Abstract

A case of fulminant dissecting cellulitis of the scalp in a fifteen-year-old African American male is reported. The presentation was refractory to standard medical treatment such that treatment required radical subgaleal excision of the entire hair-bearing scalp. Reconstruction was in the form of split-thickness skin grafting at the level of the pericranium following several days of vacuum-assisted closure dressing to promote an acceptable wound bed for skin grafting and to ensure appropriate clearance of infection. Numerous nonsurgical modalities have been described for the treatment of dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, with surgical intervention reserved for patients refractory to medical treatment. The present paper reports a fulminant form of the disease in an atypical age of presentation, adolescence. The pathophysiology, etiology, natural history, complications and treatment options for dissecting cellulitis of the scalp are reviewed, and the authors suggest this method of treatment to be efficacious for severe presentations refractory to medical therapy.

Keywords: DCS, Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, Perifolliculitis capitis

Abstract

Un cas de cellulite disséquante fulminante du cuir chevelu chez un Afro-Américain de 15 ans est déclaré. La présentation était réfractaire au traitement médical classique. Il a donc fallu procéder à l’excision sousgaléale radicale de tout le cuir chevelu. La reconstruction a pris la forme d’une greffe dermo-épidermique du péricrâne après la pose d’un pansement de cicatrisation par pression négative pendant plusieurs jours afin de favoriser la formation d’une plaie permettant la greffe et une clairance pertinente de l’infection. De nombreuses modalités chirurgicales ont déjà été décrites dans le traitement de la cellulite disséquante du cuir chevelu, l’intervention chirurgicale étant réservée aux patients réfractaires au traitement médical. Le présent rapport présente une forme fulminante de la maladie à un âge atypique, l’adolescence. Les auteurs examinent la physiopathologie, l’étiologie, l’évolution naturelle, les complications et les possibilités de traitement de la cellulite disséquante du cuir chevelu et proposent cette méthode de traitement comme efficace en présence de graves présentations réfractaires à la médicothérapie.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (DCS), or perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens, is often part of the previously described follicular occlusion triad of DCS, hidradenitis suppurativa and acne conglobata (1). First reported by Spitzer (2) in 1903, followed by Wise and Parkhurst (3) in 1921, it was not named DCS until 1931 by Barney (4). Subsequently, a common etiology of follicular occlusion has been well documented in the medical literature. As the pilosebaceous apparatus becomes occluded by keratinous material, follicular expansion and inflammation occur, with or without further complication of bacterial superinfection.

The natural history of DCS is that of a chronic, relapsing and remitting disease process, occurring often in postadolescent African-American males (5). The disease is usually found in the vertex of the scalp and posterior neck crease, and begins with localized abscesses that progress to diffuse inflammatory phlegmatic involvement of the subcutaneous tissues. Chronic draining sinus formation is typical, resulting in cicatricial scarring with scalp alopecia. The most dreaded complications of DCS are calvarial osteomyelitis and malignant degeneration to squamous cell carcinoma (6).

The differential diagnosis includes infectious etiologies, most commonly bacterial, fungal and acid-fast organisms. A diagnosis of DCS, confirmed by histopathology, is characterized by epidermal fibrinoid necrosis, underlying severe acute and chronic inflammation with abscesses, and foreign body giant cell reaction (7). Many nonsurgical treatment modalities have been reported with varying degrees of success, including oral and intralesional antibiotics, isotretinoin, corticosteroids, ionizing radiation and, more recently, pulsed neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser treatment (8). Surgical treatments have included local incision and drainage, and excision with skin grafting or flap reconstruction (8,9). All treatments result in some form of scarring or alopecia because the surgical goal is obliteration of the scalp’s obstructed pilosebaceous apparatus and associated glands.

CASE PRESENTATION

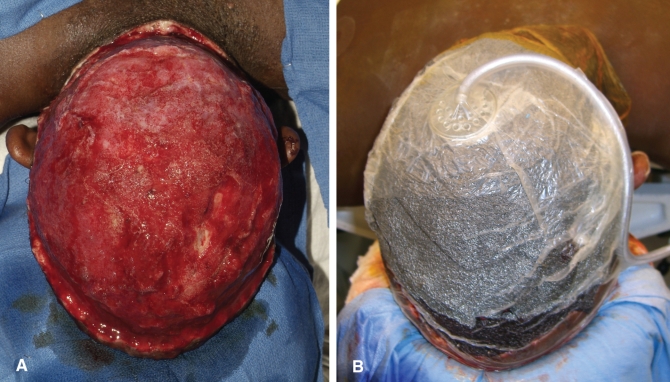

A 15-year-old African American male presented to the emergency room at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, USA, with a painful left leg. A clinical diagnosis of a left leg abscess was established, and on review of his symptoms, he was also noted to have a severe infection of the scalp (Figures 1A to 1C). His scalp symptoms had been present for approximately six months, and during this interval he had been treated by multiple dermatologists for tinea capitis. Treatments had included antimicrobial shampoos, acetic acid wound dressings, topical tretinoin, topical corticosteroids, intralesional ciprofloxacin, oral cephalexin and oral griseofulvin, with limited efficacy.

Figure 1).

Preoperative presentation of fulminant dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (A, B and C)

He was brought to the operating room by the pediatric surgery service for incision and drainage of the left leg abscess, and plastic surgery was consulted intraoperatively regarding the infected scalp. A presumptive clinical diagnosis of DCS was made, and confirmatory biopsies and tissue cultures of the scalp were obtained. Tissue cultures subsequently grew multiple strains of Pseudomonas species. Histopathology revealed epidermal fibrinoid necrosis, underlying severe acute and chronic inflammation with abscesses and foreign body giant cell reaction, confirming a diagnosis of DCS. Antipseudomonal antibiotics were initiated and a calvarial computed tomography scan was obtained, to rule out underlying osteomyelitis. Subsequently, given the severity of the disease presentation, informed consent was obtained for wide local excision of the entire hair-bearing scalp. The postsurgical sequelae of permanent alopecia was discussed with the patient and family and they were accepting of this outcome.

Wide subgaleal plane dissection was performed because the subcutaneous tissue plane was involved in the disease process; care was taken to preserve the pericranium (Figure 2A). Due to the extent of the infection, antibiotics and low-suction (50 mmHg intermittent suction) vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy (Kinetic Concepts Inc, USA) were applied to promote a vascular bed and to clear the infection (Figure 2B). Pericranial hypertrophy and granulation tissue formation was evident after 10 days of VAC therapy. Next, split-thickness skin grafts were harvested from the lateral thigh and meshed in a 1:1.5 ratio, inset and secured by a xeroform-wrapped, mineral oil-soaked, cotton tie-over bolster dressing (Figures 3A and 3B). One week postapplication, the initial dressing change revealed grafts with near 100% take, without any recipient site complications. Nine months postoperatively there was no recurrence of scalp disease and the skin grafts showed excellent maturation and remodelling (Figures 4A to 4C). The patient reported exuberant enthusiasm with results and an overall dramatic improvement in quality of life.

Figure 2).

Wide local excision of diseased scalp (A); Vacuum-assisted closure dressing application (B)

Figure 3).

Meshed split-thickness skin grafting to scalp (A) with xeroform-wrapped, mineral oil-soaked, cotton tie-over bolster dressing (B)

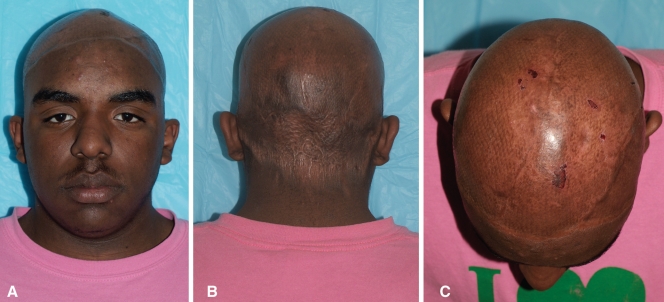

Figure 4).

Nine-month postoperative follow-up of patient with well-healed scalp grafts, recurrence-free, and with associated alopecia (A, B and C)

DISCUSSION

DCS, first described by Spitzer in 1903 (2), is a chronic inflammatory disease with a clinical presentation of scalp inflammation, infection, sinus formation, nodules, scarring and alopecia, resulting in substantial limitations in quality of life. Although the etiology of DCS is unknown, it is certainly related to follicular obstruction, and DCS is a component of the follicular occlusion triad associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and acne conglobata (10,11). Similar to the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris, follicular obstruction involves keratinous plugging of the pilosebaceous apparatus, followed by dilation and secondary bacterial infection. Perifolliculitis follows, and repeated episodes of inflammation and infection result in sinus tracts, scarring and alopecia. The natural history of DCS is a course of relapsing and remitting episodes of inflammatory and infectious nodules, draining sinuses and abscesses.

The differential diagnosis for DCS includes folliculitis decalvans, discoid lupus erythematosus and dermatitis papillaris capillitii (12). The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds with histopathological confirmation. Histopathology reveals follicular and perifollicular inflammation consisting primarily of neutrophils, with associated foreign body giant cells and lymphocytes. Abscesses, generally due to staphylococcal species, associated scarring and alopecia are prevalent. Additionally, the chronic inflammatory wound produced by DCS can result in malignant degeneration to squamous cell carcinoma (6).

Many patients with this disease have limited regions of the scalp affected, which respond well to conventional medical therapies. For more severe cases, localized regions of affected scalp require wide local excision and primary closure or coverage with split-thickness skin grafting. Most instances result in some form of alopecia at resolution or control of the disease.

In the large majority of DCS patients, the above treatment is an acceptable temporizing measure, and rarely does this disease produce such fulminant clinical findings requiring total scalp excision, as found with our patient. It has been suggested that the long-term efficacy of local treatments is poor, with frequent relapses and disease progression (5). Our patient had more than six months of unremitting disease, associated with a significant loss of quality of life. The complete involvement of the scalp by the disease made localized or less aggressive treatments a less desirable option.

We propose that in these patients, wide local excision of the entire hair-bearing scalp and pilosebaceous units be performed with a period of intermittent local therapy to allow for resolution of any underlying superinfection, followed by reconstruction with split-thickness skin grafts or free tissue transfer. For chronic wounds, it is imperative to rule out calvarial osteomyelitis with a computed tomography scan, as well as to perform a biopsy to exclude underlying malignancy. We chose to use the VAC as our intermittent therapy because it was an easy-to-apply, compact unit design, allowed for good control of exudate, eliminated painful dressing changes, and promoted granulation tissue and pericranial hypertrophy. Low-suction settings were chosen to prevent excessive bleeding through the perforating emissary veins.

Our patient accepted and even welcomed the associated alopecia resulting from the intervention as preferable to his preoperative quality of life. However, a female patient may not welcome such a result. Additionally, we found our patient to have an atypical age of presentation at 15 years. Our search of the literature found this to be the only case of an adolescent with a diagnosis of DCS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chicarilli ZN. Follicular occlusion triad: Hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18:230–7. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spitzer L. Dermatitis follicularis et parifollicularis conglobata. Dermatol Ztschr. 1903;10:109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise F, Parhurst HJ. A rare form of suppurating and cicatrizing disease of the scalp. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1921;4:750. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barney RE. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1931;23:503. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyer DG, Williams RM. Perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens: Report of six cases. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:378–84. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1962.01590030076010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry SS, Gaither DH, King LE., Jr Squamous cell carcinoma arising in dissecting perifolliculitis of the scalp. A case report and review of secondary squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:673–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams CN, Cohen M, Ronan SG, Lewandowski CA. Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:378–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krasner BD, Hamzavi FH, Murakawa GJ, Hamzavi IH. Dissecting cellulitis treated with the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1039–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellew SG, Nemerofsky R, Schwartz RA, Granick MS. Successful treatment of recalcitrant dissecting cellulitis of the scalp with complete scalp excision and split-thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1068–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montes LF, Curtis AC. The follicular occlusion triad. Postgrad Med. 1968;43:108–12. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1968.11693144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Self SJ, Montes LF. Follicular occlusion triad. South Med J. 1970;63:156–60. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halder RM. Hair and scalp disorders in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:378–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]