Abstract

We examined the effects of teaching overt precurrent behaviors on the current operant of solving multiplication and division word problems. Two students were taught four precurrent behaviors (identification of label, operation, larger numbers, and smaller numbers) in a different order, in the context of a multiple baseline design. After meeting criterion on three of the four precurrent skills, the students demonstrated the current operant of correct problem solutions. These skills generalized to novel problems. Correct current operant responses (solutions that matched answers revealed by coloring over the space with a special marker) maintained the precurrent behaviors in the absence of any other programmed reinforcement.

Keywords: mathematics, precurrent behaviors, problem solving, word problems

The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (1989, 2000, 2005) has for many years recommended an increased focus on problem-solving tasks, typically taught through the use of word problems. The National Center for Educational Statistics reported, however, that only 36% of fourth graders in the United States were performing at or above the proficient level in identifying and appropriately using information to solve word problems (Perie, Grigg, & Dion, 2005). Students with developmental disabilities (e.g., autism) lag even further behind (Cawley, Parmar, Foley, Salmon, & Roy, 2001; Parmar, Cawley, & Frazita, 1996). The difficulties with word problem solving demonstrated by students across ability and age levels (National Assessment of Educational Progress, 1992) indicate a need for methods of instruction that can enhance performance of all students, particularly given the emphasis on educating students with disabilities in inclusive classrooms (Owen & Fuchs, 2002). Nevertheless, relatively little research has been reported on procedures for teaching word-problem solving compared to teaching basic foundation and computation skills, and most of the research has targeted students with learning disabilities (see Xin & Jitendra, 1999).

From an operant perspective, the behaviors necessary to solve mathematics word problems can be classified as precurrents. Precurrent behaviors are those that increase the effectiveness of a subsequent (current) behavior in obtaining a reinforcer (Polson & Parsons, 1994; Skinner, 1968). Once established, precurrent behaviors can be reinforced and maintained by the correct performance of the current behavior (Parsons, 1976; Skinner). For example, the current behavior of getting to a particular destination can reinforce and maintain the precurrent behavior of reading a map. Neef, Nelles, Iwata, and Page (2003) taught four precurrent behaviors for addition and subtraction word problems (identifying the initial value, change value, operation, and resulting value) in a sequential manner to 2 young adults with developmental disabilities. Once the precurrent behaviors were established, the number of correct problem solutions increased. These behaviors generalized to untaught problems.

The current investigation replicated the Neef et al. (2003) study and extended the research on instruction in mathematical problem solving in several ways. First, we systematically replicated the procedures used by Neef et al. with younger (elementary aged) students, 1 with autism and 1 without disabilities. Very few, if any, studies on teaching mathematical problem solving have targeted students with autism, who often have intact computational skills but difficulty in discriminating the type of operation or approach to use to solve word problems (Minshew, Goldstein, Taylor, & Siegel, 1994; Siegel, Goldstein, & Minshew, 1996). Second, we assessed the relation between precurrent and current behaviors with word problems that involved multiplication and division operations. Almost all of the investigations of instruction on word-problem solving with students with disabilities have targeted addition and subtraction problems. Third, we implemented a self-checking procedure to reduce the instructional demands on the teacher and to determine the extent to which a matching answer (i.e., the current operant of correct problem solution) was sufficient to maintain precurrent behaviors in the absence of other sources of reinforcement. Finally, we assessed generalization to novel word problems in the absence of spaces as stimulus prompts for the parts of the equation.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Matt was a 10-year-old boy with a diagnosis of autism who was enrolled in an inclusive fourth-grade classroom. Maddix was a 10-year-old typically developing girl who was enrolled in a regular education summer school program. During a preexperimental skills assessment, both participants (a) calculated correct answers for at least 80% of multiplication problems from 1 × 10 to 10 × 10, (b) calculated correct answers for at least 80% of division problems with a maximum dividend of 100, and (c) discriminated larger and smaller numbers from among at least 80% of pairs between 1 and 100. Nevertheless, both participants demonstrated difficulty in solving word problems and were nominated by their parents and a classroom teacher for participation in the study. Teaching sessions were conducted individually by another teacher (first author) at a table in the back of the participants' classrooms.

Stimulus Materials

A bank of 300 multiplication and division word problems was created using the equations A × B = C and A ÷ B = C derived from a review of third- and fourth-grade mathematics curricula (e.g., “Nathan's wall is 12 feet wide. How many posters can he hang on his wall if each poster is 2 feet wide?”). Variations were created by substituting proper names, nouns, verbs, and numbers. Multiplication problems had products of 100 or less, and division problems had quotients of 10 or less without remainders. Each worksheet had 10 problems drawn randomly from the bank. Each problem was used only once during the study. Correct numbers for the word-problem equations on the training worksheets were written below the corresponding spaces with a color-changing marker and were invisible until colored over with a developing marker.

Experimental Design

A multiple baseline design across behaviors was used to examine the effects of teaching four precurrent behaviors (identification of label, operation, larger number, and smaller number) on the current behavior (correct solution) of word problems. Precurrent behaviors were trained in a different order for the 2 participants. Continued baseline measurement of the current operant permitted assessment of the effects of sequential acquisition of each precurrent behavior on the current operant.

Teaching Procedure

Typically, one to two 10- to 15-min teaching sessions were conducted 5 days per week throughout the intervention. Teaching included up to four phases, each corresponding to instruction in a precurrent behavior that had not yet been acquired. Instruction in each of the four phases (identification of label, operation, larger number, and smaller number, respectively) occurred as needed and followed the same procedure (described below). For each precurrent behavior, participants were taught to write the response in the corresponding space of an equation below the word problem. Prompts for each precurrent behavior, along with definitions of correct and incorrect responses, are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prompts and Correct and Incorrect Responses for Prompted Teaching Trials

At the beginning of each phase, the teacher demonstrated the target precurrent behavior on a worksheet with five practice problems. Practice worksheets contained a word problem and an equation with all elements filled in except for the target precurrent behavior and the current behavior. The solution was prewritten in invisible ink. The teacher read the problem aloud and delivered the corresponding verbal prompt (Table 1). She then identified and modeled the correct response. This consisted of underlining and stating either the specific words in the problem that indicated the solution's label (identification of label), the operation (identification of operation), or the number (identification of larger number and smaller number) depending on the specific precurrent behavior being taught. Next, the teacher wrote the correct response in its corresponding space. She then solved the resulting number sentence and entered the current operant on the final answer space. Finally, the teacher modeled a self-checking procedure by coloring under the answer space with a developing marker that revealed the current operant (solution), and read the resulting number sentence aloud.

Following modeling, the teacher presented the participant with a worksheet that contained 10 different word problems and corresponding equations with blank spaces for the precurrent being taught, any previously taught precurrents, and the current operant (i.e., the solution). The participant was instructed to complete the equation with a written response in the corresponding spaces for (a) the precurrent behavior being taught, (b) all previously taught precurrent behaviors (e.g., identification of label, operation, larger number, or smaller number), and (c) the solution, and to then check the solution using the developing marker. Teaching trials began with guided instruction during which the teacher presented the prompt (Table 1) for the precurrent behavior being trained. Previously taught precurrent behaviors were not prompted. After completion of the self-check procedure, the teacher prompted correction of any inaccurate responses, if necessary, by underlining the appropriate part of the word problem.

When the participant achieved criterion of at least 90% correct for the target precurrent behavior, the subsequent session used unprompted trials. The participant was given the worksheet to complete and check independently. When the participant met a criterion of at least 90% correct for two consecutive sessions with unprompted trials on the target precurrent behavior, a probe was conducted (described below). Teaching was then initiated on another precurrent behavior (unless probe data indicated an increasing trend, in which case probes continued until performance was stable). If the participant did not meet criterion during a session with unprompted trials, the teacher returned to guided instruction with prompted trials until the participant again met criterion.

Probes

Probes were conducted before training (baseline), each time the student met training criterion on a target precurrent behavior (intervention), and after all precurrent behaviors had been taught (generalization). During each 20-min probe session, the teacher gave the participant a worksheet that contained 10 word problems. Completion of each word problem consisted of writing the object of the word problem (label), the correct operation (multiplication or division) that would lead to the solution, the larger number referenced in the problem, the smaller number referenced in the problem, and the solution to the equation. During baseline and intervention probes, participants wrote their answers below the word problem on lines and boxes that corresponded to each of the four precurrent behaviors and the current behavior. No consequences were delivered for correct or incorrect responses. After all precurrent behaviors had met mastery criterion, a generalization probe was conducted in the same manner, except that the worksheets did not contain lines for numbers and labels or a box for the operation.

Data Collection

Data were collected on the written responses during teaching trials and probes. Correct responses were defined, respectively, as having the correct numbers in the appropriate order for larger number and smaller number, the correct operation symbol separating the larger and smaller numbers, and the correctly labeled solution following the equal sign. Labels were counted as correct if they corresponded with the noun represented in the math problem. Any other response (or no response) was scored as incorrect.

Interobserver Agreement

Two graduate students in special education independently scored student responses on 31% of the training and probe sessions across all conditions for each participant. Point-by-point interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements on each component of a problem by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Mean agreement scores were 98.7% or above (range, 80% to 100%) for both training and probe sessions for each participant.

Procedural Integrity

Procedural integrity was assessed on 36% of all training and probe sessions by three graduate students in special education who had been trained to a criterion of at least 90% agreement in scoring a sample videotaped session using a procedural checklist of the behaviors outlined in the experimental methods. Procedural integrity was calculated by dividing the total number of steps performed by the teacher by the total number of steps and multiplying by 100%. The mean score was 99.3% (range, 93% to 100%).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

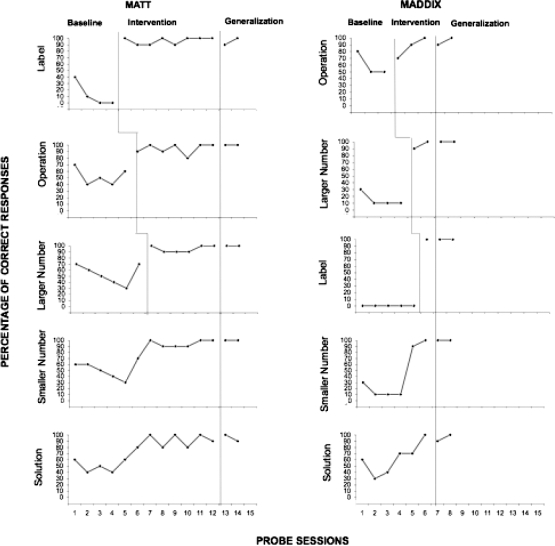

Figure 1 shows the percentage of correct precurrent and current responses during baseline, intervention, and generalization probes (data for teaching sessions are available from the second author). For both participants, correct responses for label, operation, and larger number increased following training. Matt's mean percentages of correct precurrent responses during baseline and intervention, respectively, were 13% and 96% for label, 52% and 96% for operation, and 53% and 96% for larger number. Maddix's mean percentages of correct precurrent responses during baseline and intervention, respectively, were 60% and 90% for operation, 15% and 98% for larger number, and 0% and 100% for label. Despite her low baseline for larger and smaller numbers, she often obtained a correct solution for multiplication problems that, unlike division problems, could be derived irrespective of the order of the two sets of numbers in the equation. For both participants, correct responding for the smaller number emerged following training on the larger number and therefore was not trained. Following training on the first three precurrents, correct solutions increased. Both participants maintained high percentages of correct responses on generalization probes (range, 90% to 100%).

Figure 1.

The percentage of correct responses during mathematics probes across baseline, intervention, and generalization conditions for Matt (left) and Maddix (right).

The results replicate the findings of Neef et al. (2003) in that systematic instruction on precurrent behaviors that represented the component parts of a problem was an effective method for establishing generative skills in the solution of arithmetic word problems. These results extend the generality of Neef et al. by demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach with a wider range of students (a student with autism and a typically developing student) and with word problems that involved other types of operations (multiplication and division), which rarely have been targeted in research on problem solving. Given the move toward inclusion, there is a need for procedures that are effective in addressing the goals of mathematics instruction across a spectrum of learners.

In addition to being effective, instruction should be efficient. The procedures used in the current study were efficient in several respects. First, instruction was limited to the identification of the basic elements and operations involved in a problem without the use of cognitive strategies that prompt self-reflection (e.g., “What did you notice about how you did your work?”; Naglieri & Gottling, 1995) that have characterized other approaches. Second, by teaching precurrent behaviors sequentially and probing performance as each was mastered, instruction was limited to those behaviors that did not emerge as a result of training previous precurrents. Thus, once identification and placement of the larger number in the equation was mastered, students were able to discriminate the smaller number, obviating the need for training on that step, or on the solution. The self-checking procedure (coloring over the space with a disclosing marker to reveal the answers) enabled students to receive immediate feedback and reinforcement for correct responses while they worked independently, thereby further reducing demands on teacher time. Finally, instruction resulted in generative problem solving (i.e., responding to novel stimuli in a way that enabled solution of multiple types of multiplication and division word problems). Efficiency might be further enhanced by teaching the strategies in the context of group instruction.

Problem solving involves an interresponse relation in which the occurrence of precurrent behaviors makes the solution (current operant) more likely (Skinner, 1953, 1966, 1968, 1969); the solution, in turn, may reinforce the precurrent behaviors. Parsons (1976) and Parsons, Taylor, and Joyce (1981) showed that precurrent collateral behavior was maintained when reinforcement was made contingent on a subsequent current operant, and that the current operant decreased when collateral precurrent behaviors were prohibited. In the present study, it was not possible (or desirable) to reverse or prevent the precurrent behaviors once they were acquired. However, precurrents maintained at a high level of accuracy in the absence of any programmed reinforcement other than producing the correct response (revealed by coloring over the space with a developing marker). This lends support to the findings of Parsons and colleagues in demonstrating the relation between precurrent and current behaviors. The current study suggests an approach that might be applied in future research to teaching more complex discriminations (e.g., word problems that contain irrelevant information) or advanced mathematical skills (e.g., multistep problems or those with remainders) to many students.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a master's thesis conducted by the first author. We thank Ron DeMuesy, Amanda Guld, and Kathleen Heron for their assistance with assessments of interobserver agreement and procedural integrity.

REFERENCES

- Cawley J, Parmar R, Foley T.E, Salmon S, Roy S. Arithmetic performance of students: Implications for standards and programming. Exceptional Children. 2001;19:124–142. [Google Scholar]

- Minshew N.J, Goldstein G, Taylor H.G, Siegel D.J. Academic achievement in high-functioning autistic individuals. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1994;16:261–270. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglieri J.A, Gottling S.H. A study of planning and mathematics instruction for students with learning disabilities. Psychological Reports. 1995;76:1343–1354. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.76.3c.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Assessment of Educational Progress. NAEP 1992 mathematics report card for the nation and the states (Report No. 23-ST02) Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Curriculum and evaluation of standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Curriculum and evaluation of standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston, VA: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neef N.A, Nelles D, Iwata B.A, Page T.J. Analysis of precurrent skills in solving mathematics story problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:21–33. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R.L, Fuchs L.S. Mathematical problem-solving strategy instruction for third-grade students with learning disabilities. Remedial and Special Education. 2002;23:268–278. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar R, Cawley J, Frazita R. Word problem solving by students with and without mild disabilities. Exceptional Children. 1996;62:415–429. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J.A. Conditioning precurrent (problem solving) behavior of children. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis. 1976;2:190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J.A, Taylor D.C, Joyce T.M. Precurrent self-prompting operants in children: “Remembering.”. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1981;36:253–266. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1981.36-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perie M, Grigg W, Dion G. The nation's report card: Mathematics 2005 (NCES 2006–453) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Polson D.A.D, Parsons J.A. Precurrent contingencies: Behavior reinforced by altering reinforcement probability for other behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1994;61:427–439. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D.J, Goldstein G, Minshew N.J. Designing instruction for the high-functioning autistic individual. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 1996;8:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Science and human behavior. New York: Free Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. An operant analysis of problem solving. In: Kleinmuntz B, editor. Problem solving: Research, method, and inquiry. New York: Wiley; 1966. pp. 225–257. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. The technology of teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Xin Y.P, Jitendra A.K. The effects of instruction in solving mathematical word problems for students with learning problems: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Special Education. 1999;32:207–225. [Google Scholar]