Abstract

Men’s use of two coercive sexual tactics was tracked over 10 years in a sample of at-risk young men (N=201). Patterns were identified for each tactic. For the tactic using drugs or alcohol to go further sexually, non-coercers (63%) and coercers (37%) were identified. For the tactic of going further sexually after the woman said “no,” three patterns were identified—noncoercers (10%), low-level coercers who used the tactic 5 times or less over 10 years (42%), and high level coercers who used the tactic more than 5 times over 10 years (43%). The associations between coercive tactics and two dating behaviors—physical aggression toward a partner and risky sexual behaviors—were examined using multilevel linear modeling. For both coercive tactics, main effects and interaction effects with time occurred for physical aggression toward a partner. The most coercive men perpetrated the most physical aggression toward a partner between ages 18–22 years, but sexual coercion was unrelated to partner abuse between ages 22–27 years. Results suggest men vary in their use of coercive sexual tactics over time and the frequency of coercion varies based on tactic. Preliminary evidence suggests the use of coercive sexual tactics is associated with physical aggression toward a partner but not risky sexual behaviors, though the strength of the association varies over time.

Keywords: sexual coercion, dating behaviors, high, risk sex, aggression

INTRODUCTION

Sexual coercion in dating relationships is a pervasive and serious problem among adolescents and college students (Alksnis, Desmarais, Senn, & Hunter, 2000; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987; O’Sullivan, 2005). Sexually coercive acts involve verbal and psychological persuasion, manipulation, and use of substances to obtain sexual contact or sexual favors from an unwilling or ambivalent partner (Ageton, 1983). According to official statistics from the National Center for Victims of Crime (2005), teens are the most sexually victimized of all age groups. In a sample of high school females, 54% reported experiencing sexual coercion on a date (Poitras & Lavoie, 1995) and up to 63% of collegiate women report experiencing sexual coercion (for review, see Craig, 1990). Women who have experienced sexual victimization may later experience considerable consequences impacting psychological and physical health, as well as quality of life (Koss, Heise, & Russo, 1994). Teens and young adults are not only victims but also perpetrators of sexual coercion; for example, in one study, 50% of collegiate men reported sexual coercion (Craig, 1990; Koss et al., 1987).

Although it is clear that sexual coercion is a problem for both adolescents and adults, it is less clear exactly how coercion is expressed in dating contexts, how frequently coercive tactics are used, and how men’s use of coercive tactics changes over time. Most official statistics and studies capture serious forms of coercion, such as using physical force to obtain sex, thus omitting men who use less aggressive tactics to obtain sex. Men who perpetrated serious forms of sexual aggression, such as rape, also report other problematic dating behaviors such as risky sex and physical aggression (Malamuth, 2003; Malamuth, Linz, Heavey, Barnes, & Acker, 1995; Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991); however, the co-occurrence of sexual coercion and other problematic dating behaviors has not been as extensively explored. Understanding the dating behaviors of men who use sexual coercion may provide additional avenues for prevention and intervention programs for violence against women. To clarify how mild forms of coercion are expressed in dating relationships, how the use of these tactics varies over time, and what problematic dating behaviors co-occur with sexual coercion, the current study examined the developmental course, correlates, and frequency of sexual coercion, by tracking men’s use of two coercive sexual tactics over 10 years; namely, offering a woman drugs or alcohol in the hopes of gaining sex and going further sexually after the woman said “no.”

Developmental Course of Sexual Coercion

Recent studies have examined the consistency of sexual aggression over time. In the first longitudinal study of sexual aggression, Malamuth and colleagues (1995) found the confluence model predicted sexual aggression against women at a 10-year follow up. The confluence model is an etiological conceptualization of sexual aggression in which hostile masculinity (violence, misogynistic beliefs) and impersonal sex (sex outside of a dating relationship) interact as predictors of sexual and nonsexual violence toward women. The authors found young men who endorsed model components at Time 1 reported sexual aggression at Time 2. The study provided important information about factors influencing initiation or re-offense, but did not identify different patterns of offending, for example, aggressors who desisted offending between assessments. The current study will apply components from the confluence model to men’s use of sexually coercive tactics, in that the association between coercive tactics and partner physical aggression and sex with risky partners will be examined over time.

Abbey and McAuslan (2004) clarified differential developmental patterns of offending by assessing collegiate men at two times, at approximately age 21 years and again 1 year later. Self-reports of perpetration were used to identify four patterns of sexually coercive behavior: nonassaulters (never assaulted), past assaulters (reported an assault in Time 1 but not Time 2), new assaulters (reported an assault in Time 2 but not Time 1), and repeat assaulters (reported an assault in both Time 1 and Time 2). Repeat assaulters tended to have the highest levels of substance use, delinquency, misogynistic beliefs, acceptance of the use of verbal pressure, and prior sexual experiences. This study was the first to identify groups of sexual perpetrators in a longitudinal design. However, the study assessed only college students and spanned only 1 year. In a further 1-year longitudinal study, Hall, DeGarmo, Eap, Teten, and Sue (2006) identified four groups of perpetrators (nonaggressors, initiators, desisters, and persisters) using similar criteria to Abbey and McAuslan (2004). Again, consistent with the confluence model, the groups showed predicted associations with levels of misogynistic beliefs and delinquency, with the persistent group generally exhibiting the highest levels of deviancy. Continuity in sexual coercion has been found across a 5-year period in a study in which both delinquency and perpetration of sexual coercion in adolescence were found to influence sexual coercion in adulthood. White and Hall Smith (2004) assessed collegiate men for 5 consecutive years (~ages 19–24 years) and found that sexual coercion in adolescence increased the likelihood of perpetration in college. To build on past work on sexual coercion over time, the current study not only will test components from the confluence model but also will examine developmental patterns behavior in order to understand how men’s use of tactics varies over time.

Problematic Dating Behaviors

Previous models of sexual coercion, such as the confluence model, include problematic dating behaviors, other than coerced sex, such as physical aggression toward a partner and unsafe sexual practices. Like sexual coercion, physical aggression toward a partner can have deleterious effects on the victims’ physical and mental health (Holzworth-Munroe, Smutzler, & Sandin, 1997) and is a serious and prevalent problem in relationships. Physical aggression toward a partner includes hitting, biting, slapping, shooting, and stabbing one’s romantic partner. Among high school females, 23% reported experiencing physical aggression from a date (Feiring, Deblinger, Hoch-Espada, & Haworth, 2002). Studies of women over age 18 years have found that 20–50% of women reported physical aggression from a partner. Approximately 15% of high school men reported perpetrating physical aggression against a dating partner (Feiring et al., 2002), and 18–44% of collegiate men reported physical violence toward their partner (Ryan, 1998; Sigelman, Berry, & Wiles, 1984). These studies suggest that physical aggression by a partner is a threat to women during their adolescence and into adulthood.

In addition to aggressive dating behaviors, boys and girls are initiating intercourse at younger ages, with 62% of high school seniors estimated to be sexually active in 2003 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). Younger men tend to report having more sexual partners than their older counterparts (Johnson, Wadsworth, Wellings, Bradshaw, & Field, 1992) and, therefore, are at higher risk for contracting sexually transmitted infections. Unfortunately, less than 20% of couples whose behaviors put them at risk for HIV reported using condoms consistently (Catania, Coates, & Kegeles, 1994). Early initiation of sex, a high number of sexual partners, and sexual risk taking has been associated with antisocial and externalizing behaviors, in general, (Capaldi, Crosby, & Stoolmiller, 1996; Capaldi, Stoolmiller, Clark, & Owen, 2002; French & Dishion, 2003; Valois, Oeltmann, Waller, & Hussey, 1999) and sexual aggression, in particular (Lalumiere, Harris, Quinsey, & Rice, 2005; Malamuth, 2003; Malamuth et al., 1995; Malamuth et al., 1991). The current study will extend past findings by examining the association between problematic dating behaviors and two specific, mild forms of sexual coercion.

Current Study

To understand specifically how sexual coercion was expressed in relationships, how the use of coercive tactics varied over time, and what problematic dating behaviors co-occurred with sexually coercive tactics, the current study had two primary aims: to identify patterns of coercion based on frequency of using coercive tactics and to understand how other dysfunctional dating behaviors—physical aggression toward a partner and risky sexual behaviors—co-occurred with the use of coercive sexual tactics over 10 years.

METHOD

Participants

The current study was conducted using the OYS data set, which contains 19 yearly assessments for men from ages 9–10 to ages 27–29 years. Two cohorts (N = 104 and N = 102, respectively) of participants were recruited from neighborhoods with higher than average rates of delinquency in 1984–1985. Elementary schools with a high incidence of delinquency in the area for the medium-sized metropolitan area were identified, and boys from the fourth grade were invited to participate in the study. Risk was therefore identified by context rather than by problematic behaviors of the boys. A total of 206 (74.4%) of the 277 eligible families consented to participate (Capaldi & Patterson, 1987). In 1984–1985, 52% of the OYS parents were of lower socioeconomic status or unemployed, and one third was receiving governmental assistance in the form of welfare or food stamps. By ages 25–26 years, 62.2% of the sample had been arrested at least once, and one quarter had been unemployed or had not attended school for at least a month in their lifetime. The sample reflected the ethnic distribution of the area of Eugene and Springfield, Oregon, in that 90% was European American, 3.4% Hispanic, 3.4% African American, 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 1% Asian/Pacific Islander. The small proportion of ethnic minority participants precluded analysis of ethnic and cultural differences.

Procedure

Ninety-five percent of the sample has been retained over the course of 19 years of data collection, although only 10 years of existing data were used in the current study. Extensive tracking procedures were used, and the participants were reimbursed for each aspect of the assessment (Capaldi, Chamberlain, Fetrow, & Wilson, 1997). Researchers assessed the participants in a variety of settings, including their home and school. A combination of self-report measures and interviews were used to obtain the data included in the current study.

Measures

This study examined the frequency of specific, low base-rate behaviors. Between one and three items were selected to measure the behaviors of interest. Two sexually coercive tactics were tracked over time, offering a woman drugs or alcohol in the hopes of gaining sex and going further sexually after the woman said “no.” In addition to coercive sexual tactics, physical aggression toward a partner and risky sexual behaviors were assessed.

Sexual Coercion

For the purpose of the current study, coercion was defined as any tactic employed with the expressed intention to facilitate sex or sexual contact. This liberal definition was used to “cast a wide net” for the incidence and prevalence of coercion over time. Although victim and perpetrator perception of an episode and the outcome of the coercive episode (sex vs. no sex) are important considerations, they were outside the scope of the current study. Therefore, men reported on the frequency of their use of two forms of sexual coercion over the past year, using three items from the Sex Survey 1 (Capaldi, Metzler, Ary, & Noell, 1991). The first form of sexual coercion involved the use of substances to facilitate sex. The tactic was measured with the items: How often did you offer a girl alcohol in hopes of going further? How often did you offer a girl drugs in hopes of going further? The two items were measured on a five-point Likert scale where 1 = never and 5 = always. The correlation between these items each year across the 10 years of assessment ranged from r = .26 to r = .71. The second form of sexual coercion involved ignoring a woman’s response to sexual advances. Men responded to the item: How often did you go further after she said no? The item was measured on a five-point Likert scale in which 1 = always and 5 = never. Prior to performing the analyses, all items were recoded so that 0 = never and 4 = always.

Partner-Directed Physical Aggression

In order to measure violence against a romantic partner, the following two items were selected from the Adjustment with Partner Scale (Kessler, 1990): When you have a disagreement, how often do you push, throw things, slap, spank your partner? When you have a disagreement how often do you kick, bite, hit, choke, burn, beat your partner? These items were measured on a four-point Likert scale on which 1 = often and 4 = never. Prior to performing the analyses, items were recoded so that 1 = never and 4 = always. The correlation between these items across the 10 years of assessment ranged from r = .33 to r = .62.

High-Risk Heterosexual Behaviors

The high-risk sexual behavior of sex with unknown or risky partners was measured using three items from the Sex Survey 2 (Capaldi et al., 1991), all asked for the past year: How many girls have you had sex with who were also having sexual intercourse with other people? How many times have you had sexual intercourse with a girl you know has ever injected herself with drugs? How many times have you had intercourse with a girl you didn’t know well? These items were measured on a 9-point scale on which 0 = 0, 1 = 1, 2 = 2, 3 = 3, 4 = 4, 5 = 5–10, 6 = 11–20, 7 = 21–40, 8 = 41+. Cronbach’s alpha for these items over the 10 years ranged from .44 to .74.

Data Analysis

In addition to descriptive analyses, analyses took place in two phases. First, the patterns of sexual coercion were developed for each sexually coercive tactic. Groups were formed based on the overall frequency of the use of tactics. A median split was used to determine groupings. Men were excluded from pattern development if they had missing values for four or more data points on the sexual coercion variables. In all, 5 of the 206 men had missing data on the coercion items and were excluded from all analyses. In general, there was not a substantial amount of missing data, so listwise deletion was used to manage missing data for the physical aggression toward a partner and high-risk sexual behavior constructs. To understand the association between the use of coercive tactics and other problematic dating behaviors, multilevel linear modeling (MLM) was used. MLM examines both between and within group continuous variables that are repeatedly measured over time. All analyses were performed in SPSS 14.0.

RESULTS

Before examining the study hypotheses, descriptive statistics for the variables were generated and are shown in Table 1. Correlations were performed to examine the strength of the associations among the 10-year means of the variables. Going further after the woman said “no” was significantly associated with using substances to go further sexually, r = .47, p < .05, and with physical aggression toward a partner, r = .30, p <. 05. Using substances to go further sexually was significantly associated with physical aggression toward a partner, r = .25, p < .05, and with risky sexual behaviors, r = .24, p < .05. Partner physical aggression was significantly associated with risky sexual behaviors, r = .24, p < .05.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Coercive Tactics over 10 years

| Using Substances to Go Further Sexuallya | Going Further After “No”a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M | SD | n | M | SD | n |

| 18 | 0.08 | (0.29) | 199 | 0.23 | (0.58) | 199 |

| 19 | 0.09 | (0.37) | 199 | 0.23 | (0.56) | 199 |

| 20 | 0.14 | (0.39) | 198 | 0.18 | (0.48) | 198 |

| 21 | 0.09 | (0.27) | 200 | 0.81 | (0.92) | 200 |

| 22 | 0.08 | (0.26) | 197 | 0.83 | (0.92) | 197 |

| 23 | 0.03 | (0.14) | 197 | 0.83 | (1.04) | 198 |

| 24 | 0.07 | (0.22) | 200 | 0.76 | (0.84) | 200 |

| 25 | 0.04 | (0.20) | 198 | 0.73 | (0.98) | 198 |

| 26 | 0.05 | (0.23) | 194 | 0.73 | (0.83) | 194 |

| 28 | 0.03 | (0.15) | 188 | 0.67 | (0.89) | 188 |

Item values range from 0 to 4.

Development of Coercive Sexual Patterns

Patterns of coercion were based on overall frequency of use of each tactic. A median split determined how groups were defined. The median frequency for using substances to go further sexually was zero, so the group was divided into noncoercers (f = 0) and coercers (f > 0). Going further after she said “no” had a median of 5.0, so three groups were formed: non-coercers (f = 0), low-level coercers (0 > f ≥ 5), and high-level coercers (f > 5). When examining the tactic of using substances to go further sexually, 127 (63%) were noncoercers and 74 (37%) of the men were coercers. In terms of going further after she said “no,” 20 (10%) were noncoercers, 85 (42%) were low-level coercers, and 96 (48%) were high-level coercers. ANOVAs confirmed that groups were significantly different from each other in terms of the overall frequency of coercion (using substances, F(1, 199) = 121.64, p < .001; going further, F(2, 198) = 139.66, p < .001). Chi-square tests indicted significantly different frequencies of participants were classified in each pattern for using substances to go further sexually, χ2(1) = 13.98, p < .001, and going further after “no,” χ2(2) = 50.36, p < .001.

Co-occurrence of Dysfunctional Relationship Behaviors

Multilevel linear modeling was selected as an analytic technique to account for the repeated measurement of multiple behaviors over 10 years. One model was evaluated for each coercive tactic with the coercive tactic as the dependent variable (Level 1) and the co-occurring dating behaviors and time as the independent variables (Level 2). Coercive patterns were created only for the purpose of describing the incidence and prevalence of using coercive tactics over time; so, to test study hypotheses, the frequencies of use of coercive tactics at each age (continuous variables) were used as the dependent variables. Physical aggression toward a partner, risky sexual behaviors, and their interactions with time were included as fixed effects. Time was included as a repeated effect.

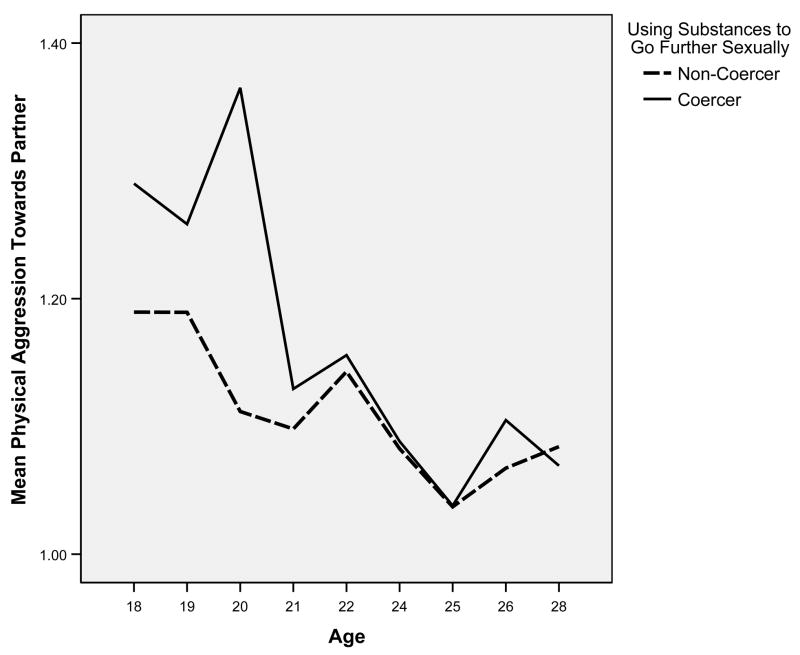

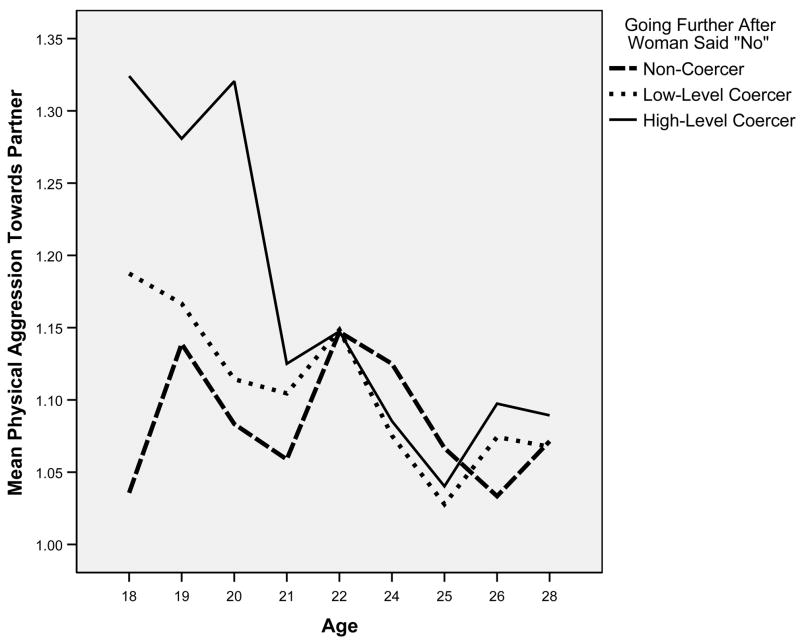

For both tactics, significant main effects were found for physical aggression toward a partner (using substances to go further sexually, F(1, 413.58) = 10.77, p = .001; going further after “no,” F(1, 309.96) = 11.01, p = .001, and significant interaction effects were found between physical aggression toward a partner and time (using substances to go further sexually, F(1, 274.40) = 9.06, p = .003; going further after “no,” F(1, 219.67) = 31.42, p < .001). Risky sexual behaviors were not significantly associated with either tactic. Using the coercive pattern for illustrative clarity, the main effect and interaction effects are depicted in Figures 1 and 2. Overall, the frequency of partner physical aggression decreased over time, though the rate of change between ages 18–22 years varied as a function of frequency of coercive tactic use.

Figure 1.

Physical aggression toward a partner by pattern of coercive tactic Using Substances to go Further Sexually over 10 years.

Figure 2.

Physical aggression toward a partner by pattern of coercive tactic Going Further after Woman Said “No” over 10 years.

DISCUSSION

The current study had two aims: (1) to create patterns of coercive sexual behavior, and (2) to examine the co-occurrence of two problematic dating behaviors, which were extrapolated from the Confluence Model, with mild sexually coercive tactics over time. We extended previous longitudinal studies of sexual perpetration by examining coercive patterns in an at-risk sample, over 10 years. Men differed in the frequency with which they used each tactic, as 90% of the sample reported going further after the woman said “no” versus 37% who reported offering alcohol or drugs in hopes of going further sexually.

Findings suggest using sexually coercive tactics is associated with physical aggression toward a partner until age 22 years. For both tactics, the most frequently coercive men participated in the most relationship violence until their early 20s. On the other hand, using coercive tactics was not significantly associated with sex with risky partners during the 10 years. Findings provide preliminary evidence that sexual coercion and physical aggression toward a partner are more likely to co-occur than sexual coercion and high risk sex, though the association may be age limited. The association between sexual coercion and physical aggression extends past studies that examined more serious forms of aggression (Hines & Saudino, 2003; Ryan, 1998; Sigelman et al., 1984) and suggests men who use mild sexual coercion may be at risk for relationship violence. Therefore, results suggest only certain predictors for sexual aggression from the confluence model may be applicable to more mild forms of coercion. In other words, in the current study, conflict with women and sexual coercion were associated as in Malamuth et al. (1995), but the co-occurrence of impersonal sex and sexual coercion was not, indicating the association may only occur for men who report severe forms of sexual aggression, such as rape.

Although the overall incidence of going further after “no” increased over time and the incidence of using substances to go further sexually decreased over time, the association between both of these tactics and physical aggression toward a partner was found only until age 22 years, suggesting it is not the coercion that is developmentally limited, but instead the association between coercion and aggression. Overall, rates of physical aggression went down across the 11-year period. Rates of physical aggression toward a partner have been found to be highest at young ages and to decrease with time (Gelles & Straus, 1988). Using National Youth Study data, Morse (1995) found that more than one half of the couples (55%) reported any physical aggression toward a partner in the past year at age 18 to 24 years, but this prevalence declined over the ensuing 10 years to 32%, with a decrease in prevalence with age for men (37% to 20%) and women (48% to 28%). Findings of the current study indicate that the high rates of physical aggression at the younger ages may be due to the co-occurrence of sexual coercion and aggression for some men, and that changes over time in their physical aggression in particular have a major role in the decrease of physical aggression toward partner with age. Future studies are needed to understand what factors exacerbate or ameliorate use of coercive tactics and other problematic dating behaviors over time. The current results suggest prevention and intervention programs for relationship violence should also target the use of sexual coercion, at least through the early 20s.

Most surprising of all findings was the prevalence of sexual coercion reported in an at-risk sample. Most single time-point, cross-sectional studies estimate that 30–50% of men are sexually coercive (Craig, 1990; Koss et al., 1987), whereas in 10 years, over 90% of the sample reported using one or both sexually coercive tactics at least once. These findings indicate, as might be expected, that repeated measurements of sexual coercion across time detect a higher prevalence of using any coercive tactic than a cross-sectional study. That said, the incidence of sexual coercion was quite low, as evidenced by medians of 0 and 5 for using substances to go further sexually and going further after “no,” respectively. For the high-level coercers who went further after “no,” the mean frequency over 10 years was less than 10, indicating the most persistent coercers used the tactics approximately once per year. The current study suggests a majority of at-risk men use sexually coercive tactics at least once during adolescence and early adulthood, a finding that has not been reported to date.

Some aspects of the sample, measurement, and design limited the findings. The greatest study limitation involved the use of single, self-report items as proxies for sexual coercion. The items did not account for perpetrator or victim perception of the event, and it is unclear whether or not the tactics actually resulted in a sexual encounter. In reality, some of the exchanges included in the study may have been perceived as consensual. A large literature has demonstrated that perception of coercion is influenced by many factors such as tactic used and gender of the perpetrator (Oswald & Russell, 2006), though these elements were not included in the current study. The exchanges captured in the current study may also have included “token resistance” or sexual miscommunication (e.g., Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004) rather than coercion, but it is impossible to know if any of the episodes were consensual without partners’ reports of the interactions. Therefore, further study of these issues is indicated.

Another limitation involved the lack of diversity of participants. The participants were predominantly heterosexual, which precluded the analysis of same-sex coercion and dating violence. Men in the study were drawn from the same community in the Pacific Northwest and were ethnically homogenous. Cultural factors, such as African American ethnicity, have been shown to protect against the high-risk sexual behavior—problem-behavior association (Black, Ricardo, & Stanton, 1997). Therefore, the associations obtained in the current study may not apply to other cultural groups.

Sexual coercion and high-risk sexual behaviors were measured for the first time at age 18 years, precluding detection of early-onset adolescent coercers. The measurement of sexually coercive behaviors in late adolescence also makes it difficult to establish age of onset for coercion because much sexual coercion begins in high school (Poitras & Lavoie, 1995) and would not have been captured by late adolescent assessments. Thus, causal relationships among the constructs cannot be implied with confidence.

The current study examined patterns of sexual coercion across 10 years for a community sample of at-risk men. It is the first, long-term, longitudinal study to identify subgroups based on sexually coercive tactics and to examine other co-occurring dysfunctional dating behaviors. Results indicate that most at-risk Euro-American men in the current study sample used a coercive sexual tactic at least once and that the men who used coercive tactics most frequently also reported the most physical aggression toward a partner. Findings provide preliminary evidence that prevention programs for at-risk young men should target multiple problematic dating behaviors, including sexual coercion and physical aggression.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Physical Aggression Toward a Partnera by Coercive Sexual Pattern over 10 years

| Using Substances to Go Further Sexually | Going Further after “No” | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive Pattern | Noncoercer | Coercer | Noncoercer | Low Level Coercer | High Level Coercer | Total | n | ||||||

| Age | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 18 | 1.19 | (0.45) | 1.29 | (0.59) | 1.04 | (0.13) | 1.19 | (0.41) | 1.32 | (0.63) | 1.23 | (0.51) | 116 |

| 19 | 1.19 | (0.50) | 1.26 | (0.45) | 1.13 | (0.29) | 1.17 | (0.45) | 1.28 | (0.54) | 1.21 | (0.48) | 163 |

| 20 | 1.11 | (0.33) | 1.37 | (0.65) | 1.08 | (0.26) | 1.11 | (0.28) | 1.32 | (0.63) | 1.21 | (0.49) | 166 |

| 21 | 1.10 | (0.32) | 1.13 | (0.26) | 1.06 | (0.17) | 1.10 | (0.36) | 1.13 | (0.26) | 1.11 | (0.30) | 160 |

| 22 | 1.14 | (0.37) | 1.16 | (0.37) | 1.15 | (0.29) | 1.15 | (0.36) | 1.15 | (0.39) | 1.15 | (0.37) | 159 |

| 24 | 1.08 | (0.24) | 1.09 | (0.21) | 1.13 | (0.39) | 1.08 | (0.20) | 1.09 | (0.22) | 1.08 | (0.23) | 171 |

| 25 | 1.04 | (0.13) | 1.04 | (0.13) | 1.07 | (0.18) | 1.03 | (0.12) | 1.04 | (0.14 | 1.04 | (0.13) | 174 |

| 26 | 1.07 | (0.26) | 1.10 | (0.24) | 1.03 | (0.13) | 1.07 | (0.29) | 1.10 | (0.23) | 1.08 | (0.25) | 166 |

| 28 | 1.08 | (0.28) | 1.07 | (0.20) | 1.07 | (0.27) | 1.07 | (0.21) | 1.09 | (0.28) | 1.08 | (0.25) | 172 |

Note. No data for ages 23 or 27 years.

Item values range from 1 to 4.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations for Risky Sexual Behaviorsa by Coercive Sexual Pattern over 10 years*

| Using Substances to Go Further Sexually | Going Further after “No” | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive Pattern | Noncoercer | Coercer | Noncoercer | Low Level Coercer | High Level Coercer | Total | n | ||||||

| Age | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 18 | 0.51 | (0.93) | 1.10 | (1.72) | 0.55 | (1.09) | 0.68 | (1.33) | 0.88 | (1.40) | 0.76 | (1.34) | 143 |

| 19 | 0.79 | (1.42) | 1.02 | (1.49) | 0.88 | (1.50) | 0.82 | (1.38) | 0.94 | (1.50) | 0.88 | (1.45) | 166 |

| 20 | 0.61 | (1.36) | 1.28 | (1.70) | 0.20 | (0.31) | 0.82 | (1.45) | 1.06 | (1.71) | 0.87 | (1.53) | 173 |

| 21 | 0.42 | (0.96) | 0.76 | (1.22) | 0.39 | (0.76) | 0.49 | (1.08) | 0.65 | (1.14) | 0.56 | (1.08) | 180 |

| 22 | 0.55 | (1.25) | 0.99 | (1.40) | 0.50 | (0.92) | 0.67 | (1.36) | 0.80 | (1.38) | 0.72 | (1.33) | 184 |

| 23 | 0.22 | (0.65) | 0.41 | (0.81) | 0.08 | (0.32) | 0.27 | (0.76) | 0.36 | (0.75) | 0.30 | (0.72) | 172 |

| 24 | 0.36 | (0.78) | 0.68 | (1.27) | 0.13 | (0.36) | 0.54 | (1.14) | 0.51 | (0.97) | 0.49 | (1.02) | 175 |

| 25 | 0.24 | (0.76) | 0.33 | (0.72) | 0.23 | (0.53) | 0.30 | (0.95) | 0.27 | (0.59) | 0.28 | (0.75) | 176 |

| 26 | 0.48 | (1.23) | 0.71 | (1.31) | 1.06 | (1.74) | 0.69 | (1.49) | 0.36 | (0.84) | 0.57 | (1.26) | 171 |

| 28 | 0.33 | (0.95) | 0.52 | (1.01) | 0.07 | (0.14) | 0.48 | (0.96) | 0.39 | (1.06) | 0.40 | (0.98) | 172 |

Note. No data for age 27 years.

Item values range from 0 to 8.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by Grant HD 46364 from the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) and Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders Branch, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), U.S. PHS. Andra L. Teten is supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, VA Special MIRECC Fellowship Program in Advanced Psychiatry and Psychology, Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perpetration of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageton SS. The dynamics of female delinquency, 1976–1980. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1983;21:555–584. [Google Scholar]

- Alksnis C, Desmarais S, Senn C, Hunter N. Methodological concerns regarding estimates of physical violence in sexual coercion: Overstatement or understatement? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29:323–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1001962219365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Ricardo IB, Stanton B. Social and psychological factors associated with AIDS risk behaviors among low-income, urban, African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1997;7:173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Chamberlain P, Fetrow RA, Wilson JE. Conducting ecologically valid prevention research: Recruiting and retaining a “whole village” in multimethod, multiagent studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:471–492. doi: 10.1023/a:1024607605690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Stoolmiller M. Predicting the timing of first sexual intercourse for adolescent males. Child Development. 1996;67:344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Metzler C, Ary D, Noell J. Sex Survey 1–6. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center; 1991. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. An approach to the problem of recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and STD contraction. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Coates TJ, Kegeles S. A test of the AIDS risk reduction model: Psychosocial correlates of condom use in the AMEN cohort survey. Health Psychology. 1994;13:548–555. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance system. 2005 Retrieved March 27, 2005, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/SS/SS5302.pdf.

- Craig ME. Coercive sexuality in dating relationships: A situational model. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:395–423. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Deblinger E, Hoch-Espada A, Haworth T. Romantic relationship aggression and attitudes in high school students: The role of gender, grade, and attachment and emotional styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:373–385. [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Dishion TJ. Predictors of early initiation of sexual intercourse among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Intimate violence: The causes and consequences of abuse in the American family. Simon and Schuster; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, DeGarmo DS, Eap S, Teten AL, Sue S. Initiation, desistance, and persistence of men’s sexual aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:732–742. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Saudino KJ. Gender differences in psychological, physical, and sexual aggression among college students using the revised Conflict Tactics Scale. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:197–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:179–213. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Bradshaw S, Field J. Sexual lifestyles and HIV risk. Nature. 1992;360:410–412. doi: 10.1038/360410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The national comorbidity survey. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Heise L, Russo NF. The global health burden of rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1994;18:509–537. [Google Scholar]

- Lalumiere ML, Harris GT, Quinsey VL, Rice ME. The causes of rape: Understanding individual differences in the male propensity for sexual aggression. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM. Criminal and noncriminal sexual aggressors: Integrating psychopathy in a hierarchical-mediational confluence model. In: Prentky RA, Janus ES, Seto MC, editors. Sexually coercive behavior: Understanding and management. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 2003. pp. 33–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men’s conflict with women: A 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:353–369. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, Tanaka JS. Characteristics of aggressors against women: Testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse BJ. Beyond the Conflict Tactics Scales: Assessing gender differences in partner violence. Violence Victims. 1995;10:251–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Statistics: Teen victimization. 2005 Retrieved March 27, 2005, from http://www.ncvc.org/ncvc/

- O’Sullivan LF. Sexual coercion in dating relationships: Conceptual and methodological issues. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2005;20:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald DL, Russell BL. Perceptions of sexual coercion in heterosexual dating relationships: The role of aggressor gender and tactics. The Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:87–95. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, Muehlenhard CL. Was it rape? The function of women’s rape myth acceptance and definitions of sex in labeling their own experiences. Sex Roles. 2004;51:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras M, Lavoie D. A study of the prevalence of sexual coercion in adolescent heterosexual dating relationships in a Quebec sample. Violence and Victims. 1995;10:299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KM. The relationship between courtship violence and sexual aggression in college students. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13:377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK, Berry CJ, Wiles KA. Violence in college students’ dating relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14:530–548. [Google Scholar]

- Valois RF, Oeltmann JE, Waller J, Hussey JR. Relationship between number of sexual intercourse partners and selected health risk behaviors among public high school adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Hall Smith P. Sexual assault perpetration and reperpetration: From adolescence to young adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2004;31:182–202. [Google Scholar]