Abstract

Objective

Given the risk for adolescent depression in girls to lead to a chronic course of mental illness, prevention of initial onset could have a large impact on reducing chronicity. If symptoms of depression that emerge during childhood were stable and predictive of later depressive disorders and impairment, then secondary prevention of initial onset of depressive disorders would be possible.

Method

Drawing from the Pittsburgh Girls Study, an existing longitudinal study, 232 nine-year-old girls were recruited for the present study, half of whom screened high on a measure of depression at age 8 years. Girls were interviewed about depressive symptoms using a diagnostic interview at ages 9, 10, and 11 years. Caregivers and interviewers rated impairment in each year.

Results

The stability coefficients for DSM-IV symptom counts for a 1- to 2-year interval were in the moderate range (i.e., intraclass coefficients of 0.40–0.59 for continuous symptom counts and Kendall τ-b coefficients of 0.34–0.39 for symptom level stability). Depressive disorders were also relatively stable at this age. Poverty moderated the stability, but race and pubertal stage did not. Among the girls who did not meet criteria for a depressive disorder at age 9 years, the odds of meeting criteria for depressive disorders and for demonstrating impairment at age 10 or 11 years increased by 1.9 and 1.7, respectively, for every increase in the number of depression symptoms.

Conclusions

Early-emerging symptoms of depression in girls are stable and predictive of depressive disorders and impairment. The results suggest that secondary prevention of depression in girls may be accomplished by targeting subthreshold symptoms manifest during childhood.

Keywords: girls, childhood, depression, DSM-IV, prediction

Depressive disorders are one of the most common mental disorders among adolescents. Prevalence of depression increases dramatically from 1% in childhood to 8% in adolescents, with a lifetime prevalence in adolescents of 15% to 20%, which is comparable to that found in adults.1 It is primarily girls who account for the increase in adolescence,2,3 evidencing a 2:1 sex difference in depression that continues throughout the reproductive years.4 Initial episodes of depression are more severe and longer in duration for girls than for boys,5 and girls who experience depression for the first time in childhood or adolescence, compared with females with onsets later in life, have a prolonged period of risk for future episodes.6 Depressive disorders continue to be among the most common disorders for females later in life and are cited as the leading cause of disability in 15- to 44-year-old women.7 Thus, predicting and ultimately preventing depression in females is of enormous public health significance.

Typically, the best predictor of later psychopathology, including depression, is earlier psychopathology.8 Kovacs and coworkers have shown that childhood-onset depression is likely to recur in adolescence in 40% to 60% of clinically referred cases.9 Major depressive disorder, however, is too uncommon in childhood to be useful as a predictor of later disorder. Moreover, from a prevention perspective, it would be highly useful to predict the initial onset of disorder, rather than recurrence. In keeping with the assumption that the best predictor of later psychopathology is earlier psychopathology, the predictive validity of symptoms of depression during childhood to depressive disorders would be a logical hypothesis to test. To date, however, the stability and predictive validity of childhood symptoms to later depressive disorders has been examined in a limited way.

For example, there is evidence of the predictive validity of depression scores on various self-report measures in nonclinical samples. A recent review revealed that children’s scores on depression-screening questionnaires are moderately or highly stable across time frames (e.g., 1–72 months) and across sexes, although stability coefficients were somewhat higher for girls than for boys in a number of studies.10 In most studies, however, nondiagnostic questionnaires were used, and in most samples, children scoring in the clinically significant range were underrepresented. Stability in such biased samples can be highly influenced by people who score in the zero to low range at both time points. The possibility that high stability of depression scores in these contexts cannot be equated with stability or predictive validity of childhood symptoms of depression, given the low rates of depression in most samples, has been raised.10 Thus, there is a need for replication in nonclinical samples with sufficient levels of depression and with methods that include diagnostic measures to complement existing studies.10

A few more clinically relevant studies have been conducted, but the results raise more questions about the predictive validity of DSM-based symptoms in children. In the Dunedin Longitudinal Study, a continuous measure of DSM-III-R symptoms of depression at age 9 years assessed via an unstructured clinical interview by a psychiatrist did not differentiate persons with and without a major depressive disorder in late adolescence or adulthood.11,12 Sex effects were not tested in the Dunedin Study.

In the Great Smoky Mountains Study, a structured psychiatric interview was administered to the youths and caregiver to assess major depression, minor depression, and dysthymia at ages 9 to 13 years.8 The odds of girls manifesting any of the three depressive disorders in any subsequent annual assessment through the age of 16 years, given the presence of a depressive disorder at ages 9 to 13 years, was 20.1.8 This risk was significantly greater than that observed for boys, for whom the odds ratio was 5.2.8 Thus, in two separate population-based studies, evidence for and against the predictive validity of childhood depression is provided.

Three significant differences between these two studies may explain the discrepant results: the use of a structured versus an unstructured assessment of DSM-based depressive symptoms, the use of symptom counts versus depressive disorders, and the use of a single (i.e., 9 years old) versus an extended age range (i.e., 9–13 years old). The lack of a structured method of assessment in the Dunedin Study may have influenced the reliability of those symptoms, leading to an underestimate of the predictive validity. The results from the Great Smoky Mountains Study are impressive with respect to the predictive validity of childhood depressive disorders in girls. The fact that the age range included the early adolescent period, however, makes it difficult to argue that depressive disorders in childhood demonstrate sufficient predictive validity. Moreover, for preventive purposes, the predictive validity of symptoms to disorders needs to be tested in addition to the predictive validity of disorders.

If childhood symptoms of depression in girls are predictive of disorders and impairment, then treatment of symptoms and subsyndromal forms of depression in preadolescence may be one of the few options for reducing the chronicity of depression. The present study is designed to provide data that will address this critical issue for women’s mental health. We accomplish this goal by assessing DSM-IV symptoms of depression and depressive disorders (i.e., minor and major depressive disorders) in girls using a diagnostic interview across a three-year period from ages 9 to 11 years. This is an important developmental period within which to test stability and predictive validity of symptoms. Age of 9 years is the earliest age for which reliability of the assessment of DSM symptoms is available.13 The period from 9 to 11 years, which we refer to as late childhood, precedes the increase in depression in females. It therefore has the potential to serve as a window of vulnerability for the development of depression and a prime period for secondary prevention. We include minor depression in the present study because of its demonstrated similarity with major depression in current level of functional impairment,14 future need for service use and risk for subsequent major depressive episodes,15 and family-genetic risk.16 Data that further support the clinical validity of minor depression also are provided in the present study.

In addition, we examine the effect of pubertal stage, race, or poverty on the stability and predictive validity of depressive symptoms in late childhood. The role of pubertal development in the onset of depression in girls still remains unclear. A main effect of pubertal development on depression has not been found consistently.17,18 Greater empirical support is seen for an association between pubertal timing (relative to peers) and depression.19,20 Even in this literature, however, the association between early developing puberty and higher depression scores is complex, with differences in depression scores emerging over time, not at the time of pubertal onset (often operationalized as age at menarche).21 The level of complexity in the puberty–depression literature is further increased by the possibility that both pubertal development and depression may be associated with a shared factor, such as race or living in an economically stressed environment. Both race and poverty, which are often confounded within studies, are associated with heightened risk for depression.22–24 In the present study, we examine whether there is a unique contribution of pubertal stage, race, and poverty to the predictive validity of depressive symptoms and disorders in late childhood in girls.

METHOD

Sampling of Participants

Participants are girls and their biological mothers recruited from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS),25 for which a stratified random household sampling, with oversampling of households in low-income neighborhoods, was used to identify girls who were between the ages of 5 and 8 years. Neighborhoods in which at least 25% of the families were living at or below the poverty level were fully enumerated (i.e., all homes were contacted to determine if the household contained an eligible girl), and a random selection of 50% of the households in the remaining neighborhoods were enumerated during 1998 and 1999. The enumeration identified 3,118 separate households in which an eligible girl resided. From these households, families who moved out of state and families in which the girl would be age ineligible by the start of the study were excluded. When two age-eligible girls were enumerated in a single household, one girl was randomly selected for participation. Of the 2,992 eligible families, 2,875 (96%) were successfully recontacted to determine their willingness to participate in the longitudinal study, and 85% of those families agreed to participate, resulting in a sample of 2,451.

Girls selected for participation in the Emotions substudy (PGS-E) were from the youngest participants in the PGS who either screened high on measures of depressive symptoms by their self-report and parent report at age 8 years or were included in a random selection from the remaining girls. The oversampling was designed to increase the base rate of depressive symptoms and disorders. Psychometrically sound dimensional screening measures of depression included the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire and the Child Symptom Inventory.26,27 The girls whose scores fell at or above the 75th percentile by their own report on the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire and/or by their mother’s report on the Child Symptom Inventory comprised the screen high group. One hundred thirty-five girls met the screening criteria for falling at or above the 75th percentile. There were significantly more African American girls than European American girls in the screen high group. One hundred thirty-six girls selected from the remainder were matched to the screen high group on race. Eight families were not eligible at the time of recruitment for the PGS-E because the biological mother had died, the family had moved out of Allegheny County, or the family was no longer participating in the main study and could not be contacted. Of the 263 families eligible to participate, 232 (88.2%) agreed to participate and completed the laboratory assessment, 25 (8.3%) refused to participate, and 6 (2.3%) agreed but could not be scheduled for an assessment.

Procedures

At ages 9, 10, and 11 years, the girls and their mothers completed a laboratory assessment during which each informant was interviewed and completed questionnaires. Written informed parental consent and child assent were obtained. The Universities of Pittsburgh and Chicago Institutional Review Boards approved all study procedures. Retention across the three waves was high. At wave 2, 227 (97.8%) completed the assessment, 4 (1.7%) declined to participate, and 1 (0.4%) could not be scheduled. At wave 3, 225 (97.0%) completed the assessment, 5 (2.2%) declined to participate, and 2 (1.3%) could not be scheduled.

Measures

Child report of current symptoms of depression (i.e., past month) was measured using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL),28 a semistructured diagnostic interview. In the K-SADS-PL, symptoms of depression are rigorously assessed in terms of being present most of the time, and the interviewer is trained to probe for information necessary to determine whether a behavior meets symptom criteria. We assessed all nine symptoms of depression, regardless of whether disturbance in mood (i.e., sadness or irritability) or anhedonia was endorsed. In addition to using total number of symptoms endorsed (possible range 0–9), minor and major depressive disorders were generated from the K-SADS according to DSM-IV criteria.29 Minor depression was proposed as a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV and is awaiting further data on validity before a decision on inclusion for DSM-V can be made. This subsyndromal form of major depression is defined using the same duration criteria (2 weeks) and the requirement of disturbance in mood (depressed mood or irritability) or anhedonia, in addition to which, one additional symptom is required. Minor depression differs from dysthymia, which requires a mood disturbance of 1 year in duration, during which time two additional symptoms must be present.

A second interviewer listened to and coded responses from the digital video of the K-SADS-PL interview to assess interrater agreement. Twenty-five percent of the girls’ interviews (n = 39) were randomly selected for this purpose. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for total number of symptoms were 0.92, 0.96, and 0.97 for Years 01, 02, and 03, respectively. Kappa coefficients for minor/major depressive disorders were 0.77, 1.00, and 0.79 for Years 01, 02, and 03, respectively.

Caregivers and interviewers of the girls rated current impairment using the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS),30 a measure of impairment developed for children aged 4 to 18 years. Scores on the CGAS range from 1 to 100, with each decile containing a description of the severity of symptoms in terms of the impact the symptoms have on school, family, and peer relations. Interrater agreement on 42 cases of interviewer-generated CGAS ratings after the child K-SADS was very high: ICC = 0.91. A score of 60 or lower also was used to indicate clinically significant impairment.31

Pubertal development was measured using maternal report on the Peterson Physical Development Scale (PDS).32 The PDS includes four questions about growth spurt, body hair, breast development, and changes in skin scored on four-point scales and one yes/no question about onset of menstruation. In the present study, we used maternal report on the PDS at ages 9 and 10 years to assess the effect of pubertal status on depression at ages 9, 10, and 11 years. Maternal report of pubertal development in comparison with child self-report has been shown to be more closely associated with results from a physical examination.33 Based on maternal report on the PDS, girls were classified into two groups: prepubertal or beginning pubertal (n = 113) and midpubertal or advanced pubertal (n = 111; only one girl was classified as being at an advanced stage of pubertal development) based on categories developed by Crockett.34

Mothers reported on their daughters’ racial backgrounds. Most of the girls (69.8%) were African American or African American and other racial backgrounds (e.g., European, American Indian). The mothers of the remaining girls identified their daughters as European American (30.2%) or Asian American (0.9%). In the analyses using race as a potential moderator of stability, the two Asian American girls were not included.

Poverty was defined as families who reported receiving any welfare assistance such as food stamps, Medicaid, or temporary aid to needy families from the Department of Public Welfare (n = 101).

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were performed in four steps. First, the stability of girls’ depressive symptom counts was tested by computing ICCs across ages 9, 10, and 11 years and by testing the stability of symptom level using Kendall τ-b for nonparametric data. Second, the potential moderating effect of race (African American versus European American), poverty (receipt of public assistance versus no public assistance), and pubertal stage (prepubertal/beginning versus midpubertal/advanced pubertal development) was tested by estimating a path model for each group separately using Mplus 4.2.35 A square-root transformation of the symptom counts was used in the model to better approximate a normal distribution. The transformation reduces the impact of extreme values and therefore provides a more valid estimation. The moderating effect of one covariate was tested, controlling for the other two covariates. Model fit was evaluated using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI), using the recommended cutoffs of 0.08 or lower for SRMR, 0.06 or lower for RMSEA, and 0.95 or higher for CFI.36 The change in χ2 fit statistic was used to determine the presence of a moderating effect. The sample size in the present study is more than sufficient to provide stable results, given the relations modeled in each analysis and the minimal amount of missing data.35

Third, data on the validity of minor and major depression in the present sample are presented by testing the stability of these disorders and level of impairment among diagnostic groups. Fourth, the predictive validity of symptoms at age 9 years to later depressive disorders and impairment at ages 10 and 11 years was tested in a logistic regression model. The effects of pubertal development, race, and poverty on the prediction of depressive disorders were also tested.

RESULTS

Stability of Depression Symptoms

Symptoms of depression at age 9 years were endorsed at the following rate: disturbance in concentration, 33.6%; appetite disturbance, 32.3%; sleep disturbance, 26.3%; feelings of worthlessness or guilt, 18.5%; motor disturbance, 15.5%; suicidal ideation or behavior, 10.3%; fatigue, 10.3%; mood disturbance, 9.5%; and anhedonia, 6.9%.

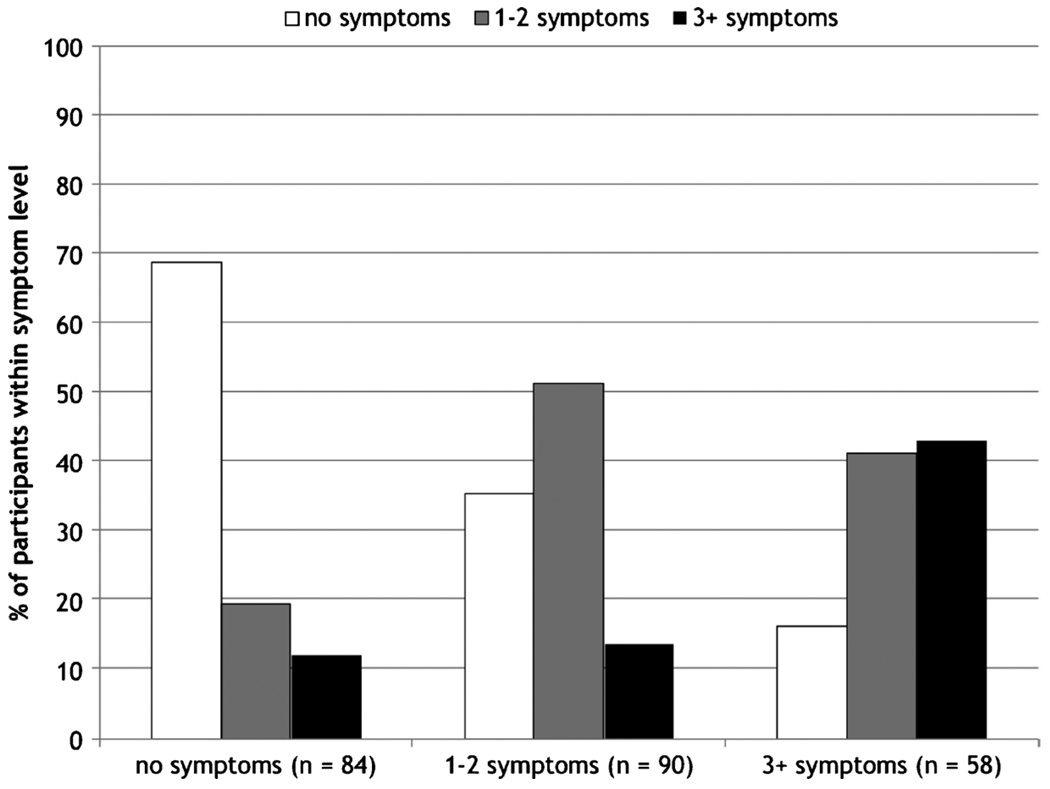

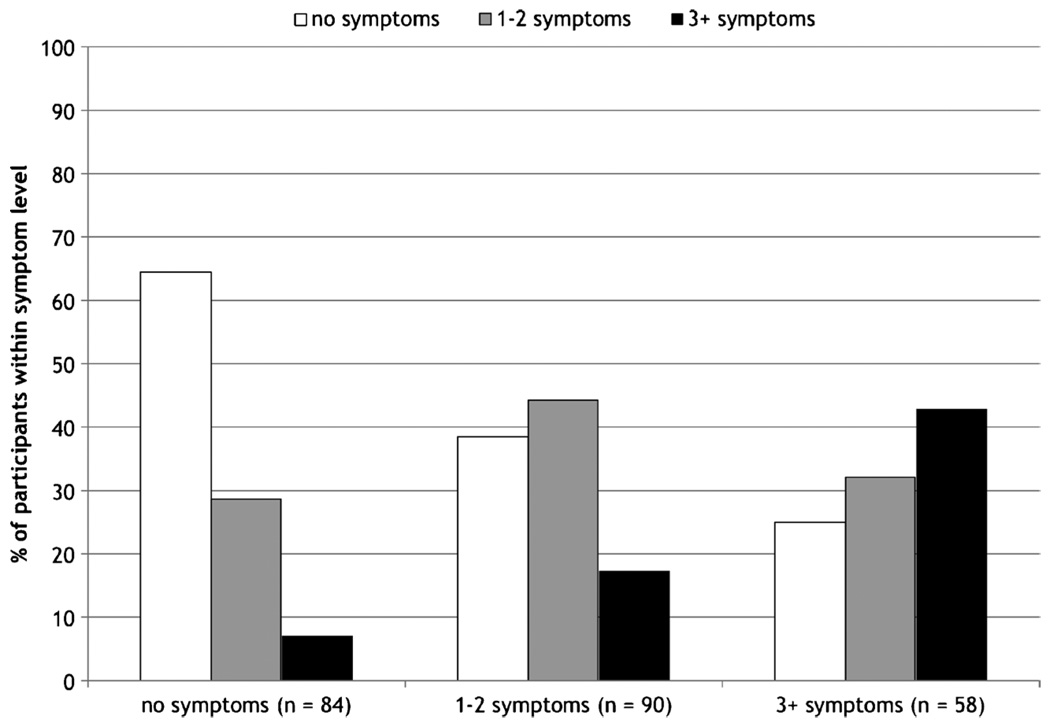

Intraclass correlation coefficients were computed to test the stability of depression symptoms across the 3 years. Symptoms were moderately stable from ages 9 to 10 years (ICC = 0.45, p < .001), 10 to 11 years (ICC = 0.40, p < .001), and 9 to 11 years (ICC = 0.59, p < .001). To examine whether this moderate level of stability was accounted for primarily by stability of nonsymptomatic cases, symptom level (none, one to two, and three or more symptoms) at age 9 years was cross-tabulated with symptom level at ages 10 and 11 years. This allowed us to examine stability among relatively equal groups at symptom levels that could be interpreted as none, mild, and moderate levels of depressive symptoms. At age 9 years, 84 girls (36.2%) reported no symptoms, 90 (38.8%) reported 1 to 2 symptoms, and 58 (25.0%) reported 3 or more symptoms. As shown in Figure 1, more than 80% of girls who reported 3 or more symptoms at age 9 years continued to report symptoms at age 10 years (Kendall τ−b = 0.39, p < .0001). Similar results were observed for the stability of symptom level from ages 9 to 11 years (Kendall τ−b = 0.34, p < .0001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Stability of DSM-IV symptoms of depression in girls from ages 9 to 10 years.

Fig. 2.

Stability of DSM-IV symptoms of depression in girls from ages 9 to 11 years.

Moderation of the Stability of Depressive Symptoms

A stability model was first estimated with no equality constraints on parameters between the different racial, poverty, and pubertal groups. Allowing for the correlation of the residuals of ages 9 and 11 years, depression variables yielded a good fit: χ28 = 6.42, p > .05; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.00–0.10); SRMR = 0.04. To test the effect of the hypothesized moderators, the model was estimated again with the stability coefficients set to be equal between groups. The change in the model χ2 was used to determine whether stability was affected by race, poverty, or pubertal stage, and if so, the stability coefficients were examined to determine the nature of the moderating effect.

Race did not moderate the stability of depressive symptoms, as evidenced by similar stability coefficients for African American and European American girls from ages 9 to 10 years (β= .42 and 0.54, p values < .001) and from ages 10 to 11 years (β = .44 and .42, p values < .001). Receipt of public assistance was a significant moderator. Stability of depressive symptoms from ages 10 and 11 years was greater for girls whose families received public assistance (β = .59, p < .001) than girls whose families did not (β = .22, p < .01). The stability coefficients between ages 9 and 10 years did not differ between poverty and nonpoverty groups (β = .35 and .22, p < .001). In testing the moderating effect of pubertal stage, stability did not differ between prepuberty to beginning and middle to advanced puberty groups from ages 9 to 10 years (β = .44 and .44, p values < .001) or from ages 10 to 11 years (β = .37 and .48, p values < .001).

Validity of Minor and Major Depression in Preadolescent Girls

Before testing the predictive validity of DSM-IV symptoms of depression to later disorders, data on the validity of the disorders in the present sample are presented. At age 9 years, the rate of minor depression (6.0%) is equal to that of major depression. At age 10 years, the rate of major depression (2.2%) is about a third of the rate of minor depression (6.0%). By age 11 years, the rates are again similar but lower than that observed in the first year (3.0% for major depression and 4.3% for minor depression). These rates are higher than those reported in population-based samples of children,1 reflecting the success of the screening to increase the base rate of depressive disorders.

Among the 28 girls meeting the criteria for minor and major depression at age 9 years, symptoms of depression were endorsed at the following rate: disturbance in concentration, 75.0%; mood disturbance, 71.4%; feelings of worthlessness or guilt, 64.3%; appetite disturbance, 64.3%; anhedonia, 53.6%; sleep disturbance, 42.9%; motor disturbance, 50.0%; suicidal ideation or behavior, 42.9%; and fatigue, 17.9%. Note that mood disturbance or anhedonia is required for the diagnosis of minor or major depression.

Stability of minor and major depression during this period was high. The odds of meeting the criteria for minor or major depression at age 10 or 11 years, given the presence of minor or major depression at age 9 years, were 3.0 (95% CI 1.12–8.07, p < .05). Race, poverty, and pubertal development at age 9 years were not associated with later depressive disorders, nor did these covariates interact with depressive disorders at age 9 years to increase the stability of depressive disorders.

Caregivers’ and interviewers’ concurrent and prospective impairment ratings were significantly different across the three diagnostic groups at age 9 years (no depressive disorder, minor depression, and major depression) as tested by analysis of variance (Table 1). Post hoc comparisons revealed that, in three of the four analysis of variance models, the average impairment ratings among girls diagnosed with minor depression was significantly lower, reflecting greater impairment, than girls with no depressive disorders and not different from girls diagnosed with major depression.

TABLE 1.

Concurrent and Prospective Impairment Among Diagnostic Groups at Age 9 Years

| Diagnostic Groups at Age 9 Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Minor | Major | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | df | F | p | |

| Age 9 y (CGAS) | ||||||

| Caregiver | 82.7 (10.4)a | 74.6 (14.7)b | 76.9 (13.2)a,b | 2,229 | 5.13 | .007 |

| Interviewer | 67.1 (11.0)a | 56.4 (6.1)b | 50.4 (7.5)b | 2,229 | 21.75 | .000 |

| Age 10 y (CGAS) | ||||||

| Caregiver | 85.4 (9.2)a | 77.6 (14.7)b | 77.7 (16.7)b | 2,224 | 6.87 | .001 |

| Interviewer | 67.9 (10.1)a | 63.6 (3.1)a | 57.8 (8.6)b | 2,224 | 7.05 | .001 |

Note: CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale.

Different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences tested by Tukey post hoc tests.

Predictive Validity of Symptoms to Depressive Disorders and Impairment at Ages 10 and 11 Years

To test the predictive validity of DSM-IV symptoms of depression, the girls who already met the criteria for minor or major depression at age 9 years were excluded (n = 28). Symptoms of depression assessed at age 9 years among the remaining girls were predictive of meeting the criteria for minor or major depression at age 10 or 11 years. For each increase in number of depression symptoms at age 9 years, there was nearly a twofold increase in the risk of a later depressive disorder (odds ratio 1.9 [95% CI 1.01–3.51], p < .05). In fact, of the 23 girls who met the criteria for minor or major depression at age 10 or 11 years, 18 (78.3%) had at least 1 symptom at age 9 years. Race, poverty, and pubertal development at age 9 years were not associated with later depressive disorders. Similar results were found in predicting interviewer-rated impairment. For each increase in symptom count at age 9 years, there was nearly a twofold increase in the risk of having a CGAS rating below 60 at age 10 or 11 years (odds ratio 1.7 [95% CI 1.33–2.13], p < .001).

DISCUSSION

Depressive disorders are among the most impairing medical or mental condition for females.7 For females in particular, onset of depression is highly likely to lead to recurrence and chronicity.5,6 Primary and secondary prevention of depression, therefore, needs to be a public health priority. Critical to the successful prevention of depression is defining the developmental phenomenology of the disorder. Our goal in the present study was to contribute to that effort by testing the stability and predictive validity of DSM-IV symptoms of depression in a nonreferred sample during the preadolescent period.

The results showed that symptoms of depression are fairly stable during the preadolescent period among girls. Most girls in the present sample reported one or more symptoms of depression, and most of these girls continued to report depressive symptoms at ages 10 and 11 years. Thus, stability was not accounted for only by stable low cases. The stability coefficients for DSM-IV symptom counts generated in the present study for a 1- to 2-year interval were in the moderate range (i.e., 0.40–0.59 for continuous symptoms counts and 0.34–0.39 for symptom level stability). These results suggest that, although there is room for movement during preadolescence both in terms of decreases in depression symptoms over time and emergence of symptoms in girls who previously did not endorse symptoms, a substantial number of girls who evidence symptoms during preadolescence will continue to do so for the next few years.

The results also demonstrate that symptoms of depression that emerge during this period are not benign. They are predictive of depressive disorders and impairment in the following 2 years. There was a nearly twofold increase in the risk of subsequent depressive disorder and interviewer-rated impairment at ages 10 to 11 years for every increase in number of depression symptoms at age 9 years. This is evidence of significant morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in preadolescent girls.

Although still under consideration for DSM-V, minor depression seems to be equivalent to major depression in terms of prognosis regarding impairment, use of mental health services, future major depressive episodes, and suicidality.14,15 Some investigators have argued and provided evidence for the contention that minor and major depression fall along a continuum of a single clinical disorder.37 Therefore, evidence of predictive validity to both minor and major depression is highly relevant clinically. Moreover, further evidence of the validity of minor depression was provided in the present study; the level of impairment among the girls who met the criteria for minor depression was significantly different from the girls without a depressive diagnosis and did not differ from the girls with a diagnosis of major depression. That being said, a test of the predictive validity of minor depression in childhood to depression in adolescence needs to be executed to fully validate this diagnosis.

In the present study, the predictive validity of depression symptoms and disorders at age 9 years falls between the lack of validity reported in the Dunedin Study and the high validity reported in the Great Smoky Mountains Study, and this makes sense, given the difference in methods and sampling. A structured method of assessment, which was not used in the Dunedin Study, may be a requirement for reliably assessing depressive symptoms in children. Reliability of symptoms obviously could influence the predictive validity of those symptoms leading to an underestimate in the Dunedin Study. In the Great Smoky Mountains Study, a structured method of assessment was used to assess the predictive validity of depressive disorders at time 1, at ages 9 to 13 years, to depressive disorders through age 16 years using between 3 and 5 years of assessments. The prevalence of depressive disorders at ages 9 to 10 years, however, was less than 1%. Thus, the 20-fold increase in depressive disorders at age 16 years was probably most heavily influenced by disorders appearing after age 9 years. The present study adds to this existing literature by documenting that, as early as age of 9 years, symptoms of depression demonstrate predictive validity.

Only current (past month) depressive symptoms were assessed in the present study, an approach that has its advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that problems associated with retrospective recall are avoided. Recall for past episodes of depression is poor among young adults, as is recall for key symptoms of depression such as depressed mood.38 An age younger than 12 years increases the odds of inaccurate recall of depressed mood and anhedonia 2 years later by a factor of 9.6.39 Thus, by focusing only on present depression, we likely reduced the error often introduced into estimates of stability from lack of reliability. The disadvantage is that the narrow window of assessment may have led to incorrectly classifying some girls as not depressed who had in fact experienced depression during the past year. Therefore, this is a fairly conservative test of the hypothesis that childhood depressive symptoms and disorders demonstrate predictive validity.

Poverty, but not race, was associated with stability of depressive symptoms from ages 10 to 11 years. If this pattern of association with depressive symptoms continued over time, it could lead to a higher incidence of depression among females living in poverty as they continue to experience recurrence, whereas those not living in poverty may be more likely to remit. It is interesting to note that the role of environmental factors, such as poverty, in the etiology versus the stability of symptoms and disorders may vary, depending on the type of disorder. For example, there is evidence that poverty is associated with the presence of disruptive behavior disorders in childhood40 but not the stability of disruptive behavior over time.41 Because socioeconomic factors such as poverty have biological consequences,42 it is plausible that they may differentially have an impact on disorders at different points in the developmental trajectory.

Pubertal stage of development at age 9 years was not associated with the stability of depressive symptoms from ages 9 to 11 years or the predictive validity of depressive symptoms to later disorders and impairment. Given the developmental stage of the participants, this was essentially a test of the effect of being at an earlier stage of pubertal development versus midpuberty on depression. Because approximately 50% of the girls fell into each category, it is difficult to argue that this comparison yielded any information about early pubertal development within this sample. Notwithstanding these limitations, this is one of the first studies to test associations between pubertal development and depressive symptoms in this early developmental period, which has been a significant gap in the puberty–depression literature.43

There are at least two important areas of expansion for this program of research. One is the predictive validity of specific symptoms of depression. There is evidence from studies of adults that anhedonia is predictive of depressive disorders.44 In a study of adolescent-onset depression, depressed mood explained unique variance in the prediction of later depression.45 This research is complicated by the fact that mood disturbance or anhedonia is required to meet criteria for depression. Overcoming these statistical complexities will be necessary for testing the hypothesis that specific combinations of symptoms, as opposed to symptom level, demonstrate the highest predictive validity.

The second area is the relative predictive validity of informants. In the present study, the focus was on child-reported depressive symptoms, and there are data to support the validity of preadolescent girls’ reports of depressive symptoms.46,47 There are also data pointing to a relatively low level of agreement between parents and children.47,48 For example, in the Pittsburgh Girls Study, only 2% of the variance in caregiver-reported depression symptoms was accounted for by child report of depression symptoms.47 This raises the question of whether one informant demonstrates greater validity than the other or whether using a best estimate approach, in which the endorsement by either informant is the optimal approach. Before combining informants, however, the equivalence of the diagnostic constructs assessed by each informant would need to be established.

In summary, early-emerging symptoms of depression in girls are stable and predictive of meeting the criteria for major and minor depressive disorders and impairment. Without data on the incidence of depression during adolescence in this sample, we cannot yet state that the best predictor of adolescent-onset depression is childhood symptoms. Based on the results from the present study, however, it seems highly plausible that that will indeed be the case. If so, then efforts to prevent depression among females do not need to be limited to the period of adolescence but should focus on preadolescence too. The high likelihood of recurrence of depression requires aggressive treatment of initial episodes. Treatment of symptoms and subsyndromal forms of depression in preadolescence may be one avenue toward reducing the morbidity associated with this disorder.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01 MH66167 (to Dr. Keenan).

The authors thank Dr. Benjamin Lahey for comments on an earlier draft and the families participating in the Learning About Girls’ Emotions Study.

This article is the subject of an editorial by Dr. Bonnie T. Zima in this issue.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Kate Keenan, Department of Psychiatry at the University of Chicago

Alison Hipwell, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

Xin Feng, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

Dara Babinski, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

Amanda Hinze, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

Michal Rischall, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

Angela Henneberger, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh at the time the work was completed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, et al. Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years, Part I. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1996;35:1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva P, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichstrom L. The emergence of gender difference in depressed mood during adolescence: the role of intensified gender socialization. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:232–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Dis. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCauley E, Myers K, Mitchell J, Calderon R, Schloredt K, Treder R. Depression in young people: Initial presentation and clinical course. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1993;32:714–722. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovacs M. Depressive disorders in childhood: an impressionistic landscape. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:287–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. pp. 117–200. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacs M, Obrosky DS, Sherrill J. Developmental changes in the phenomenology of depression in girls compared to boys from childhood onward. J Affect Dis. 2003;74:33–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tram JM, Cole DA. A multimethod examination of the stability of depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:674–686. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Fombonne E, Poulton R, Martin J. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:215–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder and depression: childhood risk factors in a birth cohort followed to age 32. Psychol Med. 2007;37:441–452. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelbrock C, Costello AJ, Dulcan MK, Kalas R, Conover NC. Age differences in the reliability of the psychiatric interview of the child. Child Dev. 1985;56:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramirez R, et al. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:888–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fergusson DM, Horwood L, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remick RA, Sadovnick AD, Lam RW, Zis AP, Yee IM. Major depression, minor depression, and double depression: are they distinct clinical entities? Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:347–353. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960726)67:4<347::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angold A, Rutter M. Effects of age and pubertal status on depression in a large clinical sample. Dev Psychopathol. 1992;4:5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laitinen-Krispijn S, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The role of pubertal progress in the development of depression in early adolescence. J Affect Dis. 1999;54:211–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: pubertal influences on girls' vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Dev. 1996;67:3386–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stice E, Presnell K, Bearman SK. Relation of early menarche to depression, eating disorders, substance abuse, and comorbid psychopathology among adolescent girls. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:608–619. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Socio-economic status, family disruption and residential stability in childhood: relation to onset, recurrence and remission of major depression. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1341–1355. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leech SL, Larkby CA, Day R, Day NL. Predictors and correlates of high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among children at age 10. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2006;45:223–230. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000184930.18552.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: race and gender differences. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2004;7:133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, Kroneman L. Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and delinquent behaviour. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2002;2:99–118. doi: 10.1002/cbm.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventory. Stony Brook: State University of New York at Stony Brook; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setterberg S, Bird H, Gould M, Shaffer D, Fisher P. Parent and Interviewer Versions of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. New York: Columbia University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bird HR. The assessment of functional impairment. In: Shaffer D, Lucas C, Richters JE, editors. Diagnostic Assessment in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorn LD, Dahl RE, Woodward HR, Biro F. Defining the boundaries of early adolescence: a user's guide to assessing pubertal status and pubertal timing in research with adolescents. Appl Dev Sci. 2006;10:30–56. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crockett L. Pubertal Development Scale: Pubertal Categories. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, Department of Human Development and Family Studies; [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:694–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells JE, Horwood LJ. How accurate is recall of key symptoms of depression? A comparison of recall and longitudinal reports. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1001–1011. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fendrich M, Warner V. Symptom and substance use reporting consistency over two years for offspring at high and low risk for depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1994;22:425–439. doi: 10.1007/BF02168083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinhausen H-C, Erdin A. Abnormal psychosocial situations and ICD-10 diagnoses in children and adolescents attending a psychiatric service. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;33:731–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahey BB, Loeber R, Hart EL, et al. Four-year longitudinal study of conduct disorder in boys: patterns and predictors of persistence. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:83–93. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristenson M, Eriksen H, Sluiter J, Starke D, Ursin H. Psychobiological mechanisms of socioeconomic differences in health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;8:1511–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angold A, Costello EJ. Puberty and depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15:919–937. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, Strawbridge WJ. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: a prospective perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:81–88. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Georgiades K, Lewinsohn PM, Monroe SM, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in adolescence: the role of subthreshold symptoms. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2006;45:936–944. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000223313.25536.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ialongo NS, Edelsohn G, Kellam SG. A further look at the prognostic power of young children’s report of depressed mood and feelings. Child Dev. 2001;72:736–747. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keenan K, Hipwell A, Duax J, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R. Phenomenology of depression in young girls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1098–1106. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000131137.09111.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin C. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: predictors of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]