Abstract

Background

Skeletal myoblast (SKMB) transplantation has been proposed as a therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy due to its possible role in myogenesis. The relative safety and efficacy based on location within scar is not known. We hypothesized that SKMB transplanted into peripheral scar (compared to central scar) would more effectively attenuate negative left ventricular (LV) remodeling but at the risk of arrhythmia.

Methods

34 New Zealand White rabbits underwent mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD) ligation to produce a transmural LV infarction. One month after LAD ligation SKMBs were injected either in the scar center (n=13) or scar periphery (n=10) and compared to saline injection (n=11). Holter monitoring and MRI was performed pre-injection; Holter monitoring was continued until two weeks post injection, with follow-up MRI at one month.

Results

Centrally-treated animals demonstrated increased LV end systolic volume, end diastolic volume and mass that correlated with injected cell number. There was a trend toward attenuation of negative LV remodeling in peripherally-treated animals compared to vehicle. Significant late ectopy was seen in several centrally-injected animals with no late ectopy seen in peripherally-injected animals.

Conclusions

We noted untoward effects with respect to negative LV remodeling following central injection, suggesting that transplanted cell location with respect to scar may be a key factor in the safety and efficacy of SKMB cardiac transplantation. Administration of SKMBs into peripheral scar appears safe with a trend toward improved function in comparison to sham injection.

Keywords: cell therapy, heart failure, myoblast

INTRODUCTION

Functional benefit to skeletal myoblast (SKMB) therapy as a treatment for ischemic cardiomyopathy has been described in multiple animal models including rodent1–4, rabbit5,6, sheep7, and dog8 models, and in recent human trials9–15. Global and regional effects reported include increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickening16, increased compliance5,17–19, increased contractility at the infarction site5,17,19,20, increased myocardial tissue velocities, decreased left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) and left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV) in a dose-dependent fashion21.

Therapeutic benefits notwithstanding, a potential risk noted in the earliest human SKMB trials was susceptibility to arrhythmia9. Significant arrhythmias have not been noted in animal studies to date, with the exception of induction of arrhythmia by cardiac pacing in rodent models22,23. While this endpoint is difficult to attribute to SKMB therapy given the predisposition to arrhythmia after cardiac injury, the importance of placement of SKMBs within scar cannot be ignored. One of the proposed strengths of SKMBs is their survivability in hypoxic environments24, making them an attractive option for placement within scar. However, electrical insulation following transplantation into central scar could render myoblasts ineffective if contraction and relaxation were dependent on electrical or mechanical cues from neighboring viable myocardium. The ability of transplanted myoblasts to contract in synchrony with native cardiomyocytes has not been conclusively proven, although this has been suggested by sonomicromanometric regional measurements5. Furthermore, it is not known whether the improved diastolic properties seen after SKMB transplantation are due to active relaxation of the transplanted cells or change in the viscoelastic properties of the heart wall, possibly due to remote modulation by secondary factors, such as cytokines or angiogenic factors25,26.

Conduction capabilities of SKMBs may be highly dependent on their location with respect to viable myocardium. Although immature SKMBs do transiently express connexin-43 (CN43), its subsequent down-regulation upon differentiation into myotubes has been proposed as a cause of electrical instability due to ineffective coupling with cardiocytes27. Convincing evidence exists in ex vivo models that exogenous myoblasts remain electrically uncoupled from cardiomyocytes at greater than 4 weeks of intracardiac transplantation, with the exception of myoblast-cardiomyocyte fusion28,29. While the absence of interconnecting gap junctions may render impulse propagation extremely inefficient, the electrical activity of the transplanted cells may not be truly insulated from native myocardium.

For this reason, we used a coronary ligation model to determine the influence of injection location with respect to scar on the safety and efficacy of SKMB transplantation. SKMBs, as electrically active cells, could theoretically create re-entrant aberrant rhythms that produce a clinically significant ventricular arrhythmia when transplanted in proximity to viable myocardium. Conversely, cells transplanted into central scar may harbor reentrant rhythms, but with decreased likelihood of propagation to cardiocytes. Our model offers additional insight as to the cues for functionality of transplanted cells, demonstrating whether transplanted cell contraction is initiated by depolarization of adjacent native myocardium, or whether transplanted myoblast contraction is based on stretch physiology, achieving synchronous contraction with native ventricle on the basis of parameters such as end-diastolic wall tension and volume. In addition, we attempted to establish a risk profile of SKMB arrythmogenicity based on treatment location with respect to scar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Infarction model

34 New Zealand White rabbits (aged ~3 months, female, weighing ~3.5 kgs) were ligated at the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery to create an area of infarction. All rabbits were intravenously loaded with 4mg/kg of amiodarone and maintained on a dobutamine infusion (0.01–0.04mcg/kg/min) perioperatively. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 86–23, revised 1996) and under study protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota.

Cell culture, cell labeling and characterization

At the time of injury, 5g of soleus muscle were removed from the left hind limb and placed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Mediatech, Herndon, VA) and refrigerated at 4°C until processing by microdissection to yield 1–2g of tissue per 30ml of growth media (low glucose, 20% horse serum, 0.05% gentamycin in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)). Tissue was plated on 75mm plates (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) with complete media replacement every two days. When myoblast outgrowth achieved 75% plate confluence, cells were trypsinized (TrypleE Express, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and expanded by re-plating in a 1:3 ratio to achieve a total of 5–10×107 total cells by passage six. Cells were Fe-oxide labeled with Ferridex™ (Berlex, Wayne, NJ, USA) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Invitrogen) as previously described30.

Cell harvesting and delivery

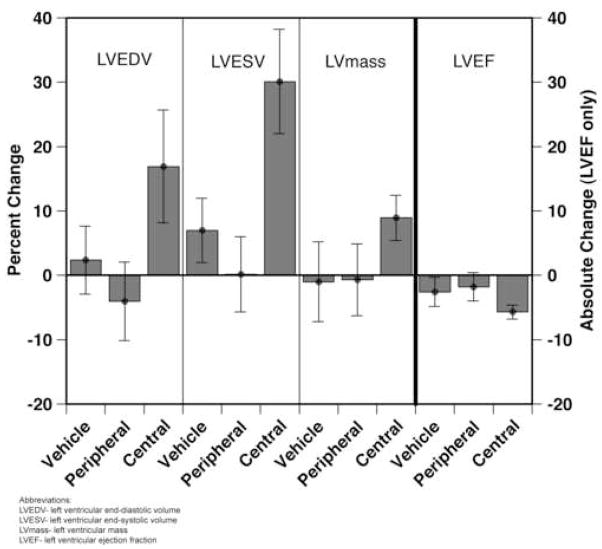

Labeled cells were harvested at 1 month post-infarct and concentrated into 750μl of PBS in a 1ml syringe with 27.5 gauge needle. All animals were administered an amiodarone bolus (4mg/kg) prior to skin incision and maintained on dobutamine (2mcg/kg/min) intraoperatively. A repeat thoracotomy was performed through the old incision and sufficient exposure was obtained with rib retractors to visualize anterolateral scar. Dimensions of scar were determined by review of Gd-enhanced MRI performed 48 hours prior, identification of the superior extent of scar based on the location of the prolene suture, and the surgeon’s (JDM) assessment of the color and dyskinetic contours of the myocardial surface. Cell delivery was performed either centrally via 6 injections or peripherally at the 4, 8 and 12 o’clock positions relative to scar, with two injections administered per location (Figure 1A). In vehicle-treated animals, 750μl of isotonic saline vehicle was injected both peripherally and centrally via 6 total injections. A wheal of cellular mass was observed in all injected hearts.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of central, peripheral, and vehicle injection locations. (B) Experimental timeline depicting treatment at one month post-infarct, with cardiac MRI at 2 days pre-treatment and one month post-treatment. Holter monitoring is indicated at 2 days prior to treatment and continues for 2 weeks post-treatment.

Cardiac MRI

Cardiac imaging with a small animal ECG-gating system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook NY, USA) was performed 1 month after ligation and 1 month after treatment with a 1.5T scanner (Siemens Avanto, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) (Figure 1B). Global LV function was determined by retro-gated True-FISP cine with 25 phases covering the cardiac cycle. Segmental wall thickening was determined by the difference of epicardial and endocardial contours in LV end-systole and end-diastole in 12 total segments per axial slice. Dyskinetic wall thickening was defined as a negative value when subtracting end-systolic from end-diastolic thicknesses. Scar was imaged by inversion recovery segmented FLASH with an inversion time chosen to null the signal from normal myocardium (~170ms) after 10 minutes following a slowly injected bolus of 0.4 mmol/kg gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Berlex, Wayne NJ, USA). Image measurement and analysis was performed by two blinded reviewers (CS, RM) using MASS software version 4.0 (University of Leiden, The Netherlands).

Holter Monitoring

All animals had a 3-channel, 7-lead battery-operated DRE 180 Holter monitor (Northeast Monitoring, Houston, TX) secured transcutaneously by 4-0 stainless steel wires and reinforced by 3M™ coban self-adhering tape. The monitoring device was placed in a mesh vest (Lomir Biomedical, Canada) worn by the animal with an external zippered pocket. Holter measurements were taken preoperatively for 24 hours at 1–2 days prior to cell injection and continuously post-injection from the time of chest closure to a maximum duration of 14 days (Figure 1B). Holter data was analyzed on a Northeast Holter Monitoring LX PRO system, followed by blinded manual review (RM).

Immunohistochemistry

Hearts from animals euthanized at 1 month after cell administration were stored in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C, and subsequently snap-frozen in OCT medium and sectioned at 5μm. Sections at 100μm intervals were stained with Prussian blue to determine presence of Fe-labeled cells and counterstained with Masson trichrome. On those slides where Fe-labeled cells where evident, adjacent sections were stained with anti-rabbit skeletal myosin heavy chain (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) after blocking with 1% FBS in PBS for 30 minutes. Secondary detection was by Xenon anti-IgG1 with a 488 fluorophore (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After incubation for 2 hours, slides were washed with PBS for 10 minutes × 3 and secondarily fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Nuclear counterstaining was performed with Vectashield mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni or Tukey-Kramer tests (where appropriate) were used for comparison of multiple groups. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using JMP for Windows v4.0.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Validation of surgical model

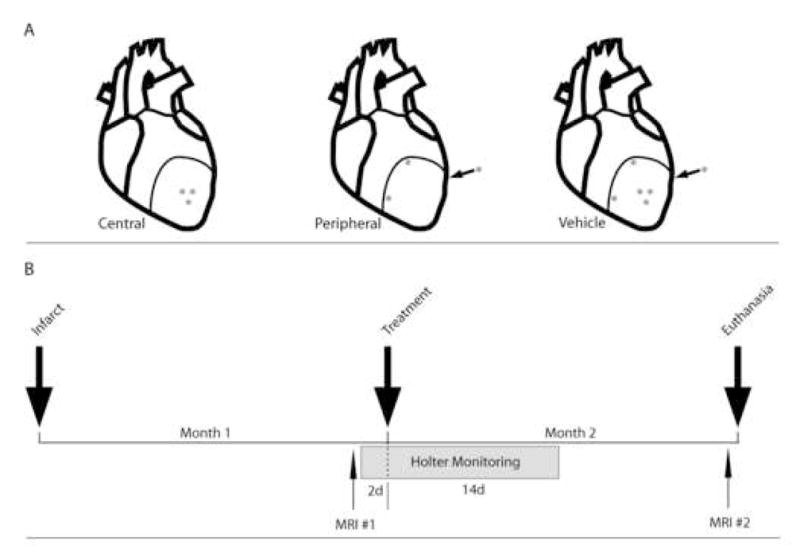

At 1 month post-infarction, a consistent degree of injury was observed in all groups (Table). Because we desired autologous cell therapy, randomization was not possible. At 1 month post cell injection, deposits of Fe-labeled cells in myocardium were visualized as signal voids within the myocardium on T1-weighted MRI. Their relative position to scar, either peripheral (Figure 2A, B) or central (Figure 2C, D), was verified after intravenous Gd administration. Histologic confirmation of Fe-labeled cells by Prussian blue stain with Masson trichrome counterstain in either peripheral (Figure 2E) or central (Figure 2F) configurations correlated with the individual animal’s MRI results. 5μm frozen sections adjacent to sections demonstrating Fe-labeled cells were positive for skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain (Figure 2I, J). To ensure these skeletal myosin heavy chain-expressing cells were also iron-labeled, coverslips were removed and subsequently stained with Prussian blue and Masson trichrome (Figure 2G, H).

Table.

Pre-treatment values

| peripheral | central | sham | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| animals (n) | 10 | 13 | 11 | |

| LVEDV (ml) | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 |

| LVESV (ml) | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 |

| LVEF (%) | 51.5 ± 12.4 | 51.0 ± 1.3 | 48.8 ± 1.8 | 0.5 |

| LVMASS (gm) | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | >0.5 |

| Scar/EDV | 0.06 ± 0 | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular mass (LVMASS), scar size is expressed as a ratio of scar to end-diastolic volume (Scar/EDV)

Figure 2.

T1-sequenced MRI demonstrating Fe-labeled cells in a peripheral (A, axial) and central (C, longitudinal) configuration. Gd contrast sequences (white) show the relative position of injected cells (arrows and signal void) to scar (B, D). Prussian blue with Masson’s Trichrome counterstaining of hearts sections of these animals demonstrates iron-labeled cells adjacent to viable myocardium in the peripheral configuration (E) and cells localized within scar following central injection (F). 60× magnification of boxed areas in E, F demonstrate same-cell specificity for Fe-labeling (G, H) and heavy chain skeletal myosin (I, J). Scale bars represent 100μm (E, F), 25μm (G–J).

Negative LV remodeling associated with segmental dyskinesis

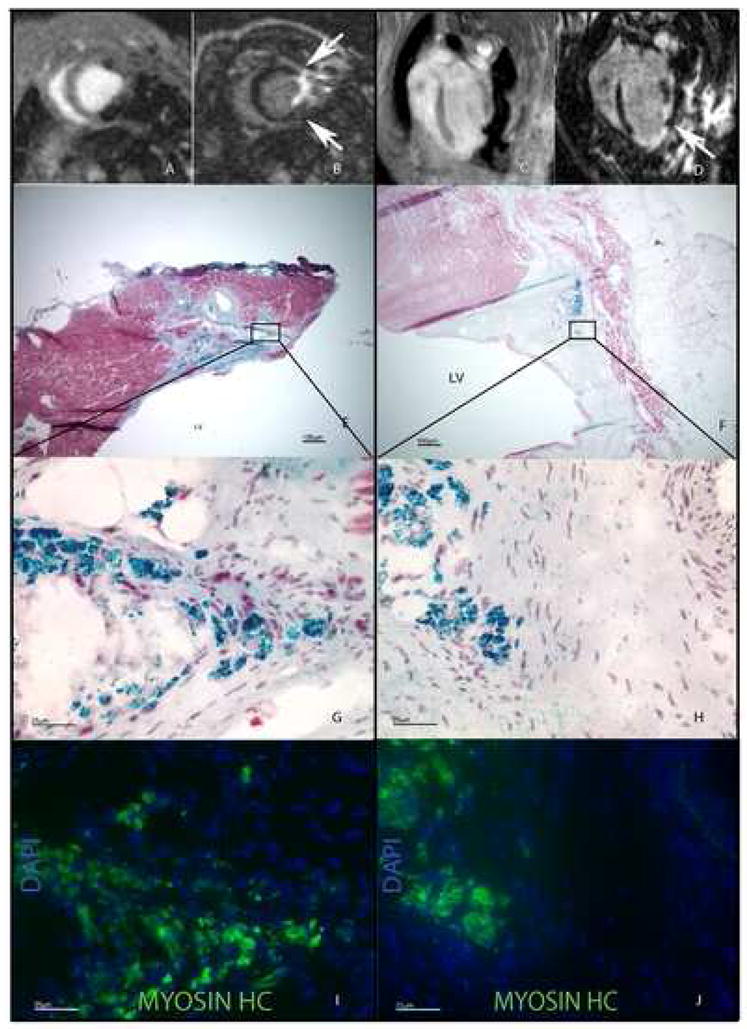

There was no significant difference in the median number of SKMBs administered to peripheral (75±15 × 106) or central (70±7.6 × 106) cell administration groups. We noted an untoward effect in centrally-transplanted animals, resulting in a significantly higher percent change in LVESV (central vs. peripheral, 29.9%, p=0.007, central vs. sham, 23.1%, p=0.02) and trends towards a significantly higher percent change in LVEDV (central vs. peripheral, 21.0%, p=0.06, central vs. sham, 14.5%, p=0.1), left ventricular mass (central vs. peripheral, 9.6%, p=0.2, central vs. sham, 9.9%, p=0.2), and an absolute reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (central vs. peripheral, −3.9%, p=0.1, central vs. sham, −3.1%, p=0.2) at one month after injection (Figure 3). Trends favoring peripheral administration of cells did not achieve significance in comparison to sham injection.

Figure 3.

Global function at one month post-treatment. LVESV, LVEDV, and LV mass are expressed as percent change. LVEF is expressed as absolute difference. Bars represent mean values +/− SEM.

In an effort to explain the negative effect seen in centrally-transplanted animals, we performed a sub-analysis of dyskinetic wall segment thickening at the center of scar. Examining 12 total segments per axial slice, we found a slightly greater mean number of dyskinetic segments in the area of injury among centrally-injected animals than those undergoing peripheral or vehicle injection (central vs. peripheral, 2.3±0.8 vs. 0.8±0.4, p=0.09; vs. vehicle, 2.0±0.58, p>0.5).

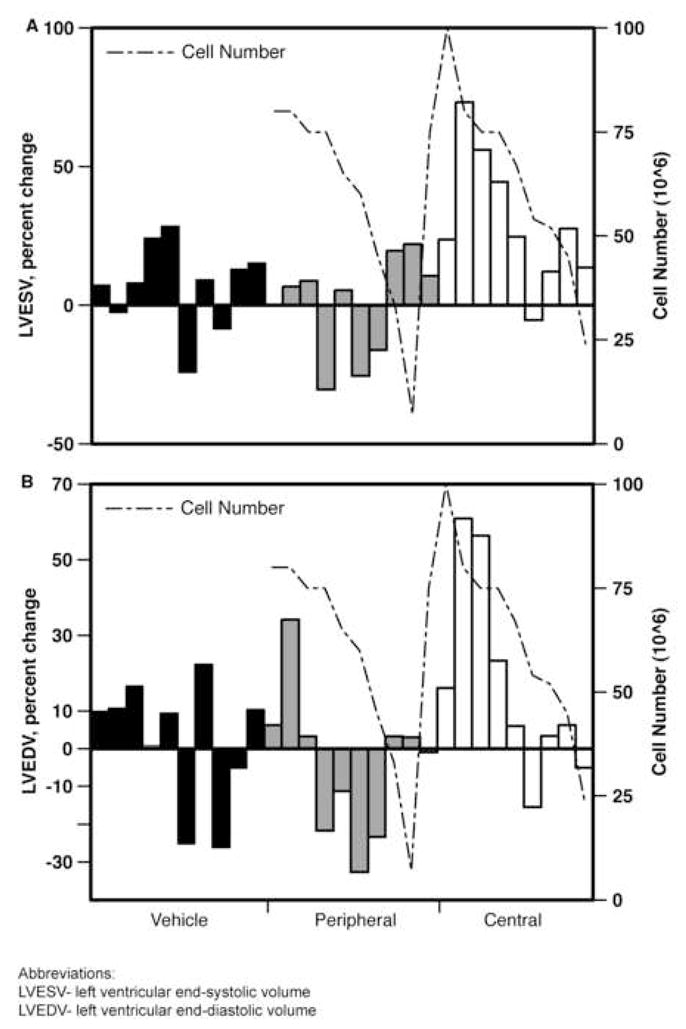

Negative LV remodeling associated with administered cell number

Analysis of individual subjects demonstrated that the measures of negative LV remodeling in centrally-treated animals (LVESV and LVEDV) correlated with the number of SKMBs administered (Figure 4A, B). In the peripherally-treated animals, this correlation was the opposite - higher numbers of cells resulted in greater attenuation of negative LV remodeling. To determine whether approximately equivalent cell numbers remained within the myocardium in both treatment groups, we labeled SKMBs with lanthanide particles (Europium™, BioPALs, Worcester, MA, USA) in 2 animals 24 hours prior to injection (1.25×108, central, 1.2×108, peripheral) and submitted whole hearts for radioactive label quantification at 2 weeks. Nearly equivalent values of retained cells (2.2×107, both animals) were found in whole heart specimens.

Figure 4.

LVESV (A) and LVEDV (B), expressed as percent change from pre-treatment values by individual subject. Correlation with administered SKMBs is shown.

Electrical instability in scar-isolated myoblasts

Median duration of continuous Holter monitoring (days) between all groups was similar (central: 9, (range: 3–14), peripheral: 8, (5–13), vehicle: 12, (3–14)). The majority of animals did not experience any ventricular ectopy during the monitoring period. Excluding those animals with pre-treatment ectopy, no difference in early ectopy (<48hrs post-transplantation), was seen between treatment groups (central-2/8, peripheral-1/8, vehicle-1/8). Similarly, there was no difference in the number of animals that experienced late (>48hrs post-transplantation) ectopy (central-2/8, peripheral-2/8, vehicle-1/8). Of the 2 centrally-treated animals showing late ectopy, one exhibited sustained ventricular tachycardia and the other demonstrated 820 isolated premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). The 2 peripherally-transplanted animals with late ectopy exhibited 1 PVC each. The one vehicle-treated animal with late ectopy exhibited 35 isolated PVCs. There was no correlation between number of cells administered and occurrence of ectopy.

DISCUSSION

Autologous SKMB transplantation has been extensively studied in multiple animal models and several human clinical trials as a potential therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. While myoblast engraftment has been demonstrated at distant timepoints12, the mechanism of benefit has not been rigorously studied. It has been demonstrated that the contractile activity of transplanted SKMBs remains independent of native cardiocytes ex vivo28, suggesting that the observed therapeutic benefit is less likely due to active mechanical properties of engrafted cells. Given this observation, it is logical that the efficacy of transplanted SKMBs would be affected by their proximity to native myocardium as this would enhance cell-cell signaling by paracrine means.

We used proof of injection location to define what may be a key variable in the safety and efficacy of this potential therapy, demonstrating that SKMBs transplanted in relative isolation from viable myocardium (e.g., central scar) produces a dose-dependent, untoward effect on negative LV remodeling. Conversely, a beneficial trend towards attenuation of negative remodeling is observed when SKMBs are transplanted adjacent to viable myocardium (e.g., periphery of scar). While our model does not define the mechanism by which location of transplanted SKMBs influences efficacy, the relationship of segmental dyskinesis and injection location is of interest, although no treatment groups demonstrated significantly greater dyskinesis than vehicle injection. There was no significant difference between the treatment groups with respect to scar volume (data not shown), suggesting that central administration of cells did not merely expand scar with non-functioning cell mass.

Our results should be viewed in the context of the recent phase II Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial, in which patients with heart failure (LVEF 15–35%) undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting alone were found to have significantly lower LVEDV and LVESV following high dose (800 × 106) SKMB intramyocardial transplantation in comparison to placebo15. Additionally, the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events and time-to-first ventricular arrhythmia did not differ between SKMB and placebo groups, although the trial was not powered demonstrate this significantly. While this study overall showed favorable effects of SKMB transplantation in patients with significant heart failure without compromising safety of patients, the influence of location with respect to scar was not explicitly investigated. Our study suggests that cell injection location with respect to the zone of injury is relevant to therapeutic benefit, or conversely, to avoiding an adverse outcome. Similarly to the MAGIC trial, we could not confidently observe any relationship between arrhythmia and SKMB injection.

Our study has several limitations: the cardiac injury model, utilizing a mid-LAD ligation, produced acceptable survival while yielding a measurable degree of injury as determined by MRI at 1 month. However, due to poor survivability following a proximal LAD ligation, we were unable to produce a significant degree of heart failure. Consequently, this model may be relevant to patients in which cardiac injury is not overwhelming.

An additional limitation of this study is that the putative arrhythmogenicity of SKMB transplantation is a very difficult end point to establish in vivo, and it should be emphasized that the majority of treated animals experienced no serious arrhythmic events. We expected that if SKMB injection were causative in arrhythmia, the proximity of transplanted cells to surviving myocardium could be a critical factor. One possible reason could be that SKMBs transplanted into central scar develop re-entrant rhythms that eventually escape to neighboring viable myocardium despite the insulation of surrounding scar, whereas SKMBs transplanted into viable myocardium do not develop such re-entry due to greater electrophysiologic integration with cardiomyocytes. While this was not the case in the majority of animals, this phenomenon was supported by the two centrally-treated animals with significant late ventricular arrhythmia.

Overall, we found no benefit to transplantation of SKMBs in central scar under relative electrophysiologic isolation from native myocardium, and observed significantly worse negative remodeling at one-month post treatment. The precise mechanism for this cannot be explained in our animal model, although a trend towards segmental dyskinesis was observed corresponding to central injection. Peripheral scar transplantation of SKMB produced a nonsignificant trend towards attenuation of negative LV remodeling without apparent additional incidence of arrhythmia. These findings that location of administration is of importance in future cell therapy models as well as clinical trials, and the benefit of SKMB transplantation may depend on injection proximity to surviving myocardium.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI grants: R01 HL063703-05 (Taylor) and NRSA 5F32HL082134-02 (McCue) and funding from the Medtronic Foundation to the Center for Cardiovascular Repair at the University of Minnesota. We would like to acknowledge the statistical assistance provided by Angelika Gruessner, PhD, Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, as well as Andrey G. Zenovich, MSc, Center for Cardiovascular Repair.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marelli D, Desrosiers C, el-Alfy M, Kao RL, Chiu RC. Cell transplantation for myocardial repair: an experimental approach. Cell Transplant. 1992;1(6):383–90. doi: 10.1177/096368979200100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huwer H, Winning J, Vollmar B, et al. Long-term cell survival and hemodynamic improvements after neonatal cardiomyocyte and satellite cell transplantation into healed myocardial cryoinfarcted lesions in rats. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(7):757–67. doi: 10.3727/000000003108747361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye L, Haider H, Jiang S, et al. Reversal of myocardial injury using genetically modulated human skeletal myoblasts in a rodent cryoinjured heart model. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(6):945–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanemitsu N, Tambara K, Premaratne GU, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 enhances the efficacy of myoblast transplantation with its multiple functions in the chronic myocardial infarction rat model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(10):1253–62. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DA, Atkins BZ, Hungspreugs P, et al. Regenerating functional myocardium: improved performance after skeletal myoblast transplantation. Nat Med. 1998;4(8):929–33. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Bos EJ, Davis BH, Taylor DA. Transplantation of skeletal myoblasts for cardiac repair. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(11):1217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghostine S, Carrion C, Souza LC, et al. Long-term efficacy of myoblast transplantation on regional structure and function after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;106(12 Suppl 1):I131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He KL, Yi GH, Sherman W, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation improved hemodynamics and left ventricular function in chronic heart failure dogs. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(11):1940–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(7):1078–83. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herreros J, Prosper F, Perez A, et al. Autologous intramyocardial injection of cultured skeletal muscle-derived stem cells in patients with non-acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(22):2012–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dib N, McCarthy P, Campbell A, et al. Feasibility and safety of autologous myoblast transplantation in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cell Transplant. 2005;14(1):11–9. doi: 10.3727/000000005783983296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagani FD, DerSimonian H, Zawadzka A, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblasts transplanted to ischemia-damaged myocardium in humans. Histological analysis of cell survival and differentiation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(5):879–88. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminiak T, Fiszer D, Jerzykowska O, et al. Percutaneous trans-coronary-venous transplantation of autologous skeletal myoblasts in the treatment of post-infarction myocardial contractility impairment: the POZNAN trial. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(12):1188–95. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siminiak T, Kalawski R, Fiszer D, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for the treatment of postinfarction myocardial injury: phase I clinical study with 12 months of follow-up. Am Heart J. 2004;148(3):531–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagege AA, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, et al. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure: long-term follow-up of the first phase I cohort of patients. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I108–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Bos EJ, Thompson RB, Wagner A, et al. Functional assessment of myoblast transplantation for cardiac repair with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(4):435–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson RB, Emani SM, Davis BH, et al. Comparison of intracardiac cell transplantation: autologous skeletal myoblasts versus bone marrow cells. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II264–71. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087657.29184.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkins BZ, Heuman MT, Meuchel JM, Cottman MJ, Hutcheson KA, Taylor DA. Myogenic cell transplantation improves in vivo regional performance in infarcted rabbit myocardium. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18(12):1173–80. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins BZ, Hueman MT, Meuchel J, Hutcheson KA, Glower DD, Taylor DA. Cellular cardiomyoplasty improves diastolic properties of injured heart. Journal Of Surgical Research. 1999;85(2):234–42. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis MJ, Emani SM, Colgrove SL, Glower DD, Taylor DA. Systolic contraction within aneursymal rabbit myocardium following transplantation of autologous skeletal myoblasts. J Surg Res. 2006;135(1):202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tambara K, Sakakibara Y, Sakaguchi G, et al. Transplanted skeletal myoblasts can fully replace the infarcted myocardium when they survive in the host in large numbers. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II259–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087430.17543.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouts K, Fernandes B, Mal N, Liu J, Laurita KR. Electrophysiological consequence of skeletal myoblast transplantation in normal and infarcted canine myocardium. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(4):452–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills WR, Mal N, Forudi F, Popovic ZB, Penn MS, Laurita KR. Optical mapping of late myocardial infarction in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(3):H1298–306. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00437.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohin S, Stary CM, Howlett RA, Hogan MC. Preconditioning improves function and recovery of single muscle fibers during severe hypoxia and reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281(1):C142–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murtuza B, Suzuki K, Bou-Gharios G, et al. Transplantation of skeletal myoblasts secreting an IL-1 inhibitor modulates adverse remodeling in infarcted murine myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(12):4216–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306205101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki K, Murtuza B, Smolenski RT, et al. Cell transplantation for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction using vascular endothelial growth factor-expressing skeletal myoblasts. Circulation. 2001;104(12 Suppl 1):I207–12. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinecke H, Minami E, Virag JI, Murry CE. Gene transfer of connexin43 into skeletal muscle. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15(7):627–36. doi: 10.1089/1043034041361253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leobon B, Garcin I, Menasche P, Vilquin JT, Audinat E, Charpak S. Myoblasts transplanted into rat infarcted myocardium are functionally isolated from their host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7808–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232447100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubart M, Soonpaa MH, Nakajima H, Field LJ. Spontaneous and evoked intracellular calcium transients in donor-derived myocytes following intracardiac myoblast transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(6):775–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI21589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Bos EJ, Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, et al. Improved efficacy of stem cell labeling for magnetic resonance imaging studies by the use of cationic liposomes. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(7):743–56. doi: 10.3727/000000003108747352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]