Abstract

Primary care physicians, pediatricians, and psychiatrists account for approximately 80 percent of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatments prescribed in the United States. Selection of short-acting versus long-acting ADHD treatment varies by specialty with long-acting agents representing 56 percent of primary care prescriptions, 64 percent of psychiatrist prescriptions, and 79 percent of pediatric prescriptions. There appears to be a correlation between short-acting versus long-acting treatment selection and age, with long-acting agents accounting for 78 percent of prescriptions for pediatric patients (age 0–17) but only 49 percent of prescriptions for adults (patients aged 18+). A discussion of data is included.

Keywords: ADHD medication, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, long-acting formulation, short-acting formulation, stimulant, prescription

Introduction

In this article, we explore use of long-acting versus short-acting treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by primary care physicians, pediatricians, and psychiatrists. Variation in treatment selection by patient age is also investigated.

Methods

We obtained data on total retail prescriptions for ADHD medications in March, April, and May 2008 from Verispan’s Vector One National (VONA), which captures nearly half of all prescription activity in the US. Individual products were classified as short acting, medium acting, or long acting as follows:

Short acting: amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall), dextroamphetamine sulfate (Dexodrine, Dextrostat), dexmethylphenidate (Focalin), methamphetamine (Desoxyn), and methylphenidate or MPH (Methylin, Ritalin)

Medium acting: methylphenidate sustained release (Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR)

Long acting: amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall XR), methylphenidate (Concerta), methylphenidate (Daytrana), d-amphetamine sulfate (Dexedrine Spansules), dexmethylphenidate (Focalin XR), atomoxetine (Strattera), and lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse).

Results

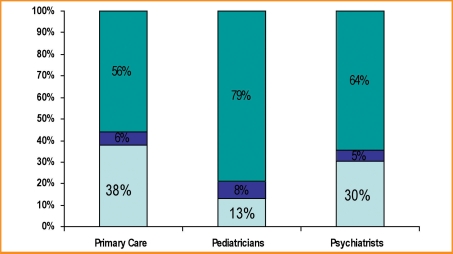

In 2007, almost seven million Americans filled at least one prescription for an ADHD therapy. Approximately 80 percent of therapies prescribed were written by primary care physicians (21%), pediatricians (28%), or psychiatrists (30%). Figure 1 displays short-acting versus medium-acting versus long-acting ADHD treatments prescribed by physician specialty. As seen in Figure 1, selection of short-acting versus long-acting ADHD treatment varies by specialty with long-acting agents representing 56 percent of primary care prescriptions, 64 percent of psychiatrist prescriptions, and 79 percent of pediatric prescriptions.

FIGURE 1.

Short-acting vs. medium-acting vs. long-acting ADHD therapies prescribed by specialty

Source: Verispan VONA, ADHD Therapies, March, April, May 2008.

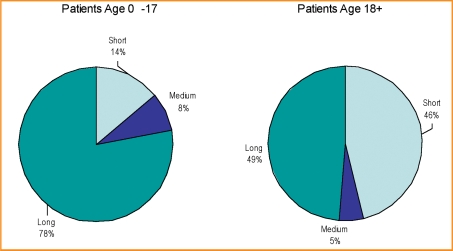

We examined the data further to determine whether there were any differences in use of short-acting versus long-acting ADHD treatments by patient age. The data presented in Figure 2 show that there does appear to be a difference in long-acting therapy use among pediatric and adult patients. Long-acting agents account for 78 percent of ADHD prescriptions in pediatric patients ages 0 to 17 years, but only 49 percent of adult ADHD prescriptions.

FIGURE 2.

Short-acting vs. medium-acting vs. long-acting ADHD therapies prescribed by patient age

Source: Verispan VONA, ADHD Therapies, March, April, May 2008.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan News Service; [18 December 2007.]. Overall, illicit drug use by American teens continues gradual decline in 2007. www.monitoringthefuture.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2005, Vol II, College Students and Adults ages 19–45. NIH. Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teter CJ, McCabe SE, LaGrange K, et al. Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2006261501–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilens TE, Gignac M, Swezey A, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 200645408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams RJ, Goodale LA, Shay-Fiddler MA, et al. Methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine abuse in substance-abusing adolescents. Am J Addict. 200413381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson J, Gupta S, Lam A, et al. Development of a new once-a-day formulation of methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: proof-of-concept and proof-of-product studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 200360204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Ciccone PE, et al. PET study examining pharmacokinetics, detection and likeability, and dopamine transporter receptor occupancy of short- and long-acting oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry. 2006163387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kollins SH, Rush CR, Pazzaglia PJ, et al. Comparison of acute behavioral effects of sustained-release and immediate-release methylphenidate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 19986367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasinski DR, Krishnan S. Human pharmacology of intravenous lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: abuse liability in adult stimulant abusers. J Psychopharmacol. 2008 Jul 17; doi: 10.1177/0269881108093841. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollins SH.A qualitative review of issues arising in the use of psychostimulant medications in patients with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr Med Res Opin 200824(5)1345–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capone NM, McDonnell T, Buse J, Kochhar A. Persistence with common pharmacologic treatments for ADHD.. Poster presented at: Annual International Conference of Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; October 27, 2005; Dallas, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisler RH.Review of long-acting stimulants in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 20078(6)745–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Dupaul GI, Bush T.Driving in young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: knowledge, performance, adverse outcomes, and the role of executive functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 200285655–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]