Abstract

Congenic DRF.f/f rats are protected from type 1 diabetes (T1D) by 34 Mb of F344 DNA introgressed proximal to the gimap5 lymphopenia gene. To dissect the genetic factor(s) that confer protection from T1D in the DRF.f/f rat line, DRF.f/f rats were crossed to inbred BBDR or DR.lyp/lyp rats to generate congenic sublines that were genotyped and monitored for T1D, and positional candidate genes were sequenced. All (100%) DR.lyp/lyp rats developed T1D by 83 days of age. Reduction of the DRF.f/f F344 DNA fragment by 26 Mb (42.52–68.51 Mb) retained complete T1D protection. Further dissection revealed that a 2 Mb interval of F344 DNA (67.41–70.17 Mb) (region 1) resulted in 47% protection and significantly delayed onset (P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp). Retaining <1 Mb of F344 DNA at the distal end (76.49–76.83 Mb) (region 2) resulted in 28% protection and also delayed onset (P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp). Comparative analysis of diabetes frequency in the DRF.f/f congenic sublines further refined the RNO4 region 1 interval to ∼670 kb and region 2 to the 340 kb proximal to gimap5. All congenic DRF.f/f sublines were prone to low-grade pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration around ducts and vessels, but <20% of islets in nondiabetic rats showed islet infiltration. Coding sequence analysis revealed TCR Vβ 8E, 12, and 13 as candidate genes in region 1 and znf467 and atp6v0e2 as candidate genes in region 2. Our results show that spontaneous T1D is controlled by at least two genetic loci 7 Mb apart on rat chromosome 4.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, BB rat, T cell receptor, autoimmune

characteristics of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in both human and the BioBreeding spontaneously diabetes-prone (BBDP) rat include polyuria, hyperglycemia, ketoacidosis, insulitis, and insulin dependency for life. As in human T1D, islets are infiltrated by mononuclear cells at the time of onset with rapid hyperglycemia due to a complete loss of islet β-cells (32). The genetic etiology of human T1D remains complex and although the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (HLA DQ) on chromosome 6 accounts for ∼40% of T1D risk, the number of non-HLA genetic factors is increasing steadily (2, 7).

The BB rat offers a powerful model to dissect both genetic contributions and mechanisms by which immune-mediated beta cell killing induces T1D (3, 4, 15, 17–21, 27, 28, 46). As in humans, the major genetic determinant of susceptibility in the BB rat is the MHC (Iddm1) on rat chromosome (RNO) 20. The class II MHC locus RT1B/D.u/u (RT1.u/u), an ortholog of human HLA DQ (9), is necessary but not sufficient for T1D in the BBDP rat and other RT1.u/u-related rat strains with spontaneous (24, 47) or induced T1D (8, 43). In BBDP, a null mutation in the gimap5 gene (lyp; Iddm2) on RNO4 (14, 27) causes lymphopenia and is tightly linked to spontaneous T1D development. The DR.lyp/lyp rat with 2 Mb of BBDP DNA encompassing gimap5 introgressed into the genome of related BBDR rats (BioBreeding resistant to spontaneous T1D) are also 100% lymphopenic and 100% spontaneously diabetic (11). With complete T1D penetrance and tight regulation of onset, the congenic DR.lyp/lyp rat line offers distinct advantages in identification of genes responsible for disease progression.

It is possible to induce T1D in BBDR rats (32) and related RT1u/u rats (8) by administration of polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly I:C, an activator of innate immunity), the Treg depleting cytotoxic DS4.23 anti-ART2.1 (formerly RT6) monoclonal antibody or by viral infection (34). This indicates that the BBDR has an underlying genetic susceptibility to T1D. In crosses between WF and either BBDP or BBDR rats, a quantitative trait locus (QTL) important for induced T1D (Iddm14, previously designated Iddm4) was mapped to RNO4 (6, 29).

Interestingly, F344 DNA introgressed between D4Rat253 and D4Rhw6 into the congenic DR.lyp/lyp genetic background resulted in a lymphopenic but nondiabetic rat (designated DRF.f/f) (11). Protection from T1D in the DRF.f/f congenic rat line led us to conclude that spontaneous T1D in the BB rat is controlled, in part, by a diabetogenic factor(s) independent of the gimap5 mutation (76.84 Mb) on RNO4. This congenic interval is encompassed within Iddm14, raising the possibility that the Iddm14 locus could be required for both spontaneous and induced T1D in the BB rat. The aim of this study was to cross the DRF.f/f rat to BBDR and DR.lyp/lyp rats and produce recombinant sublines that could be assessed for both lymphopenia and diabetes and to estimate the number of independent genes on RNO4 that control spontaneous T1D.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

BBDR rats.

BBDR/Rhw rats (nonlymphopenic and diabetes resistant) used to generate the DRF.f/f (11) subcongenic strains had been sister/brother mated for 59 generations when used in these studies.

DR.lyp congenic rats.

Parental BBDR.BBDP-(D4Rhw17-SS99306861)(D4Rhw11-D4Rhw10)/Rhw rats were derived from animals with two independent recombination events developed by introgression of the DP gimap5 lymphopenia gene interval onto the DR genetic background through cyclic cross-intercross breeding (4). The parental line was analyzed after continuous backcrosses to DR rats and further fine mapping revealed additional DP DNA carried between markers D4Rhw17 (61.77 Mb) and SS99306861 (70.17 Mb). Care was taken to remove this DP interval through eight marker-assisted backcross generations with inbred BBDR/Rhw rats (Supplementary Fig. A1 ). The resulting congenic subline, defined as BBDR.BBDP-(D4Rhw11-D4Rhw10)/Rhw (Supplementary Table A), will hereafter be referred to as DR.lyp/lyp. These rats are currently in the 5th intercross generation.

DRF.f/f rats.

The congenic DRF.f/f rat [BBDR.F344-(D4Rat153-D4Rhw8).BBDP-(D4Rhw6-D4Rat62)/Rhw] is lymphopenic but protected from T1D (11). They are held in heterozygous sister/brother breeding and are currently in the 6th intercross generation.

Generation of the DRF.f/f congenic sublines.

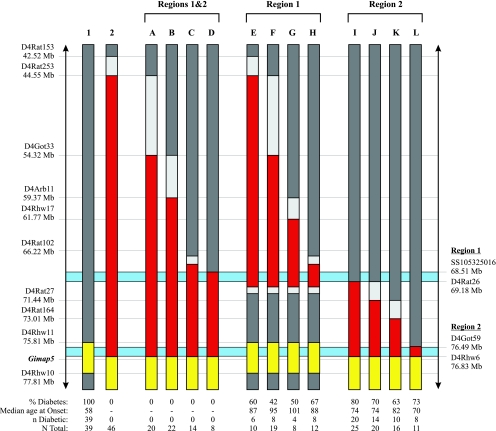

In all cases (DRF.A–L), the recombinant rat was crossed to a BBDR rat to produce additional animals and the offspring intercrossed to generate lymphopenic rats homozygous for the F344 DNA recombination that could be followed for the lymphopenia and diabetes phenotypes. DRF.A–D: To generate additional congenic sublines to narrow the 34 Mb F344 DNA interval in the DRF.f/f rat line, we established F2(DRF.f/f × BBDR) intercrosses and typed 13 genetic markers on RNO4 to identify recombinant offspring. Two separate recombination events reduced the proximal end of the F344 DNA fragment in the congenic DRF.f/f rat line and generated the DRF.A (flanked by DR DNA at D4Rat253 and D4Rhw8) and DRF.B (D4Got33-D4Rhw8) congenic sublines (Fig. 1, see Fig. 4 for location of D4Rhw8). Additional intercrosses within the DRF.A and DRF.B sublines generated the DRF.C (D4Rat102-D4Rhw8) and DRF.D (D4Rat102-D4Rhw8) sublines, respectively (Fig. 1). DRF.E–H: To generate recombination events that would reduce the proximal end of the F344 DNA fragment while retaining the gimap5 mutation, we established F2(DRF.f/f × DR.lyp/lyp) intercrosses. A recombination event indentified at D4Rat27 in a male rat generated the DRF.E (D4Rat153-D4Rat27) congenic subline (Fig. 1). Following crosses of the DRF.E male progenitor to a female BBDR, a recombination event was identified that generated the DRF.G (D4Arb11-D4Rat27) subline. Two separate recombination events identified in additional crosses of the F2(DRF.E × BBDR) to DR.lyp/lyp generated the DRF.F (D4Rat253-D4Rat27) and DRF.H (D4Rat102-D4Rat27) sublines (Fig. 1). DRF.I–L: Three separate recombination events identified in F2(DRF.f/f × BBDR) offspring again reduced the distal end of the F344 DNA fragment and generated the DRF.I (D4Rat102-D4Rhw8), DRF.K (D4Rat27-D4Rhw8), and DRF.L (D4Got59-D4Rhw8) congenic sublines. Following crosses of the DRF.f/f to the BBDR, a fourth recombination was identified that became the progenitor of the DRF.J (D4Rat26-D4Rhw8) subline (Fig. 1). Once established, the congenic sublines were subjected to high-resolution sequencing analysis to characterize breakpoints between genetic markers. The DR.lyp/lyp, DRF.f/f, DRF.C, and DRF.D congenic lines and sublines are currently being held in heterozygous sister/brother breeding and are available upon request.

Fig. 1.

Chromosome 4 map. The color code is as follows: red represents F344/F344, dark gray DR/DR, yellow DP/DP, and light gray is unknown. The light blue areas represent the 2 critical intervals; region 1 from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) SS105325016 to SSLP marker D4Rat26 containing the TCR Vβ and trypsin genes and region 2 from D4Got59 to D4Rhw6. All nondiabetic recombinant interval bearing rats (DRF.A–L) were tracked to between 145 and 312 days of age. See Fig. 4 for fine mapping of the DRF.H F344 DNA interval.

Housing.

Rats were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA) on a 12-h light/dark cycle with 24-h access to food (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water. Our institutional animal use and care committee approved all protocols. The University of Washington Rodent Health Monitoring Program was used to track infectious agents (11).

Blood lymphocyte phenotyping.

Between 25 and 30 days of age, two drops of tail vein blood were obtained for peripheral blood lymphocyte phenotyping. The cells were stained for the rat T cell receptor (TCR) using a R73 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) as well as monoclonal antibodies against CD4 (BD Biosciences) and CD8 (BD Biosciences) as previously described in detail (11). Samples were run on a BD Facscan (Beckton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) that had been compensated with both single-stained and unstained BBDR control samples. The proportion of R73+ cells was first determined among light scatter-gated mononuclear cells. Among the R73+ cells, we determined the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Results are expressed as median percent and interquartile range.

Diabetes diagnosis.

Starting at 40 days of age, lymphopenic rats were weighed daily (Sartorious, Edgewood, NY), and blood glucose concentration was measured (Ascensia Contour; Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) if the rat had not gained weight from the previous day. Diabetes was diagnosed as a glucose concentration >200 mg/dl for 2 consecutive days, after which insulin therapy was initiated.

Histology.

Sections (5 μm) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Insulitis was scored from two sections per rat by independent investigators unaware of the animals' genotype. The scoring was as follows: grade 0, no inflammatory cells. Grade 1, inflammatory cells around ducts and vessels only. Grade 2, inflammatory cells around the islets. Grade 3, inflammatory cells inside the islets without change in β-cell morphology. Grade 4, distorted β-cell morphology or islets devoid of β-cells. Grades 2–4 were always accompanied by inflammatory cells around ducts and vessels.

Genotyping chromosome 4.

Between 25 and 30 days of age, 2 mm tail snips were obtained, and DNA was isolated as detailed previously (13). The samples were diluted to 25 ng/μl in ddH20 and 2 μl of this genomic DNA used for simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) analysis as previously described in detail (11).

Whole genome scan.

At the N4 and N6 generations (Supplementary Fig. A), we genotyped 95 SSLPs, including D4Rat26 and D4Rat102, that covered the genome at an average interval of 20 cM to ensure that the genomic background of the new DR.lyp/lyp strain was fixed for BBDR. All SSLPs were amplified, and genotypes were determined by fluorescent genotyping on an ABI3730XL capillary sequencer as described (36).

Bioinformatics.

Candidate coding sequences were identified in regions 1 and 2 from: 1) known and reference gene sequences, 2) comparative analysis of rat, mouse, and human mRNA, rat spliced expressed sequence tags (EST), and gene prediction algorithms found at the University of California Santa Cruz Rat Genome Browser (UCSC) (http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html, assembly November 2004), or 3) previous studies (44). In all cases it was required that the candidate coding sequence have rat, mouse, or human mRNA or EST evidence along with identifiable AG/GT exon boundaries. SSLP markers for genotyping critical intervals were found at the Rat Genome Database (http://rgd.mcw.edu/). All other primers were designed using Primer3 (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi).

Sequencing.

To identify single nucleotide polymorphisms in candidate coding sequences (cSNPs) or that would be useful to characterize breakpoints (SNPs) in the DRF.f/f congenic sublines, we generated 900 to 1,500 bp PCR products of both the forward and reverse strand sequence from BBDR/Rhw (DR), BBDP/Rhw (DP), and F344/Rhw (F344) rat genomic DNA. Primer pairs spanned the full length of each individual exon including the flanking intronic sequences. Samples were sequenced using ABI BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Mix (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed on an ABI 3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the University of Washington Biochemistry Sequencing Core in Seattle, WA. The resulting genome survey sequences were submitted for official naming to GenBank at The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). All SNPs were submitted to the Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms at NCBI and assigned an individual NCBI assay ID (SS) identifier.

Statistical analysis.

Univariate analyses of lymphocyte phenotyping are shown as median percent (interquartile range) of R73 antibody-positive cells. In each new DRF subline group (A–D, E–H, and I–L) the nonparametric K-sample test on the equality of medians was used to test the null hypothesis that the K samples were drawn from populations with the same median percent-positive cells. When comparing medians between groups (DR.lyp/lyp, DRF.f/f, A–D, E–H, and I–L), we report P values with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. In the case of two samples, the χ2-test statistic was calculated with a continuity correction. Survival time in days until 25% of the rats developed T1D is presented for each genetic line along with the percentage of rats that become diabetic. Survival time to onset of T1D was calculated by the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 8 (StataCorp. 2003, Stata Statistical Software release 8; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA) used to generate the graphs. All two-tail statistical tests were judged with statistical significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Parental rats.

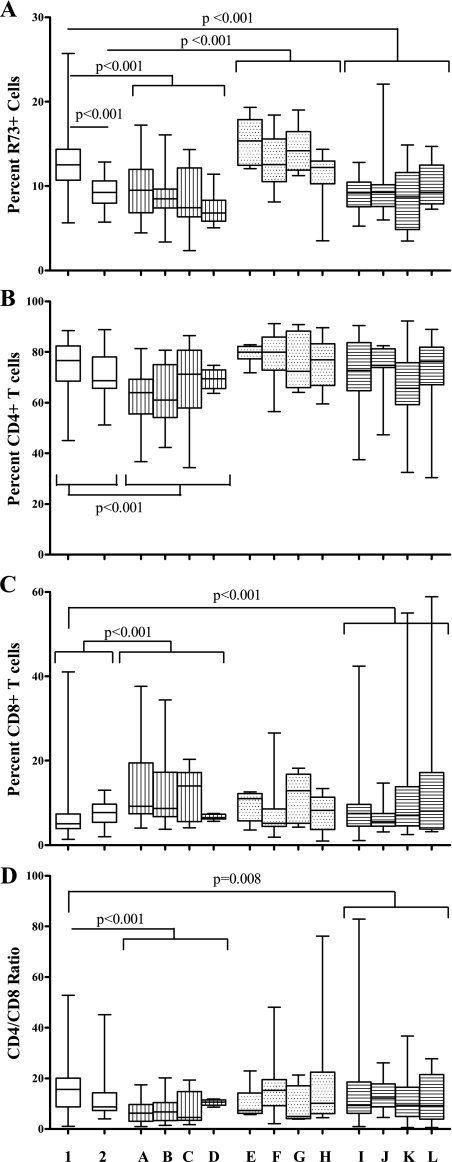

Congenic DR.lyp/lyp rats (Fig. 1, lane 1) were lymphopenic with 13% (11–14) [median percent (interquartile range)] R73+ cells (n = 80) (Fig. 2A). In contrast to DR.lyp/lyp rats, BBDR rats (not shown) had 60% (57–69) R73+ cells (P < 0.001). Among the R73+ cells, 75% (73–76) were CD4+ and 22% (21–24) were CD8+, the CD4/CD8 ratio being 3.4 (3.1–3.6, n = 75) (P = 0.99, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively, compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats). DRF.f/f rats (Fig. 1, lane 2) had fewer R73+ cells [9% (8–11)] compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). The median percent CD4+ (P = 0.64) and CD8+ (P = 0.20) cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.20) did not differ between DR.lyp/lyp and DRF.f/f rats (Fig. 2, B–D).

Fig. 2.

% R73+ TCR phenotyping. Column designations are as follows: 1, DR.lyp/lyp n = 80; 2, DRF.f/f n = 20; A, DRF.A n = 23; B, DRF.B n = 33; C, DRF.C n = 24; D, DRF.D n = 9; E, DRF.E n = 12; F, DRF.F n = 19; G, DRF.G n = 9; H, DRF.H n = 15; I, DRF.I n = 31; J, DRF.J n = 20; K, DRF.K n = 22; and L, DRF.L n = 11. Box plots indicate median and interquartile range with error bars indicating total range.

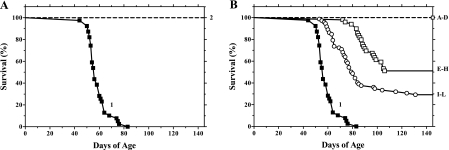

Of the 39 DR.lyp/lyp rats followed to diabetes onset, 25% developed T1D by 52 days of age, and all (100%) developed T1D by 83 days of age (Fig. 3). Lymphopenia and T1D in DR.lyp/lyp rats were associated with the 2 Mb of BBDP DNA, encompassing the gimap5 mutation, on RNO4 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Diabetes incidence as percent survival. Line designations are as follows: A: ▪ represent DR.lyp/lyp rats (1) (n = 39), while the dashed line represents DRF.f/f (2) (n = 73). B: ▪ again represents DR.lyp/lyp rats (1) (n = 39), dashed line represents DRF.A–D (n = 63), ○ represent the DRF. E–H (n = 55), and □ represent DRF.I–L (n = 72). All nondiabetic recombinant interval-bearing rats (DRF.A–L) were tracked to between 145 and 312 days of age.

Proximal reduction of the 34 mb F344 DNA fragment by 10–26 Mb (DRF.A–D).

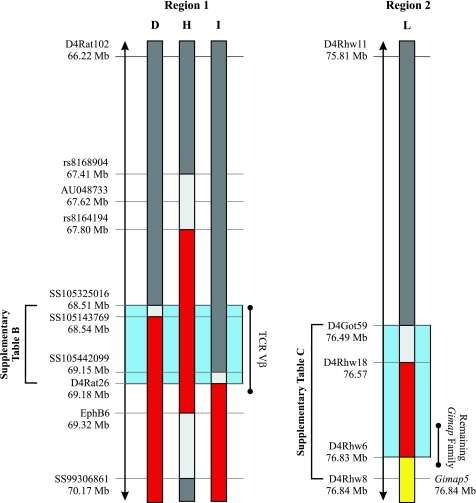

Recombination events generated in F2(DRF.f/f × BBDR) offspring reduced the proximal end of the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment in the DRF.f/f line by up to 26 Mb and generated four congenic sublines, DRF.A, B, C, and D (Fig. 1, lanes A–D). Further sequencing analysis revealed the DRF.D congenic subline was flanked by DR DNA at SS105325016 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fine mapping of critical intervals. The color code is identical to Fig. 1. Red represents F344/F344, dark gray DR/DR, yellow DP/DP, and light gray is unknown. Region 1, illustrated in light blue, is defined between the proximal flanking DR SNP, SS105325016, in the DRF.D subcongenic rat line and the proximal flanking F344 SSLP marker D4Rat26 in the DRF.I subcongenic rat line. Region 2, also illustrated in light blue, is defined by the interval between markers D4Got59 and D4Rhw6. Sequencing analysis of the genes within each critical interval can be found in Supplementary Tables B and C. AU048733 is the proximal Iddm14 marker. Regions 1 and 2 are scaled within themselves but not to each other.

While the median percent R73+ (P = 0.14) and CD4+ (P = 0.08) did not differ between the DRF.A, B, C, and D lines, a difference was observed in CD8+ cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.02 for both). DRF.A–D rats were all lymphopenic with 8% (7–11) R73+ cells (n = 89) when grouped (Fig. 2A). The percentage of R73+ cells did not differ from DRF.f/f rats (P = 0.60) but was significantly lower than in DR.lyp/lyp rats (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). DRF.A-D rats also differed from DR.lyp/lyp and DRF.f/f rats in CD4+ and CD8+ cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio (P < 0.001 for all) (Fig. 2, B–D).

All (64/64) DRF.A–D rats monitored to a median age of 196 (167–199) days showed complete protection from T1D (Fig. 3B). The DRF.D subline (Figs. 1, 4) retains the shortest F344 DNA recombinant interval with complete protection from diabetes (encompassing both regions 1 and 2) and defines the proximal border of region 1 (Fig. 4). Evaluation of pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration showed 97% of 375 islets inspected in five nondiabetic rats from DRF.B exhibited inflammatory cells only around ducts and vessels (grade 1) (Table 1). The data in these rats suggest that complete T1D protection is provided within the 8 Mb of F344 DNA conserved between SS105325016 (68.51 Mb) and D4Rhw6 (76.83 Mb) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of mononuclear cell infiltration in and around the pancreatic islets of the DRF.f/f sublines

| DRF.f/f Sublines | n | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Overall Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic rats | 6 | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 75 (92) | 4 |

| Nondiabetic rats | ||||||

| B | 5 | 363 (97) | 12 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| E | 4 | 51 (73) | 7 (10) | 0 (0) | 12 (17) | 1.6 |

| F | 9 | 408 (81) | 48 (10) | 1 (0) | 44 (9) | 1.6 |

| G | 4 | 66 (75) | 18 (20) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 1.3 |

| H | 4 | 204 (88) | 25 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 1.1 |

| I | 5 | 173 (76) | 29 (13) | 0 (0) | 25 (11) | 1.6 |

| J | 6 | 144 (73) | 31 (16) | 0 (0) | 22 (11) | 1.5 |

| K | 2 | 35 (74) | 7 (15) | 0 (0) | 5 (11) | 1.5 |

| L | 2 | 107 (87) | 7 (6) | 0 (0) | 9 (7) | 1.4 |

Infiltration of mononuclear cells (grades 1–4 as defined in research design and methods) is shown for the total number of islets observed in the number (n) of rats indicated. Number in parentheses is the percentage of islets falling into each category. Rats remaining nondiabetic were monitored for type 1 diabetes (T1D) to between 145 and 312 days of age, at which point the pancreas was removed for histology. The pancreas was removed at onset, between 64 and 169 days of age, from rats developing T1D.

Retaining 3 Mb F344 DNA at D4Rat26 (DRF.E–H).

Recombination events generated in F2(DRF.f/f × DF.lyp/lyp) offspring reduced the distal end of the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment in the DRF.f/f line to 28, 26, 11, and 3 Mb (Fig. 1, lanes E–H). The DRF.H subline is flanked by DR DNA at rs8168904 (67.41 Mb) and SS99306861 (70.17 Mb) and retains the shortest F344 DNA recombinant interval encompassing only region 1 (Figs. 1, 4).

The median percent R73+ (P = 0.09), CD4+ (P = 0.41), and CD8+ (P = 0.27) cells, the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.44), and the survival time to the onset of T1D (χ = 1.5, P = 0.68) did not differ between the DRF.E, F, G, and H lines. DRF.E–H rats were all lymphopenic with 13% (11–16) R73+ cells (n = 55) when grouped (Fig. 2A). The percentage of R73+ cells did not differ from DR.lyp/lyp rats (P = 0.99) but was significantly higher than in DRF.f/f rats (P < 0. 001) (Fig. 2A).

= 1.5, P = 0.68) did not differ between the DRF.E, F, G, and H lines. DRF.E–H rats were all lymphopenic with 13% (11–16) R73+ cells (n = 55) when grouped (Fig. 2A). The percentage of R73+ cells did not differ from DR.lyp/lyp rats (P = 0.99) but was significantly higher than in DRF.f/f rats (P < 0. 001) (Fig. 2A).

When taken together, T1D frequency in DRF.E–H rats was 53% (26/49), and 25% had developed T1D by 90 days of age (χ = 120, P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats) (Fig. 3B). Evaluation of pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration showed 82% of 891 islets inspected in 21 nondiabetic DRF.E–H rats were grade 1, 11% grade 2, and 7% grade 4 (Table 1). The results from these rats suggest that partial diabetes protection is located within the 3 Mb of F344 DNA encompassed by DRF.H (Figs. 1, 4).

= 120, P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats) (Fig. 3B). Evaluation of pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration showed 82% of 891 islets inspected in 21 nondiabetic DRF.E–H rats were grade 1, 11% grade 2, and 7% grade 4 (Table 1). The results from these rats suggest that partial diabetes protection is located within the 3 Mb of F344 DNA encompassed by DRF.H (Figs. 1, 4).

Retaining 340 kb F344 DNA between D4Rhw6 and D4Rhw2 (DRF.I–L).

Recombination events generated in F2(DRF.f/f × BBDR) offspring reduced the proximal end of the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment in the DRF.f/f line to 9, 8, 5, and 340 kb (region 2) (Fig. 1, lanes I–L). The DRF.L subline defines the region 2 interval (Figs. 1, 4).

The median R73+ (P = 0.92), CD4+ (P = 0.10), and CD8+ (P = 0.65) cells, the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.50), and the survival time to the onset of T1D (χ = 4.0, P = 0.26) did not differ between the DRF.I, J, K, and L lines. DRF.I–L rats were all lymphopenic with 9% (7–11) R73+ cells (n = 84) when grouped (Fig. 2A). The percentage of R73+ cells did not differ from DRF.f/f rats (P = 0.99) but was significantly lower than in DR.lyp/lyp rats (P < 0. 001) (Fig. 2A). DRF.I–L rats also differed from DR.lyp/lyp rats in CD8+ cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.01 and P = 0.008, respectively) (Fig. 2, B–D).

= 4.0, P = 0.26) did not differ between the DRF.I, J, K, and L lines. DRF.I–L rats were all lymphopenic with 9% (7–11) R73+ cells (n = 84) when grouped (Fig. 2A). The percentage of R73+ cells did not differ from DRF.f/f rats (P = 0.99) but was significantly lower than in DR.lyp/lyp rats (P < 0. 001) (Fig. 2A). DRF.I–L rats also differed from DR.lyp/lyp rats in CD8+ cells and the CD4/CD8 ratio (P = 0.01 and P = 0.008, respectively) (Fig. 2, B–D).

When taken together, T1D frequency in DRF.I–L rats was 72% (52/72), and 25% had developed T1D by 71 days of age (χ = 91.7, P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats) (Fig. 3). Evaluation of pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration showed 77% of 594 islets inspected in 15 nondiabetic DRF.I–L rats were grade 1, 12% grade 2, and 11% grade 4 (Table 1). The results from these rats suggest that partial diabetes protection can be explained by retention of 340 kb F344 DNA at the distal end of the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment between D4Got59 and D4Rhw6.

= 91.7, P < 0.001 compared with DR.lyp/lyp rats) (Fig. 3). Evaluation of pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration showed 77% of 594 islets inspected in 15 nondiabetic DRF.I–L rats were grade 1, 12% grade 2, and 11% grade 4 (Table 1). The results from these rats suggest that partial diabetes protection can be explained by retention of 340 kb F344 DNA at the distal end of the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment between D4Got59 and D4Rhw6.

Fine mapping of region 1 to 670 kb.

The proximal borders of both the DRF.D and DRF.I congenic sublines defined the complete region 1 interval (Fig. 4). The DRF.D rat line, flanked by DR DNA at SS105325016 (68.51 Mb), and with 0% T1D defined the proximal border of region 1 (Fig. 4). Further comparisons of the nondiabetic DRF.D rat line with the DRF.I congenic subline (with 80% T1D) showed that the leftmost F344 SSLP marker D4Rat26 (69.18 Mb), in the DRF.I rat line, defined the distal border of the region 1 interval (Fig. 4).

Coding sequence analysis of region 1.

Of the 35 potential candidate coding sequences identified in region 1, 31 were sequenced in DP, DR, and F344 (Supplementary Table B). Eight of these genes, tryX3, prss2, and TCR Vβs 6, 8.3, 8E, 12, 13, and 20, had nonsynonymous cSNPs between DP, DR, and F344. TCR Vβ6, 8.3, 8E, 12, 13, and 20 are six of 24 TCR variable β-genes located within the 670 kb region 1 interval on RNO4 (Supplementary Table B). tryX3 and prss2 are part of a family of 11 trypsin genes also located within the region 1 interval (Supplementary Table B). Of the eight genes, only Vβ8E, 12, and 13 had cSNPs that were unique to both DP and DR compared with F344 and the BN genome sequence (BN/Hsdmcwi) (UCSC) (Supplementary Table B).

Vβ8E had two coding sequence base pair deletions, one at position 260 of the mRNA, relative to the ATG start site, in DR and one at position 273 in DP, both of which independently resulted in a premature stop codon at amino acid position 94 (Supplementary Table B). One out of the four amino acid substitutions in Vβ12 resulted in a leucine-to-arginine substitution at position 69 in BB (DP/DR) (Supplementary Table B). Further sequencing analysis revealed that this amino acid substitution was not unique to BB but in fact shared by BDIX, BUF, LEW, and SHR (CrlBR). Vβ13 had a unique DP/DR coding sequence haplotype across six cSNPs from mRNA position 116 to 211, all of which produced amino acid substitutions in BB compared with F344 and the BN genome sequence (UCSC). Analysis of Vβ13 database sequences showed this DP/DR haplotype to be shared by LEW (AF213508), BUF (AF213507), and AS (AF213506). A unique T base pair insertion at position 256 in F344 resulted in a premature stop codon.

Coding sequence analysis of region 2.

Of the 13 potential candidate coding sequences identified in region 2, 12 were sequenced in DP, DR, and F344 (Supplementary Table C). Two of these genes, zfp467 and atp6v0e2, had nonsynonymous cSNPs between DP, DR, and F344. zfp467 is one of three zinc finger proteins located within the region 2 interval. atp6v0e2 is an H+ ATP vascular proton pump. zfp467 had two amino acid substitutions one of which was unique to DP: a serine-to-threonine at position 1726 relative to the ATP start site. atp6v0e2 had one amino acid substitution unique to DP: a serine to arginine at position 190.

DISCUSSION

In our previous study (11) we made the unexpected observation that 34 Mb of F344 DNA introgressed proximally to the gimap5 mutation on the DR.lyp/lyp congenic background retained lymphopenia but fully protected the rats from spontaneous T1D. The major finding in the present study was that the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment harbors at least two genetic factors affecting spontaneous T1D in the BB rat. The region 1 and 2 intervals were refined to 670 kb located between SS105325016 and D4Rat26 (68.51–69.18 Mb) and a 340 kb interval located between D4Got59 and D4Rhw6 (76.49–76.84 Mb), proximal to gimap5 (respectively). Refinement of the two regions allowed us to focus on coding sequence analysis of potential candidate genes within each interval.

In our approach of marker-assisted breeding (11, 16, 27, 31), all DRF.A–L sublines retained the gimap5 mutation (14, 27) and, as expected, were lymphopenic. Thus, it was of interest to observe that the severity of lymphopenia differed among groups. Comparative analysis of R73+ cells in the DRF.A–L congenic subline rats with the parental DRF.f/f (11) and the F344.lyp/lyp (31) congenic rat lines suggests that retention of DP DNA downstream of D4Rhw13 (77.41 Mb) results in the appearance of the severe lymphopenia phenotype. In addition, reappearance of partial diabetes penetrance in the DRF.I–L congenic sublines with low percent R73+ cells compared with the DR.lyp/lyp suggests that severe lymphopenia does not explain protection from T1D in DRF.f/f rats.

Generation of new recombinant congenic sublines through crosses of the DRF.f/f to BBDR and DR.lyp/lyp rats is a common and effective method for QTL dissection (1, 10, 35, 38, 39). In many cases, dissection of a single QTL has led to resolution of multiple individual contributing loci (10, 38, 39, 41). As such, our identification of two contributing T1D loci within the 34 Mb of F344 DNA was surprising but not unexpected. Interestingly, region 1 is encompassed within Iddm14, a locus associated with induction of diabetes in the BBDR rat by administration of poly-I:C and cytotoxic DS4.23 anti-ART2.1 (formerly RT6) monoclonal antibodies (29), and it is attractive to consider that Iddm14 could itself account for the regulation of spontaneous T1D. Indeed, mapping of the region 1 interval (68.51–69.18 Mb) to within the same 2.5 Mb location as Iddm14 (5) may narrow the Iddm14 QTL to the 670 kb between SS105325016 and D4Rat26.

The sequencing in region 1 detected several cSNPs that were polymorphic between DP, DR, and F344. As F344 DNA protects from T1D, our assumption was that DR and DP would share the same diabetogenic sequence. This was substantiated by the development of the DR.lyp/lyp congenic rat line with only 2 Mb DP DNA encompassing region 2. Recent analysis of induced T1D in DR × WF rats (Iddm14) has suggested TCR Vβ4 (5, 33), Vβ1, and Vβ13 (33) as candidate genes. The TCR Vβ gene sequences encode the variable segment of the extracellular β-polypeptide chain that, combined with the α-polypeptide chain, forms the TCR antigen-binding site crucial for T-cell signaling. Although sequence differences were found between BB and WF in these recent studies, we did not see them in our analyses of cSNPs in Vβ1 or Vβ4 between DP, DR, F344, and BN rats; however, we did detect nonsynonymous cSNPs where DP and DR were the same allele, but different from F344 and BN (UCSC) in Vβ8E, Vβ12, and Vβ13. The Vβ12 polymorphism was not unique to the BB rat. The Vβ13 gene would be expressed in DR and DP rats as well as in WF and BN rats (33) but not in F344 because of a truncation mutation at amino acid 89. While the amino acid sequence of DR would be identical to that of DP, these two rats differ from WF and BN with a protective Vβ13 haplotype (33). Furthermore, Vβ13 alleles have been shown to alter CD4/CD8 ratios on T cells that bear one or the other allele of Vβ13 (45). It is therefore tempting to speculate that Vβ13 expression on T cells, be it CD4 or CD8, may be important to T cell-mediated β-cell death in both spontaneous and induced T1D in rats. It would be of interest to examine T1D phenotypes in DRF f/f rats in response to poly I:C and cytotoxic DS4.23 anti-ART2.1 monoclonal antibodies (29) or viral infection to resolve the significance of TCR Vβ13 in both spontaneous and induced T1D. The amino acid substitutions in tryx3 and prss2 are of potential interest as trypsin genes have been associated with exocrine cell dysfunction and pancreatitis (23).

Region 2 also harbors several potential candidate genes. Zinc finger proteins have been associated with the regulation of immune response pathways (37) including the Toll-like receptor pathways, negative regulation of macrophage activation (25), and in transient neonatal diabetes (26). zfp467 itself has been characterized as a nuclear export protein and possible transcription regulator (40). While the function of the replication initiator, repin1, another zinc finger protein, remains unknown, variations in a 3′-untranslated triplet repeat have been associated with increased VLDL cholesterol, serum insulin, and severity of metabolic syndrome (22). Sequencing of the repin1 triplet T repeat showed DP with 27 repeats differing from both DR and F344 with 21 repeats (data not shown). As such, it cannot be excluded that repin1 may contribute to spontaneous BB rat T1D.

Interestingly, the absence of diabetes in the DRF.A–L congenic sublines rats did not correlate with normal pancreas histology. Only 1% of the islets in 145-day or older nondiabetic DRF.f/f congenic subline rats had grade 4 inflammation. Indeed, <20% of more than 1,900 islets inspected in nondiabetic DRF.f/f subline rats had islets affected by inflammation. This suggests that the F344 DNA introgressions fail to protect the pancreas from low-grade mononuclear cell infiltration around ducts and vessels. The genetic factors of F344 origin in regions 1 and 2 appear important for preventing β-cell death but not the underlying autoimmunity.

This initial analysis has made it possible for us to identify causal gene sequence variants that can now be analyzed in vitro to provide evidence for biological function(s) related to the diabetes phenotypes associated with genetic factors in either regions 1, 2, or both. It is possible that there are additional genetic factors controlling gene expression (transcription) that may be important for development of spontaneous T1D in the BB rat. There are numerous examples of noncoding mutations linked to levels of expression and/or disease mechanism. A single SNP located in a polyadenylation signal of human gimap5 was associated with IA-2 autoantibodies in T1D patients (42) for example. In addition, the role of microRNAs cannot be excluded although it is of interest to note that no microRNAs could be identified in either regions 1 or 2 via the miRNA track (miRBase) found at UCSC. These questions will be addressed in future investigations now that we know that there are at least two T1D loci. We will continue to generate additional DRF.f/f congenic sublines. We will also begin gene expression analysis and tissue expression distribution along with functional analysis of T cell subsets similar to previous reports (12, 30) with the aim to uncover the role of a TCR Vβ gene in the development of spontaneous T1D.

In summary, our results show that the 34 Mb F344 DNA fragment in the lymphopenic but diabetes-resistant DRF.f/f congenic rat line harbors at least two genetic factors affecting spontaneous T1D. Region 1 is a 670 kb interval encompassing the TCR Vβ and trypsin gene families, and region 2 is a 340 kb interval proximal to gimap5. Retaining F344 DNA at region 1 or 2 results in partial diabetes protection (47 and 28%, respectively) and delays time to onset while retaining F344 DNA at both regions 1 and 2 results in complete T1D protection. This suggests the interval is a compound QTL, although it remains to be determined if combining just these two regions recovers complete protection. The presence of F344 DNA at region 1 and 2 appears to protect the rats from severe insulitis but not from low-grade pancreatic mononuclear cell infiltration. Coding sequence analysis reveals TCR Vβ 8E, 12, and 13 as candidate genes in region 1 and znf467 and apt6v0e2 as candidate genes in region 2. Our results demonstrate that spontaneous T1D in the DR.lyp/lyp rat is controlled by at least two genetic loci 7 Mb apart on rat chromosome 4.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants AI-042380 (to Å. Lernmark, A. E. Kwitek, J. M. Fuller) and R01DK-066447 (to J. P. Mordes and E. P. Blankenhorn), as well as Center Grants DK-17047 and DK-32520, American Diabetes Association Grants 7-08-RA-106 (to J. P. Mordes) and 7-06-RA-14 (to E. P. Blankenhorn), by the Robert H. Williams Endowment at the University of Washington, and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Training Grant T32HL-007902* (R. A. Jensen). J. M. Fuller was also supported by The Diabetes Program at Lund University, the Medical Faculty at Lund University, Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet, and Diabetesföreningen Malmö.

*The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the NIH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Assistance with the BB rat colony by Paul Algeo, Diana Spencer, Bao Chau Tran, Alisha Wang, Lindsay Yokobe, and Karynne Tsuruda is much appreciated.

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: J. M. Fuller, Univ. of Washington, Dept. of Medicine, 1959 NE Pacific St., Box 357710, Seattle, WA 98195 (e-mail: jfuller@u.washington.edu).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Backdahl L, Ribbhammar U, Lorentzen JC. Mapping and functional characterization of rat chromosome 4 regions that regulate arthritis models and phenotypes in congenic strains. Arthritis Rheum 48: 551–559, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsocas CS, Gerasimidi-Vazeou A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 3, Suppl 3: 508–513, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieg S, Koike G, Jiang J, Klaff L, Pettersson A, MacMurray AJ, Jacob HJ, Lander ES, Lernmark A. Genetic isolation of iddm 1 on chromosome 4 in the biobreeding (BB) rat. Mamm Genome 9: 324–326, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieg S, Koike G, Jiang J, Klaff L, Pettersson A, MacMurray AJ, Jacob HJ, Lander ES, Lernmark Å. Genetic isolation of the Lyp region on chromosome 4 in the diabetes prone BioBreeding (BB) rat. Mamm Genome 9: 324–326, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankenhorn EP, Descipio C, Rodemich L, Cort L, Leif JH, Greiner DL, Mordes JP. Refinement of the Iddm4 diabetes susceptibility locus reveals TCRVbeta4 as a candidate gene. Ann NY Acad Sci 1103: 128–131, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankenhorn EP, Rodemich L, Martin-Fernandez C, Leif J, Greiner DL, Mordes JP. The rat diabetes susceptibility locus Iddm4 and at least one additional gene are required for autoimmune diabetes induced by viral infection. Diabetes 54: 1233–1237, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerna M Genetics of autoimmune diabetes mellitus. Wien Med Wochenschr 158: 2–12, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellerman KE, Like AA. Susceptibility to diabetes is widely distributed in normal class IIu haplotype rats. Diabetologia 43: 890–898, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettinger RA, Moustakas AK, Lobaton SD. Open reading frame sequencing and structure-based alignment of polypeptides encoded by RT1-Bb, RT1-Ba, RT1-Db, and RT1-Da alleles. Immunogenetics 56: 585–596, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber CR, Medrano JF. Dissection of a genetically complex cluster of growth and obesity QTLs on mouse chromosome 2 using subcongenic intercrosses. Mamm Genome 18: 635–645, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller JM, Kwitek AE, Hawkins TJ, Moralejo DH, Lu W, Tupling TD, Macmurray AJ, Borchardt G, Hasinoff M, Lernmark A. Introgression of F344 rat genomic DNA on BB rat chromosome 4 generates diabetes-resistant lymphopenic BB rats. Diabetes 55: 3351–3357, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold DP, Shaikewitz ST, Mueller D, Redd JR, Sellins KS, Pettersson A, Lernmark A, Bellgrau D. T cells from BB-DP rats show a unique cytokine mRNA profile associated with the IDDM1 susceptibility gene, Lyp. Autoimmunity 22: 149–161, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins T, Fuller J, Olson K, Speros S, Lernmark ADR. lyp/lyp bone marrow maintains lymphopenia and promotes diabetes in lyp/lyp but not in +/+ recipient DR.lyp BB rats. J Autoimmun 25: 251–257, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornum L, Romer J, Markholst H. The diabetes-prone BB rat carries a frameshift mutation in Ian4, a positional candidate of Iddm1. Diabetes 51: 1972–1979, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackerott M, Hornum L, Andreasen BE, Markholst H. Segregation of autoimmune type 1 diabetes in a cross between diabetic BB and brown Norway rats. J Autoimmun 10: 35–41, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob HJ, Pettersson A, Wilson D, Mao Y, Lernmark A, Lander ES. Genetic dissection of autoimmune type I diabetes in the BB rat. Nat Genet 2: 56–60, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaff LS, Koike G, Jiang J, Wang Y, Bieg S, Pettersson A, Lander E, Jacob H, Lernmark A. BB rat diabetes susceptibility and body weight regulation genes colocalize on chromosome 2. Mamm Genome 10: 883–887, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloting I, Schmidt S, Kovacs P. Mapping of novel genes predisposing or protecting diabetes development in the BB/OK rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 245: 483–486, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloting I, Van Den Brandt J, Kovacs P. Quantitative trait loci for blood glucose confirm diabetes predisposing and protective genes, Iddm4 and Iddm5r, in the spontaneously diabetic BB/OK rat. Int J Mol Med 2: 597–601, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloting I, van den Brandt J, Kuttler B. Genes of SHR rats protect spontaneously diabetic BB/OK rats from diabetes: lessons from congenic BB.SHR rat strains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283: 399–405, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloting I, Vogt L, Serikawa T. Locus on chromosome 18 cosegregates with diabetes in the BB/OK rat subline. Diabet Metab 21: 338–344, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kloting N, Wilke B, Kloting I. Triplet repeat in the Repin1 3′-untranslated region on rat chromosome 4 correlates with facets of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 23: 406–410, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landin-Olsson M, Borgstrom A, Blom L, Sundkvist G, Lernmark A. Immunoreactive trypsin(ogen) in the sera of children with recent-onset insulin-dependent diabetes and matched controls. The Swedish Childhood Diabetes Group. Pancreas 5: 241–247, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenzen S, Tiedge M, Elsner M, Lortz S, Weiss H, Jorns A, Kloppel G, Wedekind D, Prokop CM, Hedrich HJ. The LEW1AR1/Ztm-iddm rat: a new model of spontaneous insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 44: 1189–1196, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang J, Song W, Tromp G, Kolattukudy PE, Fu M. Genome-wide survey and expression profiling of CCCH-zinc finger family reveals a functional module in macrophage activation. PLoS ONE 3: e2880, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mackay DJ, Callaway JL, Marks SM, White HE, Acerini CL, Boonen SE, Dayanikli P, Firth HV, Goodship JA, Haemers AP, Hahnemann JM, Kordonouri O, Masoud AF, Oestergaard E, Storr J, Ellard S, Hattersley AT, Robinson DO, Temple IK. Hypomethylation of multiple imprinted loci in individuals with transient neonatal diabetes is associated with mutations in ZFP57. Nat Genet 40: 949–951, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacMurray AJ, Moralejo DH, Kwitek AE, Rutledge EA, Van Yserloo B, Gohlke P, Speros SJ, Snyder B, Schaefer J, Bieg S, Jiang J, Ettinger RA, Fuller J, Daniels TL, Pettersson A, Orlebeke K, Birren B, Jacob HJ, Lander ES, Lernmark A. Lymphopenia in the BB rat model of type 1 diabetes is due to a mutation in a novel immune-associated nucleotide (Ian)-related gene. Genome Res 12: 1029–1039, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markholst H, Eastman S, Wilson D, Andreasen BE, Lernmark A. Diabetes segregates as a single locus in crosses between inbred BB rats prone or resistant to diabetes. J Exp Med 174: 297–300, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin AM, Maxson MN, Leif J, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Blankenhorn EP. Diabetes-prone and diabetes-resistant BB rats share a common major diabetes susceptibility locus, iddm4: additional evidence for a “universal autoimmunity locus” on rat chromosome 4. Diabetes 48: 2138–2144, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore JK, Gold DP, Dreskin SC, Lernmark A, Bellgrau D. A diabetogenic gene prevents T cells from receiving costimulatory signals. Cell Immunol 194: 90–97, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moralejo DH, Park HA, Speros SJ, MacMurray AJ, Kwitek AE, Jacob HJ, Lander ES, Lernmark A. Genetic dissection of lymphopenia from autoimmunity by introgression of mutated Ian5 gene onto the F344 rat. J Autoimmun 21: 315–324, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mordes JP, Bortell R, Blankenhorn EP, Rossini AA, Greiner DL. Rat models of type 1 diabetes: genetics, environment, and autoimmunity. ILAR J 45: 278–291, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mordes JP, Cort L, Norowski E, Leif J, Fuller JM, Lernmark A, Greiner DL, Blankenhorn EP. Analysis of the rat Iddm14 diabetes susceptibility locus in multiple rat strains: identification of a susceptibility haplotype in the Tcrb-V locus. Mamm Genome 20: 162–169, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mordes JP, Poussier P, Rossini AA, Blankenhorn EP, Greiner DL. Rat models of type 1 diabetes: genetics, environment, and autoimmunity. In: Animal Models of Diabetes: Frontiers in Research, edited by Shafrir E. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2007, p. 1–39.

- 35.Moreno C, Kaldunski ML, Wang T, Roman RJ, Greene AS, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW Jr. Multiple blood pressure loci on rat chromosome 13 attenuate development of hypertension in the Dahl S hypertensive rat. Physiol Genomics 31: 228–235, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno C, Kennedy K, Andrae JW, Jacob HJ. Genome-wide scanning with SSLPs in the rat. Meth Mol Med 108: 131–138, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moroy T, Zeng H, Jin J, Schmid KW, Carpinteiro A, Gulbins E. The zinc finger protein and transcriptional repressor Gfi1 as a regulator of the innate immune response. Immunobiology 213: 341–352, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruf C, Carosone-Link P, Springett J, Bennett B. Confirmation and genetic dissection of a major quantitative trait locus for alcohol preference drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1613–1621, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saad Y, Yerga-Woolwine S, Saikumar J, Farms P, Manickavasagam E, Toland EJ, Joe B. Congenic interval mapping of RNO10 reveals a complex cluster of closely-linked genetic determinants of blood pressure. Hypertension 50: 891–898, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saijou E, Itoh T, Kim KW, Iemura S, Natsume T, Miyajima A. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the zinc finger protein EZI is mediated by importin-7-dependent nuclear import and CRM1-independent export mechanisms. J Biol Chem 282: 32327–32337, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samuelson DJ, Hesselson SE, Aperavich BA, Zan Y, Haag JD, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Mau B, Chen KS, Baynes C, Khaw KT, Luben R, Perkins B, Shah M, Pharoah PD, Dunning AM, Easton DF, Ponder BA, Gould MN. Rat Mcs5a is a compound quantitative trait locus with orthologous human loci that associate with breast cancer risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6299–6304, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin JH, Janer M, McNeney B, Blay S, Deutsch K, Sanjeevi CB, Kockum I, Lernmark A, Graham J, Arnqvist H, Bjorck E, Eriksson J, Nystrom L, Ohlson LO, Schersten B, Ostman J, Aili M, Baath LE, Carlsson E, Edenwall H, Forsander G, Granstrom BW, Gustavsson I, Hanas R, Hellenberg L, Hellgren H, Holmberg E, Hornell H, Ivarsson SA, Johansson C, Jonsell G, Kockum K, Lindblad B, Lindh A, Ludvigsson J, Myrdal U, Neiderud J, Segnestam K, Sjoblad S, Skogsberg L, Stromberg L, Stahle U, Thalme B, Tullus K, Tuvemo T, Wallensteen M, Westphal O, Aman J. IA-2 autoantibodies in incident type I diabetes patients are associated with a polyadenylation signal polymorphism in GIMAP5. Genes Immun 8: 503–512, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simmonds S, Mason D. Induction of autoimmune disease by depletion of regulatory T cells. Curr Protoc Immunol 15: Unit 15.12, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Smith LR, Kono DH, Theofilopoulos AN. Complexity and sequence identification of 24 rat V beta genes. J Immunol 147: 375–379, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stienekemeier M, Hofmann K, Gold R, Herrmann T. A polymorphism of the rat T-cell receptor beta-chain variable gene 13 (BV13S1) correlates with the frequency of BV13S1-positive CD4 cells. Immunogenetics 51: 296–305, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallis RH, Wang K, Dabrowski D, Marandi L, Ning T, Hsieh E, Paterson AD, Mordes JP, Blankenhorn EP, Poussier P. A novel susceptibility locus on rat chromosome 8 affects spontaneous but not experimentally induced type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 56: 1731–1736, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yokoi N Identification of a major gene responsible for type 1 diabetes in the Komeda diabetes-prone rat. Exp Anim 54: 111–115, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.