Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine the rate at which physicians report performing a digital rectal examination and comment on the prostate gland before performing colonoscopy in men 50 to 70 years of age.

METHODS:

A retrospective chart review of all men 50 to 70 years of age who had a colonoscopy in Kingston, Ontario, in 2005 was completed. It was noted whether each physician described performing a digital rectal examination before the colonoscopy, and if so, whether he or she commented on the prostate.

RESULTS:

In 2005, 846 eligible colonoscopies were performed by 17 physicians in Kingston, Ontario. In 29.2% of cases, the physician made no comment about having performed a digital rectal examination; in 55.8% of cases, the physician commented on having completed a digital rectal examination but said nothing about the prostate; and in 15.0% of cases, the physician made a comment regarding the prostate. No physician consistently commented on the prostate for all patients, and in no circumstances was direct referral to another physician or follow-up suggested.

DISCUSSION:

A colonoscopy presents an ideal opportunity for physicians to use a digital rectal examination to assess for prostate cancer. Physicians performing colonoscopies in men 50 to 70 years of age should pay special attention to the prostate while performing a digital rectal examination before colonoscopy. This novel concept may help maximize resources for cancer screening and could potentially increase the detection rate of clinically palpable prostate cancer.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Digital rectal examination, Prostate cancer, Screening

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer dans quelle proportion les médecins disent procéder à un toucher rectal et formuler des commentaires sur la prostate de leurs patients de sexe masculin âgés de 50 à 70 ans chez qu’ils s’apprêtent à effectuer une coloscopie.

MÉTHODE :

Les auteurs ont analysé rétrospectivement les dossiers de tous les hommes de 50 à 70 ans qui ont subi une coloscopie à Kingston, en Ontario, en 2005. Ils ont vérifié si les médecins avaient mentionné avoir fait un toucher rectal avant la coloscopie et, le cas échéant, s’ils avaient formulé des commentaires sur l’état de la glande.

RÉSULTATS :

En 2005, 846 coloscopies jugées admissibles aux fins de la présente étude ont été effectuées par 17 médecins de Kingston, en Ontario. Dans 29,2 % des cas, le médecin n’a pas fait mention d’un toucher rectal. Dans 55,8 % des cas, le médecin a signalé avoir fait un toucher rectal, mais sans fournir de renseignements sur l’état de la prostate et dans 15,0 % des cas, le médecin a commenté l’état de la prostate. Aucun des médecins n’a systématiquement commenté l’état de la prostate chez tous ses patients et aucun n’a mentionné avoir orienté un patient vers un collègue en vue d’une consultation directe ou d’un suivi.

DISCUSSION :

La coloscopie est l’occasion idéale d’effectuer un toucher rectal dans le but de dépister le cancer de la prostate. Les médecins qui effectuent des coloscopies chez des hommes de 50 à 70 ans devraient porter une attention spéciale à la prostate lorsqu’ils procèdent au toucher rectal avant la coloscopie. Cette nouvelle mesure permettrait une utilisation plus judicieuse des ressources en matière de dépistage du cancer et augmenterait potentiellement le taux de dépistage des cancers de la prostate palpables.

Prostate cancer remains the leading form of cancer diagnosed in Canadian men, accounting for roughly 27% of all cancers occuring in men and is responsible for the death of over 4000 men annually (1). More than 13% of Canadian men will develop prostate cancer in their lifetime and approximately 4% will die from the disease (1). The burden of prostate cancer on society is considerable; therefore, any measures to reduce mortality are worth considering, especially those that are cost effective, easy to implement and socially and professionally acceptable.

Although it may seem intuitive that screening for prostate cancer would have value to patients and the health care system, this matter is anything but straightforward. There are currently no clear and consistent guidelines as to if and how prostate cancer screening should be performed. However, the present consensus is that if screening is deemed appropriate for a given individual, both a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and a digital rectal examination (DRE) should be performed to best detect the presence of cancer (2–5). Many Canadian men older than 50 years of age are choosing to be screened for prostate cancer, and based on their age, life expectancy, personal beliefs about cancer screening and past experience with cancer, these same men are probably more likely to also choose screening for colorectal cancer. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in Canadians and is the second most common cancer-related cause of death in men (6). Similar to prostate cancer, approximately 90% of colorectal cancers diagnosed in 2006 were in individuals 50 years of age and older (6).

Colonoscopy is an important and frequently used screening tool in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. A colonoscopy is frequently preceded by a DRE to detect masses in the anal canal and lower rectum. This presents an opportunity to complete the more invasive portion of screening for prostate cancer, which has lower patient acceptance than the PSA blood test (7). However, it is unclear how many physicians are commenting on the prostate during the pre-endoscopy DRE, and whether those physicians who do comment on the prostate do so consistently with every patient they examine. Because there are no published guidelines that recommend that physicians performing colonoscopies pay particular attention to the prostate during the DRE, the present study was aimed at determining the proportion of physicians who do comment on the prostate while performing a pre-endoscopy DRE.

METHODS

The present retrospective chart review investigated all men 50 to 70 years of age who had a colonoscopy performed in Kingston, Ontario, in 2005. This age group was chosen based on the United States Preventive Task Force’s recommendations because these men represent the population for which prostate cancer screening is most relevant. Over 98% of all prostate cancers occur in men 50 years of age or older. Patients who, either based on age or significant medical problems, have a life expectancy of less than 10 years, are unlikely to benefit from screening based on the generally lengthy natural history of the disease (8).

Patients were identified by a review of the endoscopy database at the endoscopy unit of Hotel Dieu Hospital, Kingston, Ontario. All outpatient colonoscopies performed in Kingston are performed through this unit. Each colonoscopy performed was noted, regardless of whether it was the only procedure or one of several procedures a given patient had undergone in 2005. Procedures in which a DRE was clearly not indicated – for example, in which the scope was inserted into the patient’s colostomy – were excluded from the study. For each procedure, the patient’s demographics were recorded, along with the date, the physician, the indication(s) and the result(s). Most important, it was noted whether the physician described performing a DRE before the colonoscopy, and if so, whether he or she commented on the prostate. If the physician noted any concerns, it was recorded whether any remark was made regarding recommended follow-up or referral to another physician.

Before conducting the present study, ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used, including mean, median, SD and range, depending on the data distribution. For the statistical analysis, the SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc, USA) package was used.

RESULTS

In 2005, 846 eligible colonoscopies were performed in Kingston, Ontario. The mean (± SD) age of patients on the date of their procedure was 59.7±5.8 years (range 50 to 70 years). Seventeen different physicians performed the procedures, nine were gastroenterologists and eight were general surgeons; 58.2% of endoscopies were performed by gastroenterologists and 41.8% by general surgeons.

The three main reasons why patients had colonoscopies were for colorectal cancer screening, with or without a family history of the disease (32.0%); for a change in bowel habits such as rectal bleeding, diarrhea or abdominal pain (29.4%); and for colorectal cancer surveillance (25.1%). Together, these made up 86.5% of cases. In 37.8% of cases the bowel was found to be normal and in 42.0% of cases, polyps, either adenomatous or hyperplastic, were found. Colonic malignancy was detected in 3.1% of cases.

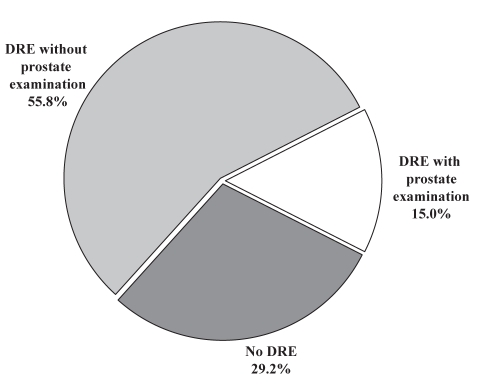

The physician did not report performing a DRE in 247 cases (29.2%), did report performing a DRE but said nothing about the prostate in 472 cases (55.8%), and made a comment regarding the prostate during a DRE in 127 cases (15.0%) (Figure 1). Of the 127 procedures in which a DRE (including a prostate examination) was reported, the physician noted that the prostate was normal or benign in 82 cases (64.6%) and the physician noted mild to moderate enlargement of the prostate, with or without induration, but without nodules in 37 cases (29.1%). The other cases in which a DRE with prostate examination was performed are described in Table 1. In no cases were direct referrals made or follow-up suggested.

Figure 1).

Percentage of cases in which the physician reported performing a digital rectal examination (DRE) before colonoscopy (70.8%) and in which the physician commented on the prostate while performing a DRE (15.0%)

TABLE 1.

Nature of comments made by physicians on the prostate during a digital rectal examination before colonoscopy (n=127)

| Comment | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Prostate was normal or benign | 82 (64.6) |

| Prostate was mildly or moderately enlarged, with or without induration, but without nodules | 37 (29.1) |

| Prostate could not be found because patient had previously had prostate cancer treated with a prostatectomy | 3 (2.4) |

| Prostate was nodular; however, patient said it was being followed by his family physician or urologist | 2 (1.6) |

| Prostate could not be observed due to the patient’s large size | 1 (0.8) |

| Prostate was significantly enlarged; clear documentation of this was made in the procedure note | 1 (0.8) |

| Prostate was enlarged and nodular; no reference to this being of concern | 1 (0.8) |

Of the 17 physicians who performed the colonoscopies, one did not report a DRE and two rarely reported a DRE; five physicians never commented on the prostate while performing a DRE and only two commented on the prostate in the majority of their cases (Table 2). The rates of comment on the prostate during DRE varied considerably among physicians from 0% to 59.3% of cases. On average, gastroenterologists reported a DRE before a colonoscopy more frequently than did general surgeons (78.6% of cases compared with 66.7% of cases, respectively); however, general surgeons were more than twice as likely as gastroenterologists to comment on the prostate while performing a DRE (32.2% of cases in which a DRE was performed compared with 14.0% of cases, respectively). Overall, general surgeons were approximately twice as likely as gastroenterologists to report both a DRE and comment on the prostate (21.5% of cases compared with 10.4% of cases, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Frequency at which physicians reported a digital rectal examination (DRE) before colonoscopy, and frequency at which a comment was made regarding the prostate during the DRE

| Physician performing colonoscopy | Procedures in which a DRE was reported, n (%) | Procedures performed in which a DRE was reported and in which a comment regarding the prostate was made, n (%) | Total procedures performed, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gastroenterologist | 65 (100.0) | 32 (49.2) | 65 |

| 2. Gastroenterologist | 40 (100.0) | 3 (7.5) | 40 |

| 3. Gastroenterologist | 63 (96.9) | 0 (0.0) | 65 |

| 4. General surgeon | 82 (96.5) | 47 (57.3) | 85 |

| 5. General surgeon | 27 (93.1) | 16 (59.3) | 29 |

| 6. General surgeon | 94 (93.1) | 8 (8.5) | 101 |

| 7. Gastroenterologist | 23 (92.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 |

| 8. Gastroenterologist | 75 (90.4) | 6 (8.0) | 83 |

| 9. General surgeon | 25 (86.2) | 3 (12.0) | 29 |

| 10. General surgeon | 6 (85.7) | 2 (33.3) | 7 |

| 11. Gastroenterologist | 13 (81.3) | 0 (0.0) | 16 |

| 12. Gastroenterologist | 37 (66.1) | 7 (18.9) | 56 |

| 13. Gastroenterologist | 24 (50.0) | 2 (8.3) | 48 |

| 14. General surgeon | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 |

| 15. Gastroenterologist | 23 (24.5) | 1 (4.3) | 94 |

| 16. General surgeon | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 99 |

| 17. General surgeon | 0 (0.0) | 0 (NA) | 1 |

| Total | 599 (70.8) | 127 (21.2) | 846 |

NA Not applicable

DISCUSSION

The primary outcome of the present retrospective chart review was that 70.8% of physicians who performed a colonoscopy reported a DRE before the procedure; however, only 15% commented on the prostate. No physician commented consistently on all patients, and general surgeons were more likely to report a DRE and comment on the prostate than gastroenterologists. Approximately one-third of physicians who reported a DRE and commented on the prostate noted that the gland was mildly to moderately enlarged, with or without induration, but none of these physicians made any note about recommended follow-up or referral.

Before making any recommendations based on our findings, one must consider the current thinking regarding prostate cancer screening. The extent of the benefit of screening for prostate cancer has not yet been established. The uncertainty hinges on the fact that screening for prostate cancer has not yet been directly linked to reduced mortality rates and increased quality of life, although certain trends point to the fact that it will. Most notably, over the past 15 years, reduced incidence rates for prostate cancer with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis and reduced prostate cancer mortality rates have been noted (9). Recently, a large-scale, 12-year study has shown a reduced risk of mortality associated with active treatment of low- to intermediate-risk prostate cancer in men 65 to 80 years of age compared with observation alone (10). It appears that this debate will continue for some time as we anticipate the results of two large randomized clinical trials (11,12) that are currently testing prostate cancer screening in an attempt to obtain definitive evidence that screening reduces prostate cancer mortality rates.

The role of the DRE in prostate cancer screening is also a contentious issue. Although PSA testing has been shown to be a more sensitive and specific screening method for prostate cancer (a sensitivity of 72.1% and specificity of 93.2% [using a minimum PSA of 4.0 ng/mL] compared with a sensitivity of 53.2% and specificity of 83.6% with the DRE), the DRE has been shown to detect cancer in some men with PSA levels below 4.0 ng/mL (13,14). Furthermore, dual modality screening has been shown to detect 83.4% of cancers in an early, localized state (13). The effectiveness of the DRE is also believed to be skill-related in that urologists seem to have better accuracy than other physicians. Moreover, when a patient has repeat examinations, the DRE has been shown to be more sensitive (15). These latter points suggest that there is potential to increase the sensitivity and specificity of the DRE. General surgeons and gastroenterologists perform high volumes of DREs, and thus, could be an ideal subset of physicians who can monitor abnormalities of the prostate. Patients with an abnormal DRE who are diagnosed with prostate cancer are defined as having higher local disease staging than those detected with PSA screening alone; and local disease staging is an independent predictor of disease recurrence (16). It is also known that elevation of PSA levels precedes clinically detectable disease by a number of years. Consequently, those patients with clinically palpable disease are at higher risk of suffering morbidity from prostate cancer and therefore more likely deserve case detection efforts (17).

Despite reservations, many Canadian men are choosing to be screened for prostate cancer, and because of their shared demographics, there is likely much overlap between these men and those requesting screening for colorectal cancer. It therefore appears logical to investigate ways to combine the screening for these two malignancies. Furthermore, some studies (18) have even shown an increased incidence of prostate malignancies in patients with colorectal cancer, and vice versa. It is believed that the biological association between colorectal cancer and prostate cancer may be based on shared genetic or environmental risk factors, or a combination of the two. Genetic and epidemiological studies (ie, of families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and of children of men diagnosed with prostate cancer before 70 years of age) point to a genetic basis. Environmental factors, such as a high fat diet, a high body mass index and alcohol consumption, have also been linked to an increased risk for developing both malignancies (18).

CONCLUSION

Although the present study demonstrated that not all physicians reported a DRE before colonoscopy, the majority did. Therefore, it seems reasonable to train physicians to pay more attention to the prostate during DREs and to ensure comments are made on any irregularities noted. Endoscopy-coupled screening for prostate cancer with DREs could complement a PSA test performed by a patient’s family physician on another occasion. Interestingly, it has been observed that in certain patients, colonoscopy can increase serum levels of PSA as well as the PSA ratio, most significantly within the first 24 h after the procedure, but even within the week that follows (19). Therefore, to avoid falsely elevated PSA levels and PSA ratio, it is advisable to perform PSA testing before a colonoscopy or some time after the procedure, especially in those patients with a history of borderline PSA levels. Based on the results of the present study, it is recommended that physicians performing a colonoscopy in men 50 to 70 years of age, pay special attention to the prostate while performing a DRE before the endoscopy.

Acknowledgments

Student research grant awarded to Tess Hammett by the Mach-Gaensslen Foundation of Canada. Thank you to the Mach-Gaensslen Foundation of Canada for providing funding for this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society/National Cancer Institute of Canada Canadian Cancer Statistics 2007. <http://129.33.170.32/ccs/internet/standard/0,3182,3172_14279_langId-en,00.html> (Version current at April 26, 2007).

- 2.Alberta CPG Working Group on Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines for the use of PSA and the early diagnosis of prostate cancer 2006. <http://www.topalbertadoctors.org/NR/rdonlyres/C0401885-CF7A-4ECB-B32D-0C9CE7D421AC/0/prostate_guideline.pdf> (Version current at April 26, 2007).

- 3.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:11–25. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Canadian Cancer Society Early detection for prostate cancer<http://www.cancer.ca/ccs/internet/standard/0,3182,3172_10175_74550606_langId-en,00.html> (Version current at June 25, 2007).

- 5.The BC Cancer Agency Positions of other medical organizations on screening for prostate cancer with PSA<http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPICancerManagementGuidelines/Genitourinary/Prostate/PSAScreening/PositionsofOtherMedicalOrganizationsonScreeningforProstateCancerwithPSA.htm> (Version current at June 25,2007).

- 6.Canadian Cancer Society/National Cancer Institute of Canada Canadian Cancer Statistics 2006. <http://www.cancer.ca/ccs/internet/standard/0,3182,3172_876141963_1260990479_langId-en,00.html> (Version current at June 25, 2007).

- 7.Nagler HM, Gerber EW, Homel P, et al. Digital rectal examination is barrier to population-based prostate cancer screening. Urology. 2005;65:1137–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for prostate cancer: Recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:915–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarone RE, Chu KC, Brawley OW. Implications of stage-specific survival rates in assessing recent declines in prostate cancer mortality rates. Epidemiology. 2000;11:167–70. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong YN, Mitra N, Hudes G, et al. Survival associated with treatment vs observation of localized prostate cancer in elderly men. JAMA. 2006;296:2683–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andriole GL, Reding D, Hayes RB, Prorok PC, Gohagan JK, PLCO Steering, Committee The prostate, lung, colon, and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial: Status and promise. Urol Oncol. 2004;22:358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroder FH. Detection of prostate cancer: The impact of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) Can J Urol. 2005;1(Suppl):2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-analysis of prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal examination as screening tests for prostate carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:95–101. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder FH, van der Maas P, Beemsterboer P. Evaluation of the digital rectal examination as a screening test for prostate cancer. Rotterdam section of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1817–23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.23.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feightner JW.Screening for prostate cancer Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care Ottawa: Health Canada; 1994812–23.<http://www.ctfphc.org/> (Version current at June 25, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potters L, Klein EA, Kattan MW. Monotherapy for stage T1-T2 prostate cancer: Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or permanent seed implantation. Radiother Oncol. 2004;71:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tornblom M, Eriksson H, Franzen S. Lead time associated with screening for prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:122–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozden N, Saruc M, Smith LM, Sanjeevi A, Roy HK. Increased cumulative incidence of prostate malignancies in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;34:49–54. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:34:1:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbatzas C, Dellis A, Grivas I, Trakas N, Ekonomou A, Kostakopoulos A. Colonoscopy effects on serum prostate specific antigen levels. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004;36:203–6. doi: 10.1023/b:urol.0000034674.19318.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]