Abstract

There have been relatively few population-based studies that have documented the extent of tobacco use among those with mental health disorders. Recently, the K6 scale, designed to assess serious psychological distress (SPD) at the population level, has been incorporated into a number of population-based health behavior surveys. The present study documented the prevalence of tobacco use products, dependence, and quit behavior among those with and without SPD utilizing the 2002 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Results from the current study indicated that adults with SPD had greater odds of lifetime, past month, and daily use of cigarettes, cigars and pipes than adults without SPD. Common measures of nicotine dependence (e.g., Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale) indicated that a greater percentage of those with SPD were nicotine dependent compared to those without SPD. Lastly, quit ratios differed notably by SPD status. Among those with SPD, 29% quit or were former smokers compared to 49% of those without SPD. Findings highlight the importance of continuing to enhance public health efforts towards smoking cessation among those with mental health disorders, extensive tobacco surveillance and monitoring of tobacco trends among this group, and evaluating the extent to which this group of smokers may contribute to a hardening of the population.

1. Introduction

Despite the continued decline of tobacco use over the past few decades, certain sub-populations continue to have high rates of smoking. Previous clinical research has consistently documented elevated rates of cigarette use among those with specific mental health disorders in comparison to the general population (Hughes, Hatsukami, Mitchell, & Dahlgren, 1986; Prochaska, Gill & Hall, 2004; Vanable, Carey, Carey & Maisto, 2003). Overall, the prevalence rates for current cigarette use among clinical samples have been shown to vary depending upon the type of disorder ranging from approximately 40% to 85% for those with schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder and other serious mental health disorders (Kalman, Baker-Morissette, & George, 2005). In addition, rates of cigarette use have been shown to be more elevated among inpatients (e.g., individuals with more severe psychiatric impairment) relative to outpatient samples (e.g., less severe forms of depression) (Baker-Morissette, Gulliver, Wiegel & Barlow, 2004; Dalack, Healy, Meador-Woodruff, 1998). Also, individuals with the most severe forms of mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenics) are more addicted to tobacco, with heavier smoking and elevated scores on clinical measures of nicotine dependence (Jacobsen, D’Souza, Menel, Pugh, Skudlarski, & Krystal, 2004).

At this time, there is a paucity of research that has examined rates of cigarette use among those with mental health disorders using a nationally representative sample. Lasser and colleagues (2000), using data from the National Comorbidity Study (NCS), documented that persons with specific past month mental health disorders were twice as likely to smoke and consumed nearly half (44.3%) of all cigarettes sold in the U.S. Additionally, quit rates for those smokers with mental health problems ranged from 27–34%, which were lower compared to smokers who did not have any history of a mental health disorder (i.e., 43%). More recently, Grant, Hasin, Chou, Stinson & Dawson (2004), examined results from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) and found that individuals with a current psychiatric disorder made up 30.3% of the population and consumed 46.3% of all cigarettes consumed in the United States.

The ability to assess tobacco use among those with mental health disorders at the population level is complicated by the intended purpose and scope of the specific population-based health survey. At this time, there are no publicly available population surveys that comprehensively assess both mental health disorders and tobacco use. For example, the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) was chiefly designed to document the prevalence of specific mental health disorders, while the specific tobacco use indicators within this survey are limited to examining only cigarette consumption (Lasser et al., 2000). Alternatively, other population based health surveys, such as the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) provide more extensive coverage of tobacco use, including other tobacco products, nicotine dependence indicators, and the economic and financial implications of smoking, but they do not incorporate extensive assessment of specific psychological disorders.

Recently, there has been an increased effort to incorporate brief psychological screening tools in population-based surveys in order to measure an individual’s current mental health status. The K6 scale, a brief psychological screening instrument, was developed by Kessler and colleagues (2002) to screen at the population level for individuals with possible severe mental illness. Specifically, the K6 scale consists of six questions, which ask respondents to report how frequently they experience symptoms of serious psychological distress (SPD) within a particular reference period. Although the K6 focuses on non-specific psychological distress, the scale has been clinically validated. Because of its high specificity, the majority of cases detected by the K6 would meet DSM-IV criteria for certain mental health disorders (Kessler et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 2003). In sum, its brevity, strong item response characteristics, and ability to discriminate DSM-IV cases from non-cases makes the K6 ideal for general population-based health surveys.

The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) has included the K6 scale for some years now, but we found no peer-reviewed literature examining the relationship between tobacco use and SPD using this survey. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to document the prevalence of tobacco use products, dependence, and quit behavior among those with and without SPD utilizing the 2002 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.

2. Methods

2.1 Survey description

Data for the current study was derived from the 2002 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which provides national alcohol and drug use estimates for the U.S. civilian population annually. The NSDUH is a 50-State design, with independent stratified, multistage, area probability samples selected from each State to yield nationally representative findings. Subject interviews were conducted anonymously in-person by responding to questions via a computer-assisted interview module. In 2002, the NSDUH provided a weighted screening response rate of 91% and a weighted interview response rate of 79%. A detailed description of the survey design and sampling procedures are provided elsewhere (SAMHSA, 2002).

The 2002 NSDUH public access dataset contains a sample of 54,079 individual records for those aged 12 and older. However, the K6 scale was administered only to adults who were 18 and older. For the purpose of this study, our analyses focused on adults, ages 18 and older, who provided data on the K6 scale, which resulted in 36,370 individual records.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographic information

Participant demographic data were collected via self-report by responding to a series of questions. Specifically, questions pertaining to gender, race/ethnicity, employment status, overall health status, educational level, age, marital status, family income, alcohol/drug abuse or dependence, and whether individuals lived in a densely populated area were obtained.

2.2.2 Serious psychological distress (SPD)

Serious psychological distress was measured via the K6 scale. The K6 scale was developed by Kessler and colleagues (2002, 2003) as a screening tool to measure symptoms of psychological distress in the general population. The K6 consists of six questions, which ask respondents how frequently they experienced symptoms of serious psychological distress (i.e., felt nervous, restless, hopeless, worthless, sad, and felt that everything was an effort) during their worst month emotionally in the past year. The six items are coded from 0 to 4 and summed to yield a number between 0 and 24. Participants with scores ≥ 13 were classified as having SPD (Kessler et al., 2002, 2003).

2.2.3 Tobacco Use Measures

Lifetime use of cigarettes, commonly referred to as ever smokers, was defined as having smoked 100 or more cigarettes in one’s lifetime. Current cigarette use was defined as having smoked 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and at least one day within the past month. Daily cigarette smoking was defined as having smoked 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and smoking cigarettes on all 30 of the past 30 days. Former smokers were defined as individuals that have smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, but reported not smoking in the past 30 days. The quit ratio was calculated as the ratio of former to ever smokers and is considered a measure of total cessation in a population. The NSDUH also asks participants about their use of other tobacco products including cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco. For the current study, we present ever and past month use rates for each of these tobacco products.

2.2.4 Nicotine Dependence Measures

The NSDUH includes two separate instruments independently designed to assess the extent and severity of nicotine dependence. The Nicotine Dependence Severity Scale (NDSS) was originally developed by Shiffman & Sayette (2004), and represents a multidimensional measurement of nicotine dependence. It consists of a total dependence score (total sum of 17 items) or five sub-scale scores (Drive, Priority, Tolerance, Continuity, Sterotypy). For the current study, participants were asked to rate the 17 items (e.g., tend to avoid places that do not allow smoking) on 5 point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely true) and a total dependence score was derived by summing these items together. Current cigarette smokers were classified as nicotine dependent if their NDSS score was ≥ 2.75. Research on the NDSS has documented good to excellent psychometric properties (e.g., internal consistency) associated with the instrument across a number of diverse samples (Shiffman & Sayette, 2005).

The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) is a common measure of nicotine dependence. For the NSDUH, one item in the FTND was chosen for its ability to discriminate dependent smokers, which specifically asks respondents how soon after waking smokers have their first cigarette (SAMSHA, 2002). In this sample, a current cigarette smoker was defined as nicotine dependent, based on the single FTND item, if the first cigarette smoked was within 30 minutes of waking up on the days that he or she smoked. Extensive work has been done to establish the psychometric properties of the FTND, which has shown it to be both a valid and reliable measure of nicotine dependence across a number of diverse populations (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

2.3 Data analytic plan

For all analyses, sample weights were applied to the data to adjust for non-response and the varying probabilities of selection, including those resulting from over-sampling, yielding nationally representative findings. All analyses were conducted with SUDAAN statistical software, which corrects for the complex sample design, and was used to generate 95% confidence intervals (Research Triangle Institute [RTI], 2004). Bivariate analyses were used to produce point estimates for types of tobacco products used, quit rates, and measures of dependency in smokers by SPD status, and 95% confidence variables were generated for the various point estimates. Differences between estimates were considered statistically significant at the p < .05 level if the 95% confidence intervals did not overlap. Odds ratios were computed based on the bivariate analyses to examine the likelihood of smoking and its related correlates among those with SPD using logistic regression analytic techniques. Additionally, to determine the unique impact of SPD status on the various types of tobacco products, adjusted multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted with the following variables adjusted for in the models: age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational level, alcohol/drug abuse or dependence.

Results

3.1 Demographic differences by SPD status

Overall, 8.3% of adults in the U.S. were found to have serious psychological distress (SPD) in the past year. As shown in Table 1, individuals with and without SPD differed significantly on a number of demographic variables (all p’s ≤ .0001). Most notably, adults with SPD were more likely to be female (66% vs. 50.7%) and between the ages of 18–25 (22.9% vs. 14%) compared to those without SPD. In addition, SPD respondents were more likely to be employed part-time, live in a densely populated area, not currently married, less educated, have lower incomes, and report less than “excellent” health. Further, adults with SPD were less likely to be covered by health insurance and married and more likely to report alcohol or drug abuse or dependency in the past year compared to those without SPD.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics by SPD status, NSDUH 2002

| Past year SPD (n = 4008) |

No SPD (n = 32362) |

p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0001 | ||

| Male | 34 | 49.3 | |

| Female | 66 | 50.7 | |

| Age | 0.0001 | ||

| 18–25 Years Old | 22.9 | 14 | |

| 26–34 Years Old | 20.8 | 16.3 | |

| 35–49 Years Old | 33.4 | 30.9 | |

| 50 or Older | 22.9 | 38.8 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0001 | ||

| White | 72.5 | 71.1 | |

| Black/African American | 11.7 | 11 | |

| Hispanic | 9.9 | 12.1 | |

| Other | 5.9 | 5.7 | |

| Employment Status | 0.0001 | ||

| Employed Full-Time | 48.4 | 55.9 | |

| Employed Part-Time | 14.7 | 12.9 | |

| Unemployed | 6.5 | 3.4 | |

| Other | 30.3 | 27.8 | |

| Marital Status | 0.0001 | ||

| Married | 38.3 | 58.2 | |

| Widowed | 5.1 | 6.5 | |

| Divorced or Separated | 21.1 | 12.8 | |

| Never Been Married | 35.5 | 22.4 | |

| Education | 0.0001 | ||

| Less than HS | 54.3 | 49.6 | |

| HS diploma or GED | 45.7 | 51.4 | |

| Total Family Income | 0.0001 | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 31.1 | 18.6 | |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 38.9 | 38.5 | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 15 | 18.3 | |

| $75,000 or more | 15 | 24.7 | |

| Covered by any Health Insurance | 80.4 | 87.4 | 0.0001 |

| Perceived Overall Health | 0.0001 | ||

| Excellent | 15.1 | 25.7 | |

| Very Good | 29.2 | 37.3 | |

| Good | 30 | 25.9 | |

| Fair | 25.7 | 11.1 | |

| Population Density | 0.0001 | ||

| Lives in MSA with more than one million people | 41 | 45.1 | |

| Lives in MSA with less than one million people | 34.5 | 33.1 | |

| Does not live in a MSA | 24.5 | 21.9 | |

| Alcohol or Drug Abuse or Dependence in past year | 23.3 | 8.2 | 0.0001 |

3.2 Tobacco use by SPD status

Table 2 summarizes the prevalence, crude odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (AOR), and 95% C.I.(s) associated with these estimates for ever and past month use by each type of tobacco product between those with and without SPD. The prevalence rates among adults with SPD for ever use of any tobacco, cigarettes, and cigars were higher than for adults without SPD. Adults with SPD also had higher rates than adults without SPD for past month cigarette use (44.9% vs. 26%) and daily cigarette use (30.2% vs. 16.7%).. Rates for past month use of any tobacco, cigars, and pipes were also greater for adults with SPD compared to those without SPD. Alternatively, the rates for ever and past month use of smokeless tobacco and ever use of pipes were slightly lower for adults with SPD compared to adults without SPD.

Table 2.

Percentages and odds ratios for type of tobacco product by SPD status

| SPD status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (SPD score ≥ 13) | No (SPD score ≤ 12.99) | |||||

| Weighted % | Weighted % | UOR | 95% CIs | AOR* | 95% CIs | |

| Ever Used | ||||||

| Any Tobacco | 84.8 | 76.7 | 1.70** | 1.45–2.00 | 1.69** | 1.44–1.99 |

| Cigarettes | 82.6 | 72.5 | 1.79** | 1.54–2.08 | 1.72** | 1.48–2.01 |

| Cigars | 41.3 | 39.8 | 1.06 | .95–1.19 | 1.24** | 1.08–1.42 |

| Smokeless Tobacco | 20.7 | 21.2 | .97 | .85–1.10 | 1.07 | .92–1.25 |

| Pipes | 15.0 | 18.9 | .76 | .65–.89 | 1.32** | 1.09–1.61 |

| Past Month Use | ||||||

| Any Tobacco | 48.0 | 30.8 | 2.08** | 1.86–2.33 | 1.74** | 1.54–1.97 |

| Cigarettes | 44.9 | 26.0 | 2.33** | 2.08–2.60 | 1.82** | 1.61–2.06 |

| Cigars | 7.1 | 5.3 | 1.36** | 1.14–1.63 | 1.25** | 1.03–1.51 |

| Smokeless Tobacco | 2.7 | 3.5 | .76** | .58–.99 | .76 | .571.02 |

| Pipes | 1.3 | .8 | 1.71** | 1.03–2.85 | 2.1** | 1.25–3.53 |

| Daily cigarette smoking | 30.2 | 16.7 | 2.15** | 1.90–2.43 | 1.82** | 1.59–2.07 |

| Lifetime cigarette smoker | 71.3 | 65.9 | 1.28** | 1.13–1.46 | 1.38** | 1.21–1.59 |

Source: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies, National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2002

UOR = Unadjusted odds ratio; AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Smokeless tobacco products consists of both chewing tobacco and snuff use

The following variables are controlled for in the logistic regression analyses: age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational level, alcohol/drug abuse or dependence

Denotes significance at p < .05

Analyses of the crude OR(s) indicated that SPD was a significant contributor to ever and past month use of certain tobacco products. Adults with SPD were significantly more likely than adults without SPD to report ever use of any tobacco and cigarettes, past month use of any tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes as well as lifetime and daily use of cigarettes. However, adults with SPD were less likely to report past month use of smokeless tobacco products (i.e., chew and snuff) compared to adults without SPD.

To examine the unique contribution of SPD status with respect to ever and past month use of each of the types of tobacco products, multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted adjusting for the following variables: age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational level, and alcohol/drug abuse or dependence. Similar to the crude OR(s), the AOR(s) for adults with SPD indicated that they were more likely to be ever users of any tobacco and cigarettes as well as past month users of any tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes compared to those without SPD. In addition, both the crude OR(s) and AOR(s) did not appear to change substantially for these estimates. Alternatively, the AOR(s) for ever use of cigars and pipes increased in comparison to their crude OR(s), and indicated that adults with SPD were more likely to consume these products in their lifetime than those without SPD. Further, the AOR for past month use of smokeless tobacco did not remain statistically significant after adjustment.

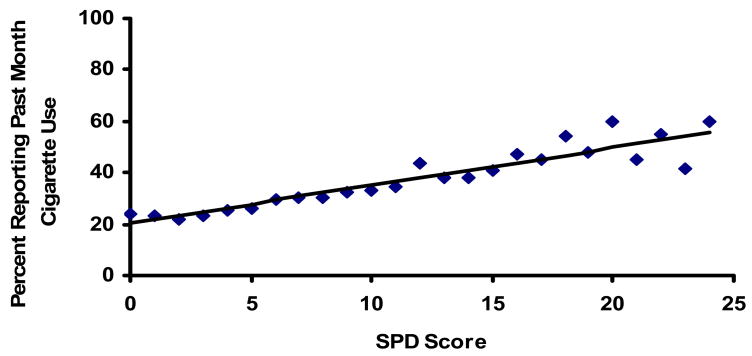

3.2 Prevalence of past month cigarette use by SPD severity

Figure 1 displays the relationship between the overall prevalence of past month cigarette use by the prevalence of SPD severity. The scatter-plot indicated that as the overall prevalence of past month cigarette use increased the prevalence of SPD severity increased, although there is considerable variability. More specifically, at the defined cutoff (i.e., scores ≥ 13) for the K6 scale, the data points scattered above and below the displayed line compared to those below the defined cutoff, which appeared to have less scatter around the line.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of the relationship between the prevalence of past month cigarette use and prevalence of SPD severity

3.3 Nicotine Dependence by SPD status

As shown in Table 3, among past month cigarette smokers with SPD, a substantial percentage of these respondents were nicotine dependent. According to the NDSS, a greater percentage of those with SPD were more likely to be nicotine dependent compared to those without SPD. With respect to time to first cigarette, a significant proportion of SPD respondents indicated smoking within the first 30 minutes from waking (i.e., single FTND item) and greater smoking urgency (i.e., smoking within five minutes from waking) compared to their counterparts.

Table 3.

Nicotine dependence and SPD status based on past month tobacco use according to the NDSS and the FTND, NSDUH 2002

| SPD status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (SPD score ≥ 13) | No (SPD score ≤ 12.99) | |||

| Weighted % | 95 % CI | Weighted % | 95 % CI | |

| Nicotine Dependence based on NDSS score | 49.7 | ± 3.67 | 33.3 | ± 1.39 |

| Time to first cigarette | ||||

| Smoked first cigarette within five minutes from waking | 29.2 | ± 3.61 | 19.3 | ± 1.29 |

| *Smoked first cigarette within 30 minutes from waking | 57.6 | ± 3.53 | 42.1 | ± 1.47 |

Note:

Derived from a single item of the FTND

Source: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies, National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2002

Percentages are based on weighted population estimates

3.4 Quit rates by SPD status

In the NSDUH 2002, the overall quit ratio for adults in the U.S. population was .47. In other words, 47% of ever smokers in the U.S. have quit or were former smokers at the time of the survey. Further analyses indicated that the quit ratio differed notably by SPD status. The quit ratio for adults without SPD was .49 (i.e., 49% have quit or were former smokers) whereas the quit ratio for those with SPD was .29 (i.e., 29% have quit or were former smokers) indicating that those with SPD are less likely to quit smoking.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that SPD was a significant contributor to ever and past month tobacco use. As expected, individuals with SPD were significantly more likely to be ever cigarette smokers, smoked cigarettes within the past month, and smoke cigarettes daily. Similarly, they are more likely to ever smoke any tobacco, cigars and pipes, and consume any tobacco, cigars, and pipes within the past month. A greater percentage of those with SPD were tobacco dependent and were more likely to have greater smoking urgency (i.e. smoke immediately upon wakening or within the first 30 minutes from waking) compared to those without SPD. Further, adults with SPD are much less likely to quit smoking, and appear to smoke more as the severity of their symptoms increase. Study findings are consistent with previous research, which have reliably documented elevated smoking rates of cigarette use and quit rates as well as greater levels of nicotine dependence among those with specific mental health disorders among both small clinical and population-based samples (Grant et al., 2004; Lasser et al., 2000; Prochaska et al., 2004; Vanable et al., 2003).

The present study extended existing research by examining the prevalence of other tobacco products (i.e., smokeless tobacco, pipes, and cigars) among those with mental health impairments in a nationally representative sample. Our findings indicate that those with SPD were significantly more likely to report ever and past month use of pipes and cigars compared to their counterparts when controlling for a number of demographic factors. Recently, epidemiological evidence has indicated that cigarette consumption among the general population has been decreasing, while the use of other tobacco products (e.g., cigars) has begun to increase (Delnevo, 2006; Giovino, 2002). The information provided from this study suggests that the use of other tobacco products among those with mental health impairments should not be ignored and continued to be monitored, as it may be part of an emerging trend. Further, our knowledge about what factors contribute to the use of these products among those with SPD or specific mental health disorders remains unknown. Identification of specific mediating and moderating factors that contribute to the use of these tobacco products among those with SPD is warranted.

Most studies that have examined rates of smoking among those with mental health disorders have incorporated extensive clinical assessment of specific disorders. In the current study, the K6 scale was used as a proxy for mental health status, and appears to be able to reliably discriminate between rates of tobacco use by SPD status, despite lacking specific diagnostic information. We found tobacco use estimates that were similar to those found in prior research of serious mental illnesses (Grant et al., 2004; Lasser et al., 2000; Prochaska et al., 2004). The finding that the severity of SPD appeared to be linearly related to prevalence of past month cigarette use again validated prior clinical research linking smoking to mental illness severity (Baker et al., 2004; Kalman et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005). The relationship between poor mental health and smoking is consistent across studies regardless of the type of mental health measure utilized. Therefore, our findings highlight the importance of the K6 scale for its ability to distinguish between rates of tobacco use by SPD status and recommend that this scale continue to be used as a proxy indicator for mental health, as well as incorporated into other health behavior surveys, due to its low cost and ease of use in population-based health surveys.

The quit rate among those with SPD was notably lower than those without SPD indicating that those with SPD were less likely to quit smoking. A recent debate in the tobacco control literature is the notion of “hardening” (NCI, 2003; Warner & Burns, 2003). This concept implies that certain sub-populations, particularly those with mental health co-morbidities, may have greater difficulty achieving abstinence because of lack of resources or other factors that impede their ability to quit. The reduction in the overall cigarette smoking prevalence in the U.S. has been decreasing minimally in recent years (Giovino, 2002;United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2000), which suggests that certain sub-populations (e.g., individuals with mental health disorders) may have hardened. A more formal evaluation of hardening is necessary to examine rates of smoking among those with SPD or other mental health disorders at the population level across a specific period (e.g., last 10 years) to determine if this group comprises a disproportionate number of smokers across time. Examining the extent to which those with mental health impairments have hardened or remained resistant to smoking may provide tobacco control researchers with valuable information regarding the relative impact of specific tobacco control policies on this group of smokers.

Another interesting result concerns the prevalence of nicotine dependence among persons with SPD. According to the NDSS, approximately half of the respondents who reported both SPD and past month cigarette use did not meet nicotine dependence criteria. These smokers, therefore, may be less likely to receive clinical attention for their tobacco use behavior. Smoking cigarettes poses no less physical harm to those who do not meet diagnostic criteria for nicotine dependence and thus, this group of smokers must not go unnoticed. It remains necessary for public health and treatment efforts to focus on those with mental health impairments regardless of whether or not they are nicotine dependent.

There were some limitations associated with the current study. The data were collected via self-report, which may raise concerns regarding the veracity of the data. In contrast, however, recent research has indicated that incorporating certain methodological procedures (e.g., assurances of confidentiality, maintaining research interviewer proficiency) into a study protocol contribute to more accurate responding (Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & Del Boca, 2000; Laforge, Borsari & Baer, 2005), and such procedures were included into this survey’s protocol, thereby reducing this concern. Additionally, certain sub-populations (i.e., the institutionalized population) were not included in the study protocol raising possible concerns about the generalizability of the data. However, the data is fairly representative and is weighted appropriately to ensure accurate estimates of the population. Another possible limitation includes the reliance on the K6 scale. Although specific types of mental health disorders could not be ascertained in this study, the K6 scale is a psychometrically validated instrument, and it has been shown to reliably discriminate between those with and without mental health disorders (Kessler et al., 2002, 2003).

In sum, the current study findings provide tobacco control researchers with further areas of inquiry. First, the ability of the K6 scale to be used as a proxy indicator for mental health impairments and its capacity to replicate findings from previous studies with specific diagnosable disorders is critical for reducing time, costs, and efforts in assessing current mental health status at the population level, and we recommend that its utility continue to be assessed. Additionally, increased surveillance of tobacco use among those with mental health impairments at the population level is necessary in order to ensure that this group of smokers is being impacted by recent public health efforts. Lastly, to provide a formal evaluation of the hardening hypothesis among this population, an examination of rates of tobacco use across multiple years is warranted to further understand the relative impact of specific tobacco control policies on this group of tobacco users.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this manuscript were presented at the 2007 Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco’s (SRNT) Annual Conference in Austin, Texas. The current study was funded by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Substance Abuse Policy Research Program (Grant #56397) and from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH: Grant #1R03MH077273-01A1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton R, Del Boca F. Talk is cheap: measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Morissette SL, Gulliver SB, Wiegel M, Barlow D. Prevalence of smoking in anxiety disorders uncomplicated by comorbid alcohol or substance abuse. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26(2):107. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L, Peters L, Andrews G. Validity of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) psychosis module in a psychiatric setting. Journal of Psychiatry Residence. 1998;32(6):361–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon J, Susce MT, Francisco JD, Rendon DM, Velasquez DM. Variables associated with Alcohol, Drug, and Daily Smoking Cessation in Patients With Severe Mental Illness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1147–1455. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon J, Becona E, Gurpegui M, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Diaz FJ. The association between high nicotine dependence and severe mental illness may be consistent across countries. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):812–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo CD. Smokers’ Choice: What Explains the Steady Growth of Cigar Use in the U.S.? Public Health Reports. 2006;121:116–121. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino GA. Epidemiology of tobacco use in the United States. Oncogene. 2002;21(48):7326–7340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Pinto A, Gutierrez M, Ezcurra J, Aizpuru F, Mosquera F, Lopez P, de Leon J. Tobacco smoking and bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(5):225–228. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, Dahlgren LA. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143(8):993–997. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, D’Souza DC, Menel WE, Pugh KR, Skudlarski P, Krystal JH. Nicotine effects on brain function and functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(8):850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U. Smoking, nicotine dependence and psychiatric comorbidity--a population-based study including smoking cessation after three years. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(3):287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman GD, Morrisette SB, George TP. Co-Morbidity of smoking inpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14:106–123. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, Abelson JM, McGonagle KA, Schwarz N, Kendler KS, Knäuper B, Zhao S. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7(1):33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforge RG, Borsari B, Baer JS. The utility of collateral informants assessment in college alcohol research: Results from a longitudinal prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;29:130–151. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Those Who Continue To Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2003. (NIH Pub. No. 03-5370) [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM. Treatment of Tobacco Use in an Inpatient Psychiatric Setting. Psychiatric Service. 2004;55(11):1265–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RTI. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Sayette MA. Validation of the nicotine dependence syndrome scale (NDSS): a criterion-group design contrasting chippers and regular smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, Rohsenow DJ, Kaplan GB, Swift RM. Cigarette smoking topography in smokers with schizophrenia and matched non-psychiatric controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005 Nov 1;80(2):259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Smoking among psychiatric outpatients: Relationship to substance use, diagnosis, and illness severity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):259–265. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE, Burns DM. Hardening and the hard-core smoker: concepts, evidence, and implications. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(1):37–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Ziedonis DM. Addressing tobacco among individuals with a mental illness or an addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(6):1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]