Abstract

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) accumulates on axonal varicosities and is primarily found as tetramers associated with a proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA). PRiMA is a small transmembrane protein that efficiently transforms secreted AChE to an enzyme anchored on the outer cell surface. Surprisingly, in the striatum of the PRiMA knock-out mouse, despite a normal level of AChE mRNA, we find only 2–3% of wild type AChE activity, with the residual AChE localized in the endoplasmic reticulum, demonstrating that PRiMA in vivo is necessary for intracellular processing of AChE in neurons. Moreover, deletion of the retention signal of the AChE catalytic subunit in mice, which is the domain of interaction with PRiMA, does not restore AChE activity in the striatum, establishing that PRiMA is necessary to target and/or to stabilize nascent AChE in neurons. These unexpected findings open new avenues to modulating AChE activity and its distribution in CNS disorders.

Introduction

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a pivotal enzyme in the cholinergic nervous system. Its primary function is to catalyze hydrolysis of released acetylcholine (ACh) and thus maintain homeostasis of this neurotransmitter in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Acute inhibition of AChE and the consequent enhanced cholinergic responses can be lethal due to the over-stimulation of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors by excess ACh, altering peripheral (autonomic and somatic motor) and CNS (control of respiration and seizure activity) functions (Taylor, 2006). Conversely, brain AChE is the target of contemporary therapy designed to compensate for neurotransmitter deficiency or achieve a functional balance of excitatory and inhibitory activity (Ballard et al., 2005).

AChE in brain is essentially found as a tetramer associated with a transmembrane protein, the proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA), in which the extracellular domain contains a proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) (Perrier et al., 2002). PRAD organizes AChE into tetramers (Bon et al., 1997) through interaction with tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization (WAT) domains on the catalytic subunits (Simon et al., 1998). The WAT domain is encoded by alternatively spliced exon 6 of the AChE gene, whereas exons 2–4 encode the catalytic domain common to all AChE species (Li et al., 1993).

The origins of AChE oligomers, control of their expression, and processing of AChE have been analyzed in cell culture. Recovery of AChE activity after inhibition with irreversible inhibitors (Rotundo and Fambrough, 1980a,b) and metabolic labeling (Lazar et al, 1984) were used to follow the dynamics of the maturation and the secretion of the oligomeric forms. Metabolic labeling of AChE with heavy amino-acids revealed the existence of several pools of monomers and tetramers with different stability (Lazar et al., 1984). These experiments clearly established that AChE is folded and processed in the endoplasmic reticulum to become active homomeric monomers and tetramers and is then secreted. Cells transfected with cDNA encoding only the AChER splice variant (exons 2, 3, and 4 and 3′ untranslated sequence) synthesize only monomers that are secreted into the medium, whereas transfection of the AChET variant cDNA (exons 2, 3, and 4 and 6 and 3′ untranslated sequence) reveals a diversity of mature species including monomers, dimers and tetramers (Massoulié, 2002). Deletion of the WAT domain from the AChET cDNA limits expression to monomeric species and increases the level of secreted AChE. This difference in secretion pathway routing is due to the presence of the aromatic residues in WAT domain involved in the tetramerization of AChE, precluding unassembled AChE from being shunted to degradation by the Endoplasmic Reticulum Associated Protein Degradation pathway (Belbeoc'h et al., 2003). When cotransfected with PRiMA or PRAD linked to a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) conjugation signal peptide, a portion of the AChE associates with PRAD and is anchored to the plasma membrane, while the level of secreted AChE decreases. In cell lines, AChE activity correlates with the quantity of transfected DNA, suggesting that AChE protein expression is proportional to its mRNA level, an observation consistent with the fact that a heterozygous (+/−) mouse from the AChE knock-out strain expresses half of the AChE found in the wild type (WT) mouse brain. (Li et al., 2000).

Given the essential role of brain AChE in physiological and pathological conditions, it becomes important to extend studies beyond cell culture to understand the cellular processing and disposition of AChE in vivo. Through deletions of the major anchoring structural subunit and its recognition region in the catalytic subunits of knock-out mice, we were able to analyze the biosynthesis and processing of AChE in vivo. Our observations of the knock-out mouse brain reveal a different control of the processing steps than is found in cell culture. Indeed, in the absence of PRiMA, we detect very low AChE activity and protein expression, but unaltered levels of AChE mRNA. Moreover, we show that residual AChE is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and localized to the nerve cell bodies of selected neurons. Finally, we demonstrate that the WAT domain is a signal in vivo for retention in the endoplasmic reticulum that, in the absence of PRiMA, prevents subsequent AChE processing in the Golgi apparatus and cellular localization in axons.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the PRiMA knock-out strain

A mouse cosmid library (129/ola cosmid library, RZPD) was screened using mouse PRiMA cDNA (Perrier et al., 2002). Sequencing and restriction mapping of the selected clone allowed the selection of NotI-KpnI and KpnI-KpnI fragments that were used to construct the recombinant vector containing PRiMA exons 1, 2, 3 (Fig. 1). The insert loxP-PGKneo-loxP was introduced between NcoI and NgoMIV sites in exon 3 to disrupt the coding sequence. The negative gene selective marker, diphtheria toxin A (Nagy et al., 1993) was introduced at the extremity of the long arm of the construct used for recombination. ES cells, transfected and maintained by GenOway, were screened by PCR. Two clones were selected and injected into blastocysts. Resulting male chimeric mice were crossed with B6D2 females, and agouti pups were screened for the presence of the neo gene. Homozygous mice are fertile, but they were obtained by mating heterozygotes to maintain the mixed B6D2 genetic background.

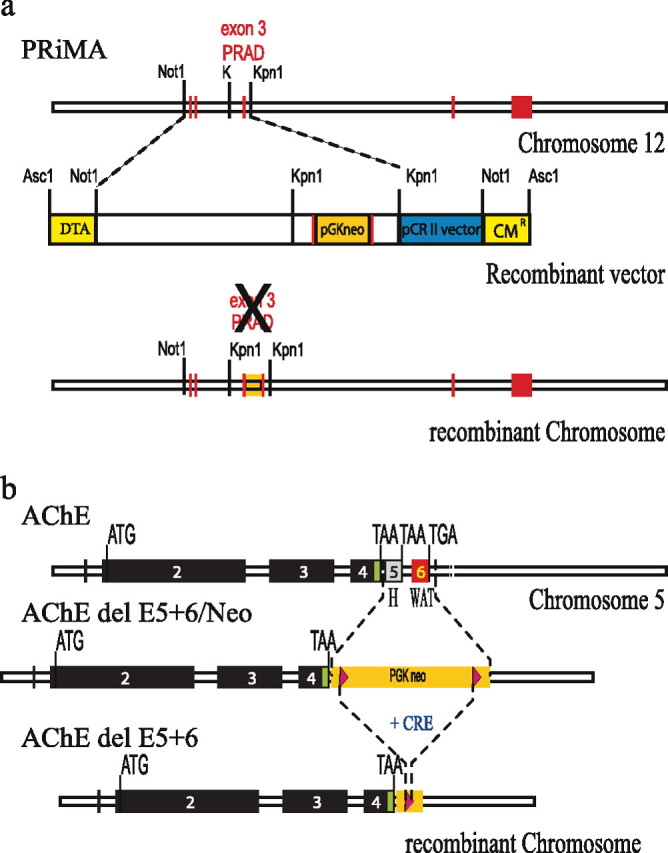

Figure 1.

Generation of PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mice. a, PRiMA (top), Map of the PRiMA gene in mouse chromosome 12. Exons are represented as red boxes. Exon 3 encodes the PRAD domain, the binding domain for AChE. Recombinant vector (middle), with the restriction sites used for cloning. DTA, diphtheria toxin A (yellow). CM, chloramphenicol resistance (yellow). pGKneo, gene encoding neomycin resistance (orange box), vector backbone (blue). Map of the recombinant chromosome (bottom). b, AChE (top), Map of the AChE gene in mouse chromosome 5. Exons encoding the catalytic domain are represented as black boxes (2–3-4) the alternative exons in gray (5) or red (6). Map of the recombinant chromosome after elimination of exons 5 and 6 (middle), showing the inserted gene encoding neomycin resistance (Camp et al., 2005). Map of the recombinant chromosome after elimination of exons 5 and 6 and deletion of the resistance gene by Cre recombinase (bottom) (Camp et al., 2005).

The production of AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mice was previously described (Camp et al., 2005) and parallels a more complete description of related knock-out strains (Camp et al., 2008). In the total AChE knock-out mouse strain, AChE exons 2, 3, and 4, which encode the catalytic domain of the enzyme, have been deleted (Li et al., 2000).

Knock-out mouse strains

Experiments were performed on four strains of mice: WT, mice nullizygous for PRiMA (PRiMA knock-out), mice nullizygous for AChE exons 5 + 6 (AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out), and the double knock-out that is nullizygous for both PRiMA and AChE exons 5 + 6. The AChE del E5 + 6 knock-outs were fed with milk (human baby milk: Perlargon 2, Nestlé) for 2 months after birth. This knock-out mouse strain displays a defect in thermoregulation during postnatal development (Sun et al., 2007), and the supplemental diet reduces weight loss (Duysen et al., 2002).

Genotypes were determined by PCR using the primers described in supplemental Table S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material. PCR analysis to determine genotype was performed with DNA from crude tissue extracts after alkaline hydrolysis using a mix of allele specific + and − primers and HotStart TaqDNA polymerase (Qiagen) with an annealing temperature of 65°C.

Experimental mice were 1- to 2-months-old and were of a genetic background mix equivalent to an F2 mating of B6 and D2 strains.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the policies of the French Agriculture and Forestry Ministry, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, and the University of California, San Diego's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (National Institutes of Health assurance number A3033-1; United States Department of Agriculture Animal Research Facility registration number 93-R-0437), and in accordance with the policy on the use of animals in neuroscience research issued by the Society for Neuroscience.

Extraction of striatal proteins and Western blotting

After perfusion with physiological saline and killing of the mice, striata were placed in ice-cold extraction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.3) containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors: 10 mm EDTA, 40 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin and 2 mm benzamidine. After homogenization in a Teflon-glass Dounce homogenizer for 3 min, the extracts were held on ice for 1 h followed by a centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min. The protein content of the supernatant was determined using the Bicinchoninic acid assay reagent kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Striatal proteins were then separated on NuPAGE Novex 7% Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions, and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot Transfer System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The blots were blocked overnight at 4°C in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% nonfat dried milk before incubation with a rabbit anti-AChE antibody (Jennings et al., 2003), diluted 1:1000 in the same TBS-T buffer, overnight at 4°C. The above referenced antibody eliminated several nonspecific bands at or near the size of AChE found with another AChE antibody (N19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that we tested. The extraneous bands were also found in extracts from the AChE nullizygote (data not shown). The blots were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare) or anti-sheep IgG antibodies (1/25,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, washed extensively and exposed to the chemiluminescent substrate ECL Plus (GE Healthcare).

Determination of AChE activity

Total AChE activity in the extracts or in gradients was assayed using 0.7 mm acetylthiocholine, and 0.5 mm 5,5-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) in the presence of 50 μm tetra(monoisopropyl)pyrophosphortetramide (iso-OMPA) (Sigma-Aldrich). The extracts were first incubated in the absence of acetylthiocholine for at least 20 min to block BChE and saturate the free sulfhydryl groups that interact with DTNB. The change in optical density was measured at 414 nm.

Tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry and histochemistry

The mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium chloral hydrate. At least four animals per group were subjected to transcardiac perfusion with a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde as previously described (Bernard et al., 1999). Sections from the neostriatum were cut on a vibrating microtome at 70 μm and collected in PBS. The sections were cryoprotected, freeze-thawed and stored in PBS until used.

Immunohistochemistry.

AChE was detected by immunohistochemistry using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against rat AChE [A63 (Marsh et al., 1984)]. AChE was detected at the light microscopic level on brain sections by immunofluorescence. The muscarinic receptor, subtype 2 (m2R), was detected by immunoreactivity using a monoclonal antibody raised in rat (MAB367, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents). Briefly, after perfusion-fixation, as described above, sections were incubated in 4% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 30 min and then in AChE antibody (1:1000) supplemented with 1% NDS for 15 h at room temperature. After a second wash, sections were incubated with cyanine 3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (to visualize AChE) or donkey anti-rat (to visualize m2R) secondary antibodies. After washing, the sections were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories) and examined in a confocal microscope. Immunoreactivity for the vesicular transporter of acetylcholine (VAChT) was used as a marker of striatal cholinergic interneurons expressing AChE. AChE and VAChT were simultaneously detected by double immunofluorescence. Sections were incubated in a mixture of antibodies to AChE (raised in rabbit, dilution: 1:1000) and to VAChT (raised in goat, dilution: 1:500, AB1578 Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) overnight at room temperature. After washing, the sections were incubated with cyanine 3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (AChE) or donkey anti-goat (VAChT) secondary antibodies. After washing, the sections were mounted in Vectashield. Immunoreactivity for cathepsin D (Cath D) was used as a marker of lysosomes. AChE and Cath D were simultaneously detected by double immunofluorescence. Sections were incubated in a mixture of antibodies to AChE (raised in rabbit, dilution: 1:1000) and to Cath D (raised in goat, dilution: 1:500, AB1578 Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) overnight at room temperature. After washing, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (AChE) or Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated donkey anti-goat (Cath D) secondary antibodies.

AChE was detected at the electron microscopic level using the pre-embedding immunogold method as previously described (Bernard et al., 1998). After treatment of sections with 1% osmium, dehydration and embedding in resin, ultrathin sections were cut, stained with lead citrate and examined in a Philips CM120 EM equipped with a camera (Morada, Soft Imaging System, Olympus).

Histochemical detection of AChE and BChE

AChE and BChE were detected by histochemistry using the Koelle–Friedenwald method modified by (Hammond et al., 1996). Free-floating brain sections including striatum were first incubated for 30 min in a mixture of 3 mm copper sulfate, 10 mm glycine, 500 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5, with 50 μm Iso-OMPA to inhibit BChE activity or 0.01 μm 1,5-bis(4-allyldimethylammoniumphenyl) pentan-3-one dibromide (BW284C51) (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit AChE activity. Sections were then incubated in the same mixture supplemented with 1 mm acetylthiocholine, the substrate of AChE or 1 mm butyrylthiocholine, the substrate of BChE, for 1 h (AChE) or 5 h (BChE) at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was converted with 160 mm sodium sulfite, pH 7.5, for 1 min and intensified using 588 μm silver nitrate, producing a brown precipitate. After washing in water, sections were fixed for 1 h with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed in water, dried on slides and mounted in Eukitt mounting medium. The labeling was observed at light microscopic level (Olympus BX61). To cover one half of the brain, six overlapping images were collected at 20× magnification and assembled with Image Proplus Software (MediaCybernetics).

Quantitative analysis of the distribution of AChE in neuronal compartments at the electron microscopic level

The subcellular distribution of AChE in the perikarya of striatal neurons of WT and knock-out mice was analyzed in immunogold-treated sections at the electron microscopic level. The analysis was performed on digitalized images of the negatives of micrographs at a final magnification of 3900 using the ImagePro Plus software (MediaCybernetics). Measurements were performed on four animals per group. An average of 10 perikarya per animal were analyzed. The immunoparticles were identified and counted in the cytoplasm of perikarya in association with subcellular compartments that encompassed the plasma membrane, the Golgi apparatus, the endoplasmic reticulum, multivesicular bodies and the outer nuclear membrane. Some immunoparticles were classified as associated with a sixth unidentified compartment because they were not associated with detectable organelles or they were associated with less well identified organelles not included above. Since the plasma and nuclear membrane length, the cell surface and the number of Golgi apparatuses were not the same in the sections from a single neuron, it was not possible to present the results as a mean of absolute values in each compartments for a single neuron. Therefore we calculated the density of AChE immunoparticles associated with the different subcellular compartments in each section of neuron. The immunoparticles associated with each compartment were counted and normalized to the membrane length (in micrometers) for the plasma membrane and the nuclear membrane, or normalized to the surface area of cytoplasm (square micrometers) for the endoplasmic reticulum and the unidentified compartment. For the Golgi apparatus, values are expressed as the number of immunoparticles per Golgi apparatus. To present the percentage variation of AChE in each compartment in a single histogram, we converted the data to number of particles per membrane length, number of particles per cytoplasmic surface or number of particles per Golgi apparatus. We gave arbitrary units of 100 to each control group and calculated the percentage variation in the knock-out mouse strains relative to this control value. The values from the immunogold experiments were analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA, followed by the post hoc analysis using the Bonferoni–Dunn test (Statview 5).

Sucrose density gradient analysis of AChE from striatal extracts

For these experiments, striata were extracted in 25 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.8 M NaCl, 1% CHAPS with protease inhibitors as described above. Sedimentation analyses of AChE forms were performed in 5–20% (w/v) sucrose gradients containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, 800 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA and 0.2% Brij-97 (polyoxyethylene 10 oleoyl ether, Sigma-Aldrich) or 1% CHAPS (Euromedex). The gradients were centrifuged at 38,000 rpm at 7°C for 18.5 h, using a SW41 rotor (Beckman Instruments). Each gradient was collected in 48 fractions and assayed for AChE activity. Fractions were calibrated with internal sedimentation markers [alkaline phosphatase (6.1S) and ß-galactosidase (16S)]. Sedimentation marker profiles were used to establish a linear relation between fraction number and Svedberg units.

RNA preparation and semiquantitative RT-PCR

Striata were dissected, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted and purified with an RNeasy Protect Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Samples were treated with DNase (Qiagen). RNA, 1–2 μg, was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT)20 primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Primers and amplicon sizes are described in supplemental Table S3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material.

Sequencing to analyze mRNA splicing in the mice used two primer pairs: s3-UT1 and s3-UT2 (positions depicted in Fig. 7). cDNA samples were amplified using 0.3 μm of the appropriate sense and antisense primers (see below) and following thermoprofile: 15 min at 95°C to activate the polymerase and 30 cycles [25 cycles for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) amplification] of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 59°C and 1 to 2 min 30 s at 72°C according to the length of the amplicon. The products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel and DNA was visualized with ethidium bromide. To identify each PCR product, the visible bands were extracted from the gel and amplified a second time for sequencing (Genome Express, France). For a quantitative evaluation of the different transcripts, varying amounts of the products of reverse transcription and numbers of PCR cycles were selected to compare the amplification of the products in the exponential phase of amplification. The PCR products were separated in 1.2% agarose gels, and gels were photographed (Vilbert Lourma). Digital outputs were analyzed. The relative amount of fluorescence for the different bands was normalized to size and to the GAPDH signal.

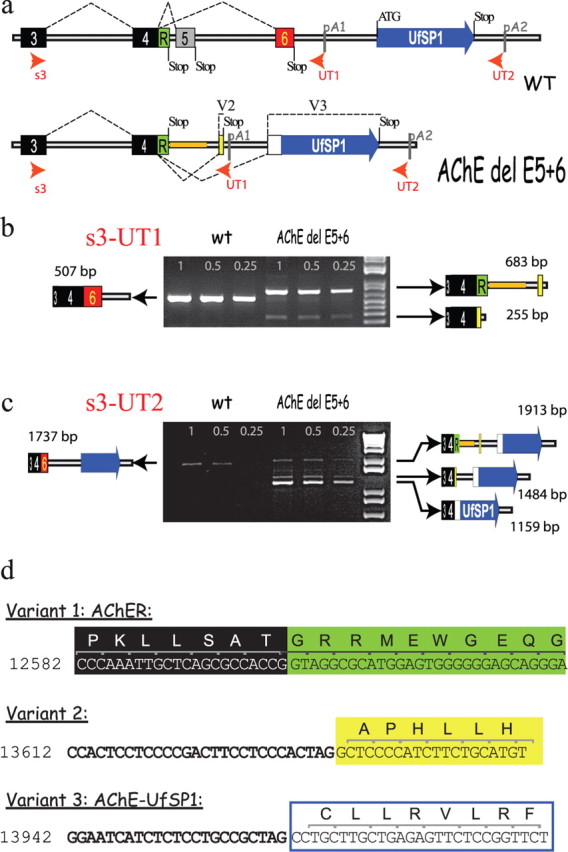

Figure 7.

Unique alternative splice variants in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mouse. a, Maps of the AChE gene with alternative splice variants for the WT and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out show that in the knock-out exons 5 and 6 are deleted and replaced by a short sequence used in the generation of the knock-out (orange bar). The predicted mature protein produced by the knock-out comes from AChER cDNA corresponding to the absence of splicing after exon 4, retaining 3′ genomic sequence. Two alternative splice variants, named variants 2 and 3, were identified in the AChE del E5 + 6−/− knock-out, and are shown. Note that there are two potential signals for polyadenylation. b, Semiquantitative RT-PCR with s3 and UT1 primers. In WT, s3-UT1 amplified a single PCR product of 507 bp (3 + 4+6) corresponding to the AChET mRNA isoform. As expected, this band is absent in AChE del 5 + 6 knock-out, but we detected two bands of 683 bp and 255 bp. The 683 bp band reflects the predicted unspliced AChER form (3 + 4+R), whereas the 255 bp product corresponds to splice variant 2. Quantification of the bands shows that AChER represents ∼20% of WT mRNA levels (set as 100%), while variant 2 represented only ∼3%. c, Semiquantitative RT-PCR with s3 and UT2 primers. We found a single band of 1737 bp in the WT (AChET) and a novel band of 1159 bp (variant 3, fusion of AChE with UfSP1) in the AChE del5 + 6 knock-out. d, The exact locations of splice acceptor sites found in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out by RT-PCR and sequencing are shown. Potential translated amino acid sequence is shown above the DNA sequence. Numbering comes from the reference sequence (AF312033.1) (Wilson et al., 2001).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real time PCR was performed using the absolute QPCR SYBR Green ROX Mix (ABgene) and the Taqman 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). PCRs were amplified with 0.2 μm of the primers (s3–as4); see supplemental Table S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material. PCRs were run with the following thermoprofile: 15 min at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Standard curves were generated for each pair of primers using serial dilutions of a RT reaction to verify linearity between log concentration and cycle threshold, and were used for logarithmic regression analysis of the samples. The relative expression level of each mRNA was calculated by measuring the cycle threshold in the log-linear phase and normalizing to GAPDH. The presence of a product of the correct size was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and melting curve analysis. PCR controls using RNA that had not been reverse transcribed did not produce an amplification product.

AChE expression in HEK 293 cells

AChE cDNAs containing part of exon 1, exons 2–4 and the novel splice sequences shown in Figure 7b were constructed in the expression vector pcDNA3 Invitrogen. HEK cells were plated ∼15 h before transfection at densities to achieve ∼80% confluence at transfection. DNA for transfections was purified by PEG precipitation and sedimentation in a CsCl gradient. The AChE plasmid of interest was cotransfected with the lipid reagent LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 4:1 with CMV β-galactosidase to correct for transfection efficiency. Cell media was replaced with DMEM (no serum) 8 h after transfection. Cells and media were harvested 48 h after transfection was initiated and analyzed for AChE and β-galactosidase activity (Camp et al., 2008).

Knock-out mouse phenotypes

Main phenotypic features where studied in adult PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mice and compared with the control animals. The WT mouse represented the normal physiological phenotype, while AChE−/− mouse was used as a model for severely compromised phenotype due to cholinergic impairment. All mice were housed under the same conditions at 22°C with ad libitum access to water and food (pellets or liquid food, depending on the strain) and with a fixed 12 h light/dark cycle. Phenotype was assessed for each mouse that was bred (encompassing >100 mice per gender per each knock-out strain) with special attention accorded to the features that are modified in the AChE−/− mouse (Duysen et al., 2002).

Physical appearance.

Physical appearance was determined by measuring the body weight and comparing the body size with that of control mice of the same age. Additionally, body posture, gait and involuntary motor movement were studied. Observations were confirmed in a blind tests in which different knock-out strains where placed together in the same cage and separated into the groups based on the same phenotypic features (blinded to their genotype).

Lifespan.

The AChE−/− mouse dies at an early age during a tonic phase of a grand mal seizures (Duysen and Lockridge, 2006). Therefore survival age and cause of death were followed in PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-outs.

Breeding.

The effect of liquid diet on the mortality of young knock-out mice, as well as on phenotype improvement was followed. The AChE−/− mouse has a defect in a thermoregulation due to downregulation of nicotinic receptors in sympathetic ganglia. Since maintenance of the temperature at ∼ 29°C improves the phenotype of AChE−/− mouse (Sun et al., 2007), the PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out strains were reared at a thermoneutral temperature (∼ 29°C). Resistance or inclination to bite was observed while handling the animals.

Behavior.

Vocalization and stereotypy were followed in undisturbed animals, handled animals, and animals placed in an unknown environment. Response to pain was observed by squeezing the tail with metal tweezers. Geotaxis was studied by placing a mouse head-down on the 45° tilted screen and checking its ability to turn head-up. Grip strength was tested on the metal screen rotated 180°. Cutoff time for geotaxis and grip strength was 60 s. Horizontal activity (rearing) was measured in the new environment (when the mouse was placed in a new cage).

Results

Genotype and phenotype of the AChE del E5 + 6 and PRiMA knock-out strains

To evaluate the importance of the anchoring of AChE in cholinergic function, we developed two knock-out mouse strains in which the interactions between PRiMA and AChE were disrupted, precluding heterologous subunit association. In both strains the catalytic domain of AChE remains intact. We generated a strain of knock-out mice by disruption of the PRAD domain of PRiMA (PRiMA knock-out, see Fig. 1 for gene deletion strategy) as well as an AChE knock-out in which the alternatively spliced exons encoding the C-terminal domains were deleted [AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out (Camp et al., 2008) and Fig. 1].

Although our study is primarily directed to the delineation of biosynthetic and trafficking steps in the assembly of heteromeric oligomers of AChE, distinctive differences in phenotypes of the PRiMA−/− and the AChE del E5 + 6−/− knock-out strains are of interest. In blind tests, all AChE−/− mice and all AChE del E5 + 6−/− mice were easily recognized based on physical appearance and behavior in the cage, whereas WT mice and PRiMA−/− mice were indistinguishable. While not identical, the AChE del E5 + 6−/− phenotype closely resembled that of the AChE−/− phenotype. PRiMA−/− mice did not differ from their WT siblings in any of the studied phenotypic features. The obvious phenotypic differences between these strains reflect that muscle AChE is not anchored at synaptic junctions through an interaction with PRiMA. AChE−/−mice have no muscle AChE, AChE del E5 + 6−/− mice have very low levels of AChE, but in the PRiMA mouse, synaptic muscle AChE is normal (Feng et al., 1999; Li et al., 2000; Camp et al., 2005). Supplemental Table S4 (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) contains further details of phenotypic comparisons.

The striatum: a model for the analysis of the maturation of AChE

To analyze the cellular disposition of AChE in vivo, we examined the processing of AChE in the striatum, a unique brain region, for the following reasons. First, the striatum contains the highest level of AChE in brain as revealed by the localized activity in Figure 2a (brown precipitate). Second, the striatum appears as an isolated structure that can be easily dissected for biochemical analysis (see below). Third, AChE is produced in abundance by a few scattered interneurons including cholinergic neurons easily identifiable by their large size (Fig. 2b) (Bernard et al., 1995). Fourth, the large volume of the cytoplasm and the well developed intracellular organelles of these interneurons facilitate quantifying AChE through the processing and secretion pathways and localizing AChE in subcellular organelles (endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, cell surface) at the electron microscopic level. In these neurons, mature AChE appears to be localized at the plasma membrane of axonal varicosities (Fig. 2c) and cell bodies (Fig. 2d, arrow).

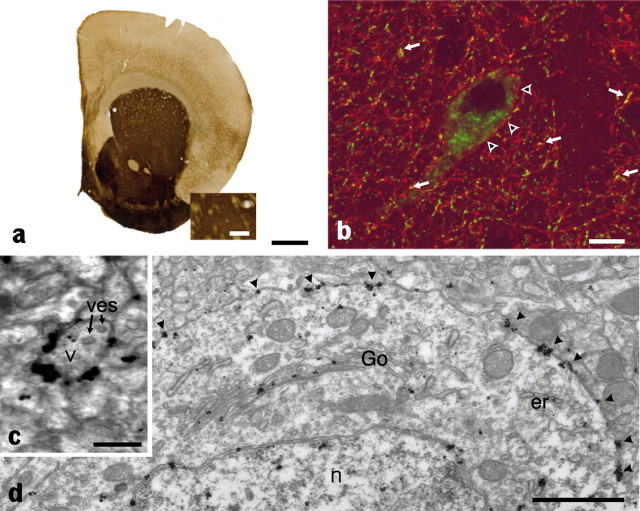

Figure 2.

AChE is located at the plasma membrane of perikarya and varicosities of cholinergic striatal interneurons in a control mouse strain. a, AChE activity in brain was revealed by thiocholine production as a brown precipitate. Staining shows a high level of AChE in the striatum; however, the subcellular localization is unresolved, because of limited spatial resolution of the colorimetric reaction. b, In contrast, immunohistochemical detection of AChE using confocal microscopy reveals that AChE (red) is present at the membrane of the cholinergic cell body (arrowheads), axon, and axonal varicosities. Axonal varicosities are identified by the vesicular transporter of acetylcholine (VAChT) immunoreactivity (green) (arrows). c, Analysis at the EM level shows AChE has obviously accumulated at the membrane of presynaptic varicosities (v) that are identified by the presence of vesicles (ves). d, AChE is also clearly present in the entire secretory pathway localized in the cell body [endoplasmic reticulum (er) and outer nuclear membrane, Golgi apparatus (Go), and plasma membrane (arrowheads); n identifies the cell nucleus]. Scale bars: a, 1 mm; enlargement, 0.25 mm; b, 10 μm; c, 250 μm; d, 1 μm.

Quantification of AChE molecular forms, activity, and expressed protein and mRNA levels

To evaluate the biochemical consequences of the mutations in PRiMA and AChE that prevent the anchoring of AChE, we quantified AChE at protein and mRNA levels in the striatum. Sucrose density gradients were used to analyze the molecular forms of tissue extracted AChE in the knock-out animals. In normal striatum, AChE is essentially organized as a PRiMA-linked amphiphilic tetramer (sedimentation coefficient of 10.5S in CHAPS which shifts to 8S in Brij due to the interaction between the amphiphilic domain and the detergent) (Perrier et al., 2002) (Fig. 3a, left). As expected, this tetramer is absent in the PRiMA knock-out, as well as in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out. In the PRiMA knock-out, a nonamphiphilic tetramer (10.5S and devoid of a Brij shift) is still present, in addition to an amphiphilic monomer (2.5S) and dimer (4.5S) (Fig. 3a, middle). In the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out, AChE is only found as a nonamphiphilic, soluble monomer (5S, not shifted by Brij) (Fig. 3a, right). Note the large difference in AChE activity scales between WT and knock-out animals.

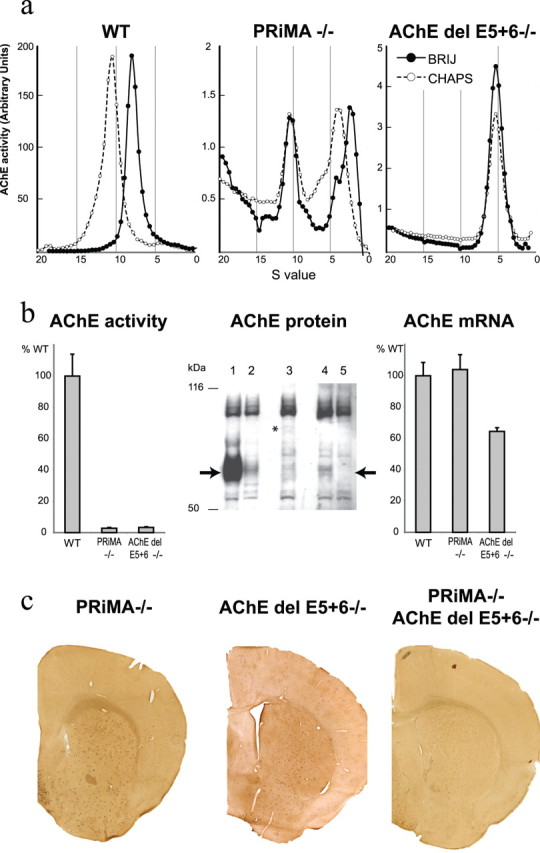

Figure 3.

PRAD/WAT is necessary to target AChE to the axon. a, Profiles of AChE activity separated in sucrose density gradients run with different detergents (●, Brij-97; ○, CHAPS). In WT striatum the AChE peak at 10.5S, which shifts in the presence of Brij detergent, corresponds to the amphiphilic tetramer containing PRiMA. In the striatum from the PRiMA knock-out strain, a peak at 10.5S, not shifted by Brij, corresponds to a nonamphiphilic tetramer (note the absence of the amphiphilic tetramer) and a peak at 4S, shifted in Brij, corresponds to an amphiphilic monomer. In the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out, AChE is only found as a single peak, not shifted by Brij, and corresponds to a nonamphiphilic monomer that likely is encoded by reading through into the retained intron after exon 4. b, Left, Total AChE activity extracted from striata of PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-outs is reduced to 2–3% of WT activity. Middle, Anti-mouse AChE antibody (Jennings et al., 2003) reveals a single specific band at 70 kDa in WT (lane 1) that is absent in the AChE−/− total knock-out (lane 5). In AChE del E5 + 6−/− (lane 3) and PRiMA−/− (lane 4) animals, the weak signal corresponds to that obtained when 5% WT extract is mixed with 95% nullizygote AChE−/− extract (lane 2). Right, The AChE mRNA level does not change in PRiMA−/− mice but is reduced by 35% in AChE del E5 + 6−/− mice. c, Histochemical detection of AChE activity in brains from PRiMA−/−, AChE del E5 + 6−/−, and double knock-out animals. AChE staining is limited to the cell bodies of a few scattered neurons, in contrast to the strong and diffuse staining in the WT strains (see Fig. 2a).

We quantified AChE activity in crude extracts from striatum in both knock-out strains and in each found only 2–3% of the AChE activity of the WT (Fig. 3b, left). To ascertain whether the reduction of activity corresponds to a reduction of the quantity of protein in these knock-outs, we analyzed the extracts by Western blot using anti-AChE antibodies (Fig. 3b, middle section). To assure the specificity of the detected signals, we used two controls. Lane 5 is a striatal extract from the AChE knock-out with a complete deletion of the catalytic domain (Li et al., 2000), which shows the absence of AChE in striatal extracts. Lane 2, a mixture of 5% WT and 95% AChE nullizygote striatal extracts, shows a light band of the correct molecular weight. As shown in Figure 3b, middle section, very low quantities of AChE protein were present in the striata from PRiMA−/− (lane 4) and AChE del E5 + 6−/− (lane 3) knock-out mice. Thus, the AChE protein levels observed in the Western blot correspond to the measured AChE activity. Quantification of the mRNA encoding AChE by real time RT-PCR (primers pairs are reported in supplemental Table S2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) did not reveal any changes in the level of AChE mRNA in PRiMA knock-out mice (Fig. 3b, right), indicating that the decrease of AChE did not result from reduction of AChE mRNA. This result suggests that processing and/or stabilization of AChE protein are affected in the absence of expressed PRiMA.

In contrast, AChE mRNA levels were reduced by ∼35% in the AChE del E5 + 6−/− knock-out strain. This reduction is far smaller than the >97% decrease observed in AChE activity, suggesting that the PRiMA/AChE interaction is necessary for stabilization of the AChE gene product. PRiMA mRNA levels were unchanged in the AChE del E5 + 6−/− knock-out (data not shown).

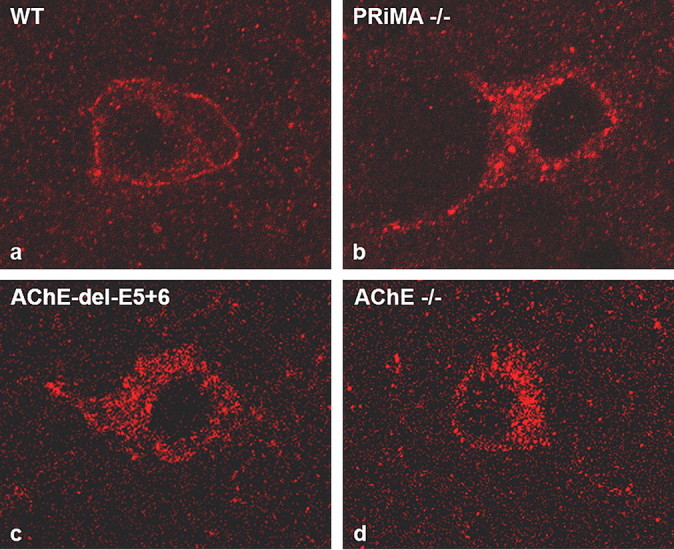

Cellular and subcellular distribution of AChE from light confocal and electron microscopy

To ascertain whether the very low activities of AChE in PRiMA and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mice are still detectable in the striatum and, if detectable, determine their regional localization, we stained brain sections histochemically. Interestingly, AChE is only visible in the cell bodies of scattered interneurons, the very neurons that produce AChE in the WT strain (Fig. 3c) (Bernard et al., 1995).

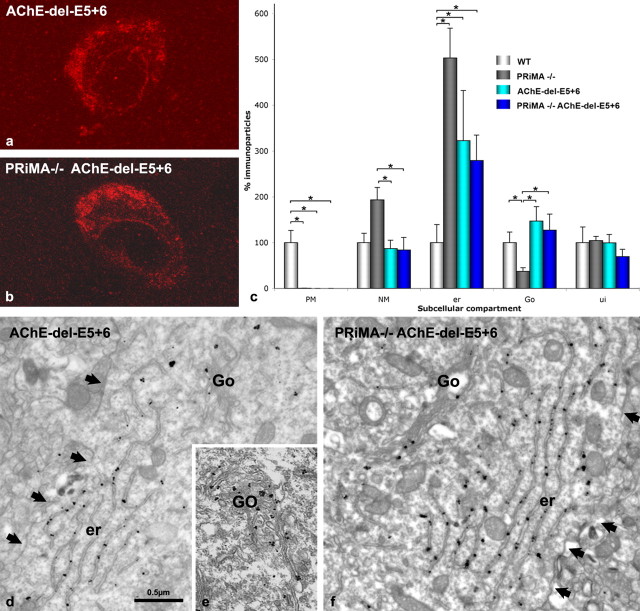

To detail the subcellular distribution of AChE in the interneurons, we examined AChE localization in the striata of the PRiMA knock-out. At the light microscopic level, AChE is completely absent from the axonal varicosities and is restricted to the cytoplasm of cell bodies (Fig. 4a,b). In addition, quantification of the subcellular distribution of AChE (Fig. 4c), based on EM images (Fig. 4d,e), reveals that AChE is neither detected at the plasma membrane nor in the extracellular space. Moreover, the density of immunoparticles for AChE is greatly increased in the endoplasmic reticulum and particle number is dramatically decreased in the Golgi apparatus in the PRiMA knock-out (Fig. 5), when compared with the WT strain.

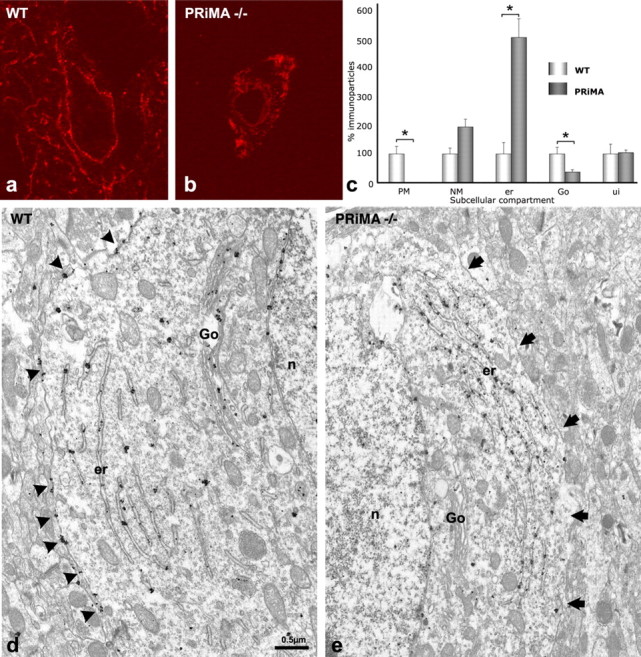

Figure 4.

In the absence of PRiMA, AChE accumulates in the endoplasmic reticulum and is not found associated with the plasma membrane or the Golgi apparatus. a, b, Confocal microscopy reveals that AChE, detectable in the membranes of cell bodies and in axonal varicosities in the WT mouse, is found exclusively in the cytoplasm of the cell bodies of the PRiMA−/− knock-out. c, Quantitative analysis of EM images (d, e). The number of immunoparticles associated with each compartment was counted and normalized to the length of the membrane in micrometers for the plasma membrane (PM) or the nuclear membrane (NM), or to the surface area in square micrometers of the cytoplasm, the endoplasmic reticulum (er), or the unidentified compartment (ui). For Golgi apparatus (Go), values are expressed as the number of immunoparticles per Golgi apparatus. Data correspond to the analysis of three homozygous mice of each genotype, 10 neurons per animal. Results are expressed in relation to the 100 arbitrary unit value used for each WT control. In d, arrowheads point to immunoparticles associated with the plasma membrane. In e, arrows show the plasma membrane.

Figure 5.

AChE immunolabeling in the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum of the PRiMA knock-out mouse. AChE was detected at the EM level in the striatum of PRiMA−/− knock-out mice by the pre-embedding immunogold method. Four examples of labeling in the cytoplasm of four different neurons illustrate the abundance of AChE immunoreactivity in the endoplasmic reticulum (er) and the near absence of labeling in the Golgi apparatus (Go).

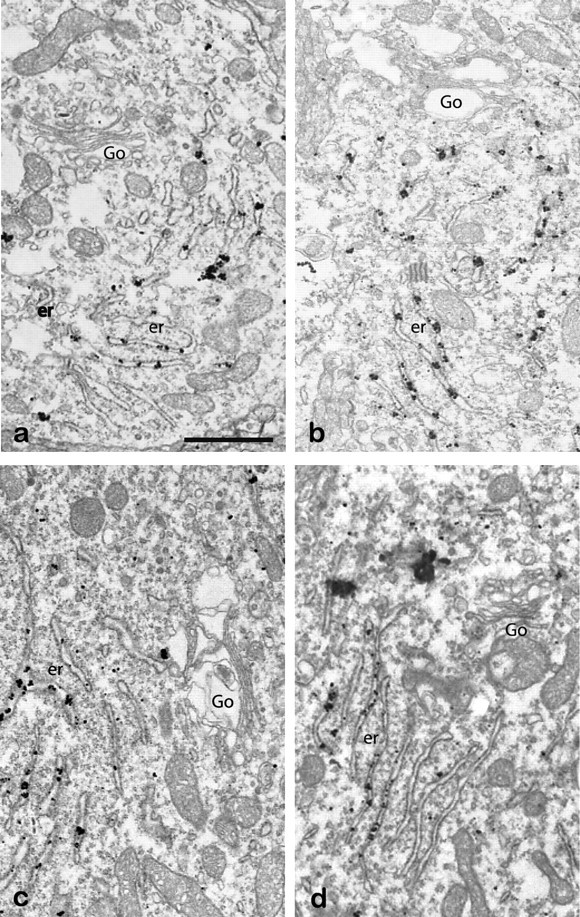

Retention of AChE in the endoplasmic reticulum and its virtual absence in the Golgi may depend directly upon the AChE WAT domain, the domain of interaction with PRiMA. To address this question, we bred the double knock-out strain, PRiMA/AChE del E5 + 6, and compared its subcellular distribution of AChE in the striatum with that found in the single AChE del E5 + 6 and the PRiMA knock-out strains. At the light microscopic level AChE is absent from axonal varicosities and is only detectable in the cell body cytoplasm of AChE del E5 + 6−/− and double knock-outs (Fig. 6a,b). The quantification of AChE at the EM level reveals that immunogold particle numbers for AChE are similar in the Golgi apparatus in WT, del E5 + 6−/−, and double knock-outs (Fig. 6c–f) in contrast to the very low level found in the PRiMA−/− knock-out (see Figs. 4c,e, 5). Since only the PRiMA knock-out would have a WAT domain that was not deleted or occluded by the PRiMA subunit, the WAT domain, when exposed, clearly serves as a strong retention signal for AChE in the endoplasmic reticulum, preventing the progression of AChE trafficking to the Golgi. No labeling was detected in Cath D immunopositive structures in PRiMA−/−, AChE del E5 + 6−/− and PRiMA−/−/AChE del E5 + 6−/− neurons, suggesting no degradation in lysosomes (data not shown).

Figure 6.

The AChE WAT domain targets AChE to the cell surface in WT mice and promotes retention of AChE in the endoplasmic reticulum of the PRiMA knock-out strain. a, b, Confocal microscopy shows AChE labeling in the striatum of (a) the AChE del E5 + 6−/− knock-out and (b) the double knock-out, PRiMA−/−/AChE del E5 + 6−/−. Similar staining is also seen in the PRiMA−/− knock-out (Fig. 4b). d–f, Electron microscopy shows an absence of immunoparticles at the plasma membrane of AChE del E5 + 6−/− (d) and PRiMA−/−/AChE del E5 + 6−/− (f) animals and the presence of AChE in the Golgi apparatus of the AChE del E5 + 6−/−mouse (e). Arrows point the plasma membrane. c, Quantification at the EM level reveals that the reduction in the number of immunoparticles for AChE in the Golgi apparatus (Go) compared with WT animals is only seen in the PRiMA knock-out, not in AChE del E5 + 6−/− or PRiMA−/−/AChE del E5 + 6−/− mice. However, immunoparticles for AChE accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum (er) in all three knock-outs. Data are analyzed as in Figure 4 and are compared using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni–Dunn test.

Novel mRNA splice variants in AChE del E5 + 6 do not produce functional AChE

Surprisingly, the accumulation of AChE in endoplasmic reticulum is still high in double and AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out strains compared with the WT. These observations suggest that in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out an unidentified sequence or subunit (unrelated to the WAT domain) serves to retain AChE in the endoplasmic reticulum. Because deletion of exon 5 or 6 unmasks the potential to reveal new 3′ proximal splice acceptor sites, we analyzed the sequences of the mRNAs extracted from the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out mouse brain. As illustrated in Figure 7, in addition to the expected AChER variant that is not spliced and retains the intron (Li et al., 1991), we identified two novel splice acceptor sites, generating variant 2 and variant 3 (Fig. 7). Using the primer pair, s3-UT1 (Fig. 7b), we found that AChER in the AChE del5 + 6 mouse corresponds to 20% of the amount of AChET in WT (splice to exon 6). AChER is the only transcript found naturally that does not involve expression of exon 5 or 6. RT-PCR using the primer pair s3-UT2 (Fig. 7c), however, produced a major band (variant 3) in the AChE del E5 + 6 strain. Based on this semiquantitative RT-PCR, we calculated that 1/3 of the total AChE mRNA in this strain is AChER mRNA and ∼2/3 is variant 3, whereas the more proximal splice producing variant 2 represents <5% of AChE mRNA. In the WT strain only AChET is present; the AChER variant is detectable but not quantifiable, and the variants 2 and 3 are absent.

Variant 3 encodes a protein composed of the catalytic domain of AChE and the sequence of UfSP1, an ubitiquin-fold modifier specific protease that has recently been characterized (Kang et al., 2007). This protein is detectable by Western blotting at a very low level (noted with a star in lane 3, Fig. 3b).

To ascertain whether a gene product of this splice variant can be expressed and processed in the cell, we constructed a cDNA chimera of the catalytic domain of AChE (exons 2, 3 and 4) with a downstream genomic sequence that corresponds to UfSP1 using the splice junction corresponding to variant 3 (Fig. 7d). We transfected plasmids encoding AChE-UfSP1 and AChER into HEK cells and compared AChE activity in media and cell extracts. As expected, transfection of AChER (variant 1) cDNA produced AChE activity, both in the cells and exported into the media. After 2 d, 95% of the AChE activity is in the media (30 OD/min/dish in the media and 0.8 OD/min/dish in the cells). AChE-UfSP1 (variant 3) cDNA transfection produced about half of the AChE activity (0.5 OD/min/dish) found in AChER transfected cells with no activity in the media. Activities were corrected for transfection efficiency. These findings suggest that the AChE-UfSP1 protein, arising from splice variant 3 in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out, is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and would not contribute to the cell surface activity.

Redistribution of BChE in the brain of the PRiMA knock-out mouse

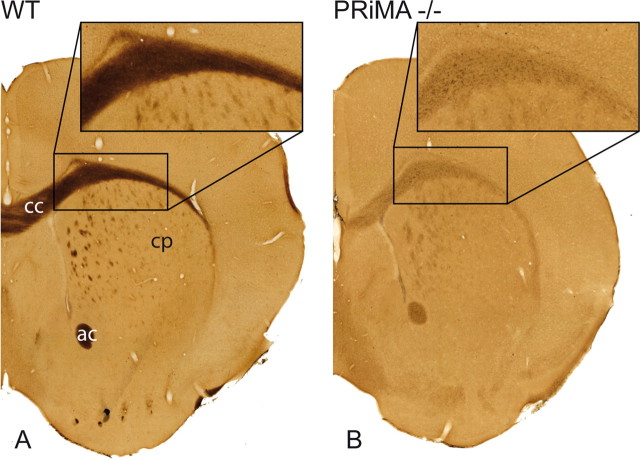

Because BChE is similar to the exon 6 spliced AChE species and consists of catalytic and WAT domains, we examined possible roles for PRiMA in the maturation of BChE. Immunohistochemistry was not possible due to the lack of a specific antibody to mouse BChE. To address the role of PRiMA in BChE maturation directly, we detected BChE activity in the brain after blockade of AChE activity. As a control, we conducted the same experiments on sections from the complete BChE knock-out strain (B. Li et al., 2008) (data not shown). BChE is abundant in white matter in the brain of the WT mouse. For example, in the corpus callosum, strong and uniform BChE staining is seen. In contrast, in PRiMA knock-out mice, BChE labeling is very faint and punctuate (Fig. 8), perhaps arising from BChE in glial cells. This suggests that intracellular processing of BChE to form molecules that are exported to the surface of brain cells requires expression of PRiMA.

Figure 8.

Histochemical detection of BChE in the anterior brain of the WT and PRiMA knock-out mouse. BChE activity in brain was revealed by thiocholine production as a brown precipitate. In the WT brain, BChE is expressed in white matter including corpus callosum (cc), white anterior commissure (ac), and white matter fascicles in the caudate–putamen (cp). In the PRiMA knock-out mouse, BChE labeling is markedly decreased and restricted to the cell body.

Functional adaptation to gene deletions: subcellular detection of the muscarinic m2 receptor by confocal microscopy

In the knock-out strains that we have characterized; PRiMA, AChE del E5 + 6 and the double knock-out, AChE is not detected in extracellular locations. To demonstrate that the absence of AChE staining around the nerve cell bodies corresponds to the absence of AChE activity and not a lack of sensitivity of our histochemical techniques, we examined the distribution of the muscarinic receptor, subtype 2 (m2R). We had previously shown that in the absence of AChE (the total AChE knock-out), m2Rs are no longer directed to the cell surface, but with enhanced ACh levels and stimulation, were shown to be trapped intracellularly (Bernard et al., 2006). As shown in Figure 9, in all three knock-out strains m2R is not found on the cell surface. Staining localized to intracellular locations also strongly supports the contention that m2Rs are retained within the cell. Hence in these three strains, the presumed enhanced levels of released ACh repress the processing of muscarinic receptors.

Figure 9.

PRiMA is involved in localizing the hydrolytic capacity of AChE, immunohistochemical detection of m2R in knock-out and control animals. a, In WT mice, m2R is normally accumulated at the membrane surface of the nerve cell body. d, We have previously shown that in AChE−/− mice m2R is not processed and delivered to the plasma membrane because excess residual ACh presumably overstimulates muscarinic receptors. b, c, In PRiMA (b) and AChE del E5 + 6 (c) knock-out mice, m2R was trapped in the cell as was seen with the total AChE knock-out strain. Even if some AChE were to reside in the extracellular space, enzyme activity is not sufficient for detection, nor is there sufficient activity to hydrolyze ACh and to influence m2R expression at the cell surface.

Discussion

The current view of AChE biosynthesis and cellular processing in brain suggests that the enzyme is either secreted into extracellular space (as tetramers and monomers) or is anchored to the plasma membrane when a trans-membrane spanning structural subunit, PRiMA, is coexpressed. Thus PRiMA is an accessory partner for the cellular disposition of AChE. In contrast, our findings provide new and somewhat unexpected insights into the biosynthetic processing of cholinesterases in brain. Surprisingly, the absence of PRiMA expression markedly reduces enzymatic activity and alters the neuronal distribution of AChE and BChE in the striatum. A hetero-oligomeric association between PRiMA and the AChE catalytic subunits is required for proper cellular and regional distribution in brain. Deletion of PRiMA prevents the processing of AChE through the secretory pathway. Using individual knock-out strains, one devoid of the anchoring protein PRiMA and the other devoid of the association domain of AChE that interacts with PRiMA, as well as the combination knock-out, we have demonstrated that PRiMA serves a dual function in vivo.

PRiMA involvement in AChE assembly and processing through the secretory pathway

The first unexpected function of PRiMA is its involvement in the early processing events of AChET through the secretory pathway in vivo, involving a specific interaction between the PRAD domain of PRiMA and the WAT domain of AChET. In contrast to the expression of AChET in transfected cell lines where AChET, when expressed alone, appears to be efficiently secreted, we show here that AChE in neurons is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and is no longer directed to the membrane through the Golgi apparatus in absence of PRiMA. Hence, the association of AChET with PRAD occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. Indeed, in the PRiMA knock-out, when the WAT domain is deleted (creating a double knock-out: del PRiMA/AChE del E5 + 6), AChE proceeds to the Golgi apparatus. Other quality control mechanisms that preclude secretion of unassembled subunits (Anelli and Sitia, 2008) help substantiate this potential role for PRiMA. In the case of AChE, a heterologous association between the catalytic subunits and a structural subunit is required for efficient processing.

The role of the WAT domain in the retention of AChE has been a matter of debate. Some in vitro data suggest that the WAT domain is not a retention signal for AChE. Specifically, it has been observed in fibroblasts transfected with a cDNA encoding AChET that dimers and tetramers of AChE are organized and secreted into the medium (Bon and Massoulié, 1997). Also, neuroblastoma cells, a cell line model for the neuron, produce and primarily secrete large quantities of AChE (Lazar et al., 1984). During P19 neuronal cell differentiation, the progressive expression of AChE recapitulates developmental expression, first monomers, followed by secreted tetramers and then anchored tetramers are produced sequentially (Coleman and Taylor, 1996). Metabolic labeling experiments and analysis of AChE forms during synthesis suggest that a homo-tetramer of AChE is first organized and that one set of dimers in the tetrameric assembly is associated with ColQ or PRiMA or is secreted (Rotundo et al., 1997; Camp et al., 2005). Mutagenesis of the WAT domain showed that the homo-tetramer can be organized and stabilized by endogenous disulfide bonds (Belbeoc'h et al., 2004). Despite these arguments, several in vitro studies support the contention that the WAT domain should be a retention signal. Monomers of AChET are not secreted in stably transfected cells but the AChE tetramer is found in abundance in the medium (Velan et al., 1994). Deletion or mutagenesis of aromatic residues of the WAT domain increases the secretion of AChE (Belbeoc'h et al., 2003). Coexpression of AChET with a PRAD containing protein increases AChE secretion from transfected cells (Bon et al., 1997; Noureddine et al., 2007). However, to date, the role for the WAT domain appeared to be an ancillary one in the processing of AChE. We demonstrate here that the WAT domain contains a strong retention signal in tissues in vivo. Finally, the organization of the AChE tetramer by PRiMA is the key element for the maturation of AChE in vivo in the brain, both targeting it to and stabilizing it in the axon.

PRiMA is essential for the targeting of AChE

The second function of PRiMA is to stabilize AChE and to target the enzyme to the membrane of axonal varicosities, the primary site of ACh hydrolysis by AChE. This function is revealed by the absence of AChE at the membrane of varicosities in the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out in which catalytically active AChE is produced, but cannot interact with PRiMA. In contrast to the WT mouse brain that produces only AChET [AChER is <1% of the total AChE transcript; see also Perrier et al. (2005)], quantification by RT-PCR revealed that AChER mRNA transcripts found in the AChE del E5 + 6−/− brain amounted to ∼20% of the AChET mRNA found in the WT animal (Fig. 7). As previously reported in cell culture, AChER is exported into the media of transfected cells. Surprisingly, the AChER protein represents only 2.5% of control levels suggesting that the secreted enzyme (AChER) does not replace the anchored enzyme (PRiMA/AChE).

Even if the enzyme is transiently secreted into the diffuse extracellular space surrounding the cell body, its catalytic capacity is too low or insufficiently localized to maintain m2R expression at the plasma membrane. The downregulation of the m2R from the plasma membrane has been shown previously in neurons from the AChE knock-out strain and likely results from increased levels of ACh (Bernard et al., 2003).

PRAD/WAT interaction: a key element for cholinesterase maturation in the endoplasmic reticulum

Our analysis reveals the essential functions of the PRAD/WAT interaction in the processing of AChE. Mammalian AChE and BChE contain very similar sequences in the WAT domain, as previously described (Blong et al., 1997; Massoulié, 2002). As suggested here, processing of AChE and BChE may be similar in brain. BChE, which is anchored by PRiMA in the brain, exhibits relocalization, probably into glial cells, when PRiMA is absent. Conversely, other PRAD containing proteins or peptides may interact with AChET and BChE as they are processed through the secretory pathway. ColQ contains a PRAD domain (Bon et al., 1997) that organizes AChE into a complex asymmetric molecule localized to the basal lamina of the neuromuscular junction (Krejci et al., 1997). In the absence of ColQ, AChE is not clustered in the basal lamina (Feng et al., 1999). Our results suggest that if the assembly process in the muscle and nerve is similar, AChE would be retained in the endoplasmic reticulum of muscle cells and not secreted. Recently, a proline rich peptide was found in the soluble tetramer of BChE purified from the serum, suggesting that the PRAD/WAT assembly is a general mechanism used to control the targeting of cholinesterases, whether soluble or membrane associated (H. Li et al., 2008).

Homeostasis of ACh

AChE localization by PRiMA participates in balancing the temporal response to the different excitatory, inhibitory and modulating neurotransmitters present in the striatum during development. Nicotinic and muscarinic receptors in brain regulate the release of other transmitters (MacDermott et al., 1999). Complete deletion of the AChE gene can be compatible with life but leads to the severely altered phenotype explained by compromised peripheral functions [e.g., muscle weakness: Duysen et al. (2002), or pathological thermogenesis: Sun et al. (2007)] as well as central compromised functions [developmental delay: Duysen et al. (2002)]. Either PRiMA targeted AChE does not play such a crucial role in development as had been believed or more likely, efficient adaptation mechanisms become manifest and respond to the lack of brain AChE and over stimulation by ACh during development. In any case, the phenotype of the PRiMA knock-out, when analyzed with the AChE del E5 + 6 knock-out, adds new perspectives to AChE expression and distribution in relation to brain cholinergic function and development.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (Grants P42ES010337 and R37-GM18360-35 to P.T.) and by grants from Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Neuroscience), and Bonus Quality Research Université Paris Descartes to E.K. E.K. was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and A.H. by AFM and ANR Neuroscience. We thank Dr. P. Guicheney, A. Rouche, and P. Bozin (Inserm U582, Institut de Myologie, Paris, France) for electron microscopy facilities.

References

- Anelli T, Sitia R. Protein quality control in the early secretory pathway. EMBO J. 2008;27:315–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard CG, Greig NH, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Enz A, Darvesh S. Cholinesterases: roles in the brain during health and disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:307–318. doi: 10.2174/1567205054367838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbeoc'h S, Massoulié J, Bon S. The C-terminal T peptide of acetylcholinesterase enhances degradation of unassembled active subunits through the ERAD pathway. EMBO J. 2003;22:3536–3545. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbeoc'h S, Falasca C, Leroy J, Ayon A, Massoulié J, Bon S. Elements of the C-terminal t peptide of acetylcholinesterase that determine amphiphilicity, homomeric and heteromeric associations, secretion and degradation. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1476–1487. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Legay C, Massoulie J, Bloch B. Anatomical analysis of the neurons expressing the acetylcholinesterase gene in the rat brain, with special reference to the striatum. Neuroscience. 1995;64:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00497-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Laribi O, Levey AI, Bloch B. Subcellular redistribution of m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in striatal interneurons in vivo after acute cholinergic stimulation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10207–10218. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-10207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Levey AI, Bloch B. Regulation of the subcellular distribution of m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in striatal neurons in vivo by the cholinergic environment: evidence for regulation of cell surface receptors by endogenous and exogenous stimulation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10237–10249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10237.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Brana C, Liste I, Lockridge O, Bloch B. Dramatic depletion of cell surface m2 muscarinic receptor due to limited delivery from intracytoplasmic stores in neurons of acetylcholinesterase-deficient mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;23:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Décossas M, Liste I, Bloch B. Intraneuronal trafficking of G-protein-coupled receptors in vivo. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blong RM, Bedows E, Lockridge O. Tetramerization domain of human butyrylcholinesterase is at the C-terminus. Biochem J. 1997;327:747–757. doi: 10.1042/bj3270747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. I. Oligomeric associations of T subunits with and without the amino-terminal domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3007–3015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Coussen F, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3016–3021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp S, Zhang L, Marquez M, de la Torre B, Long JM, Bucht G, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) gene modification in transgenic animals: functional consequences of selected exon and regulatory region deletion. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157–158:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp S, De Jaco A, Zhang L, Marquez M, De la Torre B, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase expression in muscle is specifically controlled by a promoter-selective enhancesome in the first intron. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2459–2470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4600-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman BA, Taylor P. Regulation of acetylcholinesterase expression during neuronal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4410–4416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysen EG, Lockridge O. Phenotype comparison of three acetylcholinesterase knockout strains. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30:91–92. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysen EG, Stribley JA, Fry DL, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Rescue of the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse by feeding a liquid diet; phenotype of the adult acetylcholinesterase deficient mouse. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;137:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Krejci E, Molgo J, Cunningham JM, Massoulié J, Sanes JR. Genetic analysis of collagen Q: roles in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase assembly and in synaptic structure and function. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond PI, Jelacic T, Padilla S, Brimijoin S. Quantitative, video-based histochemistry to measure regional effects of anticholinesterase pesticides in rat brain. Anal Biochem. 1996;241:82–92. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings LL, Malecki M, Komives EA, Taylor P. Direct analysis of the kinetic profiles of organophosphate-acetylcholinesterase adducts by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11083–11091. doi: 10.1021/bi034756x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Kim GR, Seong M, Baek SH, Seol JH, Bang OS, Ovaa H, Tatsumi K, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Chung CH. Two novel ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 (Ufm1)-specific proteases, UfSP1 and UfSP2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5256–5262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci E, Thomine S, Boschetti N, Legay C, Sketelj J, Massoulié J. The mammalian gene of acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22840–22847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar M, Salmeron E, Vigny M, Massoulié J. Heavy isotope-labeling study of the metabolism of monomeric and tetrameric acetylcholinesterase forms in the murine neuronal-like T 28 hybrid cell line. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:3703–3713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Stribley JA, Ticu A, Xie W, Schopfer LM, Hammond P, Brimijoin S, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Abundant tissue butyrylcholinesterase and its possible function in the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1320–1331. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.751320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Duysen EG, Carlson M, Lockridge O. The butyrylcholinesterase knockout mouse as a model for human butyrylcholinesterase deficiency. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1146–1154. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Schopfer LM, Masson P, Lockridge O. Lamellipodin proline rich peptides associated with native plasma butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Biochem J. 2008;411:425–432. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Camp S, Rachinsky TL, Getman D, Taylor P. Gene structure of mammalian acetylcholinesterase. Alternative exons dictate tissue-specific expression. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23083–23090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Camp S, Taylor P. Tissue-specific expression and alternative mRNA processing of the mammalian acetylcholinesterase gene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5790–5797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermott AB, Role LW, Siegelbaum SA. Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and the control of transmitter release. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:443–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D, Grassi J, Vigny M, Massoulié J. An immunological study of rat acetylcholinesterase: comparison with acetylcholinesterases from other vertebrates. J Neurochem. 1984;43:204–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb06698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoulié J. The origin of the molecular diversity and functional anchoring of cholinesterases. Neurosignals. 2002;11:130–143. doi: 10.1159/000065054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noureddine H, Schmitt C, Liu W, Garbay C, Massoulié J, Bon S. Assembly of acetylcholinesterase tetramers by peptidic motifs from the proline-rich membrane anchor, PRiMA: competition between degradation and secretion pathways of heteromeric complexes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3487–3497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier AL, Massoulié J, Krejci E. PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron. 2002;33:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier NA, Salani M, Falasca C, Bon S, Augusti-Tocco G, Massoulié J. The readthrough variant of acetylcholinesterase remains very minor after heat shock, organophosphate inhibition and stress, in cell culture and in vivo. J Neurochem. 2005;94:629–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotundo RL, Fambrough DM. Synthesis, transport and fate of acetylcholinesterase in cultured chick embryos muscle cells. Cell. 1980a;22:583–594. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotundo RL, Fambrough DM. Secretion of acetylcholinesterase: relation to acetylcholine receptor metabolism. Cell. 1980b;22:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotundo RL, Rossi SG, Anglister L. Transplantation of quail collagen-tailed acetylcholinesterase molecules onto the frog neuromuscular synapse. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:367–374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S, Krejci E, Massoulié J. A four-to-one association between peptide motifs: four C-terminal domains from cholinesterase assemble with one proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) in the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:6178–6187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Lee CJ, Shin HS. Reduced nicotinic receptor function in sympathetic ganglia is responsible for the hypothermia in the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. J Physiol. 2007;578:751–764. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase agents. In: Brunton L, editor. Goodman and Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Velan B, Kronman C, Flashner Y, Shafferman A. Reversal of signal-mediated cellular retention by subunit assembly of human acetylcholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22719–22725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MD, Riemer C, Martindale DW, Schnupf P, Boright AP, Cheung TL, Hardy DM, Schwartz S, Scherer SW, Tsui LC, Miller W, Koop BF. Comparative analysis of the gene-dense ACHE/TFR2 region on human chromosome 7q22 with the orthologous region on mouse chromosome 5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1352–1365. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.6.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]