Abstract

Two genes have a synthetically lethal relationship when the silencing or inhibiting of 1 gene is only lethal in the context of a mutation or activation of the second gene. This situation offers an attractive therapeutic strategy, as inhibition of such a gene will only trigger cell death in tumor cells with an activated second oncogene but spare normal cells without activation of the second oncogene. Here we present evidence that CDK2 is synthetically lethal to neuroblastoma cells with MYCN amplification and over-expression. Neuroblastomas are childhood tumors with an often lethal outcome. Twenty percent of the tumors have MYCN amplification, and these tumors are ultimately refractory to any therapy. Targeted silencing of CDK2 by 3 RNA interference techniques induced apoptosis in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines, but not in MYCN single copy cells. Silencing of MYCN abrogated this apoptotic response in MYCN-amplified cells. Inversely, silencing of CDK2 in MYCN single copy cells did not trigger apoptosis, unless a MYCN transgene was activated. The MYCN induced apoptosis after CDK2 silencing was accompanied by nuclear stabilization of P53, and mRNA profiling showed up-regulation of P53 target genes. Silencing of P53 rescued the cells from MYCN-driven apoptosis. The synthetic lethality of CDK2 silencing in MYCN activated neuroblastoma cells can also be triggered by inhibition of CDK2 with a small molecule drug. Treatment of neuroblastoma cells with roscovitine, a CDK inhibitor, at clinically achievable concentrations induced MYCN-dependent apoptosis. The synthetically lethal relationship between CDK2 and MYCN indicates CDK2 inhibitors as potential MYCN-selective cancer therapeutics.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, synthetic lethal

Two genes are considered to be “synthetically lethal” if mutation of either gene alone is compatible with viability but simultaneous mutation of both genes causes death. This mechanism is best described for loss of function genes but also exits for gain of function genes. For example gene A can become essential for survival if gene B is over-expressed. This mechanism is potentially very attractive for the development of targeted anti cancer compounds that could specifically kill tumor cells while leaving normal cells alive (1–3). However, examples of synthetic lethal oncogenes in human tumors are hardly documented.

Neuroblastomas are embryonal tumors that originate from the developing sympathetic nervous system, and although neuroblastomas have a low incidence, they are the second cause of cancer related deaths in children (4, 5). The MYCN gene is amplified in 20–30% of neuroblastoma tumors and amplification strongly correlates with a bad prognosis. MYC genes are potent oncogenes that drive unrestrained cell growth and proliferation. They function as transcription factors that cause up-regulation or repression of genes involved in a variety of oncogenetic pathways. Recently MYC genes were also shown to control protein expression through mRNA translation and to directly regulate DNA replication (6–9). Apart from the function in oncogenesis, MYC genes have also been described to induce apoptosis if over-expressed in non MYC-amplified cells (10). This could indicate that the amplification of the MYC oncogenes requires a specific genetic background and that there could be synthetic lethal relations with other (onco)genes.

Cell cycle aberrations occur in all tumors and many targeted compounds inhibiting specific cell cycle kinases have been developed (11, 12). These efforts were based on the idea that the targeting of aberrant cell cycle checkpoints in cancer cells could lead to tumor growth inhibition and cell death (13). Several studies have recently shown that most cell cycle kinases are not essential for cell survival in vitro and in vivo (14). Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) was thought to be a crucial regulator of S-phase progression and was therefore evaluated as an anticancer drug target. Tetsu et al. however showed that CDK2 inhibition in several cancer cell types did not result in cell death, and Santamaria et al. showed that genetic ablation of CDK2 in mice could be compensated for by CDK1 (15, 16). These findings severely reduced optimism about CDK2 as therapeutic target.

Several cell cycle aberrations involving G1-regulating genes have been identified in neuroblastomas. Cyclin D1 and CDK4 gene amplifications occur at a low frequency, and a CDK6 mutation that inactivates p16-binding has been found (17–19). Cyclin D1 was found to be extremely over-expressed in about 75% of neuroblastoma tumors. Inhibition of the G1 regulating genes CDK4 or cyclin D1 in neuroblastoma cell lines resulted in restoration of the G1 checkpoint and subsequent neuronal differentiation (20). The absence of an apoptotic response made these G1 regulating genes less attractive as a therapeutic target.

In this paper, we show that inhibition of the next step of the cell cycle which is controlled by CDK2 results in massive cell death. This is in clear contrast with the previous findings of redundancy of CDK2. Inhibiting CDK2 using various siRNA based techniques showed an apoptotic response in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines and not in MYCN single copy cells. We could show a synthetically lethal relationship in which CDK2 silencing only results in cell death in the presence of MYCN. This lethal response is depending on functional p53. We show that this MYCN-dependent, P53-mediated apoptosis can also be induced by a CDK2-inhibiting small molecule.

Results

Silencing of CDK2 Is Lethal to MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma Cells.

To identify new drug targets in the cell cycle, we analyzed the mRNA expression pattern of cell cycle regulating genes in 88 neuroblastoma tumors. High CDK2 expression was strongly correlated with a bad prognosis (Fig. S1A). To evaluate CDK2 as a potential drug target, we silenced CDK2 expression in human neuroblastoma cell lines by transient siRNA. Surprisingly, CDK2 knock-down resulted in a strong induction of apoptosis in 3 MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell lines, while leaving 1 MYCN single copy neuroblastoma cell line and exponentially growing fibroblasts unaffected (Fig. 1A). To further analyze the effects of CDK2 knock-down, we introduced an inducible shRNA construct into the neuroblastoma cell line IMR32 (targeting another sequence in the CDK2-coding region) and performed time-course analysis. Induction of CDK2 shRNA resulted in a decrease in CDK2-specific pRb phosphorylation, followed by PARP and caspase 3 cleavage (Fig. 1B). An E2F reporter construct revealed a strong reduction of E2F activity (Fig. 1C). FACS analysis showed a G1 arrest after 48 h followed by an increase in subG1 fraction, indicative of apoptosis (Fig. S1B). Cell counting after induction of CDK2 shRNA confirmed progressive cell death at 48, 72, and 96 h after CDK2 silencing (Fig. 1D), eventually leading to 100% cell death after 6 days. We used a lentiviral-mediated shRNA targeting a third CDK2 mRNA sequence, but now located in the non-coding 3′UTR. Again CDK2 silencing in IMR32 resulted in PARP and caspase 3 cleavage indicating apoptosis (Fig. 1E). To rescue this phenotype, we ectopically over-expressed the coding region of CDK2 in the neuroblastoma cell line IMR32. CDK2 silencing in this cell line using the lentiviral-encoded shRNA targeting the 3′UTR, silenced the endogenous CDK2 but not the ectopic CDK2 (Fig. S1 C and D). These cells did not show an apoptotic response, thus excluding off-target effects of the CDK2 shRNA (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1E). Our findings are in clear contrast with previous reports on the lack of apoptosis after CDK2 inhibition (16). We hypothesized that the apoptotic response after CDK2 silencing depends on the genetic background of the cell system, as we observed apoptosis only in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells and not in a MYCN single copy neuroblastoma cell line and exponentially growing fibroblasts (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

CDK2 inhibition causes apoptosis in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells. (A) Three MYCN amplified neuroblastoma cell lines, 1 MYCN single copy cell line (s.c.) and exponentially growing fibroblasts were transfected with 21-bp double strand siRNA against CDK2 or GFP as control. Samples were harvested at 48 h and immunoblotted for CDK2, PARP, and β-actin. The PARP antibody recognizes total and cleaved PARP (lower band). Cleavage of PARP indicates activation of the apoptotic pathway. Light microscopy pictures were taken just before harvesting the cells. (B) The neuroblastoma cell line IMR32 was transfected with a pcDNA6/TR vector and a vector containing CDK2 shRNA under a Tet operator-controlled CMV promoter generating the inducible cell line IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh. Doxycycline was added at time point 0 to induce CDK2 shRNA expression and silence CDK2. Cells were harvested at various time points and immunoblotted for CDK2, threonine 821-phosphorylated pRb, PARP, cleaved caspase 3, and β-actin. Cleavage of PARP and caspase 3 indicates activation of the apoptotic pathway. (C) A firefly luciferase vector containing 6 E2F-binding sites was transfected together with a renilla luciferase vector in IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh. After transfection, doxycycline was added. Control samples were not treated. Dual-luciferase assays were performed after 48 and 72 h to measure the relative E2F activity. (D) IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh and the IMR32-pcDNA6 from which this cell line was derived were grown in the presence or absence of doxycycline. Cells were harvested at various time points and counted using a Coulter counter. (E) IMR32 cells were infected with the lentiviral vector encoding either CDK2 shRNA or the control shRNA and harvested at various time points after infection. Samples were immunoblotted for CDK2, PARP, cleaved caspase 3, and β-actin. (F) A CDK2 cDNA expression vector and an empty vector were transfected in IMR32. Clones were isolated using neomycin selection and 1 empty vector control clone and 2 clones expressing ectopic CDK2 were selected for further analysis. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of lentiviral CDK2 shRNA. Nontreated (NT) samples were also included. Samples were immunoblotted for CDK2, PARP, and β-actin.

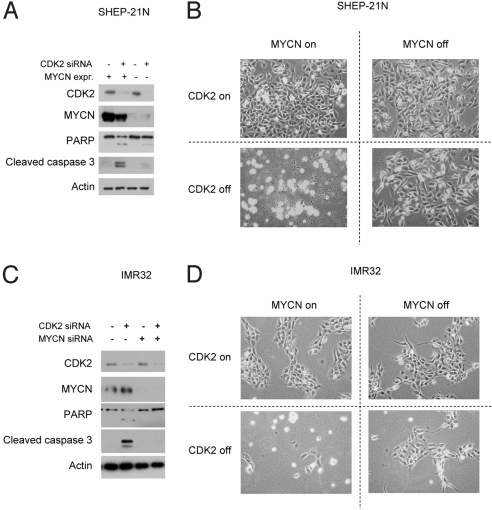

Apoptosis After CDK2 Inhibition is Dependent on MYCN Over-Expression.

To test whether apoptosis induced by CDK2 inhibition is MYCN-dependent, we used SHEP-21N, a MYCN single copy neuroblastoma cell line with a MYCN transgene that can be repressed by the addition of tetracyclin (Tet-off system). CDK2 silencing by transient CDK2 siRNA induced apoptosis when MYCN was expressed but not when MYCN was silent (Fig. 2 A and B). To further validate the MYCN-dependency, we tested this in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells (IMR32). Silencing of CDK2 using transient siRNA in IMR32 resulted in massive apoptosis that could be rescued by silencing of MYCN with transient siRNA (Fig. 2 C and D). These findings show that apoptosis after CDK2 silencing is indeed dependent on MYCN over-expression.

Fig. 2.

Apoptosis after CDK2 inhibition in neuroblastoma is dependent on MYCN over-expression. (A) SHEP-21N, a neuroblastoma cell line containing MYCN under a Tet repressor, was cultured with and without tetracycline for 3 days and then re-plated on 6-well plates at a density of 6 × 104 cells per well and treated with CDK2 siRNA or a control siRNA. Cells were harvested 48 h after siRNA treatment and immunoblotted for CDK2, MYCN, PARP, cleaved caspase 3, and β-actin. (B) Light microscopy pictures were taken just before harvesting the cells. Samples with MYCN on and CDK2 off settings showed a >94% reduction in cell density compared with all control samples. (C) IMR32, a neuroblastoma cell line with MYCN amplification, was seeded on 6-cm plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per plate and treated with control siRNA, CDK2 siRNA, MYCN siRNA, or combination of MYCN and CDK2 siRNA. Cells were harvested after 48 h and immunoblotted for CDK2, MYCN, PARP, cleaved caspase 3, and β-actin. (D) Light microscopy pictures were taken just before harvesting the cells. Samples with MYCN on and CDK2 off settings sowed a >85% reduction in cell density compared with all control samples.

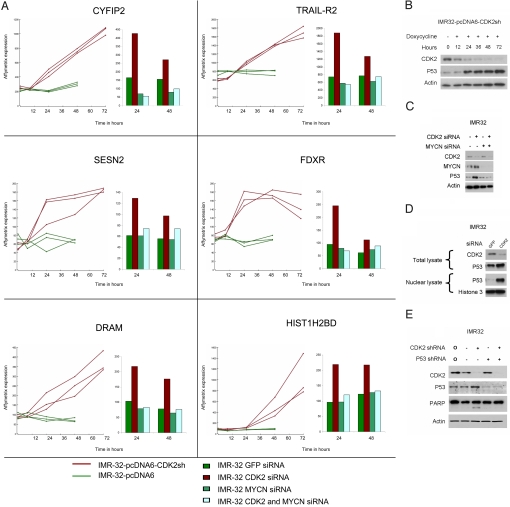

Apoptotic Induction After CDK2 Silencing Is Mediated by the P53 Pathway.

To identify genes involved in this apoptotic response we generated Affymetrix mRNA expression profiles of IMR32 at various time points after inducible silencing of CDK2. In addition, we generated Affymetrix profiles of IMR32 after treatment with transient CDK2 siRNA alone, MYCN siRNA alone, or a combination of CDK2 and MYCN siRNA. We selected for genes that were up-regulated after CDK2 silencing but not after combined CDK2 and MYCN silencing (see Methods for selection procedure). These stringent criteria identified genes involved in Rac GTPase signaling (CYFIP2), peroxide signaling (SESN2), autophagy (DRAM), apoptotic signaling (TRAIL-R2, FDXR), and 1 a member of the histone H2B family (HIST1H2B). Strikingly, 5 out of 6 of the most strongly regulated genes are established direct transcriptional target genes of P53 (Fig. 3A). This suggests an involvement of P53 in the apoptotic response (21–25). P53 mRNA levels are constant (Affymetrix) but the P53 protein levels increase after inducible and transient CDK2 silencing in MYCN over-expressing cells (Fig. 3 B and C). This indicates that P53 protein levels are up-regulated by stabilization. In addition, P53 showed nuclear translocation after CDK2 silencing (Fig. 3D). Finally, to analyze P53 dependency in the apoptotic response, we used lentiviral silencing of P53 and CDK2. Silencing of P53 indeed prevents PARP cleavage in cells with CDK2 silencing (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis after CDK2 silencing in MYCN-amplified cell is P53-mediated. (A) IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh with doxycycline and IMR32-pcDNA6 were harvested for RNA isolation at various time points after the addition of doxycycline. Also, transient siRNA experiments were performed in IMR32 using GFP siRNA, CDK2 siRNA, MYCN siRNA, or CDK2 and MYCN siRNA. RNA was isolated at 24 and 48 h after transfection. Affymetrix microarray profiling was performed for both the inducible shRNA time-course experiments and the transient siRNA experiments. Affymetrix expression levels are shown for the 6 most strongly regulated genes. (See Materials and Methods for the selection procedure.) (B) IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh was seeded on 6-cm plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per plate and treated with doxycycline to induce CDK2 shRNA. Cells were harvested at various time points. Samples were immunoblotted for CDK2, P53, and β-actin. (C) IMR32 was seeded on 6-cm plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per plate and treated with control siRNA, CDK2 siRNA, MYCN siRNA, or a combination of MYCN and CDK2 siRNA. Cells were harvested after 48 h and immunoblotted for CDK2, MYCN, P53, and β-actin. (D) IMR32 was seeded as described under Fig. 3C and treated with CDK2 siRNA or GFP siRNA and harvested 48 h after transfection. Total lysates and nuclear lysates were isolated. Total lysates were stained with CDK2 and P53 and the nuclear lysates with P53 and histone H3 for loading control. (E) IMR32 was seeded on 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and infected with a lentiviral vector encoding CDK2 shRNA, P53 shRNA, or both shRNAs. Non-coding SHC002 control shRNA was added to experiments with CDK2 or P53 shRNA only and in the control samples to equal the amount of shRNA in each sample. Also a non-transfected control was included (o). Protein was harvested after 48 h and immunoblotted for CDK2, P53, PARP, and β-actin.

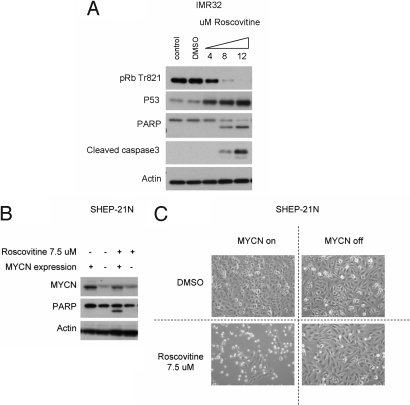

The CDK2-Targeting Drug Roscovitine Induces P53-Dependent Apoptosis in MYCN-Amplified Cells.

To extend these findings to clinically applicable compounds, we used a CDK2-inhibiting small molecule. Roscovitine is a CDK inhibitor with a relatively high affinity for the CDK2 ATP-binding pocket and IC50 levels in micromolar range (26, 27). In the MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cell line IMR32, roscovitine causes an inhibition of CDK2-specific pRb phosphorylation and a strong apoptotic response followed by P53 stabilization and PARP and caspase 3 cleavage (Fig. 4A). The fast response (6 h after exposure to the compounds) probably reflects the direct effect of the small molecules on the CDK2 kinase activity compared with the slower decrease of CDK2 protein levels after siRNA-mediated silencing. We determined roscovitine LC50 levels for IMR32 and SHEP-21N (respectively 3.0 μM and 7.5 μM) and used those concentrations to compare the sensitivity in the MYCN on and off settings. In both cell lines, roscovitine induced cell death when MYCN was expressed but not when MYCN was silenced (Fig. 4 C and D and Fig. S4 A and B).

Fig. 4.

The CDK2-inhibiting small molecule roscovitine induces P53-mediated apoptosis in cells over-expressing MYCN. (A) IMR32 was seeded in on 6-cm plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per plate and treated with increasing concentrations of roscovitine. Cells were harvested 6 h after treatment. Samples were immunoblotted for threonine 821 phosphorylated pRb, P53, PARP, cleaved caspase 3, and β-actin. (B) SHEP-21-N, a neuroblastoma cell line containing MYCN under a Tet repressor, was cultured with or without tetracycline for 3 days and then re-plated on 6-cm plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per plate. After 24 h, roscovitine was added to an end concentration of 7.5 μM. Twenty-four hours after start of treatment cells were harvested and immunoblotted for MYCN, PARP, and β-actin. (C) Light microscopy pictures were taken just before harvesting the cells. The sample with MYCN expression and roscovitine treatment showed a decrease of >91% in cell density compared with all control samples.

Discussion

Despite previous reports of redundancy of CDK2 in various tumor and non-malignant cell systems, we show a strong dependence on CDK2 in the subset of MYCN over-expressing neuroblastomas. Off-target RNA interference effects cannot explain these findings as we have used 3 different RNAi techniques with different target sequences that gave the same results and we could rescue the phenotype by over-expressing CDK2. Moreover, Affymetrix profiling of the time course of IMR32 cells with inducible CDK2 shRNA showed no up-regulation of genes involved in the IFN response (28). Finally, a CDK2-inhibiting small molecule gives similar phenotypic effects. We show that these findings are the result of a synthetically lethal relationship between CDK2 and over-expressed MYCN. A search for the etiology of the apoptotic response revealed a strong induction of P53 at various levels, but we can not exclude involvement of other signal transduction routes. It seems unlikely that this apoptotic response involves E2F, as down-regulation of E2F transcriptional activity after CDK4 or cyclin D1 silencing in neuroblastoma cell lines does not result in apoptosis but leads to neuronal differentiation (20). We did not test whether cells with over-expression of the MYC (c-Myc) oncogene show comparable sensitivity for CDK2 inhibition, but Goga et al. showed that MYC-over-expressing cells are more sensitive to CDK1/2 inhibitors (29). This suggests that the synthetically lethal relationship between CDK2 and MYCN described here could also exist between CDK2 and MYC.

Our results suggest that CDK2 inhibitors might be potential MYCN-selective cancer therapeutics in a p53 wild-type background. Most neuroblastoma primary tumors have intact and functional P53 (30, 31). The MYCN gene is amplified in 20–25% of the tumors and relates to an extremely poor prognosis. These 2 characteristics make neuroblastoma tumors good candidates for in vivo validation and subsequent clinical trials with small molecule CDK2 inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Patient Material and Cell Lines.

The neuroblastoma tumor panel used for Affymetrix Microarray analysis contains 88 neuroblastoma samples. All samples were derived from primary tumors of untreated patients. Material was obtained during surgery and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 mM L-glutamine, 10 U/mL penicillin, and 10 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2. For primary references of these cell lines, see Cheng et al. (32). The IMR32 subclones with over-expression of CDK2 and the empty vector controls were generated by transfecting 4 μg pCMV-neo-Bam or pCMV-neo-Bam CDK2 expression vector (Addgene) (33) using Lipofectamin 2000 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Clones were selected using 300 μg/mL Neomycine.

RNA Interference.

The synthetic siRNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Eurogentec. siRNAs were targeting CDK2 on nucleotides 401–419 in NM_001798.2 and MYCN on nucleotides 348–366 at NM_005378 (Natinal Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank) Previously designed siRNA directed against GFP was used as a negative control (sense sequence: GACCCGCGCCGAGGUGAAGTT). Neuroblastoma cell lines were cultured for 24 h in 6-cm plates and transfected with 5.5 μg siRNA using Lipofectamine according to manufacturer's protocol. The lentiviral shRNAs were obtained from Sigma (MISSION shRNA Lentiviral Transduction Particles). IMR32 cells were counted and 100,000 cells were plated in 6-cm wells in 2 mL culture medium. The culture medium was changed after 16 h, and the cells were infected with either the shCDK2-lentivirus (MISSION shRNA TRCN0000000587) the P53 shRNA (MISSION shRNA TRCN0000003755) or the control lentivirus (MISSION Non-Target shRNA Control SHC002). Virus concentrations were determined using a p24 ELISA. The IMR32 clone capable of inducible CDK2 shRNA expression was generated in a step-wise process. First, IMR32 cells were transfected with the pcDNA6/TR vector (Invitrogen), encoding the tetracycline/doxycycline repressor behind a constitutive CMV promoter, using Lipofectamine 2000. Clones were selected using 5 μg/mL blasticidin-S (Invitrogen), resulting in the isolation of IMR32-pcDNA6. The CDK2 shRNA expression constructs were prepared as follows: oligonucleotides targeting CDK2 on nucleotides 546–566 in NM_001798.2 (GenBank) were annealed and ligated into pTER restricted with BglII and HindIII as described (34, 35), creating pTER/CDK2. This construct was used for transfection of IMR32-pcDNA6 using Lipofectamine 2000. Clones were again selected using 5 μg/mL blasticidin-S and 10 μg/mL zeocine, resulting in the isolation of IMR32-pcDNA6-CDK2sh. For induction of the shRNA expression vector, doxycycline was added to the culture medium to a concentration of 100 ng/mL.

Compounds.

Roscovitine was obtained from Sigma and diluted to a concentration of 30 mM in DMSO. Cells were treated with various concentrations of roscovitine with a constant DMSO concentration of 0.5%.

Western Blotting.

The neuroblastoma cell lines were harvested on ice and washed twice with PBS. Cells were lysed in a 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, buffer. Protein was quantified with RC-DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Loading was controlled by Bio-Rad Coomassie staining of a reference SDS/PAGE gel. Lysates were separated on a 10% SDS/PAGE gel and electro-blotted on a transfer membrane (Millipore). Blocking and incubation were performed using standard procedures (20). The following antibodies were used as primary antibodies: CDK2 clone 55 mouse monoclonal (BD Bioscience), PARP clone 4C10–5 mouse monoclonal (BD PharMingen), pRb (pT821) (Biosource), P53 clone DO-7 mouse monoclonal (Labvision), Cleaved caspase 3 (Asp-175) rabbit polyclonal (Cell Signaling Technology), MYCN mouse monoclonal (PharMingen), histone H3 mouse monoclonal (Upstate), and actin C2 mouse monoclonal (Santa Cruz). After incubation with a secondary sheep anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked antibody (Amersham), proteins were visualized using an ECL detection kit (Amersham). Antibodies were stripped from the membrane using a 2% SDS, 100 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.7 buffer.

Cell Counting and FACS Analysis.

All cell counting experiments were performed twice. Cells were collected by trypsinization and diluted in 2 mL medium. Two samples of 100 μL of this medium were diluted in 100 μL TritonX-100/saponine and 10 mL isotone II was added. Duplicate counting of each sample was performed using a coulter counter (Beckman Coulter). For FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorter) analysis cells were grown for 24 h in 6-well plates and then transfected with siRNA as described before. At the indicated time-point after transfection, cells were lysed with a 3.4 mM Tri-sodiumcitrate, 0.1% Triton X-100 solution containing 50 μg/μL of propidium iodide. After a 1-h incubation, the DNA content of the nuclei was analyzed using a FACS. A total of 30,000 nuclei per sample were counted. The cell cycle distribution and apoptotic sub G1 fraction was determined using WinMDI version 2.8.

Transactivation Assays.

The following luciferase constructs were used in the transactivation assays: pGL3 TATAbasic-6xE2F [pGL3 containing a TATA box and 6 E2F-binding sites was previous tested for E2F selectivity and was a kind gift of R. Bernards, The Dutch Cancer Institute (36)] and pRL-CMV (Renilla luciferase vector under CMV promoter). Cells were cultured for 24 h in 6-well plates, and transfections were conducted using Lipofectamine according to manufacturer's protocol. One microgram pGL3TATAbasic-6xE2F vector was transfected together with 0.8 μg pRL-CMV vector. Dual luciferase assays were performed after 48 and 72 h using the Promega dual-luciferase reporter assay system. For each assay, 3 separate experiments were performed.

RNA Isolation and Affymetrix Microarray Analysis.

Total RNA of neuroblastoma cell lines and tumors was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration was determined using the NanoDrop ND-1000 and quality was determined using the RNA 6000 Nano assay on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). For Affymetrix Microarray analysis, fragmentation of RNA, labeling, hybridization to HG-U133 Plus 2.0 microarrays, and scanning were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol (Affymetrix Inc.). The expression data were normalized with the MAS5.0 algorithm within the GCOS program of Affymetrix. Target intensity was set to 100 (α1 = 0.04 and α2 0.06). If more than 1 probe set was available for 1 gene, the probe set with the highest expression was selected, considering that the probe set was correctly located on the gene of interest. For the selection of genes involved in apoptosis after CDK2 silencing, we used the following procedure. First, genes were selected that showed a minimal expression of 100 (MASS 5.0) in at least 1 time point in all time courses and transient experiments. Next, genes were selected that were up-regulated at least 1 2log fold at time-point 48 compared with time point 0 in the biological triplicate of the inducible CDK2 shRNA experiments. Genes that were regulated more than 0.5 2log fold in the control time courses were excluded. These genes were further analyzed using the transient siRNA experiments. Genes were only included if they were up-regulated more than 1 2log fold at time point 24 in the CDK2 siRNA samples compared with the GFP control sample. Finally, genes were excluded if they were up-regulated more than 0.5 2log fold in the CDK2 and MYCN siRNA experiment.

Q-PCR.

1 μg of TRIzol isolated RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with 125 pM oligodT12 primers, 0.5 mM dNTPs, 2 mM MgCl2, RT-buffer (Invitrogen), and 100 U SuperScript II (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 25 μL. One microliter of this cDNA was used for Q-PCR. A fluorescence-based kinetic real-time PCR was performed using the real-time iCycler PCR platform (Bio-Rad) in combination with the intercalating fluorescent dye SYBR Green I. The IQ SYBR Green I Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The following primers were used: β-actin forward 5′-CCCAGCACAATGAAGATCAA-3′ and reverse 5′-ACATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGAC-3′; CDK2 coding sequence forward 5′-ACCAGCTCTTCCGGATCTTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATCCTGGAAGAAAGGGTGA-3′; CDK2 3′UTR forward 5′-CCCTTTCTTCCAGGATGTGA-3′ and reverse 5′-TGAGTCCAAATAGCCCAAGG-3′.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank J. Laoukili and E. Santo for helpful discussion, P.G. van Sluis and M. Indemans for Affymetrix microarray profiling, I. Ora for archiving and updating patient data and P.J. Molenaar and R. Volckmann for data processing. The work was supported by Stichting Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds, Stichting Kindergeneeskundig Kankeronderzoek, and Kinderen Kankervrij.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.H.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0901418106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kaelin WG., Jr The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartz SR, et al. Small interfering RNA screens reveal enhanced cisplatin cytotoxicity in tumor cells having both BRCA network and TP53 disruptions. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9377–9386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01229-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friend SH, Oliff A. Emerging uses for genomic information in drug discovery. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:125–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801083380211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–2120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Noesel MM, Versteeg R. Pediatric neuroblastomas: Genetic and epigenetic ‘danse macabre’. Gene. 2004;325:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boon K, et al. N-myc enhances the expression of a large set of genes functioning in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. EMBO J. 2001;20:1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole MD, Cowling VH. Transcription-independent functions of MYC: Regulation of translation and DNA replication. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:810–815. doi: 10.1038/nrm2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koppen A, et al. Direct regulation of the minichromosome maintenance complex by MYCN in neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2413–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel JH, Loboda AP, Showe MK, Showe LC, McMahon SB. Analysis of genomic targets reveals complex functions of MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:562–568. doi: 10.1038/nrc1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer N, Kim SS, Penn LZ. The Oscar-worthy role of Myc in apoptosis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: A critical decision in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:222–231. doi: 10.1038/35106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1770–1783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2699–2711. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santamaria D, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448:811–815. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Proliferation of cancer cells despite CDK2 inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Easton J, Wei T, Lahti JM, Kidd VJ. Disruption of the cyclin D/cyclin-dependent kinase/INK4/retinoblastoma protein regulatory pathway in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2624–2632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molenaar JJ, van SP, Boon K, Versteeg R, Caron HN. Rearrangements and increased expression of cyclin D1 (CCND1) in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:242–249. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Roy N, et al. Identification of two distinct chromosome 12-derived amplification units in neuroblastoma cell line NGP. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;82:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00034-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molenaar JJ, et al. Cyclin D1 and CDK4 activity contribute to the undifferentiated phenotype in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2599–2609. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson RS, Cho YJ, Stein S, Liang P. CYFIP2, a direct p53 target, is leptomycin-B sensitive. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:95–103. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu GS, et al. KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1997;17:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G, Chen X. The ferredoxin reductase gene is regulated by the p53 family and sensitizes cells to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:7195–7204. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerley-Hamilton JS, Pike AM, Hutchinson JA, Freemantle SJ, Spinella MJ. The direct p53 target gene, FLJ11259/DRAM, is a member of a novel family of transmembrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1769:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabian MA, et al. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meijer L, et al. Biochemical and cellular effects of roscovitine, a potent and selective inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases cdc2, cdk2, and cdk5. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bridge AJ, Pebernard S, Ducraux A, Nicoulaz AL, Iggo R. Induction of an interferon response by RNAi vectors in mammalian cells. Nat Genet. 2003;34:263–264. doi: 10.1038/ng1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goga A, Yang D, Tward AD, Morgan DO, Bishop JM. Inhibition of CDK1 as a potential therapy for tumors over-expressing MYC. Nat Med. 2007;13:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nm1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, et al. p53 is nuclear and functional in both undifferentiated and differentiated neuroblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2685–2696. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tweddle DA, et al. The p53 pathway and its inactivation in neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2003;197:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng NC, et al. Lack of class I HLA expression in neuroblastoma is associated with high N-myc expression and hypomethylation due to loss of the MEMO-1 locus. Oncogene. 1996;13:1737–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Heuvel S, Harlow E. Distinct roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in cell cycle control. Science. 1993;262:2050–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.8266103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Wetering M, et al. Specific inhibition of gene expression using a stably integrated, inducible small-interfering-RNA vector. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:609–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu B, Geerts D, Qian K, Zhang H, Zhu G. Myeloid ecotropic viral integration site 1 (MEIS) 1 involvement in embryonic implantation. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1394–1406. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukas J, et al. Cyclin E-induced S phase without activation of the pRb/E2F pathway. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1479–1492. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.