Abstract

The use of adaptive optics (AO) in a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (AOSLO) allows for long-term imaging of parafoveal capillary leukocyte movement and measurement of leukocyte velocity without contrast dyes. We applied the AOSLO to investigate the possible role of the cardiac cycle on capillary leukocyte velocity by directly measuring capillary leukocyte pulsatility. The parafoveal regions of 8 eight normal healthy subjects with clear ocular media were imaged with an AOSLO. All subjects were dilated and cyclopleged. The AOSLO field of view was either 1.4 × 1.5 degrees or 2.35 × 2.5 degrees, the imaging wavelength was 532 nm and the frame rate was 30 fps. A photoplethysmograph was used to record the subject’s pulse synchronously with each AOSLO video. Parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocities and pulsatility were determined for two or three capillaries per subject. Leukocyte velocity and pulsatility were determined for all eight subjects. The mean parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocity for all subjects was Vmean = 1.30 mm/sec (SD = +/− 0.40 mm/sec). There was a statistically significant difference between leukocyte velocities, Vmax and Vmin, over the pulse cycle for each subject (p<0.05). The mean pulsatility was Pmean= 0.45 (+/− 0.09). Parafoveal capillary leukocyte pulsatility can be directly and non-invasively measured without the use of contrast dyes using an AOSLO. A substantial amount of the variation found in leukocyte velocity is due to the pulsatility that is induced by the cardiac cycle. By controlling for the variation in leukocyte velocity caused by the cardiac cycle, we can better detect other changes in retinal leukocyte velocity induced by disease or pharmaceutical agents.

Keywords: adaptive optics, scanning laser ophthalmoscope, blood flow, pulsatility

Introduction

Evidence suggests that leukocyte adhesion and leukostasis play an important role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy (Lutty et al., 1997; Barouch et al., 2000; McLeod et al., 1995; Schroder et al., 1991). Leukostasis results not only in capillary nonperfusion, but also leads to endothelial damage and corresponding abnormal autoregulation of blood flow, as well as breakdown of the blood retinal barrier, leading to macular edema in diabetes (Antcliff & Marshall, 1999) and other diseases (Miyamoto et al., 1996; Hatchell et al., 1994). Although confocal microscopes have been used to visualize rolling and sticking leukocytes in the conjuctiva (Kirveskari et al., 2001), no objective, non-invasive method to measure long-term hemodynamics in human retina have been demonstrated.

The purpose of this study was to develop and demonstrate effective non-invasive ways to determine the effect of the cardiac cycle on parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocity. Better control for changes in blood flow due to pulse would improve the ability to study alterations in leukocyte transport caused by disease and also to evaluate the benefits of pharmaceutical agents used to treat these diseases.

The scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) has established itself as a useful imaging modality for measuring real-time hemodynamics in human retina. However, all reported direct visualizations of blood flow have employed fluorescent contrast agents to improve signal to noise in the images. Real-time SLO imaging combined with traditional fluorescein injections have been used to visualize and quantify blood flow in human retina (Ohnishi et al., 1994; Wolf et al., 1991; Yang et al., 1997). Another method employed fluorescein-labeled autologous leukocytes that were reinjected into the blood stream (Paques et al., 2000) and visualized with an SLO. Although the fluorescence-based measures are accurate, they are invasive, and the time span for visualization of the leukocytes is limited.

Contrast agents have typically been required to visualize human retinal hemodynamics in the SLO because of limited signal-to-noise in the retinal images, making the smallest features difficult to see. Signal to noise is reduced for two reasons. First, the retinal vasculature is embedded in the retina’s thick, multilayered structure. As such, contrast of the images is reduced because light returning from the retina is comprised of scattered light from multiple structures, not just the vasculature. Second, ocular aberrations of the cornea and lens limit the sharpness (hence contrast) of the retinal images that are recorded.

Adaptive optics (AO) is a technique used in ophthalmoscopy to obtain microscopic access to the living human retina (Liang et al., 1997). By integrating AO into the SLO imaging modality, video-rate ophthalmoscopy on a microscopic scale is possible in living human eyes (Roorda et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006). Correcting the aberrations with the AOSLO helps to overcome signal-to-noise limits of retinal images in two ways. First, the AO-corrected image is sharper because of its improved resolution and higher contrast. Second, the AO-corrected confocal optical section becomes narrower and the detected light is limited to the plane containing the vessels of interest (Romero-Borja et al., 2005). If the subject has normal and otherwise clear optical media, AO makes it possible to image the retina near the diffraction-limit (Zhang & Roorda, 2006). Although the AOSLO system is conducive to fluorescence imaging (Gray et al., 2008) and has shown superb dynamic recordings of flow in the terminal ring of capillaries around the fovea of monkeys (Gray et al., 2006), it also facilitates direct visualization of parafoveal capillary leukocyte dynamics without fluorescent contrast agents (Martin & Roorda, 2005). Obviating the need for extrinsic contrast agents makes long term and repeated measures of capillary blood flow possible with AOSLO, and that may be advantageous for tracking response to therapies, for example.

Prior measurements with AOSLO demonstrated that parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocity is variable in normal subjects and we posited that the variability is likely due to pulsatile changes in velocity (Martin & Roorda, 2005). Observations of pulsatile blood flow in the retina are not new and many techniques have been used to observe or quantify pulsatility. Objective methods include the use of scanning laser Doppler flowmetry and velocimetry (Sullivan et al., 1999; Grunwald et al., 1986; Riva et al., 1992), color Doppler OCT (Yazdanfar et al., 2003), spectral domain Doppler OCT (Wehbe et al., 2007), and direct imaging for brief periods (Nelson et al., 2006). These techniques, however, have to date been unable to record pulsatility in the smallest retinal microvessels and have instead focused on small arteries and veins or optic nerve vasculature. The only demonstrated method that estimates microvascular pulsatility in the parafoveal region employs the blue field entoptic phenomenon (Riva & Petrig, 1980), which is a subjective technique. In the blue-field entoptic phenomenon method, the subject matches the velocity and pulsatility that they observe entoptically with a simulated flow pattern on a computer screen. It should be mentioned that measurements of pulsatility using SLO with fluorescent contrast agents should, in principle, be possible, but none have been reported to date.

Methods

This research followed the tenets of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects after we explained the nature and possible complications of the study. This experiment was approved by the Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Houston and the University of California, Berkeley.

Subjects

Eight normal healthy subjects with clear ocular media were imaged. Subject ages ranged from 21–38 years. All subjects were healthy and had no systemic or ocular disorders. All subjects were dilated prior to imaging with one to two sets of tropicamide 1% and phenylephrine HCl 2.5%. The same clinician assessed resting blood pressure for all subjects prior to dilation to rule out subjects with systemic hypertension. All subjects were imaged in the left eye only using the AOSLO. Imaging sessions for multiple videos lasted approximately 30 minutes excluding subject dilation time. Only one of the subjects reported here was part of the Martin and Roorda 2005 study (subject H was reported as subject D in Martin and Roorda 2005).

AOSLO Imaging System

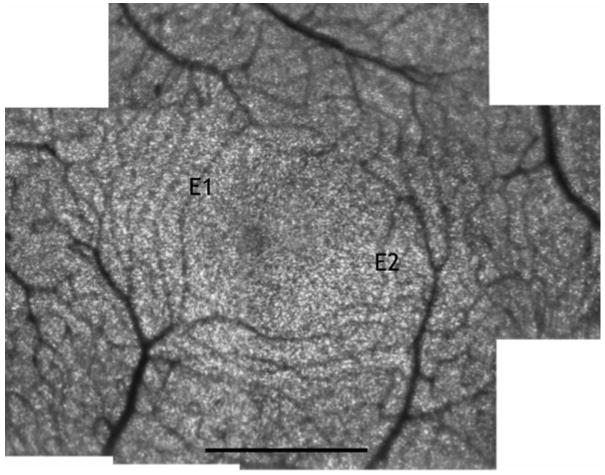

Before the adaptive optics correction was made, the subject’s refractive error was corrected to the nearest 0.25 diopter with spherical and cylindrical trial lenses placed at the subject’s spectacle plane. Then, the AOSLO system employed a Shack Hartmann wavefront sensor (Liang & Williams, 1997) and a 37-channel deformable (Xinetics Inc, Andover MD) mirror to measure and correct the subject’s residual ocular monochromatic aberrations in a closed-loop feedback system. The AOSLO imaging system used in this study is described in greater detail elsewhere (Roorda et al., 2002) A bite bar was used for each subject to aid in stabilization. An imaging wavelength of 532 nm and a frame rate of 30 Hz were used. The AOSLO field of view was either 1.4 × 1.5 degrees or 2.35 × 2.5 degrees sampled into 480 × 512 pixel frames. To properly convert from angle to distance, the axial length of each subject was measured, based on three repeated measurements with either a Sonomed A5500 A-Scan Ultrasound (Latham and Phillips Ophthalmic Products, Inc., Grove City, OH), Carl Zeiss IOL Master (Carl Zeiss Meditech, Inc., Dublin, CA), or Mentor Ophthasonic A-scan/pachometer III (Mentor Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA). Conversion from retinal field angle to true retinal size was performed based on the subject’s axial length as described by Bennett (Bennett et al., 1994). Images were recorded using a maximum of 20 microwatts of 532 nm light (measured at the cornea) which continuously scanned in a raster on the retina. With this exposure level, we were about 20 times lower than the maximum permissible exposure suggested by ANSI (2000). Figure 1 demonstrates the high-resolution images of the parafoveal capillaries and foveal avascular zone that can be obtained with the AOSLO system. The two capillaries that were selected for leukocyte pulsatility are shown for subject E.

Figure 1.

Foveal montage of subject E. The image is comprised of a series of registered images from AOSLO videos. The two capillaries used for leukocyte velocity and pulsatility calculations are marked E1 and E2. The original data was sampled at 205 pixels per degree (1.43 micrometers per pixel for this subject) Scale bar = 500μm.

Leukocyte Velocity as a Function of Cardiac Cycle

A photoplethysmograph (MED Associates Inc., St. Albans, Vermont) was used to record a blood volume waveform synchronously with the AOSLO imaging session. The photoplethysmograph was attached to the subject’s earlobe. The output from the photoplethysmograph signal was digitized and logged into a data file. Additionally, each peak in the subject’s blood volume was identified from the volume trace and encoded onto the corresponding AOSLO video frame as a white bar at the bottom of the frame. (Video 1) The leukocyte position was measured manually for each frame (Martin & Roorda, 2005), employing custom software written in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The software allowed the analyst to play short sequences (which helped to visualize the motion) and freeze frames to manually select and record the leukocyte location. The measurement of each leukocyte’s velocity was computed over an average of seven frames. The mean frame number in each analyzed sequence relative to the frame numbers containing pulse peaks on either side of it was used to compute the relative timing of each velocity measurement with the pulse cycle. The measurements were divided into five equal bins, each corresponding to the segment of the cardiac cycle in which they were observed (Fig. 2). The average leukocyte velocity and SEM for each of these segments of the cardiac cycle were determined. Pulsatility was calculated as the fraction of the change in velocity of the leukocytes over the mean leukocyte velocity, or

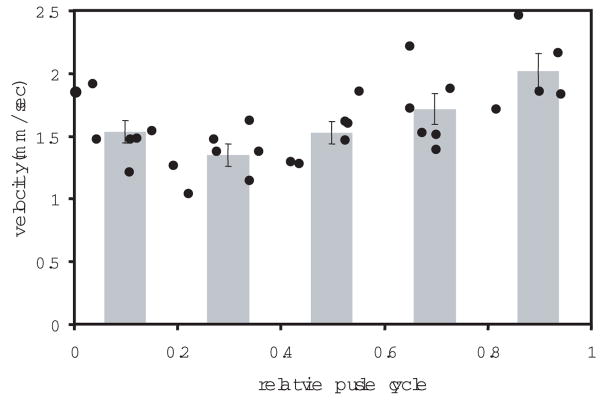

Figure 2.

Mean leukocyte velocity vs. relative cardiac cycle for subject B, observation 1. The points represent the velocities of 31 different leukocytes observed in a single capillary in a single video. A noticeable cyclic trend in the raw leukocyte velocity is shown. The five bars are the bins with average and SEM error bars. Max and min bin values were used to compute the pulsatility.

| (1) |

where Vmax and Vmin are the maximum and minimum of the mean leukocyte velocities calculated from the five equal segments of the cardiac cycle and Vmean is the mean of all leukocyte velocities. We studied leukocyte pulsatility in two to three individual capillaries per subject. In three of the subjects, we repeated a measurement from the same capillary but recorded in a different video that was taken during the imaging session. We assessed leukocyte velocities from the terminal capillary ring to capillaries 3.5° away from the center of the fovea.

Results

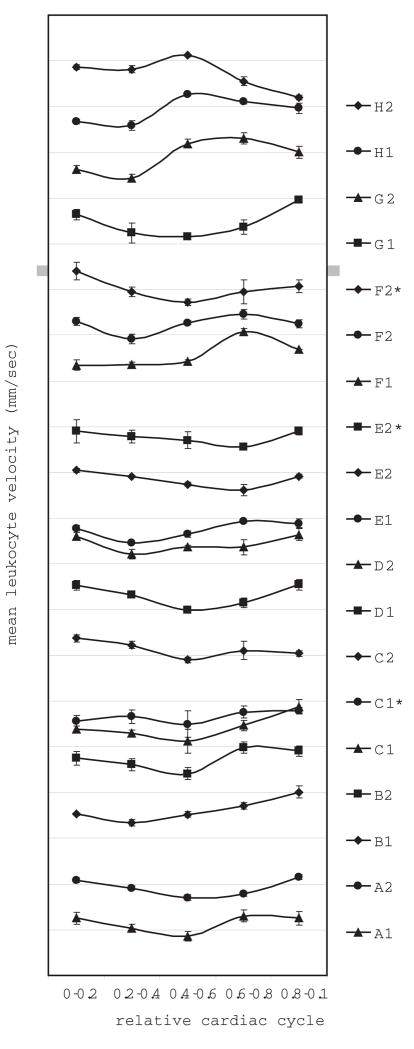

Eighteen to thirty-eight leukocyte velocity measurements were made for each of the 19 capillaries, with 2–3 capillaries per subject, for a total of 533 measurements. Individual leukocyte velocities measured from all subjects ranged from 0.34 – 3.28 mm/sec, mean values ranged from 0.93 – 1.94 mm/sec, and the overall mean was 1.30 mm/sec. The difference between the highest and lowest average leukocyte velocities found for the five bins, Vmax and Vmin respectively, was statistically significant for 15 out of 16 capillaries (ANOVA with contrast, p<0.05) (Minitab Inc. State College, PA) (Fig 3). When four instead of five bins were used, all capillaries were found to have a statistically significant difference between Vmax and Vmin. The pulsatility ranged from 0.31–0.65 (Table 1). The mean pulsatility for all subjects was 0.45.

Figure 3.

Mean leukocyte velocity plotted against relative cardiac cycle for all 8 subjects. The relative cardiac cycle has been divided into five equal bins. The characteristics of the photoplethysmograph traces varied between individuals and also between videos for the same subject, so the phase between the pulse and the velocity measurements are not consistent between the individuals. Error bars represent SEM. * Denotes capillaries in which pulsatility of the same capillary was determined twice in the same imaging session. Divisions on the y-axis are separated by 1 mm/sec and each trace is offset by one division.

Table 1.

Summary of pulsatility data for eight subjects. The change from Vmax is calculated as (Vmax−Vmin)/Vmax × 100%. Vmax and Vmin values are the maximum and minimum bin averages.

| subject | Vmin mm/sec | Vmax mm/sec | Vmean mm/sec | pulsatility | change from Vmax % | HBR beats/min | Blood Pressure mm Hg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.86 | 1.30 | 1.16 | 0.38 | 34 | 64 | 100/65 |

| A2 | 0.70 | 1.16 | 0.92 | 0.49 | 39 | 65 | 100/65 |

| B1 | 1.34 | 2.01 | 1.60 | 0.42 | 33 | 70 | 125/81 |

| B2 | 1.41 | 1.99 | 1.74 | 0.33 | 29 | 70 | 125/81 |

| C1 | 1.13 | 1.88 | 1.35 | 0.56 | 40 | 81 | 118/80 |

| C1* | 0.49 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 36 | 79 | 118/80 |

| C2 | 0.90 | 1.37 | 1.16 | 0.41 | 34 | 80 | 118/80 |

| D1 | 0.99 | 1.54 | 1.29 | 0.43 | 35 | 56 | 128/73 |

| D2 | 1.21 | 1.64 | 1.39 | 0.31 | 26 | 54 | 128/73 |

| E1 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 50 | 50 | 115/62 |

| E2 | 0.61 | 1.04 | 0.85 | 0.51 | 41 | 49 | 115/62 |

| E2* | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 37 | 50 | 115/62 |

| F1 | 1.31 | 1.93 | 1.51 | 0.41 | 32 | 70 | 130/70 |

| F2 | 0.92 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 36 | 73 | 130/70 |

| F2* | 0.72 | 1.40 | 1.03 | 0.65 | 48 | 68 | 130/70 |

| G1 | 1.24 | 1.97 | 1.54 | 0.47 | 37 | 61 | 115/70 |

| G2 | 1.44 | 2.31 | 1.94 | 0.45 | 37 | 61 | 115/70 |

| H1 | 1.58 | 2.27 | 1.93 | 0.36 | 30 | 67 | NA |

| H2 | 1.20 | 2.12 | 1.82 | 0.50 | 43 | 66 | NA |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 1.00 | 1.58 | 1.30 | 0.45 | 37 | 65 | |

| SD | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 6 | 9.97 | |

Denotes capillaries in which pulsatility of the same capillary was determined twice in the same imaging session.

The only factor we measured that was significantly correlated (linear regression, p<0.05) with pulsatility was Vmin, which had a negative correlation (ie the lower the Vmin the higher the pulsatility). Pulsatility showed no correlation with blood pressure (systolic, diastolic and systolic – diastolic), Vmean or Vmax.

The repeated capillary measurements are denoted with * in Table 1. Subject E and F had somewhat repeatable levels of pulsatility. However there was a large amount of variation in the mean, minimum, and maximum leukocyte velocities in these capillaries. Subjects C and E had significantly different velocities between repeated sessions (two-tailed t-Test, P<0.05).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the AOSLO can be used to measure leukocyte pulsatility in parafoveal capillaries, including the smallest capillaries that line the foveal avascular zone. The overall mean leukocyte pulsatility for all subjects of 0.45 is lower than a previous study of 0.98, which employed the blue field entoptic phenomenon (Riva & Petrig, 1980). Both techniques are thought to measure leukocyte motion and not erythrocytes so that cannot explain the difference (Sinclair et al., 1989; Arend et al., 1995). Our pulsatility values will be lowered by the binning method we adopted to estimate maximum and minimum velocities (see ‘Limitations’ below) but they may also be due to the different measurement methods used - subjective versus objective - or the difference in the overall assessed retinal area which can be much larger for the blue field entoptic phenomenon than the AOSLO. When retinal capillary blood flow volume was assessed with scanning laser Doppler flowmetry it was found that the blood flow did fluctuate in the capillaries located between large vessels as much as 50% and the authors believed that this fluctuation was due mostly to the effect of the cardiac pulse (Sullivan et al., 1999). Their finding of blood flow fluctuations of up to 50% is higher than our average finding of 37%. However, their blood flow measurements were not taken in the parafoveal region, which may confound a true comparison between pulsatility measurements.

Although the velocity was periodic and a significant variation due to pulse was detected, leukocytes did not appear to have the characteristic pulsatile velocity profiles that are observed in larger vessels (Wehbe et al., 2007). Furthermore, they were different between capillaries and between individuals. This is likely due to the physical impact of the small capillary diameter on the flow, especially considering that leukocytes often must deform to pass through the smallest capillaries (Gaehtgens et al., 1984).

Of all the measures, Vmax, Vmin, Vmean, pulsatility and ‘change from Vmax’, the pulsatility and ‘change from Vmax’ had the least intersubject variation. Variation in pulsatility correlated with Vmin, but did not correlate with Vmax, Vmean, heart beat rate, blood pressure, or difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Other sources of inter-subject variability might be due to capillary diameter (which was not measured in this study), dynamic changes in blood pressure, or local regulatory changes in blood flow and perfusion pressure. The AOSLO may prove to be an effective technology for examining these factors in the future.

Advantages

A major advantage of assessing retinal capillary leukocyte pulsatility is that we can now control for the normal amount of leukocyte velocity fluctuations induced by the cardiac cycle. This will allow us to better isolate the effects of diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, or glaucoma on retinal capillary hemodynamics. This work also demonstrates the high level of sensitivity that is obtainable when using the AOSLO imaging system to capture small alterations in retinal leukocyte velocity.

Limitations

Since relatively clear ocular media is currently necessary for the adaptive optics to perform well, this technique could not be used on some subjects with poorer ocular clarity. This might include subjects with severe cataracts or cornea surface and tear film irregularities. Nonetheless, the confocal SLO method is more immune to scatter than most imaging modalities, and we have been able to visualize blood flow in most subjects to date.

In order to determine leukocyte velocity pulsatility a large number of leukocytes must be observed to achieve statistical significance in the difference between Vmax and Vmin. Since there are a relatively small number of leukocytes in blood versus erythrocytes one must usually measure all leukocyte velocities over a 20 second video in order to allow for the most accurate assessment of pulsatility. In some patients, it was difficult to obtain a 20 second video of a high enough resolution to assess pulsatility. The most common problems that occurred while collecting a 20 second video were tear film degradation during the video collection, slightly unstable subject fixation, or an excessive number of blinks. We currently use a bite bar to aid in stabilizing the patient while imaging. Image degradation caused by subject head movements and fixational instability on video collection may be reduced in future work by employing a pupil tracker or image stabilization software/hardware in place of a bite bar. We have tried using various artificial tear solutions with little improvement in image quality. However, artificial tears sometimes aid in patient comfort, which may allow for more accurate fixation and fewer blinks in some subjects.

The binning method used was necessary to confirm that the leukocyte velocity changes were statistically significant. Furthermore, each velocity measure was computed over an average of 7 video frames. The downside of this method is that it will underestimate the maximum and overestimate the minimum velocity values, with the combined effect of generating a lower pulsatility than would be estimated using other methods. It should be noted here that any method that employs averaging, either subjective or objective are subject to the same problem. For one subject, we needed to reduce the number of bins from 5 to 4 in order to obtain a statistically significant measure of pulsatility.

Conclusions

This paper demonstrates a new method for assessing the effects of the cardiac cycle on parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocity. By directly and non-invasively measuring parafoveal capillary leukocyte pulsatility using the AOSLO imaging system one can now control for the fluctuations in retinal capillary velocity induced by the heartbeat when studying the effects of retinal diseases known to affect retinal hemodynamics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH/NEI grants EY13299 and EY014365 to AR, the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Adaptive Optics, managed by the University of California at Santa Cruz under cooperative agreement #AST-9876783, and the American Optometric Foundation William C. Ezell Fellowship to JAM. Thanks to Siddharth Poonja for computer programming and hardware setup related to the photoplethysmograph.

Abbreviations

- AOSLO

Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope

- AO

Adaptive optics

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- ANSI. American National Standard for the Safe Use of Lasers ANSI Z136.1-2000. Orlando, Florida: Laser Institute of America; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Antcliff RJ, Marshall J. The pathogenesis of edema in diabetic maculopathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 1999;14:223–232. doi: 10.3109/08820539909069541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend O, Harris A, Sponsel WE, Remky A, Reim M, Wolf S. Macular capillary particle velocities: a blue field and scanning laser comparison. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233:244–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00183599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch FC, Miyamoto K, Allport JR, Fujita K, Bursell SE, Aiello LP, Luscinskas FW, Adamis AP. Integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion and retinal leukostasis in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1153–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AG, Rudnicka AR, Edgar DF. Improvements on Littmann’s method of determining the size of retinal features by fundus photography. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994;232:361–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00175988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaehtgens P, Pries AR, Nobis U. Flow behaviour of white cells in capillaries. Kroc Found Ser. 1984;16:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DC, Merigan W, Wolfing JI, Gee BP, Porter J, Dubra A, Twietmeyer TH, Ahmad K, Tumbar R, Reinholz F, Williams DR. In vivo fluorescence imaging of primate retinal ganglion cells and retinal pigment epithelium cells. Optics Express. 2006;14:7144–7158. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.007144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DC, Wolfe R, Gee BP, Scoles D, Geng Y, Masella BD, Dubra A, Luque S, Williams DR, Merigan WH. In vivo imaging of the fine structure of rhodamine-labeled macaque retinal ganglion cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:467–473. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald JE, Riva CE, Sinclair SH, Brucker AJ, Petrig BL. Laser Doppler velocimetry study of retinal circulation in diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:991–996. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190049038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchell DL, Wilson CA, Saloupis P. Neutrophils plug capillaries in acute experimental retinal ischemia. Microvasc Res. 1994;47:344–354. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1994.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirveskari J, Vesaluoma MH, Moilanen JA, Tervo TM, Petroll MW, Linnolahti E, Renkonen R. A novel non-invasive, in vivo technique for the quantification of leukocyte rolling and extravasation at sites of inflammation in human patients. Nat Med. 2001;7:376–379. doi: 10.1038/85538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Williams DR. Aberrations and retinal image quality of the normal human eye. J Opt Soc Am A. 1997;14:2873–2883. doi: 10.1364/josaa.14.002873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Williams DR, Miller D. Supernormal vision and high-resolution retinal imaging through adaptive optics. J Opt Soc Am A. 1997;14:2884–2892. doi: 10.1364/josaa.14.002884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutty GA, Cao J, McLeod DS. Relationship of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to capillary dropout in the human diabetic choroid. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:707–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Roorda A. Direct and noninvasive assessment of parafoveal capillary leukocyte velocity. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2219–2224. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DS, Lefer DJ, Merges C, Lutty GA. Enhanced expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin in the diabetic human retina and choroid. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:642–653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K, Ogura Y, Hamada M, Nishiwaki H, Hiroshiba N, Honda Y. In vivo quantification of leukocyte behavior in the retina during endotoxin-induced uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2708–2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Ben-Cnaan R, Rosner M, Belken M, Grinvald A. Reduction of the Variance of Blood-Flow Velocity Measurements by Triggering on the Heartbeat-Cycle Phase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci Supplem. 2006 E-Abstract #2650. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi Y, Fujisawa K, Ishibashi T, Kojima H. Capillary blood flow velocity measurements in cystoid macular edema with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques M, Boval B, Richard S, Tadayoni R, Massin P, Mundler O, Gaudric A, Vicaut E. Evaluation of fluorescein-labeled autologous leukocytes for examination of retinal circulation in humans. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:560–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva CE, Harino S, Petrig BL, Shonat RD. Laser doppler flowmetry in the optic nerve. Exp Eye Res. 1992;55:499–506. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90123-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva CE, Petrig B. Blue field entoptic phenomenon and blood velocity in the retinal capillaries. J Opt Soc Am. 1980;70:1234–1238. doi: 10.1364/josa.70.001234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Borja F, Venkateswaran K, Roorda A, Hebert TJ. Optical slicing of human retinal tissue in vivo with the adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Appl Opt. 2005;44:4032–4040. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.004032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roorda A, Romero-Borja F, Donnelly WJ, Queener H, Hebert TJ, Campbell MCW. Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Optics Express. 2002;10:405–412. doi: 10.1364/oe.10.000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder S, Palinski W, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Activated monocytes and granulocytes, capillary nonperfusion, and neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:81–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair SH, Azar-Cavanagh M, Soper KA, Tuma RF, Mayrovitz HN. Investigation of the source of the blue field entoptic phenomenon. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:668–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P, Cioffi GA, Wang L, Johnson CA, Van Buskirk EM, Sherman KR, Bacon DR. The influence of ocular pulsatility on scanning laser Doppler flowmetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehbe H, Ruggeri M, Jiao S, Gregori G, Puliafito CA, Zhao W. Automatic retinal blood flow calculation using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2007;15:15193–15206. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.015193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Arend O, Toonen H, Bertram B, Jung F, Reim M. Retinal capillary blood flow measurement with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Preliminary results Ophthalmology. 1991;98:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Kim S, Kim J. Fluorescent dots in fluorescein angiography and fluorescent leukocyte angiography using a scanning laser ophthalmoscope in humans. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1670–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdanfar S, Rollins AM, Izatt JA. In vivo imaging of human retinal flow dynamics by color Doppler optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:235–239. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Poonja S, Roorda A. MEMS-based Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscope. Optics Letters. 2006;31:1268–1270. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.001268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Roorda A. Evaluating the lateral resolution of the adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:014002. doi: 10.1117/1.2166434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.