Abstract

Metallothioneins are central for the metabolism and detoxification of transition metals. Exposure to mercury during early neurodevelopment is associated with neurocognitive impairment. Given the importance of metallothioneins in mercury detoxification, metallothioneins may be a protective factor against mercury-induced neurocognitive impairment. Deletion of the murine metallothionein-1 and metallothionein-2 genes causes choice accuracy impairments in the 8-arm radial maze. We hypothesize that deletions of metallothioneins genes will make metallothionein-null mice more vulnerable to mercury-induced cognitive impairment. We tested this hypothesis by exposing MT1/MT2-null and wildtype mice to developmental mercury (HgCl2) and evaluated the resultant effects on cognitive performance on the 8-arm radial maze. During the early phase of learning metallothionein-null mice were more susceptible to mercury-induced impairment compared to wildtype. Neurochemical analysis of the frontal cortex revealed that serotonin levels were higher in metallothionein-null mice compared to wildtype mice. This effect was independent of mercury exposure. However, dopamine levels in mercury exposed metallothionein-null mice were lower compared to mercury-exposed wildtype mice. This work shows that deleting metallothioneins increase the vulnerability to developmental mercury-induced neurocognitive impairment. Metallothionein effects on monoamine transmitters may be related to this cognitive effect.

Keywords: Metallothionein, mercury, learning, radial-arm maze, dopamine, serotonin

Introduction

Low-level environmental toxicant exposure is widespread in our society. However, the biological consequence of low-level toxicant exposure varies among individuals. Heightened susceptibility to intoxication may be mediated by genetic variations within the population. When considering gene × environment interactions, initial targets for analysis are those genes involved in the distribution and detoxification of environmental toxicants.

Metallothioneins are low molecular weight, cysteine-rich proteins central to the metabolism and detoxification of transition metals. There are four classes of vertebrate metallothioneins; MT1, MT2, MT3 and MT4. Multiple isoforms of MT1 and MT2 are present in humans [42]. The primary functions of metallothioneins are to maintain homeostatic levels of essential metals and detoxify non-essential metals [16,23,30]. MT1 and MT2 protect the central nervous system from damage induced by interleukin 6, 6-aminonicotinamide, kainic acid and physical injury [4,10,33]. Studies using MT1/MT2-null mice have also shown that MT1 and MT2 protect cells from damage induced by oxidative stress [25].

Developmental exposure to transition metals such as mercury is causes cognitive impairment [2,3,14]. Organic mercury (methyl or ethyl) are much more potent neurotoxicants than metallic mercury, but metallic mercury (HgCl2) has neurotoxic effects as well. With low-level mercury exposure there is considerable variation in toxic response. This may be due to heterogeneity of control over the distribution and detoxification of mercury.

To study the biological function of metallothionein, transgenic mice have been created in which both MT1 and MT2 genes were deleted [28]. Under ambient conditions MT1/MT2-null mice do not exhibit obvious physical abnormalities. However MT1/MT2-null mice have lower levels of zinc in serum and liver [24,37], learning impairment [26] and have an increased sensitivity to metal toxicity and environmental stress [31]. The current study was conducted to determine the interactive effects of the MT1/MT2-null genotype with exposure to neurotoxic metal mercury. We hypothesize that the cognitive impairment caused by mercury would be enhanced in the metallothionein null mice.

Methods

Mice

MT1/MT2-null mice from the parental 129 strain were used for behavioral and neurochemical analysis. Wild-type 129 mice were used as controls. MT1/MT2-null and wild-type mouse breeding pairs were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). The mice used in the current study were bred homozygote by homozygote in our lab at Duke University. A total of 158 mice (MT1/MT2-null and wild-type) from forty-two litters were used in the study. Mice were housed in same sexed groups of 3–4 in a Thorne ventilated cage rack in plastic cages. Cages were maintained at 22±2 C° on a 12:12 day:night lighting cycle. Both MT1/MT2-null and wild-type mice were maintained on the same rodent chow with ad lib access to water. The care of the animals and the experimental procedures were in accordance with an approved animal protocol and in accord to institutional and federal animal care guidelines.

Mercury Treatment

Mice from wild-type and MT1/MT2-null litters were randomly assigned to dosing groups (0, 2 and 5 mg/kg mercuric chloride). Only one male and one female from each litter received 0, 2 and 5 mg/kg mercuric chloride. The doses were distributed within each litter by sex as to not confound the litter effects with mercury effects. Mice were injected subcutaneously once per week during postnatal weeks 1–3 at doses of 0, 2 and 5 mg/kg of mercuric chloride (HgCl2) in a volume of 0.01 ml/g dissolved in sterile normal saline. The mice were tested in cohorts with both male and female mice representing the three doses tested at the same time. The number of animals tested at any given time depended to the breeding schedule and the number of offspring.

Radial-arm Maze

At the age of three months the mice were tested on the radial-arm maze in order to assess spatial learning and memory. The maze was made of wood (painted black) with a center platform 12 cm in diameter, with eight extending arms (24 × 4 cm). The maze was elevated 25 cm from the floor and was located in a room with extra-maze visual cues. Food cups, located at the ends of each of the arms, were baited with a small piece of a sweetened cereal (Kellogg’s Froot Loops®).

Before training on the radial-arm maze the mice were adapted to handling and had exposure to the food reinforcements while restricted to the center of the maze to insure that they would consume the reinforcements. Spatial learning and memory was assessed with the win-shift task in which all eight of the arms were baited at the beginning of the session. Since the baits are not replaced, each arm entry is only rewarded once. Prior to testing, the mouse was placed in the center of the maze in an opaque cylinder, 8 cm in diameter and 10 cm high for 10 seconds. Testing began after the cylinder was lifted and the mouse was free to explore the maze. Arm choices were recorded after all four paws crossed completely into an arm. The session lasted until the mouse entered all eight arms or 300 seconds had elapsed. The choice accuracy measure is the number of correct arm entries before an error is made (Entries to Repeat). Response latency was assessed by the average number of seconds per arm entry.

Neurochemical Analysis

After the end of the behavioral testing the mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation and their frontal cortices were analyzed for monoamine levels. Frontal cortex samples (determined as 3 mm of tissues posterior from the front of the brain: weights ranging 10–15 mg of tissue) were collected and homogenized with an ultrasonic tissue homogenizer in a 0.1N Perchloric Acid/100 mM EDTA solution (10X volume/tissue weight). After column purification, to remove solid cellular particulate, the homogenate was diluted 25X with purified water and dopamine and serotonin concentrations were determined with HPLC. The HPLC system used consisted of an isocratic pump (model LC1120, GBC Separations), a Rheodyne injector (model 7725i) with a 20 μl PEEK loop, and an INTRO amperometric detector (Antec Leyden). The electrochemical flow cell (model VT 03, Antec Leyden) had a 3mm glassy carbon working electrode with a 25 μm spacer, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The cell potential was set at 700 mV. The signal was filtered with a low pass in-line noise killer, LINK (Antec Leyden) set at a 14 s peak width and a cut off frequency of 0.086 Hz. The signal is integrated using the EZChrom elite chromatography software (Scientific Software Inc). The injector, flow cell, and analytical column were placed in the Faraday-shielded compartment of the detector where the temperature is maintained at 30°C. The stationary phase was a reverse phase BDS Hypersil C18 column 100 mm × 2.1 mm, with 5 μm particle size and 120 Å pore size (Keystone Scientific). The mobile phase was 50 mM H3PO4, 50 mM citric acid, 100 mg/L 1-octanesulfonic acid (sodium salt), 40 mg/L EDTA, 2mM KCl and 3% methanol, corrected to pH 3.0 with NaOH. The mobile phase was continually degassed with a Degasys Populaire on-line degasser (Sanwa Tsusho Co. Ltd.) and delivered at a flow rate of 0.26 ml/min.

Statistical Analysis

The behavioral and neurochemical data were assessed by analysis of variance. The between subjects factors were mercury treatment, genotype and sex. Repeated measures for the behavioral data were session blocks. The dependent measures for the radial-arm maze acquisition were entries to repeat (the number of correct entries before the first error) and seconds per arm entry. The threshold for significance was p<0.05. As recommended by Snedecor and Cochran [41] interactions with p<0.10 were followed up tests of the simple main effects of each factor in the interaction keeping with a final threshold for significance of p<0.05.

Results

Radial-Arm Maze Learning

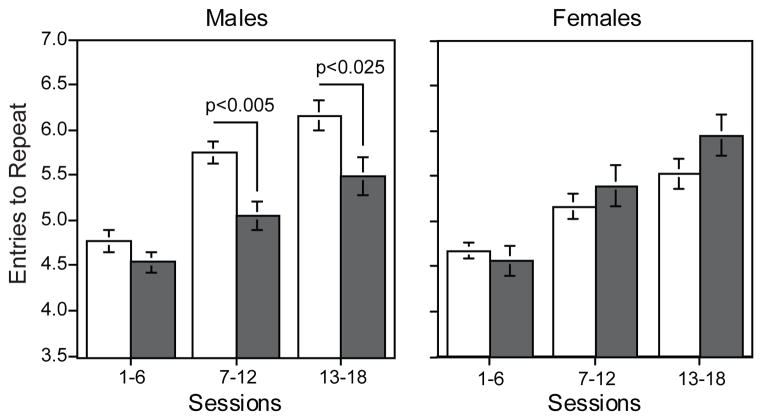

There was a significant genotype × sex interaction with respect to choice accuracy in the 8-arm radial maze (F(1,141)=9.90, p<0.005). Tests of the simple main effects of accuracy (entries to repeat, ETR) averaged over the 18 sessions of training showed a significant (F(1,141)=10.41, p<0.005) reduction in choice accuracy in MT1/MT2-null males (ETR =5.03±0.11) compared to wild-type males (ETR=5.56±0.10; not shown). There was also a differential effect of genotype × sex interaction over the sessions blocks of training (Genotype × Sex × Session block F(2,284)=4.27, p<0.025). Follow-up tests of genotype effects on accuracy in the males showed no significant effect on accuracy during sessions 1–6, but significant impairments in sessions 7–12 (F(1,141)=9.30, p<0.005) and sessions 13–18 (F(1,131)=6.77, p<0.025). In contrast, choice accuracy in females was not significantly affected by genotype when averaged over the 18 sessions or during session blocks (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

MT1/MT2-null effects on choice accuracy in male and female mice across training. Male MT1/MT2-null mice (solid bars) showed significant impairment relative to male wild-type (open bars) mice during the mid and late phases of training. Entries to repeat (mean±sem)

Mercury had an effect on choice accuracy as a part of an interaction with genotype and session block (F(4,282)=2.09, p<0.09). The mercury × genotype × session block three-way interaction was followed by tests of the simple main effects of mercury exposure with genotype. As shown in Figure 2, postnatal mercury exposure (5 mg/kg) caused a significant choice accuracy impairment in the MT1/MT2-null group during the initial phase of training (F(1,141)=6.38, p<0.025). This impairment was not seen when comparing mercury (5 mg/kg) and vehicle exposed wild-type mice. The comparison between wild-type and MT1/MT2-null mice treated with 5 mg/kg of mercury was also significant (F(1,141)=5.06, p<0.05). There was also evidence of mercury-induced impairment during the middle phase of training (sessions 7–12). Mercury exposure (2 mg/kg) caused significant impairment in MT1/MT2-null mice relative to vehicle treated MT1/MT2-null controls (F(1,141)=3.91, p<0.05). No significant mercury induced impairment was in the last training session (13–18).

Figure 2.

Postnatal mercury effects of spatial discrimination on the radial-arm maze in wild-type (open bars) and MT1/MT2-null (solid bars) mice. Mercury exposure caused learning defects in the early sessions of radial-arm maze acquisition training (mean±sem).

There were no signs of mercury-induced impairment in the wild-type mice at the doses tested. In fact the low dose (2 mg/kg) of mercury caused a significant improvement in choice accuracy during the initial training phase (F(1,141)=6.47, p<0.025; Fig 2). Mercury treatment did not appear to have differential effects in males and females. There was a significant (F(2,282)=84.86, p<0.0001) improvement of accuracy regardless of genotype, mercury treatment and sex.

With respect to latency responses in the radial-arm maze, there was a significant genotype × session block interaction (F(2,282)=14.14, p<0.0001). The simple main effects tests of the genotype at each session block showed that the MT1/MT2-null mice were significantly slower during training session 1–6 (F(1,141)=9.52, p<0.005). Wild-type mice averaged 25.6±1.5 seconds per entry while MT1/MT2-null animals averaged 35.1±2.9 seconds per entry (data not shown). During the middle phase of training (sessions 7–12) the MT1/MT2-null mice sped up to be significantly (F(1,141)=6.75, p<0.025) faster (22.3±0.9 seconds per entry) than wild-type mice (26.5±1.3 seconds per entry; data not shown). With respect to mercury exposure there was a three-way interaction of Mercury × Sex × session block (F(4,282)=2.07, p<0.09). This was followed up with tests of the simple main effects of mercury treatment in males and females during each session block. The only significant (F(1,141)=6.19, p<0.025) effect seen was a significant speeding in response in females in the 2 mg/kg mercury group (24.0±1.4 seconds per entry) vs untreated female mice (30.6±1.9 seconds per entry) during the middle training phase (sessions 7–12).

Neurochemical Analyses

Dopamine and serotonin are important for the processes of learning and memory. Mercury exposure can have differential effects on the concentration of these monoamines. Thus we decided to determine if the interactive effects of mercury × genotype in the early phases of acquisition or the effects of genotype in the later phases could be correlated to neurochemical changes.

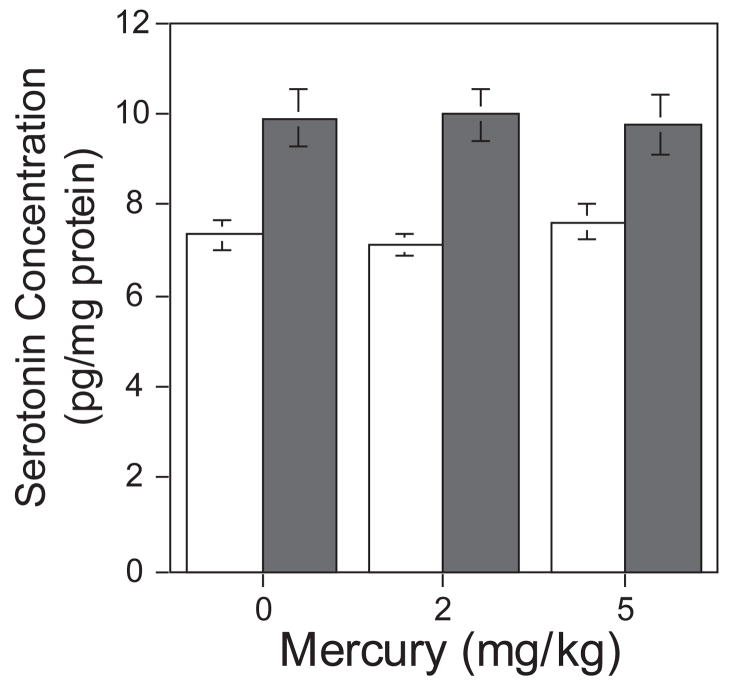

MT1/MT2-null mice had a substantial increase in the levels of serotonin in the frontal cortex relative to wild-type mice (36%) (F(1,130)=45.90, p<0.0001; Fig 3). There was an interaction of genotype × sex (F(1,130)=2.81, p<0.10) which was followed-up with tests of the genotype in males and females. The increase in frontal serotonin was more pronounced when comparing wild-type and MT1/MT2-null males (F(1,130)=36.94, p<0.0001; not shown). There was also a significant increase when comparing wild-type and MT1/MT2-null females (F(1,130)=12.58, p<0.0005; not shown). Mercury exposure did not have an effect on frontal cortical serotonin or 5-HIAA levels in wild-type or MT1/MT2-null mice (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Mercury exposure and MT1/MT2-null effects on serotonin levels in the frontal cortex (mean±sem). Serotonin levels were significantly higher in MT1/MT2-null mice (solid bars) compared to wild-type mice (open bars) (p<0.0001). Frontal cortical serotonin levels were not affected by prenatal mercury exposure in wild-type or MT1/MT2-null mice.

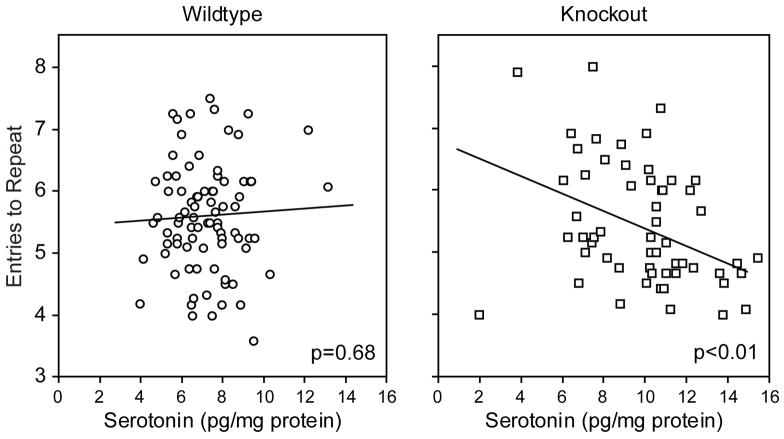

The substantial effect of MT1/MT2-null genotype on frontal serotonin levels may be related to the spatial learning and memory deficits they show. As shown in figure 4 a regression analysis revealed a significant correlation between choice accuracy in session 7–18 and serotonin levels in male MT1/MT2-null mice (p<0.01). This correlation was not seen in wild-type male mice (p=0.68).

Figure 4.

Regression analysis of the relationship of choice accuracy (entries to repeat mean±sem) in wildtype and MT1/MT2-null mice during mid and late phases of training (sessions 7–12).

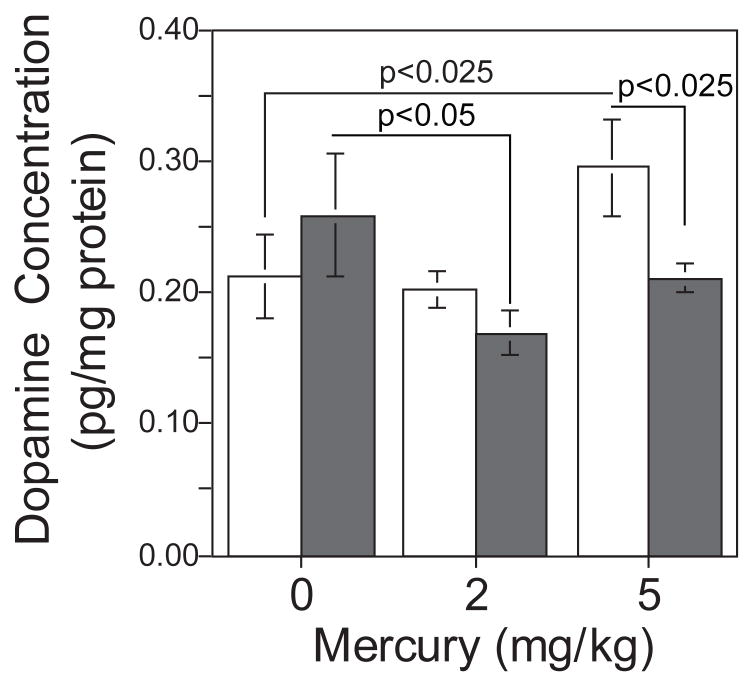

There was not a main effect of MT1/MT2-null genotype on frontal dopamine levels (Fig 5). However there was a differential effect of developmental mercury exposure on frontal dopamine levels in MT1/MT2-null and wild-type mice. The 5 mg/kg mercury dose caused a significant increase in frontal dopamine levels in the wild-type mice (F(1,130)=6.63, p<0.025). No such mercury-induced increase was seen in the MT1/MT2-null mice. In fact, there was a significant decrease in frontal dopamine in MT1/MT2-null mice exposed to 2 mg/kg of mercury (F(1,130)=4.75, p<0.05). At the highest dose (5 mg/kg) there was a general trend toward lower dopamine levels. There was also a significant difference in frontal dopamine levels between mercury exposed (5 mg/kg) wild-type and MT1/MT2-null mice (F(1,130)=5.74, p<0.025).

Figure 5.

Mercury exposure and metallothionein null effects on dopamine levels in the frontal cortex (mean±sem). Mercury exposure caused a significant increase in frontal cortical dopamine levels of wild-type mice (open bars) but not MT1/MT2-null mice (solid bars); main effect of genotype p<0.05. There was a significant difference in dopamine levels of wild-type and MT1/MT2-null mice exposed to mercury.

The mercury-induced increase in frontal dopamine levels in wild-type may be relevant to the protection against memory impairment. MT1/MT2-null mice which do not show this mercury-induced dopamine effect had significant learning deficits in the initial training sessions (1–6; Fig 2).

Discussion

The data shown here supports our previous findings that deletion of the MT1 and MT2 genes is associated with learning impairment of young adult and aging mice. In both studies this effect emerged during mid to late phases of training on the radial–arm maze [26]. Expanding on these findings, the current study demonstrated that HgCl2 exposure (5 mg/kg) caused significant choice accuracy impairment in MT1/MT2-null mice compared to vehicle-treated MT1/MT2-null controls, as well as mercury-exposed wild-type mice (Fig 2). However mercury-induced cognitive impairment was limited to the earlier phases of maze acquisition. The mercury-exposed MT1/MT2-null mice were eventually able to learn the task, but they took longer to do so. This supports our hypothesis that the MT1/MT2 knockout mice would be more vulnerable to the persisting cognitive impairment caused by developmental mercury exposure.

In the current study we tested the cognitive effect of neonatal mercury exposure long after treatment (12 weeks). Surprisingly, MT1/MT2-null mice exhibited significant cognitive impairment long after mercury exposure. Other studies have also evaluated the effects of mercury exposure on cognitive outcomes long after exposure [32,48,49]. MT1/MT2-null mice exposed to mercury vapor show both short term and long-term defects in locomotor activity in the open field maze [48]. However the effects of mercury vapor exposure on spatial learning were only seen immediately after cessation of dosing and not 12 weeks after exposure. Prenatal mercury exposure on the other hand induces long-term effects on locomotion and spatial learning [49]. In our study subcutaneous mercury exposure induced cognitive impairment that was measurable at the 12 week time period. It is possible that the route of mercury administration (i.e. inhalation, prenatal, subcutaneous injection) greatly effects cognitive outcome via the accumulation of mercury in the nervous system [48,49]. However further studies are needed to evaluate this possibility in subcutaneous injected mice in that we do not have measures of brain mercury levels to compare to published results. Another significant difference between the studies is the testing protocol used to evaluate spatial learning. Yoshida et al used the Morris water maze to evaluate spatial learning while we utilized the 8-arm radial maze.

With respect to brain mercury concentrations, Peixoto et al. [32] showed that mercury levels remain elevated when rats are exposed during postnatal days 1–5 and 8–12 but not when exposed during later time points [32]. In fact there was a significant effect of early (1–5) exposure and increased sensitivity to mercury exposure. This time period is well within the time range of our exposures.

Working memory has been shown to be highly reliant on mesocortical dopamine neurotransmission. Studies in both rodents and non-human primates have shown a correlation between neuronal activity in the prefrontal cortex and the accuracy of working memory [11,12,35]. Dopamine efflux in the prefrontal cortex of non-human primates is associated with accuracy in a delayed alternation task [46]. The magnitude of dopamine release in the PFC also predicts memory accuracy in rats [34,38]. In contrast to dopamine, very little is known regarding that correlation between serotonin levels in the prefrontal cortex and working memory. However the prefrontal cortex receives extensive serotonergic innervation and expresses high levels of 5HT receptors [13,22]. Studies have also shown that depletion of serotonin via i.c.v injection of 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine impairs working memory [19].

Dopamine levels in the frontal cortex of wildtype mice were significantly increased by developmental mercury exposure (5 mg/kg). MT1/MT2-null mice did not show this effect. In fact MT1/MT2-null mice showed a general trend toward lower cortical dopamine levels with mercury exposure. Other studies have reported that wild-type mice respond to developmental mercury exposure by increasing dopamine concentrations. Faro and colleagues found a correlation between postnatal organic and inorganic mercury exposure and increased dopamine levels in the striatum [7–9]. The increase in frontal dopamine in the wild-type mice may help protect them against mercury-induced impairment. In support of this hypothesis, MT1/MT2-null mice (which exhibited significant cognitive impairment) did not respond to mercury exposure by elevating frontal dopamine concentrations. The differences in frontal dopamine levels were specific to differential response to developmental mercury exposure in that there were no differences in mean dopamine levels between untreated wild-type and MT1/MT2-null mice.

Serotonin levels were higher in the frontal cortex of untreated MT1/MT2-null mice compare to untreated, wild-type mice. Mercury exposure was not found to affect serotonin levels in either wild-type or MT1/MT2-null mice. The disrupted serotonin systems in MT1/MT2-null may be related to the cognitive impairment that they show during the mid to late phases of radial-arm maze learning. Human studies have shown that altered serotonin regulation can be associated with significant impairments in learning and memory [44]. However an alternative explanation could account for cognitive impairment in MT1/MT2-null. Cognitive impairment in MT1/MT2-null mice may be related to elevated serotonin and altered fear and stress responses.

The involvement of serotonin in stress and anxiety is well documented [15]. Several studies have demonstrated that stress in various animal models of anxiety is related to increased serotonin release in the brain [29,36,39,43,47]. Stress induced by physical restraint also increases serotonin in the cerebral cortex and hypothalamus [6]. These studies support the possibility that 8-arm radial maze impairment in MT1/MT2-null mice may be related to stress mediated responses. To further support this interpretation, increased latency responses in the MT1/MT2-null mice occurred in the same sessions where we observed alterations in arm radial maze performance (session 1–6). Typically, increased latency in the radial arm maze relates to either locomotion defects or increased stress in navigating the elevated arms of the maze. So far data in MT1/MT2-null mice has not distinguished these two possibilities. In the absence of mercury MT1/MT2-null mice do not show locomotor defects in the open field maze [48,49]. Mercury exposure causes both hyper-and hypo-activity in 12 week MT1/MT2-null mice [48,49]. This raises the possibility that mercury induced locomotor defects in MT1/MT2-null mice involve of fear and stress responses.

However as it relates to this interpretation (that increased stress causes choice accuracy impairment), there was significant cognitive impairment in the later phases of maze testing in MT1/MT2-null male mice even though there were no longer any significant differences in latency times (Fig 1 and data not shown). This supports a model whereby serotonin directly mediates cognitive impairment independent of stress in the later phases of the task.

The MT × Hg interaction seen during the initial phase of testing may be related to fear and stress responses. Several models of acute stress in rodents have shown that one mechanism by which rodents respond to stress is by up-regulating the expression of metallothioneins [5]. However this adaptive mechanism for handling stress in absent in the MT1/MT2-null mice. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis and to evaluate the interactive effects of stress, serotonin, and metallothioneins.

The current study investigated the effect of metallic mercury exposure on cognitive outcome in MT1/MT2-null mice in a 129 background. It has been demonstrated that 129/SvJ (129) mice are more susceptible to environmental toxicant exposure. Liu et al. [27] report that 129 mice have increased sensitive to cadmium induced testicular damage compared to C57BL/6J (C57) mice [27]. It is important to note that the effects of cadmium exposure are not dependent on the expression of MT1/MT2. MT1/MT2-null and 129 mice are equally sensitive to cadmium induce testicular atrophy. Additionally, atrophy in both mouse lines is significantly different from that of C57 mice [27]. However, Satoh reports that MT1/MT2-null mice in a C57 background are sensitive to cadmium and mercury toxicity [40]. There was also an increased sensitivity to arsenic, oxidative stress, and chemical carcinogenesis in C57 MT1/MT2-null mice [40]. Additionally, mercury and thimerosal exposure induces autoimmune responses in genetically susceptible mice [17,20,45]. Mercury induced autoimmunity is regulated in part by major histocompatibility complex (MHG) genes [1,21]. Hornig et al. investigating the role of strain dependent autoimmunity on neuropathic disturbances found that autoimmune disease-sensitive SJL/J mice, but not C57 or BALB mice, were susceptible to the neurotoxic effects of postnatal thimerosal exposure [18]. Specifically, SJL/J mice showed growth delay, reduced locomotion, exaggerated response to novelty, and anatomical changes in the hippocampus [18]. These studies highlight the limitations of using the 129 background to study mercury induced cognitive impairment. However studies investigating the link between thimerosal exposure, metallothionein heterogeneity, and cognitive impairment in autism spectrum disorders have been inconclusive. This raises the possibility that there may be an interactive effect of mercury toxicity, metallothionein heterogeneity, and autoimmune subseptiblity in neurodevelopment and neurocognitive outcomes.

The current study demonstrates that deletion of metallothionein genes potentates learning impairments caused by postnatal mercury exposure. The MT1/MT2-null mouse provides a model for the adverse effects associated with the disruption of normal transition metal metabolism. Determining the roles of metallothionein in neurocognitive function can aid not only in basic understanding of the roles of transition metals in the neural basis of cognition, but also help in the analysis of the neural mechanisms underlying cognitive impairment such as is seen in metal intoxication. Furthermore, the MT1/MT2-null mouse may provide a forum for understanding the consequences of disrupting normal transition metal metabolism on neurodevelopment, learning, and behavior. It may also provide mechanistic information concerning the causes and treatments of cognitive impairments caused by developmental exposure to toxic metals.

TABLE 1.

Animal sample size used to evaluate mercury-induced behavioral defects and monoamine levels in the frontal cortical of mercury exposed MT1/MT2-null and wild-type mice

| Behavior | Neurochemistry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury Dose (mg/kg) | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wild-type | ||||||

| Males | 15 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 14 |

| Females | 14 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 16 | 16 |

|

| ||||||

| MT1/MT2-null | ||||||

| Males | 11 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| Females | 11 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

Acknowledgments

Research support was provided by grants from the National Association for the Advancement of Autism Research, Autism Speaks and the Duke University Superfund Basic Research Center (ES010356).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abedi-Valugerdi M, Nilsson C, Zargari A, Gharibdoost F, DePierre JW, Hassan M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide both renders resistant mice susceptible to mercury-induced autoimmunity and exacerbates such autoimmunity in susceptible mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:238–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard S, Enayati A, Redwood L, Roger H, Binstock T. Autism: a novel form of mercury poisoning. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56:462–71. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard S, Enayati A, Roger H, Binstock T, Redwood L. The role of mercury in the pathogenesis of autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(Suppl 2):S42–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrasco J, Penkowa M, Hadberg H, Molinero A, Hidalgo J. Enhanced seizures and hippocampal neurodegeneration following kainic acid-induced seizures in metallothionein-I + II-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2311–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen WQ, Cheng YY, Zhao XL, Li ST, Hou Y, Hong Y. Effects of zinc on the induction of metallothionein isoforms in hippocampus in stress rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1564–8. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Souza EB, Van Loon GR. Brain serotonin and catecholamine responses to repeated stress in rats. Brain Res. 1986;367:77–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faro LR, do Nascimento JL, Alfonso M, Duran R. In vivo effects of inorganic mercury (HgCl(2)) on striatal dopaminergic system. Ecotoxicology & Environmental Safety. 2001;48:263–7. doi: 10.1006/eesa.2000.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faro LR, do Nascimento JL, San Jose JM, Alfonso M, Duran R. Intrastriatal administration of methylmercury increases in vivo dopamine release. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:225–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1007571403413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faro LR, Duran R, do Nascimento JL, Alfonso M, Picanco-Diniz CW. Effects of methyl mercury on the in vivo release of dopamine and its acidic metabolites DOPAC and HVA from striatum of rats. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1997;38:95–8. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1997.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giralt M, Penkowa M, Lago N, Molinero A, Hidalgo J. Metallothionein-1+2 protect the CNS after a focal brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2002;173:114–28. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman-Rakic PS. Working memory and the mind. Sci Am. 1992;267:110–7. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0992-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron. 1995;14:477–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman-Rakic PS. Regional and cellular fractionation of working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13473–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goulet S, Dore FY, Mirault ME. Neurobehavioral changes in mice chronically exposed to methylmercury during fetal and early postnatal development. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:335–47. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griebel G. 5-Hydroxytryptamine-interacting drugs in animal models of anxiety disorders: more than 30 years of research. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;65:319–95. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)98597-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamer DH. Metallothionein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:913–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.004405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havarinasab S, Lambertsson L, Qvarnstrom J, Hultman P. Dose-response study of thimerosal-induced murine systemic autoimmunity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornig M, Chian D, Lipkin WI. Neurotoxic effects of postnatal thimerosal are mouse strain dependent. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:833–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hritcu L, Clicinschi M, Nabeshima T. Brain serotonin depletion impairs short-term memory, but not long-term memory in rats. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hultman P, Enestrom S. Dose-response studies in murine mercury-induced autoimmunity and immune-complex disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;113:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hultman P, Hansson-Georgiadis H. Methyl mercury-induced autoimmunity in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;154:203–11. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jakab RL, Goldman-Rakic PS. Segregation of serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptors in inhibitory circuits of the primate cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2000;417:337–48. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000214)417:3<337::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagi JH, Schaffer A. Biochemistry of metallothionein. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8509–15. doi: 10.1021/bi00423a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly EJ, Quaife CJ, Froelick GJ, Palmiter RD. Metallothionein I and II protect against zinc deficiency and zinc toxicity in mice. J Nutr. 1996;126:1782–90. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.7.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazo JS, Kondo Y, Dellapiazza D, Michalska AE, Choo KH, Pitt BR. Enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress in cultured embryonic cells from transgenic mice deficient in metallothionein I and II genes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5506–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin ED, Perraut C, Pollard N, Freedman JH. Metallothionein expression and neurocognitive function in mice. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Corton C, Dix DJ, Liu Y, Waalkes MP, Klaassen CD. Genetic background but not metallothionein phenotype dictates sensitivity to cadmium-induced testicular injury in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;176:1–9. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masters BA, Kelly EJ, Quaife CJ, Brinster RL, Palmiter RD. Targeted disruption of metallothionein I and II genes increases sensitivity to cadmium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:584–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuo M, Kataoka Y, Mataki S, Kato Y, Oi K. Conflict situation increases serotonin release in rat dorsal hippocampus: in vivo study with microdialysis and Vogel test. Neurosci Lett. 1996;215:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12982-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielson KB, Atkin CL, Winge DR. Distinct metal-binding configurations in metallothionein. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5342–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park JD, Liu Y, Klaassen CD. Protective effect of metallothionein against the toxicity of cadmium and other metals(1) Toxicology. 2001;163:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peixoto NC, Roza T, Morsch VM, Pereira ME. Behavioral alterations induced by HgCl2 depend on the postnatal period of exposure. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penkowa M, Giralt M, Camats J, Hidalgo J. Metallothionein 1+2 protect the CNS during neuroglial degeneration induced by 6-aminonicotinamide. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:174–89. doi: 10.1002/cne.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips AG, Ahn S, Floresco SB. Magnitude of dopamine release in medial prefrontal cortex predicts accuracy of memory on a delayed response task. J Neurosci. 2004;24:547–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4653-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt WE, Mizumori SJ. Neurons in rat medial prefrontal cortex show anticipatory rate changes to predictable differential rewards in a spatial memory task. Behav Brain Res. 2001;123:165–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rex A, Marsden CA, Fink H. Effect of diazepam on cortical 5-HT release and behaviour in the guinea-pig on exposure to the elevated plus maze. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110:490–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02244657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rofe AM, Philcox JC, Coyle P. Trace metal, acute phase and metabolic response to endotoxin in metallothionein-null mice. Biochem J. 1996;314(Pt 3):793–7. doi: 10.1042/bj3140793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossetti ZL, Carboni S. Noradrenaline and dopamine elevations in the rat prefrontal cortex in spatial working memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2322–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3038-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rueter LE, Jacobs BL. A microdialysis examination of serotonin release in the rat forebrain induced by behavioral/environmental manipulations. Brain Res. 1996;739:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satoh M. Analysis of toxicity using metallothionein knockout mice. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2007;127:709–17. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.127.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Iowa State University Press; Ames, Iowa: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stennard FA, Holloway AF, Hamilton J, West AK. Characterisation of six additional human metallothionein genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:357–65. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Storey JD, Robertson DA, Beattie JE, Reid IC, Mitchell SN, Balfour DJ. Behavioural and neurochemical responses evoked by repeated exposure to an elevated open platform. Behav Brain Res. 2006;166:220–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verkes RJ, Gijsman HJ, Pieters MS, Schoemaker RC, de Visser S, Kuijpers M, Pennings EJ, de Bruin D, Van de Wijngaart G, Van Gerven JM, Cohen AF. Cognitive performance and serotonergic function in users of ecstasy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;153:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s002130000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warfvinge K, Hansson H, Hultman P. Systemic autoimmunity due to mercury vapor exposure in genetically susceptible mice: dose-response studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;132:299–309. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe M, Kodama T, Hikosaka K. Increase of extracellular dopamine in primate prefrontal cortex during a working memory task. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2795–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright IK, Upton N, Marsden CA. Effect of established and putative anxiolytics on extracellular 5-HT and 5-HIAA in the ventral hippocampus of rats during behaviour on the elevated X-maze. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;109:338–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02245882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida M, Watanabe C, Horie K, Satoh M, Sawada M, Shimada A. Neurobehavioral changes in metallothionein-null mice prenatally exposed to mercury vapor. Toxicol Lett. 2005;155:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida M, Watanabe C, Kishimoto M, Yasutake A, Satoh M, Sawada M, Akama Y. Behavioral changes in metallothionein-null mice after the cessation of long-term, low-level exposure to mercury vapor. Toxicol Lett. 2006;161:210–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]