Abstract

As a budding yeast cell elongates toward its mating partner, cytoplasmic microtubules connect the nucleus to the cell cortex at the growth tip. The Kar3 kinesin-like motor protein is then thought to stimulate plus-end depolymerization of these microtubules, thus drawing the nucleus closer to the site where cell fusion and karyogamy will occur. Here, we show that pheromone stimulates a microtubule-independent interaction between Kar3 and the mating-specific Gα protein Gpa1 and that Gpa1 affects both microtubule orientation and cortical contact. The membrane localization of Gpa1 was found to polarize early in the mating response, at about the same time that the microtubules begin to attach to the incipient growth site. In the absence of Gpa1, microtubules lose contact with the cortex upon shrinking and Kar3 is improperly localized, suggesting that Gpa1 is a cortical anchor for Kar3. We infer that Gpa1 serves as a positional determinant for Kar3-bound microtubule plus ends during mating.

INTRODUCTION

The regulation of the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons by external stimuli is essential to many fundamental processes in eukaryotic cells, including chemotaxis, differentiation, morphogenesis, and secretion (Acuto and Cantrell, 2000; Musch, 2004; Affolter and Weijer, 2005; Bardwell, 2005). The mating reaction of the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is an excellent model with which to study signal-induced changes in cytoskeletal polarity and organelle position. During the haploid phase of their life cycle, yeast cells secrete peptide pheromones that transform vegetatively growing cells of opposite mating type into gametes. Preparatory to cellular and nuclear fusion, pheromone triggers the induction of mating-specific genes, cell cycle arrest, polarized growth toward the mating partner, and nuclear migration to the tip of the mating projection (Rose, 1996; Madden and Snyder, 1998; Bardwell, 2005).

The molecular mechanisms underlying transmission of the mating signal to the nucleus are well understood. Communication of the signal across the plasma membrane is mediated by a G protein-coupled receptor (Bardwell, 2005). When occupied by ligand, the pheromone receptors activate the pheromone-responsive Gα protein (Gpa1) via guanine nucleotide exchange and the subsequent dissociation of Gα-GTP from the Gβγ dimer. The signal is then transmitted by Gβγ through a Pak kinase and a scaffolding protein to a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade. Upon activation in the cytoplasm, the Fus3 MAP kinase accumulates in the nucleus (Choi et al., 1999; vanDrogen et al., 2001; Blackwell et al., 2003), where it induces mating-specific transcription and cell cycle arrest.

In addition to regulating transcription and cell proliferation, pheromone elicits directional responses: directed growth of the mating projection and movement of the nucleus into it (Rose, 1996; Madden and Snyder, 1998). In a mating mixture, a yeast cell determines the direction of the strongest source of pheromone and orients its axis of polarity toward the closest potential mating partner (Jackson and Hartwell, 1990). The first known step in this process is the spatial rearrangement of the pheromone receptor. In response to pheromone stimulation, the distribution of the receptor on the cell surface changes from uniform to a polarized crescent (Ayscough and Drubin, 1998). The βγ subunit of the associated G protein is an early positional determinant of the growth site (Butty et al., 1998; Nern and Arkowitz, 1999). Gβγ recruits Far1 from the nucleus and the Gβγ–Far1 complex competes with the bud site determinant Bud1 to specify where actin cables will be nucleated via Cdc42 and its effectors (Nern and Arkowitz, 1999). The pheromone-responsive Gα protein also influences actin polarity (Matheos et al., 2004), at least in part by recruiting active Fus3 to phosphorylate the formin Bni1, a member of the polarisome complex. Once the actin cables are polymerized and correctly oriented, a myosin motor protein, Myo2, moves vesicles containing plasma membrane and cell wall constituents, as well as many of the signaling molecules, to the growth site (Pruyne et al., 2004).

Nuclear migration depends on the dynamic instability of cytoplasmic microtubules that grow from the spindle pole body (SPB) and which attach the nucleus to the cortex at the tip of the mating projection, or shmoo (Rose, 1996; Maddox et al., 1999). A Myo2-Kar9-Bim1 complex transports the plus ends of these microtubules into the mating projection along the polarized actin cables (Hwang et al., 2003). In mating projections, there is typically a bundle of three to four cytoplasmic microtubules attached to the shmoo tip, as well as one to two free microtubules (Maddox et al., 1999). Both the free and attached microtubules grow and shrink periodically (Maddox et al., 1999, 2003). It has been proposed that polymerizing microtubules are connected to the cortex by Bim1 and Kar9 (Maddox et al., 2003). As these microtubules lengthen, the nucleus is pushed away from the shmoo tip. The nucleus is drawn toward the shmoo tip, in contrast, when the attached microtubules shorten (Maddox et al., 1999, 2003). This requires Kar3, a minus-end–directed kinesin-like motor protein, and one of its light chains, Cik1 (Maddox et al., 2003; Sproul et al., 2005). In response to pheromone stimulation, Kar3 and Cik1 localize to the plus ends of cytoplasmic microtubules in an interdependent manner (Page et al., 1994; Maddox et al., 2003). At the shmoo tip, Kar3-Cik1 is thought to promote the persistent depolymerization of the associated microtubules (Maddox et al., 2003; Sproul et al., 2005) and to maintain their cortical interaction as they shorten (Maddox et al., 2003). Thus, the nucleus is pulled to the site where cell fusion and karyogamy will occur. It is not known, however, how Kar3 is anchored to the shmoo tip, nor how pheromone regulates Kar3 function at the cortex.

Here, we show that the pheromone-responsive Gα protein, Gpa1, interacts with Kar3 and that it positions the plus ends of cytoplasmic microtubules at the cortex of the shmoo tip. Like Kar3, Gpa1 seems to promote the shrinkage of these microtubules while helping to maintain their cortical contact. Thus, Gpa1 may serve both to anchor Kar3 at the cortex and to stimulate its activity. Our data reveal a novel mechanism for communicating external signals to the microtubule cytoskeleton. Interestingly, Gα12/13 proteins in mouse embryonic fibroblasts have also been recently implicated in linking extracellular signals to microtubule dynamics and cell polarity, albeit via a distinct mechanism (Goulimari et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains and Culture Conditions

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All are derivatives of either strain BF264-15D (MATa bar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3112 trp1-1a ura3Δ) (Reed et al., 1985) or strain BY4741 (MATa GF554 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 BAR1) (Winzeler et al., 1999), with the exception of the gpa1ts strain and strain Y1870 in which Kar3 was hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged in situ (Manning et al., 1999). The gpa1ts allele was originally isolated in strain 381G, but it was backcrossed three times to BF264-15D to generate the strain used in this work. The Gpa1 overexpression/turn-off strain SLY168 was constructed by replacing the coding region of GPA1 with that of URA3 and integrating the GAL1EG43-GPA1 transcriptional fusion at the LEU2 locus by using YIplac128 (Gietz and Sugino, 1988). The GPA1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and GAL1-GPA1-GFP reporter strains were generated by transforming SLB126 and SLB127 (see below) into DSY296, a MATa/MATa gpa1Δ::URA3/gpa1Δ::URA3 strain derived from BF264-15D, sporulating the transformants, and isolating MATa GPA1-GFP (SLY111) and MATa GAL1-GPA1-GFP (SZY267) segregants. The complete deletion of KAR3 in SLY168 was generated by homologous recombination using the KanMX6 cassette polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified with flanking KAR3 sequence (Wach, 1996) to yield strain SLY370. All yeast manipulations were performed as described previously (Sherman et al., 1986).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Background | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLY111 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1Δ::URA3 YCplac111/GPA1-GFP | This study |

| SZY123 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY125 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ YCplac22/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY126 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1Δ::URA3 YIplac128/GAL1EG43-GPA1 YCplac22/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SLY168 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1Δ::URA3 YIplac128/GAL1EG43-GPA1 | Stone laboratory |

| SLY245 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ pRS316CG/GPA1-GFP | This study |

| SZY254 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ pbj1351/GFP-TUB1 | This study |

| SZY257 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ pRS316CG/GPA1-GFP | Stone laboratory |

| SZY267 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ YCplac22/GAL1-GPA1-GFP | Stone laboratory |

| SZY270 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ DSB132/GAL1-GPA1 YCplac22/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY274 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ gpa1Δ::URA3 YCPlac22/GPA1 | Stone laboratory |

| SSY370 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ kar3Δ::kan | This study |

| SZY136 | TBY101 | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1ts | Stone laboratory |

| SZY138 | BF264-15D | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ gpa1Δ::URA3 YCPlac22/GPA1 | Stone laboratory |

| SZY143 | TBY101 | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1ts pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | Stone laboratory |

| SZY145 | TBY101 | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a ura3Δ gpa1ts YCplac22/KAR3-GFP | Stone laboratory |

| SZY147 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Δ library |

| SZY148 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 kar3::kan | Δ library |

| SZY165 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY166 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 kar3::kan pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY169 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cik1::kan | Δ library |

| SZY172 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cik1::kan pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | This study |

| SZY190 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 GAL1-HO-URA3 | This study |

| SZY230 | BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 vik1::kan | This study |

| Y1870 | MATabar1Δ ade1 his2 leu2-3,112 trp1-1a, ura3Δ Kar3-HAT::URA3 | Manning et al. (1999) |

Plasmid Construction

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The key details of the newly constructed plasmids are described below. Recombinant DNA techniques were essentially as described by Ausubel et al. (1994). The GPA1 locus (−817 to 1420) was PCR amplified from a genomic template using the following primers: 5′-ACGCGTCGACAGAATGAATCTTCGTGCCTAG-3′, which contains a SalI site, and 5′-CGTAGCGGCCGCATATAATACCAATTTTTTTAAGGTTTTG-3′, which contains a NotI site. The Gpa1 PCR product was then subcloned into SalI-NotI-cut pRS316CG (Liu and Lindquist, 1999) to create the in-frame GPA1-GFP translational fusion pRS316CG/GPA1-GFP (SZB100). To change selectable markers, the SacI-SalI fragment containing GPA1-GFP in SZB100 was moved to YCplac111 (Gietz and Sugino, 1988), yielding YCplac111/GPA1-GFP (SLB126). The GAL1-GPA1-GFP reporter was created by PCR amplifying the GPA1-GFP fusion contained on YCplac111/GPA1-GFP (SLB126) using the following primers: 5′ GACTTTCTAGAATGGGGTGTACAGTGAGTACGC-3′, which contains a XbaI site, and 5′-GACTTCTGCAGTCATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCC-3′, which contains a PstI site. The PCR product was then subcloned into XbaI-PstI-cut pZWB159 (Blackwell et al., 2003) to generate SLB253. The KAR3 locus (1-2247) was PCR amplified from a genomic template by using the following primers: 5′-GGCGCGGATCCATGGAATCACTTCCACGTACTCC-3′, which contains a BamHI site, and 5′-GCGCGAGCTCGGACAGTCTCTGTCATTTGTCAAA-3′, which contains a SacI site. The KAR3 PCR product was then subcloned into BamHI-SacI-cut pGEX-KG (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to create the in-frame GAL1-GST-KAR3 translational fusion pGEX-KG/GST-KAR3 (SZB104). The KAR3 locus (−423 to 2190) was PCR amplified from a genomic template by using the following primers: 5′-CGCGCGGTCGACTTATTGTATCTTTTTCCGGCTCAT-3′, which contains a SalI site, and 5′-GCGCGGATCCCCGCATTTTCTACTAACCAATCTGGTAGAAT-3′, which contains a BamHI site, a modified stop codon, and two extra base pairs. The KAR3 PCR product was then subcloned into SalI-BamHI-cut pRS316CG to create the in-frame KAR3-GFP translational fusion pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP (SZB146). To move the Kar3-GFP fusion to a TRP1 centromeric plasmid, the SZB146 SalI-SacI fragment containing KAR3-GFP was subcloned into SalI-SacI-cut YCplac22 (Gietz and Sugino, 1988), thereby creating YCplac22/KAR3-GFP (SZB147).

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid no. | Plasmid name | Marker/plasmid type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SZB100 | pRS316CG/GPA1-GFP | URA3/CEN | This study |

| SZB146 | pRS316CG/KAR3-GFP | URA3/CEN | This study |

| SZB148 | YCplac22/KAR3-GFP | TRP1/CEN | This study |

| SZB151 | pRS316CG/CUP-GFP | URA3/CEN | Susan Lindquist (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA) |

| SZB177 | pbj1333/GFP-TUB1 | URA3/INT | John Cooper (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) |

| SZB178 | pbj1351/GFP-TUB1 | LEU2/INT | John Cooper |

| SLB126 | YCplac111/GPA1-GFP | LEU2/CEN | This study |

| SLB253 | YCplac22/GAL1-GPA1-GFP | TRP1/CEN | Stone laboratory |

| DSB132 | YCpG2/GAL1-GPA1 | URA3-LEU2/2 μ | Stone laboratory |

| MMB100 | pYEX-4T/GST-GPA1 | URA3/2μ | Metodiev et al. (2002) |

| EJ758 | pYEXdelta/Cup-Kar3-GST | URA3/CEN | Martzen et al. (1999) |

Affinity Purifications and Mass Spectrometry

The affinity-copurification, high-resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry procedures used in identifying the Gpa1-Kar3 interaction in vivo have been described previously (Metodiev et al., 2002). The native forms of Gpa1 were identified on immunoblots using an anti-Gpa1 polyclonal antibody (Stone et al., 1991). The mass spectrometric data matching to Kar3 are shown in the Supplemental Figure 1.

Nuclear Migration and Karyogamy Assays

To assay pheromone-induced nuclear migration, mid-log phase cells were treated with 18–30 nM synthetic α-factor (MPS, San Diego, CA) for 3 h and stained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as follows: 1-ml aliquots were collected, fixed with 70% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature, and DAPI was added to a final concentration of 0.1–0.2 μg/ml. After 12 min, cells were washed twice and resuspended in 20–50 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fluorescent and differential interference contrast (DIC) images were then acquired using an Axioskop 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) fitted with a 63× oil immersion objective (total magnification, 630×) and an AxioCam digital camera (Carl Zeiss), and processed with AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss). Images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Nuclear position (the coefficient of proximity) was calculated as the ratio of the shmoo tip to nucleus distance and the cell length. To assay karyogamy, 106 mid-log phase gpa1ts cells of each mating type were mixed and aspirated onto 0.45 μm MFTM-Membrane filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The filters were then incubated at 25 or 37°C on rich medium for 2, 3, and 4 h. The resulting mating mixtures were washed off the filters, sonicated briefly, and stained with DAPI. Fluorescent and DIC images were taken, superimposed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems), and scored for the percentage of binucleate zygotes.

Gpa1 localization

gpa1Δ cells transformed with the GPA1-GFP plasmid were grown to mid-log phase in glucose medium and treated with 20 nM α-factor. Wild type cells transformed with the GAL1-GPA1-GFP plasmid were grown to mid-log phase in sucrose medium, and galactose was added to 3% 1 h before treatment with 38 nM α-factor. The cultures were sampled at 0, 30, 60, and 150 min after pheromone treatment, and fluorescent images were acquired as described above. ImageJ was used to analyze the data. The outline of each cell was traced using the “segmented line” feature and the intensity of fluorescent signal around the cell periphery was quantified using the “plot profile” function. For a small number of cells, the “find edges” function was used to aid in tracing, but this function was turned off before signal quantification. The data for each cell was pasted into an Excel file (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) programmed to calculate the polarity indices. For cells that had not yet formed a mating projection, the mean intensity in the brightest fourth of the plasma membrane was divided by the mean signal intensity in the opposite quarter of the plasma membrane. For shmooing cells, the mean intensity in brightest seventh of the membrane was divided by the mean intensity in the opposite seventh of the plasma membrane. Only randomly selected unbudded cells were scored. Cells expressing the wild type Gpa1-GFP reporter were assayed in selective glucose medium.

Microtubule Dynamics and Cortical Interactions

For time-lapse movie analysis of the wild type strain expressing GFP-TUB1, cells were grown overnight in rich glucose medium to mid-log phase and treated with 30 nM α-factor (Sigma-Aldrich) 60–90 min before movie acquisition. In the Gpa1 deficiency and overexpression experiments, GAL1EG43-GPA1 (SLY168) cells expressing GFP-TUB1 were grown overnight in rich media containing 2% galactose and switched to glucose (Gpa1 turn-off) or fresh galactose (Gpa1 excess) 2 h before addition of α-factor. In the Gpa1 inactivation experiments, gpa1ts GFP-TUB1 cells were grown overnight in rich glucose medium at 25°C, treated with 30 nM α-factor for 1 h, and then shifted to 37°C and cultured for an additional hour before data acquisition. Ten-minute movies were collected at the rate of one frame per 2 s on a BX52 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a CSU-10 spinning disk confocal box (Yokogawa, Newnan, GA), a 160-mW 450- to 515-nm argon laser (National Laser, Salt Lake City, UT), and a XR Mega10 photointensified camera by Stanford Photonics (Palo Alto, CA). A 100× oil immersion objective was used (total magnification, 1500×). All time-lapse images were collected using In Vivo imaging software (QED Imaging, Pittsburgh, PA) and analyzed using ImageJ. Still images of cells expressing GFP-TUB1 and KAR3-GFP were taken and processed with the Axioskop 2 setup described above. Student's t test was used to determine statistically significant differences in microtubule dynamics and Kar3-GFP localization.

Kar3-GFP Localization and Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP) Analysis

Strains expressing KAR3-GFP were cultured as described for the time-lapse movie analysis (above), except that the gpa1ts cells were shifted to restrictive temperature concomitant with pheromone treatment. For FRAP analysis, cells were placed in a growth chamber for time-lapse multimode imaging as described previously (Maddox et al., 2000). All imaging was performed at 25°C on an Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 1.4 numerical aperture 100× DIC objective. Single focal plane images were captured by an Orca ER digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) by using a 400-ms epifluorescence exposure time (binned 2 × 2, central 600 × 600 pixel image frame, 1 pixel = 133 nm) and a 200-ms DIC exposure time. Cells were photobleached using the 488-nm line from a 100-mW argon laser (Spectra Physics, San Jose, CA) controlled by a sliding filter cube set (Conix Research, Springfield, OR). Cells were photobleached with two 35-ms laser pulses to ∼5–15% of the prebleached fluorescence intensity. During image acquisition, one prebleach data point was recorded, followed by at least 20–25 data points every 2 s. The total imaging time was at least 40 s. Recovery was not significantly altered by photobleaching for up to 30 3-s frames, in comparison with images acquired from unbleached cells (Maddox et al., 2000).

Measurements of FRAP were made on a maximum-brightness projection of z-series for each time point from time-lapse sequences at 2-s intervals. A 5 pixel × 5 pixel square (corresponding to an area of 0.66 × 0.66 mm) was placed over the bleached plus end of the microtubule, spindle pole body, or a cytoplasmic reference site (for subtracting background), and the integrated intensity was measured three independent times for each set of data. The mean intensity was determined as follows: After exporting from MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) to Excel 2000 (Microsoft), the data were corrected for background intensity and the photobleaching that takes place during image acquisition (correction derived from an average value of seven to 10 unirradiated cells observed under the experimental conditions at corresponding stages of the pheromone response or cell cycle) and then normalized to an arbitrary starting value of 1. Fluorescence recovery, or the loss of bleached fluorescence, was initially analyzed by assuming a single rate constant as described previously (Maddox et al., 2000). The dissociation rates were calculated as described previously (Maddox et al., 2000).

RESULTS

Gpa1 Interacts with Kar3

In a functional proteomics screen for proteins that interact with Gpa1, we identified the Fus3 MAPK (Metodiev et al., 2002) and the Kar3 microtubule-associated motor protein (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S1). Glutathione transferase (GST)-tagged Gpa1 was affinity purified from the lysates of vegetative and pheromone-treated cells. Proteins that copurified with Gpa1 were then visualized on two-dimensional gels, and those whose interaction with Gpa1 seemed to be stimulated by pheromone were identified by mass spectrometric analysis.

Figure 1.

Identification and characterization of the Gpa1-Kar3 interaction. (A) Identification of Kar3 as a Gpa1 interactor in pheromone-treated cells. Proteins that copurify with GST-Gpa1 were run on Immobulin two-dimensional gels. The thin white line indicates the positions of GST-Gpa1, which runs as multiple spots, and the white arrows indicate the two spots identified as Kar3 by peptide mass fingerprinting. The gel fragments encompass the region from molecular weight 60–100 kDa and pI of 7–9. Left, input. Middle, GST-Gpa1 pull-down from untreated cells. Right, GST-Gpa1 pull-down from pheromone-treated cells. (B) Reciprocal copurification of Gpa1 and Kar3 from yeast lysates. Left, pull-down of Kar3-HA with GST-Gpa1. Right, immunoprecipitation of Gpa1 with Kar3-HA. (C) Pheromone-stimulation of the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction does not depend on the induction of KAR3 transcription. Pull-down of Kar3-GST expressed from the CUP1 promoter. (D) The Gpa1–Kar3 interaction does not depend on polymerized microtubules. Left, pull-down of Kar3-HA with GST-Gpa1. Right, immunoprecipitation of Gpa1 with Kar3-HA.

The putative association of Gpa1 and Kar3 was confirmed and further characterized in a series of reciprocal pull-down assays. In lysates of cells expressing tagged forms of both proteins from their native promoters, Kar3-HA copurified with GST-Gpa1 (Figure 1B, left). Conversely, the endogenous myristylated form of Gpa1 (bottom band) was readily detected in immunoprecipitates of Kar3-HA expressed from its own promoter (Figure 1B, right). As in the proteomic screen, pheromone treatment dramatically increased the amount of Kar3-HA that was pulled down with GST-Gpa1, as well as the amount of Gpa1 that coimmunoprecipitated with Kar3-HA. Because all G proteins change their affinity for their target proteins upon activation, the apparent enhancement of the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction could be due to the shift from Gpa1-GDP to Gpa1-GTP in pheromone-treated cells. Alternatively, the relatively higher efficacy of Gpa1/Kar3 pull-down from the lysates of pheromone-treated cells could be due to a higher level of Kar3, as pheromone induces the transcription of KAR3 by 20-fold (Meluh and Rose, 1990). To test the latter possibility, we expressed KAR3-GST from the CUP1 promoter, which is not regulated by pheromone. As shown in Figure 1C, pheromone greatly enhanced the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction even though the level of Kar3 did not change. This suggests that it is the pheromone-activation of one or more signaling elements, and not the change in KAR3 expression, that augments the amount of associated Gpa1 and Kar3 in stimulated cells.

Does the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction require microtubules? Kar3 is a microtubule binding protein. Because some mammalian Gα proteins also bind microtubules, we wondered whether Gpa1 and Kar3 might copurify by virtue of a common affinity for microtubules. To test this possibility, we repeated the reciprocal pull-down assays in lysates made from cells treated first with nocodazole such that they reached full mitotic arrest, and then with pheromone. The Gpa1/Kar3 copurification yields were as robust in the nocodazole/pheromone-treated cells as in the control, despite the absence of polymerized tubulin (Figure 1D). This suggests that the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction is independent of microtubules.

Together, the results shown in Figure 1 indicate that Gpa1 and Kar3 interact in vivo, that this interaction is stimulated by pheromone, and that it is independent of both the level of Kar3 and the presence of polymerized tubulin.

Gpa1 Deficiency Mimics the Effects of kar3Δ and cik1Δ on Nuclear Migration, Cytoplasmic Microtubules, and Karyogamy

The absence of Kar3 in cells responding to pheromone confers significant defects in microtubule dynamics and nuclear migration (Maddox et al., 2003). Moreover, Kar3 is essential for nuclear congression after mating cells have fused (Meluh and Rose, 1990; Molk et al., 2006). If Gpa1 is an important regulator or mediator of Kar3 function, Gpa1 deficiency should mimic the defects conferred by kar3Δ. To test this, we used strains in which Gpa1 expression can be repressed (GAL1-GPA1), or in which Gpa1 can be inactivated (gpa1ts). It is not possible to study gpa1 null cells because GPA1 is an essential gene.

Strain SLY168 conditionally expresses GPA1 from the attenuated GAL1EG43 promoter, which is ∼1% as active as the native GAL1 promoter (Giniger and Ptashne, 1988). When this strain was grown in galactose medium, the cells accumulated approximately twofold more Gpa1 than normal; 4 h after the GAL1EG43-GPA1 cells were shifted to glucose medium, their level of Gpa1 was ∼50% of normal. We examined nuclear movement into the mating projections of pheromone-treated wild type, kar3Δ, cik1Δ, vik1Δ, and gpa1ts, as well as of wild-type cells expressing Gpa1 from the full-strength GAL1 promoter, and of GAL1EG43-GPA1 cells before and 4 h after Gpa1 expression had been turned off (Figure 2A). Both Cik1 and Vik1 are kinesin light chains that form heterodimers with Kar3, but only Cik1 is essential for the Kar3 mating functions (Page et al., 1994; Manning et al., 1999). After 2 h of pheromone treatment, the nucleus was always found near the shmoo tip in the wild-type and vik1Δ cells and in the gpa1ts cells grown at permissive temperature. By comparison, the nuclei were found farther from the shmoo tip in the kar3Δ, cik1Δ, Gpa1 turn-off cells, high-level Gpa1-overexpressing cells, and gpa1ts cells grown at restrictive temperature (p values all <10−9). Furthermore, the nucleus seemed to be connected to the shmoo tip by a single microtubule bundle in >90% of the wild-type and vik1Δ cells, whereas less than half the kar3Δ, cik1Δ, and Gpa1 turn-off cells seemed normal in this regard (Figure 2C). The K21E R22E allele of GPA1 was reported previously to confer a similar microtubule phenotype in this assay (Matheos et al., 2004). To determine whether Gpa1 plays a role in karyogamy, we scored for nuclear fusion in zygotes resulting from gpa1ts X gpa1ts matings at the permissive and restrictive temperatures. The results indicated that Gpa1 is required for normal karyogamy (Figure 2D). Together, the results of the cellular assays demonstrate that Gpa1, like Kar3 and Cik1, is required for pheromone-induced nuclear migration.

Figure 2.

Effects of Gpa1 manipulation on microtubule organization and Kar3-dependent mating processes. (A) Aberrant Gpa1 expression and function confer a kar3Δ-like defect in pheromone-induced nuclear migration. Mid-log cells were treated with pheromone for 3 h. Their nuclei were then stained with DAPI and the mean of the ratio, b/a (distance from the nucleus to the shmoo tip divided by the cell length), was determined for each strain and condition (n ≥ 56). Error bars indicate the SEM. At least 90% of the cells were shmooing in each culture; only shmooing cells were scored for nuclear position. The p values for each strain compared with wild type (15Dau) are as follows: 0.54 × 10−9 (GAL1EG43-GPA1 turned off/gpa1Δ), 0.16 × 10−10 (gpa1ts at 37°C), 0.26 × 10−13 (GAL1-GPA1 turned-on), 0.16 × 10−17 (cik1Δ), and 0.17 × 10−18 (kar3Δ). (B) Representative images used to quantify nuclear position (graphed in A). The arrowheads mark the position of the SPB. (C) Gpa1 deficiency confers a microtubule phenotype similar to those seen in kar3Δ and cik1Δ cells. Mid-log cells expressing GFP-TUB1 were treated with pheromone and fluorescence images of shmoos were acquired after 3 h. Long and mislocalized microtubules were often seen in the Gpa1-deficient cells, as is the case in kar3Δ and cik1Δ cells. The percentage of normal cells in which the nucleus seemed to be connected to the shmoo tip by a single microtubule bundle ± SEP (n = 200) were as follows: wild type, 93 ± 1.8; vik1Δ, 98 ± 1.0; Gpa1-deficient, 40 ± 3.5; kar3Δ, 34 ± 3.3; and cik1Δ, 35 ± 3.5. (D) Gpa1 deficiency confers a kar3Δ-like defect in karyogamy. Bilateral gpa1ts matings were performed for 3 and 5 h at the permissive and restrictive temperatures, respectively. The mating mixtures were then stained with DAPI and the proportion of recently fused cells with two nuclei was determined. Inactivation of Gpa1 significantly increased the proportion of binuclear cells: 3 ± 1.3% at 25°C versus 36 ± 3.7% at 37°C (p < 0.0001, n = 160; ± indicates the SEP).

Gpa1 Affects Cytoplasmic Microtubule Orientation and Dynamics

The microtubule phenotypes shown in Figure 2B and in Matheos et al. (2004) could be due to abnormalities in microtubule orientation and/or dynamics. To distinguish these possibilities, we examined time-lapse movies of cytoplasmic microtubules in pheromone-treated wild-type, gpa1ts, and GAL1EG43-GPA1 cells expressing GFP-TUB1. In all cases of aberrant Gpa1 expression and function, we observed a very significant loss of microtubule orientation (Table 3 and Supplemental Videos 1 and 2). Whereas most microtubules were oriented toward the shmoo tip in wild-type cells, the percentage of microtubules pointed away from the shmoo tip was significantly increased in the experimental strains. Deficient Gpa1 expression and inactivation of the temperature-sensitive form of Gpa1 also conferred some notable defects in microtubule dynamics. First, loss of Gpa1 increased the percentage of microtubule shrinkage events that were accompanied by a loss of cortical contact at the shmoo tip (Figure 3). The magnitude of this effect was similar to that reported for kar3Δ cells (Maddox et al., 2003). Second, the microtubules contacting any part of the cortex in Gpa1-deficient and gpa1ts cells were abnormally long, and this phenotype correlated with a decreased frequency of shrinkage events (Table 3). As shown in Figure 4 (and Supplemental Videos 1 and 2), the microtubules that contact the cortex in Gpa1-deficient cells tend to grow longer over time while spending relatively little time shrinking, compared with the dynamic instability exhibited by such microtubules in wild-type cells. Together, these data indicate that Gpa1 influences both the orientation and the dynamics of cytoplasmic microtubules in pheromone-treated cells.

Table 3.

Effect of Gpa1 deficiency, Gpa1 overexpression, and Gpa1 inactivation on microtubule orientation and dynamics

| Mean length captured Mts (μm) | Distally oriented Mts (%) | Shrinkage rate (μm s−1) | Shrinkage frequency (min−1) | Shrinkage duration (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type, 30°C | 1.33 ± 0.16 (n = 20) | 23 ± 8 (n = 135) | 0.05 ± 0.01 (n = 42) | 0.42 ± 0.02 (n = 10) | 34 ± 3 (n = 42) |

| Gal1EG43-Gpa1 (off)a | 2.27 ± 0.28* (n = 9) | 31 ± 4++ (n = 100) | 0.03 ± 0.004 (n = 6) | 0.06 ± 0.003+ (n = 10) | 32 ± 8 (n = 6) |

| Wild type, 23°C | 1.42 ± 0.13 (n = 11) | 29 ± 10 (n = 62) | 0.02 ± 0.004 (n = 10) | 0.42 ± 0.04 (n = 10) | 66 ± 8 (n = 10) |

| Wild type, 37°C | 1.45 ± 0.25 (n = 10) | 21 ± 9 (n = 63) | 0.04 ± 0.004 (n = 10) | 0.68 ± 0.04 (n = 10) | 35 ± 5 (n = 10) |

| gpa1ts, 23°C | 1.49 ± 0.20** (n = 10) | 35 ± 11** (n = 60) | 0.02 ± 0.002 (n = 9) | 0.34 ± 0.06 (n = 10) | 52 ± 6 (n = 9) |

| gpa1ts, 37°C | 2.50 ± 0.23*** (n = 10) | 66 ± 11*** (n = 53) | 0.05 ± 0.01 (n = 10) | 0.22 ± 0.07** (n = 10) | 33 ± 6 (n = 10) |

| Gal1EG43-Gpa1 (on)b | ND | 60 ± 11* (n = 80) | ND | ND | ND |

| Gal1EG43-Gpa1 (on)b, kar3Δ | ND | 21 ± 3 (n = 78) | ND | ND | ND |

Microtubule lengths, shrinkage rates, and shrinkage durations are reported as the mean ± SEM The percentages of distally oriented microtubules (Mts) and the shrinkage frequencies are reported as the mean ± SEP.

*p ≤ 0.005, **p < 0.0005, ***p < 10−6, +p < 10−8, ++p < 10−10. The statistical comparisons are as follows: gpa1ts cells at 37°C vs. wild-type cells at 37°C; gpa1ts cells at 23°C vs. gpa1ts cells at 37°C; all others vs. wild type at 30°C. ND, not determined.

a Glucose medium.

b Galactose medium.

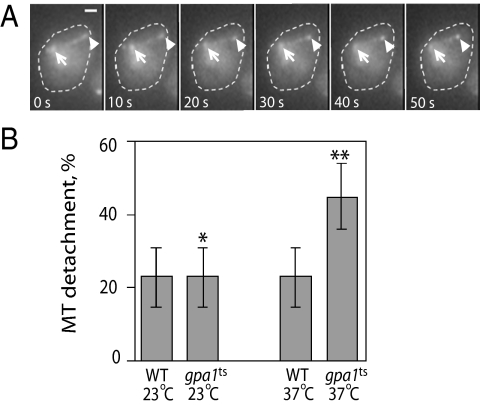

Figure 3.

Loss of microtubule–cortex contact during catastrophe. (A) Example of a shmooing cell in which the microtubule bundle loses contact with the cortex upon shrinking. The arrows mark the position of the SPB; the arrowheads mark the plus end of the microtubule. The reporter was Kar3-GFP, which decorates the entire microtubule but has greatest affinity for the plus end and the SPB (Maddox et al., 2003). Bar, 1 μm. (B) Percentage of microtubule shrinkage events resulting in loss of cortical contact. Microtubule–cortex contact was considered to be lost if the SPB did not move toward the cortex during a shrinkage event. The bar graphs indicate the mean for a given strain and condition ± the SEP. In comparison to gpa1ts at 37°C (n = 50), **p = 0.0002 for wild-type cells at 37°C (n = 59), and *p = 0.0014 for gpa1ts cells at 23°C (n = 68). For wild-type cells at 23°C, n = 90.

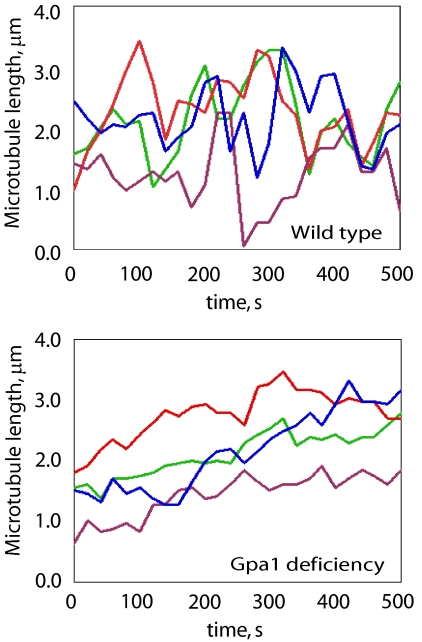

Figure 4.

Dynamics of microtubules contacting the cortex in wild type and Gpa1-deficient cells. The lengths of microtubules that maintained contact with the cortex in shmooing cells were measured every 2 s for 500 s. Each of the line graphs represents the length changes in one randomly selected microtubule per cell over this interval. The microtubules in Gpa1-deficient shmoos are typically much less dynamic than those in the control cells.

Gpa1 Affects Cytoplasmic Microtubule Orientation Independently of Its Effects on Actin

In addition to its effect on the orientation of cytoplasmic microtubules, gpa1K21E R22E confers a modest defect in pheromone-induced actin polarization (Matheos et al., 2004). Because the plus ends of cytoplasmic microtubules are moved toward the mating projection along actin cables (Hwang et al., 2003), we considered the possibility that the microtubule orientation phenotypes resulting from changes in Gpa1 expression and function were due to loss of actin polarity. Alternatively, Gpa1 could affect microtubule orientation directly or via its interaction with Kar3. To determine whether the effect of Gpa1 expression on microtubule orientation could be due to the effect of Gpa1 on actin polarization, we asked whether the two polarity defects were correlated. Cells expressing GFP-TUB1 were fixed 1–1.5 h after pheromone treatment, stained with rhodamine phalloidin, and scored for both actin and microtubule polarity (See Supplemental Figure S2 for representative images. The microtubule phenotypes conferred by changes in Gpa1 expression are also shown in Table 3). Gpa1 turn-off led to actin and microtubule polarity defects in ∼67 and 70% of the cells, respectively, and the fraction of cells exhibiting both defects was slightly less than that predicted by chance alone (42 vs. 47%). Modest overexpression of Gpa1 conferred the same types of actin and microtubule polarity phenotypes, although in a smaller proportion of cells. Again, the coincidence of the actin and microtubule polarity defects was about what was expected to occur by chance (15 vs. 12%). Whether Gpa1 expression was aberrantly high or low, a large fraction of cells exhibited an obvious defect in microtubule polarity but no defect in actin polarity (65 and 39% for Gpa1-deficient and Gpa1-overepxressing cells, respectively). Although there is an unknown degree of error in characterizing the correspondence of actin and microtubule polarity defects by this method, these data taken at face value suggest that Gpa1 orients cytoplasmic microtubules in pheromone-treated cells by a mechanism independent of its effect on actin polarity, but do not preclude the possibility that Gpa1 also affects microtubule orientation indirectly via actin.

Gpa1 Positions and Stabilizes Microtubule–Cortex Interactions at Least Partly by a Kar3-dependent Mechanism

Several observation suggest that Gpa1 and Kar3 function together during mating: the interaction of Gpa1 with Kar3 (Figure 1), the impact of Gpa1 on the Kar3-dependent processes of nuclear movement and karyogamy (Figure 2), and the involvement of both Gpa1 (Figure 3) and Kar3 (Maddox et al., 2003) in the cortical attachment of shrinking microtubules. As shown in Figure 5, Gpa1 polarizes at the plasma membrane before morphogenesis, at about the same time that cytoplasmic microtubules are first captured at the future growth site (Maddox et al., 1999). Therefore, we wondered whether Gpa1 mediates the capture and/or cortical attachment of microtubules via its interaction with Kar3. To test this hypothesis, we quantified the productive microtubule–cortex interactions in Gpa1-overexpressing, Gpa1-deficient, and control cells (Figure 6A). A productive interaction is defined as one in which microtubule contact anywhere on the cortex results in SPB movement. This requires a stable connection. In cells modestly overexpressing Gpa1, microtubule–cortex interactions were productive more often than in wild type cells (p = 0.004). Conversely, microtubule sampling of the cortex resulted in SPB movement much less often than normal in Gpa1-deficient cells (p = 0.23 × 10−4). These results suggest that Gpa1 plays a role in the attachment and/or shrinkage of microtubules at the cortex.

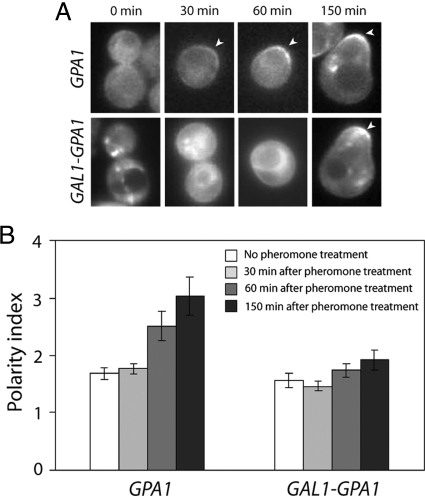

Figure 5.

Pheromone-induced polarization of Gpa1. (A) Localization of Gpa1 in pheromone-treated cells. Mid-log cells expressing Gpa1-GFP from the GPA1 promoter or overexpressing Gpa1-GFP from the GAL1 promoter were treated with pheromone and fluorescence images were acquired at the indicated time points. Cells judged to be representative of the cultures at each time point are shown. Arrowheads mark the polarized membrane localization of the reporters. (B) Quantification of Gpa1 polarization. For cells that had not yet formed a mating projection, the degree of Gpa1-reporter polarization in a given cell (polarity index) was obtained by dividing the mean signal intensity in the brightest quarter of the plasma membrane by the mean signal intensity in the opposite quarter of the plasma membrane. For shmooing cells, the polarity index was obtained by dividing the mean signal intensity in the brightest seventh of the plasma membrane by the mean signal intensity in the opposite seventh of the plasma membrane. Bar graphs represent the mean of the polarity indices cells at each time point (n = 15); error bars indicate SEM. The wild type Gpa1-GFP reporter became significantly polarized before mating projection formation (for untreated vs. pheromone-treated Gpa1-GFP cells, p = 0.0077 at 60 min and p = 0.0006 at 150 min). In contrast, cells modestly overexpressing the Gpa1-GFP reporter from the GAL1 promoter showed no significant polarization (comparing 0 min to 30, 60, and 150 min, the p values were 0.51, 0.33, and 0.10 for the Gal1-Gpa1-GFP cells, respectively).

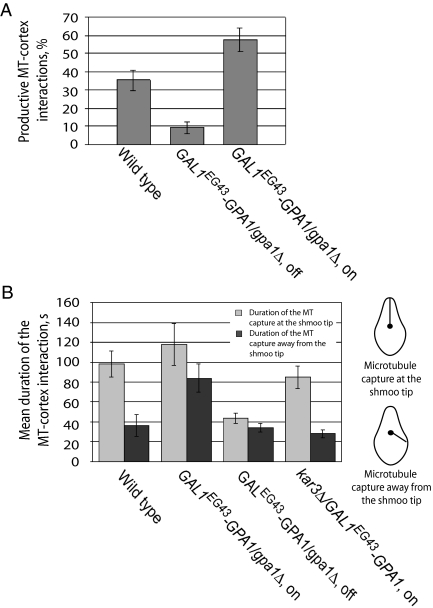

Figure 6.

Effect of Gpa1 on microtubule–cortex interactions. (A) Gpa1 expression level positively correlates with the proportion of productive microtubule–cortex interactions. Pheromone-treated cells of the indicated genotypes and conditions were scored for the percentage of cortical contacts that resulted in movement of the SPB toward the shmoo tip by using GFP-TUB1 as a reporter. The bar graphs indicate the mean for a given strain and condition ± the SEP. In comparison with the wild-type cells (n = 71), p = 0.004 for the Gpa1-overexpressing cells (n = 59) and p = 0.00002 for the Gpa1-deficient cells (n = 87). (B) Gpa1 influences the location and duration of microtubule–cortex interactions. Pheromone-treated cells of the indicated genotypes/conditions were analyzed to determine where their cytoplasmic microtubules were captured, and for how long. The bar graphs indicate the mean duration of contact for a given strain and condition ± SEM. Light bars indicate capture at the shmoo tip; dark bars indicate capture away from the shmoo tip. The significant differences are as follows: p = 0.002 for capture at (n = 20) versus away (n = 10) from the shmoo tip in wild-type cells; p = 0.008 for capture away from the shmoo tip in wild-type cells versus Gpa1-overexpressing cells (n = 12); p = 0.0002 for capture away from the shmoo tip in Gpa1-overexpressing versus Gpa1-overexpressing kar3Δ cells (n = 14); p = 0.0002 for capture at the shmoo tip in wild-type versus Gpa1-deficient cells (n = 20). The relevant insignificant differences are as follows: p = 0.21 for capture at the tip in wild-type versus Gpa1-overexpressing cells (n = 18); p = 0.06 for capture at (n = 20) versus away (n = 13) from the shmoo tip in Gpa1-deficient cells; p = 0.09 for capture at the tip in wild-type versus Gpa1-overexpressing kar3Δ cells (n = 18); p = 0.43 for capture away from the tip in wild type versus Gpa1-deficient cells (n = 13); p = 0.23 for capture away from the tip in wild-type versus Gpa1-overexpressing kar3Δ cells.

To differentiate between defects in capture and shrinkage, we quantified the effects of aberrant Gpa1 levels on the localization and duration of microtubule–cortex interactions (Figure 6B). In the control cells, microtubule-cortex interactions lasted ∼3 times longer at the shmoo tip than away from it (p = 0.002), as expected from previous reports (Shaw et al., 1997; Maddox et al., 1999). In contrast, microtubule–cortex interactions were significantly shorter at the shmoo tips of Gpa1-deficient cells (p = 0.0002) and did not last significantly longer than elsewhere around these cells (p = 0.06). This suggests that the enhanced stability at the shmoo tip depends on Gpa1. Consistent with this, overexpression of Gpa1 increased the duration of microtubule–cortex interactions away from the shmoo tip (p = 0.008), without significantly affecting this measure at the shmoo tip (p = 0.21). The more uniform distribution of stable microtubule–cortex contacts around these cells correlates with the loss of Gpa1 polarity that results from Gpa1 overexpression (Figure 5). Notably, the effect of excess Gpa1 on microtubule–cortex interaction was completely suppressed by deletion of KAR3 (Figure 6B). Just as in the control cells, microtubule-cortex interactions lasted ∼3 times longer at the shmoo tip than away from it in cells overexpressing Gpa1 but lacking Kar3. The observation that kar3Δ is epistatic to Gpa1 overexpression in this assay is consistent with the idea that Kar3 is downstream of Gpa1 in the pathway connecting pheromone stimulation to microtubule-cortex interactions as suggested by the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction, although the data do not exclude the involvement of other factors or direct Gpa1–microtubule contact. Note that in the absence of Kar3, the bias of microtubule–cortex contact to the shmoo tip might be maintained by the interaction of microtubule plus ends with Kar9 or other factors. In contrast, Gpa1 deficiency confers a significant loss of microtubule-cortex contact at the shmoo tip. This suggests that Gpa1 interacts directly with microtubule plus ends or with other microtubule-associated proteins in addition to Kar3. Together, the data shown in Figure 6 indicate that Gpa1 is required for the maintenance of microtubule–cortex contact and that this function at least partially depends on Kar3 but do not allow us to determine whether Gpa1 also affects microtubule shrinkage.

Gpa1 Affects the Dynamic Association of Kar3 with Microtubule Plus Ends at the Shmoo Tip

Kar3 localizes to the plus ends of cytoplasmic microtubules and couples them to the cortex of the shmoo tip when they are shrinking (Maddox et al., 2003). Because Gpa1 interacts with Kar3 and is also highly concentrated at the shmoo tip, we wondered whether the cortical localization of Kar3 depends on Gpa1. To test this, we first asked whether Gpa1 inactivation or deficiency would affect the shmoo tip localization of a Kar3-GFP reporter. As shown in Figure 7, Kar3-GFP was slow to accumulate at the shmoo tip in cells either lacking (gpa1ts cells at 37°C) or deficient (GAL1EG43-GPA1 cells in glucose) in Gpa1 function, and the peak percentage of experimental cells that showed a clear shmoo-tip signal was about half that observed in the relevant control cultures (p < 0.05 for both experiments). As a second test of the idea that Gpa1 regulates Kar3 localization, we evaluated the effect of aberrant Gpa1 expression and function on the turnover rates of the Kar3-GFP reporter at shmoo tips by using FRAP analysis (Reits and Neefjes, 2001). After the wild-type and experimental strains were treated with pheromone and allowed to form mating projections, the Kar3-GFP signal at the plus ends of shmoo-tip microtubules was photobleached, and the recovery of fluorescence was quantified and plotted against the time after photobleaching. As shown in Table 4, overexpression of Gpa1 from the full-strength GAL1 promoter greatly increased the half-time for recovery. Conversely, Gpa1 deficiency and inactivation of Gpa1 by shifting gpa1ts cells to the restrictive temperature greatly decreased this measure. As a negative control, we photobleached the Kar3-GFP signal at the SPB of pheromone-treated cells. Here, the half-time for recovery was unaffected by manipulation of Gpa1. Together, the Kar3-GFP localization and FRAP data indicate that Gpa1 positively affects the association of Kar3 with microtubule plus ends in the mating projection, consistent with the idea that Gpa1 recruits Kar3-bound microtubules to the cortex at the shmoo tip.

Figure 7.

Accumulation of Kar3-GFP at the tips of shmooing cells is partially dependent on Gpa1. (A) Effect of Gpa1 inactivation on Kar3-GFP shmoo tip localization. gpa1ts cells expressing Kar3-GFP were grown to mid-log phase at 23°C and either maintained at the permissive temperature or shifted to 37°C concomitant with pheromone treatment (0 time). Aliquots were taken and fluorescence images were acquired at the indicated time points. Data points represent the mean percentage of shmooing cells with clear fluorescence at their tips ± the SEP. Tips were examined in all focal planes. In comparison with gpa1ts cells maintained at 23°C (closed circles), those shifted to 37°C (open circles) showed significantly weaker tip localization at each time point: p = 0.024 at 1 h (n = 70), p = 0.003 at 2 h (n = 111), p = 0.0005 at 3 h (n = 129), and p = 0.0008 at 4 h (n = 184). (B) Effect of Gpa1 deficiency on Kar3-GFP shmoo tip localization. Fluorescent images of pheromone-treated wild-type and Gpa1-deficient cells were acquired at the indicated time points and scored as described above. Data points represent the mean percentage of shmooing cells with clear fluorescence at their tips ± the SEP. In comparison with wild-type cells (closed squares), the Gpa1-deficient cells (open squares) showed significantly weaker Kar3-GFP tip localization until the control culture began to recover: p = 0.0022 at 1 h (n = 10), p = 0.00013 at 1.5 h (n = 30), p = 0.016 at 2 h (n = 181), p = 0.030 at 2.5 h (n = 222), p = 0.036 at 3 h (n = 250), and p = 0.056 at 3.5 h (n = 200). (C) Representative images used to quantify the effect of Gpa1 deficiency on Kar3-GFP localization (graphed in A).

Table 4.

FRAP analysis of Kar3-GFP at microtubule plus ends near the shmoo tip

| k (rate of dissociation), a.u | t1/2, s | R, % recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type, glucose | 0.104 ± 0.026 | 6.99 ± 1.61 | 58 ± 18 |

| Wild type, galactose | 0.115 ± 0.037 | 6.66 ± 3.03 | 62 ± 17 |

| GAL1-GPA1 (on)a | 0.050 ± 0.015+ | 14.86 ± 3.76++ | 63 ± 14 |

| GAL1-GPA1 (off)b | 0.094 ± 0.027 | 8.03 ± 2.24 | 60 ± 20 |

| GAL1EG43-GPA1/gpa1Δ (off)b | 0.156 ± 0.047* | 4.76 ± 1.17* | 63 ± 16 |

| GAL1EG43-GPA1/gpa1Δ (on)a | 0.097 ± 0.024 | 7.29 ± 1.52 | 56 ± 19 |

| gpa1ts, 37°C | 0.222 ± 0.078** | 3.35 ± 2.64+ | 49 ± 23 |

| gpa1ts, 25°C | 0.113 ± 0.067 | 6.79 ± 2.47 | 62 ± 16 |

All values are reported as the mean ± SD, n = 10 for each measurement.

*p ≤ 0.01, **p ≤ 10−3, +p ≤ 10−4, ++p < 10−5; The statistical comparisons are as follows: Cells overexpressing Gpa1 (lines 3 and 5) and cells deficient in Gpa1 (lines 4 and 6) vs. wild-type cells cultured in the corresponding medium (glucose or galactose), and gpa1ts cells at 23°C vs. gpa1ts cells at 37°C (lines 7 and 8).

a Galactose medium.

b Glucose medium.

DISCUSSION

The yeast mating reaction is a directional response. A mating yeast cell orients toward the strongest source of pheromone and grows in that direction. At the same time, the nucleus moves toward the tip of the mating projection. As the pheromone-induced polarization of growth and nuclear position depend on dynamic changes in F-actin and microtubule cables, these phenomena provide an opportunity to study regulation of the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons by an external signal.

In cells, cytoplasmic microtubules grow and shrink at their plus ends (Maddox et al., 1999), and Kar3 is required to maintain their cortical attachment as they shrink (Maddox et al., 2003). Recently, it has been shown that Cik1 targets Kar3 to microtubule plus ends and that the Kar3/Cik1 heterodimer triggers plus-end depolymerization in vitro (Sproul et al., 2005). On the basis of these results, it has been proposed that Kar3/Cik1 stimulates the plus-end depolymerization of cytoplasmic microtubules in mating cells while maintaining their cortical attachment, thus drawing the nucleus toward the shmoo tip (Maddox et al., 2003; Maddox, 2005; Molk and Bloom, 2006). This model raises two key questions: 1) What anchors Kar3 to the cortex? And 2) What, if anything, regulates Kar3-mediated depolymerization of the microtubules coupled to the cortex?

In an alternate but not mutually exclusive model of nuclear migration (Molk and Bloom, 2006), microtubules periodically lose contact with the shmoo tip and shrink back to the SPB. These are replaced by newly nucleated microtubules that are transported into the mating projection along actin cables. The nucleus is thus moved toward the shmoo tip as shorter and shorter microtubules bind to the cortex. Because Kar3 localizes to free as well as cortical microtubule plus ends (Maddox et al., 2003), cortical capture of Kar3-bound microtubules could contribute to this mechanism. It is also possible that individual microtubules in the attached bundle briefly lose contact with the cortex as they shorten and have to be recaptured (Maddox et al., 1999). Both of these scenarios require an element that captures Kar3-bound microtubule plus ends at the shmoo tip. Until now, there have been no candidates for this role.

In this investigation, we have shown that pheromone stimulates an interaction between Gpa1and Kar3 that does not depend on microtubules or increased transcription of either GPA1 or KAR3 (Figure 1), that Gpa1 positively affects the association of Kar3 with the plus ends of microtubules at the shmoo tip (Figure 7 and Table 4), and that Gpa1 stimulates productive microtubule–cortex interactions (Figure 6A). We have also shown that Gpa1 affects the position and duration of microtubule-cortex contact (Figure 6B) and that this effect depends on Kar3. Finally, we found that Gpa1 turn-off and temperature-sensitive inactivation caused detachment of the microtubules from the cortex during shrinkage events (Figure 3), as is seen in kar3Δ cells (Maddox et al., 2003). From these observations, we infer that Gpa1 is a cortical anchor for Kar3. As such, Gpa1 fills two postulated functions: It recruits Kar3-bound microtubule plus ends to the shmoo tip, and it helps to maintain microtubule–cortex contact during shrinkage events. In proposing that Gpa1 serves these functions, however, we do not imply that Gpa1 is the only Kar3 anchor. In fact, the partial Kar3-GFP mislocalization phenotype that results when Gpa1 is compromised suggests that there is at least one more such element. It is also possible that other proteins which interact with Gpa1 at the plasma membrane contribute to the observed regulation of microtubules in pheromone-treated cells. These include the Gpa1 GAP protein Sst2, the pheromone-specific Gβγ dimer, and the Fus3 MAP kinase. Although our results do not argue against the involvement of these elements, our data strongly suggest that Gpa1, a protein that polarizes on the membrane early in the pheromone response, helps to position and anchor microtubules at the growth site of mating cells by interacting with Kar3, a known microtubule binding protein.

Given that microtubule plus ends are localized to the mating projection along actin cables (Hwang et al., 2003), could the effect of Gpa1 perturbation on microtubules be entirely due to the impact of Gpa1on actin polarity? Our results argue strongly against this possibility. First, actin is not known to influence the stability and duration of microtubule-cortex contact, as do Kar3 and Gpa1 (Figures 3 and 6). Second, Gpa1 manipulation conferred obvious microtubule abnormalities in a large fraction of cells that displayed apparently normal actin polarity (Supplemental Figure S2). Third, there was no detectable pheromone-induced nuclear migration whatsoever in Gpa1-deficient cells, as in kar3Δ and cik1Δ cells (Figure 2). The severity of this phenotype is not consistent with the mild actin polarity defect conferred by Gpa1 deficiency. The simplest explanation of these data is that Gpa1 regulates microtubule orientation (i.e., localization to the mating projection) indirectly via actin, whereas Gpa1 affects microtubule-cortex contact and positioning via Kar3. Of course, the Gpa1–Kar3 interaction might also affect microtubule orientation.

Although the effects of Gpa1 on microtubule–cortex contact are readily explained as the direct consequences of Gpa1 binding to Kar3 and Kar3 binding to the plus ends of microtubules, Gpa1 may be more than merely a passive anchor for Kar3. The Gα protein seems to affect microtubule dynamics as well. Gpa1 deficiency and inactivation confer an increase in the mean length of microtubules contacting the cortex that correlates with a reduction in the number of shrinkage events (Table 3). It has been proposed that catastrophe is induced when microtubules contact the cortex of vegetative cells (Carminati and Stearns, 1997), and Sproul et al. (2005) have raised the possibility that plus-end depolymerization is stimulated at the cortex of the shmoo tip (Sproul et al., 2005). Given the infrequency of cortical microtubule shrinkage in Gpa1 turn-off and gpa1ts cells, the regulator of microtubule catastrophe at the shmoo tip could be Gpa1. Through its interaction with Kar3, Gpa1 might bias the dynamic instability of microtubules attached at the shmoo tip so that shrinkage predominates over growth. It is also possible, of course, that Gpa1 affects microtubules directly. Mammalian Gα proteins have been reported to interact directly with tubulin (Wang et al., 1990; Chen et al., 2003). Our data do not distinguish between these possibilities.

In summary, the results presented here suggest that Gpa1 serves as an externally regulated positional determinant and anchor for Kar3, a previously unappreciated role for Gα proteins. We propose that by concentrating at the incipient mating projection, Gpa1 recruits Kar3-bound microtubule plus ends to the shmoo tip and stabilizes their interaction with the cortex during shrinkage. Our data also suggest that Gpa1 positively regulates the frequency of microtubule shrinkage events at the cortex. By regulating both the localization of Kar3 and the initiation of microtubule shrinkage, Gpa1 may simultaneously ensure that the nuclear tether is appropriately positioned and that it shortens upon contacting the cortex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kerry Bloom and Jeff Molk for assisting in the FRAP analysis, Kerry Bloom and Vladimir Gelfand for helpful discussions, Dmitry Suchkov for automating the calculation of polarity indices, and Mark Longtine for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB-0453964 to D.E.S. and National Institutes of Health grant GM-47337 (to J. C.).

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0069) on April 22, 2009.

REFERENCES

- Acuto O., Cantrell D. T cell activation and the cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:165–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affolter M., Weijer C. J. Signaling to cytoskeletal dynamics during chemotaxis. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ayscough K. R., Drubin D. G. A role for the yeast actin cytoskeleton in pheromone receptor clustering and signalling. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:927–930. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell L. A walk-through of the yeast mating pheromone response pathway. Peptides. 2005;26:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell E., Halatek I. M., Kim H. J., Ellicott A. T., Obukhov A. A., Stone D. E. Effect of the pheromone-responsive Gα and phosphatase proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the subcellular localization of the Fus3 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:1135–1150. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1135-1150.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butty A. C., Pryciak P. M., Huang L. S., Herskowitz I., Peter M. The role of Far1p in linking the heterotrimeric G protein to polarity establishment proteins during yeast mating. Science. 1998;282:1511–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati J. L., Stearns T. Microtubules orient the mitotic spindle in yeast through dynein-dependent interactions with the cell cortex. J. Cell Biol. 1997;138:629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N. F., Yu J. Z., Skiba N. P., Hamm H. E., Rasenick M. M. A specific domain of Giα required for the transactivation of Giα by tubulin is implicated in the organization of cellular microtubules. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15285–15290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.-Y., Kranz J. E., Mahanty S. K., Park K.-S., Elion E. A. Characterization of Fus3 localization: active Fus3 localizes in complexes of varying size and specific activity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:1553–1568. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz R. D., Sugino A. New yeast—Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniger E., Ptashne M. Cooperative DNA binding of the yeast transcriptional activator GAL4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:382–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulimari P., Knieling H., Engel U., Grosse R. LARG and mDia1 link Gα12/13 to cell polarity and microtubule dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:30–40. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang E., Kusch J., Barral Y., Huffaker T. C. Spindle orientation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends on the transport of microtubule ends along polarized actin cables. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:483–488. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. L., Hartwell L. H. Courtship in S. cerevisiae: both cell types choose mating partners by responding to the strongest pheromone signal. Cell. 1990;63:1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90507-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-J., Lindquist S. Oligopeptide-repeat expansions modulate “protein only” inheritance in yeast. Nature. 1999;400:573–576. doi: 10.1038/23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden K., Snyder M. Cell polarity and morphogenesis in budding yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1998;52:687–744. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox P., Chin E., Mallavarapu A., Yeh E., Salmon E. D., Bloom K. Microtubule dynamics from mating through the first zygotic division in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:977–987. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox P. S. Microtubules: Kar3 eats up the track. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:R622–R624. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox P. S., Bloom K. S., Salmon E. D. The polarity and dynamics of microtubule assembly in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:36–41. doi: 10.1038/71357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox P. S., Stemple J. K., Satterwhite L., Salmon E. D., Bloom K. The minus end-directed motor Kar3 is required for coupling dynamic microtubule plus ends to the cortical shmoo tip in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1423–1428. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning B. D., Barrett J. G., Wallace J. A., Granok H., Snyder M. Differential regulation of the Kar3p kinesin-related protein by two associated proteins, Cik1p and Vik1p. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:1219–1233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martzen M. R., McCraith S. M., Spinelli S. L., Torres F. M., Fields S., Grayhack E. J., Phizicky E. M. A biochemical genomics approach for identifying genes by the activity of their products. Science. 1999;286:1153–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheos D., Metodiev M., Muller E., Stone D., Rose M. D. Pheromone-induced polarization is dependent on the Fus3p MAPK acting through the formin Bni1p. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:99–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meluh P. B., Rose M. D. KAR3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell. 1990;60:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90351-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metodiev M. V., Matheos D., Rose M. D., Stone D. E. Regulation of MAPK function by direct interaction with the mating-specific Gα in yeast. Science. 2002;296:1483–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.1070540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molk J. N., Bloom K. Microtubule dynamics in the budding yeast mating pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:3485–3490. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molk J. N., Salmon E. D., Bloom K. Nuclear congression is driven by cytoplasmic microtubule plus end interactions in S. cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:27–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch A. Microtubule organization and function in epithelial cells. Traffic. 2004;5:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2003.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nern A., Arkowitz R. A. A Cdc24p-Far1p-Gβγ protein complex required for yeast orientation during mating. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:1187–1202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page B. D., Satterwhite L. L., Rose M. D., Snyder M. Localization of the Kar3 kinesin heavy chain-related protein requires the Cik1 interacting protein. J. Cell Biol. 1994;124:507–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne D., Legesse-Miller A., Gao L., Dong Y., Bretscher A. Mechanisms of polarized growth and organelle segregation in yeast. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:559–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.103108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S. I., Hadwiger J. A., Lorincz A. T. Protein kinase activity associated with the product of the yeast cell division cycle gene CDC28. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:4055–4059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reits E. A., Neefjes J. J. From fixed to FRAP: measuring protein mobility and activity in living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E145–147. doi: 10.1038/35078615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M. D. Nuclear fusion in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996;12:663–695. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw S. L., Yeh E., Maddox P., Salmon E. D., Bloom K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. J. Cell Biol. 1997;139:985–994. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F., Fink G. R., Hicks J. B., editors. Laboratory Course Manual for Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sproul L. R., Anderson D. J., Mackey A. T., Saunders W. S., Gilbert S. P. Cik1 targets the minus-end kinesin depolymerase kar3 to microtubule plus ends. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1420–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. E., Cole G. M., Lopes M., Goebl M., Reed S. I. N-myristoylation is required for function of the pheromone-responsive Gα protein of yeast: conditional activation of the pheromone response by a temperature-sensitive N-myristoyl transferase. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1969–1981. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanDrogen F., Stucke V. M., Jorritsma G., Peter M. MAP kinase dynamics in response to pheromones in budding yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:1051–1059. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:259–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19960315)12:3%3C259::AID-YEA901%3E3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Yan K., Rasenick M. M. Tubulin binds specifically to the signal-transducing proteins, Gsα and Giα 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1239–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler E. A., et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.