Abstract

Multiple functionally independent pools of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] have been postulated to occur in the cell membrane, but the existing techniques lack sufficient resolution to unequivocally confirm their presence. To analyze the distribution of PI(4,5)P2 at the nanoscale, we developed an electron microscopic technique that probes the freeze-fractured membrane preparation by the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-δ1. This method does not require chemical fixation or expression of artificial probes, it is applicable to any cell in vivo and in vitro, and it can define the PI(4,5)P2 distribution quantitatively. By using this method, we found that PI(4,5)P2 is highly concentrated at the rim of caveolae both in cultured fibroblasts and mouse smooth muscle cells in vivo. PI(4,5)P2 was also enriched in the coated pit, but only a low level of clustering was observed in the flat undifferentiated membrane. When cells were treated with angiotensin II, the PI(4,5)P2 level in the undifferentiated membrane decreased to 37.9% within 10 sec and then returned to the initial level. Notably, the PI(4,5)P2 level in caveolae showed a slower but more drastic change and decreased to 20.6% at 40 sec, whereas the PI(4,5)P2 level in the coated pit was relatively constant and decreased only to 70.2% at 10 sec. These results show the presence of distinct PI(4,5)P2 pools in the cell membrane and suggest a unique role for caveolae in phosphoinositide signaling.

Keywords: cell membrane, electron microscopy, phosphoinositide, microdomain, angiotensin II

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] plays critical roles in multiple cellular phenomena, such as ion channel regulation, endocytosis, exocytosis, and cytoskeletal assembly. Besides working as an effector that regulates various proteins, PI(4,5)P2 is also important as the precursor of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3], phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, and diacylglycerol (for a recent review, see ref. 1). The detailed mechanism for how a single lipid molecule can possess so many different functions has not been elucidated, but it is widely speculated that spatially restricted pools of PI(4,5)P2 may exist in the cell membrane (2, 3).

Various molecular mechanisms that may enable the local concentration of PI(4,5)P2 have been hypothesized (3–5). In fact, the GFP-tagged pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of phospholipase C-δ1 (PLC-δ1) that binds to PI(4,5)P2 in live cells (6, 7) often showed uneven distributions in the membrane (8–11). However, whether this observation really indicates a local PI(4,5)P2 accumulation has been controversial (5), and at least some of the results can be explained by subresolution membrane folding (12). Thus, PI(4,5)P2 pools that are correlated with their functional heterogeneity have not been demonstrated unequivocally.

The failure to find a local concentration of PI(4,5)P2 does not necessarily refute its occurrence, but may instead be the result of technical insufficiency. Imaging techniques at the light microscopic level may not have sufficient spatial resolution to detect local concentrations in small scales. In addition, other limitations of the GFP-PH method have been pointed out (13, 14): the GFP-PH probe that is expressed in live cells may disturb intracellular signaling by sequestering PI(4,5)P2, GFP-PH is not likely to detect PI(4,5)P2 that is bound to endogenous proteins, and Ins(1,4,5)P3 may compete with PI(4,5)P2 for binding to GFP-PH. On the other hand, methods using electron microscopy can detect local heterogeneities at a small scale (15, 16), but the use of aldehyde-fixed cryosections is a potential problem because lipids, including PI(4,5)P2, cannot be securely immobilized by chemical fixation and may be redistributed during the labeling procedure (17).

In the present study, we developed an electron microscopic method that uses freeze-fracture replicas as a substrate for the PI(4,5)P2 labeling. Live cells were rapidly frozen without chemical fixation, and the membrane halves split at the hydrophobic interface were cast by vacuum evaporation of carbon and platinum. Membrane lipids were thus physically stabilized, and the exposed hydrophilic surface could be probed without artificial perturbations (18, 19). By this method, we found that PI(4,5)P2 was highly concentrated in caveolae and the clathrin-coated pit, and upon agonist stimulation, PI(4,5)P2 in those indentations showed behaviors distinct from that in the flat undifferentiated membrane area. This result unequivocally demonstrated the spatial-temporal heterogeneity of PI(4,5)P2 in the cell membrane. It also revealed that caveolae, a membrane microdomain implicated in diverse functions (20), also play a unique role in the PI(4,5)P2-related phenomena.

Results

Development of an Electron Microscopic Technique.

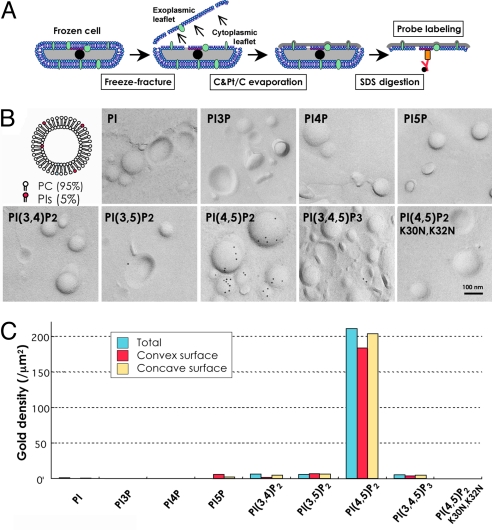

Live cells were rapidly frozen, freeze-fractured, and cast by a thin layer of carbon and platinum by vacuum evaporation (Fig. 1A) (21). Recombinant GST-tagged PH domain of mouse PLC-δ1 (GST-PH) was used to label PI(4,5)P2 in the freeze-fracture replica. To verify the binding specificity of GST-PH to PI(4,5)P2, liposomes were prepared by mixing 95 mol % of phosphatidylcholine and 5 mol % of either phosphatidylinositol or 1 of the 7 phosphoinositides. Then, their freeze-fracture replicas were incubated with GST-PH, followed by rabbit anti-GST antibody and colloidal gold conjugated with protein A or anti-rabbit IgG antibody. The labeling was virtually restricted to the PI(4,5)P2-containing liposome replica, and the labeling density per unit area was more than 50 times higher than that of the other 7 liposome replicas (Fig. 1 B and C). The labeling densities in the convex and concave fracture faces of the liposome membrane were comparable (Fig. 1C). The specificity of labeling was further confirmed by a PH domain mutant that lacks binding capacity for PI(4,5)P2. This mutant with 2 amino acid substitutions, GST-PH(K30N, K32N) (7), produced little labeling in the PI(4,5)P2 liposome (Fig. 1 B and C). These results showed that GST-PH is a specific probe for PI(4,5)P2 in freeze-fracture replicas.

Fig. 1.

Labeling of the liposome. (A) Outline of the method. Cells were rapidly frozen, freeze-fractured, and evaporated with carbon (C) and platinum/carbon (Pt/C) in vacuum. The replica of the split membrane was digested with SDS to remove noncast molecules and labeled by GST-PH. Both the cytoplasmic and exoplasmic halves of the membrane were examined. (B) Labeling of small unilamellar liposome replicas. Freeze-fracture replicas of liposomes containing 95 mol % of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and 5 mol % of phosphatidylinositol or a phosphoinositide were labeled. Only liposomes containing PI(4,5)P2 were labeled intensely by GST-PH. A PH mutant, GST-PH(K30N, K32N), which does not bind PI(4,5)P2, showed little labeling in the PI(4,5)P2-containing liposome. (C) Quantification of the GST-PH labeling in the liposomes. The number of gold particles per 1 μm2 of the liposome surface is shown (blue). The labeling on the convex (red) and concave (yellow) surfaces showed equivalent results.

We found previously that replicas prepared by depositing carbon (C) before platinum/carbon (Pt/C) gave much better labeling for gangliosides than the traditional sequence that deposits Pt/C first (21). For PI(4,5)P2 as well, the replica prepared in the order of C-Pt/C-C (3 layers) or C-Pt/C (2 layers) showed much better labeling than the conventional Pt/C-C replica. The C-Pt/C-C replica was used for the following experiments because by keeping the first C layer thin, it can delineate ultrastructures better than the C-Pt/C replica.

When GST-PH was used at a concentration of 100 ng/mL, the labeling in replicas of giant unilamellar liposomes containing 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mol % PI(4,5)P2 occurred roughly in proportion to the molar ratio of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. S1). When a higher concentration of GST-PH was applied, the labeling density increased, but the linear relationship between the labeling density and the molar PI(4,5)P2 content was lost, probably because of the steric hindrance between the probes. Because the above range of PI(4,5)P2 molar ratio should cover its actual content in the cell membrane, it is reasonable to assume that for the most part, the labeling by 100 ng/mL GST-PH reflects the real PI(4,5)P2 distribution in the specimen. The effect of the GST-PH concentration on the labeling pattern was examined further in a fibroblast sample, as described below.

PI(4,5)P2 in Cultured Human Fibroblasts and Mouse Smooth Muscle Cells in Vivo.

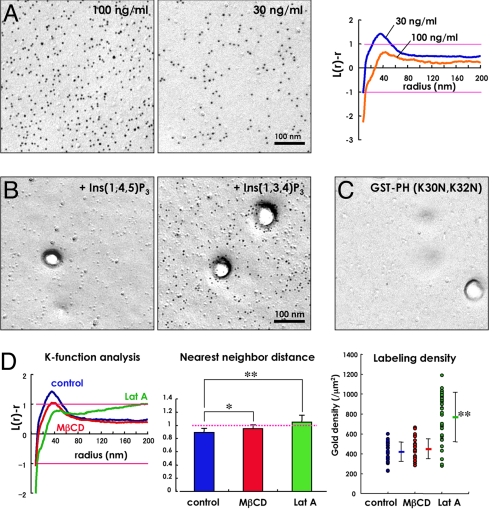

In the freeze-fracture replica of normal human fibroblasts in culture, GST-PH used at 30–100 ng/mL labeled only the P face or cytoplasmic leaflet of the cell membrane, and not the E face or exoplasmic leaflet (Fig. 2A). Two control experiments verified the specificity of this labeling. First, preincubation of GST-PH with Ins(1,4,5)P3 but not Ins(1,3,4)P3 eliminated the labeling (Fig. 2B). Second, little labeling was observed with GST-PH(K30N, K32N) used at the same concentration as GST-PH (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, treatment with PLC-δ3 or a phosphoinositide phosphatase (SKIP) did not abolish the labeling. However, this may have been because the enzymes are unable to work on the PI(4,5)P2 that is embedded in the replica (22, 23).

Fig. 2.

Labeling in the flat undifferentiated area of the cell membrane. (A) Distribution of PI(4,5)P2 in the P face of the flat undifferentiated cell membrane of the human fibroblast in culture. GST-PH was used at a concentration of 100 ng/mL (Left) or 30 ng/mL (Right). The mean L(r) − r curve compiled from 30 randomly chosen areas showed that the labeling by 100 ng/mL GST-PH was randomly distributed, whereas that by 30 ng/mL GST-PH showed weak clustering. (B) Effects of inositol trisphosphates on the PI(4,5)P2 labeling. GST-PH (100 ng/mL) was preincubated with either 1 mM Ins(1,4,5)P3 or 1 mM Ins(1,3,4)P3 before applying to replicas. Ins(1,4,5)P3 abolished the labeling completely, whereas Ins(1,3,4)P3 did not. (C) Labeling by GST-PH (K30N, K32N) used at 100 ng/mL. Virtually no labeling was observed. (D) The clustering that was detected by 30 ng/mL GST-PH decreased when cells were treated with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) for 60 min to extract free cholesterol or with 1 μM latrunculin A (Lat A) for 10 min to depolymerize actin. After these treatments, the normalized nearest neighbor distance became closer to one, and the average labeling density increased (*, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001).

The labeling of PI(4,5)P2 in the flat undifferentiated membrane was distributed randomly when GST-PH was used at 100 ng/mL, whereas the label showed weak clustering when GST-PH was used at 30 ng/mL (Fig. 2A). In the latter case, the L(r) − r curve showed that the average radius of the label cluster was 36 nm; considering the arm length of the probes (21), the average size of the PI(4,5)P2 cluster was estimated to be in the range of 40–72 nm in diameter. The different results by the 2 GST-PH concentrations suggested that a low level of steric hindrance among the probes occurred locally when 100 ng/mL GST-PH was used. This assumption is supported by the fact that the point distribution pattern of the label is changed from clustering to mutual segregation by increasing the GST-PH concentration from 10 to 10,000 ng/mL (Fig. S2).

The average densities of the PI(4,5)P2 label in the replica were 422.3 gold particles per square micrometer (GST-PH, 30 ng/mL) and 1,734.3 gold particles per square micrometer (GST-PH, 100 ng/mL). Previously, we determined that the 3-step labeling procedure (GST-PH, anti-GST, and protein A-gold) amplifies the signal intensity 1.08 times (21). Thus, the above labeling is thought to capture 391.0 and 1,605.8 PI(4,5)P2 molecules per square micrometer, respectively. Based on the estimation that the average density of PI(4,5)P2 in the cell membrane is ≈3,000–5,000 molecules per square micrometer (2, 24), the capture ratio of this method may be in the range of 7.8–13.0% (GST-PH, 30 ng/mL) or 32.1–53.5% (GST-PH, 100 ng/mL). To observe the distribution pattern properly on one hand and to obtain a high capture ratio on the other, most specimens in the following experiments were labeled by the 2 different concentrations of GST-PH.

The clustering of the label observed by 30 ng/mL GST-PH was reduced when the cell was treated with either 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin for 60 min to extract free cholesterol or 1 μM latrunculin A for 10 min to depolymerize actin (Fig. 2D). These treatments made the normalized nearest neighbor distance closer to one and increased the average labeling density (Fig. 2D). These results can also be explained by a decrease of the PI(4,5)P2 clustering. The clustering of PI(4,5)P2 was observed even in caveolin-1-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts.

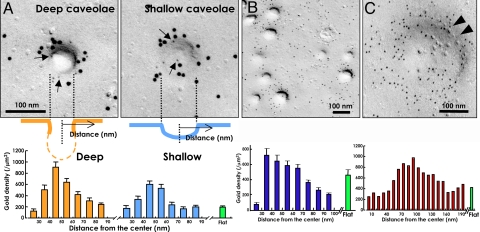

Regardless of the GST-PH concentration, the PI(4,5)P2 labeling occurred intensely around caveolae. Caveolae were observed as indentations of variable depths and ≈60–80 nm in diameter, and they were identified by immunolabeling of caveolin-1 (Fig. 3A) (25). The labeling for PI(4,5)P2 was the most intense at the rim of caveolae, or at about 30–50 nm from the caveolar center. The labeling density in the zone farther than 70–90 nm from the center was equivalent to that in the flat undifferentiated membrane (Fig. 3A). The intense labeling was observed regardless of the caveolar depth, indicating that it was not simply caused by superimposition of gold particles along the lateral wall of the deeply invaginated caveolae. It must also be noted that the bottoms of deep caveolae were not retained in the replica, primarily because the fracture plane passed through the neck of the indentation (see schemes of Fig. 3A). The caveolar concentration of PI(4,5)P2 persisted even in cells treated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin or latrunculin A, although morphologically discernible caveolae decreased after the former treatment.

Fig. 3.

Labeling in caveolae and coated pits. GST-PH was applied at a concentration of 30 ng/mL. (A) Intense labeling of PI(4,5)P2 at the caveolar rim. The large (10-nm) and small (5-nm; arrows) gold particles label PI(4,5)P2 and caveolin-1, respectively. Deep caveolae were fractured at the neck portion and appeared electron-lucent in the center because Pt/C evaporation did not reach the deep portion. In contrast, shallow caveolae were observed all along the contour. To measure the labeling density in relation to the distance from the caveolar center, 30 caveolae were randomly chosen from 3 independent experiments. The caveolar labeling was most intense at 30–50 nm from the center, and the labeling density was much higher than that in the flat undifferentiated membrane area (green bar). (B) Dense caveolar labeling of PI(4,5)P2 in the mouse smooth muscle (vas deferens) in vivo. The caveolae also showed intense PI(4,5)P2 labeling at the rim. The labeling density in the flat undifferentiated membrane is shown as a reference (green bar). (C) Labeling of PI(4,5)P2 in the coated pit that was observed as a smooth indentation of 150–200 nm in diameter (arrowheads). The size, morphology, and lack of caveolin-1 labeling suggested that they are clathrin-coated pits. The labeling density of PI(4,5)P2 was the highest at the rim, or 70–100 nm from the center. The labeling density in the flat undifferentiated membrane is shown as a reference (green bar). For this quantification, protein A conjugated to 5-nm colloidal gold was used so that the labeling density in the flat undifferentiated membrane (green bar) is different from A.

One of the advantages of the present technique is that it can be applied to cells in natural tissues as well as to cultured cells without any prior manipulation. We excised pieces of vas deferens from anesthetized mice, froze them rapidly by high-pressure freezing, and processed them by the same procedure as cultured cells. The smooth muscle cell in the vas deferens wall showed arrays of caveolae, which were also densely labeled for PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 3B). A similar concentration of PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae was also observed in the smooth muscle cells of mouse intestine and urinary bladder, as well as in cultured Vero and MDCK cells. The result indicated that the caveolar concentration of PI(4,5)P2 occurs generally regardless of the cell type.

In addition to caveolae, smooth indentations of 150–200 nm in diameter, which were identified as clathrin-coated pits based on their shape, size, and lack of caveolin-1, were also labeled positively for PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 3C). This was consistent with previous results (26, 27). The labeling in the coated pit was also intense at the rim or in the zone of 70–100 nm from the center (Fig. 3C).

A Distinct Behavior of PI(4,5)P2 in Caveolae.

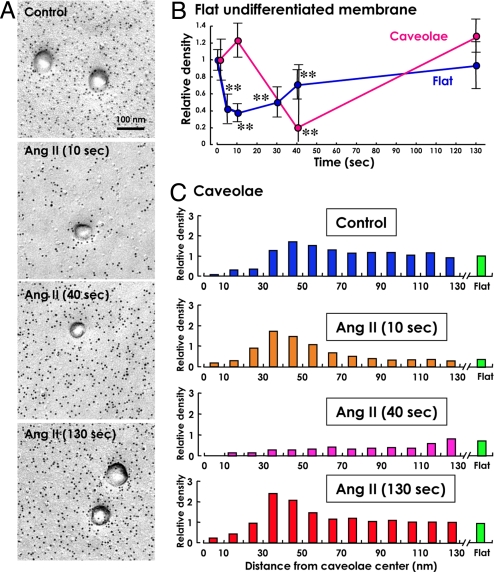

To observe changes of PI(4,5)P2 upon agonist stimulation, human fibroblasts were treated with 1 μM angiotensin II (Ang II) at 25 °C. The responsiveness of the cell to Ang II was verified by a sharp increase in [Ca2+]i immediately after its application (Fig. S3A). This [Ca2+]i rise was completely abrogated when the cell was pretreated with 1 μM losartan for 10 min, indicating that the response was mediated by the AT1 receptor (Fig. S3B). By using the replica labeling technique, a decrease in PI(4,5)P2 in the undifferentiated membrane was detected as early as 5 sec after the Ang II stimulation (Fig. 4B). The labeling density was lowest at 10 sec, began to recover at 40 sec, and finally returned to the initial level at 130 sec (Fig. 4 A and B). This time course was very similar to that observed by live imaging of YFP-PLC-δ1-PH (Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Labeling after Ang II stimulation. GST-PH was applied at a concentration of 100 ng/mL. (A) Representative micrographs of the PI(4,5)P2 labeling before and 10, 40, and 130 sec after the treatment with 1 μM Ang II. (B) The time course of the labeling intensity change. The relative labeling intensity was shown by taking the labeling density of the control sample as the standard (the average ± standard deviation; **, P < 0.001). Thirty areas of the undifferentiated membrane and 30 caveolae were randomly chosen for each time point. For caveolae, the labeling at 30–50 nm from the center was measured. (C) The labeling intensity in relation to the distance from the caveolar center. The labeling density in the undifferentiated membrane of the untreated cell was taken as the standard. Thirty caveolae were randomly chosen for each time point. The labeling at 30–50 nm from the caveolar center did not change significantly at 5 sec and 10 sec after the Ang II stimulation. At 40 sec, the caveolar labeling decreased significantly, whereas the labeling in the flat membrane started to recover and was denser than that of the caveolar rim. The caveolar labeling returned to the control level at 130 sec.

In contrast to the labeling in the flat undifferentiated membrane, the labeling around caveolae did not show a decrease 10 sec after the Ang II stimulation (Fig. 4). The labeling density of PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae showed a significant decrease 40 sec after the agonist application, and at this time point it was comparable to or even lower than in the undifferentiated membrane. The labeling in caveolae increased thereafter and returned to the initial level 130 sec after the stimulation.

The labeling in coated pits decreased 10 sec after the Ang II stimulation, but the decrease was less significant than that in the undifferentiated membrane (Fig. S5). Moreover, the labeling recovered to the initial level 40 sec after the stimulation. Whereas the labeling in the undifferentiated membrane and at the caveolar rim (in the zone 30–50 nm from the center) decreased to as low as 37.9% and 20.6% of the initial level, respectively, the labeling in the coated pit (in the zone 70–100 nm from the center) never dropped below 70.2%.

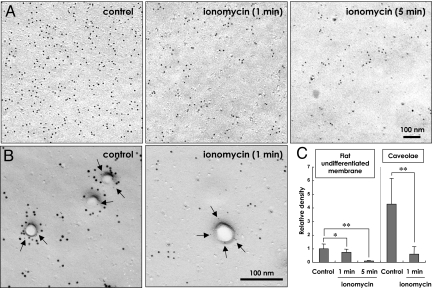

When the cell was treated with 10 μM ionomycin to increase [Ca2+]i continuously (Fig. S3), the labeling density of PI(4,5)P2 in the undifferentiated membrane was reduced to 73.8% of the control level at 1 min, and it further decreased to 9.5% at 5 min (Fig. 5 A and C). The caveolar labeling decreased faster than that in the undifferentiated membrane by ionomycin and was already reduced to 14.2% of the control level at 1 min (Fig. 5 B and C).

Fig. 5.

Labeling after ionomycin treatment. GST-PH was applied at a concentration of 30 ng/mL. (A) Representative micrographs of the PI(4,5)P2 labeling in the flat undifferentiated membrane before and 1 and 5 min after the treatment with 10 μM ionomycin. (B) Representative micrographs of the PI(4,5)P2 labeling in caveolae before and 1 min after the ionomycin treatment. PI(4,5)P2 and caveolin-1 are marked by large (10-nm) and small (5-nm) gold particles (arrows), respectively. (C) The change of the labeling intensity after the ionomycin treatment. The labeling density in the flat undifferentiated membrane of the untreated cell was taken as the standard. Twenty undifferentiated areas and 75 caveolae were randomly chosen for each time point. The labeling in caveolae, or in the zone 30–50 nm from the caveolar center, decreased significantly 1 min after the treatment, whereas that in the undifferentiated membrane showed a large decrease only at 5 min (*, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001). Caveolae were scarcely found in the 5-min sample, probably because of the structural change induced by the high [Ca2+]i.

Discussion

A Distinct Pool of PI(4,5)P2 in Caveolae.

By using a previously undescribed method, prominent concentration of PI(4,5)P2 was found in caveolae and the coated pit. On the other hand, PI(4,5)P2 in the undifferentiated flat membrane showed only a marginal degree of clustering. The clustering in the undifferentiated membrane was reduced by cholesterol depletion, but it decreased more significantly after actin depolymerization, suggesting protein involvement rather than a purely lipid-based mechanism (28).

The enrichment of PI(4,5)P2 in the detergent-resistant membrane that was observed previously (29) may be mostly due to its concentration in caveolae. We speculate that caveolins are responsible for the caveolar concentration of PI(4,5)P2. Protein domains enriched with basic residues have been hypothesized to electrostatically interact with and sequester PI(4,5)P2 (2, 5). The caveolin-scaffolding domain of caveolin-1 and caveolin-2 contains 3 basic residues (30), and a peptide of the caveolin-scaffolding domain sequesters PI(4,5)P2 in the liposomal membrane (31). Although the caveolin-scaffolding domain has fewer basic residues per molecule than other candidate proteins, such as myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS), caveolin-1 and caveolin-2 concentrate locally by forming heterooligomers and further assemble to generate the caveolar coat. One caveola was estimated to be made of 145 caveolin-1 monomers (32); moreover, they are more concentrated at the caveolar orifice than in the bulb portion (33). Thus, the local density of PI(4,5)P2 that can be sequestered by caveolins should be quite high. Moreover, phospholipase D and Rho GTPases that are reported to exist in caveolae and/or rafts (34, 35) may increase the PI(4,5)P2 production in caveolae by activating phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase locally (36).

The delayed decrease of PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae compared with the undifferentiated membrane after the Ang II stimulation may occur because PI(4,5)P2 bound to caveolins may be shielded from PLC-β1 that is activated through G proteins. The noncaveolar distribution of the AT1 receptor (37) may also contribute to the differential response. At a later time point, the caveolar PI(4,5)P2 was reduced, probably because the Ca2+ influx occurred preferentially in the vicinity of caveolae (38) and activated Ca2+-sensitive PLC-δ1 (39). The earlier decrease of PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae rather than in the undifferentiated membrane after the ionomycin treatment suggested that activation of PLC-δ1 takes place in caveolae preferentially (40, 41).

What role does the caveolar PI(4,5)P2 pool have physiologically? The activities of many ion channels and transporters are modulated by binding to PI(4,5)P2 (42) and, interestingly, many of them are concentrated in caveolae (43–49). The sequential down- and up-regulation in the noncaveolar and caveolar membranes may generate specific signals at the cell surface. Analyses with the aid of mathematical modeling may be required to understand its physiological consequence. The delayed decrease of the caveolar PI(4,5)P2 may be important in relation to other functions as well. For example, signaling cascades triggered by Ins(1,4,5)P3 and diacylglycerol would begin only late in caveolae, and this may be necessary to complete the cellular response to agonists. It is also possible that PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae may be linked to their endocytosis and/or a local cytoskeletal modulation. Some of these possibilities may be examined by using caveolin-null cells.

In contrast to caveolae, the coated pit is a transient structure. Thus, when it is morphologically visible, PI(4,5)P2 in the pit must be bound with proteins related to endocytosis, including AP-2, epsin, amphiphysin, and dynamin (50). The concentration of PI(4,5)P2 in the coated pit and its relative persistence after the Ang II stimulation are most likely caused by the engagement.

Methodological Considerations.

The present method of PI(4,5)P2 analysis has the following advantages. First, because the GST-PH probe is applied to the membrane that is physically stabilized in the replica (19), possible artifactual concerns for the GFP-PH probe (13, 14), such as artificial sequestration of PI(4,5)P2, competition with endogenous PI(4,5)P2-binding proteins, and interference by Ins(1,4,5)P3, can be precluded. Second, the method can be readily applied to any cell because exogenous protein expression is not necessary. It is particularly important to study cells in vivo for the significance of PI(4,5)P2 in highly differentiated structures and pathological conditions to be analyzed. Third, the “physical fixation” by rapid freezing and freeze-fracture imparts a high spatial-temporal resolution to the method (21). This method contrasts with the chemical fixation by aldehydes, which takes at least several seconds for a reaction and cannot fix lipid molecules. Fourth, as shown for caveolin-1 (Figs. 3A and 5B), double labeling with various proteins and lipids can be done on the same replica, which should enable evaluations of coincident localization signals for phosphoinositide-binding proteins (51).

On the other hand, there are some drawbacks to this method. First, because of the high density of PI(4,5)P2 in the cell membrane, labeling may be affected by steric hindrance among the probes, and the accurate quantification of the local PI(4,5)P2 density may be difficult. For example, PI(4,5)P2 may be more concentrated in caveolae than reflected in the density of colloidal gold particles. For an objective analysis of the distribution pattern, it is necessary to compare results obtained by different GST-PH concentrations and to use samples that show a relatively low labeling density. Second, the distance between a target PI(4,5)P2 molecule and the corresponding colloidal gold marker may be about 16 nm apart by the current 3-step labeling procedure (21). A smaller colloidal gold particle conjugated directly to either GST-PH or anti-GST antibody may be used to improve the space resolution. Third, it is difficult to selectively obtain replicas of a particular location by freeze-fracture, and this inefficiency may be an obstacle when one wishes to analyze infrequent structures.

The present study showed the presence of distinct populations of PI(4,5)P2 in caveolae and the coated pit, but in view of the multiple roles of PI(4,5)P2, other local pools of PI(4,5)P2 are likely to exist. The biased distribution of putative PI(4,5)P2-sequestering proteins—e.g., MARCKS in the filopodium and the ruffling membrane (52, 53)—suggests that differentiated membrane structures harbor these PI(4,5)P2 pools. The method described here should help in the analysis of PI(4,5)P2 distribution and behavior in various membrane structures found in differentiated cells.

Methods

Human dermal fibroblasts, mouse vas deferens, and liposomes were rapidly frozen, and freeze-fracture replicas were prepared (21). The replicas were incubated with GST-PH followed by rabbit anti-GST antibody and colloidal gold-conjugated protein A. Digital images were analyzed as described previously (21). Detailed methods are available in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. John E. Heuser (Washington University, St. Louis) for setting up the slammer instrument; Drs. Toshiki Itoh and Yasuhiro Irino (Kobe University) for advice on phosphoinositide handling; and Drs. Tsukasa Oikawa, Takeshi Ijuin (Kobe University), Kiyoko Fukami (Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences), and Nobukazu Araki (Kagawa University, Takamatsu, Japan) for the provision of reagents. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and the Global Center of Excellence Program “Integrated Molecular Medicine for Neuronal and Neoplastic Disorders” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of the Japanese government.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0900216106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin S, Wang J, Gambhir A, Murray D. PIP2 and proteins: Interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Target-specific PIP2 signalling: How might it work? J Physiol. 2007;582:967–975. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janmey PA, Lindberg U. Cytoskeletal regulation: Rich in lipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:658–666. doi: 10.1038/nrm1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaughlin S, Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: Calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botelho RJ, et al. Localized biphasic changes in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate at sites of phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1353–1368. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-rich plasma membrane patches organize active zones of endocytosis and ruffling in cultured adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9102–9123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9102-9123.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoyagi K, et al. The activation of exocytotic sites by the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate microdomains at syntaxin clusters. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17346–17352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tall EG, et al. Dynamics of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in actin-rich structures. Curr Biol. 2000;10:743–746. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rheenen J, Jalink K. Agonist-induced PIP2 hydrolysis inhibits cortical actin dynamics: Regulation at a global but not at a micrometer scale. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3257–3267. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downes CP, Gray A, Lucocq JM. Probing phosphoinositide functions in signaling and membrane trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irvine R. Inositol lipids: To PHix or not to PHix? Curr Biol. 2004;14:R308–R310. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watt SA, et al. Subcellular localization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate using the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C delta1. Biochem J. 2002;363:657–666. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rheenen J, et al. PIP2 signaling in lipid domains: A critical re-evaluation. EMBO J. 2005;24:1664–1673. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusumi A, Suzuki K. Toward understanding the dynamics of membrane-raft-based molecular interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:234–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujimoto K, Umeda M, Fujimoto T. Transmembrane phospholipid distribution revealed by freeze-fracture replica labeling. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2453–2460. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.10.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita A, Fujimoto T. Quantitative retention of membrane lipids in the freeze-fracture replica. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;128:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parton RG, Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujita A, et al. Gangliosides GM1 and GM3 in the living cell membrane form clusters susceptible to cholesterol depletion and chilling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2112–2122. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsujishita Y, et al. Specificity determinants in phosphoinositide dephosphorylation: Crystal structure of an archetypal inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase. Cell. 2001;105:379–389. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hicks SN, et al. General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu C, Watras J, Loew LM. Kinetic analysis of receptor-activated phosphoinositide turnover. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:779–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto T, Kogo H, Nomura R, Une T. Isoforms of caveolin-1 and caveolar structure. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3509–3517. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochoa GC, et al. A functional link between dynamin and the actin cytoskeleton at podosomes. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:377–389. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y, et al. PtdIns(4,5)P2 turnover is required for multiple stages during clathrin- and actin-dependent endocytic internalization. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:355–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwik J, et al. Membrane cholesterol, lateral mobility, and the phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent organization of cell actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13964–13969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336102100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pike LJ, Casey L. Localization and turnover of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in caveolin-enriched membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26453–26456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbuzova A, et al. Membrane binding of peptides containing both basic and aromatic residues. Experimental studies with peptides corresponding to the scaffolding region of caveolin and the effector region of MARCKS. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10330–10339. doi: 10.1021/bi001039j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wanaski SP, Ng BK, Glaser M. Caveolin scaffolding region and the membrane binding region of SRC form lateral membrane domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42:42–56. doi: 10.1021/bi012097n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parton RG, Hanzal-Bayer M, Hancock JF. Biogenesis of caveolae: A structural model for caveolin-induced domain formation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:787–796. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorn H, et al. Cell surface orifices of caveolae and localization of caveolin to the necks of caveolae in adipocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3967–3976. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czarny M, Lavie Y, Fiucci G, Liscovitch M. Localization of phospholipase D in detergent-insoluble, caveolin-rich membrane domains. Modulation by caveolin-1 expression and caveolin-182–101. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2717–2724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michaely PA, Mineo C, Ying YS, Anderson RG. Polarized distribution of endogenous Rac1 and RhoA at the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21430–21436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doughman RL, Firestone AJ, Anderson RA. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases put PI4,5P2 in its place. J Membr Biol. 2003;194:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-2027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wyse BD, et al. Caveolin interacts with the angiotensin II type 1 receptor during exocytic transport but not at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23738–23746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isshiki M, Anderson RG. Function of caveolae in Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ -dependent signal transduction. Traffic. 2003;4:717–723. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen V, et al. Regulation of inositol lipid-specific phospholipase cdelta by changes in Ca2+ ion concentrations. Biochem J. 1997;327:545–552. doi: 10.1042/bj3270545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke CJ, et al. Phospholipase C-delta1 modulates sustained contraction of rat mesenteric small arteries in response to noradrenaline, but not endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H826–H834. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01396.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaga M, et al. A PLCdelta1-binding protein, p122/RhoGAP, is localized in caveolin-enriched membrane domains and regulates caveolin internalization. Genes Cells. 2004;9:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: How and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin J, et al. The regulation of the cardiac potassium channel (HERG) by caveolin-1. Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;86:405–415. doi: 10.1139/o08-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martens JR, et al. Isoform-specific localization of voltage-gated K+ channels to distinct lipid raft populations. Targeting of Kv1.5 to caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8409–8414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bossuyt J, Taylor BE, James-Kracke M, Hale CC. Evidence for cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger association with caveolin-3. FEBS Lett. 2002;511:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujimoto T. Calcium pump of the plasma membrane is localized in caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1147–1157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujimoto T, et al. Localization of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-like protein in plasmalemmal caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lockwich TP, et al. Assembly of Trp1 in a signaling complex associated with caveolin-scaffolding lipid raft domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11934–11942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Torihashi S, Fujimoto T, Trost C, Nakayama S. Calcium oscillation linked to pacemaking of interstitial cells of Cajal: Requirement of calcium influx and localization of TRP4 in caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19191–19197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haucke V. Phosphoinositide regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1285–1289. doi: 10.1042/BST0331285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlton JG, Cullen PJ. Coincidence detection in phosphoinositide signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen A, et al. Activation of protein kinase C results in the displacement of its myristoylated, alanine-rich substrate from punctate structures in macrophage filopodia. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1211–1215. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myat MM, Anderson S, Allen LA, Aderem A. MARCKS regulates membrane ruffling and cell spreading. Curr Biol. 1997;7:611–614. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.