Abstract

By methylation of peptide arrays, we determined the specificity profile of the protein methyltransferase G9a. We show that it mostly recognizes an Arg-Lys sequence and that its activity is inhibited by methylation of the arginine residue. Using the specificity profile, we identified new non-histone protein targets of G9a, including CDYL1, WIZ, ACINUS and G9a (automethylation), as well as peptides derived from CSB. We demonstrate potential downstream signaling pathways for methylation of non-histone proteins.

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression by covalent modification of histone proteins and methylation of DNA controls development and disease processes1. Post-translational modification of histone proteins includes acetylation, phosphorylation and methylation. Many of these modifications occur on the N-terminal tails of the histone proteins that protrude from the nucleosome. Methylation of lysine residues in histone tails has been identified in histone H3 lysine residues 4, 9, 27 and 36; in histone H4 lysine 20; and in histone H1b lysine 25. Each of these methylations has different biological functions1.

The first histone lysine methyltransferase was identified in 2000 (ref. 2), and today about 30 different enzymes are known in different species1. Most protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs) contain a SET domain, which harbors the active center of the enzymes3. Here, we investigate the substrate sequence specificity of the human G9a PKMT, which is important for the euchromatic histone H3K9 methylation that is essential for early embryogenesis4, the propagation of imprints5 and control of DNA methylation6. Knockout of G9a results in a decrease of global H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 levels7. In vitro G9a generates mainly H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 (ref. 8), as well as H3K9me3 after long incubation9. In contrast to the Dim-5 and Suv39H1 H3K9 methyltransferases, G9a methylates not only H3K9 but also H3K27 (ref. 10), which implicates different specificities in peptide recognition.

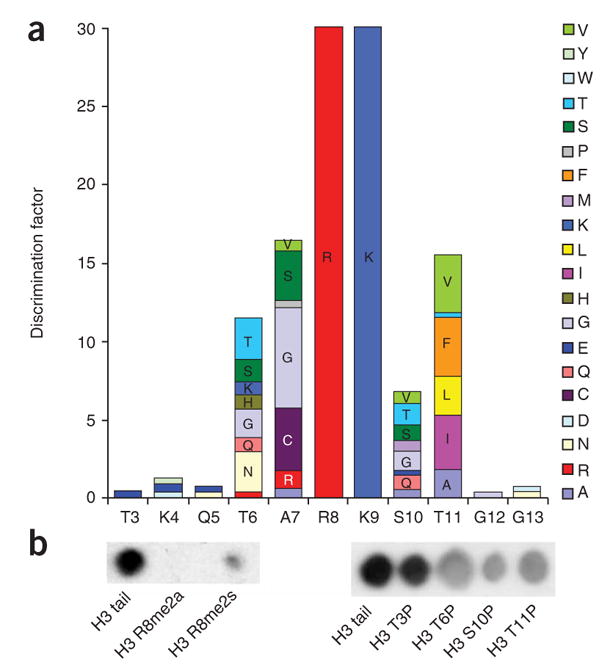

To analyze the substrate specificity of PKMTs, we prepared peptide arrays on functionalized cellulose membranes using the first 21 residues of histone H3 as template11 (Supplementary Methods online). The membranes were incubated with G9a in the presence of radioactively labeled [methyl-3H]-S-adenosyl-L-methionine (3H-AdoMet, 1), and the transfer of methyl groups to the immobilized peptides was detected by autoradiography (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). To quantify the contribution of each amino acid to the recognition of the substrate and display it graphically, the discrimination factor of G9a at each position was calculated (Fig. 1a). The results showed that G9a interacts with H3 residues 6–11, which agrees with a report describing a heptapeptide of the histone H3 tail (TARKSTG) as the minimal substrate methylated by G9a (ref. 12). In addition to Lys9 (the target of methylation), Arg8 is the most important specificity determinant for G9a. Any other amino acid substituted at that position completely abolished the activity of G9a on the H3 peptide substrate. The enzyme did not exhibit strong specificity for any of the other positions (Fig. 1a). At position 6, threonine and asparagine were preferred, but they could be substituted by a variety of hydrophilic amino acids. The residue at position 7 was relatively more important, because only three amino acids are recognized efficiently (glycine, cysteine and serine). Arginine and alanine were the next best residues, which indicates a preference for small amino acids (glycine, alanine, serine and cysteine are the smallest among the 20 residues). At position 10, several mostly hydrophilic residues are accepted, whereas the hydrophobic amino acids (phenylalanine, isoleucine, valine, leucine and alanine) are favored at position 11. Consistent with this specificity profile, G9a methylated the H3K27 and H1bK25 peptides in addition to the H3K9 peptide, but it did not methylate the H4K20 peptide, which carries a large side chain at position 7 (histidine) and a hydrophobic side chain at position 10 (valine) (Supplementary Table 1 online). We note that all three histone peptide substrates contain an alanine at position 7, although it was not favored by the discrimination factor at this position.

Figure 1.

Specificity analysis of human G9a SET domain. (a) Bar diagram showing the discrimination factors of G9a catalytic SET domain. The specificity of G9a catalytic SET domain was tested on 20 × 21 peptide arrays using the first 21 residues of histone H3 as template. Each residue was exchanged against all 20 natural amino acids, and the relative efficiency of methylation was analyzed. Specificity factors were calculated as described in Supplementary Methods. (b) Methylation of H3 tail peptides carrying preexisting modifications.

In agreement with the high importance of Arg8 for substrate recognition of G9a, peptides that carry an asymmetric dimethylation of Arg8 were not methylated by G9a, and peptides that carry symmetric dimethylation of Arg8 were methylated with an 85% (±5%) reduced level (Fig. 1b). The interplay between H3R8 methylation by PRMT5 (ref. 13) and H3K9 methylation by G9a may be an analogy to the mutually exclusive effect of H3R2 methylation by PRMT6 and H3K4 methylation by MLL methyltransferase activity14,15. Since the exchange of Thr6 or Thr11 by glutamate strongly inhibited G9a (Fig. 1a), we investigated the effect of H3 tail phosphorylation on the activity of G9a. Peptides phosphorylated at Thr6, Ser10 or Thr11 were methylated with an approximately 50% reduced level, whereas phosphorylation of Thr3 had no effect (Fig. 1b). Therefore, G9a differs from other H3K9 methyltransferases, such as human Suv39H1, whose activity is more strongly inhibited by Ser10 phosphorylation2.

Methylation and demethylation of non-histone proteins at lysine residues have been observed previously in some cases (Supplementary Discussion online). The main specificity for an Arg-Lys dipeptide together with some deviations of G9a preferences from the H3 tail sequence at positions 7 and 11 (−2 and +2 with respect to the target Lys9) suggested that G9a might methylate additional non-histone substrates as well. A Scansite search (http://scansite.mit.edu/) with the G9a specificity profile resulted in 92 human proteins containing potential target sites. 18 of them that have known nuclear localization were selected for further analysis. In addition, we retrieved proteins known to interact with G9a and searched for Arg-Lys sequences. We identified 13 additional candidates including a potential site for automethylation of G9a in the N-terminal part of the enzyme (the catalytic SET domain is located in the C-terminal part). Because some of the potential target proteins had more than one Arg-Lys site, we altogether synthesized 45 peptides in duplicates and tested for methylation by G9a on cellulose membranes. Out of the 45 potential peptide targets, seven were methylated to the same extent as histone H3 peptides and four were methylated to a lower but detectable level (Supplementary Table 1). The strongest methylation was observed with the peptides derived from chromodomain Y-like protein (CDYL1), widely interspaced zinc finger motifs protein (WIZ), Cockayne syndrome group B protein (CSB, which was methylated at four sites) and the N-terminal automethylation site in G9a (confirmed independently16). Weaker methylation was observed with ACINUS, histone deacetylase-1 (HDAC1), DNA methyltransferase-1 (Dnmt1) and Kruppel-like factor-12 (Kruppel).

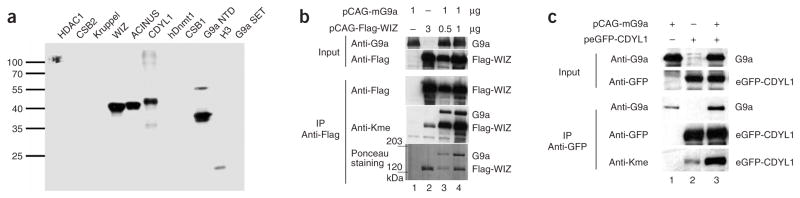

The protein domains containing the new G9a target sites were cloned as GST-fusion proteins, expressed and incubated with the G9a SET domain in vitro, resulting in a strong methylation of WIZ, CDYL1, ACINUS and the N-terminal part of G9a (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2 online). The methylation at the predicted target sites was confirmed by mass spectrometry after proteolytic digestion for CDYL1, WIZ, ACINUS, Dnmt1 and G9a (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Furthermore, methylation of CDYL1 and WIZ, and the G9a automethylation, were also detected by mass spectrometry after their coexpression with G9a catalytic SET domain in Escherichia coli (Supplementary Fig. 4 online), and by an anti-pan methyllysine antibody after their coexpression with G9a in human cells (Fig. 2b,c), which demonstrates that the methylation of non-histone targets also occurs under cellular conditions.

Figure 2.

Methylation of new G9a targets. (a) Detection of protein methylation by transfer of radioactively labeled methyl groups. Purified GST-tagged protein domains were incubated with G9a catalytic SET domain in the presence of radioactively labeled [methyl-3H]-AdoMet and separated on an SDS polyacrylamide gel, and the methylation of the target proteins was analyzed by autoradiography. As a control, methylation of histone H3 (lane 10) is shown. The G9a catalytic SET domain (which does not contain the automethylation site) incubated with 3H-AdoMet is shown in lane 11. The N-terminal domain of G9a is abbreviated as G9a NTD. A Coomassie-stained control gel of the proteins illustrated equal loading (Supplementary Fig. 2). (b) Flag-tagged WIZ was overexpressed together with mouse G9a in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells. Flag-tagged WIZ was immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibody and subjected to western blot analysis. To detect lysine methylation and G9a, anti-pan methyllysine antibodies and anti-G9a antibodies were used. The lysine methylation detected for WIZ was substantially enhanced by coexpression of G9a (compare lanes 3 and 4 with 2). We also recognized G9a automethylation. (c) eGFP-CDYL1 (human CDYL1 residues 64–283) was coexpressed with G9a in HEK 293T cells. The eGFP-CDYL1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-eGFP antibody (Roche) and subjected to western blot analysis. Coimmunoprecipitation of G9a was less efficient than that by the Flag-WIZ shown in b, but eGFP-CDYL1 lysine methylation was clearly enhanced by coexpression of G9a (compare lane 3 with lane 2).

To determine whether the methylation of the new targets could have biological effects, we asked whether reading domains such as the chromodomain of HP1β (recently used in the study of G9a automethylation16) can detect the methylation state of non-histone protein lysine residues. The HP1 chromodomain is known to interact with trimethylated H3K9 (ref. 17), which—together with dimethylation and less frequently monomethylation—is caused by the G9a catalytic SET domain.

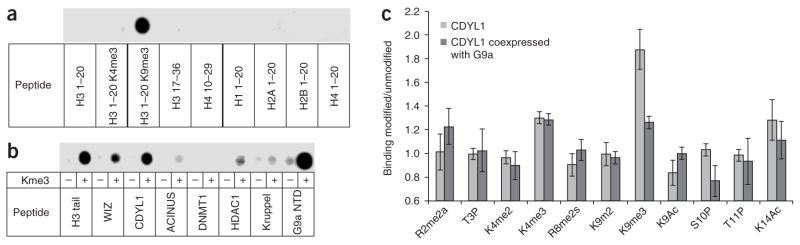

Peptide arrays, previously used to analyze the binding specificity of antibodies18, may also be applicable for analysis of histone tail recognition by reading domains. To validate this approach, an array containing different methylated and unmethylated histone peptides was prepared and incubated with GST-tagged HP1β protein. In agreement with previous reports17, a methylation-specific binding of HP1β to the H3K9me3-containing peptide was observed, but such a binding to H3K4me3 was not observed (Fig. 3a). We compared the binding of HP1β to the trimethylated and unmethylated peptides of the non-histone targets synthesized on cellulose membrane. We detected strong methylation-specific binding of HP1β to the automethylation site of G9a (as seen in ref. 16), and to the peptides derived from H3, CDYL1 and WIZ (Fig. 3b). The methylated peptides derived from HDAC1, ACINUS and Kruppel were weakly bound.

Figure 3.

HP1β binding to modified and unmodified peptides analyzed using peptide arrays. (a) HP1β binding to trimethylated and unmethylated peptides derived from natural histone tails confirming the specificity of HP1β binding to H3K9me3. (b) HP1β binding to trimethylated and unmethylated peptides derived from the newly identified non-histone targets. The automethylation site in the N-terminal domain of G9a is abbreviated as G9a NTD. (c) CDYL1 binding to H3 and H4 tail peptides containing several known modifications in various combinations: R2me2a, T3P, K4me2, K4me3, R8me2s, K9me2, K9me3, K9Ac, S10P, T11P and K14Ac for H3, and K5Ac, K8Ac, K12Ac, K16Ac, K20me2 and K20me3 for H4. The array was incubated with CDYL1, and binding to each spot was quantified. CDYL1 was used in methylated form obtained after coexpression with G9a catalytic SET domain in E. coli (dark gray bars) or in unmethylated form (light gray bars). Whereas unmethylated CDYL1 shows approximately two-fold preferential binding to H3K9me3 peptides, this preference was lost with methylated CDYL1. The graph shows the averages of two independent experiments; error bars indicate the s.d. of the mean.

Since the methylation of the CDYL1 protein occurs at Lys135 near to its chromodomain (residues 59–114), we investigated whether this modification might influence the interaction of the chromodomain with histone tails using an array comprising 410 H3 and H4 tail peptides in various modification states. The array was incubated with CDYL1, and binding to each spot was quantified. To determine the binding preference to any particular modification, the average binding activity to all spots containing the modification was compared with the average binding to all spots not having it. This analysis clearly showed a preferential interaction of CDYL1 with H3K9me3 (Fig. 3c). This preference was not detectable with methylated CDYL1 purified after coexpression with G9a in E. coli (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 4), which indicates that the methylation of CDYL1 abolished the H3K9me3 interaction. These data suggest that the methylated Lys135 in CDYL1 regulates its chromodomain binding with histone H3K9me3 perhaps by blocking its binding pocket for trimethylated lysine.

In conclusion, we show here that the combination of specificity profile analysis and known interaction information is a powerful approach that allowed us to identify several non-histone G9a-mediated methylation targets involved in epigenetic signaling, DNA repair and control of gene expression. Methylation-specific binding of HP1β to non-histone targets indicates that biological effects of the modification could be mediated by regulated binding of reading domains (as established for histone modification), which could have an impact on their cellular functions.

There are several methyl-binding protein modules—the chromodomain, tudor domain, PHD fingers, malignant-brain-tumor domain and ankyrin repeats—that can preferentially bind lysines methylated to specific degrees at specific histone tail residues. It is possible that a reading domain with preference for mono- or dimethylated lysine (the methylation product of G9a in vivo) might specifically interact with G9a-mediated non-histone methylation (Supplementary Discussion). Hence, methylation of non-histone proteins adds a new dimension to epigenetic signaling that could be important for regulating the activity and interaction of chromatin factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The US National Institutes of Health (GM068680) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Biofuture program have supported this work. We thank M.T. Bedford (University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) for the GST-HP1β expression construct and M. Yoshida (RIKEN) for technical advice on anti-pan methyllysine antibodies. Technical assistance by M. Schwerdtfeger (Jacobs University Bremen) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information and chemical compound information is available on the Nature Chemical Biology website.

References

- 1.Kouzarides T. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rea S, et al. Nature. 2000;406:593–599. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng X, Collins RE, Zhang X. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:267–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tachibana M, et al. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1779–1791. doi: 10.1101/gad.989402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xin Z, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14996–15000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikegami K, et al. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tachibana M, et al. Genes Dev. 2005;19:815–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins RE, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5563–5570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410483200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patnaik D, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53248–53258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tachibana M, Sugimoto K, Fukushima T, Shinkai Y. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25309–25317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathert P, Zhang X, Freund C, Cheng X, Jeltsch A. Chem Biol. 2008;15:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin HG, et al. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12998–13006. doi: 10.1021/bi0509907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dacwag CS, Ohkawa Y, Pal S, Sif S, Imbalzano AN. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:384–394. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01528-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirmizis A, et al. Nature. 2007;449:928–932. doi: 10.1038/nature06160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guccione E, et al. Nature. 2007;449:933–937. doi: 10.1038/nature06166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampath SC, et al. Mol Cell. 2007;27:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs SA, Khorasanizadeh S. Science. 2002;295:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1069473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank R. J Immunol Methods. 2002;267:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.