Abstract

Context

After menopause, women experience changes in body composition, especially increase in fat mass. Additionally, advancing age, decreased physical activity and increased inflammation may predispose them to develop type-2 diabetes. Isoflavones have been shown to improve metabolic parameters in postmenopausal women. However, the effect of isoflavones on adipo-cytokines remains unclear.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of high dose isoflavones on inflammatory and metabolic markers in postmenopausal women.

Study Design

We measured glucose, insulin and adipokines/cytokines in 75 healthy postmenopausal women who were randomized to receive 20 gm of soy protein with 160 mg of total isoflavones (64mg genistein, 63 mg diadzein, 34 mg glycitein) or 20 gm of soy protein placebo for 12 weeks. Women on estrogen discontinued therapy at least three months prior to the study. The supplements were given in a powder form and consumed once daily with milk or other beverages.

Results

Mean age in the placebo and active groups was similar (p=0.4). Average time since menopause was 9 yrs and two-thirds of the women underwent natural menopause. There was no significant difference in the BMI at baseline between the groups [placebo (25.1 kg/m2), active (26 kg/m2)] and it did not change significantly during the study. At baseline, placebo group had significantly higher levels of TNF-α (p<0.0001), otherwise there was no difference in any other parameter. After 12 weeks of treatment, there were significant positive changes in TNF-α levels within the placebo group (p<0.0001) and adiponectin levels within the isoflavones group (p=0.03). Comparison of pre-post change between the groups showed a small but significant increase in serum adiponectin levels in the isoflavone group (p=0.03) compared to placebo. No significant changes were seen in any other parameter between the two groups.

Conclusion

Healthy, normal-weight postmenopausal women may not experience improvement in metabolic parameters when given high dose isoflavones despite an increase in serum adiponectin levels. Role of isoflavones in obese and insulin resistant postmenopausal women needs exploration.

Introduction

Menopause is characterized by the cessation of menses due to loss of ovarian follicular activity. This typically occurs around the ages of 45 to 55 years and is characterized by hot flashes, decreased libido, and changes in body composition (1,2). These changes occur in the setting of decreasing estradiol, advancing age and changes in lifestyle that include lack of exercise and decreased fitness. These factors influence lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and may contribute to insulin resistance and diabetes in these women (3).

Changes in glucose homeostasis may be influenced by adipokines such as adiponectin, leptin, and resistin. The influence of hormonal alterations during menopause on circulating levels of these adipokines remain unclear (4,5). Leptin and resistin are known to increase in correlation to body fat, the latter of which has been found to mediate insulin resistance (6). Proinflammatory cytokines, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interluekin-6 (IL-6) are also produced by adipose tissue and are implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and diabetes (7). Since inflammation increases with aging, these cytokines may also contribute to insulin resistance in postmenopausal women (4).

In an effort to alleviate the effects of menopause, hormone replacement therapy with estrogen has been employed for decades. However, recent studies have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular disease with estrogen replacement (8, 9). Hence, a drive has been geared towards finding more natural sources of estrogen. Phytoestrogens are plant compounds with estrogen-like biological activity (10,11). There are three main classes of phytoestrogens: isoflavones, lignans and coumestans (10). Main sources of isoflavones include soy beans, flaxseed, legumes, etc with the major isoflavones being genistein, daidzein and glycitein. Phytoestrogens exhibit both estrogenic and antiestrogenic actions in vitro and in vivo, binding to the estrogen receptor and initiating transcriptional activity (12). Postmenopausal Japanese women have been reported to have a lower incidence of vasomotor symptoms which is believed to be due partly to the high isoflavone content of their diet (10). Epidemiological studies have shown that Japanese-American women in Seattle have higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance than those living in Tokyo (13,14). It is therefore thought that isoflavones in amounts similar to that used in Asian diet may protect against these metabolic perturbations.

Inclusion of isoflavones in the diet of postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome has been shown to improve glycemic control, insulin resistance and hemoglobin A1c (15, 16). However, the effect of isoflavones on metabolic and inflammatory markers like fasting glucose, insulin resistance, ghrelin, adipokines and cytokines in healthy postmenopausal women is unclear. This study was conducted to answer this question.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects and Study Design

Participants were ambulatory, community dwelling, English speaking women who were postmenopausal (natural and surgical) and had a serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level >30 mIU/mL and were recruited from the community (Baltimore metropolitan area) by advertising in newspapers, through study flyers and referrals from community physicians. Subjects taking estrogen were asked to discontinue therapy at least three months prior to enrollment. Women already taking soy supplements (soy milk, black cohosh, etc), were asked to discontinue these products for the duration of the study. Those who refused were excluded. Other exclusions included allergy to soy protein, history of breast cancer or abnormal mammograms, current use of glucocorticoids, serum triglycerides > 500 mg/dl, diabetes, liver disease, untreated thyroid disease, neurological disease, and untreated psychiatric disorders. All participants signed informed consent and the study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Randomization

Prior to recruitment, randomized numbers were generated by computer and assigned to soy protein vs placebo group. Both participants and study personnel were blinded to the group assignment. Non-study personnel dispensed the drug.

Intervention

The intervention was in the form of a soy powder (Revival Soy, Physicians Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Kernersville, NC), containing 20 g of soy protein consisting 160 mg total isoflavones (96 mg aglycones). The powder could be mixed with milk and other beverages. Isoflavone concentrations were 64 mg genistein, 63 mg diadzein, and 34 mg glycitein. Placebo powder (Physicians Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Kernerville, NC), contained 20 g of whole milk protein and equivalent nutrients contained in the active product, excluding isoflavones. Active and placebo powders were available in vanilla and chocolate flavors (dispensed according to subject’s taste preference), and looked and tasted similar. Subjects were asked to consume one packet daily. Supplements were dispensed at baseline and at 6-week visit. Compliance was judged by counting the number of unused packets returned by patients at week-6 and -12 of the study. This was then converted to percentage of prescribed packets that were ingested by the subjects. Subjects also reported days when packets were missed.

Laboratory Methods

Blood samples were collected from subjects at baseline and week-12 visits between 8-10 am after an overnight fast. Once collected, samples were centrifuged to separate serum that was used for all hormone measurements. Serum was stored at -80°C until assayed. Every assay was performed in duplicate for all subjects simultaneously and with the same standard curve in order to minimize errors.

Glycemic Parameters

Serum glucose concentrations were quantified using Beckman Glucose Analyzer 2 (Beckman Instruments, Inc., California, USA). This analyzer utilizes an oxygen rate method using an oxygen electrode. A sample is injected into enzyme reagent solution containing dissolved oxygen, and electronic circuitry is used to measure the rate of oxygen consumption from the sample, which is directly proportional to the glucose concentration. Precision for these glucose values had a standard deviation <2.5 mg/dl. Insulin concentrations were determined using a solid phase two-site enzyme immunoassay (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH) with intra- and interassay variation between 2.6 and 3.4%. Insulin resistance was assessed by using the Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMAIR) method [ HOMAIR :(glucose [mmol] * insulin [μlU/ml]) /22](17).

Adipo-cytokines

Serum leptin and resistin were measured using Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assays (ELISA). Resistin (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH) had intra-assay variations between 2.8 and 3.4% and inter-assay variation between 5.1-6.9%. Human leptin kit utilizes a direct sandwich based method (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). The coefficients of intra- and interassay variation were between 2.6 and 6.2%. Total ghrelin concentrations were calculated using competitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA). The intra- and interassay variations were between 6.7 and 15.3%. Adiponectin measurements also employed RIA (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) with intra- and interassay variations between 1.78 and 9.24%. Both IL-6 and TNF-α employ the quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The intra- and interassay precision for IL-6 was between 6.5 and 9.6% with a range of 0.428-8.87 pg/mL. The detection range of TNF-α was 0.585-2.139 pg/mL with an intra- and interassay variation between 3.1 and 10.6%. All interassay CVs were based on duplicate samples on more than one plate, using one standard curve.

Statistical Analysis

Prior to testing hypotheses and modeling, normality of the continuous variables was inspected by plotting histograms and via Shapiro-Wilks test, and the need for non-parametric analysis was determined. Comparisons of the changes in hormone measurements within treatment groups were measured using unpaired t-tests. For comparison between treatment groups, analysis was done for categorical demographic variables in Table 1 using chi-square tests. Comparisons between treatment groups of the changes in hormone measurements within groups shown in Figures 1 and 2 were done using unpaired t-tests. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of women in the active and placebo arms.

| Placebo (n = 43) | Active (n = 32) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs (mean) | 56.1 (0.84) | 57.3 (1.10) | 0.400 |

| Age in yrs (range) | 46-74 | 49-74 | |

|

Years since Menopause |

9.0 (2.0) | 9.1 (1.8) | 0.954 |

| Education | 0.568 | ||

| >= 16 yrs | 32 | 21 | |

| >= 12 & < 16 yrs | 11 | 11 | |

| < 12 yrs | 0 | 0 | |

| Race | 0.572 | ||

| Caucasian | 37 | 27 | |

| Blacks | 3 | 4 | |

| Other | 3 | 1 | |

| BMI | 25.1 (0.8) | 26.4 (0.9) | 0.266 |

| Current Smoking | 2 | 1 | 0.765 |

| Systolic BP | 118 (103, 125) | 120 (109, 137) | 0.195 |

| Diastolic BP | 70 (65, 81) | 72 (70, 80) | 0.965 |

| Pulse | 64 (60, 72) | 64 (60, 72) | 0.698 |

| Medical History | |||

| Hysterectomy | 8 | 4 | 0.693 |

| Oopherectomy | 1 | 2 | 0.793 |

| Lipid Medications | 7 | 9 | 0.340 |

| Antihypertensives | 4 | 5 | 0.662 |

| Multivitamins | 12 | 13 | 0.402 |

| Calcium | 12 | 9 | 0.811 |

|

Vitamin B Complex |

2 | 1 | 0.809 |

| Vitamin C | 1 | 5 | 0.101 |

| Vitamin D | 1 | 1 | 0.586 |

| Vitamin E | 5 | 5 | 0.873 |

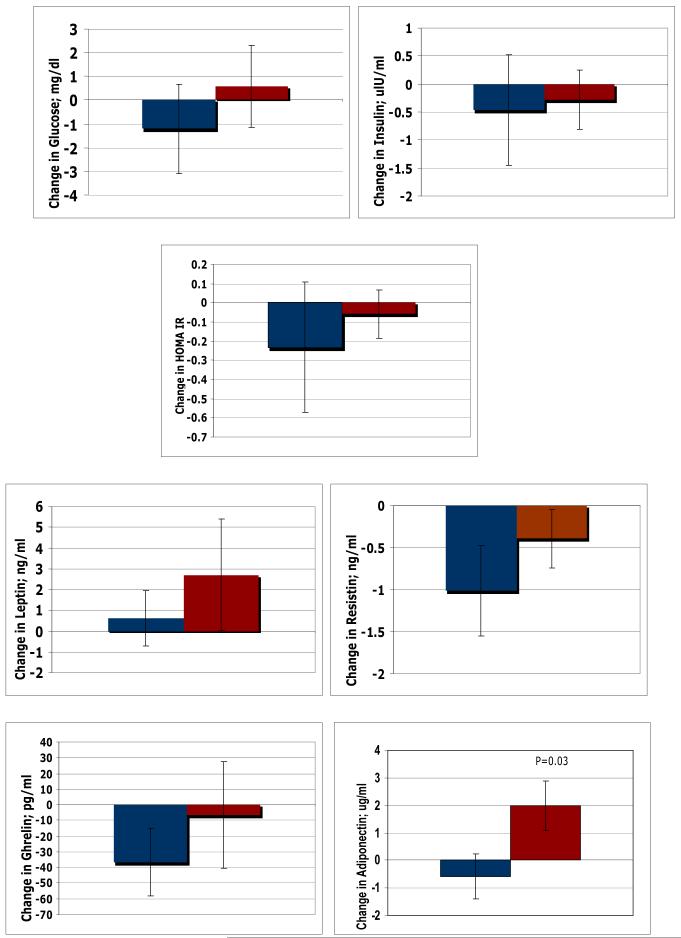

Figure 1.

Comparison of change in Plasma Glucose, Insulin, Adipokines and HOMA IR measured between Placebo and Soy arm at 12 weeks using unpaired T-tests.

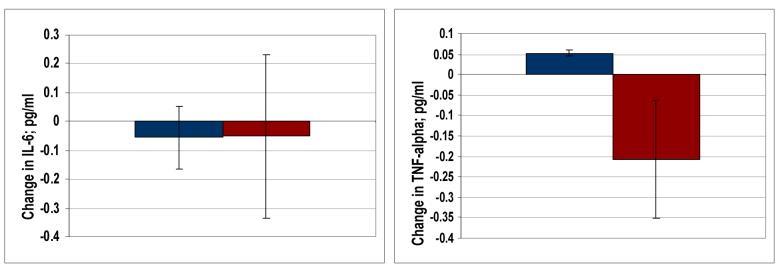

Figure 2.

Comparison of change in Plasma Cytokines measured between Placebo and Soy arm at 12 weeks using unpaired T-tests.

Results

Demographics

Ninety-three consecutive postmenopausal women were initially randomized. Two were excluded because of non-compliance while seven withdrew due to adverse effects. Hence, 84 women completed the original study evaluating quality of life and vasomotor symptoms (manuscript submitted). Out of these 84 women, seventy-five had serum samples of sufficient quantity for analysis of adipo-cytokines and metabolic parameters (32 active, 43 placebo). The majority of subjects were Caucasians (86%). The mean age was 56 years for the placebo group and 57 years for the active group. The average time since menopause was 9 years with two-thirds of the participants experiencing natural menopause. No major differences were present at baseline between the two groups (Table 1).

Hormones & Adipo/cytokines

At baseline, placebo group had significantly higher levels of TNF-α (p<0.0001), otherwise there was no difference in any other parameter. After 12 weeks of treatment, there were significant positive changes in TNF-α levels within the placebo group (p<0.0001) and adiponectin levels within the isoflavones group (p=0.03). Comparison of pre-post change between the groups showed a small but significant increase (p=0.03) in serum adiponectin levels in the isoflavone group compared to placebo (Figure 1). No significant changes were seen in any other parameters between the two groups (Figures 1 & 2).

Discussion

Changes in glucose metabolism are seen in women after menopause that occurs in the setting of declining estrogen levels, advancing age and alterations in fat distribution (3). Several investigations have confirmed that insulin resistance is significantly higher in postmenopausal women compared to their premenopausal counterparts (4). These factors may predispose these women to develop cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes (18). Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with estrogen has been shown to improve glucose homeostasis in some studies (19, 20). However, unfortunately HRT has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk (8, 9). In contrast, phytoestrogens have been associated with decreased cardiovascular risk (21). Indeed, studies have shown improvement in inflammatory cytokines with isoflavone treatment (22), however, these findings have not been universal (23). Our randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed no significant benefits in any of the glycemic parameters after 3 months of high dose (160 mg) isoflavones despite a significant increase in serum adiponectin levels in the soy group.

Soy is a staple of diet in Asian countries with consumption reaching as much as 50-100 mg daily (24). In contrast, the estimated intake of isoflavones by American women is <1 mg/d (25). Epidemiological data shows that Japanese-Americans living in Seattle have a four times higher prevalence of type-2 diabetes than those living in Tokyo (13, 14). This suggests beneficial role of soy on metabolic parameters. Indeed, studies assessing the effects of phytoestrogens in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome and type-2 diabetes have shown beneficial effects on glucose homeostasis (15,16). Jayagopal et al have shown that 132 mg of isoflavones improves insulin resistance and HbA1c in postmenopausal women with type-2 diabetes (16). The mechanisms behind anti-diabetic effects of isoflavones include inhibition of intestinal brush border uptake of glucose and tyrosine kinase inhibitory properties (26). The hope has been that isoflavones will be a successful alternative for estrogen therapy, not only in terms of menopausal symptoms, but also other health benefits such as altered glucose metabolism and insulin resistance encountered with menopause. Unfortunately, the studies of isoflavones have shown inconsistent results on metabolic parameters in postmenopausal women. Nikander et al used 114 mg of soy for 3 months in 56 women with breast cancer and found no beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity (27). Although we used higher dose of isoflavones (160 mg) in healthy women, however, our results were similar to their study. One explanation of this lack of benefit could be the fact that these women were relatively healthy and close to ideal body weight. Hence, there may have been little room for improvement in their metabolic parameters despite a significant increase in serum adiponectin in the soy group.

Since there is an increase in fat mass with menopause, adipokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance (28). Elevated serum resistin levels have been associated with glucose intolerance while elevated adiponectin levels, as occurs with thiazolidinedione therapy, is associated with improved insulin sensitivity (28). Our study showed that serum adiponectin levels increased in women taking high-dose isoflavones compared to placebo. Generally speaking, serum adiponectin levels are decreased in obesity and type-2 diabetes and this is considered to be of etiological importance in causing insulin resistance (5,6). Therefore, any measure that increases adiponectin levels would be predicted to improve insulin resistance. However, as our subjects had normal insulin sensitivity to start with (based on fasting insulin/glucose levels), we could not demonstrate any effect on metabolic parameters by increased adiponectin levels. However, in obese women or those with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes, one may have seen the beneficial effect of rise in adiponectin levels on metabolic parameters.

Metabolic effects of ghrelin include increased appetite, glucose oxidation and lipogenesis (6). Contrary to our results, some studies have demonstrated decreased levels of ghrelin after as little as 8 weeks of low dose isoflavones (27). Further inconsistencies exist on the effects of phytoestrogens on inflammatory cytokines. Both TNF-α and IL-6 are known to cause insulin resistance. The former causes it directly by down-regulating insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), inducing serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and by decreasing glucose transporting protein-1 (GLUT-1) (28). On the other hand, IL-6 causes it by decreasing the activation of IRS-1 (28). Studies have suggested a decrease in the circulating levels of TNF-α after treatment with low dose isoflavones in 12 postmenopausal women (22). Although our study had a much higher sample size, we did not observe any decrease in these cytokines in the soy group compared to placebo. We believe that the anti-inflammatory role of soy should be further explored in large prospective trials in obese or insulin-resistant women.

Our study has a few limitations. First, we did not measure serum or urine levels of isoflavones, hence, it is uncertain how much of the soy protein was actually absorbed. The method of counting sachets, however, has been the most common method in many studies and the compliance rate of our study was very high. Second, we did not measure body composition. Lastly, serum levels of adipokines and cytokines do not necessarily reflect tissue concentrations. Hence, any influence of isoflavones on tissue levels of these markers cannot be ruled out. Our study also has a few strengths. It has a reasonably large sample size compared to previous studies and the breadth of adipo-cytokines measured affords some confidence to the results obtained.

In conclusion, supplementation with isoflavones at a concentration consumed by the Asian population did not infer any benefits on markers of glucose homeostasis (despite an increase in serum adiponectin levels). However, the role of soy in obese and diabetic postmenopausal women needs further exploration.

Table 2.

Plasma Glucose, Insulin, Adipokines and HOMA IR measured at baseline and post-treatment

| Placebo (n=43) |

p-value | Soy (n=32) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPG (mg/dl) before | 86.1 +/- 2.09 | 0.64 | 83.8 +/- 1.68 | 0.71 |

| FPG (mg/dl) after | 84.9 +/- 1.48 | 84.6 +/- 1.27 | ||

| Insulin (μIU/ml) before | 5.69 +/- 0.97 | 0.68 | 5.62 +/- 0.55 | 0.69 |

| Insulin (μIU/ml) after | 5.23 +/- 0.52 | 5.33 +/- 0.47 | ||

| HOMAIR before | 1.33 +/- 0.34 | 0.52 | 1.19 +/- 0.13 | 0.73 |

| HOMAIR after | 1.10 +/- 0.11 | 1.13 +/- 0.11 | ||

| Leptin (ng/ml) before | 25.2 +/- 2.84 | 0.88 | 25.9 +/- 2.97 | 0.52 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) after | 25.8 +/- 2.85 | 28.6 +/- 2.95 | ||

| Resistin(ng/ml) before | 4.08 +/- 0.58 | 0.11 | 3.81 +/- 0.37 | 0.42 |

| Resistin(ng/ml) after | 3.07 +/- 0.23 | 3.42 +/- 0.31 | ||

|

Adiponectin (ug/ml) before |

19.7 +/- 1.09 | 0.72 | 18.6 +/- 1.67 | 0.38 |

| Adiponectin (ug/ml) after | 19.2 +/- 1.26 | 20.6 +/- 1.54 | ||

| Ghrelin (pg/ml) before | 357.7 +/- 32.26 |

0.71 | 371.6 +/- 45.16 |

0.73 |

| Ghrelin (pg/ml) after | 340.2 +/- 31.70 |

350.5 +/- 38.26 |

Values are expressed as mean +/- SEM

Table 3.

Plasma Cytokine Levels of Postmenopausal Women at Baseline and post-treatment

| Placebo (n=43) |

p-value | Soy (n=32) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6(pg/ml) before | 1.61 +/- 0.15 | 0.79 | 2.18 +/- 0.31 |

0.89 |

| IL-6(pg/ml) after | 1.56 +/- 0.14 | 2.12 +/- 0.27 |

||

| TNF-α (pg/ml) before | 0.61 +/- 0.01 | 0 | 1.93 +/- 0.27 |

0.56 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) after | 0.66 +/- 0.10 | 1.72 +/- 0.22 |

Values are expressed as mean +/- SEM

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McKinlay SM. The normal menopause transition: an overview. Maturitas. 1996;23:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00985-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landgren B-M, Collins A, Csemiczky G, Burger HG, Baksheev L, Robertson DM. Menopause Transition: Annual Changes in Serum Hormonal Patterns over the Menstrual Cycle in Women during a Nine-Year Period Prior to Menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2763–2769. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaspard UJ, Gottel JM, Van Den Brule AF. Postmenopausal changes of lipid and glucose metabolism: a review of their main aspects. Maturitas. 1995;21:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00901-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Wada K, Matsushita K, Otsuka R, Yang PO, Sugiura K, Hotta Y, Mitsuhashi H, Takefuji S, Kondo T, Toyoshima H. The transition to menopause reinforces adiponectin production and its contribution to improvement of insulin-resistant state. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu MC, Cospe P, Orio F, Crmina E, Lobo R. Insulin resistance in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome and the measurements of adiponectin, leptin, and ghrelin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budak E, Sanchez MF, Bellver J, Cervero A, Simon C, Pellicer A. Interactions of hormones lepin, ghrelin, adiponectin, resistin, and PYY3-36 with the reproductive system. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1563–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2548–2556. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murkies A, Wilcox G, Davis S. Clinical Review 92: Phytoestrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:297–303. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.2.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight DC, Eden J. A review of the clinical effects of phytoestrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:897–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird D, Umbach D, Lansdell L, Hughes C, Setchell K, Weinberg C, Haney A, Wilcox A, McLachlan J. Dietary Intervention Study to Assess estrogenicity of Dietary Soy among Postmenopausal Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1685–1690. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7745019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto WY, Bergstrom RW, Boyko EJ, Kinyoun JL, Leonetti DL, Newell-Morris LL, Robinson LR, Shuman WP, Stolov WC, Tsunehara CH. Diabetes and risk factors in second- and third-generation Japanese Americans in Seattle, Washington. Diabetes Res Clin Prac. 1994;24:S43–S52. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto WY, Leonetti DL, Bergstrom RW, Kinyoun JL, Stolov WC, Wahl PW. Glucose intolerance and diabetic complications among Japanese-American women. Diabetes Res Clin Parct. 1991;13:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(91)90042-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azadbakht L, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A, Padyab M, Hu FB, Willet W. Soy inclusion in the diet improves features of the metabolic syndrome: a randomized crossover study in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:735–741. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayagopal V, Jennings P, Albertazzi P, Hepburn D, Kilpatrick E, Atkin S, Howarth E. Beneficial Effects of Soy Phytoestrogen Intake in Postmenopausal Women With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1709–1714. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espeland M, Schrott H, Hogan P, Waclawiw M, Fineberg E, Bush T, Howard G. Effect of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy on Glucose and Insulin Concentrations. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1589–1595. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson B, Mattsson LA, Hahn L, Mårin P, Lapidus L, Holm G, Bengtsson BA, Björntorp P. Estrogen replacement therapy decreases hyperandrogenicity and improves glucose homeostasis and plasma lipids in postmenopausal women with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:638–643. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown MD, Korytkowski MT, Zmuda JM, McCole SD, Moore GE, Hagberg JM. Insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: independent and combined associations with hormone replacement, cardiovascular fitness, and body composition. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1731–1736. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan A, Phipps W, Kurzer M. Phyto-oestrogens. Best Practice & Research Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17:253–271. doi: 10.1016/s1521-690x(02)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Cao S, Nagamani M, Anderson KE, Grady JJ, Lu LJ. Decreased circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in postmenopausal women during consumption of soy-containing isoflavones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3956–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikander E, Tiitinen M, Ylikorkala O. Evidence of a Lack of Effect of a Phytoestrogen Regimen on the Levels of C-Reactive Protein, E-Selectin, and Nitrate in Postmenopausal Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5180–5185. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Zheng W, Custer LJ, Dai Q, Shu XO, Jin F, Franke AA. Usual dietary consumption of soy foods and its correlation with the excretion rate of isoflavones in overnight urine samples among Chinese women in Shanghai. Nutr Cancer. 1998;33:82–7. doi: 10.1080/01635589909514752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleijn JJM, Van der Scouw Y, Wilson P, Adlercreutz H, Mazur W, Grobbee D, Jacques P. Intake of Dietary Phytoestrogens Is Low in Postmenopausal Women in the United States: The Framingham Study. J Nutr. 2001;131:1826–1832. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vedavanam K, Srijayanta S, O’Reilly J, Raman, Wiseman H. Antioxidant Action and Potential Antidiabetic Properties of an Isoflavonoidcontainig Soyabean Phytochemical Estract (SPE) Phytoper. Res. 1999;13:601–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199911)13:7<601::aid-ptr550>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikander E, Tiitinen A, Laitinen K, Tikkanen M, Ylikorkala O. Effects of isolated isoflavonoids on lipids, lipoproteins, insulin sensitivity, and ghrelin in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3567–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnr P. Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes — Role of the Adipokines. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:333–339. doi: 10.2174/1566524053766022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]