Abstract

Many potential uses of direct gene transfer into neurons require restricting expression to one of the two major types of forebrain neurons, glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons. Thus, it is desirable to develop virus vectors that contain either a glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific promoter. The brain/kidney phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG), the product of the GLS1 gene, produces the majority of the glutamate for release as neurotransmitter, and is a marker for glutamatergic neurons. A PAG promoter was partially characterized using a cultured kidney cell line. The three vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs) are expressed in distinct populations of neurons, and VGLUT1 is the predominant VGLUT in the neocortex, hippocampus, and cerebellar cortex. Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) produces GABA; the two molecular forms of the enzyme, GAD65 and GAD67, are expressed in distinct, but largely overlapping, groups of neurons, and GAD67 is the predominant form in the neocortex. In transgenic mice, an ∼9 kb fragment of the GAD67 promoter supports expression in most classes of GABAergic neurons. Here, we constructed plasmid (amplicon) Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) vectors that placed the Lac Z gene under the regulation of putative PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters. Helper virus-free vector stocks were delivered into postrhinal cortex, and the rats were sacrificed 4 days or 2 months later. The PAG or VGLUT1 promoters supported ∼90 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression. The GAD67 promoter supported ∼90 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression. Long-term expression was observed using each promoter. Principles for obtaining long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors, based on these and other results, are discussed. Long-term glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression may benefit specific experiments on learning or specific gene therapy approaches. Of note, promoter analyses might identify regulatory elements that determine a glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron.

Keywords: herpes simplex virus vector, glutamatergic neuron-specific expression, GABAergic neuron-specific expression long-term expression, cortical neuron

1. Introduction

Due to the heterogeneous cellular composition of specific brain areas, neuronal subtype-specific expression is required for many potential uses of direct neural gene transfer. The two predominant types of forebrain neurons are glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, although the classification of classes of neurons within each type remains controversial [28,29,41]. Thus, it is desirable to develop vectors that support either glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression. One approach is to exploit promoters that are specific for either glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons. Vectors containing such promoters could restrict recombinant expression to either type of neuron, and, conversely, analyses of these promoters might identify the critical regulatory elements that determine a glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron.

Glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific promoters might be obtained from specific genes for neurotransmitter biosynthetic enzymes or vesicular transporters. The brain/kidney phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG [2]), the product of the GLS1 gene, produces the majority of the glutamate for release as neurotransmitter [16], and PAG knockout mice show a reduction in depolarization-evoked glutamate release [27]. PAG has been used as an immunohistochemical marker for glutamatergic neurons [20,21,35,50]. The rat PAG promoter was cloned and partially characterized by DNA transfection studies in a cultured kidney cell line [49], but no analyses in neuronal cells have been reported to date. The three vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUT1, VGLUT2, VGLUT3) are expressed in distinct populations of neurons (review [13]). VGLUT1 is the predominant VGLUT in the neocortex, hippocampus, cerebellar cortex, and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala; VGLUT2 is found in the thalamus, deep cerebellar nuclei, hypothalamus, brainstem, and in some neurons in layer 4 of neocortex; and VGLUT3 is found in neurons traditionally viewed as non-glutamatergic [3,12,13,17,46,47,51]. VGLUT1 knockout mice show large reductions in glutamatergic neurotransmission and quantal size [56]. There are no published studies on the VGLUT1 promoter. Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) produces GABA, and the two GAD isoforms are encoded by two genes, GAD65 and GAD67 [8]. GAD65 and GAD67 are expressed in distinct, but largely overlapping, types of neurons, and GAD67 is the predominant form in the neocortex [8-10]. Both the GAD65 [1,24,26] and GAD67 [5,7,15,23,25,30,31,48] promoters have been analyzed in transgenic mice, and an ∼9 kb fragment of the GAD67 promoter is sufficient to support expression in most types of GABAergic neurons.

Helper virus-free Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) plasmid vectors [11] (amplicons) are attractive for gene transfer into neurons because they efficiently transduce neurons, have a large capacity (51 kb or 149 kb HSV-1 vectors have been reported [52,54]), and can support long-term neuronal-specific, or neuronal subtype-specific, expression from specific cellular promoters. Specifically, the preproenkephalin (preproENK) promoter supported long-term (2 months) expression in specific brain areas containing enkephalinergic neurons (ventromedial hypothalamus or amygdala, helper virus system [22]). Large fragments of the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; 6.8 kb or 9 kb) promoter supported long-term (2 months) expression in midbrain dopaminergic neurons (helper virus system [18,38]; helper virus-free system [55]). Of note, vectors containing the TH promoter supported 40 to 60 % nigrostriatal neuron-specific expression [38,55], compared to only 5 % using an vector containing the HSV-1 immediate early 4/5 promoter [38]. A vector containing a neurofilament heavy gene (NF-H) promoter supported neuronal-specific expression, but expression was only short-term [55]. To obtain long-term, neuronal-specific expression, we previously constructed chimeric promoters that fused an upstream enhancer from the TH promoter to the NF-H promoter (TH-NFH promoter) or placed a β-globin insulator (INS) upstream of the TH-NFH promoter (INS-TH-NFH promoter) [59]. The TH-NFH promoter supported long-term expression in two different neocortical areas (1 month), hippocampus (2 months), or striatum (6 months; helper virus-free system) [59]. At 6 months after gene transfer, vectors containing the INS-TH-NFH promoter supported expression in ∼11,400 striatal neurons (using 3 sites for gene transfer), and expression was maintained for 14 months [42]. The TH-NFH or INS-TH-NFH promoters supported ∼90 % neuronal-specific expression in the striatum, hippocampus, or neocortex [42,58,59]. However, glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression has not been reported using a virus vector system.

In this study, we inserted the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters into HSV-1 vectors, and delivered these vectors into rat postrhinal (POR) cortex. The PAG or VGLUT1 promoters supported ∼90 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression, and the GAD67 promoter supported ∼90 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression. These promoters supported expression for 2 months after gene transfer.

2. Results

2.1. HSV-1 vectors containing the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters are efficiently packaged into HSV-1 particles

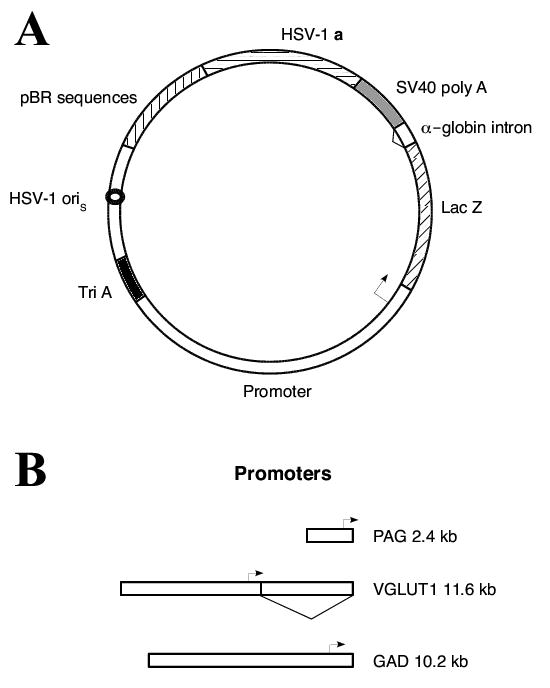

Putative promoter sequences from the rat PAG, mouse VGLUT1, or mouse GAD67 genes were substituted for the TH-NFH promoter in the vector pTH-NFHlac [59], to yield pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac (Fig. 1). These vectors (Fig. 1A) placed the Lac Z gene under the control of each of these promoters (Fig. 1B). The first intron from the VGLUT1 gene was included in pVGLUT1lac because this intron may have a role in regulating expression (Dr. Herzog, personal communication).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams of (A) the vector backbone common to all constructs, and (B) the rat PAG, mouse VGLUT1, and mouse GAD67 promoters. (A) The transcription unit contains the promoter region (clear segment), followed by the Lac Z gene (diagonal line segment), the second intron from the mouse α-globin gene (triangle), and the SV40 early region polyadenylation signal (SV40 poly A, gray). Three polyadenylation sites (Tri A, black) were placed 5′ to the promoter segment, to minimize effects on each promoter from the upstream HSV IE 4/5 promoter. Two sequences from HSV-1 were included to support DNA replication (HSV-1 oriS, small circle) and packaging into HSV-1 particles (HSV-1 a, horizontal line segment). To allow propagation in E. coli, sequences from pBR322 (vertical lines) were included. (B) The three promoters are drawn to scale relative to each other; the sizes and transcription start sites are indicated. The triangle denotes the first intron in the VGLUT1 gene.

Using a helper-virus free packaging system [11,45], each of these vectors was packaged into HSV-1 particles. To quantify the numbers of infectious virus particles (IVP/ml), the purified vector stocks were titered on Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK) cells; at 1 day after transduction, positive cells were visualized using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal) staining (Table 1). The titers ranged from 6.5 to 8.6 × 106 IVP/ml. This titering was performed on BHK fibroblast cells as the best available assay; these fibroblast cells form a monolayer. In contrast, PC12 cells, and most neuronal cell lines, do not form a monolayer. The titers obtained on BHK cells are higher than the titers obtained on PC12 cells [57,59]. Expression from these neuronal subtype-specific promoters in fibroblast cells represents ectopic expression that declined rapidly at longer times after gene transfer (not shown). Next, the titers of vector genomes (VG/ml) were determined by performing a PCR assay on DNA isolated from these vector stocks (Table 1). The packaging efficiency was quantified by evaluating the ratio of VG:IVP (Table 1), and the ratios ranged from 12 to 19 for these vector stocks. The IVP/ml, VG/ml, and ratios of VG:IVP observed for these vector stocks are similar to the titers and ratios obtained using vectors that contain the TH-NFH promoter [57,59].

TABLE 1.

Titers of the purified vector stocks

| Vector | VG/mla | IVP/mlb | VG/IVP |

|---|---|---|---|

| pPAGlac | 1.6×108 | 8.6×106 | 19 |

| pVGLUT1lac | 9.6×107 | 6.5×106 | 15 |

| pGADlac | 8.9×107 | 7.5×106 | 12 |

VG/ml is vector genomes/ml.

IVP/ml is infectious virus particles/ml.

We did not perform experiments in cultured cells to examine glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression, because a suitable cell culture system is not available. Neuronal cell lines differ in important properties from neurons in the brain; thus, results on a specific promoter obtained in a cell line do not always apply to neurons in the brain. Another alternative is cultured neurons, but cultured neurons are usually prepared from late gestation embryos or newborn rodents; and because the promoters studied here are developmentally regulated, results obtained in cultured neurons may not reflect the properties of the promoters in mature neurons in adult rats. Additionally, the GAD67 promoter has already been established in transgenic mice [5,7,15,23,25,30,31,48], with qualitatively similar results in transfected brain slices [19], rendering additional cell culture studies redundant. Thus, as detailed next, we quantified glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression in mature neocortical neurons in the young adult rat brain. Although we did not measure levels of expression per cell, expression levels were sufficient to support both X-gal and immunofluoresence assays.

2.2. Vectors containing the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters support glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression in rat POR cortex

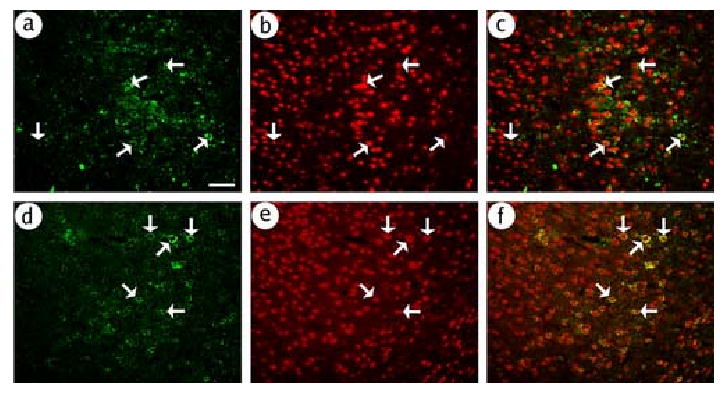

First, we established immunofluoresence assays to detect either glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons. We chose an anti-PAG antibody to identify glutamatergic neurons, and an anti-GAD antibody to identify GABAergic neurons. Sections from rat POR cortex were costained for either PAG-immunoreactivity (IR) or GAD-IR and a marker for neurons, NeuN-IR. PAG-IR (Fig. 2A-C) or GAD-IR (Fig. 2D-F) each stained a subset of neurons.

Fig. 2.

The PAG-IR and GAD-IR assays recognize specific subpopulations of cortical neurons. Sections that contained POR cortex were obtained from a rat that did not receive gene transfer. PAG-IR or GAD-IR was visualized using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody, and NeuN-IR was visualized in the same sections using a rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody. (A-C) PAG-IR stains a subset of neurons; (A) PAG-IR, (B) NeuN-IR, or (C) merged. Numerous neurons were detected, many of which contained PAG-IR (arrows). (D-F) GAD-IR stains a subset of neurons; (D) GAD-IR, (E) NeuN-IR, or (F) merged. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Stocks of each of the vectors (pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac) were microinjected into rat POR cortex, and the rats were sacrificed at 4 days after gene transfer. The histological analysis focused on the transduced cells in POR cortex, because we previously showed that delivery of a vector containing a neuronal-specific promoter (INS-TH-NFH promoter) into POR cortex resulted in expression predominantly in POR cortex cells, with minimal expression in specific cortical areas with large projections to POR cortex, and no detectable expression in a large number of specific subcortical areas [58]. We used the immunofluoresence assays just described to evaluate the cell type specificity of expression; β-galactosidase (β-gal)-IR was localized to glutamatergic neurons by costaining for PAG-IR, or to GABAergic neurons by costaining for GAD-IR, or to all neurons by costaining for NeuN-IR. The injection site coordinates specify a site deep in POR cortex, and most of the transduced cells were located deep in POR cortex; however, we did not determine the distribution of the different types of transduced cells among the different cortical layers.

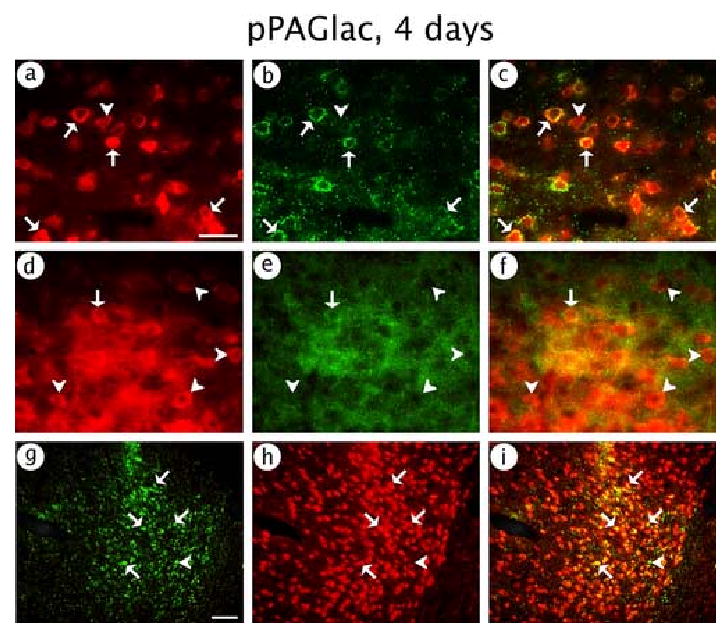

pPAGlac supported expression in glutamatergic neurons, as shown by a high level of costaining for β-gal-IR and PAG-IR (Fig. 3A-C); however, some β-gal-IR cells lacked PAG-IR. In contrast, we observed only low levels of expression in GABAergic neurons, as shown by limited costaining for β-gal-IR and GAD-IR (Fig. 3D-F). Consistent with glutamatergic neuron-specific expression, the vast majority of the expression was in neurons, as shown by a high level of costaining for β-gal-IR and NeuN-IR (Fig. 3G-I). Cell counts (Table 2) showed that 87 % of the expression was in glutamatergic neurons, and only 11 % of the expression was in GABAergic neurons. The sum of the counts of expression in glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons (87 % + 11 % = 98 %) showed that almost all of the expression was in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, consistent with 97 % neuronal-specific expression from counts of the NeuN-IR costaining (Table 2). As virtually all the expression was in neurons, we did not perform costaining for β-gal-IR and markers for specific types of glia.

Fig. 3.

pPAGlac supported expression of β-gal predominantly in glutamatergic neurons. The rat was sacrificed at 4 days after gene transfer. β-gal-IR was detected using an anti-β-gal antibody, and glutamatergic neurons, or GABAergic neurons, or all neurons, were identified using anti-PAG, or anti-GAD, or anti-NeuN antibodies, respectively. (A-C) Glutamatergic neuron-specific expression; (A) β-gal-IR, (B) PAG-IR, or (C) merged. (D-F) GABAergic neuron-specific expression; (D) β-gal-IR, (E) GAD-IR, or (F) merged. (G-I) Neuronal-specific expression; (G) β-gal-IR, (H) NeuN-IR, or (I) merged. Arrows indicate costained cells, and arrowheads show cells that contained only β-gal-IR. Scale bars: (A-F) 50 μm; (G-I) 100 μm.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of cells that contained β-gal-IR, and the types of transduced cells, in rats sacrificed at 4 days after injection of pPAGlac into POR cortex

| Cell marker | β-gal-IR cells | Costained cellsa | % costained |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAG | 538 | 470 | 87 |

| GAD | 269 | 29 | 11 |

| NeuN | 253 | 245 | 97 |

The titers of pPAGlac are in Table 1. Gene transfer used 1 injection site/hemisphere (see methods for stereotactic coordinates), and 3 μl of vector stock was injected. Three hemispheres were analyzed, and 3-6 sections were analyzed in each hemisphere. All the β-gal-IR cells in each section that was examined were scored for costaining with the appropriate cell marker.

Costained cells are positive for both β-gal-IR and cell marker-IR.

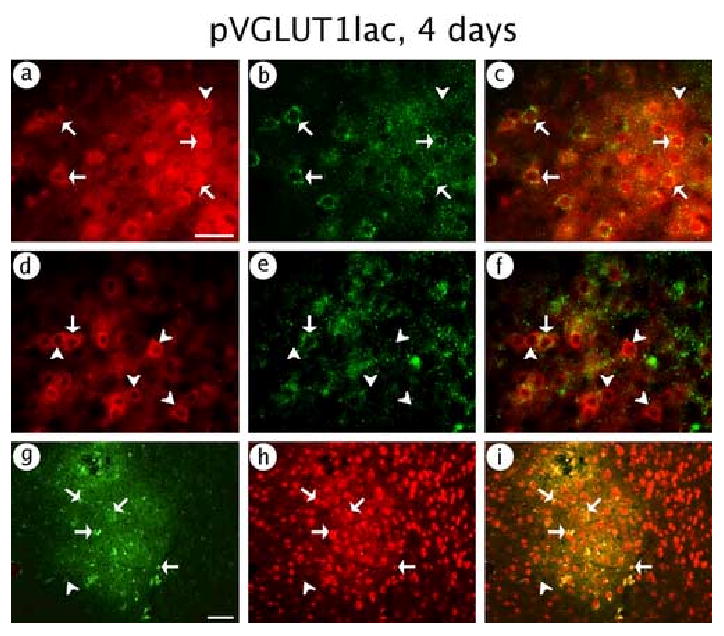

pVGLUT1lac also supported expression in glutamatergic neurons. Of note, we observed a high level of costaining for β-gal-IR and PAG-IR (Fig. 4A-C), although a few β-gal-IR cells lacked PAG-IR. Conversely, pVGLUT1lac supported only limited expression in GABAergic neurons, as shown by low levels costaining for β-gal-IR and GAD-IR (Fig. 4D-F). Also, almost all of the expression was in neurons, as shown by a high level of costaining for β-gal-IR and NeuN-IR (Fig. 4G-I). Cell counts (Table 3) showed that 92 % of the expression was in glutamatergic neurons, but only 11 % of the expression was in GABAergic neurons. The sum of the counts of expression in glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons (92 % + 11 % = 103 %) showed that the vast majority of the expression was in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, and counts of the NeuN-IR costaining showed 97 % neuronal-specific expression (Table 3). Because the assays for glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons use different antibodies with different sensitivities, the sum of the counts of these two types of neurons (103 %) was slightly over 100 %.

Fig. 4.

pVGLUT1lac supported expression of β-gal predominantly in glutamatergic neurons. The rat was sacrificed at 4 days after gene transfer. (A-C) Glutamatergic neuron-specific expression; (A) β-gal-IR, (B) PAG-IR, or (C) merged. (D-F) GABAergic neuron-specific expression; (D) β-gal-IR, (E) GAD-IR, or (F) merged. (G-I) Neuronal-specific expression; (G) β-gal-IR, (H) NeuN-IR, or (I) merged. Arrows indicate costained cells, and arrowheads show cells that contained only β-gal-IR. Scale bars: (A-F) 50 μm; (G-I) 100 μm.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of cells that contained β-gal-IR, and the types of transduced cells, in rats sacrificed at 4 days after injection of pVGLUT1lac into POR cortex

| Cell marker | β-gal-IR cells | Costained cellsa | % costained |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAG | 314 | 287 | 92 |

| GAD | 212 | 23 | 11 |

| NeuN | 207 | 200 | 97 |

The titers of pVGLUT1lac are in Table 1. Gene transfer conditions were as in Table 2. Three hemispheres were analyzed, and 3-6 sections were analyzed in each hemisphere. All the β-gal-IR cells in each section that was examined were scored for costaining with the appropriate cell marker.

Costained cells are positive for both β-gal-IR and the cell marker-IR.

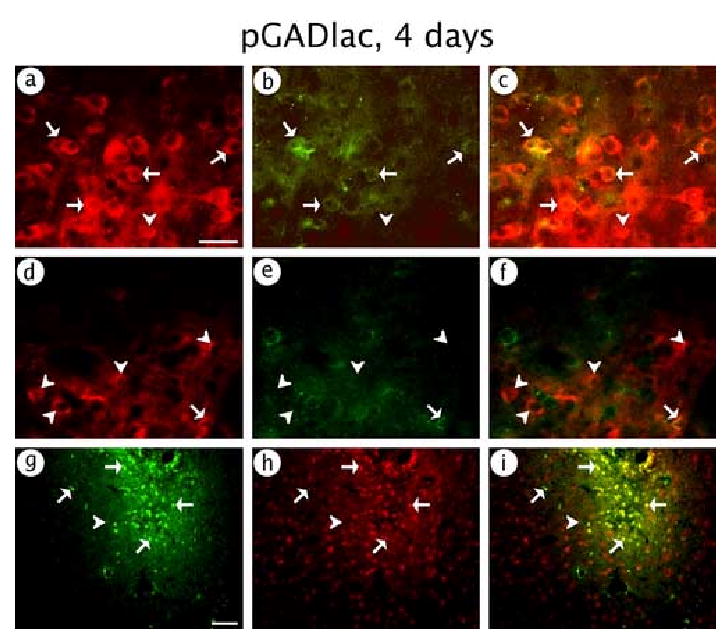

pGADlac supported expression in GABAergic neurons, as revealed by a high level of costaining for β-gal-IR and GAD-IR (Fig. 5A-C); nonetheless, a few β-gal-IR cells lacked GAD-IR. In contrast, pGADlac supported only low levels of expression in glutamatergic neurons, as shown by costaining for β-gal-IR and PAG-IR (Fig. 5D-F). Consistent with GABAergic neuron-specific expression, virtually all of the expression was in neurons, as shown by costaining for β-gal-IR and NeuN-IR (Fig. 5G-I). Cell counts (Table 4) showed that 88 % of the expression was in GABAergic neurons, whereas only 13 % of the expression was in glutamatergic neurons. The sum of the counts of expression in glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons (88 % + 13 % = 101 %) showed that virtually all of the expression was in GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons, consistent with 96 % neuronal-specific expression from counts of the NeuN-IR costaining (Table 4). Because the assays for glutamatergic neurons and GABAergic neurons use different antibodies with different sensitivities, the sum of the counts of these two types of neurons (101 %) was slightly over 100 %.

Fig. 5.

pGADlac supported expression of β-gal predominantly in GABAergic neurons. The rat was sacrificed at 4 days after gene transfer. (A-C) GABAergic neuron-specific expression; (A) β-gal-IR, (B) GAD-IR, or (C) merged. (D-F) Glutamatergic neuron-specific expression; (D) β-gal-IR, (E) PAG-IR, or (F) merged. (G-I) Neuronal-specific expression; (G) β-gal-IR, (H) NeuN-IR, or (I) merged. Arrows indicate costained cells, and arrowheads show cells that contained only β-gal-IR. Scale bars: (A-F) 50 μm; (G-I) 100 μm.

TABLE 4.

Numbers of cells that contained β-gal-IR, and the types of transduced cells, in rats sacrificed at 4 days after injection of pGADlac into POR cortex

| Cell marker | β-gal-IR cells | Costained cellsa | % costained |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAG | 186 | 25 | 13 |

| GAD | 450 | 394 | 88 |

| NeuN | 235 | 226 | 96 |

The titers of pGADlac are in Table 1. Gene transfer conditions were as in Table 2. Four hemispheres were analyzed, and 3-6 sections were analyzed in each hemisphere. All the β-gal-IR cells in each section that was examined were scored for costaining with the appropriate cell marker.

Costained cells are positive for both β-gal-IR and the cell marker-IR.

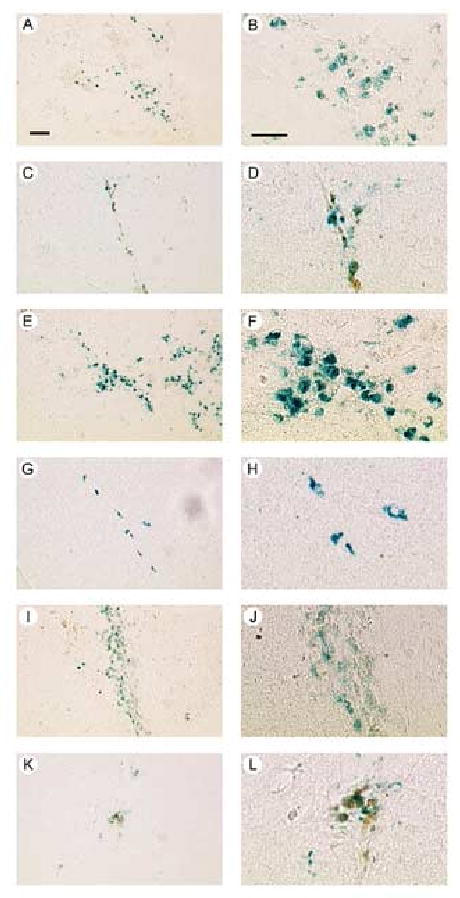

2.3. These vectors supported high levels of long-term (2 months) expression in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons

Stocks of each of the vectors (pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac), or control vectors, were microinjected into POR cortex, and the rats were sacrificed at either 4 days or 2 months after gene transfer. The positive control was pTH-NFHlac, which supports long-term expression, and the negative control was pNFHlac, which supports only short-term expression [59]. Using pPAGlac, a rat sacrificed at 4 days contained numerous X-gal positive cells proximal to the injection site (Fig. 6A), and a high power view (Fig. 6B) showed numerous X-gal positive cell bodies with neuronal morphology (large, non-spherical cell bodies). A rat sacrificed at 2 months contained X-gal positive cells proximal to the injection site (Fig. 6C), but fewer than observed at 4 days, and a high power view (Fig. 6D) showed X-gal positive cell bodies with neuronal morphology. Similar results were obtained using pVGLUT1lac (4 days, Fig. 6E and F; 2 months, Fig. 6G and H) or pGADlac (4 days, Fig. 6I and J; 2 months, Fig. 6K and L). In rats sacrificed at 2 months, the positive control (pTH-NFHlac) supported X-gal positive cells (not shown), but using the negative control (pNFHlac), no X-gal cells were observed (not shown), similar to previous results [57,59].

Fig. 6.

X-gal positive cells from rats sacrificed at either 4 days or 2 months after gene transfer using pPAGlac, or pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac. (A-D) pPAGlac; (A and B) 4 days, or (C and D) 2 months. Low power views (A and C) show numerous X-gal cells proximal to the injection sites, and high power views (B and D) show neuronal morphology, including large cell bodies. (E-H) pVGLUT1lac; (E and F) 4 days, (E) low power, or (F) high power; or (G and H) 2 months, (G) low power, or (H) high power. (I-L) pGADlac; (I and J) 4 days, (I) low power, or (J) high power; or (K and L) 2 months, (K) low power, or (L) high power. Scale bars: (A, C, E, G, I and K) 50 μm; (B, D, F, H, J and L) 30 μm.

Cell counts were used to determine the numbers of expressing cells for each vector and time point. We calculated the % efficiency of gene transfer for each vector (number of X-gal cells at 4 days / titer (IVP) of vector injected × 100). The results (Table 5) showed that pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac supported 2, 5, or 2 % efficiency of gene transfer, respectively. Vectors containing the TH-NFH or INS-TH-NFH promoter supported similar % efficiencies of gene transfer (1-10 %) in specific brain areas [57,59]. Next, we calculated the % stability of long-term expression for each vector (X-gal cells at 2 months / X-gal cells at 4 days × 100). The results (Table 5) showed that pPAGlac and pVGLUT1lac supported similar stabilities of long-term expression, 26 % or 21 %, respectively. pVGLUT1lac appeared to support expression in more cells than pPAGlac, but the difference was significant only at 2 months (4 days p>0.05, 2 months p<0.05, t-test). Of note, pGADlac supported 36 % stability of long-term expression (Table 5). These stabilities of long-term expression compare favorably with the 10 to 20 % stability of long-term expression supported by pTH-NFHlac in the striatum, hippocampus, or neocortex [59].

TABLE 5.

Numbers of X-gal positive cells in rats sacrificed at 4 days or 2 months after injection of pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, pGADlac, or control vectors, into POR cortex

| Average X-gal cells / hemisphere | % efficiency of gene transfera | % long-term expressionb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | 4 days | 2 months | ||

| pPAGlac | 592±190 | 152±12 | 2 % | 26 % |

| pVGLUT1lac | 887±357 | 184±8 | 5 % | 21 % |

| pGADlac | 433±87 | 156±16 | 2 % | 36 % |

| pTH-NFHlac | NDc | 149±31 | ||

| pNFHlac | NDc | 0±0 | ||

The titers of the pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac stocks are in Table 1; the titer of pTH-NFHlac was 9.6 × 106 IVP/ml, and the titer of pNFHlac was 1.5 × 106 IVP/ml. Gene transfer conditions were as in Table 2. Three hemispheres were analyzed for each vector and time point, and every 4th section containing the X-gal positive cells (sections proximal to the injection site) was analyzed. The means±SEMs are shown.

% efficiency of gene transfer = number of X-gal cells at 4 days / titer (IVP) of vector injected × 100.

% long-term expression = number of X-gal cells at 2 months / number of X-gal cells at 4 days × 100.

ND, not done.

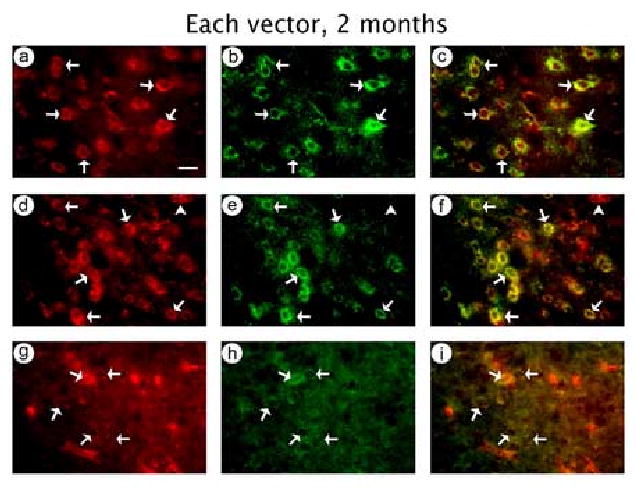

To establish long-term glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression, we performed costaining for β-gal-IR and the appropriate cell marker on sections from rats sacrificed at 2 months after receiving each of the three vectors. Using either pPAGlac or pVGLUT1lac, we observed many cells that costained for β-gal-IR and PAG-IR (pPAGlac, Fig. 7A-C; pVGLUT1lac, Fig. 7D-F). Conversely, using pGADlac, we observed many cells that costained for β-gal-IR and GAD-IR (Fig. 7G-I). Cell counts showed that pPAGlac supported 87 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression at either 2 months (Table 6) or 4 days (Table 2). pVGLUT1lac supported 77 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression at 2 months (Table 6), slightly lower than the 92 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression observed at 4 days (Table 3). pGADlac supported 87 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression at 2 months (Table 6), similar to the 88 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression observed at 4 days (Table 4).

Fig. 7.

In rats sacrificed at 2 months after gene transfer, each of the three vectors supported either glutamatergic neuron-specific or GABAergic neuron-specific expression of β-gal. (A-C) pPAGlac; (A) β-gal-IR, (B) PAG-IR, or (C) merged. (D-F) pVGLUT1lac; (D) β-gal-IR, (E) PAG-IR, or (F) merged. (G-I) pGADlac; (G) β-gal-IR, (H) GAD-IR, or (I) merged. Arrows indicate costained cells, and arrowheads show cells that contained only β-gal-IR. Scale bar: 20 μm.

TABLE 6.

Numbers of cells that contained β-gal-IR, and the types of transduced cells, in rats sacrificed at 2 months after injection of pPAGlac, pVGLUT1lac, or pGADlac, into POR cortex

| Vector | β-gal-IR cells | Costained with PAG-IR | Costained with GAD-IR | % costained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pPAGlac | 247 | 214 | NDa | 87 |

| pVGLUT1lac | 215 | 166 | NDa | 77 |

| pGADlac | 121 | NDa | 105 | 87 |

The titers of the vector stocks are in Table 1. Gene transfer conditions were as in Table 2. For each vector, the sections that were examined were from 3 hemispheres, and 6-8 sections were analyzed in each hemisphere, for each assay. All the β-gal-IR cells in each section that was examined were scored for costaining with the appropriate cell marker.

ND, not done.

3. Discussion

3.1. HSV-1 vectors containing the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters supported glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression

We showed that HSV-1 vectors containing either the rat PAG or mouse VGLUT1 promoter supported ∼90 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression, and a HSV-1 vector containing the mouse GAD67 promoter supported ∼90 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression, in POR cortex. We previously showed that a HSV-1 vector containing a modified neurofilament promoter (INS-TH-NFH promoter) supported approximately equal levels of expression in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons in POR cortex, specifically, 52 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression and 45 % GABAergic neuron-specific expression [58]. Thus, the neuron subtype-specific expression reported here is due to the activity of the specific promoters, and not preferential transduction of a specific neuronal subtype by HSV-1 vector particles. The GABAergic neuron-specific expression supported by pGADlac is consistent with results on the GAD67 promoter in transgenic mice [5,7,15,23,25,30,31,48]. The PAG promoter fragment used here supported kidney cell type-specific expression in a DNA transfection study [49]; however, it remains to be determined if the same, or different, genetic elements confer kidney cell-specific and glutamatergic neuron-specific expression. To our knowledge, there are no previously published studies on the VGLUT1 promoter.

The PAG, VGLUT1, and GAD67 promoters each supported ∼10 % expression in inappropriate cell types. Inappropriate expression is defined as expression from a specific vector in a cell type in which the corresponding endogenous promoter is silent; for example, expression from pVGLUT1lac in GABAergic neurons, as the endogenous VGLUT1 promoter is silent in these cells. Most of this inappropriate expression appeared to be in other types of neurons, although costaining with glial-specific markers was not performed. Some of this inappropriate expression may be due to side effects of the vector system (any cytotoxicity or immune response); consistent with this view, the same vector containing a TH promoter supported 40 % catecholaminergic neuron-specific expression using a helper virus-containing system [38], but ∼61 % catecholaminergic neuron-specific expression using the helper virus-free system [55], which causes markedly less cytotoxicity or immune response [11,32]. Thus, although the helper virus-free system causes few side effects, any side effects it does cause may contribute to the inappropriate expression. Alternatively, this inappropriate expression could be due to genetic regulatory events that occur during the differentiation of neurons, and are not reproduced when HSV-1 vectors deliver these promoters into mature neurons. For example, at a specific time during development, a specific DNA sequence may be demethylated as part of the mechanism that initiates transcription from that promoter, and this event will not occur following introduction of a vector into a mature neuron. Or, each promoter fragment used here may lack specific modulatory genetic regulatory elements that assist in conferring high levels of neuronal subtype-specific expression; for example, pVGLUT1lac supported ∼90 % glutamatergic neuron-specific expression, and this vector may lack specific modulatory elements in the endogenous VGLUT1 promoter that enable this endogenous promoter to support expression in glutamatergic neurons, with no expression in inappropriate cell types.

Glutamatergic and GABAergic neuron subtypes each contain multiple classes of neurons [28,29,41], and specific classes are preferentially located in specific cortical layers. Our injection coordinates were located deep in POR cortex, and most of the transduced neurons were located deep in POR cortex, although we did not determine the distribution of transduced neurons among the different cortical layers. Thus, we did not determine if the promoters studied here supported expression in most classes of either glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons. However, it seems unlikely that the high levels of % glutamatergic or GABAergic neuron-specific expression, and the high efficiencies of gene transfer, observed here are consistent with activity in only a small subset of the classes of either glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons. Moreover, the GAD67 promoter fragment used here supports expression in most classes of GABAergic neurons in transgenic mice, while shorter fragments of the GAD67 promoter show more restricted expression in transgenic mice [5,7,15,23,25,30,31,48]. PAG produces the majority of the neurotransmitter glutamate and is thought to be present in most glutamatergic neurons [20,21,27,35,50], consistent with our results. VGLUT1 is the predominant VGLUT in the neocortex [3,12,13,17,46,47,51], consistent with our results. VGLUT2 is found in some neurons in cortical layer 4. However, the level of analysis used here was unlikely to discern the presence, or lack, of β-gal-IR cells in a subset of neurons within a narrow band, such as layer 4. Moreover, POR cortex contains a different set of layers compared to much of neocortex; posterior or anterior POR cortex contains 3 or 4 layers, respectively [4], and the distributions of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in POR cortex have not been precisely determined.

HSV-1 vectors might be used to identify the critical elements in the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters that confer neuronal subtype-specific expression. A deletion analysis of the 6.0 kb TH promoter fragment in the TH-NFH promoter identified two ∼100 bp fragments with enhancer activity within an ∼320 bp fragment [14]. A deletion analysis of the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters might determine if one element supports expression in all the classes of glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, or if different elements support expression in specific classes. Such deletion analyses are difficult to perform in transgenic mice due to time and cost, and AAV or lentivirus vectors lack the capacity to contain the large promoter fragments used here.

3.2. HSV-1 vectors containing specific promoters support long-term expression in neurons, or specific types of neurons

The PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters supported a % of long-term expression that compares favorably with the TH-NFH promoter [59]; however, the numbers of positive cells at 2 months were modest, ∼150 X-gal cells (Table 5). In contrast, using the INS-TH-NFH promoter, we obtained ∼11,400 expressing cells (in the striatum) at 6 months after gene transfer [42]. This other study [42] used three injection sites, compared to the one site used here, and the vector titers were ∼3-fold higher than those used here (and studied a different brain region). Also, this other study used the INS-TH-NFH promoter which is active in most neurons, whereas each of the promoters used here is active in ∼50 % of the neurons. Together, this 18-fold difference accounts for most the difference between the numbers of positive cells observed here and in the study that reported ∼11,400 expressing cells at 6 months [42].

Addition of the INS to the TH-NFH promoter increased the stability of long-term expression from 10 - 20 % to 30 - 40 % [59]. Analogously, addition of the INS to the PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters might further increase the stability of long-term expression supported by each promoter. Nonetheless, the 26, 21, or 36 % stabilities of long-term expression supported by PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters, respectively, are already comparable to the 30 to 40 % stability of long-term expression supported by the INS-TH-NFH promoter [59]. Of note, the INS-TH-NFH promoter has supported physiological studies with long-term changes in neuronal physiology, behavior, and learning [42-44,58].

Although initial attempts at identifying promoters that support long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors were problematic, there is now a list of five promoters that support long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors, namely the TH [18,38], preproENK [22], PAG, VGLUT1, or GAD67 promoters. Interestingly, each of these five promoters supports expression in a specific subtype of neurons. Of note, the proteins encoded by these five genes have diverse functions; TH, PAG, and GAD are classical neurotransmitter biosynthetic enzymes; ENK is a peptide neurotransmitter, and VGLUT1 is a vesicular transporter. This diversity of function suggests that other promoters that are active in a specific type of neuron will also support long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors. In contrast, a number of herpesvirus, and other viral, promoters support little or no long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors (reviewed in [59]). These viral promoters may be shut off by mechanisms similar to those that shut off most HSV-1 gene expression as HSV-1 enters the latent state [34,39,40]. Also, a number of neuronal-specific promoters support minimal long-term expression from HSV-1 vectors, including the NF-H, neuron-specific enolase, and voltage-gated sodium channel promoters [55]. Many neuronal-specific promoters, including the NF-H promoter, contain the neuronal silencer element (REST) [6,36,37]; REST is expressed in virtually all non-neuronal cells. Thus, these neuronal-specific promoters are passively turned on in neurons, which lack REST. In HSV-1 vectors, this passive induction may render these promoters vulnerable to the mechanisms that shut off most HSV-1 gene expression as HSV-1 enters the latent state [34,39,40]. These observations suggested that addition of specific enhancers from neuronal subtype-specific promoters would enable long-term expression from REST-regulated, neuronal-specific promoters. Three chimeric promoters support this hypothesis; the TH-NFH [14,59], INS-TH-NFH [59], and ENK-NFH [53] promoters each support long-term expression in forebrain neurons.

Thus, HSV-1 vectors containing neuronal subtype-specific promoters can support long-term expression in specific types of neurons. In particular, expressing specific genes that affect neuronal physiology, in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, may benefit gene therapy or basic neuroscience studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

OptiMEM, penicillin/streptomycin, Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium (DMEM), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Invitrogen. G418 was obtained from RPI. Restriction endonucleases and DNA modifying enzymes were from New England Biolabs. PCR primers, PCR reagents, and the TOPO TA cloning kit were obtained from Invitrogen. X-gal was obtained from Sigma. Rabbit anti-E. coli β-gal, rabbit anti-GAD, and mouse anti-NeuN antibodies were obtained from Chemicon. Mouse anti-E. coli β-gal, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were obtained from Sigma. Prepacked diethylaminoethyl/Affi-Gel blue column was from Biorad.

4.2. Cells

BHK21 and 2-2 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS, 4 mM glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin. They were grown in an incubator at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 and 100 % humidity. G418 (0.5 mg/ml), present during the growth of 2-2 cells, was removed before plating cells for vector packaging.

4.3. Vectors

The starting point for the vector constructions was pTH-NFHlac [59]; the TH-NFH promoter fragment was excised (BamH I partial, Hind III complete reaction), and was replaced by a polylinker to yield pLinker-lac. The polylinker sequence was: sense, 5′ CTCGAGGGATCCCTTAAGACTGTAGCGGCCGCGGCCGGCCGTTTAAACGGCGCGCCAAGCTT 3′ and antisense, 5′AAGCTTGGCGCGCCGTTTAAACGGCCGGCCGCGGCCGCTACAGTCTTAAGGGATCCCTCGA 3′, the polylinker contains sites for Xho I, BamH I, Afl II, Not I, Fse I, Pme I, Asc I, Hind III, and includes a 6 bp spacer between the Afl II and Not I sites.

A 2.4 kb fragment containing the rat PAG promoter (pλGA1 [49]) was isolated by PCR. Primers were designed to introduce a Not I site at the 5′ end and an Asc I site at the 3′ end; sense, 5′ GCGGCCGCCCTCTACCCACTGAGCCATG 3′ (nucleotides 1 - 20) and antisense, 5′ GGCGCGCCGCCGCCGGCGCCCGCTCGTCAGAAGAGGATGC 3′ (antisense to nucleotides 2,390 – 2,422). The PCR product was digested with Not I and Asc I, and inserted into pLinker-lac that had been digested with the same enzymes, to yield pPAGlac.

pVGLUT1lac was designed to contain the mouse VGLUT1 promoter and first intron (p7-13 and p7-14 [56], gifts from Drs. N. Brose and C. Rosenmund). The first intron may have a role in VGLUT1 transcription control (Personal communication from Dr. Herzog). The VGLUT1 promoter was isolated from p7-14 as a 7 kb Not I fragment and inserted into pLinker-lac that had been digested with Not I, to yield pVGLUT1-prom-lac. The splice donor and acceptor sites for the VGLUT1 first intron were isolated as two PCR fragments; one PCR fragment contained the splice donor site, and the other PCR fragment contained the splice acceptor site. The template for PCR was p7-13; primers for the first PCR fragment were: sense, 5′ GGATCCGGCCGGCCCCGGTGAGCCTGGTGGGGTTCCTGG 3′ (nucleotides 118 to 142; contains BamH I and Fse I sites); and antisense, 5′ CTATAGGTGTGAGTGTAACCCCTGA 3′ (antisense to nucleotides 2,322 - 2,343). The primers for the second PCR fragment were: sense, 5′ TGTATGAGACTCAGAATCCTGTTTG 3′ (nucleotides 2,236 – 2,260); and antisense, 5′ GGTACCGGCGCGCCCTGCAGGGAAGCGAGAAGCAAAGAC 3′ (antisense to nucleotides 4,689 – 4,713; contains Kpn I and Asc I sites). The two PCR fragments were cloned into TOPO vectors. Both PCR fragments contained an internal Hind III site. The first PCR fragment was excised from the TOPO vector with BamH I and Hind III, the second PCR fragment was excised with Hind III and Kpn I, and the two fragments were inserted into pUC19 that had been digested with BamH I and Kpn I, to yield pVGLUT1intron. The intron was excised from pVGLUT1intron by digestion with Fse I and Asc I and inserted into pVGLUT1-prom-lac that had been digested with the same enzymes, to yield pVGLUT1lac, which contains an 11.6 kb fragment of the VGLUT1 promoter and first intron.

A 10.1 kb fragment containing the mouse GAD67 promoter (derived from pGAD67-lacZ [23], gift from Dr. Y. Yanagawa) was inserted into pLinker-lac in two steps. First, a 3.1 kb fragment containing the 3′ part of the promoter (and 1.4 kb of the Lac Z gene) was obtained by digestion of pGAD67-lacZ with Not I and EcoR V, and inserted into pLinker-lac that had been digested with the same enzymes, to yield pGAD3′-lac. Next, pGAD67-lacZ was digested with Hind III, treated with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and then digested with Not I (yielding an 8.4 kb fragment of upstream GAD67 promoter sequences); pGAD3′-lac was digested with Afl II, treated with the Klenow enzyme, and then digested with Not I; these two fragments each contain a Not I end and a blunt end, and they were ligated to yield pGADlac.

4.4. Packaging

The vectors were packaged into HSV-1 particles using a modified form of the helper-virus free packaging protocol described previously [11,45]. Purified vectors were titered on BHK cells, by counting X-gal positive cells at 24 hrs post-transduction. Vector genome titers were determined by performing PCR on DNA extracted from the purified vector stocks, using primers for the Lac Z gene [57]. Wild-type HSV-1 was not detected (<10 plaque forming units/ml) in any of the vector stocks.

4.5. Stereotactic injections of vectors into rat POR cortex

The W. Roxbury VA Hospital IACUC approved all the animal procedures. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300 g) were anesthetized by ip injection of a Ketamine (20 mg/ml) Xylazine (2 mg/ml) mixture with a final dose of 60 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg, respectively. Additional anesthesia was administered as needed. Each rat received 2 injections into POR cortex, one in each hemisphere: The injection coordinates were anteroposterior (AP) -7.8 – -8.0 mm, mediolateral (ML): ±5.8 – 6.0 mm and dorsoventral (DV): (-5.6) – (-6.0) mm [33]. AP is measured relative to bregma, ML is relative to the sagittal suture and DV is relative to the bregma-lambda plane. The coordinates are given as intervals to allow for individual variation in rat size. A micropump (model 100, KD Scientific) was used for the injections, 3 μl of vector stock was injected at each site over 5 minutes, and after 5 additional minutes, the needle was slowly retracted.

4.6. Immunohistochemistry

Brains were perfused as described [59], and 25 μm coronal sections containing, or proximal to, the injection site were prepared using a freezing microtome. X-gal staining was performed as described [59]. Mouse anti-PAG antibody was purified using a prepacked diethylaminoethyl/Affi-Gel blue column, following the manufacturer's instructions. Immunohistochemistry was performed on free-floating sections as described [59]. β-gal-IR was detected using either rabbit or mouse anti-β-gal antibody (1:1,000 dilution or 1:200 dilution, respectively). Cell types were identified using rabbit anti-GAD (1:5,000 dilution), or rabbit anti-PAG (1:150 dilution), or mouse anti-NeuN (1:200 dilution). Primary antibodies were visualized with either TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG.

4.7. Cell counts

Neuronal subtype-specific or neuronal-specific expression was quantified by cell counts. Digital images were taken at 20× or 60× magnification, merged using image manipulation software (GNU image manipulation program, www.gimp.org), and counts were performed on these merged images. In the fields that were examined, all the β-gal-IR cells were scored for containing, or lacking, a specific cell marker. X-gal positive cells were counted from digital images taken at 60× magnification. All counts were done at least two separate times, and results differed by <10 %.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Drs. N. Brose and C. Rosenmund (Max Planck-Institute, Gottingen Germany) for the VGLUT1 promoter, Dr. Y. Yanagawa (Gunma Univ., Maebashi Japan) for the GAD67 promoter, Dr. K. O'Malley (Univ. Wash., St. Louis MO) for the TH promoter, Dr. W. Schlaepfer (Univ. PA, Philadelphia PA) for the NFH promoter, Dr. A. Davison (Institute of Virology, Glasgow UK) for HSV-1 cosmid set C, and Dr. R. Sandri-Goldin (Univ. CA, Irvine CA) for 2-2 cells. This work was supported by The Denmark-America Foundation (MR), and AG16777, NS043107, NS045855, and AG021193 (AG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bali B, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, Kovacs KJ. Visualization of stress-responsive inhibitory circuits in the GAD65-eGFP transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banner C, Hwang JJ, Shapiro RA, Wenthold RJ, Nakatani Y, Lampel KA, Thomas JW, Huie D, Curthoys NP. Isolation of a cDNA for rat brain glutaminase. Brain Res. 1988;427:247–54. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–60. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burwell RD. Borders and cytoarchitecture of the perirhinal and postrhinal cortices in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:17–41. doi: 10.1002/cne.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyaya B, Di Cristo G, Higashiyama H, Knott GW, Kuhlman SJ, Welker E, Huang ZJ. Experience and activity-dependent maturation of perisomatic GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex during a postnatal critical period. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9598–611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1851-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong JA, Tapia-Ramirez J, Kim S, Toledo-Aral JJ, Zheng Y, Boutros MC, Altshuller YM, Frohman MA, Kraner SD, Mandel G. REST: a mammalian silencer protein that restricts sodium channel gene expression to neurons. Cell. 1995;80:949–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Cristo G, Wu C, Chattopadhyaya B, Ango F, Knott G, Welker E, Svoboda K, Huang ZJ. Subcellular domain-restricted GABAergic innervation in primary visual cortex in the absence of sensory and thalamic inputs. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1184–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erlander MG, Tillakaratne NJ, Feldblum S, Patel N, Tobin AJ. Two genes encode distinct glutamate decarboxylases. Neuron. 1991;7:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90077-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esclapez M, Tillakaratne NJ, Kaufman DL, Tobin AJ, Houser CR. Comparative localization of two forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase and their mRNAs in rat brain supports the concept of functional differences between the forms. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1834–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldblum S, Erlander MG, Tobin AJ. Different distributions of GAD65 and GAD67 mRNAs suggest that the two glutamate decarboxylases play distinctive functional roles. J Neurosci Res. 1993;34:689–706. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraefel C, Song S, Lim F, Lang P, Yu L, Wang Y, Wild P, Geller AI. Helper virus-free transfer of herpes simplex virus type 1 plasmid vectors into neural cells. J Virol. 1996;70:7190–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7190-7197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fremeau RT, Jr, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:247–60. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fremeau RT, Jr, Voglmaier S, Seal RP, Edwards RH. VGLUTs define subsets of excitatory neurons and suggest novel roles for glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Q, Sun M, Wang X, Geller AI. Isolation of an enhancer from the rat tyrosine hydroxylase promoter that supports long-term, neuronal-specific expression from a neurofilament promoter, in a helper virus-free HSV-1 vector system. Brain Res. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.018. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, Wunderbaldinger G, Sandkuhler J. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurones identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:249–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertz L. Intercellular metabolic compartmentation in the brain: past, present and future. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin BK, Belloni M, Conti B, Federoff HJ, Starr R, Son JH, Baker H, Joh TH. Prolonged in vivo gene expression driven by a tyrosine hydroxylase promoter in a defective herpes simplex virus amplicon vector. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:2015–24. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.16-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Mathers PH, Szabo G, Katarova Z, Agmon A. Vertical bias in dendritic trees of non-pyramidal neocortical neurons expressing GAD67-GFP in vitro. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:666–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko T, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical study of glutaminase-containing neurons in the cerebral cortex and thalamus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;267:590–602. doi: 10.1002/cne.902670411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko T, Nakaya Y, Mizuno N. Paucity of glutaminase-immunoreactive nonpyramidal neurons in the rat cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1992;322:181–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplitt MG, Kwong AD, Kleopoulos SP, Mobbs CV, Rabkin SD, Pfaff DW. Preproenkephalin promoter yields region-specific and long-term expression in adult brain after direct in vivo gene transfer via a defective herpes simplex viral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8979–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi T, Ebihara S, Ishii K, Nishijima M, Endo S, Takaku A, Sakagami H, Kondo H, Tashiro F, Miyazaki J, Obata K, Tamura S, Yanagawa Y. Structural and functional characterization of mouse glutamate decarboxylase 67 gene promoter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1628:156–68. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(03)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Bendito G, Sturgess K, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, Molnar Z, Paulsen O. Preferential origin and layer destination of GAD65-GFP cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1122–33. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y, Hu H, Berrebi AS, Mathers PH, Agmon A. Distinct subtypes of somatostatin-containing neocortical interneurons revealed in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5069–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0661-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makinae K, Kobayashi T, Shinkawa H, Sakagami H, Kondo H, Tashiro F, Miyazaki J, Obata K, Tamura S, Yanagawa Y. Structure of the mouse glutamate decarboxylase 65 gene and its promoter: preferential expression of its promoter in the GABAergic neurons of transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1429–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masson J, Darmon M, Conjard A, Chuhma N, Ropert N, Thoby-Brisson M, Foutz AS, Parrot S, Miller GM, Jorisch R, Polan J, Hamon M, Hen R, Rayport S. Mice lacking brain/kidney phosphate-activated glutaminase have impaired glutamatergic synaptic transmission, altered breathing, disorganized goal-directed behavior and die shortly after birth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4660–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4241-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mott DD, Dingledine R. Interneuron Diversity series: Interneuron research--challenges and strategies. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:484–8. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson SB, Sugino K, Hempel CM. The problem of neuronal cell types: a physiological genomics approach. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliva AA, Jr, Jiang M, Lam T, Smith KL, Swann JW. Novel hippocampal interneuronal subtypes identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein in GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3354–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03354.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliva AA, Jr, Lam TT, Swann JW. Distally directed dendrotoxicity induced by kainic Acid in hippocampal interneurons of green fluorescent protein-expressing transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8052–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olschowka JA, Bowers WJ, Hurley SD, Mastrangelo MA, Federoff HJ. Helper-free HSV-1 amplicons elicit a markedly less robust innate immune response in the CNS. Mol Ther. 2003;7:218–27. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(02)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2. Sydney: Academic; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roizman B, Sears AE. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In: Roizman B, Whitley RJ, Lopez C, editors. The human herpesviruses. Raven Press; New York: 1993. pp. 11–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakata S, Kitsukawa T, Kaneko T, Yamamori T, Sakurai Y. Task-dependent and cell-type-specific Fos enhancement in rat sensory cortices during audio-visual discrimination. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:735–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenherr CJ, Anderson DJ. The neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF): a coordinate repressor of multiple neuron-specific genes. Science. 1995;267:1360–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7871435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoenherr CJ, Paquette AJ, Anderson DJ. Identification of potential target genes for the neuron-restrictive silencer factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9881–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song S, Wang Y, Bak SY, Lang P, Ullrey D, Neve RL, O'Malley KL, Geller AI. An HSV-1 vector containing the rat tyrosine hydroxylase promoter enhances both long-term and cell type-specific expression in the midbrain. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1792–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68051792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens JG. Latent herpes simplex virus and the nervous system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1975;70:31–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66101-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens JG, Wagner EK, Devi-Rao GB, Cook ML, Feldman LT. RNA complementary to a herpesvirus alpha gene mRNA is prominent in latently infected neurons. Science. 1987;235:1056–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2434993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugino K, Hempel CM, Miller MN, Hattox AM, Shapiro P, Wu C, Huang ZJ, Nelson SB. Molecular taxonomy of major neuronal classes in the adult mouse forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:99–107. doi: 10.1038/nn1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun M, Kong L, Wang X, Holmes C, Gao Q, Zhang W, Pfeilschifter J, Goldstein DS, Geller AI. Coexpression of Tyrosine Hydroxylase, GTP Cyclohydrolase I, Aromatic Amino Acid Decarboxylase, and Vesicular Monoamine Transporter-2 from a Helper Virus-Free HSV-1 Vector Supports High-Level, Long-Term Biochemical and Behavioral Correction of a Rat Model of Parkinson's Disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:1177–1196. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun M, Kong L, Wang X, Lu X, Gao Q, Geller AI. Comparison of protection of nigrostriatal neurons by expression of GDNF, BDNF, or both neurotrophic factors. Brain Res. 2005;1052:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun M, Zhang G, Kong L, Holmes C, Wang X, Zhang W, Goldstein DS, Geller AI. Correction of a rat model of Parkinson's disease by coexpression of tyrosine hydroxylase and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase from a helper virus-free herpes simplex virus type 1 vector. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:415–24. doi: 10.1089/104303403321467180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun M, Zhang GR, Yang T, Yu L, Geller AI. Improved titers for helper virus-free herpes simplex virus type 1 plasmid vectors by optimization of the packaging protocol and addition of noninfectious herpes simplex virus-related particles (previral DNA replication enveloped particles) to the packaging procedure. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2005–11. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature. 2000;407:189–94. doi: 10.1038/35025070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of differentiation-associated brain-specific phosphate transporter as a second vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT2) J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamamaki N, Yanagawa Y, Tomioka R, Miyazaki J, Obata K, Kaneko T. Green fluorescent protein expression and colocalization with calretinin, parvalbumin, and somatostatin in the GAD67-GFP knock-in mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:60–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor L, Liu X, Newsome W, Shapiro RA, Srinivasan M, Curthoys NP. Isolation and characterization of the promoter region of the rat kidney-type glutaminase gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1518:132–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van der Gucht E, Jacobs S, Kaneko T, Vandesande F, Arckens L. Distribution and morphological characterization of phosphate-activated glutaminase-immunoreactive neurons in cat visual cortex. Brain Res. 2003;988:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varoqui H, Schafer MK, Zhu H, Weihe E, Erickson JD. Identification of the differentiation-associated Na+/PI transporter as a novel vesicular glutamate transporter expressed in a distinct set of glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:142–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wade-Martins R, Saeki Y, Chiocca EA. Infectious delivery of a 135-kb LDLR genomic locus leads to regulated complementation of low-density lipoprotein receptor deficiency in human cells. Mol Ther. 2003;7:604–12. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Kong L, Zhang G, Sun M, Geller AI. A preproenkephalin-neurofilament chimeric promoter enhances long-term expression in the rat brain from helper virus-free HSV-1 vectors. Neurobiol of Disease. 2004;16:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Zhang G, Yang T, Zhang W, Geller AI. Fifty-one kilobase HSV-1 plasmid vector can be packaged using a helper virus-free system and supports expression in the rat brain. BioTechniques. 2000;27:102–6. doi: 10.2144/00281st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Yu L, Geller AI. Diverse stabilities of expression in the rat brain from different cellular promoters in a helper virus-free herpes simplex virus type 1 vector system. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1763–71. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wojcik SM, Rhee JS, Herzog E, Sigler A, Jahn R, Takamori S, Brose N, Rosenmund C. An essential role for vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1) in postnatal development and control of quantal size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7158–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401764101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang T, Zhang G, Zhang W, Sun M, Wang X, Geller AI. Enhanced reporter gene expression in the rat brain from helper virus-free HSV-1 vectors packaged in the presence of specific mutated HSV-1 proteins that affect the virion. Molec Brain Res. 2001;90:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang G, Wang X, Kong L, Lu X, Lee B, Liu M, Sun M, Franklin C, Cook RG, Geller AI. Genetic enhancement of visual learning by activation of protein kinase C pathways in small groups of rat cortical neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:8468–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2271-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang G, Wang X, Yang T, Sun M, Zhang W, Wang Y, Geller AI. A tyrosine hydroxylase--neurofilament chimeric promoter enhances long-term expression in rat forebrain neurons from helper virus-free HSV-1 vectors. Molec Brain Res. 2000;84:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]