Abstract

This study assessed the impact of an 8-week community-based translation of Becoming a Responsible Teen (BART), an HIV intervention that has been shown to be effective in other at-risk adolescent populations. A sample of Haitian adolescents living in the Miami area was randomized to a general health education control group (N = 101) or the BART intervention (N = 145), which is based on the information-motivation-behavior (IMB) model. Improvement in various IMB components (i.e., attitudinal, knowledge, and behavioral skills variables) related to condom use was assessed 1 month after the intervention. Longitudinal structural equation models using a mixture of latent and measured multi-item variables indicated that the intervention significantly and positively impacted all IMB variables tested in the model. These BART intervention-linked changes reflected greater knowledge, greater intentions to use condoms in the future, higher safer sex self-efficacy, an improved attitude about condom use and an enhanced ability to use condoms after the 8-week intervention.

Keywords: adolescence, Haitian, HIV prevention, sexual risk

Despite public health efforts, the highest rates of sexually transmitted diseases are still frequently found among young people in the United States, particularly in minority youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2005). HIV in particular has been an urgent priority in the adolescent population since early in the history of the epidemic when indications emerged that many young adults with AIDS likely had been infected during adolescence. Whereas the latest information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth Risk Behavioral Survey suggested significant reductions in risk behavior for the general adolescent population, a crisis remains for several vulnerable subgroups such as ethnic minorities, youth with psychiatric morbidities including substance disorders, and juvenile offenders (CDC, 2005).

Minority youth are disproportionately represented among adolescents with HIV (CDC, 2005). Inner-city minority youth face a compounded risk due to the higher proportion of HIV in their environments and the high HIV prevalence among ethnic minorities in the United States (Conway et al., 1993). In addition, a larger proportion of minority youth begin engaging in sexual activity earlier than the majority of adolescents, again placing them at heightened risk for contracting the disease. Recent statistics reveal that 32% of African American and 13% of Hispanic males engage in sexual activity before the age of 13, compared to only 7% among Caucasian males (CDC, 2005). This early initiation of sexual activity occurs at a developmental stage when adolescents may not yet have acquired the necessary skills or knowledge to apply safe sex practices (DiClemente, 1991). In fact, one of the most basic neuroanatomic realities is that the human brain does not reach levels of adult complexity, as measured by the Gyrification Index (method for measuring the degree of gyri or convolutions of the brain’s surface, the prevalence of which distinguishes Homo sapiens), until an individual’s early twenties (Andreasen, 2001). Consequently, adolescent HIV prevention interventions must strive to include developmentally appropriate components in addition to, or in place of, frameworks shown to be successful with adult populations (Pedlow & Carey, 2003).

In this study, results are reported from an intervention for adolescents of Haitian descent conducted in Miami-Dade County, which comprises the greater Miami area in Florida. Census data from 2000 indicated a 117% increase in the Floridian Haitian population through the 1990s (Haiti Program at Trinity College, 2003). Immigrants of Haitian descent and their children are one of the largest ethnic groups in the Miami-Dade area of South Florida (Marcelin, McCoy, & DiClemente, 2006). While some Haitians have integrated into the mainstream of American society, most experience economic hardship and other problems related to their lower social status (Marcelin et al., 2006). In Miami’s Metropolitan area, the “Little Haiti” neighborhood contains the major Haitian immigrant population, which has established a specific social, cultural, and linguistic (Creole) presence within Miami Dade County. Yet, multiple structural and psychosocial problems (e.g., inadequate housing, education, and employment; delinquency; and marginalization) exist and may exacerbate HIV transmission and risk behaviors (Malow, Jean-Gilles, Dévieux, Rosenberg, & Russell, 2004).

No HIV prevention intervention has been documented to be effective with Haitian adolescents living in the United States, despite the numeric importance of the Haitian population nationally and in South Florida. Even though the majority is fluently bilingual and considered “acculturated,” U.S. Haitian adolescents may not benefit from interventions originally designed and intended for African American or Anglo populations. Further, there is evidence of persistent gender-related and sexual behavior-related cultural factors that may demand special attention in order to reduce HIV risk behaviors. Our research and that of others have reported on these factors, which are related to power imbalances between sexual partners, taboos on communication about sex between parents and children and between sexual partners, and protraction of the original patriarchal belief system, which often devalues female sexuality and pressures early sexual debut and prowess in males (Magee, Small, Frederic, Joseph, & Kershaw, 2006; Malow, Cassagnol, McMahon, Jennings, & Roatta, 2000; Malow et al., 2004). Early initiation into sex and infrequent condom use has been documented (De Santis & Ugarriza, 1995), although most recently Marcelin et al. (2006) reported that a high percentage of Miami-Dade Haitian-American adolescents affirmed the value of condom use in prevention.

The intervention trial with this special population was approached through a translational design, a process through which an existing intervention found to be effective in one sample is adapted and then evaluated for its effectiveness in a new or different sample (Solomon, Card, & Malow, 2006). Translational research for HIV behavioral prevention has been prioritized by the National Institutes of Health. The evidence-based intervention that we chose for cultural adaptation was Becoming a Responsible Teen (BART). A manual-based adaptation, BART-A, was developed and then an intervention was evaluated in a randomized trial for a target population of Haitian adolescents in Miami.

BART is among the promising HIV prevention interventions for adolescents. Originally developed by St. Lawrence et al. (1995), BART is a cognitive-behavioral intervention based on Fisher and Fisher’s (1992) information-motivation-behavior (IMB) model. The goal of the intervention is to reduce HIV risk by modifying HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behavior. This type of intervention was shown to be highly effective in African American adolescents (St. Lawrence et al. 1995) and demonstrated good outcomes in community-based adolescent samples (St. Lawrence et al., 1995). In particular, previous outcomes have indicated IMB pathways of risk reduction, such as reducing unprotected sex through increased safe sex skills, increasing knowledge about HIV and AIDS, and even delaying the onset of sexual activity (St. Lawrence et al., 1995). The original BART trial reported that outcomes supported Fisher and Fisher’s theory of IMB-guided risk reduction. As reviewed in Fisher, Fisher, and Harman (2003), the IMB model has been found to apply to diverse HIV risk populations, including heterosexual university students, gay men, HIV-infected adolescent males and females, African American adult females, and Indian truck drivers.

IMB theory hypothesizes that HIV-related prevention behaviors, such as condom use, will emerge from the independent constructs of HIV-specific information and motivation as they work through behavioral prevention skills. The latter represents the final pathway to risk reduction behavior outcomes, such as self-reported condom use. However, proxy measures of self-efficacy are typically used as indicators of behavioral skills rather than direct observational assessments, for example, proficiency in correct condom application. As will be noted in the methods section, a condom skills test with a penile model was included in the current study along with condom self-efficacy. In prior work with other populations (e.g., substance abusing juvenile offenders and severely mentally ill adults) it was found that condom self-efficacy (confidence in the ability to use condoms under challenging conditions) was the pivotal and significant predictor of condom use rather than condom use skills per se (Kalichman, Stein, Malow, Averhart, Dévieux & Jennings, 2002). In fact, motivational constructs were key predictors, indicating the importance of motivational-enhancing components or processes in intervention design for these populations. This report focuses on relatively short-term intervention effects particularly related to key constructs in the IMB predictive model.

Methods

Participants

The baseline sample consisted of 246 adolescents of Haitian descent living in the “Little Haiti”/North Miami areas of Miami-Dade County, Florida. Eligible participants were recruited from area schools and Youth Serving Organizations. Inclusion criteria were designed to include males and females between 13 and 18 years of age exhibiting a broad range of risk behaviors. Haitian ethnicity was defined as having one parent or grandparent born in Haiti. The average age was 15.5 years, with 15% in the 7th and 8th grades, 56% in the 9th and 10th grades, and 29% in the 11th and 12th grades. The sample was 70% female. The data reflected the expected acculturation gap between adolescents and their parents; 87% of the adolescents reported that their primary spoken language was English, whereas the primary language spoken at home was Creole/French.

Study Group Assignment

Participants were randomized to the BART adaptation, BART-A (n = 145, 59%), and a Health Promotion Comparison (HPC) condition (n = 101, 41%). A randomized block design was used to control for cross group contamination, and thus minimize possible interaction between the two conditions. Four-week admission blocks were randomly assigned to either BART-A or HPC. Participants admitted during a given time block received the same intervention. Study conditions were time matched, and sessions were divided by gender and conducted in a small group format, with each group composed of 4–8 participants, usually led by male and female co-facilitators. Each intervention was comprised of eight 90-minute sessions, delivered over a period of 8 weeks.

Attrition and Final Study Sample

Assessments conducted 4 weeks after the 8-week intervention sessions were available for 203 of the original 246 participants. The final participant pool had demographic proportions comparable to those at baseline (70% female, mean age = 15.5 years, range = 13–18 years). Group assignment was also highly similar with 57% of the remaining participants in the BART intervention group (N = 116) and 43% (N = 87) in the HPC control group. Attrition analyses were performed using chi-square tests to ensure that those who dropped out were similar to those who continued in the study. In comparisons using continuation (yes/no) as the grouping variable, there were no significant baseline differences for gender, age, prior sexual experience (e.g., vaginal intercourse), performance score on a 9-step condom use demonstration, HIV knowledge, or group membership (experimental vs. control).

Content of BART Adaptation (BART-A) and HPC Conditions

BART is a cognitive behavioral HIV risk reduction intervention specifically designed for use in non-school community settings. The underlying basis for cognitive behavioral approaches comes from social learning theory and the premise that the interactive practice of newly acquired skills plays an important role in the development and maintenance of preventive behavior. The BART specifically provides information to increase factual knowledge about HIV and the consequences of risky sexual behavior, with guidance in developing and practicing refusal skills and other communication skills with potential sexual partners. Role playing of high risk situations is a key medium for developing these skills during group sessions and permits a generative aspect to participation by adolescents as they work through and contribute to the content and scenarios.

The BART adaptation (BART-A) emerged from over a decade of work in Miami in collaboration with its originator (St. Lawrence et al., 1995). Several projects have been undertaken to understand the applicability of BART to different adolescent populations (e.g., Haitians, drug users) and contexts (e.g., more urban, highly fragmented treatment/detention settings). For the Haitian adolescent study, the research team conducted extensive preliminary work over approximately a 1-year period to develop BART-A. Six trial runs were conducted, with successively refined versions of the draft intervention manual. Reactions to each draft protocol were obtained through paper and pencil assessments and focus groups. Refinements were based on this information, feedback from the interventionists, qualitative and quantitative assessments of the adolescent participants, discussions with community leaders and experts in the fields, and new developments in the HIV area. Developing the adaptation involved complex language and cultural translation procedures to engage the youth, parents, and practitioners from the “Little Haiti” Miami community, with particular focus on stigma/acculturation stress.

The adaptation process had the goal of producing change in the same intervention-associated mediating variables (e.g., information, motivation, and behavior) as in the original BART intervention by using similar activities (e.g., role-playing scenarios, instruction, exercises) but with the implementation tailored to cultural values, beliefs and other important characteristics identified in the sample. Therefore, fidelity to the original BART intervention was maintained at the level of the causal “conceptual” model, namely, the theoretical mechanisms of action of the intervention, while adaptation occurs at the level of implementation (Solomon et al., 2006). Also useful was the strategic use of mediating and moderating analyses, recently articulated in the translational research approach of Green and Glasgow (2006).

Attention to moderating variables has typically structured our adaptations, and with BART-A, this resulted in culturally focused strengthening of social competency skills, which were identified as crucial to risk-reduction behavior in the original BART trial, and also to condom use skills. The final iteration, BART-A, included the following components: (a) risk education, (b) group activities to help identify “triggers” of unsafe sex, (c) condom use practice, (d) role-playing of sexual negotiation and refusal, (e) problem-solving approaches to manage risky situations, (f) discussion of risk in intimate relationships, and (g) behavior change maintenance. Skills building in the safer sex role-play scenarios was contextualized to culturally-prescribed gender norms/roles and cultural/spiritual terminology (e.g., linguistically-appropriate and culturally-defined terms for relationships and sexual behaviors). Distinctions between assertive, passive, and aggressive communication styles were drawn out during discussions, with the facilitator modeling the advantages of being assertive, first in nonsexual situations and then in sexual situations. Role plays reinforced these lessons.

The HPC also was manualized and addressed prevention of various diseases and conditions that disproportionately affect minority populations in adulthood by teaching prevention strategies to adolescents. The HPC covered these health-related topics through video presentations and group activities/discussions that were time- and activity-matched to the adapted BART, to control for attention, group interaction, and other non-specific features. To address comparability of HIV information between groups and ethical issues, HIV didactic information was presented in the first session.

Assessment Procedures

Participants were assessed for knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to HIV, alcohol and drug use, and personality variables at baseline and 4 weeks after the end of the 8-week session. Each interview lasted approximately 90 minutes. Participants received $15 gift certificates for their baseline and 4-week follow-up assessments and $5 certificates for each group session they attended.

Measures

The impact of the BART-A intervention on various IMB model constructs was assessed with both multiple-indicator latent variables and single-item sum scores as described below. Because the sample was relatively small, not all variables could be constructed as multiply-indicated latent variables, and some variables did not need to function as latent variables (e.g., a sum score from a test of HIV knowledge). Latent variables are error-free constructs that represent a higher order of abstraction than measured variables (Bentler, 2006). Baseline and 4-week follow-up variables were constructed the same way at both time periods; the baseline variables were hypothesiz ed to predict the same variable assessed 4 weeks post-intervention due to the stability of constructs over time. In addition, membership in the intervention group was hypothesized to impact the variables over and above the expected stable effect of the same variable assessed across time. Gender was initially included as a further covariate but was not significantly associated with any of the variables either pre- or post-intervention. It was dropped in the interest of parsimony and also due to the relatively small sample size.

HIV Knowledge was assessed with 18 true-false items adapted from St. Lawrence et al. (1995). Participants were given a total score based on the number of items they answered correctly.

Condom attitudes about safety

The subscale from the adolescent version of the Condom Attitude Scale (CAS-A) concerned with attitudes and beliefs about the safety of condoms was used at both time periods (St. Lawrence, Reitman, Jefferson, Alleyne, Brasfield, & Shirley, 1994). This subscale had three items scaled from 1 disagree strongly to 4 agree strongly; the mean of the three items was used as a measured variable. A sample item is: Condoms protect against sexually transmitted diseases.

Intentions to use condoms

Behavioral intentions were measured with six items that were combined into three parcels. This scale was derived by simplifying an existing measure (Kalichman, Sikkema, Kelly, & Bulto, 1995). We combined the items to avoid too many indicators of this latent variable especially because the sample was rather small. This is an acceptable method when the coefficient alpha among all of the items is high (in this case, coefficient α. = .75 baseline, .77 at 4-week follow-up) and no clear factor structure can separate the items into meaningful sub-factors (Yuan, Bentler, & Kano, 1997). Items were on a 1–4 scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree; a typical item: I will use a condom the next time I have sex.

Safe sex self-efficacy

Self-efficacy for safe sex was assessed with seven items from the ARMS questionnaire (Gibson, Lovelle-Drache, Young, & Chesney, 1992). These items were combined into three parcels also due to the sample size (coefficient α. = .69 baseline, .75 at 4-week follow-up). Self-efficacy refers to the youth’s belief that he or she could take effective precautionary action. Items were on a 1–4 scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree; typical items included It’s hard to always use condoms. Negatively worded items were reverse-scored as appropriate.

Condom skills test

Condom use skills were assessed by rating the participant’s ability to properly enact the nine steps involved in correctly placing a condom on a penile model (adapted from Sorensen, London, & Morales, 1991). Participants were rated for successful completion of items such as, Opened the condom package without tearing the condom, and Condom rolled to the base of the penile model. Scores reflect the total number of correct steps.

Intervention status

The critical group membership variable in this study was participation in the BART-A condition vs. the HPC condition as described above. BART was coded 1, HPC was coded 0.

Analysis

The analytic method selected for this study was structural equation modeling (SEM) (Bentler, 2006). Sources of measurement error can be partitioned by using latent variables, and simultaneous associations can be controlled effectively by using SEM. The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed with the Satorra-Bentler χ2 (S-B χ2), the Robust Comparative Fit Index (RCFI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (Bentler, 2006). The S-B χ2 was used because the data were multivariately kurtose. The RCFI ranges from 0 to 1 and reflects the improvement in fit of a hypothesized model over a model of complete independence among the measured variables, and also adjusts for sample size. Values at 0.95 or greater are desirable for the RCFI, and a cutoff value less than .06 for the RMSEA is also desirable (Bentler, 2006).

The model tested predictive stability paths from similar constructs across the 12-week period (e.g., HIV Knowledge at baseline predicted HIV Knowledge at the 4-week follow-up after the 8-week session) and the additional predictive path of intervention group membership (e.g., Aiken, Stein, & Bentler, 1994) for the entire sample. Including baseline scores helped ensure that pre-existing differences did not account for a positive influence of the intervention on the various IMB model components. In addition, although the sample was randomized into the two groups, intervention status was initially correlated with all baseline variables to control for any inadvertent pre-existing positive or negative associations between intervention status and prior behaviors. Non-significant correlations were dropped from the analysis to keep the model as parsimonious as possible due to the small sample size. Baseline variables were allowed to correlate among themselves. Cross-construct paths from the pre-test to the post-test were not originally hypothesized to be part of the model but a few were added based on suggestions from the LaGrange Multiplier (LM) test (Bentler, 2006). The LM test suggests additional relationships to add to models for fit improvement. It was reasonable to allow for the addition of cross-construct influences in this model that was assessing knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to condom use as they are hypothesized to relate highly.

Results

Table 1 presents the factor loadings of the measured variables on their hypothesized latent variables and the means and standard deviations of the measured variables in a preliminary confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model. All items constructed for the latent variables loaded significantly (p < .001) on their hypothesized factors. Although the 2 groups were not assessed separately, means and standard deviations are also presented for the separate groups for completeness and for reader interest. Table 2 presents the bivariate correlations among all of the variables included in the CFA model before the across-time analysis was performed. Of note, intervention group membership was not significantly related to any baseline measures except for a small pre-existing advantage for those in the intervention group in their condom skills.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Combined Group (N = 203), Intervention Group (N = 116), and Control Group (N = 87); Factor Loadings of the Latent Variables

| Total sample | Intervention | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Factor loading | |

| Pre- Test | ||||

| 1. HIV knowledge | 13.35 (2.57) | 13.34 (2.65) | 13.36 (2.47) | ----- |

| 2. Condom Attitude re: Safety | 3.15 (0.65) | 3.17 (0.67) | 3.13 (0.63) | ----- |

| 3. Intentions to Use Condoms | ||||

| Intent 1-pretest | 3.72 (0.64) | 3.69 (0.68) | 3.75 (0.59) | .47 |

| Intent 2-pretest | 3.55 (0.70) | 3.53 (0.73) | 3.58 (0.65) | .68 |

| Intent 3-pretest | 3.59 (0.72) | 3.56 (0.79) | 3.63 (0.62) | .83 |

| 4. Safe Sex Self-Efficacy | ||||

| Self-Efficacy 1-pretest | 3.02 (0.69) | 2.96 (0.63) | 3.11 (0.76) | .81 |

| Self-Efficacy 2-pretest | 3.23 (0.76) | 3.20 (0.76) | 3.28 (0.76) | .70 |

| Self-Efficacy 3-pretest | 3.24 (0.69) | 3.20 (0.70) | 3.28 (0.76) | .48 |

| 5. Condom Skills Test | 0.47 (0.25) | 0.50 (0.25) | 0.43 (0.25) | ------ |

| Post Test | ||||

| 6. HIV knowledge | 14.22 (2.55) | 14.45 (2.29) | 13.90 (2.86) | ------ |

| 7. Condom Attitude re: Safety | 3.43 (0.55) | 3.58 (0.48) | 3.22 (0.56) | ------ |

| 8. Intentions to Use Condoms | ||||

| Intent 1-post-test | 3.82 (0.51) | 3.87 (0.41) | 3.76 (0.62) | .44 |

| Intent 2-post-test | 3.66 (0.60) | 3.73 (0.55) | 3.56 (0.65) | .86 |

| Intent 3-post-test | 3.73 (0.63) | 3.82 (0.51) | 3.61 (0.74) | .72 |

| 9. Safe Sex Self-Efficacy | ||||

| Self-Efficacy 1-post-test | 3.31 (0.66) | 3.40 (0.63) | 3.18 (0.68) | .76 |

| Self-Efficacy 2-post-test | 3.55 (0.62) | 3.61 (0.59) | 3.46 (0.65) | .64 |

| Self-Efficacy 3-post-test | 3.44 (0.67) | 3.54 (0.64) | 3.30 (0.70) | .72 |

| 10. Condom Skills Test | 0.71 (0.24) | 0.80 (0.18) | 0.59 (0.27) | ----- |

| 11. Intervention group member | 0.58 (0.50) | ------ | ------ | ----- |

Note. All factor loadings are significant (p < .001). N.A. = not applicable. Intent 1–3 and Self-Efficacy 1–3 refer to the 3 factor loadings at pre-test and post-test.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Latent and Measured Variables

| Pre-test | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HIV knowledge | --- | |||||||||

| 2. Condom Attitude re: Safety | −.06 | --- | ||||||||

| 3. Intentions to Use Condoms | .21** | .12 | --- | |||||||

| 4. Safe Sex Self- Efficacy | .32*** | .14 | .29** | --- | ||||||

| 5. Condom Skills Test | .23*** | −.06 | .11 | .24** | --- | |||||

| Post-Test | ||||||||||

| 6. HIV knowledge | .64*** | .14* | .28*** | .32*** | .19** | --- | ||||

| 7. Condom Attitude re: Safety | .07 | .33*** | .04 | .17* | .11 | .24*** | --- | |||

| 8. Intentions to Use Condoms | .33*** | .13 | .37** | .13 | .05 | .50*** | .31*** | --- | ||

| 9. Safe Sex Self- Efficacy | .36*** | .24** | .17* | .67*** | .11 | .41*** | .40*** | .43*** | --- | |

| 10. Condom Skills Test Score | .09 | −.11 | -.03 | .03 | .28*** | .10 | .20** | .03 | .13 | --- |

| 11. Intervention group member | −.01 | .03 | −.06 | −.11 | .15* | .11 | .33*** | .18* | .22** | .42*** |

Note. p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

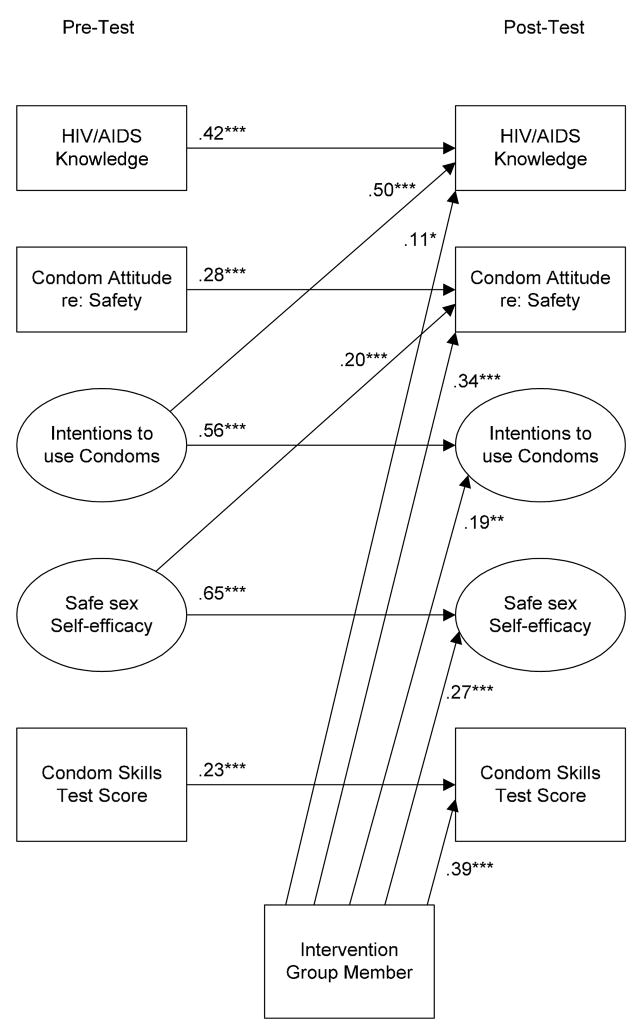

Figure 1 presents the results of the analysis of the hypothesized path model. Fit indexes for the path model are quite good: S-B χ2 (127, N = 203) = 165.48, RCFI = .95, RMSEA = 0.039. Fit was improved by the addition of two non-hypothesized predictive pathways: one is from higher Intentions to use Condoms at baseline to greater HIV Knowledge at follow-up; the other is from Safe Sex Self-Efficacy at baseline to greater Condom Attitudes about Safety of Condoms. All across-time paths are standardized partial regression coefficients. Covariances (correlations) among the predictors are not depicted in the figure for readability. However, the correlations among the predictors are similar to those reported in Table 2. Non-significant correlations among the predictor variables were dropped gradually from the final model.

Figure 1.

Final structural path model depicting stability across time and impact of the intervention. All estimated parameters are standardized. The large circles designate latent variables; the rectangles represent measured variables. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression paths. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Stability paths were generally substantial as expected after the relatively short time lag of 12 weeks after baseline (all p < .001). It is of greater note that the intervention group members scored significantly higher on every component of the model: greater knowledge (p < .05), greater intentions to use condoms in the future (p < .01), higher safe sex self-efficacy (p < .001), an improved attitude about condom use as a safety measure (p < .001), and higher scores and significant improvement in the ability to use a condom at 4-week post intervention (p < .001). In two instances, the predictive path from intervention group membership was larger than that of the stability path indicating substantial changes in attitudes or behaviors. In the case of the Condom Skills Test Score, the predictive path from group membership to the outcome score was higher than the stability path (.39 vs. .23). In the case of Condom Attitudes about Safety, the stability path was .28 and the path from group membership was .34.

Discussion

There was a substantial positive influence on important IMB constructs by the specialized BART-A program tailored for Haitian adolescents. At the 4-week post-intervention point, membership in the intervention group positively and significantly affected all variables tested in the model. These variables included key IMB components of greater knowledge, greater intentions to use condoms in the future, higher safe sex self-efficacy, and an improved attitude about condom use as a safety measure. Also, in terms of behavioral skills, the intervention group showed much higher scores and significant improvement in the ability to use a condom, a key aspect of HIV-risk reduction.

Participants in our study demonstrated somewhat lower pre-intervention levels of knowledge relevant to HIV infection risk and related risky behaviors than had been found in other groups of minority adolescents (St. Lawrence, Crosby, Brasfield & O’Bannon, 2002). Furthermore, the BART-A group demonstrated modest gains in knowledge comparable to those found in previous BART intervention studies (St. Lawrence et al., 2002). The relatively limited pre-intervention knowledge level in this group and modest intervention-linked gains suggest the need to place more emphasis on transmitting knowledge among vulnerable and underserved populations, including minority adolescents, about HIV infection risk and risk reduction strategies. This result was a reminder that HIV-related information, including susceptibility to infection, continues to be an important component for interventionists to attend to and investigate, particularly among newly-arrived or understudied populations. We should not assume that adolescents know about HIV transmission pathways even though this information seems to have been widely disseminated during the past several years.

Condom-use skills remain a key indicator of risk reduction, and skill mastery in using both male and female condoms was emphasized in the BART-A. Intervention participants demonstrated substantial gains in positive attitudes regarding condom use as a safety measure. Similarly beneficial changes have been reported in studies of BART effects among substance dependent adolescents (St. Lawrence et al., 2002). Improvements in condom attitudes have been linked with reductions in risk behavior in a number of studies (Albarracín et al. 2005).

In contrast to results of a study of Haitian women from South Florida with moderately unfavorable personal and partner attitudes regarding condom use (Malow et al., 2000), he group of adolescents in this study, although from the same community as the women, revealed moderately favorable pre-intervention attitudes regarding condom use as a safety measure and impressive intervention-linked improvement. Perhaps these more favorable attitudes regarding condom use and contraception among this group of adolescents are related to age differences and variations in the degree of acculturation. In subsequent studies it will be important to evaluate possible acculturative mechanisms associated with development of favorable condom attitudes and intervention linked attitude and behavioral change.

Behavioral intentions to use condoms have been associated with adoption of protective behavior in a number of studies (i.e., Albarracín et al. 2005). In this investigation, pre-intervention condom use intentions were generally favorable. Modest improvements were observed at follow-up among BART-A members. This finding is consistent with that of St. Lawrence et al. (2002) in which improvements in attitudes toward prevention, including behavioral intentions, were linked with BART interventions involving both information and behavioral skills training components. It is also noteworthy that intentions to use condoms at pre-intervention predicted HIV knowledge at follow-up. Interestingly, pre-intervention intentions were more strongly predictive of follow-up knowledge than was pre-intervention knowledge. Positive initial condom use intentions are apparently linked with a readiness to acquire more HIV knowledge over the course of intervention.

Self-efficacy is a fundamental element in social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994) and an important feature of the behavioral skills component in the IMB model (Fisher et al. 2003). Generally, at pre-intervention, Haitian adolescent participants reported only moderate confidence in their ability to enact safer sexual practices. They seemed to realistically appraise challenges associated with consistent condom use, especially “when really turned on” or with “someone you really know.” St. Lawrence et al. (2002) found improvements on a measure of safer sex self-efficacy among adolescent substance abuse participants in a BART component analysis involving comparison of an information only condition, an information plus behavioral skills condition, and a third that added motivational enhancement to information and skills training. However, improvement in self-efficacy was not linked to the enhanced conditions, which represented essential behavioral and motivational components of the IMB-linked BART model. In contrast, in the current investigation, BART-A did produce meaningful improvements in participant’s beliefs in personal effectiveness in taking precautionary action. Further, initially higher levels of safer sex self-efficacy contributed to greater post-intervention improvements in condom attitudes. Previously, self-efficacy has been found to be predictive of levels of risk behavior in a cross-sectional study of BART-relevant mediator variables and sex risk behavior in a sample of adolescents from the Northern District of Haiti (Holschneider & Alexander, 2003).

The IMB model indicates that behavioral skills must be developed prior to effectively engaging in related health protective behaviors. Such skills include verbal and non-verbal abilities and other behavioral competencies that are hypothesized to be directly linked to self-efficacy (Fisher et al., 2003). One essential skill component emphasized in the BART intervention involves safe and effective use of condoms. Substantial intervention-linked improvements in condom use skills were observed at follow-up. Our findings are consistent with those of Fisher, Fisher, Bryan, and Misovich (2002) who also demonstrated improvements in condom-use skill acquisition and reductions in HIV risk behaviors in an IMB-focused, school-based intervention with minority inner-city adolescents.

Conclusion

Results from this study support previous investigations that demonstrated the feasibility of conducting group-based community HIV risk reduction interventions for at-risk ethnic-minority youth (St. Lawrence et al., 2002). Current findings also contribute to a growing literature suggesting the value of translational research: adapting an evidence-based intervention, which has been effective in diverse U.S. populations, to fit the needs of an understudied and underserved group. To our knowledge, BART-A is the first HIV prevention trial to address the specific needs of Haitian adolescents living in the United States. During sessions, Haitian youth were helped in developing a specific personal risk-reduction plan that might be both relevant and realistically accomplished with a sense of mastery and success. Results also indicate modification of several theoretically-anchored antecedents of risk behavior in an IMB-guided intervention adapted specifically for our sample. Although the limited length of follow-up in the current investigation did not allow analysis of intervention effects on risk behavior, it did demonstrate meaningful improvements in attitudes and skills that have been linked to behavioral risk reduction in other studies, including the Holschneider and Alexander (2003) cross-sectional study involving adolescents living in Haiti. Changes in condom attitudes, enhanced self-efficacy in adopting safer practices, and improvements in condom use skills demonstrated in this study suggested that BART may be a useful initial tool in encouraging adoption of safer practices. Current findings also indicated the importance of emphasizing HIV-related knowledge, including that related to biological susceptibility to infection, among newly-arrived or understudied populations.

Fisher, Nadler, et al. (in press) have recently examined the applicability of the IMB model for populations with multiple needs and barriers, including resource-poor populations both here and in other countries. As they explain, the model has increasingly been applied to HIV-risk populations facing adherence issues, and consequently problems of compliance in following preventive or therapeutic regimens requiring access to and utilization of health care and other resources. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment is a notable example. Fisher, Nadler et al., (in press) organized the HIV prevention field’s focus on “long-term autonomous behavior change” and a target of combining access to and utilization of objective resources with components that will address critical information, motivation, and behavioral skills. The call for more structural HIV interventions has needed a certain structure in order to proceed. Just as condom use requires autonomous agency, so does the use of available and planned structures. Future research with populations at risk for HIV will need to move to this integrative horizon in translational research, adding components to evidence-based interventions that improve access, help-seeking skills, and utilization of specific resources to reinforce positive behavioral gains.

Clinical Considerations

Haitian adolescents may be at particular risk for HIV/STIs due to cultural factors that affect their sexual risk behaviors. Haitian adolescents, particularly girls, may not be comfortable discussing sexual issues.

HIV prevention interventions are most effective when they are gender-specific and culturally-tailored to a particular population.

Adapting an evidence-based intervention, which has been effective in diverse U.S. populations, can provide the base of a useful intervention in an untested group.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by R01 HD38458 from NICHD and P01-DA01070-35 from NIDA. We acknowledge the extensive assistance of Laurinus Pierre, MD, MPH of the Center for Haitian Studies in helping with the logistics of conducting the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiken LS, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Structural equation analyses of clinical sub-population differences and comparative treatment outcomes: Characterizing the daily lives of drug addicts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:488–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho MH. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: A comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;31:856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Brave new brain: Conquering mental illness in the era of the genome. London: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, editor. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2004. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Retrieved November, 1, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/youth.htm#9. [Google Scholar]

- Conway GA, Epstein MR, Hayman CR, Miller CA, Wendell DA, Gwinn M, et al. Trends in HIV prevalence among disadvantaged youth. Survey results from a national job training program, 1988 through 1992. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:2887–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santis L, Ugarriza DN. Potential for intergenerational conflict in Cuban and Haitian immigrant families. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1995;9:354–364. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(95)80059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ. Predictors of HIV-preventive sexual behavior in a high-risk adolescent population: The influence of perceived peer norms and sexual communication on incarcerated adolescents’ consistent use of condoms. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:385–390. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90052-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model as a general model of health behavior change: Theoretical approaches to individual-level change. In: Suls J, Wallston K, editors. Social psychological foundations of health. London: Blackwell Publishers; 2003. pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychology. 2002;21:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Nadler A, Little JS, Saguy T. Help as a vehicle to reconciliation, with particular reference to help for extreme health needs. In: Nadler A, Malloy TE, Fisher JD, editors. Social Psychology of Inter-Group Reconciliation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; In Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DR, Lovelle-Drache J, Young MT, Chesney M. HIV risk linked to psychopathology in IV drug users. International Conference on AIDS; 1992. Abstract POC 4691. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation & Health Professions. 2006;29:126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiti Program at Trinity College. Haitians in America. 2003 Retrieved September 26, 2008, from http://www.haiti-usa.org/modern/index.php.

- Holschneider SO, Alexander CS. Social and psychological influences on HIV preventive behaviors of youth in Haiti. Journal of Adolescence Health. 2003;33:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Stein J, Malow RM, Averhart C, Dévieux J, Jennings T. Predicting protected sexual behavior using the Information-Motivation-Behavior Skills (IMB) model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychology Health and Medicine. 2002;7:327–338. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Bulto M. Use of a brief behavioral skills intervention to prevent HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:275–280. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee EM, Small M, Frederic R, Joseph G, Kershaw T. Determinants of HIV/AIDS risk behaviors in expectant fathers in Haiti. Journal of Urban Health -Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83:625–636. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9063-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, Cassagnol T, McMahon R, Jennings TE, Roatta VG. Relationship of psychosocial factors to HIV risk among Haitian women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:79–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, Jean-Gilles MM, Dévieux JG, Rosenberg R, Russell A. Increasing access to preventive health care through cultural adaptation of effective HIV prevention interventions: A brief report from the HIV prevention in Haitian Youths Study. The ABNF Journal. 2004;15:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelin LH, McCoy HV, DiClemente RJ. HIV/AIDS knowledge and beliefs among Haitian adolescents in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children and Youth. 2006;7:121–138. doi: 10.1300/J499v07n01_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow CT, Carey MP. HIV sexual risk-reduction interventions for youth: A review and methodological critique of randomized controlled trials. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:135–190. doi: 10.1177/0145445503251562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions: Advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29:162–194. doi: 10.1177/0163278706287344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, London J, Morales E. Group counseling to prevent AIDS. In: Sorensen J, Wermuth JL, Gibson DR, Choi KH, Guydish J, Batki S, editors. Preventing AIDS in drug users and their sexual partners. New York: Guilford; 1991. pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Brasfield TL, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, O’Bannon RE, Shirley A. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce African-American adolescents’ risk for HIV infection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:221–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Crosby RA, Brasfield TL, O’Bannon RE., III Reducing STD and HIV risk behavior of substance-dependent adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1010–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Reitman D, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL, Shirley A. Factor structure and validation of an adolescent version of the Condom Attitude Scale: An instrument for measuring adolescents’ attitudes towards condoms. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:352–359. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, Bentler PM, Kano Y. On averaging variables in a confirmatory factor analysis model. Behaviormetrika. 1997;24:71–83. [Google Scholar]