Abstract

A 41-yr-old man was admitted with acute headache, neck stiffness, and febrile sensation. Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed pleocytosis, an increased protein level and, a decreased glucose concentration. No organisms were observed on a culture study. An imaging study revealed pituitary macroadenoma with hemorrhage. On the 7th day of the attack, confusion, dysarthria, and right-sided facial paralysis and hemiparesis were noted. Cerebral infarction on the left basal ganglia was confirmed. Neurologic deficits gradually improved after removal of the tumor by endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal approach. It is likely that the pituitary apoplexy, aseptic chemical meningitis, and cerebral infarction are associated with each other. This rare case can serve as a prime example to clarify the chemical characteristics of pituitary apoplexy.

Keywords: Cerebral Infarction, Meningitis, Pituitary Apoplexy

INTRODUCTION

Pituitary apoplexy is a well-known clinical syndrome typically characterized by a sudden onset of headache, visual impairment, signs of meningeal irritation, disturbances of consciousness, and hormonal dysfunction. It is usually the result of hemorrhagic infarction associated with a pituitary adenoma or, occasionally, hemorrhage within a nonadenomatous tumor or a normal gland (1, 2). However, the actual presenting conditions may vary from asymptomatic hemorrhage (1, 3, 4), aseptic meningitis (5-8), vascular accident (9-12), subarachnoid hemorrhage (13, 14), massive hemorrhage (13), and even to sudden death (3).

The incidence of pituitary apoplexy ranges from 0.6% to 16.6% of pituitary adenomas according to its definition (3, 4). Asymptomatic hemorrhage or infarction accounts for 14 to 22% of pituitary tumors, while clinical apoplexy accounts for 0.6 to 9% (15). Although this wide range of incidence reflects the variable degree of severity or urgency in the presenting symptoms, the exact mechanisms of pituitary apoplexy and its subsequent presentation remain unknown.

In this report, a case of pituitary apoplexy complicated by aseptic chemical meningitis and cerebral infarction is described, and the feasible sequence of events is reviewed based on the available literature.

CASE REPORT

A 41-yr-old man was admitted following acute headache, vomiting, and retroorbital pain. He complained of intermittent headache and dizziness for 3 months. There was no remarkable past history of medico-surgical illness. Examination revealed fever (38.2℃) and neck stiffness, but no limitation of extraocular movement. He mentioned the sensation of visual blurring; however, vision had been preserved (visual acuity 1.0/0.8). Fundoscopy was normal, and visual fields were full. Lumbar puncture revealed xanthochromic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a pressure of 22 cmCSF; the CSF contained 239 mg/dL of protein and 12 mg/dL of glucose with 986 per µL white blood cell (polymorphs 97% and lymphocyte 3%) but no erythrocytes. No organisms were observed on a culture study. Upon computerized tomography (CT) scan with CT angiography, a pituitary mass with some suprasellar extension was identified, but no aneurysmal sac or definite evidence of hemorrhage in the subarachnoid space was detected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed a macroadenoma extending to the left cavernous sinus and suprasella with an intratumoral hemorrhage and cyst (Fig. 1). Thyroid, adrenocortical, or gonadal insufficiencies were not present. Headache and neck stiffness gradually improved over the next six days with conservative treatment with methylprednisolone and antibiotics. A follow-up CSF study also indicated improvement in meningitis: pressure 14 cmCSF, colorless, WBC 213 per µL (polymorphs 71% and lymphocyte 23%), protein 118 mg/dL, and glucose 44 mg/dL. On the 7th day of apoplexy, the patient complained of aggravated headache and exhibited intermittent confusion, dysarthria, and right-side facial paralysis and hemiparesis. Follow-up CT scan showed low density on the head of the caudate nucleus, the genu of the internal capsule, and the anterior portion of the putamen and globus pallidus on the left side. Diffusion-weighted image of the MRI scan showed a bright signal in the corresponding area (Fig. 2). The patient's neurologic deficits gradually improved, and subsequent images also indicated decreased size of infarction. The pituitary tumor was removed via endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal approach. The histology revealed a typical hemorrhagic infarction of pituitary adenoma compatible with pituitary apoplexy (Fig. 3). Postoperative panhypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus required hormonal replacement.

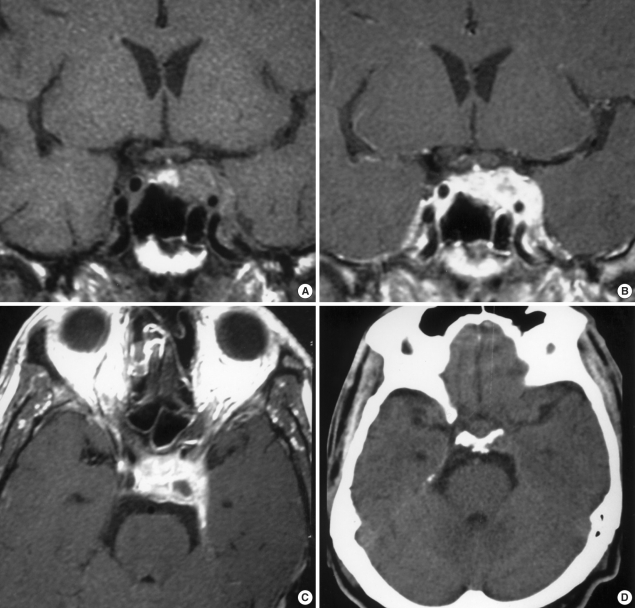

Fig. 1.

(A) T1-weighted non-enhanced coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a pituitary mass with increased focal signal intensity that reflects intratumoral hemorrhage. (B) T1-weighted enhanced coronal MRI shows strong enhancement of the pituitary tumor extending to the left cavernous sinus, but not compromising the optic chiasm. (C) Enhanced axial image of MRI shows a high signal intensity lesion and a small cystic area. (D) There is no hemorrhage in the subarachnoid space of the basal cistern on an initial computerized tomography scan.

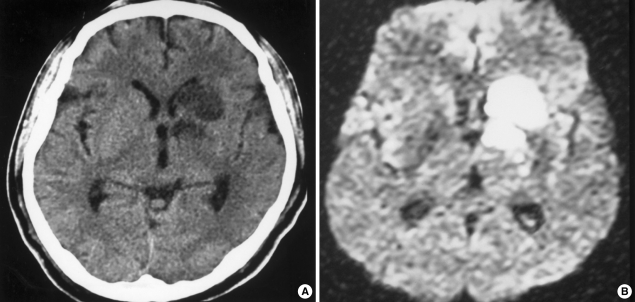

Fig. 2.

(A) On the 7th day of pituitary apoplexy, non-contrast computerized tomography scan shows low density on deep nuclei and internal capsule. (B) Diffusion-weighted image of magnetic resonance imaging scan reveals hyperintense infarction in the same area.

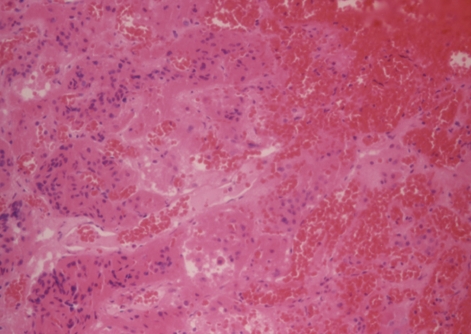

Fig. 3.

Histology of pituitary adenoma reveals hemorrhagic infarct with necrotic neoplastic cells and congested vessels supporting the diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy (H&E stain, ×200).

DISCUSSION

The meningeal irritation sign is a fairly common symptom of pituitary apoplexy with an incidence ranging from 16.7 to 85% (16, 17). These signs are caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage accompanied by pituitary apoplexy (3, 13, 16) or by sterile chemical meningitis (5-7). The reported series of chemical meningitis characterized by the state of acute headache, fever, and spinal pleocytosis were clinically indistinguishable from infectious meningitis. In fact, the possibility of infectious or tuberculous meningitis in the present patient was not clearly ruled out, nor were his visual symptoms urgent. As a result, tumor removal was delayed. Cerebral infarction contributed to the surgical delay as well. Following surgery, his visual symptoms were resolved completely. Considering the frequency of meningismus, sterile meningitis confirmed with CSF examination is not common. It is thought that chemical meningitis induced by pituitary apoplexy might be underestimated. The laboratory confirmation of meningitis is possible only with CSF examination. The abrupt onset of altered consciousness, visual loss, and ocular palsy that occur in pituitary apoplexy require urgent surgical decompression. Furthermore, the pituitary apoplexy in large-sized pituitary adenomas generally makes one reluctant to proceed with lumbar puncture. In addition, accurate, fast, noninvasive radiologic tools are available for diagnosing the patient's state.

The probable causes of the cerebral vasospasm related with pituitary adenomas are subarachnoid blood released from hemorrhagic, necrotic pituitary adenoma or from intraoperative spillage, direct arterial wall injury, hypothalamic damage, some chemical substances or mechanical compression by a tumor (9, 18). Cardoso et al. clearly demonstrated an example of vasospasm induced by subarachnoid hemorrhage liberated from pituitary apoplexy (19). They noticed a large amount of blood in the basal cisterns at the time of transcranial approach to remove a pituitary adenoma and reported marked spasm of both internal carotid arteries, as well as the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. There were also a few reports of cerebral vasospasm after surgery for pituitary macroadenoma without pituitary apoplexy (18, 20). These reports concluded that the most probable cause of vasospasm after transsphenoidal tumor removal was subarachnoid hematoma in the basal cisterns. It is not clear whether mechanical vessel compression by macroadenomas causes pituitary apoplexy or whether it results from the sudden expansion of tumor volume induced by pituitary apoplexy. Rosenbaum et al. reported a patient who had pituitary apoplexy 12 hr after angiography (11). They detected focal spasm and occlusion of the internal carotid arteries on follow-up angiography and confirmed the restoration of pulsation after tumor removal. They concluded that the cause of cerebral ischemia was a mechanical obstruction by the tumor. In another report of a case involving cerebral infarction concomitant with pituitary apoplexy, Clark et al. suggested that the nature of the angiographic narrowing was more suggestive of encasement rather than spasm or artheroma (10). On the other hand, other authors have hypothesized that ischemia in the internal carotid artery was the primary event leading to infarction in the pituitary macroadenoma (21, 22).

Although several mechanisms have been suggested, in our case, the causative materials or events leading to chemical meningitis and cerebral infarction are thought to be in the same lineage. There was no definitive evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage on imaging studies or CSF examination. This means that the probable cause was related not to hemorrhage, but to some vasoactive substances from tumor debris or from the pituitary gland. Preoperative vasospasm and ischemia may occur on the very day or even some days after the pituitary apoplexy (9, 14). Surgery, which inevitably destroys the tumor itself, could also precipitate a vascular accident (9, 23). These provide some supporting evidence of a vasospastic material in pituitary adenomas. Despite their rare frequencies, other intracranial neoplasms also can induce vasospasm or ischemia (24). The fact that pituitary adenomas are one of the common disease entities that could coexist with cerebral aneurysm may be a reflection of the intrinsic vasculopathy of pituitary adenomas (25). In a recent report of their histologic and clinical correlations, pituitary apoplexy, hemorrhagic apoplexy, and pure infracted apoplexy exhibited different clinical presentations, courses, and outcomes (26). This also suggests that pituitary apoplexy produces a protean clinical syndrome as a histologic characteristics.

It is likely that, in this sequence, pituitary apoplexy, aseptic chemical meningitis, and cerebral infarction are associated with each other. Pituitary apoplexy occurs as a result of unknown events in preexisting pituitary adenoma; blood or necrotic material induces chemical meningitis, and this could precipitate vasospasm and sometimes overt cerebral infarction. Meningismus after pituitary apoplexy is a sign of meningeal irritation caused by blood or chemical substances from the pituitary adenoma; therefore, early surgical intervention may be suitable, in spite of spinal pleocytosis. This rare case can be a prime example to clarify the chemical characteristics of pituitary apoplexy or pituitary adenoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Hae Sun Lee for her excellent secretarial support for the study.

References

- 1.Onesti ST, Wisniewski T, Post KD. Pituitary hemorrhage into a Rathke's cleft cyst. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:644–646. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199010000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid RL, Quigley ME, Yen SS. Pituitary apoplexy. A review. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:712–719. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060070106028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakai S, Fukushima T, Teramoto A, Sano K. Pituitary apoplexy: its incidence and clinical significance. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:187–193. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.2.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohr G, Hardy J. Hemorrhage, necrosis, and apoplexy in pituitary adenomas. Surg Neurol. 1982;18:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reutens DC, Edis RH. Pituitary apoplexy presenting as aseptic meningitis without visual loss or ophthalmoplegia. Aust N Z J Med. 1990;20:590–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1990.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valente M, Marroni M, Stagni G, Floridi P, Perriello G, Santeusanio F. Acute sterile meningitis as a primary manifestation of pituitary apoplexy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:754–757. doi: 10.1007/BF03347359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouns R, Crols R, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP. Pituitary apoplexy presenting as chemical meningitis. Lancet. 2004;364:502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Jung YS. Pituitary apoplexy presenting as meningitis. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2002;13:94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akutsu H, Noguchi S, Tsunoda T, Sasaki M, Matsumura A. Cerebral infarction following pituitary apoplexy--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004;44:479–483. doi: 10.2176/nmc.44.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JD, Freer CE, Wheatley T. Pituitary apoplexy: an unusual cause of stroke. Clin Radiol. 1987;38:75–77. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbaum TJ, Houser OW, Laws ER. Pituitary apoplexy producing internal carotid artery occlusion. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:599–604. doi: 10.3171/jns.1977.47.4.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lath R, Rajshekhar V. Massive cerebral infarction as a feature of pituitary apoplexy. Neurol India. 2001;49:191–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AK. Pituitary apoplexy in a child presenting with massive subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:94–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pozzati E, Frank G, Nasi MT, Giuliani G. Pituitary apoplexy, bilateral carotid vasospasm, and cerebral infarction in a 15-year-old boy. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:56–59. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semple PL, Webb MK, de Villiers JC, Laws ER., Jr Pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:65–72. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000144840.55247.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubuisson AS, Beckers A, Stevenaert A. Classical pituitary tumour apoplexy: Clinical features, management and outcomes in a series of 24 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2007;109:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebersold MJ, Laws ER, Jr, Scheithauer BW, Randall RV. Pituitary apoplexy treated by transsphenoidal surgery. A clinicopathological and immunocytochemical study. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:315–320. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.3.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishioka H, Ito H, Haraoka J. Cerebral vasospasm following transsphenoidal removal of a pituitary adenoma. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:44–47. doi: 10.1080/02688690020024391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardoso ER, Peterson EW. Pituitary apoplexy and vasospasm. Surg Neurol. 1983;20:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(83)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camp PE, Paxton HD, Buchan GC, Gahbauer H. Vasospasm after trans-sphenoidal hypophysectomy. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:382–386. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee S, Majumder A, Dattamunshi AK, Maji D. Ischaemic stroke leading to left hemiparesis and autohypophysectomy in a case of pituitary macroadenoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;43:801–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovit RL, Fein JM. Pituitary apoplexy: a review and reappraisal. J Neurosurg. 1972;37:280–288. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.37.3.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mawk JR, Ausman JI, Erickson DL, Maxwell RE. Vasospasm following transcranial removal of large pituitary adenomas. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:229–232. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.2.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoki N, Origitano TC, al-Mefty O. Vasospasm after resection of skull base tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;132:53–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01404848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakai S, Fukushima T, Furihata T, Sano K. Association of cerebral aneurysm with pituitary adenoma. Surg Neurol. 1979;12:503–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semple PL, De Villiers JC, Bowen RM, Lopes MB, Laws ER., Jr Pituitary apoplexy: do histological features influence the clinical presentation and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:931–937. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]