racial identity (Ogbu, 2004). Collective identity is expressed through attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors, and in oppressed minorities may be expressed as an “opposititional culture.” Resistance or opposition is one response minorities may use for coping with demands and expectations that they behave like dominant group members. For some African Americans this coping strategy has resulted in a resistance to “acting white” out of a fear of losing their Black cultural ways (Bergin & Cooks, 2002). The influence of “acting white” has been studied extensively in relation to minority education and psychosocial adjustment, but has received little attention in relation to health care.

Within the current study the sub-theme of “acting white” emerged in discussions surrounding the lack of trust in physicians. Despite the stated belief that physician care is needed to control BP, the overall attitude toward physicians was one of distrust, which resulted in lack of adherence to medical plans of care. Earlier work by Ajzen and Timko (1986) suggested that attitude toward physicians was too remote from action to predict behavior, but this may not be the case for African Americans who have been exposed to bias and prejudicial treatment when seeking health care (Benkert & Peters, 2005; Green, 1995; Peters, 2004; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2002). The participants in the current study discussed personal experiences, shared familial experiences, and the collective experience of the Tuskegee experiment (Jones, 1993) as examples of discrimination that have shaped their attitudes towards health care and health care providers. Research by Bowie and colleagues (Bowie et al., 2003) found that the predictive power of the TPB for African Americans was increased when a variable assessing lack of trust in providers was added to the model. Thus attitude toward providers may be a larger predictor of health behaviors in African Americans than in other groups. Instead of adding an additional variable to the model, however, it may be more helpful to expand the concept of subjective norm to include the influence of collective identify on health-related attitude and behavior.

“Acting white” also emerged as a reason for African Americans not following medical advice for HTN prevention. Beyond the issue of trust in physicians, participants thought that adhering to dietary, weight, and activity recommendations would be perceived by other African Americans as “acting white,” leaving their culture behind. Studies of academic and professional success have shown that African Americans who are considered to be “acting white” suffer sanctions including accusations of being “Uncle Toms,” personal humiliation, loss of friends, and loss of a sense of community (Ogbu, 2004). Fear of similar sanctions may stop African Americans from engaging in recommended health behaviors. Participants in the current study believed that many African Americans, in order to avoid being criticized and ostracized, would not engage in preventive self-care, even if their usual behaviors were detrimental to their health. The sub theme of “acting white” may have particular importance for these participants as all of them lived in metropolitan Detroit, which is highly segregated and has strong racial polarization (Detroit Community Data Connection, 2004). Further assessment of the transferability of this theme needs to be done in other parts of the country. Regardless of the geographic location, many African Americans will come to health care interactions with a sense of distrust making it difficult for them to disclose their concerns, as well as making it difficult for them to accept suggested interventions from the provider. Understanding the influence of the circle of culture and a sense of collective identity has numerous implications for practice. Perhaps most pressing is the need to acknowledge and address the role of discrimination in health care as has been suggested by other studies (Benkert & Peters, 2005; Smedley et al., 2002). Increased awareness of the patient/provider relationship and the possibility of an oppositional cultural response may be a critical first step in changing behavior necessary to achieve BP control.

Family and Community-level Interventions

Another important practice implication arising from the circle of culture data is that individual level interventions are most likely ineffective, especially as it relates to diet. Cultural expectations are so strong that individuals need a great deal of family and community support to be able to implement current recommended healthy practices. Sub themes within the circle of culture illustrate the difficulties faced by individual African Americans trying to engage in HTN-preventive self-care behaviors. Participants in the focus groups stated that they could use professional help in making changes. They especially wanted assistance to make culturally favored foods healthier, but still palatable to family members. They also discussed the need for support from their social network, and thought the church was an important place to begin making community-level changes. This suggestion is consistent with other studies of health promotion among African Americans (Oexman, et al., 2000; Plescia & Groblewski, 2004). Church-based obesity interventions have proven to have significant results in reducing obesity among African American women (Sbrocco et al., 2005), and adding spiritual strategies to a traditional educational intervention improved nutritional intake and physical activity in another study of African American women (Yanek, Becker, Moy, Gittelsohn, & Koffman, 2001). While the concept of faith-based interventions is not new, there is scant research on the effectiveness of such programs (Peterson, Atwood, & Yates, 2002). Further research is needed to determine if these and other types of community level interventions are more effective than individual interventions in changing self-care behaviors among African Americans. Studies targeting other types of family and group interventions also are needed.

Conclusions

The results of this study add to the growing literature regarding the utility of the TPB in understanding preventive health behaviors. The TPB provides important information for understanding intra-and inter-personal factors underlying behavior. Findings from the current study enhance that understanding by demonstrating the power of the cultural context within which attitudes and behaviors are developed. This study is the first known to discuss the role of collective identity as a factor influencing health behaviors and attitudes toward health care providers. Data from the study also adds to the literature regarding the patient/provider relationship. Based on participant responses, providers need to be more cognizant of the influence of cultural factors on individual behavior, and more sensitive to the role of mistrust in adherence to the medical plan of care. Providers also should consider expanding their level of intervention to families and communities in order to improve hypertension preventive self-care among African Americans. Given the power of cultural norms, affective interventions targeting those norms and values need to be tested to determine if they can improve preventive behaviors and decrease the disparity in hypertension outcomes.

Figure 1. Theory of Planned Behavior.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics (N = 34).

| Characteristic | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.0 (9.23) | 27-60 | |

| Education | 14.8 (3.55) | 9-22 | |

| Annual Income | |||

| <$10,000 | 4 (11.7) | ||

| $10,000-24,999 | 7 (20.6) | ||

| $25,000-49,999 | 7 (20.6) | ||

| >$50,000 | 9 (26.5) | ||

| No answer | 7 (20.6) | ||

| Self-care Behaviors | |||

| Current Smoker | 7 (18%) | ||

| Alcohol >1 drink/day | 0 (0%) | ||

| Exercise | |||

| No regular exercise | 9 (27%) | ||

| 1 - 2 days/week | 10 (29%) | ||

| 3 - 4 days/week | 8 (24%) | ||

| ≥ 5 days/week | 5 (15%) | ||

| Self-rating of Health | |||

| Less healthy than others | 11 (32%) | ||

| About the same | 7 (21%) | ||

| More healthy than others | 16 (47%) | ||

Table 2. Grand Tour Questions.

| Set I: Behavioral Beliefs |

|---|

|

| Set II: Normative Beliefs |

|

| Set III: Control Beliefs |

|

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research 1 R15 NR008489-01.

The authors wish to thank Lynette Hoskins, BSN, RN for her invaluable assistance with data collection, and Ms. Deborah Page for her transcription work.

Footnotes

The final, definitive version of the article is available at http://online.sagepub.com/

References

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago, IL: Dorsey Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Nature and operations of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:27–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: TPB diagram. 2002 Retrieved August 27, 2005, from: http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.diag.html#null-link.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Timko C. Correspondence between health attitudes and behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1986;7(4):259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin DA, Cooks HC. High school students of color talk about accusations of “acting white”. The Urban Review. 2002;34(2):113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Benkert R, Peters RM. African American women's coping with health care prejudice. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(7):863–889. doi: 10.1177/0193945905278588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CM, Rhodes RE, Nehl E, Fisher J, Sparling P, Courneya KS. Ethnicity and the Theory of Planned Behavior in the exercise domain. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(6):579–591. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie JV, Curbow B, LaVeist TA, Fitzgerald S, Zabora J. The Theory of Planned Behavior and intention to repeat mammography among African American women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2003;21(4):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Ruiz MS, O'Neill D. HIV-related behaviors among prison inmates: A Theory of Planned Behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33(12):2565–2568. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NRC, Burgess E, Choi BCK, Taylor G, Wilson E, Cléroux J, et al. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. Part 1: Methods and an overview of the Canadian recommendations. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1999;160(9 Suppl):S1–S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2002. MMWR. 2004;53(20):427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo CJ, Smith E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O, Ainsworth BE. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, McGee D, Osotimehin B, Kadiri S, et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of West African Origin. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:160–168. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel HI, Rotimi CN. Genetic epidemiology of hypertension: An update on the African Diaspora. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:S2-53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detroit Community Data Connection. Fact sheet: Race and ethnicity in the Tri-county area by selected communities and school districts. 2004 Retrieved August 25, 2005 from: http://www.datadetroit.org/documents/reports/Factsheet3_Race%20&%20Ethnicity.pdf.

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Burton LM, Klein DM. Contemporary and emerging theories in studying families. In: Bengston VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dilworth-Anderson P, Klein DM, editors. Sourcebook of family theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gettleman L, Winkleby MA. Using focus groups to develop a heart disease prevention program for ethnically diverse, low-income women. Journal of Community Health. 2000;25(6):439–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1005155329922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin C, Kok G. The Theory of Planned Behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;11(2):87–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JW. Cultural awareness in the human services: A multiethnic approach. Boston MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis N, Biddle SHJ. A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: Predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2002;24:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290(2):199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MJ. Cross-cultural study of beliefs about smoking among teenaged females. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21(5):635–651. doi: 10.1177/01939459922044090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Hacker CL. Predicting intentions to use condoms among African American adolescents: The Theory of Planned Behavior as a model of HIV risk-associated behavior. Ethnicity & Disease. 1992;2(4):371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings-Dozier K. Predicting intentions to obtain a pap smear among African American and Latina women: Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior. Nursing Research. 1999;48(4):198–205. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JH. Bad blood: The Tuskegee syphilis experiment — New and expanded edition. New York, NY: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA. Analyzing and reporting focus group results. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, Scannell AU. Planning focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Spandano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1523–1529. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oexmann MJ, Thomas JC, Taylor KB, O'Neill PM, Garvey WT, Lackland DT, et al. Short-term impact of a church-based approach to lifestyle change on cardiovascular risk in African Americans. Ethnicity & Disease. 2000;10(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Collective identity and the burden of “acting white” in Black history, community, and education. The Urban Review. 2004;36(1):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Peters RM. Racism and hypertension among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2004;26:612–631. doi: 10.1177/0193945904265816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RM, Flack JM. Salt-sensitivity and hypertension in African Americans: Implications for cardiovascular nurses. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2001;15(4):138–144. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2000.080404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J, Atwood JR, Yates B. Key elements for church-based health promotion programs: Outcome-based literature review. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19(6):401–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plescia M, Groblewski M. A community-oriented primary care demonstration project: Refining interventions for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(2):103–109. doi: 10.1370/afm.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR. QSR International Pty. Ltd; Doncaster, Victoria, Australia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sbrocco T, Carter MM, Lewis EL, Vaughn NA, Kalupa KL, King S, et al. Church-based obesity treatment for African American women improves adherence. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15:246–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempos CT, Rehm J, Wu T, Crespo CJ, Trevisan M. Average volume of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality in African Americans: the NHEFS cohort. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(1):88–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046597.92232.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY. In: Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare Institute of Medicine Board on Health Sciences Policy Report. Nelson AR, editor. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smitherman G. Black language and culture: Sounds of soul. New York, NY: Harper and Row Publishers; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Stamler J. The INTERSALT study: Background, methods, findings, and implications. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1997;65(Suppl):626S–642S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.2.626S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2004. NSDUH Series H-25, DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3964. [Google Scholar]

- Tran VT, Aroian KJ. Developing cross-cultural research instruments. Journal of Social Work Research and Evaluation. 1999;1(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Trost SG, Pate RR, Dowda M, Ward DS, Felton G, Saunders R. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity in White and African American girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(3):226–233. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, et al. Primary prevention of hypertension: Clinical and Public Health Advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1882–1888. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: Faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(Suppl 1):68–81. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]