Summary

Chromosomes that harbor dominant sex determination loci are predicted to erode over time—losing genes, accumulating transposable elements, degenerating into a functional wasteland and ultimately becoming extinct. The Drosophila melanogaster Y chromosome is fairly far along this path to oblivion. The few genes on largely heterochromatic Y chromosome are required for spermatocyte-specific functions, but have no role in other tissues. Surprisingly, a recent paper shows that divergent Y chromosomes can substantially influence gene expression throughout the D. melanogaster genome.(1) These results show that variation on Y has an important influence on the deployment of the genome.

It seems reasonable to assume that the influence of a particular chromosome or region on the rest of the genome should relate to the number and type of genes that it contains. Sex chromosomes have unusual gene content and have been the focus of intense gene expression studies over the last few years.(2) A new study, which explores variation on the Y chromosomes of D. melanogaster, shows that Y chromosomes have many effects on gene expression throughout the genome despite being gene poor.(1) These surprising new findings are counterintuitive.

Sex chromosomes evolve from an ordinary autosome pair via the acquisition of a dominant sex determination gene.(2,3) When the sex-determining gene promotes male fate, the chromosome is a Y. While recombination between the Y and X is suppressed in males, recombination between the X chromosomes in females is not. Suppressed recombination, which is believed to arise due to the accumulation of sexually antagonistic genes linked to the sex determination locus and is irreversibly set by trapping those genes in an occasionally arising inversion, allows deleterious mutations to accumulate on the Y chromosome via Mueller’s ratchet. In the absence of recombination, there is no way to separate linked favorable and unfavorable loci or alleles. Consequently, the Y chromosome accumulates dead genes, transposon insertions and repeat expansions. This model of sex chromosome evolution produces a clear prediction: the Y chromosome will degrade over time turning into a functional wasteland while the X will retain functional homologs. This degradation appears to be very rapid.(4,5) The ultimate fate of the Y chromosome is the transfer of vital functions to other locations in the genome and disappearance all together. Implicit in this view is that the Y chromosome will be less consequential for fitness as these functions are transferred. However, Y chromosomes are common among species, suggesting that they have persistent functions too.

There are only about 20 known protein coding genes on the D. melanogaster Y chromosome.(6) All of the sex determination functions have migrated, as XX and XXY flies are females and XY and X0 flies are males.(7) The excellent viability of XO flies and the excellent viability and fertility of XXY flies also demonstrate that there are no overt non-sex-related functions encoded on the Y chromosome. XO males make sperm, but the sperm heads do not undergo compaction during maturation—a modest role for a chromosome bearing about 20% of the D. melanogaster genome (but only 0.2% of the genes).(8) However, there is clear evidence that variation on Y chromosomes has phenotypic consequences. For example, the Y chromosome of D. melanogaster has a major effect on the total fitness of males,(9) and contributes to mechanisms of sex ratio distortion.(10)

Population-specific Y chromosomes influence gene expression

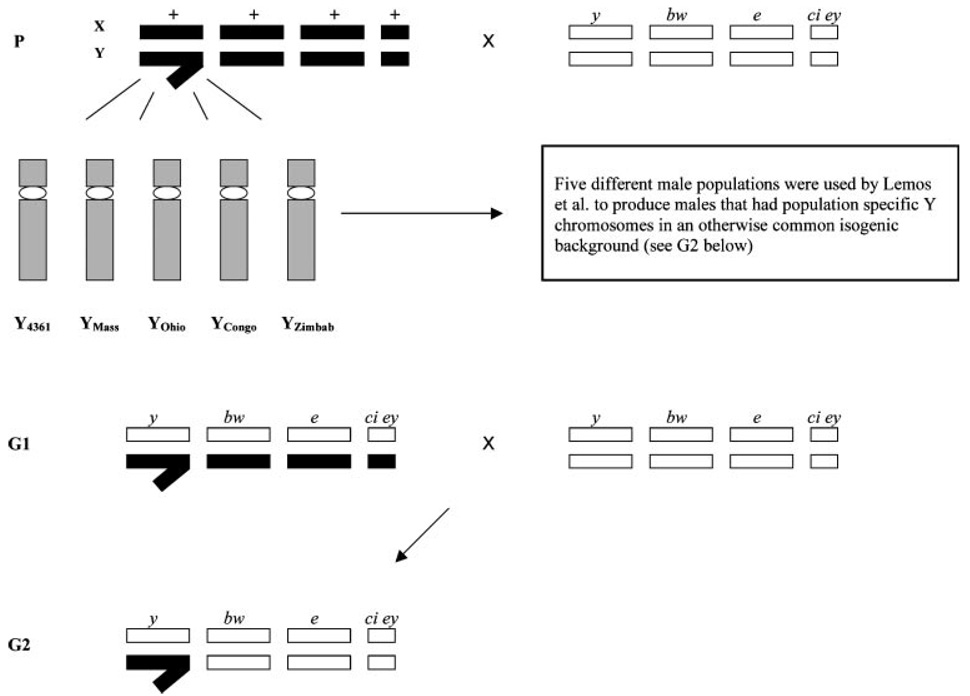

To determine how much influence the Y chromosome has on global transcription, Lemos et al.(1) introgressed specific Y chromosomes from widely separated populations of D. melanogaster into a common genomic background. They maximized putative variation on the Y chromosome by selecting populations that were from diverse and geographically distant environments (temperate and tropical climates). Their experiment involved crossing males from a particular population with females from an isogenic fly stock that had recessive markers for each chromosome (Fig. 1). Males from this F1 generation were then crossed again with the original female marker strain and this provided individuals that had a Y chromosome from a particular population in an otherwise invariant genetic background. Microarray experiments were used to compare gene expression profiles from whole flies among the different introgression lines in addition to control crosses. This experiment provided an unequivocal way to measure directly the effect of Y chromosome variation on the expression of genes throughout the genome. Surprisingly, 100 to 1000 genes are differentially expressed in males that only differ at the Y.

Figure 1.

Crossing scheme used to produce population-specific Y chromosomes introgressed into a common isogenic background. Males from five different fly populations (Y4361, Ymass, YOhio, YMass, YZimbab) were each crossed with females that had recessive markers on each chromosome (strain number 4361- y=yellow on X chromosome; bw=brown on chromosome 2; e=ebony on chromosome 3; ci=cubitus interrupts on chromosome 4 and ey=eyeless on chromosome 4). In the first generation (G1), all flies were heterozygous and theseG1maleswere then backcrossed with females. Males homozygous recessive for all markers and that contained population-specific Y chromosomes were then selected for gene expression analysis.

Adaptive variation on the Y chromosome has previously been attributed to variation in the thermal sensitivity of spermatogenesis. Since Y chromosome variability has a marked effect on the expression of genes throughout the genome, one reasonable hypothesis is that the influence of the Y on gene expression is connected to thermal sensitivity. Lemos et al. used their Y chromosome introgression lines to manipulate temperature on the chromosome background and then surveyed possible insults to gene expression. As predicted, tropical Y chromosome flies reared at cooler temperatures suffer more gene misexpression compared to flies bearing temperate Y chromosome.

Mechanisms of the functional Y

How can a relatively degenerate and transcriptionally inactive chromosome exert such wide influence? Such gene expression changes are commonly associated with transcription factors; however, there are no known transcription factors located on the Y chromosome. The changes in expression are likely to be due to some combination of feedback related to the relatively few structural genes encoded on the Y, the very large bulk of heterochromatin on the degenerating Y chromosome, or the unusual gene structure of Y chromosome genes.

There is a great deal of indirect evidence that global expression divergence is due to Y chromosome transcription. Male gene expression differs more within and between species of Drosophila than those expressed in females(11,12) and most of the male-biased expression is due to the germline.(13) Lemos et al. found that transcriptional variation due to Y chromosomes was enriched for genes that were more highly expressed in males and expressed at lower levels in females. Many genes are differentially expressed between species of Drosophila and genes affected by variation in Y chromosomes are the same ones that are most divergently expressed between species. These data may suggest that forces shaping the degradation of the Y also contribute to functional connectivity for the few genes that are located on Y.(14) If Y-linked genes that encode proteins have a particularly rich set of interacting proteins, they could have a large effect on the expression of other genes as the result of feedback mechanisms.

Y chromosome genes are only transcribed in the male germline, so one way of more directly determining if transcription is involved, would be to ask if the trans-effects of Y chromosome variation are restricted to the germline. These experiments will be important because it is clear that the amount of Y heterochromatin strongly influences expression of genes near heterochromatic blocks elsewhere in the genome.(15) If Y chromosome gene expression, which is germline restricted, results in global expression divergence, then XXY females should be unaffected. Similarly, somatic tissues of XY males should not show changes due to the particular Y chromosome that they bear. If Y chromosome heterochromatin polymorphisms are responsible, then male somatic tissues and females with Y chromosomes should also show some altered global expression patterns.

Heterochromatin also plays a role in silencing the activity of transposable elements and the Y chromosome is mostly filled with transposable elements and repetitive sequences. Transposable elements on the Y chromosome might be effectively controlled in the original host genome, but might become unleashed in the presence of foreign autosomes. Lemos et al.(1) find a surprising number of transposable elements represented in their dataset raising the possibility of Y-dependent transposon derepression due to hybridization and ingression.

The effect of Y chromosomes on the rest of the genome could also be a consequence of transcription in a highly heterochromatic chromosome. The Y chromosome genes have fairly typical exons separated by enormous introns.(16) Transcription through these introns seems likely to be a substantial challenge, which may deplete the spermatocyte of transcriptional cofactors. Thus varied intron length could well influence the titration of these cofactors and thus have dramatic secondary effects on transcription throughout the genome.

Another hypothesis for how the Y could be exerting control on the rest of the genome is through effects on the spatial organization of the genome itself. Recent work suggests that spatial positioning of genes and chromosomes can influence gene expression.(17) Polymorphic nuclear organization has not been explored. Whatever the mechanisms may be, understanding how variation on Y chromosomes influences patterns of gene expression throughout the genome will be an important future challenge for genome and evolutionary biologists.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eugene Koonin for reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Funding agency: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

References

- 1.Lemos B, Araripe LO, Hartl DL. Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences. Science. 2008;319:91–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1148861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B. Sex chromosomes: evolution of the weird and wonderful. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R129–R131. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinemann S, Steinemann M. Y chromosomes: born to be destroyed. Bioessays. 2005;27:1076–1083. doi: 10.1002/bies.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachtrog D, Hom E, Wong KM, Maside X, de Jong P. Genomic degradation of a young Y chromosome in Drosophila miranda. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R30. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturgill D, Zhang Y, Parisi M, Oliver B. Demasculinization of X chromosomes in the Drosophila genus. Nature. 2007;450:238–241. doi: 10.1038/nature06330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson RJ, Goodman JL, Strelets VB. FlyBase: integration and improvements to query tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D588–D593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridges CB. Non-disjunction as proof of the chromosome theory of heredity. Genetics 1916. 1916;1:1–52. doi: 10.1093/genetics/1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlesworth B. Genome analysis: More Drosophila Y chromosome genes. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R182–R184. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chippindale AK, Rice WR. Y chromosome polymorphism is a strong determinant of male fitness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5677–5682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101456898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montchamp-Moreau C, Ginhoux V, Atlan A. The Y chromosomes of Drosophila simulans are highly polymorphic for their ability to suppress sex-ratio drive. Evolution Int J Org Evolution. 2001;55:728–737. doi: 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0728:tycods]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiklejohn CD, Parsch J, Ranz JM, Hartl DL. Rapid evolution of male-biased gene expression in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9894–9899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630690100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Sturgill D, Parisi M, Kumar S, Oliver B. Constraint and turnover in sex-biased gene expression in the genus Drosophila. Nature. 2007;450:233–237. doi: 10.1038/nature06323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parisi M, Nuttall R, Edwards P, Minor J, Naiman D, et al. A survey of ovary-, testis-, and soma-biased gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster adults. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-6-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachtrog D. Evidence that positive selection drives Y-chromosome degeneration in Drosophila miranda. Nat Genet. 2004;36:518–522. doi: 10.1038/ng1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimitri P, Pisano C. Position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: relationship between suppression effect and the amount of Y chromosome. Genetics. 1989;122:793–800. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carvalho AB, Vibranovski MD, Carlson JW, Celniker SE, Hoskins RA, et al. Y chromosome and other heterochromatic sequences of the Drosophila melanogaster genome: how far can we go? Genetica. 2003;117:227–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1022900313650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]