Abstract

Decline in renal function is directly related to cardiovascular mortality. However, traditional risk factors do not fully account for the high mortality in these patients. Activated vitamin D, a hormone produced by the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney, appears to have beneficial effects beyond suppressing parathyroid hormone. However, activated vitamin D can also cause hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Newer agents such as vitamin D receptor activators (VDRAs, e.g., paricalcitol) suppress PTH with reduced risk of hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. Recent evidence from animal and preliminary human studies supports an association between VDRAs and reduced risk of CVD deaths, irrespective of PTH levels. New pathways of vitamin D regulation have also been discovered, namely the roles of fibroblast growth factor-23 and klotho. Although tremendous work has been done to advance our understanding of the effects of vitamin D in health and CKD, more investigations and randomized trials need to be performed to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of this effect.

Keywords: vitamin D, paricalcitol, calcitriol, CKD, dialysis, FGF-23, klotho, hyperparathyroidism

Background

Mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is inversely related to renal function (1). The high mortality in this population is primarily due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and infection (2). A frustrating aspect of CVD outcome in CKD patients is that traditional risk factors explain only half of all causes of mortality (3). Researchers have intensified efforts to focus on non-traditional risk factors, such as vitamin D. The National Kidney Foundation clinical practice guidelines for bone and mineral metabolism focus on the use of vitamin D to suppress elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) in CKD (4). It is known that with worsening renal function there is progressive decline in the activity of 1α-hydroxylase, the enzyme critical in converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol). This parallels worsening of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Vitamin D treatment with vitamin D receptor activators (VDRAs) such as calcitriol (Rocaltrol®), paricalcitol (Zemplar®), or doxercalciferol (Hectorol®) has been shown to reduce mortality in dialysis and non-dialysis (CKD-D and CKD-ND) patients. Although indirect, recent evidence indicates that VDRAs may play an important role in influencing these outcomes, beyond their ability to suppress PTH. These data have been supported by animal studies and small physiologic studies in humans. The following review is in no way exhaustive on this topic, as this field has grown enormously in recent years. Since 1973 alone, more than 300 review articles have been indexed on Pubmed since 1973 on vitamin D and kidney disease. More than half of these were published in the past three years, a testament to the momentum of recent interest in this topic. However, this review will give an overview of important clinical and animal studies related to VDRA in CKD. The reader is referred to the previous issue of this journal on the role of vitamin D in the management of secondary hyperparathyroidism (5).

New Insights in Regulation of Vitamin D in CKD

The structure of vitamin D was described by Adulf Windaus in 1927 (6). Subsequently, Slatopolsky et al. reported the role of activated vitamin D in suppressing secondary hyperparathyroidism (7). Brunette et al. discovered that calcitriol is synthesized in the proximal convoluted tubule of the kidney (8). Further actions of vitamin D were better characterized with the discovery of vitamin D receptor and VDR knockout mice (9). Recently, characterization of the klotho gene and fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) have added substantially to our understanding of the regulation of vitamin D.

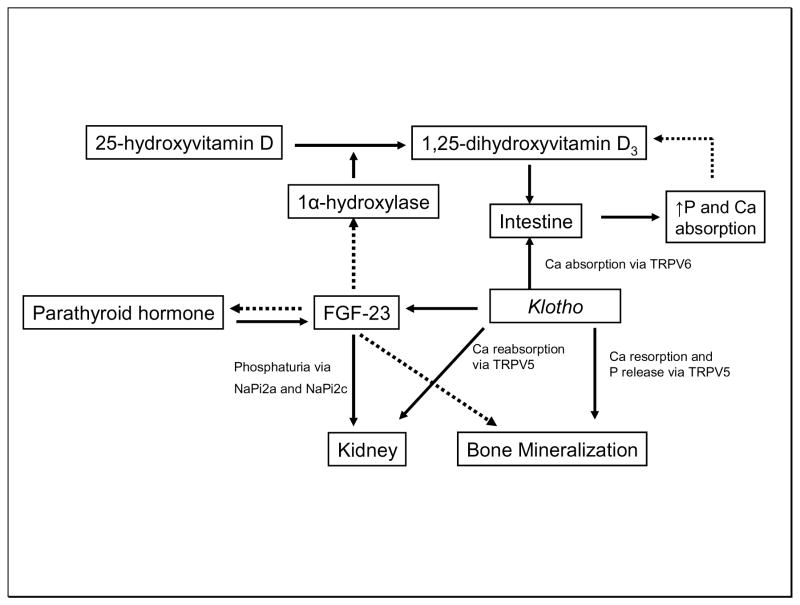

Klotho is predominantly expressed in the distal tubule of the kidney (11). It can act as a circulating form or as a hormone. It functions as a cofactor for the stimulation of the FGF-23 receptor. It also co-localizes with epithelial calcium channel transient receptor potential vallinoid-5 (TRPV5). A mutation of the klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling CKD with changes normally associated with accelerated aging. The syndrome is also characterized by hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and elevated calcitriol (10). Mice overexpressing the klotho gene age slowly through a mechanism that involves insulin and oxidant stress resistance. FGF-23 is a 30kDa protein primarily synthesized by osteocytes. FGF-23 controls renal phosphate excretion by regulating renal sodium-dependent phosphate co-transporters (NaPi2a and NaPi2c). Klotho binds to FGF-23 receptors and permits various cells to respond to FGF-23, thus acting as a cofactor. Furthermore, klotho protein also functions as a humoral factor and regulates insulin-like growth factor-1 and Wnt (11). Recent genetic studies with FGF-23 and klotho knockout mice noted extensive vascular and soft tissue calcification (12). Interestingly, FGF-23 is a counter-regulatory hormone for vitamin D (13). Levels of FGF-23 rise after administration of vitamin D, reducing renal formation of calcitriol through its action on the 1α-hydroxylase gene. Furthermore, FGF-23 knockout mice have extremely high serum phosphorus and calcitriol levels along with soft-tissue calcification. FGF-23 also interacts with PTH and is a negative regulator of PTH expression (14). Conversely, PTH stimulates FGF-23 secretion from the bone. Liu et al. proposed that the klotho-FGF-23 axis operates as follows. With progression of CKD, FGF-23 suppresses PTH expression and also inhibits 1α-hydroxylase activity, which results in decreased calcitriol, thus reducing phosphorus levels (15).

Human studies have been encouraging. Fliser et al. measured FGF-23 levels in 227 CKD-ND patients and followed them for 53 months. The authors found that c-terminal and intact FGF-23 independently predicted CKD progression (defined by doubling of serum creatinine) (16). Similarly, Gutierrez et al. performed a nested case-control study in incident dialysis patients. c-terminal FGF-23 levels (median or by quartile) were significantly higher at the initiation of dialysis in patients who died compared to controls (17). Clearly, more studies are needed to delineate the details of this fascinating new pathway. More extensive reviews on these topics are available (18, 19). A schematic diagram of the regulation of vitamin D by FGF-23 and klotho is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Interplay among vitamin D, klotho, and fibroblast growth factor-23 in chronic kidney disease. Solid arrow indicates stimulatory action, and broken arrow indicates inhibitory action. FGF-23: Fibroblast growth factor; Ca: calcium; P: Phosphorus; NaPi: Sodium-dependent phosphate co-transporter; TRPV: transient receptor potential vallinoid.

Recent Clinical Studies in CKD Patients

Recent basic science and human studies suggest that VDRAs, independent from their effect on PTH, influence mortality. Furthermore, observational studies support that the newer VDRAs (paricalcitol and doxercalciferol) have better outcomes than traditional therapy with calcitriol. This may be due to the tendency of calcitriol to cause hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. Alternatively, VDRAs may act on different biologic targets.

Influence of Vitamin D on Mortality in CKD

In CKD-D patients, there has been epidemiological evidence supporting the role of vitamin D in reducing the risk of CVD deaths. Shoji et al. showed in a small observational study that patients taking alfacalcidol had reduced risk of CVD death compared to patients who were not on vitamin D (20). Tentori et al. published similar findings in a larger cohort treated with VDRA (21). Another study showed reduced mortality even in incident dialysis patients treated with VDRA (22). Is one VDRA better than the other? Animal studies (see below) and epidemiologic studies have shown that paricalcitol may have an advantage over calcitriol. Teng et al. reported 16–26% lower risk of death in patients receiving paricalcitol versus calcitriol, irrespective of PTH suppression or mineral status (23, 24). In contrast, a meta-analysis by Palmer et al. found no beneficial effects on mortality or vascular calcification in patients with CKD who had received VDRA (25). These authors concluded that the “beneficial effects of VDRAs on patient-level outcomes are unproven. The value of vitamin D treatment for people with CKD remains uncertain.” It is important to note, however, that the individual studies included in their meta-analysis were not designed to address the CVD outcome. Furthermore, the authors acknowledged marked heterogeneity across studies. For example, they combined studies in adults with those in pediatric dialysis-dependent and non-dialysis-dependent patients with CKD. As in any meta-analysis, the conclusions are dependent upon the design and outcomes of the individual studies (26).

Evidence for the beneficial effect of VDRA in CKD-ND is emerging. Kovesdy et al. reported a single-center, non-randomized, observational study of 520 male US veterans with CKD-ND and mean estimated glomerular filtration rate 30.8 ml/min. The authors reported an association of calcitriol treatment with reduced mortality after a median follow-up of 2.1 years (27). A separate study reached a similar conclusion (28). Though these studies are small and more large studies are needed, the findings are consistent.

Pleotropic Effects of Vitamin D on Different Organ Systems

Role of Vitamin D in vascular calcification

Patients on dialysis have a high prevalence of vascular calcification (29). Several small observational studies have reported the association of vitamin D levels with vascular calcification (30–33). The hypotheses were that vitamin D enhances calcium and phosphorus absorption from the intestine and increases the calcium phosphorus (Ca x P) product. However, a cross-sectional study in high-risk CVD patients showed an inverse relationship between vitamin D levels and extent of vascular calcification (34). It is possible that calcification is VDRA dose-dependent, with lower doses suppressing calcification and higher doses stimulating calcification. Vitamin D has been shown to inhibit calcification by inhibiting type 1 collagen production (35) and suppressing core-binding factor-α1 (36). Type 1 collagen serves as scaffolding for calcium deposition. Core-binding factor-α1 enhances deposition of type 1 collagen. Vitamin D also stimulates Matrix Gla protein, a potent inhibitor of vascular calcification. Matthew et al. studied the effect of calcitriol and paricalcitol on aortic calcification in a mouse model of CKD and adynamic bone disease (LDL receptor knockout mice fed with high-fat diet). The authors found that in doses sufficient to correct secondary hyperparathyroidism, calcitriol and paricalcitol protected against aortic calcification by suppressing osteoblastic gene expression in the aorta. However, higher doses stimulated aortic calcification (37). One caveat is the presence of adynamic bone disease in this rat model, an exclusion criterion for VDRA use in clinical practice. Another study evaluated the effect of calcitriol and paricalcitol on vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) calcification in vitro and in vivo in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Calcitriol, but not paricalcitol, increased VSMC calcification independent of mineral levels. This increase in calcification paralleled an increase in receptor activator for nuclear kappa B (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) expression. Treatment of rats with hypercalcemic doses of calcitriol and paricalcitol caused significantly higher pulse pressure in the calcitriol group, probably from extensive calcification in the arteries. This increase in calcification was not seen in arteries of animals treated with paricalcitol despite having levels of serum calcium and phosphorus similar to animals treated with calcitriol. Furthermore, the decreases in serum PTH levels were similar in both treatments (38). Noonan et al. evaluated the differential role of paricalcitol and doxercalciferol in the pathogenesis of aortic calcification in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. The authors found that high doses of doxercalciferol caused increased aortic calcium and phosphorus content and increased pulse wave velocity compared to sham- or paricalcitol-treated rats at week 6. There was no significant difference in Ca, P, or Ca X P between the two active agents (39). Thus, differential effects of VDRA may influence clinical outcome.

Though calciphylaxis, a feared complication of dialysis, has been associated with vitamin D use (40), a recent systematic review of calciphylaxis did not show this relationship between VDRA and calciphylaxis (41).

Role of Vitamin D on Heart Function

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a common complication of CKD and an independent risk factor for mortality (42). There is growing evidence that vitamin D homeostasis may play a critical role in cardiac function and that disturbances in vitamin D homeostasis may lead to the development of hypertension. Mortality in patients with congestive heart failure is independently associated with vitamin D deficiency (43). VDRKO mice have LVH and activation of the renin-angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) (44). Further, paricalcitol lowered LV mass and improved cardiac function in Dahl salt-sensitive rats (45). Another study found similar cardiac phenotype with 1α-hyroxylase knockout mice and reversal of the pathology after administration of activated vitamin D. The authors went on to show that the underlying mechanism appears to be activation of RAAS (46, 47). A study in uninephrectomized ApoE knockout mice (a model that promotes atherosclerosis) found that paricalcitol and calcitriol maintained cardiac microvascularity (48). In humans, vitamin D has been associated with improved cytokine profile (decrease in pro-inflammatory TNFα and increase in anti-inflammatory IL-10) in patients with congestive heart failure and regression of cardiac hypertrophy in dialysis patients (49, 50). In light of these findings, a randomized trial is under way to address whether paricalcitol reduces LVH in CKD-ND patients. The Paricalcitol benefit in Renal failure Induced cardiac MOrbidity (PRIMO) study aims at evaluating effects of oral paricalcitol (compared to placebo) on progression or regression of LVH in 220 subjects with Stage 3B/4 CKD, as assessed by comparing changes in LV Mass Index (LVMI) measured by sequential cardiac MRI. The expected completion date is June 2010 (51).

Role of Vitamin D in Proteinuria

Levin et al. evaluated the status of vitamin D in the SEEK cohort. They found that low 25-vitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 were independently associated with increased albuminuria in CKD-ND patients. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 was found to be an important intermediary between vitamin D deficiency and albuminuria (52). A report on the efficacy of VDRA on proteinuria was recently published. Agarwal et al. found an antiproteinuric effect of oral paricalcitol in a CKD cohort (53). The same investigators evaluated the influence of paricalcitol in a randomized pilot trial in CKD-ND proteinuric patients. Twenty-four patients were randomly allocated to three equal groups to receive 0, 1, or 2μg paricalcitol orally for one month. The patients underwent assessment of endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated vasodilation, C-reactive protein, and urine albumin excretion. At one month, there was no change in flow-mediated vasodilation among the groups. C-reactive protein was lower in the paricalcitol treatment group; there was a pronounced effect of 2μg paricalcitol on albuminuria independent of renal function, ambulatory blood pressure, or PTH. Thus, reduction in albuminuria and inflammation may be independent of paricalcitol’s effect on hemodynamics and PTH suppression (54). In separate animal studies, vitamin D was shown to ameliorate glomerulosclerosis, glomerular hypertrophy, podocyte hypertrophy, mesangial proliferation, and interstitial fibrosis (55–58). To validate human findings, a larger placebo-controlled study is ongoing. The Selective VItamin D receptor acTivator (Paricalcitol) for Albuminiuria Lowering Study (VITAL) is a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center study aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of paricalcitol for reducing albuminuria in type 2 diabetic nephropathy subjects who are already being treated with RAAS inhibitors (59). The study plans to enroll 258 subjects, with completion in August 2009.

Role of Vitamin D in Immune regulation

The second most common cause of death in dialysis patients is infection (60). Since the discovery of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors on human leukocytes, immunologists have been intrigued by the relationship between vitamin D and leukocyte regulation (61). The pivotal role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of bacterial and mycobaterial infection is becoming clearer. Liu et al. showed that vitamin D activates Toll-like receptor 2/1 in human monocytes and induces antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin when exposed to extracts of M. tuberculosis (62). Though human studies are still pending, this area of research appears to be promising.

Role of Vitamin D in Cancer Prevention

Dialysis patients appear be to at higher risk for cancer (63). In recent years, activated vitamin D has been shown to inhibit proliferation, reduce invasiveness and angiogenesis, induce apoptosis, and inhibit differentiation in animal and preclinical studies. A synergistic effect between chemotherapy and radiation has been reported. However, extremely high doses of calcitriol are required to achieve a antineoplastic effect, resulting in hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. Phase I and Phase II studies have been encouraging, and a randomized trial in prostate cancer is ongoing. The molecular mechanism appears to be related in part to the interaction between calcitriol and retinoid X receptor; this heterodimer in turn modulates genes downstream (64, 65). Although studies are lacking to address cancer prevention or reduction in the dialysis population, it is conceivable that this drug and the newer VDRAs may have beneficial effects on cancer prevention and may retard the progression of cancer in CKD patients.

Role of Vitamin D in Coagulation Homeostasis

Recently published in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the role of vitamin D in coagulation homeostasis. An in vitro study showed that calcitriol possesses anti-coagulant properties in cultured monocytic cells (66). Another in vivo study evaluated vitamin D’s role using a VDR knockout (VDRKO) mouse model. In VDRKO mice platelet aggregation was enhanced, antithrombin (in liver) and thrombomodulin (aorta, liver and kidney) gene expression was down-regulated, and tissue factor mRNA expression was up-regulated in liver and kidney. Interestingly, VDRKO mice showed exacerbated multi-organ thrombus formation after exogenous lipopolysaccharide injection (a potent exogenous pyrogen that resembles endotoxin). The authors concluded that activation of VDR may have an antithrombotic effect (67). However, human data on the role of vitamin D in coagulation physiology are lacking.

New Evidence of the Role of Vitamin D in Parathyroid Regulation

The resistance of the parathyroid gland to calcitriol was recently elucidated by Dusso et al. In this rat model of nodular hyperplasia, the most severe form of secondary hyperparathyroidism, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), was activated by tumor growth factorα (TGFα). This was in turn associated with enhanced proliferation rate and reduced levels of VDR mRNA. Thus, EGFR activation may cause hyperplastic growth and VDR reduction, thereby causing resistance to the antiproliferative and PTH-suppressive properties of calcitriol therapy (68). Further work by the same group showed amelioration of markers of genomic instability in early secondary hyperparathyroidism by calcitriol, thereby preventing the switch from diffuse to nodular growth in the parathyroid gland (69).

Role of 25-vitamin D in CKD

The prevalence of 25-vitamin D deficiency increases with progression of CKD and approaches 80% in stage 5 CKD patients (70, 71). Although repletion with high-dose ergocalciferol (20,000 units/week × 9 months) is considered safe, it achieves the desired level in only about 50% of hemodialysis patients (72). A small randomized trial found that 50,000 units of cholecalciferol weekly for 12 weeks was safe and effective in repleting 25-vitamin D levels in stage 3 and 4 CKD patients (73). This difference could be due to the severity of CKD disease or differential impact of ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol by CKD stage. Dose-finding studies in CKD-D are needed.

Vitamin D deficiency has also been linked to increased prevalence of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, obesity, CVD, and albuminuria (74–78). Small studies in humans have shown improvement in some of these phenotypes with administration of vitamin D (79). Interestingly, atorvastatin increases serum vitamin D levels. This suggests that vitamin D plays a role in the beneficial non-lipid-lowering actions of atorvastatin, a drug shown to improve CVD outcomes in non-CKD patients (80).

Efficacy of Combination of VDRA and Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitor in CKD

In a study by Mizobuchi et al., rats made uremic by 5/6 nephrectomy were treated with vehicle, enalapril, paricalcitol, or enalapril+paricalcitol. A group of normal rats served as controls. The authors reported that combination treatment retarded the progression of renal disease via mediation of the TGF-beta signaling pathway, and the effect was amplified by lowering blood pressure via RAAS blockade (81). The same investigators reported greater amelioration of cardiac oxidative injury in uremic rats exposed to combination treatment than to either drug alone (82). Thus it could be that use of RAAS blockers has a beneficial effect in reducing CVD and CKD progression. Human studies are needed to validate these findings.

Race and Vitamin D in CKD

It is well established that African-Americans with CKD-ND have poorer survival overall than Caucasian patients. However, African-Americans do have improved survival after initiating dialysis when compared to their Caucasian counterparts (83). In CKD-ND patients, Gutierrez et al. found higher prevalence of disordered mineral metabolism: significantly higher PTH, serum calcium, and serum phosphorus levels and significantly lower 25-vitamin D levels (84). Furthermore, the same group evaluated the effect of vitamin D on mortality by race in a prospective cohort of incident dialysis patients. The authors found that African-American patients who were not treated with VDRA had 35% higher mortality than untreated Caucasian patients. However, African-Americans had significantly lower one-year mortality compared to Caucasians in the VDRA-treated group. There was a significant interaction between race and VDRA treatment and survival, and mortality was no longer different after adjusting for VDRA treatment. The authors concluded that VDRA treatment may explain the racial differences in survival among dialysis patients (85). In summary, vitamin D may play a role in racial differences in mortality seen in dialysis patients.

Future Directions

The time has come to move beyond association studies. A number of questions need to be resolved with randomized trials and hard end-points, including mortality, CVD events, stroke, dialysis initiation, etc. Should all CKD patients receive low-dose VDRA, even those with low PTH levels? Should paricalcitol be preferentially used over calcitriol in all CKD patients? Will vitamin D combination therapy with RAAS inhibitors have a beneficial effect in CKD patients? We venture to suggest that there may be no ongoing randomized trials of VDRA in CKD addressing hard end-points because of apathy from investigators and funding agencies’ reluctance to conduct studies with the potential to reveal negative outcomes (86).

Acknowledgments

Support

Dr. Patel was supported by T32- DK07527-23

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tejas Patel, Renal Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Ajay K. Singh, Director, Dialysis Service, Renal Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Anavekar NS, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1285–1295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Accessed August 15, 2008]; http://www.usrds.org/2007/pdf/06_hosp_morte_07.pdf.

- 3.Zoccali C, Tripepi G, Mallamaci F. Predictors of cardiovascular death in ESRD. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:358–362. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:S1–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin KJ, Gonzalez EA. Vitamin D analogs: actions and role in the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf G. The discovery of vitamin D: the contribution of Adolf Windaus. J Nutr. 2004;134:1299–1302. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Thielan J, Horst R, Harter H, Martin KJ. Marked suppression of secondary hyperparathyroidism by intravenous administration of 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol in uremic patients. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:2136–2143. doi: 10.1172/JCI111639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunette MG, Chan M, Ferriere C, Roberts KD. Site of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 synthesis in the kidney. Nature. 1978;276:287–289. doi: 10.1038/276287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christakos S, Dhawan P, Liu Y, Peng X, Porta A. New insights into the mechanisms of vitamin D action. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:695–705. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuro-o M. Klotho as a regulator of oxidative stress and senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:233–241. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, et al. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1305–1315. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krajisnik T, Bjorklund P, Marsell R, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:125–131. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu S, Gupta A, Quarles LD. Emerging role of fibroblast growth factor 23 in a bone-kidney axis regulating systemic phosphate homeostasis and extracellular matrix mineralization. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:329–335. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3281ca6ffd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fliser D, Kollerits B, Neyer U, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2600–2608. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Mortality among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Memon F, El-Abbadi M, Nakatani T, Taguchi T, Lanske B, Razzaque MS. Does Fgf23-klotho activity influence vascular and soft tissue calcification through regulating mineral ion metabolism? Kidney Int. 2008;74:566–570. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres PU, Prie D, Molina-Bletry V, Beck L, Silve C, Friedlander G. Klotho: an antiaging protein involved in mineral and vitamin D metabolism. Kidney Int. 2007;71:730–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoji T, Shinohara K, Kimoto E, et al. Lower risk for cardiovascular mortality in oral 1alpha-hydroxy vitamin D3 users in a haemodialysis population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:179–184. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melamed ML, Eustace JA, Plantinga L, et al. Changes in serum calcium, phosphate, and PTH and the risk of death in incident dialysis patients: a longitudinal study. Kidney Int. 2006;70:351–357. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tentori F, Hunt WC, Stidley CA, et al. Mortality risk among hemodialysis patients receiving different vitamin D analogs. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1858–1865. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng M, Wolf M, Lowrie E, Ofsthun N, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R. Survival of patients undergoing hemodialysis with paricalcitol or calcitriol therapy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:446–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teng M, Wolf M, Ofsthun MN, et al. Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: a historical cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1115–1125. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer SC, McGregor DO, Macaskill P, Craig JC, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF. Meta-analysis: vitamin D compounds in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:840–853. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-12-200712180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thadhani R. Activated vitamin D sterols in kidney disease. Lancet. 2008;371:542–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovesdy CP, Ahmadzadeh S, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of activated vitamin D treatment and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:397–403. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoben AB, Rudser KD, de Boer IH, Young B, Kestenbaum B. Association of oral calcitriol with improved survival in nondialyzed CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1613–1619. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478–1483. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milliner DS, Zinsmeister AR, Lieberman E, Landing B. Soft tissue calcification in pediatric patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1990;38:931–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldsmith DJ, Covic A, Sambrook PA, Ackrill P. Vascular calcification in long-term haemodialysis patients in a single unit: a retrospective analysis. Nephron. 1997;77:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000190244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berlyne GM, Mallick NP. Arterial calcification after vitamin D. Lancet. 1969;1:416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kingma JG, Jr, Roy PE. Ultrastructural study of hypervitaminosis D induced arterial calcification in Wistar rats. Artery. 1988;16:51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson KE, Abrolat ML, Malone LL, et al. Active serum vitamin D levels are inversely correlated with coronary calcification. Circulation. 1997;96:1755–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andress DL. Vitamin D in chronic kidney disease: a systemic role for selective vitamin D receptor activation. Kidney Int. 2006;69:33–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drissi H, Pouliot A, Koolloos C, et al. 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 suppresses the bone-related Runx2/Cbfa1 gene promoter. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:323–333. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathew S, Lund RJ, Chaudhary LR, Geurs T, Hruska KA. Vitamin D receptor activators can protect against vascular calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1509–1519. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardus A, Panizo S, Parisi E, Fernandez E, Valdivielso JM. Differential effects of vitamin D analogs on vascular calcification. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:860–866. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noonan W, Koch K, Nakane M, et al. Differential effects of vitamin D receptor activators on aortic calcification and pulse wave velocity in uraemic rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210–2217. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, Hix JK. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139–1143. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00530108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foley RN. Clinical epidemiology of cardiac disease in dialysis patients: left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic heart disease, and cardiac failure. Semin Dial. 2003;16:111–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2003.160271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilz S, Marz W, Wellnitz B, et al. Association of vitamin D deficiency with heart failure and sudden cardiac death in a large cross-sectional study of patients referred for coronary angiography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiang W, Kong J, Chen S, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy in vitamin D receptor knockout mice: role of the systemic and cardiac renin-angiotensin systems. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E125–132. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00224.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bodyak N, Ayus JC, Achinger S, et al. Activated vitamin D attenuates left ventricular abnormalities induced by dietary sodium in Dahl salt-sensitive animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16810–16815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611202104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thadhani R. Targeted ablation of the vitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase gene: getting to the heart of the matter. Kidney Int. 2008;74:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou C, Lu F, Cao K, Xu D, Goltzman D, Miao D. Calcium-independent and 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in 1alpha-hydroxylase knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2008;74:170–179. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker L, Koleganova N, Piecha G, Geldyyev A, Noronha IL, Waldherr R, Ritz E, Gross ML. Effect of Paricalcitol and Calcitriol on cardiovascular disease in uninephrectomized ApoE knockout mice. American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting; November 2–5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, Berthold HK, Stehle P, Koerfer R. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:754–759. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park CW, Oh YS, Shin YS, et al. Intravenous calcitriol regresses myocardial hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brumbaugh PF, Haussler MR. Specific binding of 1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol to nuclear components of chick intestine. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1588–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levin A, Gutierrez O, Andress DL, Wolf M. Deficiencies of 25D, 1,25D and inflammation are associated with albuminuria. American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting; November 2–5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agarwal R, Acharya M, Tian J, et al. Antiproteinuric effect of oral paricalcitol in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2823–2828. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alborzi P, Patel NA, Peterson C, et al. Paricalcitol reduces albuminuria and inflammation in chronic kidney disease: a randomized double-blind pilot trial. Hypertension. 2008;52:249–255. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panichi V, Migliori M, Taccola D, et al. Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 in experimental mesangial proliferative nephritis in rats. Kidney Int. 2001;60:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhlmann A, Haas CS, Gross ML, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 decreases podocyte loss and podocyte hypertrophy in the subtotally nephrectomized rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F526–533. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00316.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makibayashi K, Tatematsu M, Hirata M, et al. A vitamin D analog ameliorates glomerular injury on rat glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1733–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan X, Li Y, Liu Y. Therapeutic role and potential mechanisms of active Vitamin D in renal interstitial fibrosis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. [Accessed June 9, 2008]; http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1929/

- 60.Vanholder R, Van Biesen W. Incidence of infectious morbidity and mortality in dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2002;20:477–480. doi: 10.1159/000063556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bikle DD. Vitamin D and the immune system: role in protection against bacterial infection. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:348–352. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ff64a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mandayam S, Shahinian VB. Are chronic dialysis patients at increased risk for cancer? J Nephrol. 2008;21:166–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beer TM, Myrthue A. Calcitriol in cancer treatment: from the lab to the clinic. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guyton KZ, Kensler TW, Posner GH. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogs as cancer chemopreventive agents. Nutr Rev. 2003;61:227–238. doi: 10.1301/nr.2003.jul.227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asakura H, Aoshima K, Suga Y, et al. Beneficial effect of the active form of vitamin D3 against LPS-induced DIC but not against tissue-factor-induced DIC in rat models. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aihara K, Azuma H, Akaike M, et al. Disruption of nuclear vitamin D receptor gene causes enhanced thrombogenicity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35798–35802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arcidiacono MV, Sato T, Alvarez-Hernandez D, et al. EGFR activation increases parathyroid hyperplasia and calcitriol resistance in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:310–320. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tokumoto M, Alvarez-Hernandez D, Archidiacono MV, Andia JC, Skatopolsky E, Dusso A. Contribution of reduced parathryoid vitamin D receptor (VDR) to the switch from diffuse to nodular growth in secondary hyperparathryoidism. American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting; November 2–5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blair D, Byham-Gray L, Lewis E, McCaffrey S. Prevalence of vitamin D [25(OH)D] deficiency and effects of supplementation with ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) in stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients. J Ren Nutr. 2008;18:375–382. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Budoff M, et al. Hypovitaminosis D in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1144–1151. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05781207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tokmak F, Quack I, Schieren G, et al. High-dose cholecalciferol to correct vitamin D deficiency in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chandra P, Binongo JN, Ziegler TR, et al. Cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) therapy and vitamin D insufficiency in patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled pilot study. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:10–17. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chonchol M, Scragg R. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, insulin resistance, and kidney function in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Kidney Int. 2007;71:134–139. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martins D, Wolf M, Pan D, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the United States: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1159–1165. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hermann M, Ruschitzka F. Vitamin D and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2008;10:49–51. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Boer IH, Ioannou GN, Kestenbaum B, Brunzell JD, Weiss NS. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels and albuminuria in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:69–77. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kautzky-Willer A, Pacini G, Barnas U, et al. Intravenous calcitriol normalizes insulin sensitivity in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 1995;47:200–206. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perez-Castrillon JL, Vega G, Abad L, et al. Effects of Atorvastatin on vitamin D levels in patients with acute ischemic heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:903–905. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mizobuchi M, Morrissey J, Finch JL, et al. Combination therapy with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a vitamin D analog suppresses the progression of renal insufficiency in uremic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1796–1806. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Leon F, Kazim H, Masahide M, Jane F, Slatopolsky E. Combination therapy with paricalcitol and enalapril ameliorated cardiac oxidative injury in uremic rats. American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting; November 2–5; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pei YP, Greenwood CM, Chery AL, Wu GG. Racial differences in survival of patients on dialysis. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1293–1299. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gutierrez O, Isakova T, Andress DL, Levin A, Wolf M. Racial differences in the prevalnce and severity of disordered mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease. American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting; November 2–5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wolf M, Betancourt J, Chang Y, et al. Impact of activated vitamin D and race on survival among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1379–1388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wolf M. Active vitamin D and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1442–1443. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]