Abstract

Nematode parasitism is a worldwide health problem resulting in malnutrition and morbidity in over 1 billion people. The molecular mechanisms governing infection are poorly understood. Here, we report that an evolutionarily conserved nuclear hormone receptor signaling pathway governs development of the stage 3 infective larvae (iL3) in several nematode parasites, including Strongyloides stercoralis, Ancylostoma spp., and Necator americanus. As in the free-living Caenorhabditis elegans, steroid hormone-like dafachronic acids induced recovery of the dauer-like iL3 in parasitic nematodes by activating orthologs of the nuclear receptor DAF-12. Moreover, administration of dafachronic acid markedly reduced the pathogenic iL3 population in S. stercoralis, indicating the potential use of DAF-12 ligands to treat disseminated strongyloidiasis. To understand the pharmacology of targeting DAF-12, we solved the 3-dimensional structure of the S. stercoralis DAF-12 ligand-binding domain cocrystallized with dafachronic acids. These results reveal the molecular basis for DAF-12 ligand binding and identify nuclear receptors as unique therapeutic targets in parasitic nematodes.

Keywords: dafachronic acid, parasitology, pharmacology, X-ray crystal structure

Parasitic nematodes constitute a large family of pathogens that infect hosts ranging from plants and animals to people, causing great economic loss and worldwide health threats (1, 2). One of the most problematic parasites, Strongyloides stercoralis, is estimated to infect 100–200 million people. Primary infections are often asymptomatic and clinically silent in immunocompetent individuals. However, once the immune system is compromised (e.g., by corticosteroid therapy), the parasite establishes autoinfection cycles that result in a frequently fatal disseminated strongyloidiasis (3, 4). Hookworms (Ancylostoma and Necator spp.) are other parasitic nematodes that affect >1 billion people and are the dominant cause for iron-deficient anemia worldwide (2). Oral administration of anthelmintics such as benzimidazoles (microtuble toxins) and ivermectin (a neurotoxin) is currently the preferred treatment for nematode infections (5). However, no reliable options exist for treating the more severe form of disseminated strongyloidiasis (6). Moreover, resistance to the anthelmintics has become widespread in animals and is beginning to occur in humans (2, 7). Therefore, studying the mechanisms that govern nematode life cycles is an attractive approach to identifying new therapeutic targets.

Infection of hosts by parasitic nematodes is mediated by infective larvae, which in S. stercoralis and hookworm are the third stage or L3 larvae (iL3) (4, 5). Interestingly, iL3 larvae resemble the dauer larvae of the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans in that they are all nonfeeding, developmentally arrested, dormant filariform larvae with a sealed buccal capsule and thickened body wall cuticle, enabling them to survive environmental challenges (8). Like C. elegans dauer larvae, iL3 recover from their arrested development once they enter a proper environment (i.e., their respective hosts) (9). To date, the molecular mechanisms controlling the recovery of iL3 parasites are poorly understood.

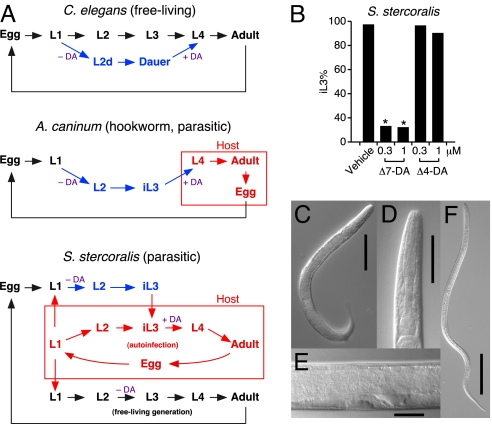

In C. elegans, dauer diapause is controlled by endocrine signals in response to environmental cues. In favorable environments, reproductive development requires an insulin/IGF-1 (II-S) and TGFβ signaling network that converges on a downstream steroid hormone–nuclear receptor signaling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor DAF-12 (10). Previously, we have shown that steroid hormones named dafachronic acids (DAs), which are de novo synthesized from dietary sterols by the cytochrome P450 DAF-9, activate DAF-12 and promote dauer recovery in C. elegans (11). For parasitic nematodes, it has also been reported that the induction by the host of the II-S pathway is essential for iL3 recovery (12, 13). Based on the similarities between free-living and parasitic worms, we hypothesized that the steroid hormone/nuclear receptor signal (i.e., DA/DAF-12) would also be conserved and control the dauer-like iL3 diapause in parasitic nematodes (Fig. 1A). In the present study, we identified the DAF-12 orthologs in several parasitic species and showed that these receptors respond to DAs. Remarkably, administration of DAs caused a significant proportion of worms in the postfree-living generation of S. stercoralis to form supernumerary free-living but unviable stage 4 larvae. There was a corresponding and profound reduction in the population of the pathogenic S. stercoralis iL3, suggesting that these compounds or their congeners might be used as a new class of drugs for treatment of disseminated strongyloidiasis. Finally, we report the X-ray crystal structure of the DAF-12 ligand-binding domain for S. stercoralis. The structural basis for ligand binding to DAF-12, which represents one of the hundreds of nuclear receptors found in nematodes, should provide a powerful tool for drug development.

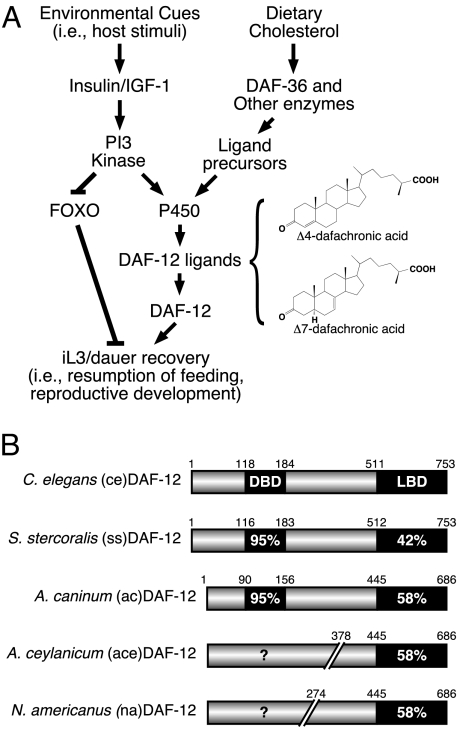

Fig. 1.

Conserved nuclear receptor signaling pathway controls dauer/iL3 diapause. (A) Schematic for signaling pathways that control dauer/iL3 diapause. The chemical structures for dafachronic acid ligands for DAF-12 are also shown. (B) Sequence similarities of DAF-12 homologues in parasitic nematodes. DAF-12 aa positions in the partial A. ceylanicum and N. americanus cDNA clones were assigned according to their homologous positions in A. caninum.

Results

DAF-12 Homologues in Parasitic Nematodes.

Based on the hypothesis that iL3 and dauer represent homologous stages in nematode development (Fig. 1A), we investigated whether iL3 diapause is regulated by a DAF-12-like nuclear receptor. We analyzed the parasitic nematode genome database (www.nematode.net) and subsequently cloned full-length cDNAs encoding DAF-12 orthologs from S. stercoralis (14) (ssDAF-12) and the dog hookworm Ancylostoma caninum (acDAF-12). We also cloned partial cDNAs encoding aa 378–686 of the panspecific hookworm Ancylostoma ceylanicum DAF-12 ligand-binding domain (aceDAF-12) and aa 274–686 of the human hookworm Necator americanus (naDAF-12). These cDNAs shared significant identities with C. elegans DAF-12 (ceDAF-12) in their corresponding DNA and ligand-binding domains (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). Notably, all of the parasitic DAF-12s exist in iL3 cDNA libraries, indicating their physiological expression in the dauer-like larvae.

Parasite DAF-12s Are Activated by DAs.

We tested whether Δ4-DA and Δ7-DA can activate the parasitic DAF-12s in a fashion similar to that observed with C. elegans DAF-12 (11). We found both Δ4- and Δ7-DAs activated Gal4-DAF-12 chimeras when tested in cell-based cotransfection assays (Fig. 2 A–C). Full-length hookworm acDAF-12 was also able to induce reporter gene expression driven by a promoter containing DAF-12 response elements from the lit-1 kinase promoter (15), showing that the DNA-binding domain is functional (Fig. 2D). Unlike the hookworm DAF-12 constructs, the corresponding S. stercoralis DAF-12 does not express well in mammalian cells. Therefore, we generated an alternative chimeric expression construct in which the N terminus of ceDAF-12 (including the DNA-binding domain) was fused to the C-terminal ligand-binding domain of ssDAF-12. This hybrid receptor (cessDAF-12) is expressed in cell culture and was capable of robust activation of the lit-1 kinase reporter by both DAs (Fig. 2E). The EC50 for activation of the parasite DAF-12s ranged from 25–147 nM for Δ7-DA and 130–294 nM for Δ4-DA. This rank order of potency is similar to that observed for ceDAF-12 (16). Importantly, activation by DAs could be abolished by mutating the conserved arginine that has been shown to be critical for ligand activation in ceDAF-12 (Fig. 2E and ref. 11). We also used a mammalian 2-hybrid assay to monitor the interaction between the parasite DAF-12s and the receptor interaction domains of the coactivator SRC-1 (SRC1-ID4) and the corepressor Din-1S (Din-1S RID, identified in Fig. S2). As predicted, upon DA treatment the interaction with Din-1S is compromised and that with SRC-1 is induced (Fig. 2 F–H).

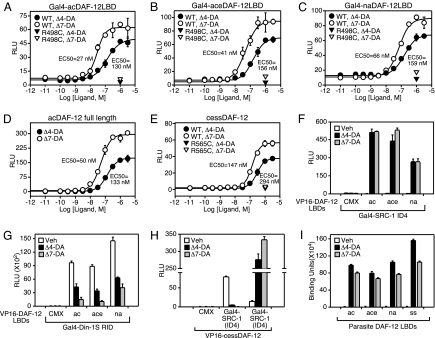

Fig. 2.

Parasite DAF-12s are activated by dafachronic acids. (A–E) Ligand activation of parasite DAF-12 homologues and various ligand binding mutants. (F–H) Mammalian 2-hybrid assay for ligand-dependent interaction between parasite DAF-12s and coactivator (SRC-1 ID4) or corepressor (Din-1S RID) interaction domains. Cotransfection assays were performed in HEK293 (A–C and F–H) or CV-1 (D and E) cells. RLU, relative light units. (I) In vitro ligand binding of DAs to parasite DAF-12 ligand-binding domains as monitored by ligand-induced association of the coactivator LXXLL motif (SRC1–4) with receptor. One micromolar of DA was used in F–I. n = 3 ± SD.

Finally, to prove that DAs directly bind parasitic DAF-12s, we used an in vitro ligand-binding assay that detects agonist-induced interactions between receptor and coactivator peptides containing the LXXLL motif (11). We found that both Δ4-DA and Δ7-DA bind directly to all parasitic DAF-12s (Fig. 2I), providing unequivocal evidence that DAs act as classical nuclear receptor ligands.

DAF-12 Ligand-Binding Domain Structure.

To provide insight into the biochemistry and pharmacology of DAF-12 ligand binding, we solved the X-ray crystal structure of the ssDAF-12 ligand-binding domain complexed with a coactivator LXXLL peptide and both DAs (Fig. 3A and Table S1). The overall architecture of the ssDAF-12 ligand-binding domain is similar to other members of the nuclear receptor family (17). It consists of 13 α-helices and 3 β-sheets, which are packed in a 3-layer α-helical sandwich to create a ligand-binding pocket where DAs are embedded (gray structures). Instead of having a characteristic loop between helices (H) 7 and 8, a unique feature of ssDAF-12 is a short H7′ α-helix (yellow in Fig. 3 A). The ssDAF-12 ligand-binding domain contains a typical nuclear receptor activation function-2 helix (AF-2) that adopts a characteristic “active” conformation (shown in pink) as a consequence of its interaction with the coactivator LXXLL peptide (SRC1–4 shown in red, Fig. 3A).

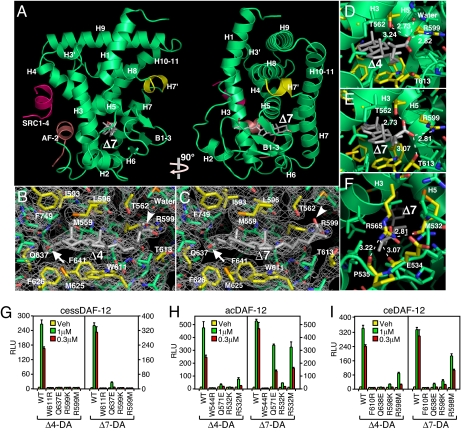

Fig. 3.

X-ray crystal structure of DAF-12 ligand-binding domain. (A) Ribbon model reveals the overall architecture of the ssDAF-12 ligand-binding domain (green) complexed with Δ7-DA (gray) and the SRC1 coactivator peptide (red). The AF-2 helix is shown in pink. (B and C) Electron density maps of the ssDAF-12 ligand binding pocket bound to Δ4-DA (B) or Δ7-DA (C). Carboxyls (arrowheads) and 3-ketos (arrows) of DA are shown. (D and E) H-bonding of ssDAF-12 aa directly involved in binding the C27-carboxyl group of Δ4-DA (D) or Δ7-DA (E). (F) The “lid” of the ligand binding pocket is formed by H-bond clamping between yellow-colored side-chain (R565) and main-chain oxygen atoms of M532, E534, and P535. H-bonds are illustrated by white dashed lines with bond lengths noted in Å. (G–I) Site-directed mutagenesis reveals differential ligand binding mechanisms for ssDAF-12 (G), acDAF-12 (H), and ceDAF-12 (I). Cotransfection assays were performed in CV-1 cells with the indicated receptors and a DAF-12 responsive reporter gene as in Fig. 2D. n = 3 ± SD.

As in mammalian nuclear receptors that bind steroid hormones, the ligand-binding pocket of ssDAF-12 is relatively small (517Å3 for Δ4-DA and 548 Å3 for Δ7-DA), consistent with the high specificities and affinities of ligand binding. Within the pocket, the lipophilic steroidal rings of DAs are surrounded by nonpolar residues (Fig. 3 B and C, shown in yellow), which create a hydrophobic environment critical for the binding of DAs. As evidenced experimentally, introducing a single charged residue (W611R) eliminated receptor activation (Fig. 3G). The 2 polar groups of DAs are also determinants for ligand recognition: Oxygen atoms from the C3-ketone (arrow) and the C27 carboxyl groups (arrowhead) accept hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) donated by polar side chains of various residues in Fig. 3 B and C. Disrupting the H-bonds by either mutating the side chains (Q637E and R599K/M in Fig. 3G) or by using DA precursors that lack the C27 carboxyl-groups (Fig. S3) compromised receptor activation. It is noteworthy that the C27 carboxyl group of Δ7-DA forms 3 H-bonds with ssDAF-12 whereas the C27 carboxyl group of Δ4-DA only forms 2 H-bonds (a third H-bond is formed with a water molecule) of weaker strength as indicated by the longer bond lengths with T562 and R599 (Fig. 3 D and E). This difference may help explain why Δ4-DA is a less potent ligand. However, because Δ4-DA is also less efficacious than Δ7-DA under every conditioned examined, effects other than the ligand's affinity may contribute to the receptor's response to different ligands.

Residues outside of the pocket also contribute to ligand binding. Mutation of an arginine conserved in all DAF-12s (R565 in Fig. 3F) disrupted DAF-12 activation by DAs (Fig. 2 A–E, and ref. 11). Although this residue in ssDAF-12 does not interact with DAs directly, it stabilizes ligand binding by forming H-bonds with the loop region that crosses over the pocket opening (Fig. 3F), thereby functioning as a “lid” to capture the ligand.

Next, we addressed whether the mechanism of ligand binding revealed in the ssDAF-12 structure is conserved in other DAF-12s. In addition to the conserved arginine that is essential for DA activation (Fig. 2 A–E), residues involved in ligand recognition are conserved in all DAF-12s (Fig 3 A–F and Fig. S1). As in ssDAF-12, introducing a single charge into a hydrophobic residue in the core of the pocket (W611R in ssDAF-12, W544R in acDAF-12, F610R in ceDAF-12) abolished receptor activation in all DAF-12s when analyzed in a cotransfection assay (Fig. 3 G–I). However, disruption of residues involved in H-bonding impaired receptor activation in a species-specific manner (compare ssDAF-12 residues Q637E and R599K/M in Fig. 3G to homologous acDAF-12 residues Q571E and R532K/M in Fig. 3H, and ceDAF-12 residues Q638E and R598K/M in Fig. 3I). These findings indicate that DAF-12s bind with DAs through mechanisms that, although similar, also have distinct pharmacological properties.

DAF-12 Activation Induces iL3 Recovery.

DAs induce dauer recovery in C. elegans by activating DAF-12 (11). Therefore, we tested whether DAF-12 activation in parasitic nematodes has similar effects. Resumption of feeding is a hallmark for iL3 larvae to recover from the dauer-like stage when they enter their host. This developmental reactivation can be induced experimentally by providing serum with glutathione (GSH) or S-methyl glutathione (GSM) and working through a mechanism that stimulates the II-S pathway (9, 12, 13). When tested on the iL3 stage of 2 hookworm species and S. stercoralis, the 2 DAs induced all of these parasitic larvae to start feeding in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S4). In contrast, 4-cholesten-3-one and lathosterone, the metabolic precursors of Δ4- and Δ7-DA that do not activate DAF-12, failed to do so. For Ancylostoma spp., a further sign of host-induced iL3 recovery is the secretion of proteins (ASP-1 and ASP-2) that interact with the host's immune system (18, 19). As shown in Fig. 4C, DAs stimulated the secretion of the pathogenesis-related proteins that are also induced upon treatment with serum and GSH. These results demonstrate that DAF-12 is a key molecular switch that initiates development in parasitic nematodes.

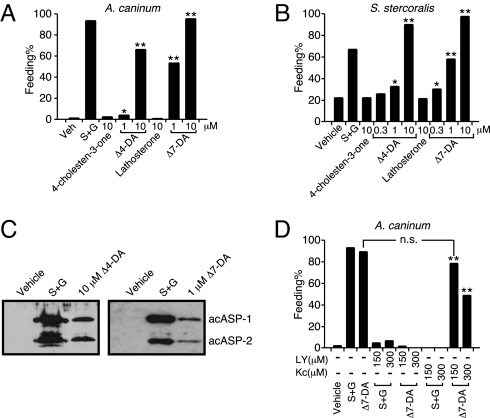

Fig. 4.

DAF-12 activation induces iL3 recovery. (A and B) Dafachronic acids stimulate resumption of feeding in iL3 of A. caninum, (n = 250–1,200) (A), and S. stercoralis, n = 725–1,081 (B). (C) Dafachronic acids stimulate ASP secretion by A. caninum iL3 larvae. (D) Effects of PI3-kinase and P450 inhibitors on Δ7-DA induced feeding in A. caninum iL3 larvae (n = 100–407). S+G, 10% canine serum plus 15 mM GSM (A, C, and D) or 5 mM GSH (B); LY, PI3-kinase inhibitor LY249002; Kc, P450 inhibitor ketoconazole; *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.0001; n.s., not significant; χ2 2-tailed test, all compared with vehicle treatment unless indicated. Experiments were repeated 2 times (D) or 4 times (A and B) with similar results.

In C. elegans, the cytochrome P450 DAF-9 is required for environmental stimuli to induce dauer recovery. To test whether a similar pathway exists in parasitic nematodes, we used ketoconazole, a broad-spectrum inhibitor for P450s that is known to block steroid hormone synthesis in mammals (20). Ketoconazole completely abolished iL3 recovery induced by serum/GSM and this inhibition was overcome by pharmacological supplementation of Δ7-DA (Fig. 4D), suggesting that a P450 is required for parasitic nematodes' response to host stimuli. Although to date we have been unable to isolate a DAF-9 homolog from any of the parasitic nematodes, in A. caninum we discovered a partial cDNA encoding a homolog of DAF-36 (Fig. S5), a rieske-oxygenase that in C. elegans is required for generation of the endogenous ligand Δ7-DA (21).

Interestingly, DA did not restore iL3 recovery when the II-S pathway was inhibited by a PI3-kinase inhibitor (LY in Fig. 4D), implying that, as in C. elegans, other outputs from II-S—such as FOXO proteins—collaborate with DAF-12 to achieve iL3 regulation (11). These data support the hypothesis that a conserved steroid hormone/nuclear receptor signaling pathway controls dauer/iL3 recovery in both C. elegans and parasitic nematodes (Fig. 1A).

Δ7-DA Blocks iL3 Larval Development.

In addition to stimulating dauer recovery when bound by ligands, DAF-12 is required for entry into dauer when it is not bound to ligand by acting as a transcriptional repressor of target genes that favor reproductive development (10, 22). We tested whether loss of this repression by activating DAF-12 early in development of parasitic nematodes would impair iL3 formation. Unlike hookworm, whose progenies directly develop into iL3 larvae in each generation, S. stercoralis has an alternative, indirect route in which one generation of the free-living life cycle is completed before iL3 progenies are formed (Fig. 5A). This unique feature of S. stercoralis permitted us to obtain synchronized parasite populations for testing. Remarkably, when progenies of the free-living generation of S. stercoralis were treated with Δ7-DA, 88% of the parasites failed to develop into filariform iL3 larvae compared with only 3% when treated with vehicle (Fig. 5B). Importantly, this population of DA-treated larvae developed instead into rhabditiform, molting-defective larvae (Fig. 5 C–E), which, under continuous exposure to exogenous DA, died within a few days (Table S2). The inability of Δ7-DA to fully rescue the iL3 stage is consistent with its partial agonist activity on ssDAF-12 relative to ceDAF-12 (Fig. S6). Interestingly, Δ4-DA had no significant effect on reducing the iL3 population, consistent with the finding that it has even weaker DAF-12 agonist activity (Fig. 2E and Fig. S6). These findings suggest that Δ7-DA or a similar congener may have therapeutic utility in the treatment of disseminated strongyloidiasis by preventing iL3 development and therefore terminating the life cycle of S. stercoralis. From an evolutionary standpoint, differential regulation of development by DAF-12 orthologs and their dafachronic acid ligands in free-living nematodes such as C. elegans, in strongyloid species with alternate free living cycles, and in obligate parasites such as hookworms that lack free-living life-cycle alternatives, may recapitulate biochemical adaptations that have occurred during the evolution of parasitism in the nematodes.

Fig. 5.

Δ7-DA inhibits iL3 development in S. stercoralis. (A) Comparative life cycles of free-living and parasitic nematode species. (B) Effects of DAs on iL3 formation in S. stercoralis. n = 113–474; *, P < 0.0001; χ2 2-tailed test, all compared with vehicle treatment. Experiments were repeated 4 times with similar results. (C–E) Δ7-DA treatment during early development results in molting-defective, rhabditiform L3/L4 S. stercoralis larvae. (F) Image of an untreated iL3 S. stercoralis larva. Note the difference in morphology between this filariform larva and the Δ7-DA treated larvae in C–E. Scale bars, 100 μm in C and F; 50 μm in D; and 20 μm in E.

Discussion

In the life cycle of parasitic nematodes, recovery of the dauer-like, iL3 larvae after host infection is a poorly understood but essential developmental process. Previous work has shown that successful infection is governed by a variety of host stimuli, including temperature, CO2 concentration, and serum (9). All of these factors require an insulin-like signaling pathway referred to as II-S (12, 13); however, the downstream transducers of this pathway have not been identified (12, 13). In the present study, we describe the existence of a conserved steroid hormone signaling pathway in parasitic nematodes that is mediated by the nuclear receptor DAF-12 and controls the progression of the parasite's infectious stage, a process that is homologous to C. elegans dauer recovery. As part of this study, we identified the C. elegans orthologs of DAF-12 in several parasitic nematodes and showed that they bind DA ligands, which in turn stimulate iL3 recovery. Furthermore, we showed DAF-12 activation rescues the serum-induced iL3 recovery that is impaired by P450 inhibition, supporting the notion that within parasitic nematodes, as in C. elegans, P450s are involved in the production of DAF-12 ligands and are under the regulation of the insulin-like, II-S-signaling pathway. Moreover, we characterized the 3-dimensional structure of the ssDAF-12 ligand-binding domain and thereby showed the biophysical basis for ligand activation. Our work is consistent with a recent study showing that this hormonal control of dauer/iL3 diapause also exists in other nematode species (23).

From a pharmacological perspective, several aspects of the parasitic DAF-12 pathway are worth highlighting. First, despite the conservation of the pathway with C. elegans and their ability to respond to DAs, parasitic DAF-12 orthologs are not identical among species but share between 42% and 58% similarity in their ligand-binding domains. These differences likely explain the higher concentrations required for Δ4-DA and Δ7-DA activation of parasite versus C. elegans DAF-12. The sequence differences in the various DAF-12 ligand-binding domains and their relative affinities for Δ4-DA and Δ7-DA suggest that the physiologic ligands for parasite DAF-12s may also vary slightly from species to species. Further support for this notion comes from our inability to identify sequence homologs of the P450 enzyme DAF-9 in the current parasite gene databases or by low-stringency cDNA screening efforts. Interestingly, we were able to identify in A. caninum a homolog of DAF-36, one of the enzymes required for synthesis of a DAF-9 substrate that is the immediate precursor to Δ7-DA (21). This observation raises the intriguing possibility that parasites lack DAF-9 altogether. One interpretation of this finding would suggest that parasitic nematodes are unable to complete the terminal enzymatic step in DAF-12 ligand synthesis autonomously and instead must rely on a host-specific enzyme for this purpose. Although it remains to be proven, this hypothesis provides an attractive explanation as to why host-specific factors are required for iL3 recovery.

A second discovery from this work that has important pharmacologic implications is the ability of Δ7-DA to dramatically reduce the iL3 population in S. stercoralis. As observed during dauer recovery in C. elegans, DAF-12 activation in both S. stercoralis and hookworm mediated iL3 recovery. However, as a weak agonist for parasite DAF-12s, Δ7-DA did not commit the nematode to a complete recovery of its reproductive development but instead resulted in molting-defective larvae that terminated the parasite's lifecycle. A similar effect of partial DAF-12 activation was also observed during C. elegans dauer rescue when using low doses of DAs (Fig. S7 and ref. 11). These findings provide a strong therapeutic rationale for using selective DAF-12 modulators to block iL3 recovery, a strategy that would be strikingly similar to the use of selective estrogen and progesterone modulators in oral contraception.

A clear example of the therapeutic need that would be fulfilled from successfully targeting DAF-12 is disseminated strongyloidiasis. This frequently lethal form of the disease is caused by an autoinfection cycle in which S. stercoralis never leaves its host (Fig. 5A), and in immunocompromised individuals, this allows a rapid amplification of the parasites that results in subsequent multiorgan failure (4). Once infected, individuals may carry the parasite for the rest of their lives despite aggressive treatments. Thus far, ivermectin is the choice drug that has been successful in reducing iL3 hyperinfections. However, satisfactory treatments of disseminated strongyloidiasis have not been established in humans, mainly because available drugs have little effect on the autoinfective larvae (6). Our study suggests that selective ligand modulators of DAF-12 might be used to stop iL3 larvae progression during autoinfection. Taken together, our work provides the first biological, pharmacological, and structural characterization of a nuclear receptor pathway in parasitic species and thereby serves as the basis for a new therapeutic approach to treating a spectrum of parasitic diseases that collectively affect more than 1 billion people worldwide.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Dafachronic acids were made as described in ref. 16. Δ7-dafachronic acid was also obtained as a gift from Dr. E. J. Corey (Harvard University, Boston) (24). Lathosterone and 4-cholesten-3-one were purchased from Research Plus Inc. We obtained 5-cholesten-3-one from Sigma.

cDNA and Plasmids.

acDAF-12 and naDAF-12 cDNAs were isolated from iL3 libraries of A. caninum and N. americanus; aceDAF-12LBD cDNA was obtained from the Genome Sequencing Center, Washington University School of Medicine (database accession number pk90d07); ssDAF-12 was a gift from Dr. Afzal Siddiqui (East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN) (National Center for Biotechnology Information accession number, AF145048) (14). cDNAs were PCR-amplified and inserted into the indicated expression vectors and verified by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Reporter Assays.

HEK293 and CV-1 cells were cultured and transfected in 96-well plates as described (11, 16) by using 50 ng luciferase reporter, 10 ng CMX-β-galactosidase reporter, 15 ng nuclear receptor expression plasmids, and 15 ng empty vector or cofactor expression plasmids. Ethanol or indicated compounds were added to each well 8 h posttransfection, incubated for 16 h, and cells were then harvested for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities as described. In Fig. 1E, Fig. 3G, and Fig. S6, 15 ng of the coactivator GRIP-1 was coexpressed to increase the signal. Data represent the mean ± SD from triplicate assays and were plotted by using Sigma Plot software.

Ligand Binding Assay.

Parasite DAF-12 ligand-binding domains were expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells as 6X His-GST fusion proteins. Ligand bindings were determined by Alpha screening assay kit (Perkin-Elmer). The experiments were conducted with ≈40 nM receptor ligand-binding domain and 10 nM of biotinylated SRC1–4 peptide (QKPTSGPQAQQKSLLQQLLTE) in the presence of 20 μg/mL donor and acceptor beads in a buffer containing 50 mM Mops, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM CHAPS, and 0.1 mg/mL BSA, all adjusted to a pH of 7.4.

Structural Studies.

X-ray crystallography methods are described in the SI Materials and Methods. The structures reported in this work have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank at the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do).

Other Methods.

In vitro and in vivo parasite studies, ASP secretion assay, and protein purification are described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank L. Avery and D. Russell for helpful discussion; Dr. Afzal Siddiqui for ssDAF-12 cDNA; the Genome Sequencing Center of Washington University of St. Louis for aceDAF-12 cDNA; Dr. E. J. Corey for Δ7-dafachronic acid; and Y. Li, J. Lai, S. Kruse, and R. Talaski for participating in the early phase of the DAF-12 expression and crystallization trials. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.J.M.); the Robert A. Welch Foundation (D.J.M., S.A.K., and R.J.A.); the Jay and Betty Van Andel Foundation (H.E.X.); and National Institutes of Health Grants U19DK62434 (to D.J.M.), AI062857 and AI069293 (to J.M.H.), AI50688 and AI22662 (to J.B.L.), and DK071662, DK066202, and HL089301 (to H.E.X.). The X-ray data were collected by the General Medicine and Cancer Institutes Collaborative Access Team, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute Grant Y1-CO-1020 and the National Institute of General Medical Science Grant Y1-GM-1104. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357. D.J.M. is an investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2008.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The structure factors and atomic coordinates discussed in this work have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 3GYT (Δ4-DA) and 3GYU (Δ7-DA)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0904064106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jasmer DP, Goverse A, Smant G. Parasitic nematode interactions with mammals and plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052102.104023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez PJ, et al. New technologies for the control of human hookworm infection. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Igra-Siegman Y, et al. Syndrome of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:397–407. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viney ME, Lok JB The C. elegans Research Community, editor. Strongyloides spp. WormBook. 2007. doi/ 10.1895/wormbook.1.141.1, http://www.wormbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller R. In: Worms and Human Disease. Muller R, editor. New York: CABI; 2002. pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox LM. Ivermectin: Uses and impact 20 years on. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:588–593. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328010774c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan RM. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: A status report. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotez P, Hawdon J, Schad GA. Hookworm larval infectivity, arrest and amphiparatenesis: The Caenorhabditis elegans daf-c paradigm. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90159-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawdon JM, Schad GA. Serum-stimulated feeding in vitro by third-stage infective larvae of the canine hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. J Parasitol. 1990;76:394–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antebi A The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. 2006. Nuclear hormone receptors in C. elegans. doi/ 10.1895/wormbook.1.64.1, http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motola DL, et al. Identification of ligands for DAF-12 that govern dauer formation and reproduction in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;124:1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tissenbaum HA, et al. A common muscarinic pathway for diapause recovery in the distantly related nematode species Caenorhabditis elegans and Ancylostoma caninum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:460–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brand A, Hawdon JM. Phosphoinositide-3-OH-kinase inhibitor LY294002 prevents activation of Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma ceylanicum third-stage infective larvae. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:909–914. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui AA, Stanley CS, Skelly PJ, Berk SL. A cDNA encoding a nuclear hormone receptor of the steroid/thyroid hormone-receptor superfamily from the human parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasitol Res. 2000;86:24–29. doi: 10.1007/pl00008502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shostak Y, Van Gilst MR, Antebi A, Yamamoto KR. Identification of C. elegans DAF-12-binding sites, response elements, and target genes. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2529–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.1218504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma KK, et al. Synthesis and activity of dafachronic acid ligands for the C. elegans DAF-12 nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:640–648. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourguet W, et al. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding domain of the human nuclear receptor RXRα. Nature. 1995;375:377–382. doi: 10.1038/375377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawdon JM, Narasimhan S, Hotez PJ. Ancylostoma secreted protein 2: Cloning and characterization of a second member of a family of nematode secreted proteins from Ancylostoma caninum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:149–165. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawdon JM, Jones BF, Hoffman DR, Hotez PJ. Cloning and characterization of Ancylostoma-secreted protein. A novel protein associated with the transition to parasitism by infective hookworm larvae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6672–6678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonino N. The use of ketoconazole as an inhibitor of steroid production. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:812–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rottiers V, et al. Hormonal control of C. elegans dauer formation and life span by a Rieske-like oxygenase. Dev Cell. 2006;10:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludewig AH, et al. A novel nuclear receptor/coregulator complex controls C. elegans lipid metabolism, larval development, and aging. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2120–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.312604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogawa A, Streit A, Antebi A, Sommer R. A conserved endocrine mechanism controls the formation of dauer and infective larvae in nematodes. Curr Biol. 2009;19:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giroux S, Corey EJ. Stereocontrolled synthesis of dafachronic acid A, the ligand for the DAF-12 nuclear receptor of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9866–9867. doi: 10.1021/ja074306i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.