Abstract

Intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract is an uncommon occurrence, with the majority being localized to the esophagus or duodenum. Hematoma of the gastric wall is very rare, and has been described most commonly in association with coagulopathy, peptic ulcer disease, trauma, and amyloid-associated microaneurysms. A case of massive gastric intramural hematoma, secondary to anticoagulation therapy, and a gastric ulcer that was successfully managed with conservative therapy, is presented. A literature review of previously reported cases of gastric hematoma is also provided.

Keywords: Anticoagulation, Gastrointestinal bleeding, Gastric intramural hematoma, Gastric ulcer, Hematoma, Peptic ulcer disease

Abstract

L’hématome intramural du tube digestif est peu courant, la majorité des cas se situant dans l’œsophage ou le duodénum. L’hématome de la paroi gastrique est très rare et a surtout été décrit en association avec une coagulopathie, un ulcère gastroduodénal, un traumatisme ou un microanévrisme associé à des substances amyloïdes. Est présenté un cas d’hématome intramural gastrique massif, secondaire à la prise d’anticoagulants et à un ulcère gastroduodénal bien pris en charge par un traitement classique. Une analyse bibliographique des cas d’hématomes intramuraux gastriques déjà déclarés est également présentée.

Intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract is an uncommon disorder (1). Most of these hematomas are localized either in the esophagus or in the duodenum. They can be idiopathic in nature (2) or they can result from endoscopic therapy (3,4), coagulopathy (5,6), peptic ulcer disease, trauma (7) or repeated vomiting (8). Hematoma of the stomach wall is rare, and only a few case reports describe this condition (8). A case of a gastric hematoma successfully managed with conservative therapy is presented.

CASE PRESENTATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

A 69-year-old man was admitted to a community hospital where he was treated for five days for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia. While in the hospital, the patient developed hematemesis, and his hemoglobin dropped to 44 g/L. Due to absence of emergent transfusion capacity and an endoscopic facility, the patient was transferred to the University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta. While at the community hospital, the patient provided a history of intermittent black stools for the past three weeks. There was no history of abdominal pain, previous gastrointestinal bleeding, changes in bowel habit or constitutive symptoms. There was no history of liver disease. Medical history was significant for abdominal aortic aneurysm repaired by endovascular graft one year previously (the exact site of the graft was not known at this point), peripheral vascular disease, previous stroke, hypertension, dyslipidemia, alcohol abuse, chronic renal failure with a baseline serum creatinine of 250 μmol/L, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gout, cellulitis of the left foot and gastroesophageal reflux. Current medications included warfarin, clopidogrel, acetylsalicylic acid, lisinopril, amlodipine, lansoprazole, imovane, lorazepam, albuterol, atorvastatin, multivitamin and ferrous gluconate.

On arrival, the patient was hemodynamically unstable, requiring intubation, intravenous fluids and packed red blood cells. Cardiovascular examination was within normal limits except for bilateral crackles at both lung bases. Abdominal examination was unremarkable. There were no signs of peritonitis or chronic liver disease. A digital rectal examination revealed occult blood-positive feces.

Laboratory investigations were remarkable except for a white blood cell count of 12.3×109/L, neutrophils 10.8×109/L, platelet count 185×109/L, partial thromboplastin time of 31 s, international normalized ratio of 2.5, creatinine 263 μmol/L and urea 33.7 mmol/L.

Five units of packed red blood cells raised the patient’s hemoglobin from 44 g/L to 76 g/L. Two units of fresh frozen plasma, 10 mg of vitamin K and desmopressin were provided to reverse coagulopathy. Intravenous pantoprazole and octreotide were initiated for a presumed upper gastrointestinal bleed of unknown origin. After initial resuscitation, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for further management.

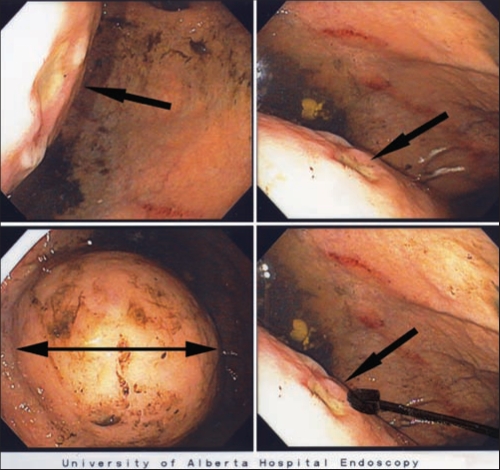

Once the patient was hemodynamically stable, an upper endoscopy was performed. No evidence of esophageal or gastric varices was found. In the mid-body of the stomach, a large 8 cm extrinsic mass over the posterior-inferior surface of the stomach was identified (Figure 1). Over the surface of the mass was a 5 mm ulcer with a flat nonbleeding red spot at its base (Figure 1). Given the patient’s history of aortic aneurysm repair with an endovascular graft (site unknown), the extrinsic mass was considered to be associated with a graft aneurysm and the ulcer, an aortoenteric fistula, as the bleeding site. The remainder of the stomach was endoscopically normal. The duodenum was normal except for a nonbleeding 2 mm superficial erosion with a white base in the second part. No hemostatic injections or biopsies of the extrinsic mass or ulcer were performed to avoid complicating a possible aortic graft aneurysm and aortoenteric fistula.

Figure 1).

Gastric endoscopy showing a large intramural mass (double-headed black arrow) on the posterior-inferior wall of the stomach near the fundus. The three single-headed black arrows identify different views of the 5 mm shallow ulcer overlying the top of the intramural mass

On completion of the upper endoscopy, the working diagnosis was an aortogastric fistula in the presence of an aortic graft aneurysm. The differential diagnoses included an intramural gastric neoplasia, likely a gastric leiomyoma or gastric hematoma. To further investigate this mass, a computed tomography (CT) angiogram was performed

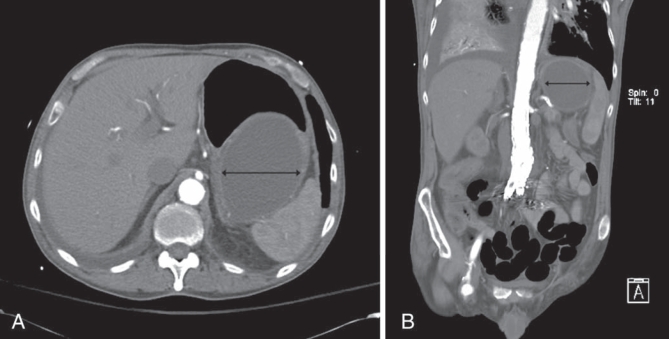

A CT angiogram demonstrated an aortobifemoral graft complicated by a proximal pseudoaneurysm, which had been repaired with an endovascular stent (Figure 2). This appearance had not changed when compared with a CT performed six months earlier. Specifically, there was no extravasation of contrast and no proximal extension of the aneurysm into the gastric region of the abdomen, confirming that the decrease in hemoglobin level was not secondary to an aortogastric fistula. No hepatic, splenic or pancreatic abnormalities were identified. However, there was a large, fluid-filled cystic mass coursing along the posterior aspect of the stomach, from the level of the fundus to the mid-body. The mass was homogeneous, intramural and measured 8 cm × 16 cm. At the caudal aspect of the cystic mass was a discrete, hypodense area consistent with active arterial contrast extravasation. This fluid-filled cystic mass was not communicating with the aorta and was a significant distance from the endovascular graft site (Figure 2B).

Figure 2).

Cross-sectional (A) and longitudinal (B) computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast images of the abdomen showing a well-defined homogeneous mass involving the inferior-posterior portion of the stomach (double-headed black arrow). Note that the mass is not communicating directly with the aorta and that it is significantly superior to the site of endovascular graft

These findings confirmed the diagnosis of an intramural gastric hematoma with a central bleeding ulceration, and correlated with the endoscopic appearance. It was hypothesized that the patient’s warfarin-associated anticoagulation therapy accelerated bleeding from a shallow benign gastric ulcer, with the arterial vessel bleeding into the intramural tissue plane as well as intraluminal. The patient was managed conservatively with reversal of the coagulopathy, and fluid and blood replacement. There was no further ulcer bleeding and the intramural gastric hematoma resolved on follow-up over the next eight weeks.

DISCUSSION

Although intramural hematomas of the gastrointestinal tract have been described, intramural gastric hematoma is extremely rare. A PubMed search for all reported adult cases of intramural gastric hematoma in the English literature was performed and identified 26 cases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Published literature on gastric intramural hematoma

| Cause | References | Cases, n (%) |

Management |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Surgical intervention | |||

| Coagulopathy | ||||

| Hemophilia | 5,6,14,17–19 | 6 (23.1) | 6 | 0 |

| Anticoagulation | 8,9,20,21 | 4 (15.4) | 3 | 1 |

| Others | 16,22–24 | 4 (15.4) | 0 | 4 |

| Aneurysm | 25–28 | 4 (15.4) | 1 | 3 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 12,13,29 | 3 (11.5) | 0 | 3 |

| Spontaneous | 2,24,30 | 3 (11.5) | 1 | 2 |

| Other causes | 7,27 | 2 (7.6) | 2 | – |

| Total | 26 | 13 | 13 | |

Diagnosis of gastric hematomas

In earlier case reports (5,9–13), upper gastrointestinal barium studies were used to investigate gastric hematomas. However, barium studies cannot readily distinguish a gastric hematoma from a solid tumour mass. Similarly, ultrasound has poor discriminatory capacity for gastric hematomas, showing an anechoic or hypoechoic pattern that is nonspecific and can mimic gastrointestinal neoplasm or inflammatory lesions (13,14).

The CT scan is the current diagnostic procedure of choice for gastrointestinal-wall hematomas because it has the ability to precisely differentiate whether a mass is solid or liquid. In 1982, Plojoux et al (15) reported the use of CT scanning to diagnose intramural hematoma of the small bowel. They described gastrointestinal hematomas as well-circumscribed, high-density homogeneous masses. Unlike gastrointestinal neoplasms, gastrointestinal hematomas lack signs of calcification and infiltration into other organs.

Angiography has also been used to diagnose gastric hematomas, although the primary reason for using this modality was therapeutic rather than diagnostic (8,16).

Management of gastric hematomas

Gastric hematomas secondary to intrinsic coagulopathy are generally managed conservatively. All six reported cases (5,6,14,17–19) of gastric hematomas secondary to hemophilia were managed through blood and coagulation factor replacement. Nevertheless, bleeding can be massive because one of the six documented patients died from ongoing hemorrhage (6).

There are only four reported cases of gastric hematomas associated with anticoagulation therapy (8,9,20,21). Only one of the four cases required therapeutic transcatheter arterial embolization (8). In that case, angiography revealed active extravasation of the contrast medium from the gastroparietal branch of the left gastric artery. The remaining three cases were managed conservatively with blood transfusions and reversal of the anticoagulation.

A surgical approach has also been used in the management of gastric hematomas. However, in both of the reported cases, amyloidosis with vascular microaneurysms, and persistent and repetitive bleeding was identified (22,23). One of the two patients died after surgery as a result of multiorgan failure secondary to hypovolemic shock (22) while the second patient had a favourable postoperative course (23).

The patient reported in the present case study was therapeutically anticoagulated with warfarin. Similar to previous reports, the diagnosis was confirmed with a CT scan and the patient was treated with conservative therapy. The patient recovered fully with no reccurrence during eight months of follow-up. Nevertheless, the patient experienced additional renal insufficiency secondary to hypovolemia, and CT contrast agent-induced nephropathy and required transient hemodialysis.

In this patient, it is likely that the small gastric ulcer was the initiating site for the gastric hematoma, with bleeding from the arterial vessel separating intramural gastric planes leading to intramural bleeding and the hematoma.

CONCLUSION

Gastric hematoma is a rare disorder. CT of the abdomen is the diagnostic modality of choice. Gastric hematomas secondary to coagulopathy can usually be managed with a conservative approach, and surgery should be reserved for hematomas secondary to structural abnormalities of either the gastric wall or gastric blood vessels.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes CE, III, Conn J, Jr, Sherman JO. Intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg. 1977;133:276–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui J, AhChong AK, Mak KL, Chiu KM, Yip AW. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of stomach. Dig Surg. 2000;17:524–7. doi: 10.1159/000051954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sollfrank M, Koch W, Waldner H, Rudisser K. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic biopsy. Rofo. 2001;173:157–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-10898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugai K, Kajiwara E, Mochizuki Y, et al. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic therapy for a bleeding duodenal ulcer in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Intern Med. 2005;44:954–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin PH, Chopra S. Spontaneous intramural gastric hematoma: A unique presentation for hemophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:430–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melato M, Falconieri G, Manconi R, Bucconi S. Intramural gastric hematoma and hemoperitoneum occurring in a patient affected by idiopathic myelofibrosis. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:301–2. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(80)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crema MD, Monnier-Cholley L, Maury E, Tubiana JM, Arrive L. What is your diagnosis? Extra-pleural hematoma. J Radiol. 2004;85(4 Pt 1):419–21. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(04)97603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imaizumi H, Mitsuhashi T, Hirata M, et al. A giant intramural gastric hematoma successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Intern Med. 2000;39:231–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balthazar EJ, Einhorn R. Intramural gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clinical and radiographic manifestations. Gastrointest Radiol. 1976;3:229–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02256371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott S, Bruce J. Submucosal gastric haematoma: A case report and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 1987;60:1132–5. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-60-719-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd TV, Johnson JC. Intramural gastric hematoma secondary to splenic rupture. South Med J. 1980;73:1675–6. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198012000-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothstein JD, Sandusky WR, Keats TE. Hematoma as a cause of radiographic deformity of stomach. Radiology. 1968;90:116–7. doi: 10.1148/90.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheward SE, Davis M, Amparo EG, Gogel HK. Intramural hemorrhage simulating gastric neoplasm. Gastrointest Radiol. 1988;13:102–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01889035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morimoto K, Hashimoto T, Choi S, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of intramural gastric and duodenal hematoma in hemophiliacs. J Clin Ultrasound. 1988;16:108–13. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870160208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plojoux O, Hauser H, Wettstein P. Computed tomography of intramural hematoma of the small intestine: A report of 3 cases. Radiology. 1982;144:24. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.3.6980432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kami M, Matsukura A, Kanda Y, Ogawa S, Makuuchi M, Hirai H. Intramural hematoma of stomach after splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 1999;84:669–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felson B. Intramural gastric lesion with sudden abdominal pain. JAMA. 1974;230:603–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.230.4.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin PH, Schnure FW, Chopra S, Brooks DC, Gilliam JI. Intramural gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(3 Pt 2):389–94. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright FW, Matthews JM. Hemophilic pseudotumor of the stomach. Radiology. 1971;98:547–9. doi: 10.1148/98.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durward QJ, Cohen MM, Naiman SC. Intramural hematoma of the gastric cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;71:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leborgne L, Mathiron A, Jarry G. Spontaneous intramural gastric haematoma as a complication of oral anticoagulant therapy mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1804. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iijima-Dohi N, Shinji A, Shimizu T, et al. Recurrent gastric hemorrhaging with large submucosal hematomas in a patient with primary AL systemic amyloidosis: Endoscopic and histopathological findings. Intern Med. 2004;43:468–72. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muraki M, Kanno Y, Higuchi K, et al. Laceration of gastric mucosa associated with dialysis-related amyloidosis. Clin Nephrol. 2005;64:448–51. doi: 10.5414/cnp64448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa BP, Manso C, Baldaia C, Alves FC, Sousa FC. Gastric pseudotumor. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:151–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langlois NE, Miller ID. Intramural gastric hematoma originating from an atherosclerotic aneurysm of a gastric artery. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:613–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuo S, Yamaguchi S, Miyamoto S, et al. Ruptured aneurysm of the visceral artery: Report of two cases. Surg Today. 2001;31:660–4. doi: 10.1007/s005950170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molnar P, Miko T. Multiple arterial caliber persistence resulting in hematomas and fatal rupture of the gastric wall. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:83–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiyama S, Zhu BL, Quan L, Tsuda K, Kamikodai Y, Maeda H. Unexpected sudden death due to a spontaneous rupture of a gastric dissecting aneurysm: An autopsy case suggesting the importance of the double-rupture phenomenon. J Clin Forensic Med. 2004;11:268–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng SC, Shariff M, Datta D, Hanna G, Holdstock G. Gastrointestinal: Gastric wall hematoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;2:915. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopal KV, Alvares JF. Spontaneous giant intramural hematoma of esophagus and stomach. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]