Abstract

Objective

To assess urinary frequency in community-dwelling women.

Study design

Voiding habits were assessed in 4,061 women ages 25–84 using survey responses from the Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire. Bother related to daytime and nighttime frequency was assessed with 100 mm visual analog scales and compared using t-tests and ANOVA.

Results

Median daytime frequency was every 3–4 hours. Urinary frequency ≥ every 2 hours occurred in 27% and was more bothersome than every 3–4 hours or less (51.7 ± 30.1 vs. 23.6 ± 23.7 mm, p < 0.001). Nocturia was reported in 72%, while 33% had ≥ 2 voids per night. Bother increased with increasing nighttime frequency (27.3 ± 26.3 for 1 vs. 57.3 ± 28.5 for ≥ 2 times, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Bothersome urinary frequency is common and occurs when frequency is at least every 2 hours by day and more than once per night.

Keywords: bother, nocturia, pelvic floor disorders, urinary frequency, voiding

INTRODUCTION

Symptoms of urinary frequency and nocturia are common and associated with significant negative impact on health-related quality of life. 1,2,3 Despite this, little normative data exists for daytime and nighttime urinary voiding frequency in community-dwelling women. The wide discrepancies in published population-based prevalence estimates are likely a function of the populations sampled, the varying definitions used for frequency, and lack of consensus on clinically significant thresholds. A commonly adhered to definition of urinary frequency is voiding more than seven times during the day and more than once per night.4 However, attempts to standardize the definitions of both daytime and nighttime frequency have been unsuccessful.5

The Report from the Standardization Sub-committee of the International Continence Society (ICS) on the Terminology of Lower Urinary Tract Function defines ‘increased daytime frequency’ as the complaint that the individual voids too often by day, and ‘nocturia’ as the complaint that the individual has to wake at night one or more times to void.6 Published estimates of the prevalence of nocturia using the ICS definition range from 30 to 55% and population-based prevalence estimates for increased daytime frequency are sparse. 1,2,

Using data from the Kaiser Permanente Continence Associated Risk Epidemiology Study (KP CARES)7, we aimed to (1) assess the prevalence and degree of bother related to daytime and nighttime urinary frequency in a large, age-diverse, community-dwelling population of women so as to establish evidence-based normative clinical reference values, and (2) to assess the relationship between daytime and nighttime urinary frequency and demographic and clinical characteristics including pelvic floor disorders (PFD). Our hypotheses were that voiding more frequently than every 2 hours and more than once per night would be associated with significantly increased bother, and that frequent voiding would be significantly associated with having one or more PFD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A sub-analysis of subjects enrolled in KP CARES was performed to describe the voiding habits of community-dwelling women. The details of the KP CARES study have been described elsewhere.7 In summary, this was a large cross-sectional epidemiologic study that used a questionnaire validated to identify pelvic floor disorders.8 A total of 12,200 women (3,050 from each of 4 age groups between 25 and 84 years) were selected randomly from the 950,000 women enrolled in a large health maintenance organization (Kaiser Permanente Southern California). Subjects were identified using administrative data, which included age, sex, enrollment history, and current address and phone number. The condition definitions, and results of psychometric and criterion validation of the Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire (EPIQ) have been previously reported.8,9

The survey also included questions specifically related to daytime and nighttime voiding habits.8 Daytime urinary frequency was assessed using the question: “During waking hours, how frequently do you need to empty your bladder?” Responses were categorized as less than every 6 hours, every 5 to 6 hours, every 3 to 4 hours, every 1 to 2 hours, and more than once per hour. Nocturia was assessed with the question “Do you awaken during your normal sleeping hours to urinate?” Nighttime urinary frequency was assessed with the question “How many times on average do you need to empty your bladder during sleeping hours?” Responses were categorized as once, 2 times, 3 times, 4 times, and 5 or more times. Degree of bother related to each response to daytime and nighttime urinary frequency was assessed using a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS). For the analysis of the association between subject characteristics and abnormal urinary frequency, we defined frequent daytime voiding as at least every 2 hours and frequent nighttime voiding as 2 or more voids per night.

The survey also included questions about demographics (age, race/ethnicity, and marital status), anthropometry (height, weight), behaviors (smoking, caffeine intake, chronic lifting), medical co-morbidities (diabetes, neurologic disease, depression, lung disease), obstetric history, pelvic surgery, menopause status, hormone exposure, recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI, more than 3 per year), and the presence of PFD (pelvic organ prolapse [POP], stress urinary incontinence [SUI], overactive bladder [OAB], and anal incontinence [AI]).

Age was calculated in completed years on the date of survey completion, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters and dichotomized into non-obese (< 30 kg/m2) or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Parity was calculated based on the reported number of pregnancies minus the number of abortions and ectopic pregnancies. Hormone exposure was categorized into never, past, or current use. Smoking was categorized as never smoked, past smoker (> 100 cigarettes) or current smoker. Chronic lifting was defined as repetitive lifting of more than 9 kg regularly for more than one year. Caffeine intake was defined as more than one cup of caffeinated beverage per day. Mode of delivery was based on self-reported pregnancy and delivery experience. As the primary purpose of KP CARES was to examine the association between pregnancy and mode of delivery on the prevalence of PFD, we defined the nulliparous group as those women who had never been pregnant or had only delivered a baby less than or equal to 2 kg. The cesarean delivery group was defined as having been delivered by one or more cesarean deliveries and having had no vaginal births exceeding 2 kg. Vaginally parous women were defined as having one or more vaginal deliveries exceeding 2 kg birth weight regardless of history of cesarean delivery.7 The definitions of POP, SUI, OAB, and AI were validated against a combination of physical examination findings and symptoms bothersome enough to seek treatment when the EPIQ was developed.

Power calculations were based on the primary objective of the study to identify the prevalence and risk factors for PFD. Post hoc power calculations determined that the current sample size had greater than 99% power to detect the differences in degree of bother between those with and without frequent daytime and frequent nighttime voiding. ANOVA and Students t-tests were used to compare VAS scores. Chi-square tests were used to compare prevalence of conditions associated with frequent daytime or nighttime voiding and multiple logistic regression was used to assess the relative impact of confounding factors on the presence of frequent daytime or nighttime voiding. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Associations at a two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Of the 4,458 (37%) surveys returned, 140 were in Spanish and 4,318 in English. The racial/ethnic composition of the final study sample was consistent with the Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership: 60% non-Hispanic White, 20% Hispanic, 10% African American, 8% Asian-Pacific Islander, 1% Native American, and 1% other or unknown. Non-responders were significantly younger than responders (53 ± 17 vs. 57 ± 16 years, p < 0.001). Other medical, historical and demographic data for non-responders are not available for comparison. Of the respondents, 4,061 (91%) had sufficient information for analysis of daytime voiding habits and 4,038 (91%) had sufficient information to evaluate nighttime voiding habits. More than 97% of these had adequate responses to accurately assess degree of bother related to daytime and nighttime urinary frequency.

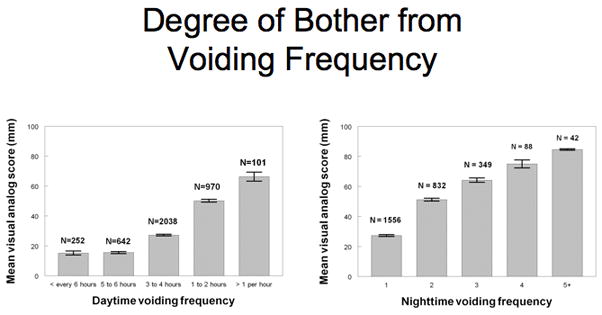

The median daytime frequency of voiding was every 3 to 4 hours. Six percent of women voided less than every 6 hours, 16% every 5 to 6 hours, 51% every 3 to 4 hours, 24% every 1 to 2 hours and 3% more than every hour. Twenty-seven percent met the criteria for frequent daytime voiding. Each interval increase in daytime frequency was associated with significantly increased degree of bother as measured on the VAS (Figure 1. p < 0.001). Overall, the mean VAS for frequency of less than every 2 hours was 23.6 ± 23.7 vs. 51.7 ± 30.1 mm for ≥ every 2 hours (p < 0.001). A total of 72% reported any nighttime voiding and 33% had 2 or more episodes per night (frequent nighttime voiding). Figure 1 also shows increasing bother with increasing nighttime urinary frequency (mean VAS 27.3 ± 26.3 for 1 time per night vs. 57.3 ± 28.5 for ≥ 2 times per night, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Before adjustment for potential confounders, multiple factors were significantly associated with frequent daytime and nighttime voiding (Tables 1 and 2). In univariate analysis, women who reported frequent daytime and nighttime voiding were significantly older than unaffected women (p<0.001). The age distribution of women reporting frequent daytime voiding was: 24% (ages 25–39), 28% (ages 40–54), 30% (ages 55–69) and 24% (ages 70–84), p<0.01. The age distribution of women reported frequent nighttime voiding was: 18% (ages 25–39), 24% (ages 40–54), 33% (ages 55–69) and 50% (ages 70–84), (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with and without frequent daytime voiding.

| Normal daytime voiding (> every 2 hours) N = 2957 | Frequent daytime voiding (≤ every 2 hours) N = 1081 | P VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| AGE (mean yrs±SD) | 56.5 ±16.1 | 62.3 ± 14.7 | <0.001* |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | 0.93‡ | ||

| Caucasian | 60% | 64% | |

| Hispanic | 19% | 19% | |

| Black | 10% | 8% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8% | 7% | |

| Other/Unknown | 2% | 3% | |

| CLINICAL | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 6.1 | 28.0 ± 6.5 | <0.001* |

| Obesity ( ≥ 30 kg/m2 ) (%) | 26% | 32% | <0.001‡ |

| PARITY median (range) | 2 (0 – 17) | 2 (0 – 14) | 0.491† |

| DELIVERY MODE | 0.749§ | ||

| Vaginally Parous | 71% | 71% | |

| Cesarean Birth Only | 9% | 10% | |

| Nulliparous | 19% | 19% | |

| HORMONE/MENOPAUSAL | <0.001‡ | ||

| STATUS | |||

| Pre - Menopausal | 32% | 28% | |

| Post - No HT | 25% | 21% | |

| Post - Past HT | 30% | 35% | |

| Post - Current HT | 13% | 17% | |

| ANY PELVIC SURGERY (%) | 31% | 36% | 0.007‡ |

| DEPRESSION (%) | 19% | 23% | 0.004‡ |

| NEUROLOGIC DISEASE (%) | 3% | 2% | 0.538‡ |

| UTI > 3/yr (%) | 17% | 25% | <0.001‡ |

| DIABETES (%) | 11% | 13% | 0.094‡ |

| LUNG DISEASE/ASTHMA (%) | 13% | 14% | 0.320‡ |

| SMOKING (%) | 0.320‡ | ||

| Non-smoker | 62% | 60% | |

| Past smoker | 29% | 30% | |

| Current smoker | 9% | 10% | |

| DIURETIC USE (%) | 21% | 23% | 0. 176‡ |

| CAFFEINE (> 1cup/day) (%) | 55% | 59% | 0.041‡ |

| PELVIC FLOOR DISORDERS | |||

| POP (%) | 5% | 10% | <0.001‡ |

| SUI (%) | 11% | 28% | <0.001‡ |

| OAB (%) | 6% | 32% | <0.001‡ |

| AI (%) | 22% | 35% | <0.001‡ |

| Any PFD (%) | 31% | 55% | <0.001‡ |

T-test

Mann-Whitney U test

chi squared analysis

Kruskal-Wallis

SUI, stress urinary incontinence; OAB, overactive bladder; POP, pelvic organ prolapse;

AI, anal incontinence; PFD, pelvic floor disorder; HT, hormone therapy; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with and without frequent nighttime voiding.

| Normal nighttime voiding (< 2 voids per night) N = 2926 | Frequent nighttime voiding (≥ 2 voids per night) N = 1331 | P VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| AGE (mean yrs ± SD) | 53.6 ±15.6 | 62.3 ± 14.7 | <0.001* |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | 0.143† | ||

| Caucasian | 65% | 34% | |

| Hispanic | 70% | 28% | |

| Black | 61% | 38% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 71% | 28% | |

| Other/Unknown | 62% | 35% | |

| CLINICAL | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 5.7 | 28.6 ± 7.0 | <0.001* |

| Obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2 ) (%) | 24% | 34% | <0.001‡ |

| PARITY median (range) | 2 (0 – 17) | 2 (0 – 14) | <0.001† |

| DELIVERY MODE | <0.001§ | ||

| Vaginally Parous | 64% | 34% | |

| Cesarean Birth Only | 71% | 28% | |

| Nulliparous | 71% | 27% | |

| HORMONE/MENOPAUSE | <0.001§ | ||

| STATUS | |||

| Pre-Menopausal | 81% | 18% | |

| Post - No HT | 59% | 38% | |

| Post - Past HT | 58% | 41% | |

| Post - Current HT | 61% | 37% | |

| ANY PELVIC SURGERY (%) | 26% | 44% | <0.001‡ |

| DEPRESSION (%) | 18% | 25% | <0.001‡ |

| NEUROLOGIC DISEASE (%) | 2% | 4% | <0.001‡ |

| UTI > 3/year (%) | 15% | 26% | <0.001‡ |

| DIABETES (%) | 8% | 18% | <0.001‡ |

| LUNG DISEASE/ASTHMA (%) | 11% | 18% | <0.001‡ |

| SMOKING (%) | 0.367§ | ||

| Non-smoker (never) | 61% | 37% | |

| Past smoker | 62% | 37% | |

| Current smoker | 74% | 24% | |

| DIURETIC USE (%) | 18% | 30% | <0.001‡ |

| CAFFEINE (> 1cup/day) (%) | 57% | 54% | 0.08‡ |

| PELVIC FLOOR DISORDERS | |||

| POP (%) | 5% | 10% | <0.001‡ |

| SUI (%) | 10% | 26% | <0.001‡ |

| OAB (%) | 5% | 30% | <0.001‡ |

| AI (%) | 21% | 34% | <0.001‡ |

| Any PFD (%) | 29% | 54% | <0.001‡ |

T-test

Mann-Whitney U test

chi squared analysis

Kruskal-Wallis

SUI, stress urinary incontinence; OAB, overactive bladder; POP, pelvic organ prolapse;

AI, anal incontinence; PFD, pelvic floor disorder; HT, hormone therapy; UTI, urinary tract infection.

After adjustment for confounders, the most significant factor associated with frequent daytime voiding was the presence of any one or more PFD (OR, 95% CI) (2.54, 2.15–3.01). Other significant conditions associated with frequent daytime voiding included: recurrent UTI (1.38, 1.13–1.70) and obesity (1.20, 1.01–1.44). Separate models substituting each individual PFD revealed that frequent daytime voiding was significantly associated with: POP (2.01, 1.50–2.70), SUI (3.41, 2.78–4.18), OAB (7.06, 5.64–8.84), and AI (1.86, 1.56–2.22). Given the obvious association between frequent daytime voiding and the presence of pelvic floor disorders, particularly OAB, we also analyzed separate models excluding PFD, but including all other significant variables. Associations between recurrent UTI (1.63, 1.34–1.97) and obesity (1.36, 1.12–1.59) remained, but no other variables were significantly associated.

For frequent nighttime voiding, the presence of any one or more PFD was the condition most significantly associated (2.29, 1.93–2.72). Other associated conditions included increasing age (1.58, 1.45–1.72 per 15 year age group), frequent UTI (1.59, 1.29–1.97), diabetes (1.62, 1.23–2.13), pulmonary disease (1.38, 1.08–1.76), obesity (1.38, 1.14–1.66), and history of pelvic surgery (1.30, 1.08–1.57). Separate models substituting any PFD for each individual disorder revealed that frequent nighttime voiding was significantly associated with each PFD: POP (1.68, 1.22–2.30), SUI (2.71, 2.17–3.38), OAB (5.30, 4.13–6.79) and AI (1.57, 1.31–1.88). Regression models excluding PFD did not markedly change the odds ratios for the additional confounders, however a significant association with neurologic disease was also found: increasing age (1.59, 1.46–1.73), recurrent UTI (1.84, 1.40–2.25), diabetes (1.71, 1.31–2.23), pulmonary disease (1.38, 1.09–1.75), neurologic disease (1.84, 1.06–3.20), obesity (1.52, 1.27–1.82), and history of pelvic surgery (1.34, 1.12–1.60).

COMMENT

Lack of uniformity in the definition of symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction, specifically what defines normal and abnormal daytime and nighttime voiding frequency, has hindered physicians in the appropriate diagnosis and treatment of bothersome urinary frequency. Although current ICS definitions for “increased urinary frequency” include the concept of bother, there is no consensus on what frequency of voiding per day or night constitutes bothersome symptoms in a large community-based population. Without agreement on what is normal and abnormal daytime and nighttime voiding frequency, our understanding of the true extent of the prevalence and impact of these conditions is severely limited.

Our study uniquely quantifies bothersome daytime and nighttime urinary frequency and demonstrates that the conditions are common among community-dwelling women, and associated with PFD. In this cohort, more than half of women (51%) reported a daytime urinary frequency of every 3 to 4 hours and three quarters reported urinating at least once per night, suggesting that nocturia, as currently defined by the ICS, is normal. Assuming a 16-hour day, our median daytime voiding frequency of every 3 to 4 hours correlates with 5.3 voids per day. This number is consistent with published estimates for normal urinary frequency of 5.5 to 6.7 voids per day.10,11 Nearly one-third of women reported daytime urinary frequency of every 2 hours or more and a similar number reported nighttime urinary frequency of 2 or more voids per night. Prevalence estimates for nocturia using the ICS definition have been reported between 39% and 41% in community dwelling men and women.2,12,13 In a large multi-national population-based study of women, 55% reported nocturia while 24% reported 2 or more voids per night.1 Our findings exceed these high prevalence estimates (72%) when using the ICS definition for nocturia, and are in concert with those using the criteria of 2 or more voids per night.

Our findings of nearly two-fold higher bother scores in women who reported frequent daytime and nighttime voiding compared to unaffected women supports existing evidence that increasing voiding frequency is associated with increased bother. 3,14,15 Coyne and colleagues reported that a urinary frequency of 8 or more times per day had a significant negative impact on health related quality of life, with reduced scores on all OAB subscales, three of the SF-36 subscales (general health, social function and mental health), and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.3 In addition, they reported significant increases in symptom bother in women with a urinary frequency of 8 or more times per day compared to those who voided less frequently. Others have found higher bother associated with number of nocturic episodes, with a significant increase in degree of bother as the number of voids increased to 2 or more voids per night compared to 0 or 1 voids per night.14,15 Based on this data and our findings of nearly two-fold higher bother from increased daytime and nighttime frequency, we recommend that abnormal (or “increased”) voiding frequency be considered when daytime voiding occurs at least every 2 hours and nighttime frequency (or “nocturia”) exceeds once per night during sleeping hours.

Several correlates of increased voiding frequency were identified in this cohort of women. The presence of PFD was the condition most significantly associated with increased or frequent daytime and nighttime voiding. Obesity and recurrent UTI were also significantly associated with frequent daytime and nighttime voiding regardless of the presence of one or more PFD. Interestingly, conditions commonly felt to be associated with increased daytime urinary frequency including increasing age, diuretic use, and caffeine use were not major contributors to frequent daytime voiding after controlling for confounders. While others have found urinary frequency to be independently associated with diuretic use,16 and caffeine17 similar associations with increased or bothersome daytime frequency were not found in this community-dwelling population after controlling for confounders. This contradiction may be attributable to the population studied, the adjustment for important covariates in the present study, or our definition of daytime frequency which incorporated degree of bother. With respect to age, other population-based studies have also failed to corroborate a significant relationship between daytime urinary frequency and increasing age.18 Frequent nighttime voiding was strongly associated with the presence of each of the four PFD, but was also associated with several other conditions including, recurrent UTI, diabetes, pulmonary disease, obesity and pelvic surgery; suggesting a disease process that is distinct from frequent daytime voiding. Epidemiologic studies such as ours examining the link between PFD and voiding frequency are complicated by the obvious association between voiding and PFD, particularly OAB whose definition includes urinary frequency and nocturia. In order to address this issue, multiple logistic regression models were repeated excluding PFD. There was little impact on the odds ratios for other confounders except for the addition of neurologic disease as a correlate of nocturia when PFD was excluded. Nevertheless, Coyne et al found that 67% of those with OAB reported more than 1 void per night and 42% reported more than 2 voids night compared to 31% and 14% respectively for unaffected women.2 These definitions, however, did not assess degree of bother related to frequency of nighttime voiding.

The association between nocturia and increasing age has been well-described and is confirmed by our findings.2,12,13 Similarly, Parsons et al found that nighttime voiding increases with increasing age, supporting previously published suggestions that the increase is related to a combination of an increase in nighttime urine production and a decrease in nighttime average volume voided.10 Similarly, the associations between nocturia and increasing BMI, diabetes, and pulmonary disease have been established in the literature, and are confirmed by our findings.19,20,21 The association of both frequent daytime and nighttime voiding with urinary tract infection is not surprising given the irritative voiding symptoms that characterize UTI, however a paucity of data exists on the relationship between UTI and voiding frequency.

The strengths of this study include its large, racially/ethnically and age diverse cohort of community-dwelling women and the use of a validated instrument to identify the presence of a variety of PFD. In addition to urinary frequency, the questionnaire also allowed us to assess degree of bother, thus permitting us to closely approximate “increased frequency” as defined by the ICS. The limitations of our study are that the voiding questions with frequency responses used did not encompass a full spectrum of voiding frequencies (for example, every 1, 2, 3 hours) but instead used predefined categories. However, during the validation process for EPIQ, focus group testing and test-retest reliability suggested categorical responses were more appropriate and correlation coefficients between voiding diaries and responses on EPIQ were very good (r = 0.79) Additionally, the number of hours of sleep per night was not measured, perhaps a significant omission given evidence to suggest the number of voids per night is significantly associated with the number of hours of sleep per night.2 Finally, our response rate was lower than anticipated despite considerable effort to increase it. Nevertheless, a response rate of 37% is typical of large epidemiologic studies, and we cannot postulate any reason why non-responders would have a significantly different urinary frequency than responders. Therefore, we do not believe that this low response rate introduced any important response bias. Common to population-based surveys without urinary diaries, there is also potential inaccuracy of self-reported symptoms of voiding frequency on a questionnaire. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to an uninsured population, but we have no biological reason to expect the uninsured women have different voiding habits than insured women.

The ICS definition of ‘increased daytime frequency, that is ‘the complaint by the patient who considers that he/she voids too often by day’,’6 appears to correlate well with a cut-point of every 2 hours or more given the marked increase in degree of bother related to voiding every 2 hours or more frequently. Similarly, bother related to a nighttime urinary frequency of two or more times per night was twice that of women who voided only once per night. Our data suggest that one void per night is part of the normal clinical spectrum. Given the large decrease in prevalence and the significant increase in associated bother when frequency exceeds once per night, we recommend that the definition of “increased nighttime frequency” be linked to nocturia occurring 2 or more times during sleeping hours. The use of this definition of “increased nighttime frequency” would allow comparisons with “increased daytime frequency,” and would incorporate bother symptoms not captured by current ICS definition of nocturia. Similarly, the use of a definition of “increased daytime frequency” that incorporates both frequency of voids and associated bother would incorporate voiding frequency not captured by the current ICS definition of “increased daytime frequency.” Some may argue that a definition of increased daytime or nighttime frequency that is met by nearly one third of the population is too broad, and thereby encourage treatment of those who exhibit only slight deviation from normal. However, numerous conditions, including pelvic floor disorders and obesity, are prevalent in approximately one third of the adult population and are not considered to be overly broad in their definitions. We suggest that the proposed definitions are far more restrictive than those currently recommended by the ICS.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH, NICHD R01 HD41113-01A1.

Footnotes

Location of study: Southern California

Presentation: This paper was presented at the annual American Urogynecologic Society Meeting September 4-6, 2008 in Chicago IL and at the International Continence Society meeting October 20-24, 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. discussion 1314–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Bhattacharyya SK, Thompson CL, Dhawan R, Versi E. The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health-related quality of life and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int. 2003;92:948–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Payne C, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. The impact of urinary urgency and frequency on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: results from a national community survey. Value Health. 2004;7(4):455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg RP, Lobel RW, Sand PK. The urinary tract in pregnancy. In: Bent AEODR, Cundif CW, Swift SE, editors. Ostergard’s urogynecology and pelvic floor dysfunction. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homma Y. Lower urinary tract symptomatology: Its definition and confusion. Int J Urol. 2008;15:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Nager CW, Luber KM. Parity, mode of delivery, and pelvic floor disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1253–60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218096.54169.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Buckwalter JG, Burchette RJ, Nager CW, Luber KM. Epidemiology of prolapse and incontinence questionnaire: validation of a new epidemiologic survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:272–84. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Burchette RJ, Luber KM, Nager CW, Buckwalter JG. The use of Visual Analog Scale in urogynecologic research: a psychometric evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons M, Tissot W, Cardozo L, Diokno A, Amundsen CL, Coats AC. Normative bladder diary measurements: night versus day. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:465–73. doi: 10.1002/nau.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siltberg H, Larsson G, Victor A. Frequency/volume chart: the basic tool for investigating urinary symptoms. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1997;166:24–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinnock C, Marshall VR. Troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms in the community: a prevalence study. Med J Aust. 1997;167:72–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGrother CW, Donaldson MM, Shaw C, et al. Storage symptoms of the bladder: prevalence, incidence and need for services in the UK. BJU Int. 2004;93:763–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein L, Brubaker L, Kenton K, Kramer H, Shott S, FitzGerald MP. Prevalence and impact of nocturia in a urogynecologic population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1049–52. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiske J, Scarpero HM, Xue X, Nitti VW. Degree of bother caused by nocturia in women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:130–3. doi: 10.1002/nau.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekundayo OJ, Markland A, Lefante C, et al. Association of diuretic use and overactive bladder syndrome in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.05.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird ET, Parker BD, Kim HS, et al. Caffeine ingestion and lower urinary tract symptoms in healthy volunteers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(7):611–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herschorn S, Gajewski J, Schulz J, et al. A population-based study of urinary symptoms and incontinence: the Canadian Urinary Bladder Survey. BJU Int. 2008 Jan;101(1):52–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald MP, Litman HJ, Link CL, McKinlay JB. The association of nocturia with cardiac disease, diabetes, body mass index, age and diuretic use: results from the BACH survey. J Urol. 2007;177:1385–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chartier-Kastler E, Robain G, Mozer P, Ruffion A. [Lower urinary tract dysfunction and diabetes mellitus] Prog Urol. 2007;17:371–8. doi: 10.1016/s1166-7087(07)92332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowenstein L, Kenton K, Brubaker L, et al. The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea, nocturia, and daytime overactive bladder syndrome in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:598e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]