Abstract

Background

The prostatitis syndrome is a multifactorial condition of largely unknown etiology. The new NIH classification divides the prostatitis syndrome into a number of subtypes: acute bacterial prostatitis, chronic bacterial prostatitis, inflammatory and noninflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and asymptomatic prostatitis.

Methods

This article is based on a selective review of the literature regarding the assessment and management of the prostatitis syndrome and on a recently published consensus statement of the International Prostatitis Collaboration Network.

Results

Pathogenic organisms can be cultured only in acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis. These conditions should be treated with antibiotics, usually fluoroquinolones, for an adequate period of time. 90% of patients with prostatitis syndrome, however, suffer not from bacterial prostatitis but from chronic (abacterial) prostatitis / chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). It remains unclear whether CP/CPPS is of infectious origin, and therefore the utility of a trial of antimicrobial treatment is debatable. Treatment with alpha receptor blockers is recommended if functional subvesical obstruction is documented or suspected. Symptomatic therapy for pelvic pain should be given as well.

Conclusions

The prostatitis syndrome is a complex condition with a tendency toward chronification. It is important, therefore, that the patient be fully informed about the diagnostic uncertainties and the possibility that treatment may meet with less than complete success.

Keywords: prostatitis, chronic disease, NIH classification, fluorquinolones, alpha blockers

About 10% of all men suffer from the symptoms of prostatitis syndrome (1). However, the frequency of bacterial prostatitis is only 7% (2). It may be assumed that all other symptomatic patients suffer from inflammatory or noninflammatory pelvic pain syndrome and the prostate is not involved in all cases. Asymptomatic prostatitis is almost always histologically detected in prostatic resection or biopsy specimens from patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (3) or prostatic carcinoma (4). The frequency of prostatitis in infertility is still unclear.

The objective of the current review article is to describe practical management of the complex syndrome of prostatitis. For this purpose, the authors have performed a selective review of the literature in "Medline" and "Pubmed," together with a recently published consensus report from the International Prostatitis Collaboration Network on this theme (1).

Definitions

In accordance with the classification of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), prostatitis syndrome is classified into four categories (5).

Acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP), category I

ABP is characterized by severe obstructive and irritative symptoms of the lower respiratory tract, pain in the area of the prostate, and acute bacterial urinary tract infection (UTI), with systemic involvement.

Chronic bacterial prostatatis (CBP), category II

CBP is caused by chronic bacterial infection of the prostate, with or without prostatic symptoms. The same bacterial pathogen is often found with recurrent urinary tract infection.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)

CP/CPPS is split into inflammatory CP/CPPS (category IIIa) and noninflammatory CP/CPPS (IIIb). CP/CPPS is characterized by chronic pelvic pain and often by difficulties in micturition, without detection of an infection of the urinary tract.

Asymptomatic prostatitis, category IV

In asymptomatic prostatitis, inflammation of the prostate is detectable, although the patient does not report any symptoms or difficulties in this area.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Acute bacterial prostatitis

ABP is a severe systemic infection. It may arise spontaneously (90% of cases) or after manipulations on the urogenital tract (6). Pathogens include Escherichia coli, other enterobacteria, enterococci, and occasionally Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Complications from ABP include acute urinary retention, epididymitis, prostatic abscess, urosepsis, and CBP. Development of urosepsis or CBP can be prevented by timely and effective therapy. A prostatic abscess develops in about 3% of all cases; ABP after manipulations significantly more often leads to an abscess than does spontaneous ABP (6).

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

5% to 10% of patients with the diagnosis of prostatitis syndrome are suffering from CBP (1). This is often triggered by an infection of the urinary tract. The pathogen spectrum includes that of complex urinary tract infections, with gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, although the latter often occur only transiently. Animal experiments have shown that chronic infection leads to the formation of a biofilm in the prostatic acini. This means that the pathogens form colonies there with special growth conditions (7).

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

The etiology of CP/CPPS is often unclear. Five different causes have been discussed—infection, detrusor-sphincter dysfunction, immunological dysfunction, interstitial cystitis, and neuropathic pain (1):

Prokaryotic DNA sequences are found in some patients with CP/CPPS IIIa and this may indicate that there are pathogenic micro-organisms in the prostate which cannot be cultured (1).

It has frequently been reported that patients with CP/CPPS suffer functional obstruction during bladder emptying. Inadequate relaxation of the bladder neck during micturition leads to turbulent infravesicular urinary flow, with urinary reflux into the prostatic canaliculi. This results in chemically triggered inflammation of the prostate with release of mediators. The effects of these include stimulation of the pain nerve fibers (1).

Other studies have shown that patients with CP/CPPS exhibit raised levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and lowered levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as evidence of autoimmune processes (1).

An American group has found a positive intravesicular potassium sensitivity test in patients with CP/CPPS. This may indicate interstitial cystitis. The authors concluded that CP/CPPS and interstitial cystitis share the feature of uroepithelial dysfunction (1). These findings have not yet been confirmed.

There is experimental evidence for an axis between sensory nerves and mast cells as a pain mechanism. In an animal model of prostatitis, it has been shown that neural structures lie extremely close to prostate glands. Spinal neurons are stimulated through mast cell–induced PAR-2 (protease-activated receptor-2) activation and this may produce pain.

Asymptomatic prostatitis

Chronic inflammation can lead to the release of reactive oxygen species and these not only have deleterious effects on sperm parameters, but also induce other damage to cell walls and DNA in prostate epithelial cells and could even contribute to prostatic neoplasias in this way (4). Serum PSA (prostate-specific antigen) may be raised and then return to normal values once the inflammation decreases (8).

Diagnosis

The recommended evaluation of prostatitis syndrome is illustrated in box 1 and in figures 1, 2, and 3 (1).

Box 1. Evaluation of prostatitis syndrome (1).

-

Acute bacterial prostatitis (NIH category I)

Men with symptoms of ABP should be given urine analysis, with urine culture and sensitivity testing.

Initial imaging is normally not recommended; if a prostate abscess is suspected, transrectal sonography should be performed.

-

Chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH category II)

4-glass or 2-glass test to detect leukocytes, with bacterial culture and sensitivity testing

Ejaculate culture is of poor sensitivity and should not be performed as primary diagnostic measure.

Prostate imaging should only be performed in special cases, for example, if the condition is resistant to treatment.

The CPSI questionnaire should be used to evaluate the symptoms, but should not be used for diagnosis in isolation.

-

Chronic prostatitis / chronic pelvic pain syndrome (NIH category III)

-

Recommended investigations

4-glass or 2-glass test to detect leukocytes, with bacterial culture and sensitivity testing

The CPSI questionnaire should be used to evaluate the symptoms, but should not be used for diagnosis in isolation.

Digital rectal investigation of the prostate and other pelvic structures

Psychological (psychosomatic) evaluation for specific patients—for example, if depressive disorder suspected

-

Optional investigations

Urinary flow rate, determination of residual urine, and other urodynamic studies

Examination of ejaculate for leukocytes using special methods, such as peroxidase staining, leukocyte elastase

-

Investigations not routinely recommended

Serum PSA

Modified potassium chloride test

Prostate imaging

Detection of C. trachomatis and mycoplasmas

Cytoscopy

-

Investigations not conclusively recommended

Evaluation of prostate by histopathology and molecular microbiology

Immune cells and mediators

-

-

Asymptomatic prostatitis (NIH category IV)

No evaluation, unless antibiotic therapy is considered because of PSA increase or infertility

CPSI, Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index;

PSA, prostate-specific antigen

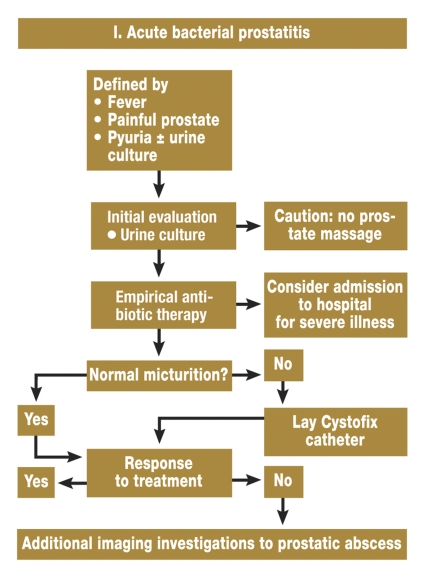

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the management of acute bacterial prostatitis

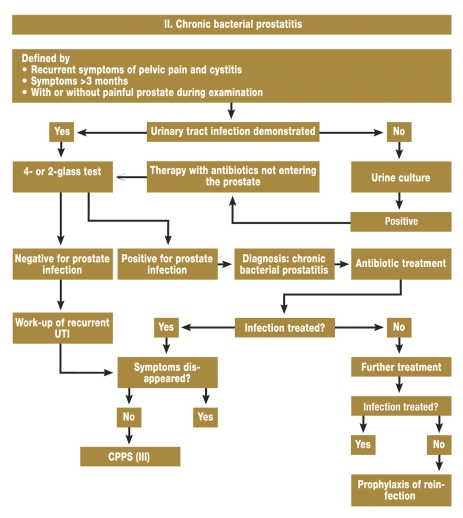

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the management of chronic bacterial prostatitis (1); UTI, urinary tract infection

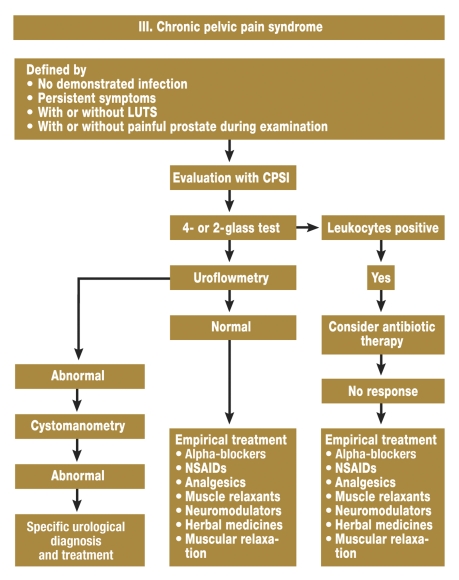

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the management of chronic pelvic pain syndrome (1); LUTS, symptoms of the lower urinary tract; CPSI, Chronic Prostatitis Symptoms Index; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

Acute bacterial prostatitis

Acute bacterial prostatitis (NIH category I) is an acute clinical picture, characterized by intense perianal pain, fever, and chills. There are dysuric and pollakisuric symptoms, which can peak in urinary retention. Prostatic abscesses are possible, as is urosepsis, the most severe complication (1). ABP is diagnosed microbiologically by detecting the pathogens in the midstream urine. Prostatic massage is contraindicated. Regularly increased PSA values are a serum marker; these regress after antibiotic therapy. Transrectal ultrasound of the prostate (TRUS) should be carried out to exclude prostatic abscess.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

The symptoms of CBP (NIH category II) cannot be distinguished from those of CP/CPPS (NIH category III). The symptom complex can be split into

pain,

irritative symptoms during micturition, and

sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction, loss of libido).

Recurrent infections of the urinary tract with the same pathogen are typical. The patient may be free of symptoms between the episodes (1).

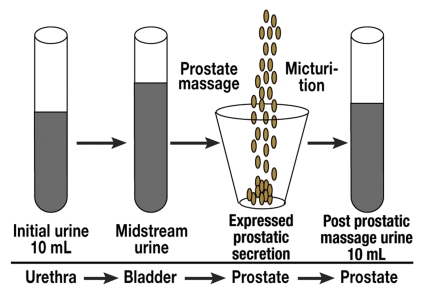

CBP is demonstrated either with a 4-glass test (initial urine, midstream urine, expressed prostatic secretion, urine after prostatic massage) (9) (figure 4) or with a 2-glass test (midstream urine and post prostatic massage urine) (1). The two diagnostic methods can be regarded as clinically equivalent. The bacterial count in the prostatic secretion and/or in the post prostatic massage urine should be 10-fold greater than in midstream urine. In addition, leukocytes or noncellular markers of inflammation (for example, leukocyte elastase or interleukin-8) must be detected in prostatic secretion and/or in post prostatic massage urine. A bacteriological investigation of ejaculate alone is not adequate, as the microbiological findings only agree with the results of the 2-glass or 4-glass tests in about half the cases (1). The test for leukocytes in ejaculate must be performed with special stains (for example, peroxidase stain), to distinguish leukocytes microscopically from the precursors of spermatozoa (table 1).

Figure 4.

Sketch of the 4-glass test for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome (9)

Table 1. Criteria for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis (1).

| 2- or 4-glass test | |

| Leukocytes (n) | ≥10/mm3 in post prostatic massage urine or |

| ≥10/1000 × expressed prostatic secretion | |

| Bacteria (CFU/mL) | Post prostatic massage urine / expressed prostatic secretion ≥10 × initial midstream urine |

| Ejaculate | |

| Leukocytes (n) | >106 PPL/mL |

| Bacteria | Not reliable |

PPL, peroxidase-positive leukocytes; CFU, colony forming units

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

In most patients, the dominant symptom is pain. This tends to be concentrated in the anorectal and genital areas, but may also affect the whole pelvic area (1). The symptoms should have been present for at least 3 months within the previous 6 months. The symptoms must be validated with the standard questionnaire of the National Institute of Health—Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) (10). This questionnaire has three sections—pain, micturition, and quality of life. Experience has shown that the section on pain provides the best discrimination between men with and without CP/CPPS. From a pain score of >10, it is generally assumed that the patient has manifest prostatitis symptoms (11). Changes in the overall score correlate with the therapeutic response (15). Depression and psychosocial symptoms are concentrated in patients with CP/CPPS and these must be addressed at the same time (11). Cooperation with a psychologist or a physician trained in psychosomatic medicine is helpful here. The 4-glass or 2-glass tests and the ejaculate test can be used to distinguish between the inflammatory and noninflammatory forms (12). The exact limits in the ejaculate for distinguishing between inflammatory and noninflammatory CP/CPPS are currently being discussed (table 2) (13, 14).

Table 2. Current thresholds of the Giessen prostatitis clinic for the diagnosis of CP/CPPS (CP/CPPS IIIa versus CP/CPPS IIIb) (12– 14, 24).

| CP/CPPS IIIa | CP/CPPS IIIb | ||

| Expressed prostatic secretion | ≥10–20/1000 × | <10–20/1000 × | |

| Post prostatic massage urine | ≥10/mm3 | <10/mm3 | |

| Ejaculate | PPL | ≥0.113 × 106 PPL/mL | <0.113 × 106 PPL/mL |

| Elastase | ≥280 ng/mL | <280 ng/ml | |

| IL-8 | 10 630–19 501 pg/mL | 2033–5287 pg/mL | |

PPL, peroxidase-positive leukocytes; elastase, leukocyte elastase; IL-8, interleukin 8.

If there is evidence for obstructive micturition symptoms, this must be investigated with uroflowmetry and residual urine, possibly with cystomanometry. Cystoscopy, computed tomography, and MRI of the prostate are not recommended (1). Possible differential diagnoses are diseases of the rectum, the external genitals, the urethra, and the bladder, as the nerves of other pelvic organs may interact with prostatic innervation (15).

Asymptomatic prostatitis

Asymptomatic prostatitis is diagnosed by chance, for example, during investigation of infertility or prostatic carcinoma. The histological diagnosis of prostatitis should employ the standardized classification of the International Prostatitis Network (16). Whether histologically manifest chronic prostatitis with inflammatory proliferative atrophy can develop into prostatic carcinoma is currently a matter of violent controversy (4, 17).

Treatment

The recommended treatment of prostatitis syndrome is shown in box 2 and in figures 1, 2, and 3 (1).

Box 2. Treatment of prostatitis syndrome (1).

-

Acute bacterial prostatitis (NIH category I)

Treatment in hospital, initially empirical parenteral therapy

Broad spectrum penicillin with beta-lactamase inhibitor; third generation cephalosporin, fluoroquinolone, aminoglycoside in combination with ampicillin for empirical therapy

If indicated, indwelling urinary catheter

Drainage if prostatic abscess

Further treatment with oral fluoroquinolones for 2 to 4 weeks

-

Chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH category II)

Oral fluoroquinolones for ceptible bacteria for 4 to 6 weeks

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria for 3 months

-

For treatment resistant patients:

Intermittent antibiotic treatment of acute symptomatic cystitis

Low dose antibiotic suppression therapy (for example, nitrofurantoin)

Radical TURP or simple prostatectomy (as last resort)

-

Chronic prostatitis / chronic pelvic pain syndrome (NIH category III)

-

Recommended therapies

Alpha-receptor blocker therapy for newly diagnosed patients not previously treated with alpha-blockers

Antimicrobial therapy for newly diagnosed patients not previously treated with antibiotics

Multimodal symptomatic therapy

-

Not recommended therapies

Alpha-receptor blockers for patients with prior multiple therapies

Anti-inflammatory monotherapy

Antimicrobial therapy for patients with prior multiple therapies

5-alpha-reductase inhibitor monotherapy

Minimally invasive therapies, such as TUNA, laser therapies, etc.

Invasive surgical therapies, such as TURP and radical prostatectomy

-

Therapies which cannot yet be conclusively evaluated

TUMT

Mepartricin

Quercetin and other herbal drugs

Biofeedback

Physical therapies (such as hyperthermia)

Acupuncture

Electromagnetic stimulation

Immunomodulatory substances

Muscle relaxants

Neuromodulatory substances

Modulation of the Nervus pudendus

-

Asymptomatic prostatitis (NIH category IV)

Antimicrobial therapy can be considered for specific patients with raised PSA or infertility.

TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate; TUNA, transurethral needle ablation of the prostate; TUMT, transurethral microwave thermotherapy of the prostate; PSA, prostate-specific antigen

Acute bacterial prostatitis

Antibiotic therapy is started empirically. Fluoroquinolones are the most effective antibiotics for sensitive bacteria. After resistance has been determined, specific oral antibiotic therapy should be performed for at least 2 to 4 weeks. The recurrence rate for ABP is about 13% (6). If there is residual urine, alpha-receptor blockers should be used. If there is urine retention, a single-use or indwelling suprapubic catheter should be laid. At least from 1 cm in size, a prostatic abscess should be treated by puncture and drainage. These recommendations are based on an international consensus (1).

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Fluoroquinolones penetrate relatively well into the prostate and are therefore the therapy of choice for CBP. They should be administered for 4 weeks. If the pathogen is resistant to fluoroquinolones, therapy with cotrimoxazole for 3 months is recommended (1).

For recurrent CBP, either each episode can be treated with antibiotics, or long-term antibiotic prophylaxis can be performed for at least 6 months. Surgical procedures such as transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and radical prostatectomy must be regarded as the last resort, or as therapy for concomitant obstruction (TURP) (1, 18). The results of selected studies are shown in table 3.

Table 3*1. Cumulative microbiological eradication rates in patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis and therapy with fluoroquinolones (1).

| Quinolone | Daily dose (mg) | Therapy duration (days) | Number of evaluable patients | Microbiological cure (%) | Duration of follow-up (months) | Author and year |

| Norfloxacin | 800 | 28 | 14 | 64 | 6 | Schaeffer AJ et al.; 1990 (e2) |

| Norfloxacin | 4–800 | 174 | 42 | 69 | 8 | Peppas T et al.; 1989 (e3) |

| Ofloxacin | 400 | 14 | 21 | 67 | 12 | Pust RA et al.; 1989 (e4) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 14 | 15 | 60 | 12 | Weidner W et al.; 1987 (e5) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 28 | 16 | 63 | 21–36 | Weidner W et al.; 1991 (e6) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 60–150 | 7 | 86 | 12 | Pfau A; 1991 (e7) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 28 | 34 | 76 | 6 | Naber KG et al.; 2000 (e8) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 28 | 78 | 72 | 6 | Naber KG et al.; 2002 (e9) |

| Lomefloxacin | 400 | 28 | 75 | 63 | 6 | Naber KG et al.; 2002 (e9) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 000 | 28 | 188 | 77 | 6 | Bundrick W et al.; 2003 (e10) |

| Levofloxacin | 500 | 28 | 189 | 75 | 6 | Bundrick W et al.; 2003 (e10) |

| Levofloxacin | 500 | 28 | 116 | 84 | 6 | Naber KG et al.; 2008 (e11) |

*1 This table is restricted to studies in which the diagnosis was made with an adequate localization test (such as the 4-glass test), with a follow-up of 6 months

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

As functional obstruction may cause this syndrome, therapy with alpha-receptor blockers is of great significance. Therapy for at least 6 months is recommended, as this leads to down-regulation of the alpha-receptors in the prostate (1). Muscle relaxants may be used if there is evidence for functional abnormalities in the pelvic floor muscle. Intraprostatic injection of botulinum toxin A is currently being investigated in these patients (19) and may offer a new therapeutic approach.

Another pathogenetic hypothesis is chronic infection with bacteria that are difficult to detect and cannot be cultured. For this reason, it is justified to treat CP/CPPS IIIa patients with fluoroquinolones if they have previously not been exposed to antibiotics—just as with CBP patients (1). If the symptoms do not improve within two weeks, antibiotic therapy should not be continued.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase, leading to a favorable effect on prostatic inflammation (20). For this reason, patients with dominant pain may be given NSAIDs. Some herbal medicines act in a similar manner and could possibly be used, although they have not yet been subjected to adequate clinical studies (1). Analgesics with other modes of action (e.g. central) are indicated for intense pain. Anticholinergic drugs may be used for symptomatic treatment of patients with dominant micturition problems, including urinary urgency linked to irritable bladder.

If a patient exhibits the symptoms of CP/CPPS, but without bacterial or inflammatory findings, the clinical picture is often classified as psychosomatic (21). The diagnosis of a somatoform disorder must be carefully considered in the context of other possible diagnoses, in close cooperation with a urologist. In such cases, it is particularly important to define accompanying depressive symptoms and these must be diagnosed and treated separately from the actual prostatitis symptoms. Sexual problems with the partner are frequently accompanied by significant consequences for the relationship (22).

Physical options include repetitive prostate massage or methods to apply energy to the prostate. There is not enough evidence for these approaches and they are therefore controversial.

If there are anatomical changes such as cysts in the prostate and these cause infravesicular obstruction, surgical procedures should be performed to remove the obstruction.

Table 4 shows the results of selected placebo-controlled studies.

Table 4. Selected studies on the treatment of chronic prostatitis / chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) with strict patient inclusion criteria—clearly defined patient population, randomized and placebo-controlled, study result evaluated with the Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI), published in peer-reviewed journals (1).

| Active drug | Therapy duration (days) | Patients | Change in the overall CPSI value | Treatment effect*1 | Author and year | ||

| Active substance | Placebo | Active substance | Placebo | ||||

| Levofloxacin | 42 | 35 | 45 | –5.4 | –2.9 | 2.5 | Nickel et al.; 2003 (e12) |

| Terazosin | 98 | 43 | 43 | –14.3*2 | –10.2 | 4.1 | Cheah et al.; 2003 (e13) |

| Alfuzosin | 168 | 17 | 20 | –9.9 | –3.8 | 6.1 | Mehik et al.; 2003 (e14) |

| Tamsulosin | 42 | 27 | 30 | N/A | N/A | 3.6 | Nickel et al.; 2004 (e15) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 42 | 49 | 49 | –6.2 | –3.4 | 2.8 | Alexander et al.; 2004 (e16) |

| Tamsulosin | 49 | –4.4 | 1.0 | ||||

| Tamsulosin + Ciprofloxacin | 49 | –4.1 | 0.7 | ||||

| Rofecoxib 25mg | 42 | 53 | 59 | –4.9 | –4.2 | 0.7 | Nickel et al.; 2003 (e17) |

| Rofexocib 50mg | 49 | –6.2 | 2.0 | ||||

| Pentosan polysulfate | 112 | 51 | 49 | –5.9 | –3.2 | 2.7 | Nickel et al.; 2000 (e18) |

| Finasteride | 168 | 33 | 31 | –3.0 | –0.8 | 2.2 | Nickel et al.; 2004 (e19) |

| Mepartricin | 60 | 13 | 13 | –15.0*2 | –5.0 | 10.0 | De Rose et al.; 2004 (e20) |

| Quercetin | 28 | 15 | 13 | –7.9*2 | –1.4 | 6.5 | Shoskes et al.; 1999 (e21) |

*1, treatment effect: mean change in overall CPSI score from the initial value at start of therapy in the active therapy group minus the placebo group;

*2, significant difference (p<0.05) between active substance and placebo; N/A, no data available

Asymptomatic prostatitis

It is currently accepted that patients with asymptomatic prostatitis do not require additional diagnosis or therapy (1). There are nevertheless several clinical situations in which additional measures may be indicated:

Asymptomatic prostatitis is frequently accompanied by an increase in PSA (23). In these cases, drug therapy (antibiotics, nonsteroidal antirheumatics) appears to reduce PSA (8). In such situations it is still necessary to take a biopsy to exclude prostatic carcinoma.

The role of asymptomatic prostatitis in the investigation of infertility is still unclear. There is some evidence that prostatitis can have an unfavorable effect on ejaculate parameters (24). It follows that antibiotic or anti-inflammatory treatment might improve ejaculate parameters (24).

Infection plays an important role in the clarification of hemospermia, particularly in younger patients (<40 years) (25).

Outlook

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis are clearly defined clinical pictures with unambiguous recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. As resistance to fluoroquinolones is increasing, therapy may be much less successful in future.

In the final analysis, the etiology of CP/CPPS is unclear and this is why there is a wide variety of possible different therapies. Treatment is based on symptomatic therapy. It is important for the patient that he should be informed as soon as possible about his condition, including the diagnostic steps and the possible therapies, and that there is a specific plan for his diagnosis and treatment. This is the only way to develop a trusting relationship between doctor and patient. This is especially important, as it often happens that several unsuccessful attempts are made at treatment, before an acceptable result is reached for the individual patient.

There will certainly be many changes in future in the management of asymptomatic prostatitis, as chronic prostatic inflammation may be important in several other conditions, such as prostatic carcinoma (4, 17), benign prostatic hyperplasia (3), or infertility (24). In theory, it may be possible in future that early diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic prostatitis could lead to the prevention of "inflammation-associated" prostatic carcinoma. In the therapy of infertility, prostatic infection might be one of the few exogenous causes which is treatable.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Rodney A. Yeates, M.A., Ph.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors Wagenlehner, Bschleipfer, Brähler, and Weidner declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Professor Naber reports links to Bayer, Bionorica, Eumedica Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi, MUCOS Pharma, Nano Vibronix, Ocean Spray Cranberries, OM Pharma, Peninsula/Johnson&Johnson/Janssen-Cilag, Pharmatoka, Protez, Sanofi-Aventis UroVision, and Zambon.

References

- 1.Schaeffer AJ, Anderson RU, Krieger JN. The assessment and management of male pelvic pain syndrome, including prostatitis. In: McConnell J, Abrams P, Denis L, et al., editors. Male Lower Uninary Tract Dysfunction, Evaluation and Management; 6th International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Disease. Paris: Health Publications; 2006. pp. 341–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Krauss H, et al. Chronic prostatitis: a thorough search for etiologically involved microorganisms in 1,461 patients. Infection. 1991;19(Suppl 3):119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01643680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nickel JC, Downey J, Young I, Boag S. Asymptomatic inflammation and/or infection in benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 1999;84(9):976–981. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Isaacs WB. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004;172:6–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000142058.99614.ff. discussion 11-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Jr, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282(3):236–237. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millan-Rodriguez F, Palou J, Bujons-Tur A, et al. Acute bacterial prostatitis: two different sub-categories according to a previous manipulation of the lower urinary tract. World J Urol. 2006;24(1):45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00345-005-0040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickel JC, Olson ME, Costerton JW. Rat model of experimental bacterial prostatitis. Infection. 1991;19(Suppl 3):126–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01643681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potts JM. Prospective identification of National Institutes of Health category IV prostatitis in men with elevated prostate specific antigen. J Urol. 2000;164(5):1550–1553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meares EM, Stamey TA. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol. 1968;5(5):492–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochreiter W, Ludwig M, Weidner W, et al. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index The German version. Urologe A. 2001;40(1):16–17. doi: 10.1007/s001200050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider H, Wilbrandt K, Ludwig M, Beutel M, Weidner W. Prostate-related pain in patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2005;95(2):238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weidner W, Anderson RU. Evaluation of acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis and diagnostic management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with special reference to infection/inflammation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(Suppl 1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penna G, Mondaini N, Amuchastegui S, et al. Seminal plasma cytokines and chemokines in prostate inflammation: interleukin 8 as a predictive biomarker in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2007;51(2):524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.016. discussion 533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludwig M, Vidal A, Diemer T, Pabst W, Failing K, Weidner W. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: seminal markers of inflammation. World J Urol. 2003;21(2):82–85. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wesselmann U, Burnett AL, Heinberg LJ. The urogenital and rectal pain syndromes. Pain. 1997;73(3):269–294. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickel JC, True LD, Krieger JN, Berger RE, Boag AH, Young ID. Consensus development of a histopathological classification system for chronic prostatic inflammation. BJU Int. 2001;87(9):797–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagenlehner FM, Elkahwaji JE, Algaba F, et al. The role of inflammation and infection in the pathogenesis of prostate carcinoma. BJU Int. 2007;100(4):733–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frazier HA, Spalding TH, Paulson DF. Total prostatoseminal vesiculectomy in the treatment of debilitating perineal pain. J Urol. 1992;148:409–411. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang YC, Yoshimura N, Wu M, et al. Intraprostatic capsaicin injection as a novel model for nonbacterial prostatitis and effects of botulinum toxin A. Eur Urol. 2007;51(4):1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach DW, Walker H. How important are prostaglandins in the urology of man. Urol Int. 1982;37:160–171. doi: 10.1159/000280813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csef HR, Rodewig K, Sökeland J. Somatoforme (funktionelle) Störungen des Urogenitalsystems. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2000;97(23):A 1600–A 1604. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith KB, Tripp D, Pukall C, Nickel JC. Predictors of sexual and relationship functioning in couples with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. J Sex Med. 2007;4(3):734–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stancik I, Luftenegger W, Klimpfinger M, Muller MM, Hoeltl W. Effect of NIH-IV prostatitis on free and free-to-total PSA. Eur Urol. 2004;46(6):760–764. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidner W, Wagenlehner FM, Marconi M, Pilatz A, Pantke KH, Diemer T. Acute bacterial prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: andrological implications. Andrologia. 2008;40(2):105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2007.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad I, Krishna NS. Hemospermia. J Urol. 2007;177(5):1613–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Schaeffer AJ, Anderson RU, Krieger JN. The assessment and management of male pelvic pain syndrome, including prostatitis. In: McConnell J, Abrams P, Denis L, et al., editors. Male Lower Uninary Tract Dysfunction, Evaluation and Management; 6th International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Disease. Paris: Health Publications; 2006. pp. 341–385. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Schaeffer AJ, Darras FS. The efficacy of norfloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis refractory to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and/or carbenicillin. J Urol. 1990;144(3):690–693. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Peppas T, Petrikkos G, Deliganni V, Zoumboulis P, Koulentianos E, Giamarellou H. Efficacy of long-term therapy with norfloxacin in chronic bacterial prostatitis. J Chemother. 1989;1(Suppl 4):867–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Pust RA, Ackenheil-Koppe HR, Gilbert P, Weidner W. Clinical efficacy of ofloxacin (tarivid) in patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis: preliminary results. J Chemother. 1989;1(Suppl 4):869–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Dalhoff A. Treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis with ciprofloxacin. Results of a one-year follow-up study. Am J Med. 1987;82:280–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Brahler E. Refractory chronic bacterial prostatitis: a re-evaluation of ciprofloxacin treatment after a median follow-up of 30 months. J Urol. 1991;146:350–352. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37791-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Pfau A. The treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Infection. 1991;3(Suppl 19):160–164. doi: 10.1007/BF01643689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Naber KG, Busch W, Focht J. Ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis: a prospective, non-comparative multicentre clinical trial with long-term follow-up. The German Prostatitis Study Group. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;14:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Naber KG. Lomefloxacin versus ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;20:18–27. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Bundrick W, Heron SP, Ray P, et al. Levofloxacin versus ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis: a randomized double-blind multicenter study. Urology. 2003;62:537–541. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Naber KG, Roscher K, Botto H, Schaefer V. Oral levofloxacin 500 mg once daily in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Nickel JC, Downey J, Clark J, et al. Levofloxacin for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: a randomized placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Urology. 2003;62:614–617. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Cheah PY, Liong ML, Yuen KH, et al. Terazosin therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2003;169:592–596. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000042927.45683.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Mehik A, Alas P, Nickel JC, Sarpola A, Helstrom PJ. Alfuzosin treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Urology. 2003;62:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Nickel JC, Narayan P, McKay J, Doyle C. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with tamsulosin: a randomized double blind trial. J Urol. 2004;171:1594–1597. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117811.40279.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Alexander RB, Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Ciprofloxacin or tamsulosin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:581–589. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Nickel JC, Pontari M, Moon T, et al. A randomized, placebo controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of rofecoxib in the treatment of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. J Urol. 2003;169:1401–1405. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000054983.45096.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Nickel JC, Johnston B, Downey J, et al. Pentosan polysulfate therapy for chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (chronic pelvic pain syndrome category IIIA): a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Urology. 2000;56:413–417. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Nickel JC, Downey J, Pontari MA, Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI. A randomized placebo-controlled multicentre study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of finasteride for male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category IIIA chronic nonbacterial prostatitis) BJU Int. 2004;93:991–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.De Rose AF, Gallo F, Giglio M, Carmignani G. Role of mepartricin in category III chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized prospective placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 2004;63:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI, Shahed A, Rajfer J. Quercetin in men with category III chronic prostatitis: a preliminary prospective double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 1999;54:960–963. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]