Abstract

To address whether mdx mice with haploinsufficiency of utrophin (mdx/utrn+/-) develop more severe skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis than mdx mice, to represent a better model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), we performed qualitative and quantitative analysis of skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis in mdx and mdx/utrn+/- littermates. Inflammation was significantly worse in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at age 3 and 6 months and in mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm at age 3 but not 6 months. Fibrosis was more severe in mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm at 6 months, and at this age, mild fibrosis was noted in quadriceps of mdx/utrn+/- but not mdx mice. The findings indicate that utrophin compensates, although insufficiently, for the effects of dystrophin loss with regard to inflammation and fibrosis of both quadriceps and diaphragm muscles in mdx mice. With more severe muscle dystrophy than mdx mice and a longer life span than utrophin-dystrophin-deficient (dko) mice, mdx/utrn+/- mice provide a better mouse model for testing potential therapies for muscle inflammation and fibrosis associated with DMD.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, mouse model, mdx, mdx/utrn+/-, inflammation, fibrosis

1. Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common genetic muscle disease, affecting 1 in 3,500 live male births (1). It is caused by a defect in the dystrophin gene on X-chromosome (2). The disease is characterized by progressive skeletal and cardiac muscle weakness with premature death in the third decade from respiratory and cardiac failure (3). Muscle biopsies from patients with DMD typically display dystrophic changes, including endomysial inflammation and fibrosis (4). Ameliorating muscle inflammation and fibrosis represents an important therapeutic approach for DMD to improve muscle function and clinical phenotype.

Mdx mice, which harbor a nonsense mutation in exon 23 of the dystrophin gene, have been widely used for studying pathophysiology and for exploring potential therapies for DMD. However, the muscular dystrophy phenotype in this mouse model is mild as compared to human DMD. Mdx mice have subtle weakness and a near normal life span. Endomysial inflammation in mdx diaphragm and limb muscles starts to develop at age 3 weeks, peaks in limb muscles at 8-16 weeks, and subsides spontaneously in limb muscles but not diaphragm thereafter (5-8). Progressive endomysial fibrosis only develops in diaphragm (8-10). Therefore, this mouse model does not completely recapitulate the human DMD phenotype, which somewhat limits its usefulness for testing potential therapies. To improve this mouse model, mice deficient in both dystrophin gene and its autosomal homolog utrophin gene (dko mice) were generated (11, 12). Dko mice display early onset of muscle dystrophy, severe muscle weakness, joint contracture, growth retardation, and premature death around 10 weeks of age, features which phenotypically mimick human DMD. However, the early death of dko mice makes these mice difficult to obtain or maintain. In addition, although the onset of muscle dystrophy is earlier in dko mice, the diaphragm pathology, including the number of necrotic fibers (11), the percentage of newly regenerated fibers (11), and endomysial fibrosis (our unpublished data), is similar in mdx and dko mice at 10 weeks of age before dko mice usually die. Therefore, dko mice are not ideal for testing therapies. A mouse model intermediate in severity between mdx and dko mice would carry significant advantages for testing anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic therapies. We hypothesize that mdx/utrn+/- mice, which survive much longer than dko mice, may develop more severe skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis than mdx mice, and might represent a model with these advantageous characteristics. To address this hypothesis, we quantified and compared the severity of inflammation and fibrosis in quadriceps and diaphragm muscles of mdx and mdx/utrn+/- male littermates at 3 and 6 months of age.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and muscles

Six pairs of mdx and mdx/utrn+/- male littermates were obtained from breeding of mdx/utrn+/- mice (C57Bl/10) (11). Three pairs were sacrificed at age 3 months and three pairs at 6 months. Quadriceps and diaphragm muscles of these mice were collected for histopathological and immunohistochemical studies as well as hydroxyproline content measurements. We followed the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals of Cleveland Clinic and Case Western Reserve University.

2.2. Histopathological analysis

Muscle tissue was fresh-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, sectioned at 8 micron (μm), stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and viewed under a bright field microscope.

2.3. Immunostaining

Eight μm cryostat sections of fresh frozen muscle tissue were blocked in 5% normal rabbit (for CD45 immunostaining) or donkey (for collagen III immunostaining) serum at room temperature for 1 hour followed by incubation in primary antibodies against mouse CD45 (Serotec, UK) or collagen III (Southern Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C. For CD45 immunostaining, the sections were then incubated in biotinylated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature for 1 hour followed by incubation with ABC (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Antibody binding was visualized with DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and viewed under a light microscope. For collagen III immunostaining, following the primary antibody incubation, the sections were incubated in FITC-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (Sigma) at room temperature for 1 hour. Antibody binding was visualized under a fluorescent microscope.

2.4. Quantification of inflammation

Quantitative analysis of inflammation was performed by determining CD45 immunoreactivity as previously described (13). CD45 immunoreactivity, defined as area occupied by reaction product except for normal endomysial capillaries and expressed as a percentage of total muscle cross section area, was calculated on digitized images using an integrated image analysis system attached to a microscope (Olympus BX41). Serial sections were obtained from quadriceps and diaphragm muscles. Eight sections, representing one out of every five sections, of each sample were used for CD45 immunostaining. Immunostained muscle sections, with each section containing five nonoverlapping fields of view, were digitized under a 10× objective, using a 3-CCD color video camera interfaced with Sport Image analysis software. Digitized images were analyzed using the National Institute of Health Image J1.34 software. An area measurement analysis procedure was established to determine the proportion of immunoreactivity area within each fixed field of view. These parameters were then held constant for each set of images obtained at equal objectives and light sensitivities on slides that were processed at one session. The data represented the mean area occupied by immunoreactivity and were expressed as a percentage of total quadriceps or diaphragm cross section area.

2.5. Hydroxyproline assay

Hydroxyproline content was measured according to the protocol described previously (14). Briefly, muscle samples were homogenized thoroughly in distilled water with a final tissue concentration of 20 mg/ml. Duplicates of each sample and standard hydroxyproline solution were used for the assay. Twenty-five μl of each sample and standard hydroxyproline solution (2-20 ug/25 μl) were mixed with equal volume of sodium hydroxide (2N final concentration) and were then hydrolyzed by autoclave at 120°C for 20 minutes. Oxidation was taken at room temperature for 25 minutes by adding 450 μl of chloramine-T to each sample and mixing gently. This was followed by adding 500 μl of Ehrlich's aldehyde reagent to each sample and incubating the samples at 65°C for 20 minutes to develop the chromophore. Absorbance of each sample was read at 550 nm using a spectrophotometer. Hydroxyproline content of each sample was calculated using the standard hydroxyproline curve.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Differences in percentage of inflammation area and mean hydroxyproline content between different groups were evaluated by Student t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Endomysial inflammation was more severe in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps and diaphragm

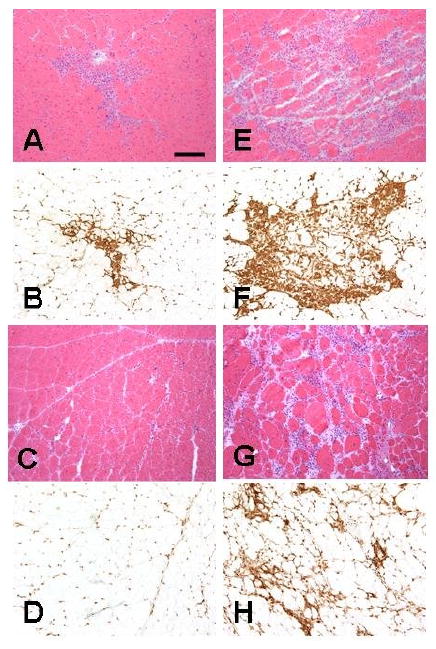

At age 3 months, mdx quadriceps showed multiple endomysial foci of mononuclear inflammatory cells (Fig.1A) which were stained positive for CD45 (Fig.1B); the inflammatory foci were larger in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps (Fig.1E, F) than in mdx quadriceps (Fig. 1A, B). The area occupied by inflammatory cells was higher in mdx/utrn+/- (Mean±SD: 35.2%±4.4) than in mdx mice (6.1%±1.1, p<0.01) (Fig. 3). At 6 months, endomysial inflammation was reduced in mdx quadriceps, and only scattered endomysial inflammatory cells were present. Some small central nucleated regenerated muscle fibers were observed, but there was no myofiber degeneration or necrosis (Fig.1C, D). In contrast, mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at this stage showed marked fiber size variation and multiple small-to-medium foci of endomysial inflammation (Fig. G, H). The area occupied by inflammatory cells was significantly increased in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps (15.7%±7.4) as compared to mdx quadriceps (4.4%±1.0, p=0.02) (Fig.3).

Figure 1.

H&E staining (A, E, C, G) and CD45 immunostaining (B, F, D, H) of quadriceps of mdx (A, B, C, D) and mdx/utrn+/- (E, F, G, H) mice showed larger inflammatory foci in mdx/utrn+/- mice (E, F) than in mdx mice (A, B) at 3 months and persistent moderate degree of endomysial inflammation in mdx/utrn+/- mice at 6 months (G, H) in contrast to largely resolved inflammation in mdx littermates (C, D). Bar=25 μm.

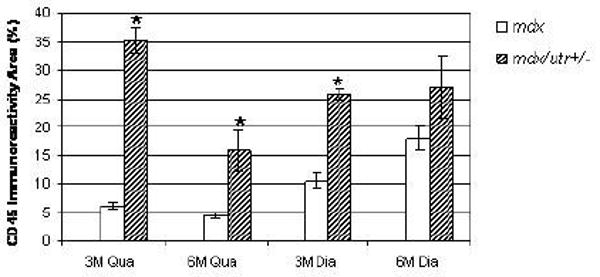

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing significantly higher percentages of CD45 positive inflammation area in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at 3 and 6 months and mdx/utr+/- diaphragm at 3 months than in mdx mice. *p<0.05

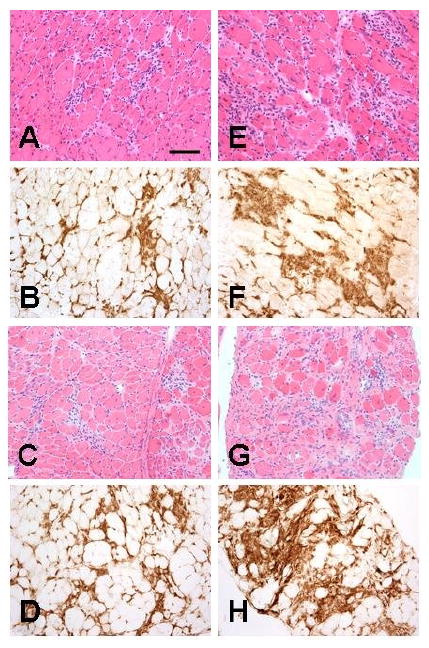

Both mdx and mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm showed multiple small-to-medium foci of endomysial inflammation at 3 months as shown by H&E staining (Fig 2A, E) and highlighted by CD45 immunostaining (Fig.2B, F). At 3 months, diaphragmatic inflammation in mdx/utrn+/- mice was more severe than in mdx animals, with a greater area occupied by inflammatory cells (25.7%±1.9) as compared with mdx mice (10.6%±2.4, p<0.01) (Fig. 3). At 6 months, a moderate degree of inflammation persisted in diaphragm, unlike quadriceps, of both mdx (Fig. 2C, D) and mdx/utrn+/- mice (Fig.2G, H). At this time point, an equivalent area within diaphragm was occupied by inflammatory cells in diaphragms of mdx/utrn+/- mice (26.9%±9.6) as compared to mdx (18.0%±4.3) mice (Fig.3).

Figure 2.

H&E staining (A, E, C, G) and CD45 immunostaining (B, F, D, H) of diaphragm showed larger inflammatory foci in mdx/utrn+/- mice (E, F, G, H) than in mdx mice (A, B, C, D) at 3 months (A, B, E, F) and 6 months (C, D, G, H). Bar=25 μm.

3.2. Mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps developed mild endomysial fibrosis at 6 months

Fibrosis entails excessive collagen deposition. Collagen contains Gly-X-Y repeats and Y is usually hydroxyproline. Therefore, we used collagen III immunostaining and hydroxyproline content measurements to qualitatively and quantitatively assess endomysial fibrosis.

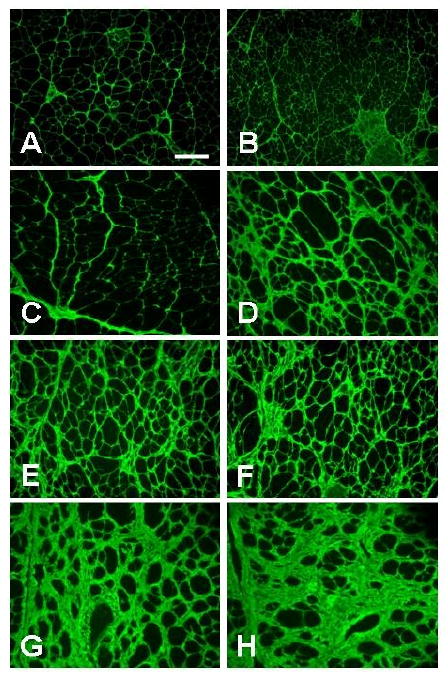

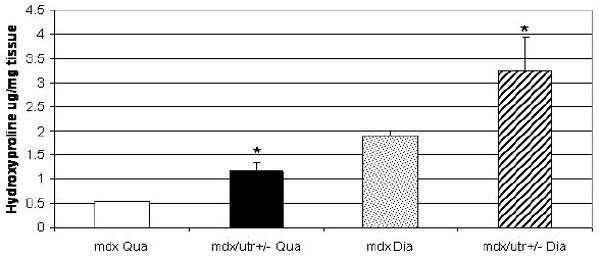

Mdx quadriceps showed a normal pattern of collagen III immunostaining at 3 (Fig.4A) and 6 (Fig.4C) months. Mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at 3 months also showed normal collagen deposition without endomysial fibrosis (Fig. 4B). However, endomysial fibrosis was evident in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at 6 months with increased collagen III deposition (Fig. 4D) and a significantly higher mean hydroxyproline content (μg/mg muscle tissue) (1.16) than that of mdx quadriceps (0.53, p=0.02) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Collagen III immunostaining of mdx (A, C, E, G) and mdx/utrn+/- (B, D, F, H) quadriceps (A, B, C, D) and diaphragm (E, F, G, H) showed mild fibrosis with increased collagen deposition in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps at 6 months (D) but not 3 months (B) or in mdx quadriceps at 3 (A) or 6 months (C). Fibrosis was also present and comparable in mdx (E) and mdx/utrn+/- (F) diaphragm at 3 months, and worse at 6 months with more collagen deposition in mdx/utrn+/- (H) than in mdx mice (G). Bar=25 μm.

Figure 5.

Bar graph showing significantly higher hydroxyproline contents in mdx/utrn+/- quadriceps and diaphragm at 6 months than in mdx mice. *p<0.05

3.3. Endomysial fibrosis was more severe in mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm

Both mdx and mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm developed progressive endomysial fibrosis with increased collagen III deposition (Fig. 4). The degree of fibrosis was comparable in the two mouse strains at 3 months (Fig.4E, F), but was more severe in mdx/utrn+/- mice at 6 months, with markedly increased collagen III deposition (Fig.4H) as compared to mdx mice (Fig.4G). Consistent with the morphological findings at 6 months, the mean hydroxyproline content of mdx/utrn+/- diaphragm (3.27 μg/mg muscle tissue) was significantly higher than that of mdx diaphragm (1.90, p=0.03) (Fig. 5).

4. Discussion

This study shows that haploinsufficiency of utrophin gene worsens inflammation and fibrosis in quadriceps and diaphragm muscles of mdx mice. The finding supports a compensatory role of utrophin for the effects of dystrophin loss on skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis. The finding also suggests that mdx/utrn+/- mice will provide advantages, as a mouse model of DMD, as compared with either mdx or dko mice, for testing anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic therapies.

Consistent with a compensatory role for utrophin, the onset of muscle dystrophic changes in mdx mice corresponds to the time when utrophin disappears from sarcolemma and localizes at the neuromuscular junction. Overexpression of utrophin in skeletal muscle restored dystrophin protein complex (DPC) and rescued the muscular dystrophy phenotype in a dose-dependent manner in mdx mice (15)(16). These findings suggest that dystrophin and utrophin can exert similar functions once distributed to the sarcolemma, and the mild muscular dystrophy phenotype in mdx mice is probably due to the compensation by endogenous utrophin. Consistent with this hypothesis, dko mice, lacking both dystrophin and utrophin, show many features of human DMD, including premature death. Although dko mice do show more severe functional abnormalities of muscle than mdx mice (17, 18), the cause of death in dko mice remains elusive. Myofiber necrosis, regeneration, and fibrosis in diaphragm muscles are not significantly different between mdx and dko mice (11 and our unpublished data) at 10 weeks of age when dko mice usually die. Because of this early death of dko mice, it is not entirely clear to what extent utrophin compensates for the effects of dystrophin loss on diaphragm muscle necrosis and fibrosis.

In the current study, we compared limb and diaphragm muscle inflammation and fibrosis in mdx/utrn+/- and mdx mice at 3 and 6 months of age. Mdx/utrn+/- mice are indistinguishable from mdx mice by size and weight; they do not show the same behavioral signs as dko mice. However, both skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis are more severe in mdx/utrn+/- mice than in mdx mice. The findings support the hypothesis that utrophin compensates for the effects of dystrophin loss on skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis, probably through interactions with other protein components involved in the DPC. Haploinsufficiency of utrophin may compromise its compensatory function, which leads to more impairment of sarcolemmal integrity and subsequent more severe skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis in mdx/utrn+/- mice. However, functional compensation provided by utrophin is incomplete, as mdx mice do develop mild muscular dystrophy.

We propose that mdx/utrn+/- mice may represent a better mouse model than mdx and dko mice for testing chronic anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic therapies. Inflammation and fibrosis are prominent pathological features in muscle tissue of patients with DMD. Ameliorating these pathological changes represents an important therapeutic strategy to improve muscle function in DMD. The widely used mouse model, mdx mice, displays a mild phenotype, in which inflammation spontaneously subsides in the limb muscles and slowly progressive fibrosis only occurs in the diaphragm muscle. Although dko mice display all clinical features of human DMD, they die too early to develop significant diaphragm fibrosis (11, 12). These models are not ideal for testing therapies. Our results indicate that mdx/utrn+/- mice may well represent a DMD mouse model which carries significant advantages for testing chronic anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic therapies. First, mdx/utrn+/- mice develop more severe skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis, and the progression of diaphragm fibrosis is faster than mdx mice. These attributes are advantageous for testing anti-inflammatory strategies to prevent or reduce fibrosis. Second, mdx/utrn+/- mice survive much longer than dko mice, which allows significant diaphragm fibrosis to develop. Based on our observations, mdx/utrn+/- mice can live beyond 1 year of age, which is permissive for testing chronic anti-fibrotic therapies. Third, it is easier to obtain and maintain mdx/utrn+/- mice than dko mice, due to early death of the latter strain. For these reasons, although the genetic deficit in mdx/utrn+/- mice is not identical to human DMD, this mouse model is potentially more useful than mdx and dko mice for testing therapeutic interventions to preclude muscle inflammation and fibrosis associated with DMD.

Acknowledgments

Work supported by 1K08 NS049346-01A2 (LZ).

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Emery AE. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases--a world survey. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90039-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig M, Hoffman EP, Bertelson CJ, Monaco AP, Feener C, Kunkel LM. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell. 1987;50(3):509–17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery AEH. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.K G. Structural and molecular basis of skeletal muscle disease. Basel: ISN Neuropath Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carnwath JW, Shotton DM. Muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: histopathology of the soleus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. J Neurol Sci. 1987;80(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulton GR, Morgan JE, Partridge TA, Sloper JC. The mdx mouse skeletal muscle myopathy: I. A histological, morphometric and biochemical investigation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1988;14(1):53–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1988.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen MJ, Jaros E. Ultrastructure of the skeletal muscle in the X chromosome-linked dystrophic (mdx) mouse. Comparison with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988;77(1):69–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00688245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou L, Porter JD, Cheng G, Gong B, Hatala DA, Merriam AP, et al. Temporal and spatial mRNA expression patterns of TGF-beta1, 2, 3 and TbetaRI, II, III in skeletal muscles of mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(1):32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont-Versteegden EE, McCarter RJ. Differential expression of muscular dystrophy in diaphragm versus hindlimb muscles of mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15(10):1105–10. doi: 10.1002/mus.880151008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stedman HH, Sweeney HL, Shrager JB, Maguire HC, Panettieri RA, Petrof B, et al. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991;352(6335):536–9. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deconinck AE, Rafael JA, Skinner JA, Brown SC, Potter AC, Metzinger L, et al. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90(4):717–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grady RM, Teng H, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90(4):729–38. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Huang D, Matsui M, He TT, Hu T, Demartino J, et al. Severe disease, unaltered leukocyte migration, and reduced IFN-gamma production in CXCR3-/-mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4399–409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy GK, Enwemeka CS. A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clin Biochem. 1996;29(3):225–9. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafael JA, Brown SC. Dystrophin and utrophin: genetic analyses of their role in skeletal muscle. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;48(34):155–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000201/15)48:3/4<155::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinsley J, Deconinck N, Fisher R, Kahn D, Phelps S, Gillis JM, et al. Expression of full-length utrophin prevents muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Nat Med. 1998;4(12):1441–4. doi: 10.1038/4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deconinck N, Rafael JA, Beckers-Bleukx G, Kahn D, Deconinck AE, Davies KE, et al. Consequences of the combined deficiency in dystrophin and utrophin on the mechanical properties and myosin composition of some limb and respiratory muscles of the mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 1998;8(6):362–70. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(98)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen PM, Hiranandani N, Mays TA, Rafael-Fortney JA. Utrophin deficiency worsens cardiac contractile dysfunction present in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(6):H2373–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00448.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]