Abstract

Aim

While clinical endpoints provide important information on the efficacy of treatment in controlled conditions, they often are not relevant to decision makers trying to gauge the potential economic impact or value of new treatments. Therefore, it is often necessary to translate changes in cognition, function or behavior into changes in cost or other measures, which can be problematic if not conducted in a transparent manner. The Dependence Scale (DS), which measures the level of assistance a patient requires due to AD-related deficits, may provide a useful measure of the impact of AD progression in a way that is relevant to patients, providers and payers, by linking clinical endpoints to estimates of cost effectiveness or value. The aim of this analysis was to test the association of the DS to clinical endpoints and AD-related costs.

Method

The relationship between DS score and other endpoints was explored using the Predictors Study, a large, multi-center cohort of patients with probable AD followed annually for four years. Enrollment required a modified Mini-Mental State Examination (mMMS) score ≥30, equivalent to a score of approximately ≥16 on the MMSE. DS summated scores (range: 0–15) were compared to measures of cognition (MMSE), function (Blessed Dementia Rating Scale, BDRS, 0–17), behavior, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), and psychotic symptoms (illusions, delusions or hallucinations). Also, estimates for total cost (sum of direct medical cost, direct non-medical cost, and cost of informal caregivers’ time) were compared to DS scores.

Results

For the 172 patients in the analysis, mean baseline scores were: DS: 5.2 (SD: 2.0), MMSE: 23.0 (SD: 3.5), BDRS: 2.9 (SD: 1.3), EPS: 10.8%, behavior: 28.9% psychotic symptoms: 21.1%. After 4 years, mean scores were: DS: 8.9 (SD: 2.9), MMSE: 17.2 (SD: 4.7), BDRS: 5.2 (SD: 1.4), EPS: 37.5%, behavior: 60.0%, psychotic symptoms: 46.7%. At baseline, DS scores were significantly correlated with MMSE (r=−0.299, p<0.01), BDRS (r=0.610, p<0.01), behavior (r=.2633, p=0.0005), EPS (r=0.1910, p=0.0137) and psychotic symptoms (r=0.253, p<0.01); and at 4-year follow-up, DS scores were significantly correlated with MMSE (r=−0.3705, p=0.017), BDRS (r=0.6982, p<0.001). Correlations between DS and behavior (−0.0085, p=0.96), EPS (r=0.3824, p=0.0794), psychotic symptoms (r=0.130, ns) were not statistically significant at follow-up. DS scores were also significantly correlated with total costs at baseline (r=0.2615, p=0.0003) and follow-up (r=0.3359, p=0.0318).

Discussion

AD is associated with deficits in cognition, function and behavior, thus it is imperative that these constructs are assessed in trials of AD treatment. However, assessing multiple endpoints can lead to confusion for decision makers if treatments do not impact all endpoints similarly, especially if the measures are not used typically in practice. One potential method for translating these deficits into a more meaningful outcome would be to identify a separate construct, one that takes a broader view of the overall impact of the disease. Patient dependence, as measured by the DS, would appear to be a reasonable choice – it is associated with the three clinical endpoints, as well as measures of cost (medical and informal), thereby providing a bridge between measures of clinical efficacy and value in a single, transparent measure.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by impairment in cognition, function, and behavior. As disease progresses over time, these impairments translate into increased patient dependence on others, resulting in higher need for informal (unpaid) care from family and friends, formal (paid) care, and medical care. Existing research of AD treatments has typically focused on separate measures of cognition and function as discrete, specific clinical trial endpoints, with behavioral impacts treated separately as secondary or exploratory endpoints. Conversely, global measures such as the clinical impression of change have been utilized to determine the overall impact of the disease, though these measures do not provide any granularity regarding level of impact or change over time.

An alternative method is to try to take a broader view that incorporates as many of these discrete clinical endpoints possible. While clinical trial endpoints provide important information on the efficacy of AD treatments, they may not be relevant to decision makers trying to gauge the impact of the disease and/or the value of treatments. Assessing multiple trial endpoints also can lead to confusion for decision makers if treatments do not impact all endpoints similarly, especially if the measures are typically not used in clinical practice. Measures that link trial endpoints to clinically and patient relevant measures could provide more transparency and inform decision making for patients, their families, healthcare providers and payers.

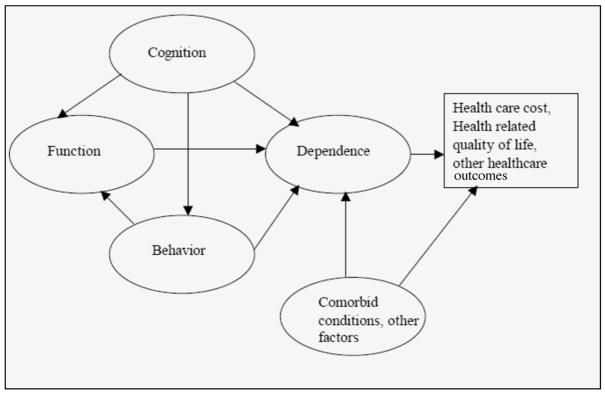

One potential method for translating these multiple trial endpoints into a more meaningful outcome would be to identify a separate construct, one that takes a broader view of the overall impact of the disease, but also provide granularity regarding level of impact or change over time. Recently, the concept of dependence began to receive attention from the research community (1). To this end, the Dependence Scale (DS) was developed to directly measure the amount of assistance AD patients need due to impairments in cognition, function and behavior (2). The relationship between dependence and specific clinical endpoints such as cognition, function, and behavior, and the translation of these clinical endpoints into health and economic outcomes via dependence are conceptualized in Figure 1. Impairments in cognition contribute to AD patients’ increased dependence on others, either directly (for example, need for reminders of person, place or time), or indirectly through functional impairments. Similarly, functional impairments may directly translate to increased dependence (loss of activities of daily living means a patient needs more assistance in these activities), and behavioral problems may lead to increased supervisory needs. As the trajectory of changes in these constructs may differ across patients and/or time, translating their impact into a concept such as dependence could allow for better characterization of the overall impact of these varying impairments as they relate to economic outcomes such as resource utilization and cost; as well as impacts on health related quality of life (HRQOL). Research into the content of the DS shows that the DS measures related but distinct aspects of disability in AD and that the concept resonates with reports from both patients and caregivers on the impact of the disease (3, 4).

Figure 1.

Translating Clinical Endpoints into Health Outcomes via Dependence

While impairments in cognition, function and behavior would be expected to explain much of the variation in an AD patient’s dependence level, it is likely that other aspects (e.g., comorbid conditions) would also play a part not only in explaining dependence, but also in relating to economic and humanistic outcomes.

In this report we examine empirically the relationship between patients’ DS scores and clinical endpoints (cognition, function, behavior) and economic endpoints (direct medical, direct non-medical, informal care costs). We compare the strengths of the relationships with different endpoints. Results reported here are summarized from earlier studies (5).

The sample used for this report is drawn from the Predictors II cohort. Patients who were mildly demented were recruited from three University-based AD centers in the US and followed every 6 months, with annual assessment in economic outcomes. All subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer type and NINDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD. Enrollment required a modified Mini-Mental State examination (mMMS) score ≥30, equivalent to a score of approximately ≥16 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The analysis data includes patients who were followed up to 4 years. The typical patient in the analysis sample was female (58%), 76 years old, white, and had over 14 years of education. At baseline, average DS score was 5.2 (sd=2.2), indicating a mild level of dependence, with average MMSE at 22.1 (sd=3.6) and average BDRS score at 3.5 (sd=2.1). Behavioral problems (41.6%) were common. About a third (30.2%) had psychotic symptoms, 20.5% had depressive symptoms, and 14.5% had extrapyramidal signs (EPS). On average, patients had fewer than one comorbid condition (mean=0.8, sd=0.9); almost half of the patients (47.8%) did not have any comorbid conditions.

Dependence Scale

The Dependence Scale (DS) consists of 13 items, representing a wide range of levels of care required by a patient, from relatively subtle items such as needing reminders or advice to more gross forms such as needing to be fed (2). All items deal with patients’ needs. In some cases, the need is only for supervision, without any specific tasks linked to the need. The instrument is designed to be administered to a reliable informant who lives with the patient or one who is well informed about the patient’s daily activities and needs. With the exception of the first two items (needs reminders to manage chores, needs help to remember important things such as appointments) which are coded as 0 (no), 1 (occasionally, at least once a month), and 2 (frequently, at least once a week), responses to the rest of the items are coded dichotomously and indicate whether the patient requires assistance in a particular item (0=no, 1=yes). The total DS score is the sum of scores on all 13 items (range=0–15), and provides a continuous index of progressively greater dependence on others. Table 1 details the questions in the Dependence Scale.

Table 1.

The Dependence Scale Questionnaire

|

Items A and B are coded as follows: no, 0; occasionally (ie, at least once a month), 1; frequently (ie, at least once a week), 2. The other items are coded as follows: no, 0; yes, 1. Total Dependence Scale score is the sum of scores on all 13 items (range=0–15).

Clinical Endpoints

We assessed the relationship between DS and the following clinical endpoints: (1) Patients’ cognitive limitation was measured by MMSE; (2) Functional impairment was measured by the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (BDRS) Parts I (Instrumental Activities of Daily living, IADLs) and II (Basic Activities of Daily living, BADLs); (3) Patients’ psychotic, behavioral, and depressive symptoms were measured by the Columbia University Scale for Psychopathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (CUSPAD), a semi-structured interview administered by a physician or a trained research technician; and (4) Patients’ extrapyramidal signs (EPS) were measured by the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). At baseline, total DS scores were significantly correlated with MMSE (r=−0.299, p<0.01), BDRS (r=0.610, p<0.01), behavior (r=.2633, p=0.0005), EPS (r=0.1910, p=0.0137) and psychotic symptoms (r=0.253, p<0.01); and at 4-year follow-up, DS scores were significantly correlated with MMSE (r=−0.3705, p=0.017), BDRS (r=0.6982, p<0.001). Correlations between DS and behavior (−0.0085, p=0.96), EPS (r=0.3824, p=0.0794), psychotic symptoms (r=0.130, ns) were not statistically significant at follow-up.

Economic Endpoints

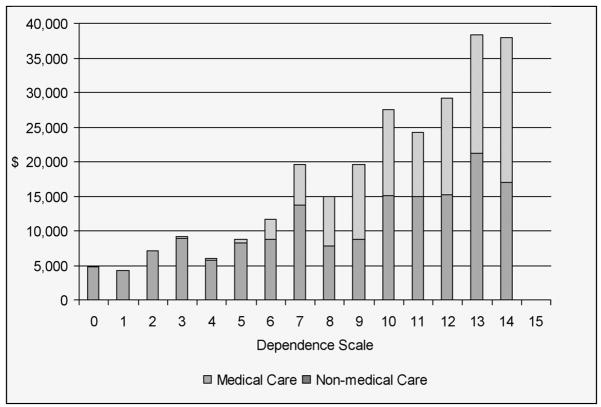

We took the perspective of the society and examined three economic endpoints, including direct medical care, direct non-medical care, and informal care. All resources used by the patient and caregiver were reported. Direct medical care included hospitalization, outpatient treatment/procedures, assistive devices, and medications. Direct non-medical care included care provided by home health aides, respite care, and adult daycare. Informal care was measured by up to three informal caregivers’ time for basic and instrumental activities of daily living. At baseline, total DS scores were significantly correlated with total costs (r=0.2615, p=0.0003), direct non-medical cost (r=0.30212, p<0.0001), informal hours per week (r=0.26019, p=0.0008); and at 4-year follow-up, DS scores were significantly correlated with total costs (r=0.3359, p=0.0318), direct non-medical cost (r=0.35728, p=0.0035), and informal hours per week (r=0.30700, p=0.0122). Figure 2 presents data on the relationship between total DS score and direct medical and non-medical costs.

Figure 2.

Medical and non-medical cost by dependence scale

Clinical and Policy Implications

AD is associated with impairments in cognition, function and behavior, thus it is important that these constructs are assessed in trials of AD treatment. However, if treatments do not impact all trial endpoints similarly, assessing multiple endpoints can lead to confusion for decision makers, including patients’ families, healthcare providers, and payers. This is especially problematic if the measures used in clinical trials are typically not used in clinical practice. One potential method for translating these AD related impairments into a more meaningful outcome would be to identify a construct that takes a broader view of the overall impact of the disease, and that takes into account differences in the trajectory of changes in these multiple constructs that differ across patients and/or time. In this paper we summarize evidence that patient dependence, as measured by the Dependence Scale, provides a potentially useful method for translating clinical results into meaningful outcomes. Results show that the Dependence Scale scores correlate well with measures of cognition and function as well as economic endpoints. Relationship observed at baseline is consistent over time, supporting its use for longitudinal studies.

The lack of correlation between DS and patients’ psychotic, behavioral, and depressive symptoms at year 4 merits discussion. We believe these results may be due to the roughness of the measures used in this study. For example, subcategories of extrapyramidal and psychotic symptoms were grouped together and we only used dichotomous gradations of severity. Additionally, behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in AD fluctuate over time. Particular symptoms can occur any time during the course of AD; Persistence of these symptoms also differs from symptom to symptom. The fact that medications also can be effective in managing patients’ psychotic, behavioral, and depressive symptoms may further lead to fluctuation in these symptoms from visit to visit.

Previous attempts to find a meaningful outcome with relevant impact in the progression of dementia focused mostly on the use of nursing home placement. The decision to institutionalize a patient is influenced by many non-medical factors such as existence of living family members, willingness and ability of the family to provide care, geographic location of family, financial and insurance status, and cultural beliefs. Thus, while clearly relevant and meaningful from an economic and humanistic standpoint, actual nursing home placement may not always be a good proxy for a patient’s true level of dependence or need for care. Unlike nursing home placement, patients’ dependence, as measured by the Dependence Scale, documents levels of needs directly and is independent of the caregiving site or setting. In addition to be well-correlated with clinical endpoints and measures of healthcare cost, the Dependence Scale also describes AD progression in terms that correspond with patient/caregiver perceptions of the impact of AD on their lives. Therefore, DS is potential method for translating multiple clinical endpoints into a more meaningful outcome that is more transparent to decision makers, including patients’ families, healthcare providers, and payers.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The Predictors Study is supported by Federal grants AG07370, RR00645, and U01AG010483. Funding for this analysis also was partially provided by Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Drs. Zhu and Sano also are supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors all certify that they have no relevant financial interests in this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work is from the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC) and Program of Research on Serious Physical and Mental Illness, Targeted Research Enhancement Program (TREP)

References

- 1.Jones RW, McCrone P, Guilhaume C. Cost effectiveness of memantine in Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis based on a probabilistic Markov model from a UK perspective. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:607–620. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern Y, Albert SM, Sano M, et al. Assessing patient dependence in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M216–222. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brickman AM, Riba A, Bell K, et al. Longitudinal assessment of patient dependence in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1304–1308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.8.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtzer R, Wegesin DJ, Albert SM, et al. The rate of cognitive decline and risk of reaching clinical milestones in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1137–1142. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu CW, Leibman C, McLaughlin T, et al. The Effects of Patient Function and Dependence on Costs of Care in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]