Abstract

The present research examined whether 5- to 6.5-month-old infants would hold different expectations about various physical events involving a box after receiving evidence that it was either inert or self-propelled. Infants were surprised if the inert but not the self-propelled box: reversed direction spontaneously (Experiment 1); remained stationary when hit or pulled (Experiments 3 and 3A); remained stable when released in midair or with inadequate support from a platform (Experiment 4); or disappeared when briefly hidden by one of two adjacent screens (the second screen provided the self-propelled box with an alternative hiding place; Experiment 5). On the other hand, infants were surprised if the inert or the self-propelled box appeared to pass through an obstacle (Experiment 2) or disappeared when briefly hidden by a single screen (Experiment 5). The present results indicate that infants as young as 5 months of age distinguish between inert and self-propelled objects and hold different expectations for physical events involving these objects, even when incidental differences between the objects are controlled. These findings are consistent with the proposal by Gelman (1990), Leslie (1994), and others that infants endow self-propelled objects with an internal source of energy. Possible links between infants’ concepts of self-propelled object, agent, and animal are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Investigations of early physical reasoning over the past 20 years have revealed that, by 6 months of age, infants already possess rich expectations about physical events (e.g., Aguiar & Baillargeon, 2002; Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Baillargeon, Spelke, & Wasserman, 1985; Durand & Lécuyer, 2002; Goubet & Clifton, 1998; Hespos & Baillargeon, 2001b, 2008; Hofstadter & Reznick, 1996; Hood & Willatts, 1986; Kochukhova & Gredebäck, 2007; Kotovsky & Baillargeon, 1998; Lécuyer & Durand, 1998; Leslie, 1984a; Leslie & Keeble, 1987; Luo & Baillargeon, 2005b; Luo, Baillargeon, Brueckner, & Munakata, 2003; Needham & Baillargeon, 1993; Ruffman, Slade, & Redman, 2005; Sitskoorn & Smitsman, 1995; Spelke, Breinlinger, Macomber, & Jacobson, 1992; Spelke, Kestenbaum, Simons, & Wein, 1995a; von Hofsten, Kochukhova, & Rosander, 2007; Wang, Baillargeon, & Brueckner, 2004; Wang, Baillargeon, & Paterson, 2005; Wilcox, 1999; Wilcox, Nadel, & Rosser, 1996). Some of these experiments used inert objects (e.g., inert balls, boxes, cylinders, toy cars, toy lions, and toy bugs), whereas others used self-propelled objects (e.g., self-propelled balls, boxes, cylinders, toy carrots, toy mice, and toy bears). The choice of inert or self-propelled objects was typically made for reasons of methodological convenience and had little effect on the results. For example, investigations focusing on occlusion events found that infants aged 3.5 months and older expect an object, whether inert or self-propelled, (1) to continue to exist when behind an occluder; (2) to follow a continuous, unobstructed path when behind an occluder; and (3) to remain partly visible when taller or wider than the occluder (e.g., Baillargeon, 1986, 1987; Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Baillargeon & Graber, 1987; Hespos & Baillargeon, 2001a, 2006; Hofstadter & Reznick, 1996; Kochukhova & Gredebäck, 2007; Luo & Baillargeon, 2005b; Luo et al., 2003; Ruffman et al., 2005; Spelke et al., 1992; von Hofsten et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004; Wilcox, 1999; Wilcox et al., 1996; for a possible exception we return to later on, see Kuhlmeier, Bloom, & Wynn, 2004).

On the basis of such results, we might be tempted to conclude that young infants’ expectations about physical events are framed in terms of a single category of objects, namely, physical objects. Such a conclusion would be premature, however, for the following reasons. First, many investigations of infants’ physical reasoning to date have focused on physical events where even adults would hold similar expectations for inert and self-propelled objects. Second, when experiments have involved physical events where different expectations could conceivably have arisen for inert and self-propelled objects, no such comparison was performed (or indeed required), because it fell outside of the investigators’ expressed research agenda.

An important exception to this last generalization comes from work by Kosugi, Saxe, Woodward, and their colleagues (e.g., Kosugi & Fujita, 2002; Kosugi, Ishida, & Fujita, 2003; Saxe, Tenenbaum, & Carey, 2005; Saxe, Tzelnic, & Carey, 2007; Spelke, Phillips, & Woodward, 1995b; Woodward, Phillips, & Spelke, 1993). This research examined whether infants aged 7 months and older recognize that (1) a self-propelled object can initiate its own motion, whereas an inert object cannot, and (2) an inert object can be set into motion only through contact with another object. In one experiment, for example, 7-month-old infants were assigned to an inert or a self-propelled condition (Spelke et al., 1995b; Woodward et al., 1993). The infants in the inert condition were habituated to a videotaped event involving two large (human-sized) wheeled blocks that differed in height, width, shape, pattern, and color. To start, one block moved into view on the left side of the television monitor and disappeared behind the left edge of a large occluder at the center of the monitor; the second block was partly visible at the right edge of the occluder. After an appropriate interval, the second block moved to the right and disappeared on the right side of the monitor. The entire event sequence was then repeated in reverse. Following habituation, the occluder was removed, and the infants saw two test events in which the blocks moved as before; the only difference between the events had to do with what happened during the previously occluded portion of the blocks’ trajectories. In one event (contact event), the moving block collided with the stationary block and set it into motion; in the other event (no-contact event), the moving block stopped short of the stationary block, which then set off on its own. The infants in the self-propelled condition saw identical events except that the two blocks were replaced with a man and a woman who walked along the same path as the blocks.

The infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the no-contact than at the contact event, whereas those in the self-propelled condition looked about equally at the two events. These and control results suggested three conclusions. First, because there was no clear indication that the blocks were self-propelled during the habituation trials (it was unclear what caused them to roll into view on either side of the television monitor), the infants categorized them as inert; infants thus appear to hold the default assumption that a novel object is inert unless given unambiguous evidence that it is self-propelled (see also Luo & Baillargeon, 2005a). Second, the infants understood that inert objects can be set into motion only through contact with other objects, and thus they inferred that one block must be colliding with the other block behind the occluder. Third, the infants realized that humans are self-propelled objects, which can move at will.1

The preceding results suggest that by 7 months of age infants hold different expectations for at least some physical events involving inert and self-propelled objects. Where might these different expectations come from? One hypothesis, put forth by Gelman (1990; Gelman & Spelke, 1981; Gelman, Durgin, & Kaufman, 1995; Subrahmanyam, Gelman, & Lafosse, 2002) and Leslie (1984a, 1994a, 1995; Leslie & Keeble, 1987), is that part of the skeletal causal framework infants bring to bear when interpreting physical events is a fundamental distinction between inert and self-propelled objects. When infants watch a novel object begin to move or change direction, their physical-reasoning system attempts to determine whether the change in the object’s motion state is caused by forces internal or external to the object. According to Leslie (1994), “the more an object changes motion state by itself and not as a result of external impact, the more evidence it provides, the more likely it is, that it is [self-propelled]” (p. 133). An object that is judged to be self-propelled is endowed with an internal source of energy. A self-propelled object can use its internal energy both directly to control its own motion and indirectly (through the application of force) to control the motion of other objects. We refer to this hypothesis as the internal-energy hypothesis, for ease of communication.

If the internal-energy hypothesis is correct, then young infants may hold different expectations for physical events involving inert and self-propelled objects whenever they believe that an application of internal energy can bring about a different outcome. Thus, infants may be surprised to see an inert but not a self-propelled object remain stationary when hit, if they assume that the self-propelled object can use its internal energy to resist efforts to move it. In contrast, infants may be surprised to see an inert or a self-propelled object disappear into thin air, if they realize that no application of internal energy can result in the disappearance of the self-propelled object.

The preceding reasoning led us to undertake an extensive series of experiments to systematically compare 5- to 6.5-month-old infants’ responses to various physical events involving an inert or a self-propelled object. To control for extraneous factors, the inert and the self-propelled object used in the experiments was the same small box. During familiarization, half the infants were given evidence that the box was self-propelled (e.g., the box initiated its own motion in plain view); the other infants were given no such evidence and so presumably categorized the box as inert. Whether self-propelled or not, the box always moved in exactly the same manner: its motion was actually controlled by a mechanical device, to ensure uniformity across trials and conditions. During test, the infants saw various physical events involving the box. The experiments tested whether infants (1) would view the outcomes of some events as surprising when they categorized the box as inert but not as self-propelled, because in the latter case they could infer that the box had used its internal energy to bring about the observed outcomes; and (2) would view the outcomes of other events as surprising whether they categorized the box as inert or as self-propelled, because they realized that no application of internal energy could explain the observed outcomes.

We speculated that evidence that infants hold different expectations for some but not other physical events involving inert and self-propelled objects, under these controlled conditions, would be important for three reasons. First, it would provide strong evidence that infants’ expectations about physical events are framed in terms of not one but two categories of objects: inert and self-propelled objects. Second, it would support the internal-energy hypothesis proposed by Gelman and Leslie (e.g., Gelman, 1990, Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995). Finally, it would lead to interesting questions about possible links between the concept of self-propelled object in the present research (see also Baillargeon, Wu, Yuan, Li, & Luo, in press-b), the concept of agent in the psychological-reasoning literature (e.g., Csibra, 2008; Johnson et al., 2008; Johnson, Shimizu, & Ok, 2007; Luo & Baillargeon, 2005a), and the concept of animal in the conceptual-development literature (e.g., Carey, 1985; S. A. Gelman & Gottfried, 2005; Mandler, in press; Subrahmanyam et al., 2002). We return to these issues in the General Discussion.

2. Experiment 1: Can an inert or a self-propelled object spontaneously reverse direction?

We have seen that infants hold different expectations for the onset of inert and self-propelled objects’ (horizontal) displacements: they realize that a self-propelled object can initiate its own motion, whereas an inert object cannot (e.g., Kosugi & Fujita, 2002; Kosugi et al., 2003; Saxe et al., 2005, 2007; Spelke et al., 1995b; Woodward et al., 1993). Do infants also hold different expectations for the path inert and self-propelled objects are likely to follow once in motion? As adults, we recognize that a self-propelled object can use its internal energy to change direction at will; in contrast, we expect an inert object to follow a smooth path, without abrupt changes in direction. Thus, we would be surprised if a ball rolling on a table changed direction as it reached each corner so as to follow the perimeter of the table; with inert objects, abrupt changes in direction cannot be achieved without external impact.2 In Experiment 1, we asked whether 5-month-old infants would expect an inert but not a self-propelled object to follow a smooth path, with no abrupt change in direction.

Previous research suggested that young infants are not surprised when an inert object abruptly deviates from its initial path. Spelke et al. (1994) habituated 4- and 6-month-old infants to an event in which a ball rested in the front right corner of a large table (here and throughout this article, events are described from the infants’ perspective); a horizontal screen hid the left half of the table. An experimenter’s hand hit the ball, which then rolled diagonally across the table until it disappeared under the screen at the center of the table. Next, the screen was removed to reveal the ball resting in the back left corner of the table, further along its pre-occlusion trajectory. Following habituation, the infants saw a linear and a non-linear test event. The linear event was similar to the habituation event except that the ball started from the back right corner of the table; it rolled diagonally across the table until it disappeared under the screen and was revealed resting in the front left corner of the table, as expected. In the nonlinear event, the ball again started from the back right corner of the table and rolled diagonally across the table; however, when the screen was removed, the ball rested in the same back left corner as in the habituation event, as though it had performed a 90° turn when under the screen. The infants did not look longer at the nonlinear than at the linear event, and Spelke and her colleagues concluded that young infants do not expect an inert object, once in motion, to follow a smooth path.

However, other interpretations of these negative results were possible. Because of limitations in the apparatus used to implement the experimental design, the infants were actually presented with a more subtle violation than is suggested by the preceding description. In reality, most of the left side of the table was filled with a large insert with a central indentation in its right edge; the ball came to rest in the front or back corner of this indentation. Thus, rather than seeing the ball at rest in the front or back left corner of the table at the end of the test events (a large and salient difference), the infants saw the ball at rest in the front or back corner of the indentation (a smaller and perhaps less salient difference). This arrangement might have made it difficult for the infants to determine whether or how far the ball had deviated from its pre-occlusion trajectory. Keeping in mind that young infants might be limited in their ability to represent trajectories, we presented the infants in Experiment 1 with a very salient violation: a full reversal, in plain view.

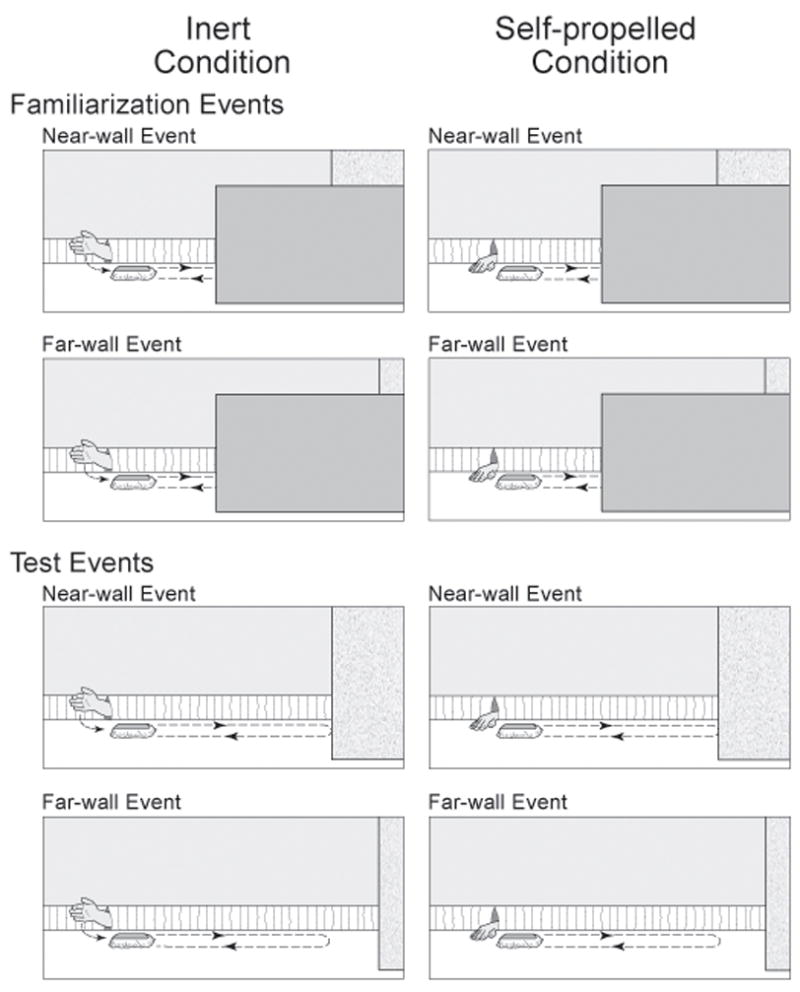

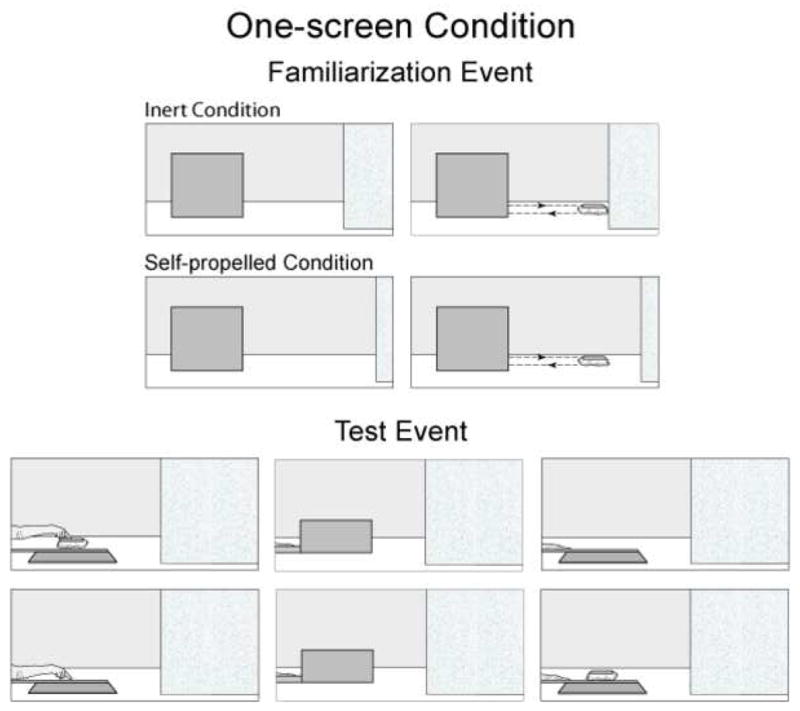

The infants were assigned to an inert or a self-propelled condition (see Fig. 1). The infants in the inert condition sat in front of a large apparatus whose right side was occluded by a large screen; a small box was visible on the left side of the apparatus. In the familiarization event, an experimenter’s gloved hand hit the box, which then moved to the right until it disappeared behind the left edge of the screen. After a few seconds, the box reappeared from behind the same edge of the screen and returned to its starting position. Following familiarization, the screen was removed, and the infants watched two test events. In one, the hand again hit the box, which moved to the right until it hit a wall partition at the right end of the apparatus; the box then reversed direction, as though bouncing back, and returned to its starting position (near-wall event). In the other event, the wall partition was placed farther to the right; because the box moved exactly as before, it now reversed direction on its own, without hitting the wall partition (far-wall event). Since the wall partition changed position in the near- and far-wall test events, it was also placed in the same two positions on alternate familiarization trials; however, because the screen was in place during these trials, only the very top of the wall partition was visible above the screen (see Fig. 1). The infants in the self-propelled condition saw identical near- and far-wall familiarization and test events except that the box initiated its own motion: the hand remained stationary on the apparatus floor.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the familiarization and test events in Experiment 1

Our reasoning was as follows. If at 5 months infants tend to view an object as inert unless given unambiguous evidence that it is not (e.g., Luo & Baillargeon, 2005a), then the infants in the inert condition should categorize the box as inert during the familiarization trials because (1) they saw the hand set it in motion, and (2) they had no evidence as to what caused its reversal behind the screen. In contrast, the infants in the self-propelled condition should categorize the box as self-propelled because they saw it initiate its own motion.

Furthermore, if at 5 months infants (1) endow self-propelled but not inert objects with internal energy (e.g., Gelman, 1990; Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995), and (2) expect an object to follow a smooth path unless a force—either internal or external to the object—intervenes to bring about a change, then the infants in the inert and self-propelled conditions should respond differently to the test events. In the inert condition, the infants should be surprised when the box reversed direction spontaneously but not when it reversed direction after hitting the wall partition; this impact provided an external cause for the abrupt change in the box’s trajectory. The infants should thus look reliably longer at the far- than at the near-wall event. In the self-propelled condition, in contrast, the infants should not be surprised when the box reversed direction either spontaneously—it could use its internal energy to do so—or after hitting the wall partition. The infants should thus look about equally at the far- and near-wall events.

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

Participants were 32 healthy term infants, 16 male and 16 female, ranging in age from 4 months, 16 days to 5 months, 10 days (M = 4 months, 28 days, SD = 7.5 days). Another 11 infants were tested but eliminated from the analyses, 5 because they were distracted (3), fussy (1), or overly active (1), 4 because of observer difficulties, and 2 because they looked for the maximum amount of time allowed (60 s) on all four test trials. Half the infants were randomly assigned to the inert condition (8 male and 8 female; M = 4 months, 28 days, SD = 7.0 days), and half to the self-propelled condition (M = 4 months, 28 days, SD = 8.3 days).

The infants’ names in this and in the following experiments were obtained primarily from purchased mailing lists and from birth announcements in the local newspaper. Parents were contacted by letters and follow-up phone calls; they were offered reimbursement for their transportation expenses but were not compensated for their participation.

2.1.2. Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of a wooden display booth 125 cm high, 164 cm wide, and 78 cm deep that was positioned 76 cm above the room floor. The infant faced an opening 46 cm high and 157.5 cm wide in the front wall of the apparatus; between trials, a curtain consisting of a muslin-covered frame 56.5 cm high and 163 cm wide was lowered in front of this opening. The side walls of the apparatus were painted white and the floor was covered with black contact paper. The back wall was constructed of foam board and was covered with a grey granite-patterned contact paper; at the bottom of the wall, along its entire width, was an opening 15 cm high that was filled with a gray fringe. The experimenter used this opening to introduce her right hand (covered with a golden spandex glove) into the apparatus.

The box used in the experiment was 5 cm high, 19.5 cm wide, and 17 cm deep, made of wood, and covered with red felt. The four sides of the box (all but the top and bottom) were also covered with two layers of white lace; this lace “skirt” reached the apparatus floor and hid the mechanism that allowed the box to move back and forth across the apparatus.

The box moved along a slit 104 cm wide and 2 cm deep in the apparatus floor, located 28.5 cm from the left wall and 35 cm from the back wall. The box was mounted 0.5 cm above the apparatus floor on four small rubber wheels. Two metal plates anchored to the bottom of the box protruded through the slit in the apparatus floor and were attached beneath the floor to the top of a belt loop. At the start of each trial, the box was positioned at the left end of the slit. When the motorized system that drove the belt loop was activated, the top of the belt moved clockwise, carrying the box to the right at a constant speed of about 50 cm/s. After the box traveled for 75 cm (its leading edge was then 123 cm from the left wall), its metal plates hit a reverse-switch under the apparatus floor; this caused the top of the belt to now move counterclockwise, so that the box was carried back to its starting position. The box then stopped until the motorized system was activated once more. In the inert condition, the experimenter’s gloved hand activated the motorized system by hitting a microswitch located 0.25 cm to the left of the box and 1.25 cm behind the slit; the microswitch was 2.7 cm high, 0.2 cm wide, and 0.5 cm deep, and was covered with black contact paper. The hand simultaneously hit the microswitch and the box, so that it appeared as though the hand caused the box to move. In the self-propelled condition, the experimenter activated the motorized system by depressing a button on a control panel located under the apparatus floor. The box’s movement back and forth across the apparatus was accompanied by noise from the motorized system; this noise was identical in the inert and self-propelled conditions.

During the experiment, a wall partition filled the right end of the apparatus and was fastened in place with Velcro and stabilized with weights. The wall partition was made of foam board, was covered with the same grey granite-patterned contact paper as the back wall of the apparatus, and consisted of two joined surfaces: a side surface, which stood perpendicular to and abutted the back wall of the apparatus; and a front surface, which stood parallel to the back wall, 13 cm from the front edge of the apparatus. The side surface was 73.5 cm high and 65 cm deep. The front surface was also 73.5 cm high and could be folded so that its width (and hence the location of the side surface) varied across events. In the near-wall familiarization and test events, the front surface was 41 cm wide; in this event, the side surface stood 123 cm from the left wall of the apparatus, at the point where the box reversed direction (we will refer to this position of the wall partition as the near position). Although the box appeared to hit the side surface and “bounce back”, in actuality only its lace skirt contacted the side surface; the reverse-switch under the apparatus caused the box to reverse direction. In the far-wall familiarization and test events, the front surface was 21 cm wide, so that the side surface now stood 143 cm from the left wall, 20 cm to the right of the point where the box reversed direction (we will refer to this position of the wall partition as the far position).

The screen used during the familiarization trials was 50.5 cm high, 90 cm wide, and 0.5 cm thick; it was made of foam board, covered with green contact paper, and supported at the back by a wooden base. During the familiarization trials, the screen stood parallel to and 9 cm from the front edge of the apparatus, and abutted the right wall of the apparatus. The screen hid the right portion of the box’s trajectory as it moved back and forth across the apparatus. It also hid a large portion of the wall partition: only the top 23 cm of the wall partition, in its near or far position, was visible above the screen (see Fig. 1).

The infants were tested in a brightly lit testing room, and two 40-W fluorescent light bulbs attached to the front and back walls of the apparatus provided additional light. Two wooden frames, each 192 cm high, 63.5 cm wide, and covered with gray cloth, stood at an angle on either side of the apparatus; these frames served to isolate the infants from the testing room.

2.1.3. Events

In the following text, the numbers in parentheses indicate the number of seconds taken to perform the actions described. To help the experimenter adhere to the events’ scripts, a metronome beat softly once per second.

2.1.3.1. Inert condition

Near-wall familiarization event

At the start of the near-wall familiarization event, the wall partition was in its near position. The box was in its starting position at the left end of the slit; the experimenter’s gloved right hand rested palm down on the apparatus floor, 9 cm to the left of the box; and the screen was in place, 26 cm to the right of the box. The hand rotated 90 degrees while swinging back (so the palm now faced the box) (1 s) and then hit the box (and the microswitch, surreptitiously), to initiate the box’s motion (1 s). While the hand returned to its starting position, the box moved behind the screen, reversed direction, and emerged from behind the screen to return to its starting position (3 s). After a 1-s pause, the event was repeated. Each event cycle thus lasted about 6 s; cycles were repeated until the computer signaled the end of the trial (see below). When this occurred, a second experimenter lowered the curtain in front of the apparatus.

Far-wall familiarization event

The far-wall familiarization event was identical to the near-wall familiarization event except that the wall partition was in its far position.

Near-wall test event

The near-wall test event was similar to the near-wall familiarization event except that the screen was removed from the apparatus. Therefore, the infants could watch as the box traveled to the right, hit the wall partition, reversed direction (as though bouncing back), and returned to its starting position.

Far-wall test event

The far-wall test event was identical to the near-wall test event except that the wall partition was in its far position, so the box appeared to reverse direction spontaneously.3

2.1.3.2. Self-propelled condition

The events shown in the self-propelled condition were identical to those in the inert condition except that the experimenter’s hand remained palm down on the apparatus floor, 9 cm to the left of the box in its starting position, throughout the experiment. In each event cycle, after a 1-s pause, the experimenter used her left hand to press the button on the control panel (1 s), out of the infants’ view. The box then traveled through the apparatus and returned to its starting position (3 s), followed by a 1-s pause. Each event cycle thus lasted 6 s, as in the inert condition; in addition, the experimenter pressed the button at the point in each cycle where she would have hit the box, so that the timing of the box’s movement across the apparatus was similar across the two conditions.

2.1.4. Procedure

During the experiment, the infant sat on a parent’s lap in front of the apparatus, facing a point midway between (71.5 cm from) the left wall of the apparatus and the wall partition in its far position; the infant’s head was approximately 100 cm from the slit in the apparatus floor. Parents were instructed not to interact with their infant during the experiment; they were also asked to close their eyes during the test trials.

The infant’s looking behavior was monitored by two observers who watched the infant through peepholes in the cloth-covered frames on either side of the apparatus. The observers could not see the events from their viewpoints and they did not know the order in which the test events were presented. Each observer held a button box linked to a computer and pressed the button when the infant attended to the events. The looking times recorded by the primary observer were used to determine when a trial had ended (see below).

The infants first saw the near- and far-wall familiarization events appropriate for their condition (inert or self-propelled) on alternate trials for three pairs of trials. Half the infants in each condition saw the near-wall event first, and half saw the far-wall event first. Each familiarization trial ended when the infant either (1) looked away for 2 consecutive seconds after having looked at it for at least 5 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 2 consecutive seconds.

Next, the infants saw the near- and far-wall test events appropriate for their condition on alternate trials for two pairs of test trials. The events were presented in the same order as in the familiarization trials. Each test trial ended when the infant (1) looked away for 2 consecutive seconds after having looked for at least 5 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 2 consecutive seconds. The 5-s minimum value corresponded to approximately one event cycle and was chosen to ensure that the infant had sufficient opportunity to notice that the box reversed direction either spontaneously or after hitting the wall partition.4

To assess interobserver agreement during the familiarization and test trials, each trial was divided into 100-ms intervals, and the computer determined within each interval whether the two observers agreed on whether the infant was or was not looking at the event. Percent agreement was calculated for each trial by dividing the number of intervals in which the observers agreed by the total number of intervals in the trial. Interobserver agreement was measured for all 32 infants and averaged 94% per trial per infant.

Preliminary analysis of the infants’ looking times during the test trials revealed no significant interaction among condition, event, and order, F(1, 24) = 0.54, or among condition, event, and sex, F(1, 24) = 3.64, p > .068; the data were therefore collapsed across order and sex in subsequent analyses.5

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Familiarization trials

The infants’ looking times during the three pairs of familiarization trials were averaged and analyzed by means of a 2 × 2 ANOVA with condition (inert or self-propelled) as a between-subjects factor and event (far- or near-wall) as a within-subject factor. The main effects of condition, F(1, 30) = 0.00, and event, F(1, 30) = 0.42, were not significant, nor was the interaction between condition and event, F(1, 30) = 0.70, indicating that the infants in the two conditions did not differ reliably in their mean looking times at the far- and near-wall familiarization events (inert condition: far-wall event: M = 44.9, SD = 12.7; near-wall event: M = 45.2, SD = 13.0; self-propelled condition: far-wall event: M = 46.2, SD = 15.1; near-wall event: M = 43.8, SD = 17.6).

2.2.2. Test trials

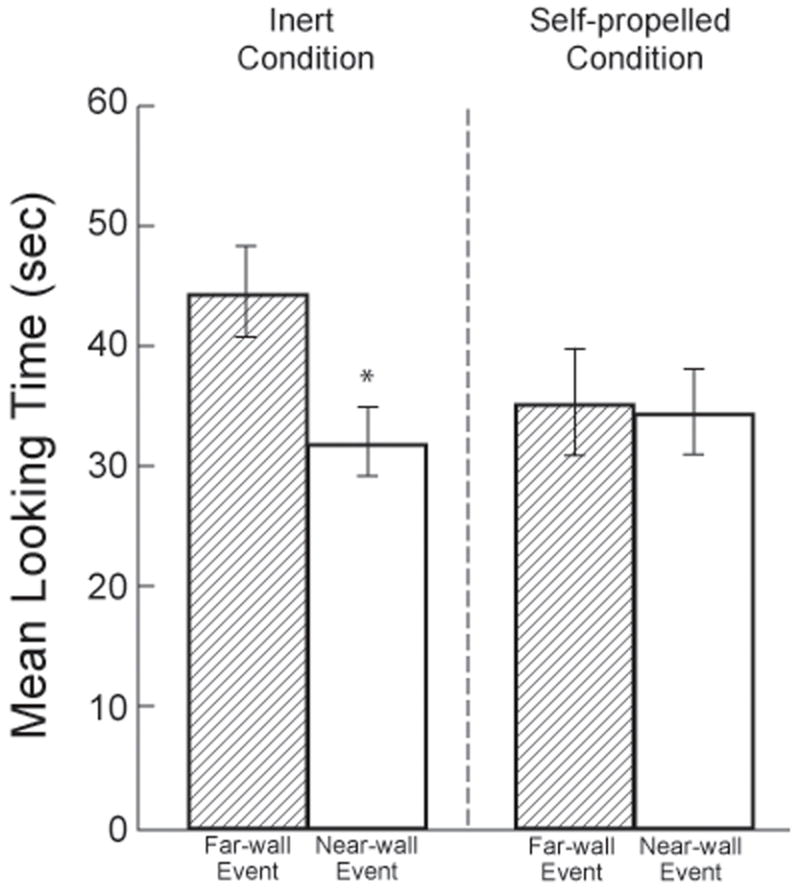

The infants’ looking times during the two pairs of test trials (see Fig. 2) were averaged and analyzed in the same manner as the familiarization data. The main effect of event, F(1, 30) = 9.35, p < .005, and the condition × event interaction, F(1, 30) = 7.23, p < .025, were significant, but the main effect of condition was not, F(1, 30) = 0.47. Planned comparisons revealed that the infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the far- (M = 44.5, SD = 15.3) than at the near-wall (M = 32.0, SD = 11.6) test event, F(1, 30) = 16.53, p < .0005, Cohen’s d = 1.3, whereas the infants in the self-propelled condition looked about equally at the two events (far-wall event: M = 35.3, SD = 17.9; near-wall event: M = 34.5, SD = 14.4), F(1, 30) = 0.07, d = 0.1. In addition, the infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the far-wall event than did those in the self-propelled condition, F(1, 30) = 8.85, p < .01, d = 0.6, whereas the infants in the inert and self-propelled conditions looked about equally at the near-wall event, F(1, 30) = 0.69, d = −0.2.

Figure 2.

Mean looking times of the infants in Experiment 1 during the test trials. Error bars represent standard errors. A star (*) indicates p < .05.

Examination of the individual infants’ mean looking times during the test trials indicated that, whereas 14 of the 16 infants in the inert condition looked longer at the far- than at the near-wall test event, Wilcoxon signed-ranks T = 8, p < .001, only 9 of the 16 infants in the self-propelled condition did so, T = 59, p > .20.

2.3. Discussion

The infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the far- than at the near-wall test event, whereas those in the self-propelled condition looked about equally, and equally short, at the two events. These results suggest that, during the familiarization trials, the infants in the inert condition categorized the box as inert. Since (1) the box began to move only when hit by the hand and (2) it was unclear what caused it to reverse direction behind the screen, the infants had no unambiguous evidence that the box was anything other than inert, and they categorized it as such. During the test trials, the infants expected the box, once in motion, to follow a smooth path, with no abrupt changes in direction, unless acted upon by an external force.6 As a result, they were surprised in the far-wall event when the box reversed direction spontaneously, but they were not surprised in the near-wall event when it reversed direction after hitting the wall partition.

In contrast, the infants in the self-propelled condition categorized the box as self-propelled during the familiarization trials, since it initiated its own motion in plain view. During the test trials, the infants recognized that the box could alter its trajectory spontaneously—by applying its internal energy—or as a result of external impact. Thus, the infants found neither the far- nor the near-wall test event surprising, and they tended to look equally, and equally short, at the two events.

The results of Experiment 1 thus suggest that, by 5 months of age, infants (1) endow self-propelled but not inert objects with internal energy (e.g., Gelman, 1990; Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995); (2) expect an object to follow a smooth path unless a force, either internal or external, intervenes to change it; and hence (3) are surprised when an inert but not a self-propelled object abruptly deviates from its initial path without external impact.

2.3.1. Links to prior findings

The results of Experiment 1 also have implications for a number of prior findings. First, the results of the inert condition support the speculation, put forth earlier, that the infants tested by Spelke et al. (1994) failed to detect the path violation they were shown because it was too subtle for them to detect. The infants in the present experiment were presented with a full reversal in plain view, and they had no difficulty detecting this violation.

Second, and relatedly, the results of the inert condition help reconcile previously discrepant findings in the infancy literature. In contrast to the violation-of-expectation findings of Spelke et al. (1994), experiments using action tasks such as predictive reaching (for visible objects) and predictive tracking (for occluded objects) have found that young infants do expect objects to follow a smooth path, with no abrupt change in direction (e.g., Kochukhova & Gredebäck, 2007; Spelke & von Hofsten, 2001; von Hofsten et al., 1998, 2007). These contrastive results have sometimes been taken to point to a possible dissociation between the physical knowledge underlying infants’ responses in violation-of-expectation and action tasks (e.g., von Hofsten et al., 1998). However, the positive results of the inert condition in Experiment 1 suggest that young infants can demonstrate an expectation that objects follow a smooth path in violation-of-expectation as well as in action tasks.

To give an example of such an action task, Kochukhova and Gredebäck (2007) showed 6-month-old infants computer-animated events in which a self-propelled object approached and then disappeared behind an occluder; while behind the occluder, the object effected a 90-degree turn (e.g., the object disappeared behind the left edge of the occluder and reappeared at its bottom edge). Analyses of the infants’ anticipatory responses using an eye-tracker revealed that, on the initial trials, the infants expected the object to reappear further along its pre-occlusion trajectory, on the opposite side of the occluder (e.g., at the occluder’s right edge). After two or three trials, however, the infants began to anticipate the object’s reappearance on the correct side of the occluder (e.g., at the occluder’s bottom edge). One interpretation of these results is that when watching a self-propelled object move behind an occluder, young infants initially hold the default assumption that the object will follow a smooth path, with no abrupt change in direction, just as they do for an inert object. However, if this expectation is violated, infants conclude that the object is using its internal energy to alter its trajectory when behind the occluder, and they then allow their prior observations (about where the object has reappeared on previous trials) to guide their future anticipations.

Finally, the results of the self-propelled condition in Experiment 1 are consistent with a plethora of experiments over the past 20 years that have presented young infants with a self-propelled object moving back and forth across an apparatus, with or without occluders at the center of the apparatus (e.g., Aguiar & Baillargeon, 1999, 2002; Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Baillargeon & Graber, 1987; Bremner et al., 2005; S. P. Johnson, 2004; S. P. Johnson, Amso, & Slemmer, 2003; Kellman & Spelke, 1983; Luo & Baillargeon, 2005a, 2005b; Slater, Johnson, Brown, & Badenoch, 1996; Spelke et al., 1995a; Wilcox, 1999; Wilcox & Baillargeon, 1998; Wilcox & Schweinle, 2003). Though this issue was typically not examined directly, there was no empirical reason to suspect that the infants in these experiments were surprised when the object reversed direction at either end of its trajectory, and the present data support this interpretation.

3. Experiment 2: Can an inert or a self-propelled object pass through an obstacle?

The results of Experiment 1 suggested that 5-month-old infants are surprised when an inert but not a self-propelled object spontaneously reverses direction. However, an alternative interpretation of the results was that the infants were confused by the self-propelled box and hence held no specific expectation about its behavior, resulting in equal looking times at the near- and far-wall test events.

This alternative interpretation was unlikely: as was mentioned in the last section, numerous experiments over the past 20 years have presented infants with events involving self-propelled objects; had infants found these objects confusing, the results of the experiments would have been consistently negative, and they were not. Nevertheless, Experiment 2 was conducted to definitively rule out this alternative interpretation.

A large body of evidence suggests that young infants interpret physical events in accord with a principle of persistence (e.g., Baillargeon, 2008; Baillargeon et al., in press-a), which states that objects persist as they are through time and space. An important corollary of this principle is the solidity principle, which states that, for two objects to each persist in time and space, the two cannot occupy the same space at the same time (e.g., Spelke, 1994; Spelke et al., 1995b). Numerous investigations have shown that infants aged 2.5 months and older recognize that an object, whether self-propelled or not, cannot pass through space occupied by another object (e.g., Aguiar & Baillargeon, 1998, 2003; Baillargeon, 1986, 1987, 1991; Baillargeon et al., 1985; Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Baillargeon, Graber, DeVos, & Black, 1990; Hespos & Baillargeon, 2001b; Luo et al., 2003; Saxe, Tzelnic, & Carey, 2006; Sitskoorn & Smitsman, 1995; Spelke et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2004, 2005). Experiment 2 therefore examined whether 5-month-old infants would recognize that an object, whether self-propelled or not, cannot pass through another object.

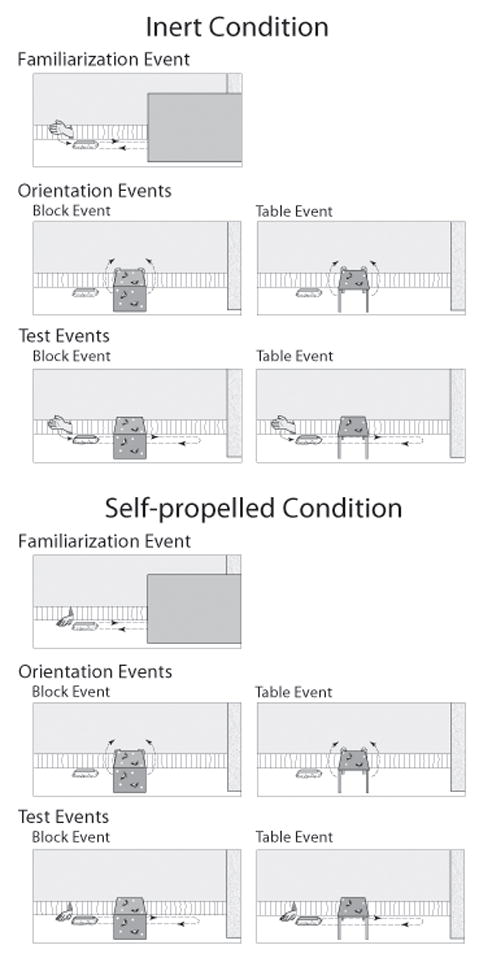

The infants were assigned to an inert or a self-propelled condition (see Fig. 3). The infants in the self-propelled condition first received familiarization trials identical to those in Experiment 1 except that—in these trials as in all other trials in Experiment 2—the wall partition was always in the far position. Next, the infants received two orientation trials in which they were introduced to a large table and a large block. Finally, the infants were shown a table and a block test event. At the start of the table event, the table rested across the box’s path on the apparatus floor, directly in front of the infants; the box began to move to the right, passed under the table, reversed direction, passed under the table once more, and finally returned to its starting position. The block event was similar except that the table was replaced with the block; the box appeared to pass through the block once as it traveled to the right and once more after it reversed direction to return to its starting position. The infants in the inert condition saw the same familiarization, orientation, and test events, except that the box did not initiate its own motion: as in the inert condition of Experiment 1, the box began to move only after it was hit by the experimenter’s gloved hand.

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing of the familiarization, orientation, and test events in Experiment 2

We reasoned that if the infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 1 looked about equally at the test events because they were confused by our self-propelled box, then the infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 2 should also be confused and hence should also look about equally at the test events. However, if the infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 1 looked about equally at the test events because they realized that the box could reverse its motion either spontaneously or following its impact with the wall partition, then the infants in Experiment 2 should respond differentially to the block and table test events. Because by 5 months infants realize that an object, whether self-propelled or not, cannot pass through another object (e.g., Baillargeon, 1987, 1991; Baillargeon et al., 1985, 1990; Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Hespos & Baillargeon, 2001b; Luo et al., 2003; Saxe et al., 2006; Spelke et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2004, 2005), the infants should be surprised when the box appeared to pass through the block but not under the table. The infants should thus look reliably longer at the block than at the table event.

In contrast to the infants in the self-propelled condition, those in the inert condition should find both test events surprising: the table event, because the box appeared to reverse direction spontaneously (as in the far-wall test event of Experiment 1); and the block event, because the box appeared to reverse direction spontaneously and to pass through the block. The infants should tend to look equally, and equally long, at the block and table events.7

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

Participants were 32 healthy term infants, 16 male and 16 female, ranging in age from 4 months, 16 days to 5 months, 9 days (M = 5 months, 1 day, SD = 6.4 days). Another 8 infants were tested but eliminated, 6 because they looked for the maximum amount of time allowed (60 s) on all four test trials, 1 because of drowsiness, and 1 because of observer difficulties. Half the infants were randomly assigned to the inert condition (8 male and 8 female; M = 5 months, 1 day, SD = 6.5 days), and half to the self-propelled condition (M = 5 months, 0 day, SD = 6.5 days).

3.1.2. Apparatus

The apparatus and stimuli used in Experiment 2 were identical to those in Experiment 1 except as noted here. The wall partition remained in the far position throughout Experiment 2. The table used in the table orientation and test events was 17 cm high, 22 cm wide, and 69 cm deep. The top of the table was made of cardboard, was 0.3 cm thick, was covered on both sides with a blue contact paper decorated with red and white sailboat stickers and small yellow dots, and rested on four thin legs, one in each corner. Each table leg consisted of a wooden rod, 16.7 cm high and 0.7 cm in diameter, and painted blue. A different block was used in the block orientation and test events. The orientation block was made of cardboard, was 17 cm high, 22 cm wide, and 69 cm deep, and was covered with the same contact paper as the table. The test block was identical except that a tunnel was cut through it, to allow the box to pass through. The opening of the tunnel on either side of the box was 6.5 cm high and 21 cm wide; the opening was located 22.5 cm from the front of the block. Because the infants sat centered in front of the block, they could not see the opening of the tunnel on either side of the block. During the table and block orientation events, the experimenter wore yellow rubber gloves and introduced both hands into the apparatus through the grey fringe at the bottom of the back wall.

3.1.3. Events

3.1.3.1. Inert condition

Familiarization event

The familiarization event shown in the inert condition of Experiment 2 was identical to the far-wall familiarization event shown in the inert condition of Experiment 1.

Table orientation event

Prior to the orientation events, the screen used in the familiarization trials was removed. At the beginning of the table orientation event, the box rested in its starting position at the left end of the slit; the table stood on the apparatus floor against the back wall, 12.5 cm to the right of the box, directly in front of the infants; and the experimenter’s gloved hands grasped the left and right sides of the table. To start, the hands rotated the table 90 degrees upward (3 s) until it stood against the back of the apparatus, with its inside top surface facing the infant. After a 2-s pause, the hands returned the table to its original position on the apparatus floor (3 s) and then paused for another 2 s. Each event cycle thus lasted approximately 10 s. Cycles were repeated until the computer signaled that the trial had ended.

Block orientation event

The block orientation event was identical to the table orientation event except that the table was replaced with the (closed) orientation block.

Table test event

The table test event was identical to the familiarization event except that the screen was absent and the table was in place. After the box was hit by the experimenter’s gloved hand, it moved to the right, passed under the table, reversed direction, passed under the table once more, and finally returned to its starting position. Because the table was 69 cm deep and stood on four thin legs, there was visibly ample room for the box to pass through.

Block test event

The block test event was identical to the table test event except that the table was replaced with the test block; the tunnel in the block lay centered over the box’s path, allowing the box to move back and forth across the apparatus. After the box was hit by the experimenter’s gloved hand, it moved to the right, passed through the block, reversed direction, and finally passed through the block once more as it returned to its starting position.

3.1.3.2. Self-propelled condition

The events shown in the self-propelled condition were similar to those in the inert condition except that during the familiarization and test trials the experimenter’s gloved right hand remained stationary on the apparatus floor, 9 cm to the left of the box in its starting position. As in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 1, the experimenter depressed a button on the control panel under the apparatus to set the box into motion.

3.1.4. Procedure

The procedure used in Experiment 2 was similar to that in Experiment 1 except that the infants received two orientation trials between the familiarization and test trials. Half the infants in each condition saw the table orientation and test events first, and half saw the block orientation and test events first. Each orientation trial ended when the infant (1) looked away for 2 consecutive seconds after having looked for at least 10 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 2 consecutive seconds. The 10-s minimum value corresponded to one event cycle and was chosen to give the infant ample exposure to the table or block. During the orientation trials, the primary observer was absent so that he or she could not guess from available noise cues whether the table or block was introduced first (because the table was lighter than the block, it made less noise when lowered onto the apparatus floor). Therefore, the infant’s looking behavior during the orientation trials was monitored only by the secondary observer. Interobserver agreement during the familiarization and test trials was measured for 31 of the 32 infants and averaged 95% per trial per infant.

Preliminary analysis of the infants’ looking times during the test trials revealed no significant interaction among condition, event, and order, F(1, 24) = 1.20, p > .28, or among condition, event, and sex, F(1, 24) = 0.38; the data were therefore collapsed across order and sex in subsequent analyses.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Familiarization trials

The infants’ looking times during the six familiarization trials were averaged and analyzed as in Experiment 1. The analysis yielded a significant effect of condition, F(1, 30) = 9.13, p < .01, indicating that the infants in the inert condition (M = 47.6, SD = 7.0) looked reliably longer during the familiarization trials than did those in the self-propelled condition (M = 35.5, SD = 14.5).

Examination of the familiarization data in Experiments 1 and 2 makes clear that, whereas the infants in the inert condition looked about as long in the two experiments, those in the self-propelled condition looked less in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1. Why this was the case is unclear, as the infants in the self-propelled condition of the two experiments saw essentially the same familiarization event (the only difference was that in Experiment 1 the wall partition was placed in the near and far positions on alternate trials). Since the infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 2 responded as expected in subsequent trials, and since this is the only experiment where a difference was found in the responses of the infants in the inert and self-propelled conditions during the familiarization trials, we attribute this difference to sampling variation.

3.2.2. Orientation trials

The infants’ looking times during the two orientation trials were analyzed by means of a 2 × 2 ANOVA with condition (inert or self-propelled) as a between-subjects factor and with event (block or table) as a within-subject factor. The main effects of condition, F(1, 30) = 0.76, and event, F(1, 30) = 0.82, were not significant, nor was the condition × event interaction, F(1, 30) = 0.21, indicating that the infants in the two conditions did not differ reliably in their looking times at the block and table orientation events (inert condition: block event: M = 54.2, SD = 12.9; table event: M = 52.5, SD = 15.5; self-propelled condition: block event: M = 52.3, SD = 16.0; table event: M = 47.2, SD = 18.2).

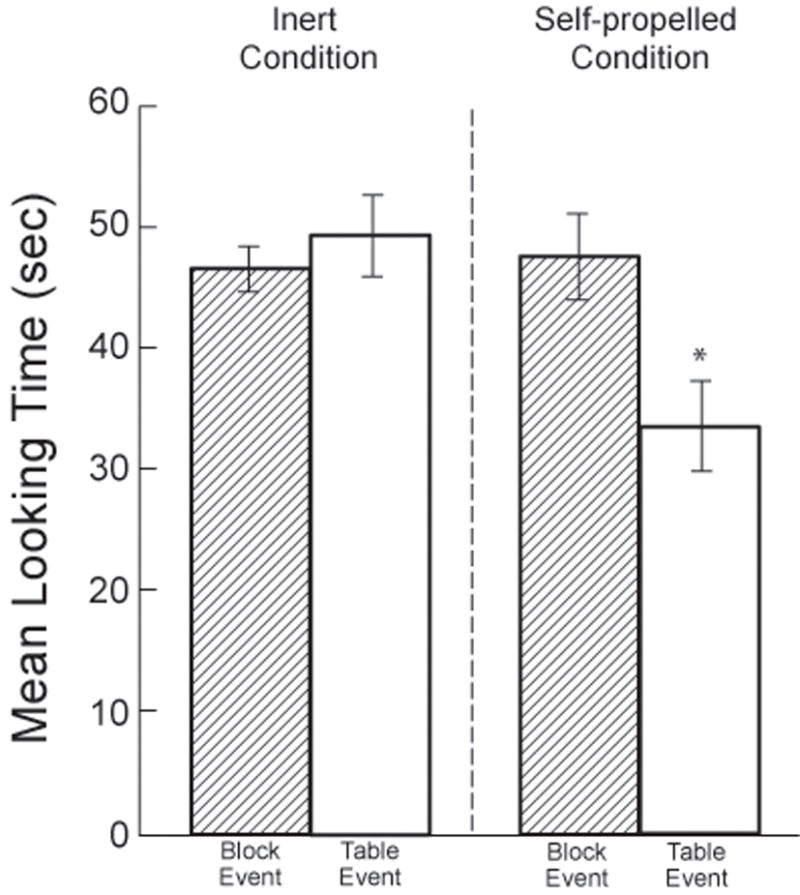

3.2.3. Test trials

The infants’ looking times during the two pairs of test trials (see Fig. 4) were averaged and analyzed in the same manner as the orientation trials. The analysis yielded a marginally significant main effect of condition, F(1, 30) = 3.63, p < .07, a significant main effect of event, F(1, 30) = 5.58, p < .025, and a significant condition × event interaction, F(1, 30) = 12.21, p < .0025. Planned comparisons indicated that the infants in the inert condition looked about equally at the block (M = 46.8, SD = 7.4) and table (M = 49.6, SD = 13.5) events, F(1, 30) = 0.64, d = −0.2, whereas those in the self-propelled condition looked reliably longer at the block (M = 47.8, SD = 14.5) than at the table (M = 33.7, SD = 15.2) event, F(1, 30) = 17.15, p < .0005, d = 1.4. In addition, although the infants in the inert and self-propelled conditions looked about equally at the block event, F(1, 30) = 0.07, d = −0.1, the infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the table event than did those in the self-propelled condition, F(1, 30) = 21.78, p < .0001, d = 1.1.

Figure 4.

Mean looking times of the infants in Experiment 2 during the test trials. Error bars represent standard errors. A star (*) indicates p < .05.

Examination of the individual infants’ mean looking times indicated that, whereas 14 of the 16 infants in the self-propelled condition looked longer at the block than at the table event, T = 6, p < .0005, only 5 of the 16 infants in the inert condition did so, T = 53, p > .20.8

3.3. Discussion

During the test trials, the infants in the self-propelled condition looked reliably longer at the block than at the table event, whereas the infants in the inert condition looked about equally, and equally long, at the two events. These results suggest that the infants in self-propelled condition (1) categorized the box as self-propelled during the familiarization trials, since it initiated its own motion in plain sight; (2) realized that the box could not only initiate but also alter its motion; (3) understood that the box could pass under the table but not through the block; and hence (4) were surprised in the block event when the box appeared to pass through the block. These results cast doubt on the suggestion that the infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 1 looked about equally at the test events because they were confused by the self-propelled box and hence held no expectation about its behavior. The infants in the self-propelled condition of Experiment 2 saw the same self-propelled box and clearly had an expectation that it could not pass through the block.

The results of Experiment 2 also suggest that the infants in the inert condition (1) categorized the box as inert, since they were given no evidence to the contrary; (2) expected the box, once set into motion by the hand, to follow a smooth path; (3) realized that the box could pass under the table but not through the block; and hence (4) found both test events surprising: the table event, because the box spontaneously reversed its trajectory, and the block event, because the box not only reversed its trajectory but also appeared to pass through the block.

Together, the results of the inert and self-propelled conditions in Experiment 2 confirm those of Experiment 1: they provide additional evidence that 5-month-old infants are surprised when an inert but not a self-propelled object spontaneously reverses direction. In addition, the results confirm prior evidence that young infants interpret physical events in accord with a solidity principle and realize that two objects, whether inert or self-propelled, cannot occupy the same space at the same time (e.g., Baillargeon, 1987; Hespos & Baillargeon, 2001b; Luo et al., 2003; Saxe et al., 2006; Spelke et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2004).

More generally, the results of Experiments 1 and 2 support the hypothesis that infants endow self-propelled objects with an internal source of energy (e.g., Gelman, 1990; Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995). By 5 months of age, infants are not surprised when a self-propelled object spontaneously reverses its motion, because they realize that the object can use its internal energy to do so. However, they are surprised when a self-propelled object appears to pass though an obstacle, because they understand that no application of internal energy could enable the object to occupy the same space as the obstacle.

4. Experiment 3: Can an inert or a self-propelled object remain stationary when hit or pulled?

We have seen that young infants appreciate that a self-propelled object can use its internal energy to reverse its motion. In Experiment 3, we asked whether young infants also believe that a self-propelled object can use its internal energy to resist efforts to move it and hence to remain stationary when hit or pulled.

The point of departure for this experiment came from investigations of infants’ responses to collision events. Prior research with inert objects (e.g., Baillargeon, 1995; Kotovsky & Baillargeon, 1998, 2000; Wang, Kaufman, & Baillargeon, 2003) suggests that, when a first object hits a second object, infants as young as 2.5 months of age expect the second object to be displaced and are surprised if it is not. By 5.5 to 6.5 months of age, infants begin to take into account the size (or weight) of the first object, and they now expect the second object to be displaced farther when hit by a larger as opposed to a smaller object. Finally, by about 9 months of age, infants begin to take into account the size (or weight) of the second object, and they now expect a very large object to remain stationary when hit by a small object. Prior research with self-propelled objects (e.g., Leslie, 1982, 1984b; Leslie & Keeble, 1987; Oakes, 1994), however, paints a different picture: in particular, it suggests that young infants may not expect a self-propelled object to be displaced when hit.

In a seminal experiment, Leslie and Keeble (1987) habituated 6-month-old infants to one of two filmed events; both events involved two self-propelled objects, a red and a green brick.9 In one event (launching event), one brick began to move toward the other brick and collided with it; the second brick then immediately moved off. In the other event (delayed-reaction event), the second brick moved off only after a 0.5-s delay. During test, the infants watched the same event they had seen during habituation, now shown in reverse. The results of the test trials indicated that the infants habituated to the launching event showed greater recovery of attention than those habituated to the delayed-reaction event. This finding suggested that the infants attributed a causal role to the first brick only in the launching event: they assumed that the first brick caused the second one to move in the habituation trials, and they looked reliably longer when the bricks’ causal roles were reversed in the test trials.

From the present perspective, the results of the habituation trials were just as interesting: the infants tended to look equally whether they were shown the launching or the delayed-reaction event (see also Leslie, 1982, 1984b; Oakes, 1994). This finding suggested that the infants were not surprised that the second brick did not move off immediately when hit, because they understood that the second brick could use its internal energy to counteract the impact from the first brick. As such, this finding gave rise to the possibility that infants might not be surprised if a self-propelled object did not move off at all when hit. Experiment 3 was designed to test this possibility: it asked whether 6-month-old infants would be surprised if an inert but not a self-propelled object remained stationary when hit.

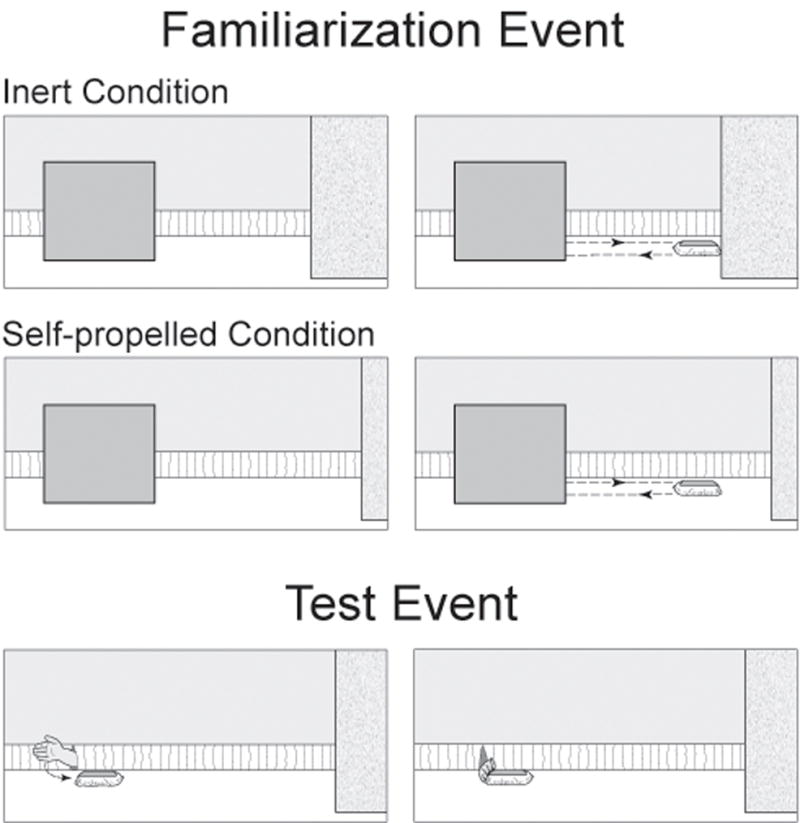

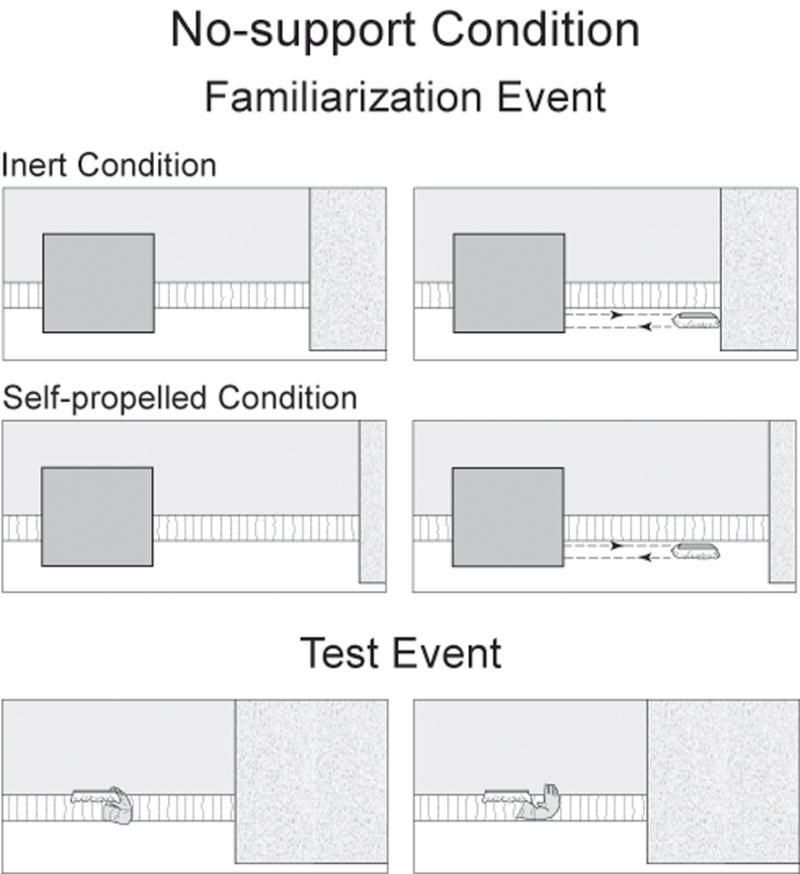

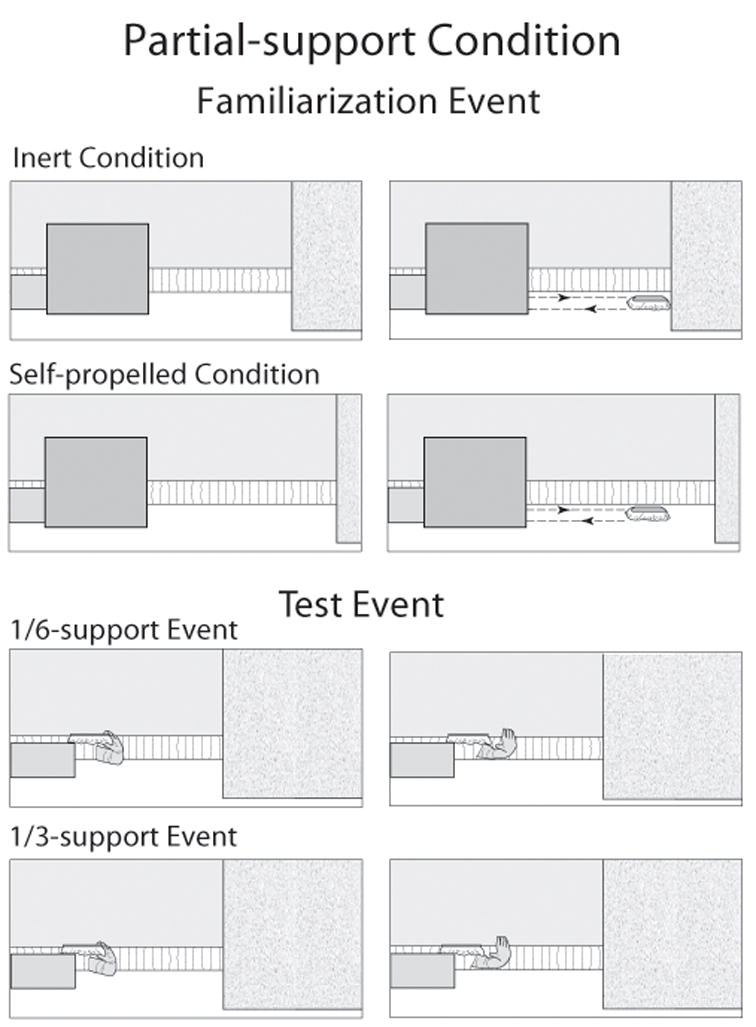

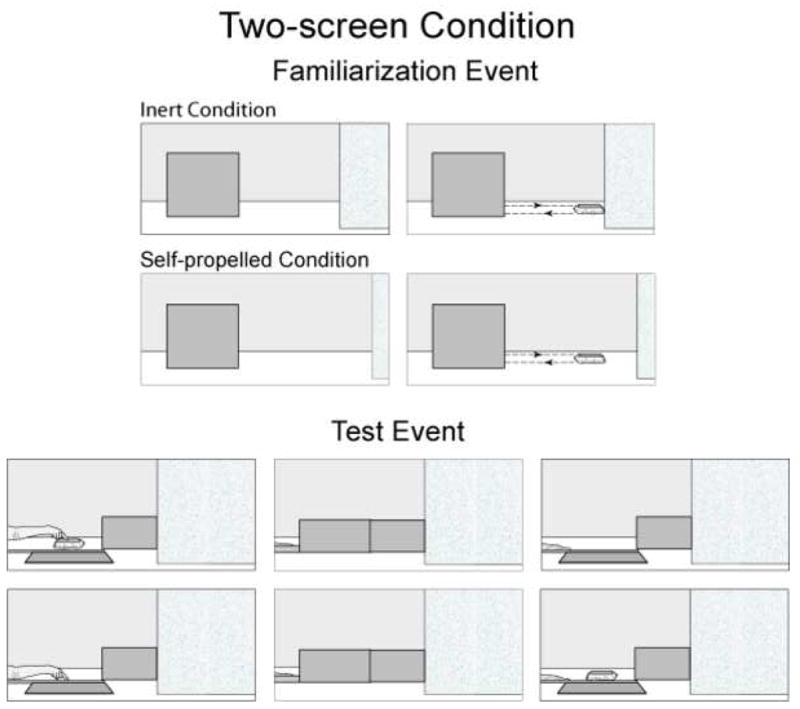

The infants were assigned to an inert or a self-propelled condition and saw familiarization and test events involving the same box as in the previous experiments (see Fig. 5). All of the infants saw the same test event, on two successive trials: the experimenter’s gloved hand hit the box, which remained stationary. As before, the infants received familiarization trials prior to the test trials that made clear whether the box was inert or self-propelled. Given the nature of the test event, however, we could no longer use the same familiarization events as in the preceding experiments. Accordingly, we designed new familiarization events that built on the results of Experiments 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

Schematic drawing of the familiarization and test events in Experiment 3

At the start of the familiarization event shown in the self-propelled condition, the wall partition was in its far position, and the box rested in its usual starting position at the left end of the slit; however, the box was now hidden by a large screen. During the event, the box emerged to the right of the screen, traveled to the right a short distance, reversed direction on its own (at its usual reversal point), and returned behind the screen. The familiarization event shown in the inert condition was similar except that the wall partition was in its near position: the box thus hit the wall partition before reversing direction and returning behind the screen. The familiarization event in the self-propelled condition thus presented the infants with unambiguous evidence that the box was self-propelled, since it reversed direction spontaneously. In contrast, the familiarization event shown in the inert condition presented the infants with no such evidence, since (1) it was unclear what caused the box to emerge from behind the screen, and (2) the box reversed direction as a result of external impact, after hitting the wall partition; on the default assumption that an object is inert until proven otherwise, the infants should categorize the box as inert.

In line with previous research (e.g., Baillargeon, 1995; Kotovsky & Baillargeon, 2000; Wang, et al., 2003), we predicted that, when shown the test event, the infants in the inert condition would expect the box to move when hit and would be surprised that it did not. But how would the infants in the self-propelled condition respond? We reasoned that if the infants endowed the self-propelled box with an internal source of energy (e.g., Gelman, 1990; Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995), they might consider it possible for the box to use its internal energy to counteract the hand’s impact. The infants might thus show little or no surprise that the box failed to move when hit, because they could readily generate an explanation for this outcome. We thus predicted that the infants in the inert condition would look reliably longer during the test trials than those in the self-propelled condition.

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

Participants were 16 healthy term infants, 8 male and 8 female, ranging in age from 5 months, 20 days to 6 months, 21 days (M = 6 months, 0 day, SD = 10.7 days). Another 2 infants were tested but eliminated, 1 because of fussiness and 1 because he looked for the maximum amount of time allowed (60 s) on both test trials. Half the infants were randomly assigned to the inert condition (4 male and 4 female; M = 6 months, 1 day, SD = 12.0 days), and half to the self-propelled condition (M = 6 months, 0 day, SD = 10.2 days).

4.1.2. Apparatus

The apparatus and stimuli used in Experiment 3 were identical to those in Experiment 1 except that a different screen was used during the familiarization trials. This screen was 39.5 cm high, 44.5 cm wide, and 0.5 cm thick, was covered with green contact paper, and was supported at the back by a metal base. During the familiarization trials, the screen stood centered in front of the box in its starting position, 16 cm from the left wall and 18 cm from the front edge of the apparatus. During the familiarization trials, the wall partition was in the near position in the inert condition and in the far position in the self-propelled condition. During the test trials, the wall partition was in a new position, midway between the near and far positions, 133 cm from the left wall (we will refer to this position of the wall partition as the midway position); the front surface of the wall partition was then 31 cm wide.

4.1.3. Events

4.1.3.1. Inert condition

Familiarization event

At the start of the familiarization event, the wall partition was in its near position, and the box rested in its starting position at the left end of the slit, hidden behind the screen. After a 1-s pause, the experimenter pressed the button on the control panel beneath the apparatus to initiate the box’s motion (1 s). The box then emerged to the right of the familiarization screen, traveled to the right a short distance, hit the wall partition, reversed direction (as though bouncing back), and returned to its starting position behind the screen (3 s). After a 1-s pause, the event was repeated. Each event cycle thus lasted about 6 s; cycles were repeated until the computer signaled the end of the trial (see below).

Test event

During the test event, the wall partition was in the midway position. The box rested at the left end of the slit, in its starting position, and the screen was removed from the apparatus. The motorized system was disabled and the box was anchored under the apparatus so that it could not move. At the start of the event, the experimenter’s right hand (in the same golden spandex glove as in Experiment 1) rested palm down on the apparatus floor, 9 cm to the left of the box. The hand rotated 90 degrees (so the palm now faced the box) while swinging back (1 s), and hit the box (1 s), which remained stationary. After hitting the box, the hand rested on the apparatus floor with its palm facing the box, 4.5 cm from the left edge of the box (2 s). The hand then returned to its starting position (1 s). After a 1-s pause, the event was repeated. Each event cycle thus lasted about 6 s; cycles were repeated until the computer signaled the end of the trial.

4.1.3.2. Self-propelled condition

The familiarization and test events shown in the self-propelled condition were identical to those in the inert condition except that in the familiarization event the wall partition was placed in the far position. The box thus appeared to reverse direction spontaneously, without hitting the wall partition.

4.1.4. Procedure

The infants first saw the familiarization event appropriate for their condition (inert or self-propelled) on six successive trials. Each trial ended when the infant (1) looked away for 2 consecutive seconds after having looked at it for at least 6 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 2 consecutive seconds. The 6-s minimum value corresponded to one event cycle and was chosen to ensure that the infant had the opportunity to see the box’s reversal. Next, all of the infants saw the test event for two successive trials. Each trial ended when the infant (1) looked away for 1 consecutive second after having looked for at least 18 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 1 consecutive second. The 18-s minimum value corresponded to three event cycles and was chosen to give the infants ample opportunity to observe that the box remained stationary after being hit (i.e., the infants could see that the hand had not accidentally missed the box—it hit the box squarely and yet the box did not move). Interobserver agreement during the familiarization and test trials was calculated for all 16 infants and averaged 92% per trial per infant.

Preliminary analysis of the infants’ looking times during the test trials revealed no significant interaction between condition and sex, F(1, 12) = 0.55; the data were therefore collapsed across sex in subsequent analyses.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Familiarization trials

The infants’ looking times during the six familiarization trials were averaged and analyzed by means of a single-factor ANOVA with condition (inert or self-propelled) as a between-subjects factor. The main effect of condition was not significant, F(1, 14) = 0.01, indicating that the infants in the two conditions did not differ reliably in their mean looking times during the familiarization trials (inert condition: M = 35.6, SD = 9.7; self-propelled condition: M = 35.1, SD = 9.3).

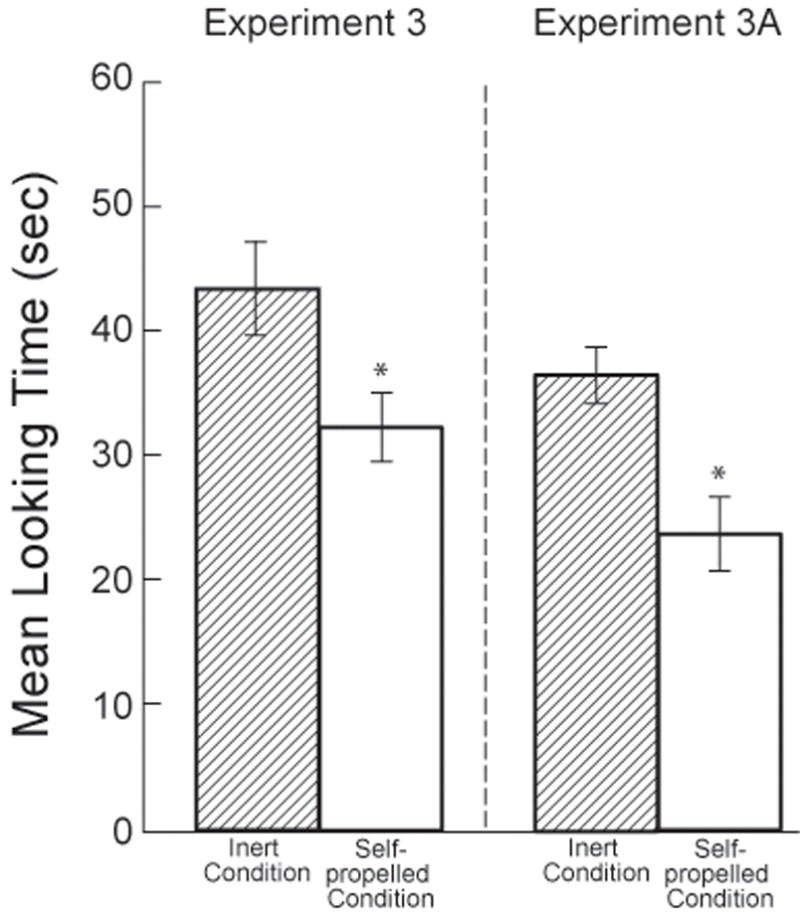

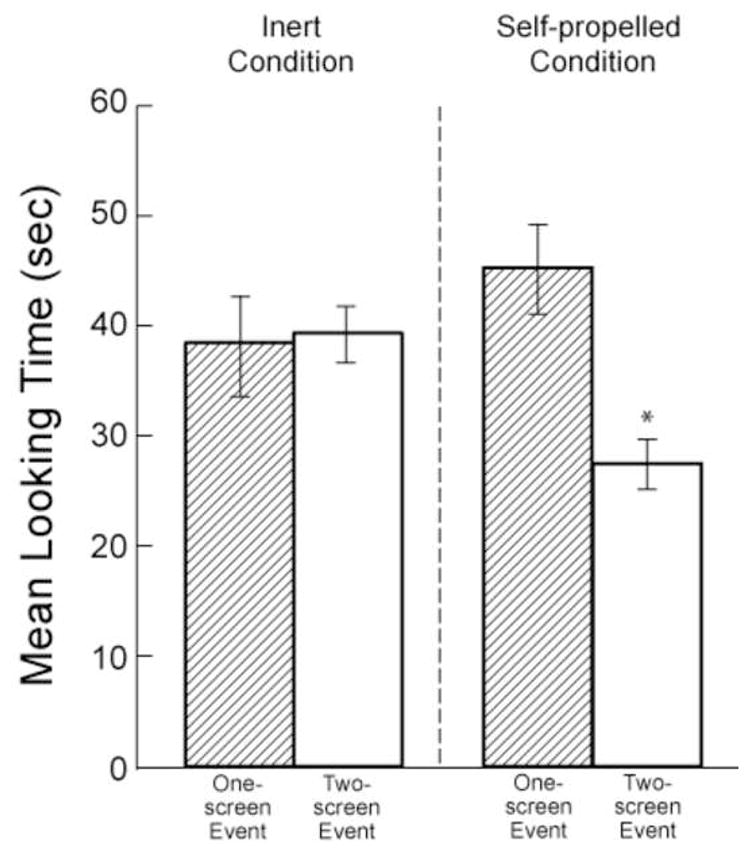

4.2.2. Test trials

The infants’ looking times during the two test trials (see Fig. 6) were averaged and analyzed in the same manner as the familiarization data. The main effect of condition was significant, F(1, 14) = 5.53, p < .05, d = 1.2, indicating that the infants in the inert condition (M = 43.5, SD = 10.7) looked reliably longer than did those in the self-propelled condition (M = 32.4, SD = 8.0) during the test trials. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test confirmed this result, W = 48, p < .05.

Figure 6.

Mean looking times of the infants in Experiments 3 and 3A during the test trials. Error bars represent standard errors. A star (*) indicates p < .05.

4.2.3. Further Results: Experiment 3A

The results of Experiment 3 suggested that (1) during the familiarization trials, the infants categorized the box as self-propelled when it reversed direction spontaneously and as inert when it did not, and (2) during the test trials, the infants were surprised when the inert but not the self-propelled box remained stationary when hit. These results suggested that the infants in the self-propelled condition endowed the box with a source of internal energy, and inferred that the box used its internal energy to counteract the hand’s impact.

To provide converging evidence for these results, additional 6-month-old infants were tested using a similar procedure except that, instead of hitting the box in the test event, the hand pulled on a strap attached to the left side of the box. As in Experiment 3, the box remained stationary when acted upon.

Participants were 16 healthy term infants, 7 male and 9 female, ranging in age from 5 months, 20 days to 6 months, 15 days (M = 6 months, 4 days, SD = 6.5 days). Another 5 infants were tested but eliminated, 4 because the infants looked for the maximum amount of time allowed (60 s) on both test trials, and 1 because of fussiness. Half the infants were randomly assigned to the inert condition (3 male and 5 female; M = 6 months, 3 days, SD = 5.1 days), and half to the self-propelled condition (M = 6 months, 5 days, SD = 7.9 days).

The apparatus, stimuli, events, and procedure used in Experiment 3A were similar to those in Experiment 3, with the following exceptions. The strap attached to the left side of the box consisted of two white cotton braids joined at the end with red tape; each braid was 13 cm long and 1 cm in diameter. During the familiarization trials, the strap brushed noiselessly against the apparatus floor as the box moved back and forth across the apparatus. At the start of the event shown in the test trials, the experimenter’s gloved hand held the strap folded against the box’s left side. After a 1-s pause, the hand stretched the strap to its full length at an upward angle (1 s), in an apparent effort to pull the box to the left, and maintained this position for 1 s. Next, the hand again folded the strap against the left side of the box (1 s). Each event cycle thus lasted about 4 s. Because each cycle was shorter than in Experiment 3 (4 instead of 6 s), each test trial ended when the infant (1) looked away for 1 consecutive second after having looked for at least 12 cumulative seconds, or (2) looked for 60 cumulative seconds without looking away for 1 consecutive second. The 12-s minimum value corresponded to three event cycles and was chosen to give the infants ample opportunity to observe that the box remained stationary when pulled. Interobserver agreement during the familiarization and test trials was measured for all 16 infants and averaged 91% per trial per infant. Preliminary analysis of infants’ looking times during the test trials revealed no significant interaction between condition and sex, F(1, 12) = 0.00; the data were therefore collapsed across sex in subsequent analyses.

The infants’ looking times during the six familiarization trials were averaged and analyzed as in Experiment 3. The main effect of condition was not significant, F(1, 14) = 1.80, p > .20, indicating that the infants in the two conditions did not differ reliably in their mean looking times during the familiarization trials (inert condition: M = 32.7, SD = 5.6; self-propelled condition: M = 39.9, SD = 14.1). The infants’ looking times during the two test trials (see Fig. 6) were averaged and analyzed as in Experiment 3. The main effect of condition was significant, F(1, 14) = 11.56, p < .005, d = 1.7, indicating that the infants in the inert condition (M = 36.7, SD = 6.5) looked reliably longer than those in the self-propelled condition (M = 23.8, SD = 8.5). A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test confirmed this result (W = 44, p < .025).

4.3. Discussion

In both Experiments 3 and 3A, the infants in the inert condition looked reliably longer at the test event than did those in the self-propelled condition. These data support three conclusions. First, in each experiment, the infants categorized the box as self-propelled when it reversed direction on its own and as inert when it reversed direction only after hitting the wall partition. These results confirm those of Experiments 1 and 2—a self-propelled object can reverse direction spontaneously—and also suggest that infants can use multiple cues to categorize objects as self-propelled: an object is viewed as self-propelled if it begins to move or reverses direction on its own.

Second, the results of Experiments 3 and 3A suggest that 6-month-old infants expect an inert object to move when hit or pulled, and they are surprised when it does not. This result is consistent with prior research on infants’ responses to collision events involving inert objects (e.g., Kotovsky & Baillargeon, 2000; Wang et al., 2003).

Third, and most importantly for present purposes, the results of Experiments 3 and 3A make clear that 6-month-old infants are not surprised when a self-propelled object remains stationary when hit or pulled. These results suggest that infants endow a self-propelled object with an internal source of energy (e.g., Gelman, 1990; Gelman et al., 1995; Leslie, 1994, 1995) and assume that the object can use this energy to resist or counteract efforts to move it. As such, the present results are consistent with prior evidence that infants are not surprised when a self-propelled object does not move off immediately when hit (e.g., Leslie, 1982, 1984b; Leslie & Keeble, 1987; Oakes, 1994). Infants apparently assume that a self-propelled object can elect to go along with efforts to move it, or it can elect to resist these efforts—in which case it may choose to move after a delay, or not at all.

4.3.1. Links to prior findings: Expecting self-propelled objects to move again

Markson and Spelke (2006) adapted a paradigm developed by Pauen (2000; Träuble, Pauen, Schott, & Charalampidu, 2006) to examine infants’ ability to learn which object was inert and which was self-propelled in a pair of objects. In a series of experiments, 7-month-old infants watched two familiarization events involving two different wind-up toys from the same category (e.g., two animals, two vehicles, or two amorphous shapes consisting of the toy animals covered with various materials). In one event, an experimenter’s hand held one object (e.g., a bear) and moved it across the apparatus (inert event). In the other event, the hand held a different object (e.g., a rabbit) and released it; the object then moved across the apparatus until it was stopped by the hand (self-propelled event). During the test trials, the two objects stood apart and motionless on the apparatus floor, and the infants’ looking time at each object was measured. Analysis of the test data revealed that (1) the infants looked reliably longer at the self-propelled object, as though anticipating that it would move again, and (2) this result was obtained when the two objects were animals but not when they were vehicles or shapes. Markson and Spelke concluded that the infants could “reliably learn the property of self-propelled motion only for animate objects” (p. 67).

This conclusion is surprising in light of the results of the present experiments, where infants readily learned whether the box shown in the familiarization trials was inert or self-propelled. However, Shutts, Markson, and Spelke (in press) recently suggested that extraneous factors might have contributed to the differential results Markson and Spelke (2006) obtained with their animals, vehicles, and shapes. Specifically, when released by the hand, the animals moved in a way that clearly suggested they were self-propelled because they had various parts that moved independently (e.g., a mouth that opened or a head that bobbed up and down); in contrast, the vehicles and shapes moved rigidly across the apparatus, leaving open the possibility that the hand had set them in motion when releasing them. According to this interpretation, the infants failed to learn which object in each pair of vehicles or shapes was self-propelled simply because they received no clear evidence that either object was in fact self-propelled. To test their interpretation, Shutts et al. conducted experiments with vehicles and other objects that gave unambiguous evidence of self-propulsion (e.g., a truck that had independently moving parts and periodically changed direction or a shape that flipped over backwards several times). As predicted, and consistent with the findings of the present experiments, infants now learned which object was inert and which was self-propelled in all pairs of objects.