Abstract

Xenografting immunodeficient mice after low-dose irradiation has been employed as a surrogate human hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) assay; however, irradiation requires strict and meticulous animal support and can produce significant mortality rates, limiting the usefulness of this model. In this work, we examined the use of parenteral busulfan as an alternative conditioning agent. Busulfan led to dose dependent human HSC engraftment in NOD/LtSz-scid/IL2Rγnull mice, with marked improvement in survival rates. Terminally differentiated B and T lymphocytes made up most of the human CD45+ cells observed during the initial 5 weeks post transplant when unselected cord blood (CB) products were infused, suggesting derivation from existing mature elements rather than HSCs. Beyond 5 weeks, CD34+-enriched products produced and sustained superior engraftment rates compared with unselected grafts (CB CD34+, 65.8±5.35%, vs. unselected CB 4.27±0.67%, at 24 weeks). CB CD34+ achieved significantly higher levels of engraftment than mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ enriched peripheral blood (PB CD34+). At 8 weeks, all leukocyte subsets were detected, yet human red blood cells (RBCs) were not observed. Transfused human red cells persisted in the chimeric mice for up to 3 days; an accompanying rise in total bilirubin suggested hemolysis as a contributing factor to their clearance. Recipient mouse-derived human HSCs had the capacity to form erythroid colonies in vitro at various time points post-transplant in the presence of human transferrin (Tf). When human Tf was administered singly or in combination with anti-CD122 antibody and human cytokines, up to 0.1% human RBCs were detectable in the peripheral blood. This long evasive model should prove valuable for the study of human erythroid cells.

Keywords: Cord Blood, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, severe combined immunodeficient mice, Transferrin, Xenograft transplant, Busulfan, Erythropoiesis, Hematopoietic stem cells

Introduction

Despite the development of sophisticated in vitro assays for primitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), transplantation assays remain the gold standard for HSC enumeration. Large animals better model human HSCs activity, yet are cumbersome, costly, and outbred yielding high variability. The creation of humanized mice that carry partial or complete human physiological systems may overcome some of these obstacles. Transplantation of human HSCs into immunodeficient mice has been employed as a surrogate HSC assay. HSC xenotransplantation in NOD/SCID mice has proven a useful tool in gaining a better understanding of HSC behavior in vivo1–3. NOD/SCID mice have long been the standard for xenografting human HSCs, but the remaining natural killer (NK) cell activity interfered with efficient human cell engraftment. To reduce residual NK cell activity in recipient xenograft mice, a new strain, NOD/SCID/β2mnull mouse, was established. In this strain, efficient human cell engraftment was observed, however human T cell were not detected in high numbers4, 5. Third generation NOD/LtSz-scid/IL2Rγnull (NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull) mice were subsequently established to overcome these issues6. Another similar strain of mice, NOD/Shi-scid/IL2rγnull, with a truncated or complete null γC mutation has also been reported7, 8. These mice have no lymphocyte or NK cell activity and demonstrate impaired dendritic cell function. When human HSCs are transplanted into these strains after low dose total body irradiation (TBI), T, B and NK cells of human origin are easily detectable in the circulation6–9. In order to further develop this model for gene therapy applications, several remaining issues require further study including optimal conditioning, HSC source, cell dose, graft composition, and the lack of significant human erythroid output observed to date.

To achieve high-level human cell engraftment in the xenograft model, TBI as preconditioning has been nearly exclusively employed; however, the administration of TBI in our facility results in substantial mortality. Moreover, TBI requires strict facility regulation to allow the use of irradiators, often located in areas remote from animal housing. Care of animals following TBI requires autoclaved cages and chow, antibiotic administration, HEPA filtered airflow, and pathogen free conditions to handle the animals. Clinically, TBI has been progressively replaced by the use of combination of chemotherapeutic agents such as busulfan10–12. Thus a simple, convenient, effective and less toxic conditioning regimen remains desirable.

Busulfan (Bu; 1,4-butanediol dimethanesulfonate) is an alkylating agent with predominantly myelosuppressive and minimally immunosuppressive properties that has long been used in human HSC transplantation13. Indeed, busulfan has been extensively employed in experimental animal models14–16, but no reports have demonstrated its use in the NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull strain. Because NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice have a more immature immune system, we hypothesized that only myelosuppression was necessary to achieve human cell engraftment, allowing significant human cell engraftment with busulfan conditioning alone. In this report, we describe our experience with busulfan conditioning in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice, comparing HSC sources, graft composition and conditions for the elusive human erythroid output.

Material and method

Mice

Male NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid IL2rgtm1Wjl/Sz/J (NOD/LtSz-scid/IL2Rγnull, NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, http://www.jax.org) and have been reported elsewhere6. Mice were 7–10 weeks old at the time of transplant. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility and handled according to an animal care and use protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institutes of Health.

Conditioning of NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rγnull Mice for Transplantation

Various doses of busulfan (Busulfex, PDL BioPharma, Redwood City, CA, http://wwww.pdl.com) were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Biofluids, Rockville, NJ) to a final volume 500 ul and injected into recipient mice intraperitoneally. Doses of 10 and 25 mg/kg of busulfan were injected 24 hours before infusion of human cells; 50 mg/kg doses were injected in two equal doses of 25 mg/kg 48 and 24 hours prior. Some mice were injected with 100 ug of anti-CD122 antibody generated from TM-β1 hybridoma cell lines (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) as previously reported17. One group of control mice received low-dose (100–300cGy) total body radiation from a cesium source at 91.7 cGy/min (MDS Nordion, Kanata, Ottawa).

Cell Preparation and Infusion

Cord blood (CB) cells were obtained from eight different normal volunteers during deliveries after written informed consent usinga protocol approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the NIH. Mononuclear cells (MNC) were obtained after density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and red blood cells (RBCs) were removed using ammonium chloride potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Quality Biological Inc, Gaithersburg, MD). CD34 or CD3 enrichment was performed using anti-CD34 or anti-CD3 biotinylated antibody and streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, MA). Cells were passed through the positive selection column twice, and purity was assessed by flow cytometry using phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD34 antibody (clone 563) or anti-human CD3 antibody on a FACS Calibur (all BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Peripheral blood (PB) CD34+ cells were obtained from 10 different healthy adult volunteers (age 18 and older) as previously described18 using a protocol approved by the NIDDK IRB. Briefly, the HSCs were mobilized with 5 days of 10μg/kg recombinant human (rHu) granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA). On day 5 of mobilization, PB CD34+ cells were collected by one 15-liter leukapheresis, and CD34 positive selection was performed using the Isolex 300i automated immunomagnetic system (Nexell, Miltenyi, Auburn, CA).

Donor human cells were suspended in PBS to final volume of 500uL and infused intravenously via tail vein as previously described19. After infusion of donor human cells, murine blood was obtained every 6 days for complete blood counts (CBC) using a Celldyne 3500 automated cell counter (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois).

Flow Cytometric Analysis for Donor Chimerism and Leukocyte Subset

Bone marrow (BM) was harvested as previously described19, and splenocytes were obtained by gently mashing the spleens with forceps through a nylon mesh in Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Media (DMEM, Mediatech, Herdon, VA)20. The splenocytes were then washed and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). BM, spleen, and PB cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human CD45 and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD45; red cells, anti-mouse TER119-FITC and anti-human GPA-PE (CD235a). Leukocyte subsets were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD45 and one of the following: CD14-PE, CD16-PE, CD20-PE, CD3-PE, CD56-PE, CD41-PE, CD61-PE or CD71-PE. B-lymphocyte subsets were stained with CD19-PE and immunoglobulin IgM-FITC or IgG-FITC, and T lymphocytes with CD3-FITC and CD4-PE or CD8-PE. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Colony Forming Unit Assay

BM or spleen cells of chimeric NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice were inoculated at 1×105 cells/mL in 3 different methylcellulose culture media as previously reported 3, 21: MethoCult H4436 (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), which contains human cytokines and transferrin (Tf); MethoCult H4230, supplemented with 5 U/ml recombinant human (rHu) erythropoietin (Epo, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), 10 ng/ml rHu granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF, Sandoz, East Hanover, NJ), 10 ng/ml rHu IL-3, and 100 ng/ml rHu stem cell factor (SCF, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); and MethoCult M3434, which contains murine cytokines and Tf. Plated cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Between days 10 and 14, colonies were counted, and 12 to 36 individual colonies were plucked, digestedwith 20 μg/ml proteinase K (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) at 55 °C for 1 hour, and incubated at 99°C for 10 minutes. The resulting DNA was analyzed for human ALU by nested PCR3 using the following oligonucleotide primers: ALU-5′, CACCTGTAATCCCAGTTT-3′; ALU-3′, CGCGATCTCGGCTCACTGCA. PCR cycles were set at denaturation at 95° for 10 minutes, then 20 cycles of amplification at 95° for 1 minute, 55° for 45 seconds, and 72° for 1 minute.

Red Cell Transfusion

Type “O” red blood cells (RBC) were collected from healthy human volunteers. For each mouse, 1000uL of human unselected blood was centrifuged at 427 g, serum was removed, RBCs were washed twice and diluted with PBS to a final volume of 750uL.

Injection of Human Cytokines for Erythropoiesis

We transplanted additional mice with CB CD34+ cells, and treated them using a variety of cytokine cocktails to mimic in vitro culture conditions: 1) human Tf alone; 2) CFU conditions - human Tf, SCF, EPO, IL3, and GM-CSF; 3) CFU cytokines and anti-human CD122 antibody; 4) erythroid culture conditions - human Tf, SCF, dexamethasone, Epo, and TGF-β; 5) erythroid culture conditions and anti-human CD122.

Sixteen milligrams of human holo-Tf per mouse (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered 3 times a week for 3–5 weeks beginning day 0 (n=3–4, repeated 4 times), 60 (n=3), 120 (n=3), 150 (n=3), or 180 (n=3) post transplant. This dose was calculated based on the upper limit of normal human serum Tf level in the clinical chemistry laboratory, and confirmed by human Tf ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc, Montgomery TX) of mouse serum. In the Day 0 group only, 100ug of human anti-CD122 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) was administered once at the day of transplant; dexamethasone 10−6M (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and cytokines (rHu Epo 20U, SCF 100ng, IL3 10ng, TGF-β 100ng, GM-CSF 10ng) were all administered at days 0, 7, and 14.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Murine whole blood (500 ul) was collected from mice that received transferrin, stained with human GPA and Ter119 antibody, and sorted by FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). The GPA positive cells were pelleted, washed twice, and lysed with water, frozen at −20 for 5 minutes, and thawed at 37C for 5 minutes. Proteins were visualized using a colloidal Coomassie Blue staining kit (Invitrogen), and analyzed using a tandem HPLC-mass spectrometry. Mass from eluted peptides were queried in the Mascot database, and searched for human α- and β-globin chains.

Statistics

All measures of variance are presented as standard errors. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t test with a p value <0.05 deemed significant.

Results

Busulfan and PB CD34+ Dose in Xenograft Transplantation

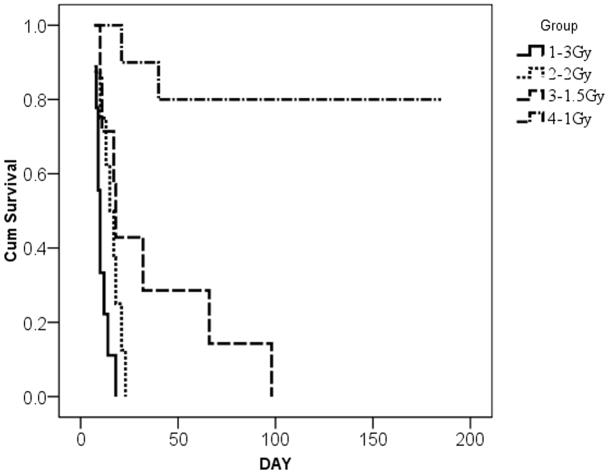

We initially transplanted mice with PB CD34+ cells (2 × 106 cells per mouse) after irradiation with 1 (n=10), 1.5 (n=7), 2 (n=8) and 3 Gy (n=9) but experienced high mortality (Figure 1a). Mortality estimates of 100% were seen at all doses higher than 1 Gy. Human cell engraftment levels after 1 Gy were maximal at 8 weeks and averaged 16.0±1.07% (data not shown).

Figure 1.

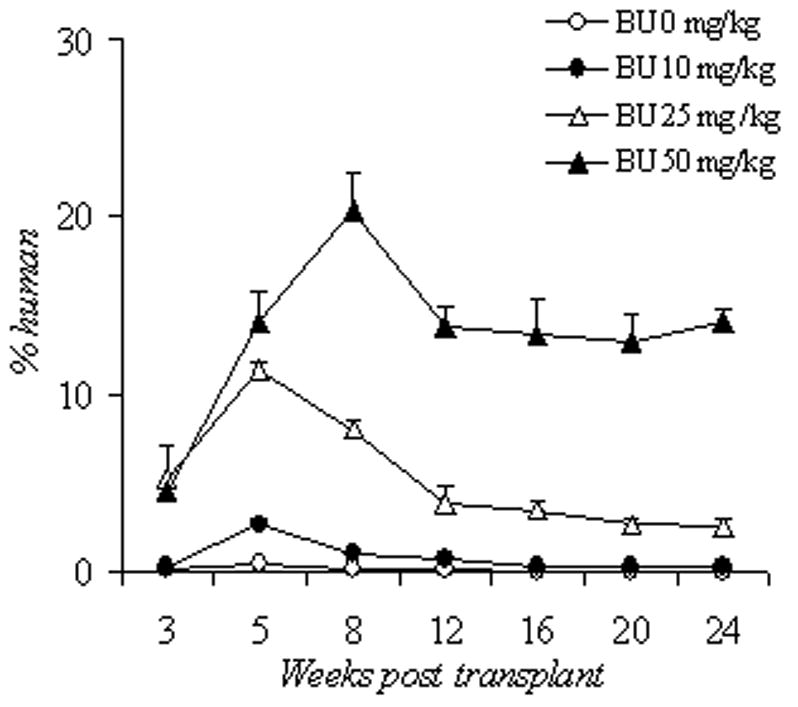

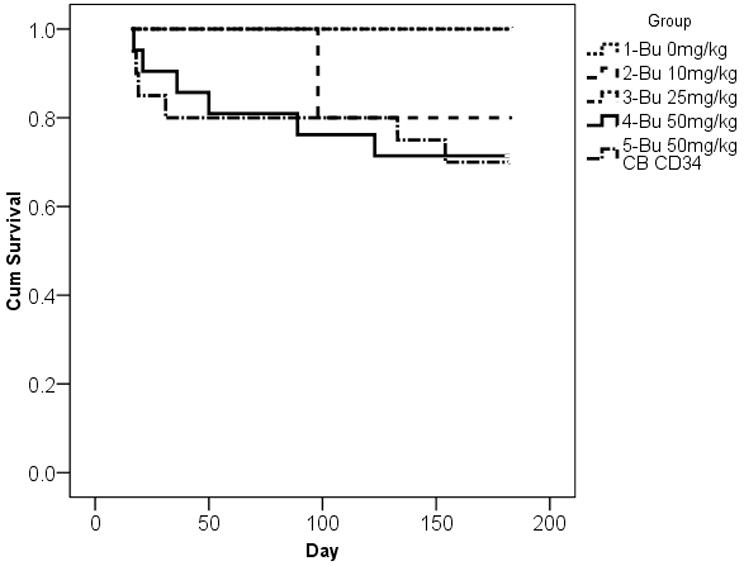

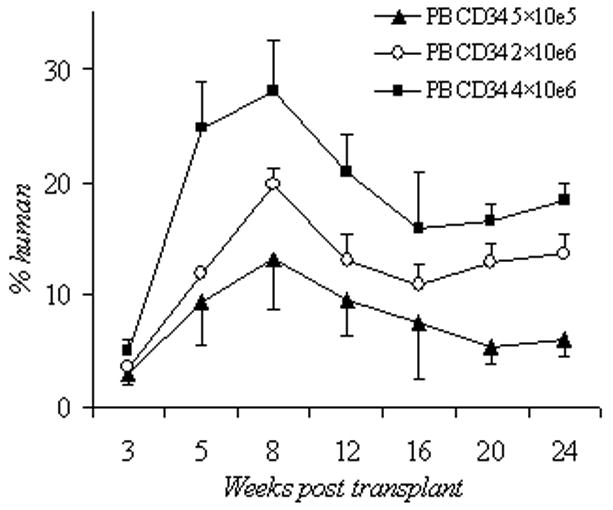

Survival and human cell engraftment after busulfan conditioning. (A): Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival after escalating doses of irradiation and xenotransplantation using human PB CD 34+ cells (2×10e6 cells per mouse). Group 1: 3 Gy (n=9), group 2: 2 Gy (n=8), group 3: 1.5 Gy (n=7), and group 4: 1Gy (n=10). (B): Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival after escalating doses of BU and xenotransplantation using human PB CD34+ cells (2×10e6 cells per mouse) or CB CD34+ cells (2 × 10e6 cells per mouse). Group 1: 0 mg/kg of BU (n=5), group 2: 10 mg/kg of BU (n=5), group 3: 25 mg/kg of BU (n=5); group 4: 50 mg/kg BU (n=20); group 5: 50 mg/kg of BU with 2x 10e6 CB CD34+ cells (n=21). Groups 1–4 were infused with PB CD34+ cells. (C): Human CD45+ cell engraftment following escalating doses of BU (0–50 mg/kg) using human PB CD34+ cells (2×10e6 cells per mouse); n=5 mice per cohort. (D): Human CD45+ cell engraftment after escalating doses of PB CD34+ cells following 50mg/kg BU; 5×10e5 PBCD34+ (n=7 mice); 2×10e6 PB CD34+ (n=6); 4×10e6 PB CD34+ (n=4). Bu, busulfan; CB, cord blood; Cum, cumulative; PB, peripheral blood.

NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice were then treated with escalating doses of busulfan from 10 to 50 mg/kg prior to infusion of 2×106 PB CD34+ cells. The mean percentage of human CD45+ cells detected at 24 weeks was 2.5% ± 0.5% in the 25mg/kg group and 14.1% ± 0.8% in the 50mg/kg group (Figure 1b). In surviving mice with follow-up up to 12 months, human cell engraftment remained persistent and stable (data not shown). Mortality estimates were more favorable after busulfan treatment and infusion of PB CD34+ (2 × 106 cells per mouse), with the majority of mice surviving long-term (Figure 1c).

We then sought to determine whether increasing PB CD34+ cell number could improve engraftment following 50mg/kg busulfan. The percentage of human CD45+ cells in the recipient mice rose in a dose-dependent manner: 6.1 ± 0.9% in the 5×105 group (n=4), 13.7 ± 2.5% in the 2×106 group (n=6), and 18.3 ± 1.6% in the 4×106 group (n=7). The p value for the comparison between the 5×105 and 2×106 groups was 0.03, and the p value between 2×106 and 4×106 groups was 0.156 (Figure 1d). With higher PB CD34+ or busulfan doses, the percent human chimerism appeared to be the highest at 8 weeks; it then decreased and plateaued at 20–24 weeks.

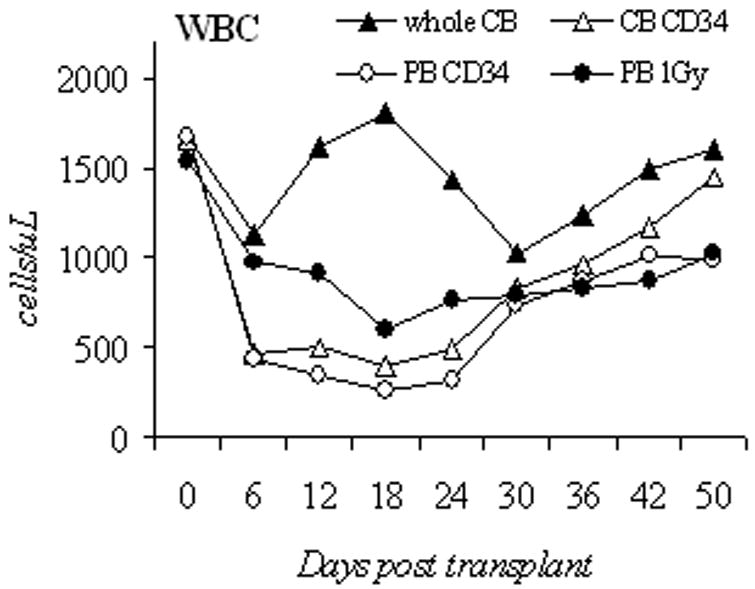

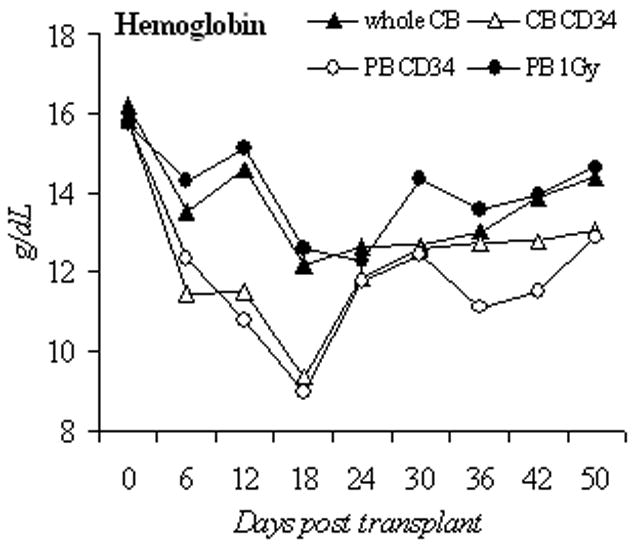

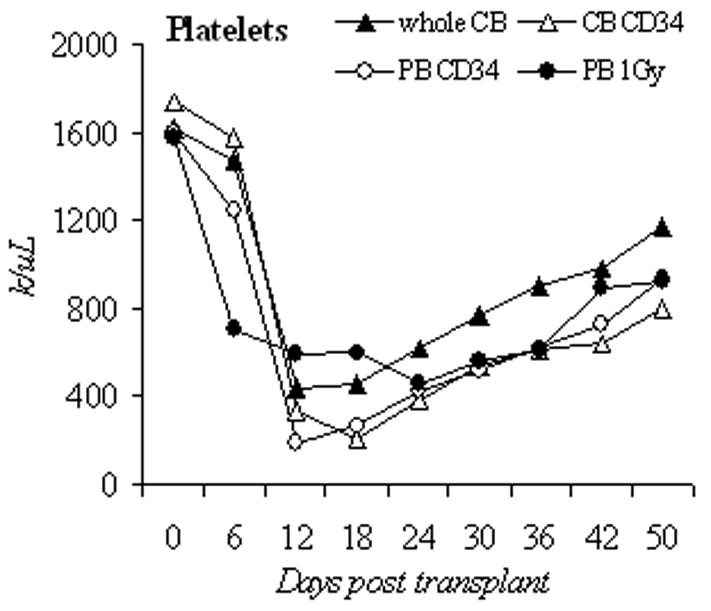

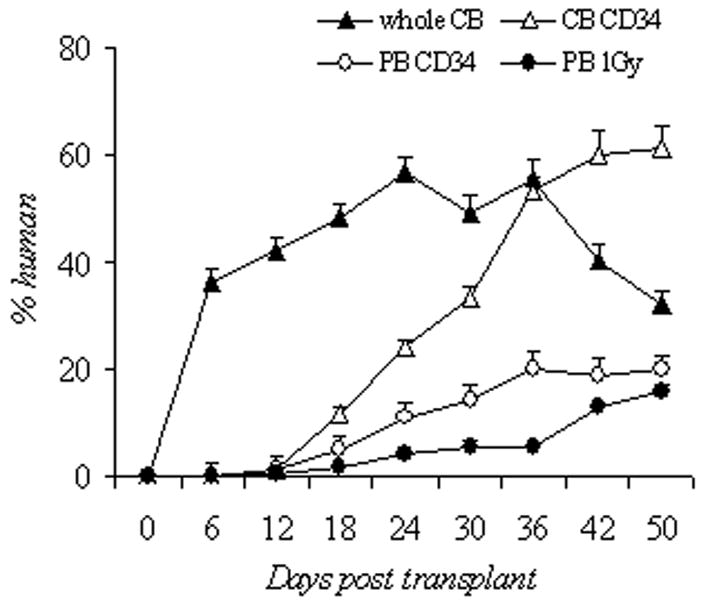

Unselected CB graft Contributed Mostly T cells Detectable as Early as 6 Days Post-Transplant

We then chose 50 mg/kg of busulfan to compare engraftment of PB CD34+, unselected cord blood mononuclear cells (unselected CB), and CD34+ selected cord blood cells (CB CD34+). The busulfan dose was lowered to 25 mg/kg in unselected CB group because in an initial experiment, all unselected CB recipient animals died from pancytopenia after 50mg/kg of busulfan (n=8, data not shown). To evaluate the depth and duration of busulfan effects on hematopoiesis in this 3rd generation NOD/SCID mouse and to allow comparison to previously published results, we monitored the blood count recovery pattern and human cell engraftment in the first 50 days after the transplantation in 4 groups: unselected CB with busulfan 25mg/kg (n=7), CB CD34+ with busulfan 50mg/kg (n=8), PB CD34+ with busulfan 50mg/kg (n=5) and PB CD34+ with 1Gy radiation (n=5). With the exception of the unselected CB group, the nadir counts for WBC, hemoglobin, and platelet in busulfan treated mice were near day 18, and approached baseline values by day 42 (Figures 2a, 2b, 2c).

Figure 2.

Blood counts and human cell engraftment after busulfan conditioning. (A–C): PB counts of NOD/SCID IL2Rγnull mice after busulfan conditioning and transplantation of human cells. Complete blood counts were determined from day 0 to day 50 post transplantation. Shown are unselected CB (1×108 cells, busulfan 25mg/kg, n=7 mice), CB CD34 (2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg, n=8), PB CD34 (2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg, n=5), and 1Gy PB (2×106 cells, 1Gy, n=5). (D): Percentage of circulating human CD45+ cells in the early engraftment period. PB was analyzed for the percentage of cells of human origin by flow cytometry for CD45 positivity from day 0 to day 50 post transplantation. Shown are unselected CB (1×108 cells, busulfan 25mg/kg, n=7 mice), CB CD34 (2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg, n=8), PB CD34 (2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg, n=5), and PB 1Gy (2×106 cells, 1Gy, n=5). CB, cord blood; PB, peripheral blood; unsel, unselected; WBC, white blood cell.

We then assessed the percentage of human CD45+ cells in these mice during the same early engraftment period (Figure 2d). In these recipients, 36±2.4% human cells were detected as early as day 6 in the unselected CB mice, and remained higher (42.3 to 56.7%) than the other 3 groups (1.8–33.5%) for the first 30 days. The unselected CB grafts contain mature leukocytes, namely CD3+ cells. After infusion, this likely led to the observed higher percentages of human cells from days 6 to 30 (Figure 2a). In the other 3 groups, human cells were not detected until day 18. Additionally, cord blood grafts consistently led to higher percentages of human CD45+ cells detected, CB CD34+ group (61.2±4.0%, n = 8) vs. PB CD34+ group (19.9±1.5%, n=5, p<0.001).

CD34+ selected CB cells gave rise to all human white cell subsets at 8 weeks post transplant

Since infusion of unselected CB cells resulted in the highest percentage of engraftment in the first 4 weeks, we sought to determine to what extend human cell “engraftment” represents mature blood elements from the graft assayed in the circulation and further, how long such mature elements persist. Three groups of mice were compared: 25 mg/kg busulfan and 1×108 unselected CB cells, 50 mg/kg busulfan and 2×106 CB CD34+ cells, and 50 mg/kg busulfan and 1×107 CB CD3+ cells. At day 6, the average percentage of human cells were 27.3±2.7% in unselected CB group, 0.17±0.04% in CB CD34+ group, and 6.51±2.1% in CB CD3+ group. One representative mouse from unselected CB and CB CD34+ groups was sacrificed, and the percentages of human cells at day 6 in the spleen and bone marrow were: unselected CB 45.1% and 1.1%; CB CD34+, 0.1% and 0%, respectively. These results confirmed that during the first week post transplant, most of the circulating human leukocytes and splenocytes were T cells from the infused unselected CB cells. At week 3, the average percentage of human cells in peripheral blood was 49.7±2.4% in unselected CB, 25.9±1.7% in CB CD34+, and 8.8±2.3% in CB CD3+.

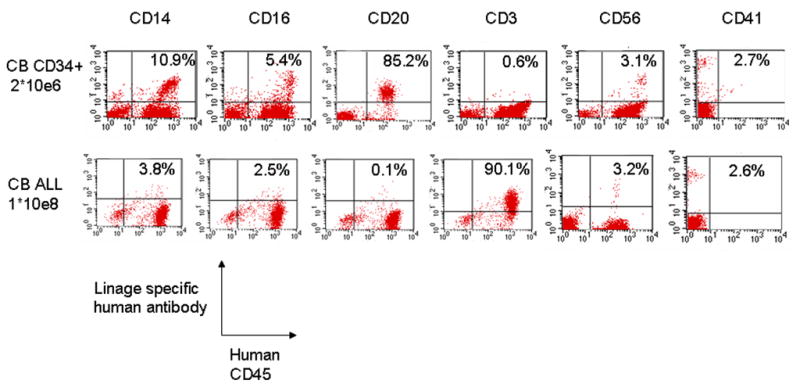

We then compared transplant outcome in various leukocyte lineages in unselected CB and CB CD34+ mice at 8 weeks. A representative flow panel (Figure 3) showed that CB CD34+ mice have higher percentage of human myeloid (CD14, CD16) and B (CD20) cells, lower T (CD 3) cells, and similar NK (CD56) and platelet progenitor (CD41) cells, compared to unselected CB mice. The B cells stained positively for human IgM or IgG, and the T cells stained positively for CD4 or CD8. When BM and spleen cells were assayed, the white cell subsets were similar to the observed percentages in peripheral blood (data not shown). This pattern of delayed CD3 engraftment was also seen in mice that received PB CD34+ cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Representative flow cytometry panels of leukocyte subsets of one chimeric NOD/SCID IL2Rγnull mouse at 8 weeks post transplantation. Unselected CB (CB ALL, 1×108 cells, busulfan 25mg/kg); CB CD34+ (2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg)

CD34+ Selected CB Grafts Produced Superior Long-Term Engraftment

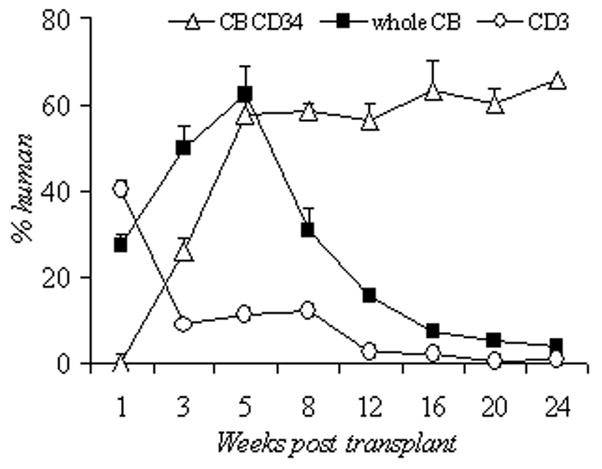

To assess the long-term (>8 weeks) contribution of human cell from the different cell sources, another set of mice were transplanted with comparable cell numbers of CB CD34+ cells (2×106, n=7), unselected CB (1×108, n=6), and CB CD3+ cells (2×107, n=3) after busulfan conditioning (Figure 4). The CB CD34+ group had an average of 25.9% human cells at 3 weeks, which increased to and sustained between 60–65% at 24 weeks post-transplant. Unselected CB group had the highest initial human chimerism (49.7%, similar to Figure 2d), reached 62.5% at 5 weeks, decreased to 30.2% at 8 weeks, and decreased to 4.27% at 24 weeks. The CB CD3+ group had the lowest human chimerism throughout the entire monitoring period yet showed moderate levels early post-infusion.

Figure 4.

Percentage of circulating human CD45+ cells up to 24 weeks post transplant using 3 cord blood compositions. CD34+ selected cord blood (CB CD34, 2×106 cells, busulfan 50mg/kg, n=7), unselected cord blood (unsel CB, 1×108 cells, busulfan 25mg/kg, n=6), CD3 selected cord blood (CD3, 2×107 cells, busulfan 25mg/kg, n=3). CB, cord blood.

After 6 months of follow-up, the recipient’s BM (1×108 cells) from CB CD34+ mice were harvested and transplanted to secondary NOD/SCID IL2Rγnull recipients conditioned with same busulfan dose (50mg/kg). Human CD45+ cells of multiple leukocyte lineages were detected at 4.93±1.7% (n=3) in both groups up to 24 weeks (data not shown). These results showed that both PB and CB CD34+ cell sources contributed long term HSCs in this xenograft transplantation model.

Erythroid Colony Maturation Was Detectable In Vitro after Plating Marrow of Recipient Mice in Human Cytokines with Human Tf

Although human derived leukocyte and megakaryocytic cells are detected in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull peripheral blood, no human red blood cells were detectable throughout the entire monitoring period, regardless of the type of donor human cells infused. To ensure the human HSCs in the humanized mice have a capability to differentiate into erythroid cells in vitro, BM was harvested from recipient mice at 2 days, 7 days, 2 months, and 6 months after transplants in the CB CD34+ group. At 6 months post-transplant, 1×105 BM cells were inoculated in semisolid methylcellulose media supplemented with human cytokines and Tf; colonies were counted and shown in Table 1. PCR for human ALU sequences was positive for colonies grown in human specific media (data not shown).

Table 1.

Chimeric bone marrow cells (1×105) were plated in semisolid media. Colonies were counted after 14 days of incubation.

| Myeloid | Erythroid | Mixed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human cytokines, no human transferrin | 30 ± 1 | 0 | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| Human cytokines + human transferrin | 95 ± 3 | 64 ± 3.4 | 7.6 ± 0.7 |

| Murine cytokines | 90 ± 7.6 | 72 ± 3 | 16.3 ± 3 |

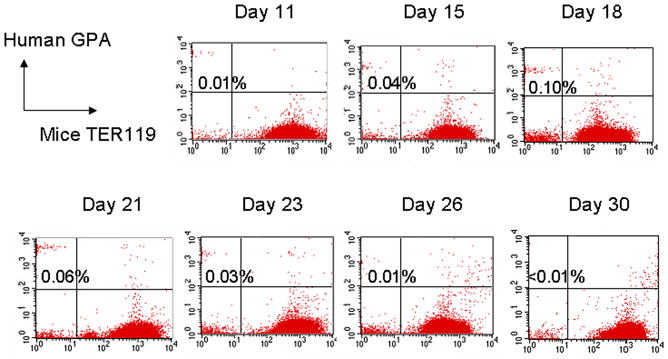

Human Red Blood Cells Are Detectable In Vivo after Treatment with Human Tf

We then sought to determine whether RBC output is limited by the absence of human growth factors. We transplanted additional mice with CB CD34+ cells, and treated them with five different human cytokine cocktails to mimic in vitro culture conditions: 1) Tf alone; 2) Tf and CFU cytokines; 3) Tf, CFU cytokines, and anti-CD122; 4) Tf and erythroid culture cytokines; and 5) Tf, erythroid culture cytokines, and anti-CD122. Human red cells were detectable in all five groups, but only from days 11 through 30 post transplant, with a maximum of up to 0.1% at day 18 (Figure 5). Human cytokines or anti-CD122 antibody did not increase the percent of human RBCs over Tf alone. These results suggested that human Tf played a crucial role to support human erythropoiesis in the chimeric mice. To confirm that the GPA+ cells were of human origin, GPA+ RBCs from day 18 were sorted and lysed, and the hemoglobin extracts were analyzed by tandem HPLC-mass spectroscopy (MS). MS revealed the presence of human α- and β-globin chains.

Figure 5.

Representative flow panel of human GPA+ red cells in peripheral blood of chimeric NOD/SCID IL2Rγnull mouse from day 5 to 35. Mice received 50mg/kg busulfan, 2×106 CB CD34+ cells, and human Tf 3 times a week for 3 weeks. GPA, glycophorin A

We then assayed the bone marrow and spleen to determine whether erythroid progenitors can be detected at the time when circulating human RBCs are present. In the bone marrow, 5.96% of the cells were GPA+, and 5.81% were doubly positive for human CD45 and CD71. When Tf injections were administered later at 60, 120, 150, and 180 days post transplant, BM erythroid progenitors decreased substantially (Table 2, with some data not shown), suggesting that late Tf administration cannot rescue erythroid progenitors, and that there might be overwhelming signals in the chimeric bone marrow inhibiting human erythropoiesis.

Table 2.

Percent human erythroid cells

| PB * | BM GPA+ ** | BM CD71+ ** | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tf + human cytokines began at day 0 | 0.029 +/− 0.01% | 5.96 +/− 0.31% | 5.81 +/− 1.94% | 3 mice |

| Tf began at day 120 | 0% | 0.2 +/− 0.16% | 1.69 +/− 1.1% | 3 mice |

| No Tf | 0% | 0% | 0% | 6 mice |

Peripheral blood (PB) assayed at 18 days after treatment of human cytokines.

Bone marrow (BM) cells assayed at 21–28 days after last day of cytokine treatment.

GPA, glycophorin A; Tf, transferrin.

Human Red Cells Are Quickly Cleared after Transfusion in Mice

Next, to confirm if the NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice can tolerate human red cells, mice were injected with 750uL of type O and Rh-negative human RBCs, which should increase human red cell to 10%–20% in mice. The actual percentage of human RBCs in peripheral blood was only 2–3% at 2 hours, 1–1.5% at 72 hours, and 0% at 1 week. Pretreatment with busulfan, anti-CD122, or splenectomy did not prolong the survival of circulating human RBCs in mice. Serum levels of total bilirubin were elevated in the mice 72 hours after the infusion (2.13±0.29 mg/dl vs. 0.267±0.03mg/dl; n=3; p<0.01). Other blood types were infused, O-positive and A-positive, and similar results were obtained (data not shown). These results indicated that human HSCs in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice can be cultured to grow human RBC ex vivo, transfused human RBCs can transiently persist in vivo, and human RBCs were cleared, at least in part, by extravascular hemolysis.

Discussion

We have previously shown that low-dose busulfan alone provides dose dependent engraftment in congenic normal C57BL6 mice12 and is sufficient preconditioning for gene therapy applications in the rhesus macaque model22, 23. We sought to develop a practical, humanized mouse model that allows reliable, high-level human cell engraftment to reduce the need for the more cumbersome and expensive nonhuman primate model. Here we report busulfan as a desirable alternative conditioning agent in the NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice. Busulfan at the doses of 25–50mg/kg yielded 15%–20% human chimerism from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cell sources, and 60%–70% human chimerism from CB CD34+ cell sources. This high level of human chimerism was achieved after busulfan conditioning with low mortality rates. Additionally, ease of administration and the lack of the more cumbersome administrative oversight required of an irradiation source make this a desirable conditioning agent for human HSC xenografting. The dose of 50mg/kg may be approaching the lethal dose for these mice as none of the recipients of 1 × 108 unselected CB cells at this busulfan dose survived the early post-transplant period, though this mortality was not seen with other cell sources. Interestingly, high-level chimerism in excess of 90% was seen in these mice, raising the possibility that such high levels of human chimerism are detrimental in this setting. Blood counts after busulfan dosing decreased precipitously during the first week, nadired in the second to third week, and began to recover at the fourth week. This pattern of hematologic toxicity is similar to that reported in congenic mouse models, monkeys, and humans12, 23.

Our transplantation studies with CB CD34+ selected cells in 8–10-week-old recipients resulted in significant levels of human chimerism at 60%–65%. These percentages are similar to the observed 73% in newborn NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull after 100 cGy9, 30%–40% in 8–12-week-old mice after 240 cGy8,24; yet significantly higher than the 5–10% observed in mice of similar aged (8–10 week old) after 300 cGy25. Our higher cell dose may in part explain our better results, and further supports a dose-dependent engraftment in this xenograft model. The lower percentage of human cells following a PB stem cell source in our study has also been observed previously using 7×105 PB CD34+ cells after 325 cGy of irradiation6. These results are in agreement with previous studies showing that CB CD34+ cells have higher engrafting potential than PB CD34+ cells.

Regardless of the source, engrafted human HSCs differentiated into all leukocyte lineages in PB, BM, and spleen. The unselected CB group showed a 90% human T-cell chimerism at 8 weeks, which resulted predominantly from the mature T-cells in the infused graft. As these mature human T cells senesced, the percentage of human chimerism decreased sharply. In contrast, the CB CD34+ group achieved 85% human B-cell chimerism at 8 weeks, and the T-cell engraftment was lower and gradual. The average time to reach maximal human total leukocyte chimerism depended on the cell dose: 5 weeks in our study with 2 × 106 CB CD34+ cells and 20 weeks with 5 × 104 cells8, 24 (figure 4). These engraftment kinetics suggest that inferring human HSC activity at early timepoints (ie before 12 weeks post-transplant) may be misleading. Our observations from the infusion of CD3 selected CB cells strengthens this point, showing that mature elements may persist in this model for some time post infusion.

Ishikawa et al previously showed that 3 months after transplant in newborn mice, a small (unquantified) percent of human red cells were in peripheral circulation and 9.5% human erythroid progenitors were present in the bone marrow9. When bone marrow cells were cultured by CFU, there were few pure red cell colonies, and white cell colonies dominated. Mazurier et al detected human glycophorin A positive cells in xenograft recipients in the bone marrow and peripheral blood beginning 2 weeks after direct intrafemoral injection, but the human erythrocytes decreased to 5% or less at 6 weeks26. Our study utilized busulfan and adult mice, and human erythroid colonies could be grown using human cytokines from 2 days to 6 months after transplant. However, we observed only 0.1% percent human red cells in recipient peripheral blood on day 18 after transplant, and 6% GPA+ cells in the bone marrow. These collective observations indicate that the bone marrow often contains much higher human erythroid content than the peripheral blood compartment. Furthermore, we observed human RBCs only with the use of human holo- or apo-Tf, suggesting that the human iron transport protein is important in erythropoiesis in this chimeric model. Tf is a glycoprotein with an approximate molecular mass of 76500 kD, produced in liver, and it binds and transports iron to the bone marrow 27. There is only 78.05% nucleic acid and 74.1% amino acid homology between human and murine Tf using the HomoloGene database.

The presence of human erythroid progenitors in BM and much lower readout of mature human RBC in circulation suggest there may be an inhibitory cytokine milieu suppressing human erythropoiesis. This can be inferred from Hexner et al, where adding ex vivo expanded CD3/CD28 co-stimulated CB T cells, in addition to CB CD34+ cells, increased GPA+ cells in the bone marrow from average of 9.3% to 36.4%25. When we administered Tf at 2 or 6 months post transplant, ≤0.01% human RBCs could be detected, suggesting that late Tf and human cytokines administration cannot rescue erythroid progenitors, and that there might be overwhelming inhibitory signals of human erythropoiesis in the chimeric bone marrow.

When we infused mature cross-matched human RBC in transplanted mice, only 1–3% (compared to the calculated 10%) of recipient blood was human. These human RBCs circulated for up to 3 days; their disappearance corresponded with an increase in serum total bilirubin. The anti-CD122 antibody directs against the IL-2Rβ chain and targets NK cells and macrophages28. Murine NK cells were previously shown to prevent engraftment of human cells in other NOD/SCID strains 29, 30. We employed this antibody as a strategy to deplete functional macrophages post transplant and minimize erythrophagocytosis in the bone marrow or spleen. However, the addition of anti CD122 antibody or pretreating the mice with splenectomy did not prolong the lifespan of human red cells. These results are consistent with those of Fujimi et al31 and suggest the liver is the major organ of RBC sequestration and extravascular hemolysis further contributes to the lack of human red cells. Taken together, several reasons explain why human RBCs are detectable at only low levels in these NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice despite leukocyte engraftment that is robust: inhibitory cytokines or bone marrow environment that suppress human erythropoiesis, lack of specific human erythroid growth factors, peripheral clearance, and sequestration.

Summary

Our results demonstrate that busulfan preconditioning is sufficient to produce stable and high level engraftment of human cells in NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull mice. CD34+ selected cord blood grafts provide superior engrafting potential when compared to mobilized peripheral blood stem cells from healthy adults. Importantly, this high level engraftment can be achieved with low mortality, substantially reducing the number of animals required for experiments requiring long-term follow-up. Finally, supplementation with human Tf allows the detection human erythrocytes in this chimeric mouse assay, providing a potential model for the study of disorders affecting human red blood cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK and NHLBI at the NIH. We thank Elizabeth Joyal for collection of the cord blood samples, Martha Kirby for cell sorting, and D Eric Anderson for mass spectroscopy.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There is no significant financial conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions: Jun Hayakawa: Conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing.

Matthew M. Hsieh: Conception and design, administrative support, manuscript writing, data analysis and interpretation.

Naoya Uchida: Data analysis and interpretation.

Oswald Phang: Collection and assembly of data.

Tisdale F. John: Conception and design, financial support, administrative support, final approval of manuscript.

References

- 1.Yoshino H, Ueda T, Kawahata M, et al. Natural killer cell depletion by anti-asialo GM1 antiserum treatment enhances human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment in NOD/Shi-scid mice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueda T, Tsuji K, Yoshino H, et al. Expansion of human NOD/SCID-repopulating cells by stem cell factor, Flk2/Flt3 ligand, thrombopoietin, IL-6, and soluble IL-6 receptor. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1013–1021. doi: 10.1172/JCI8583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueda T, Yoshino H, Kobayashi K, et al. Hematopoietic repopulating ability of cord blood CD34(+) cells in NOD/Shi-scid mice. Stem Cells. 2000;18:204–213. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-3-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollet O, Peled A, Byk T, et al. beta2 microglobulin-deficient (B2m(null)) NOD/SCID mice are excellent recipients for studying human stem cell function. Blood. 2000;95:3102–3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glimm H, Eisterer W, Lee K, et al. Previously undetected human hematopoietic cell populations with short-term repopulating activity selectively engraft NOD/SCID-beta2 microglobulin-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:199–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yahata T, Ando K, Nakamura Y, et al. Functional human T lymphocyte development from cord blood CD34+ cells in nonobese diabetic/Shi-scid, IL-2 receptor gamma null mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:204–209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiramatsu H, Nishikomori R, Heike T, et al. Complete reconstitution of human lymphocytes from cord blood CD34+ cells using the NOD/SCID/gammacnull mice model. Blood. 2003;102:873–880. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa F, Yasukawa M, Lyons B, et al. Development of functional human blood and immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2 receptor {gamma} chain(null) mice. Blood. 2005;106:1565–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauch P, Down JD, Warhol M, et al. Recipient preparation for bone marrow transplantation. I. Efficacy of total-body irradiation and busulfan. Transplantation. 1988;46:205–210. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Down JD, Ploemacher RE. Transient and permanent engraftment potential of murine hematopoietic stem cell subsets: differential effects of host conditioning with gamma radiation and cytotoxic drugs. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:913–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh MM, Langemeijer S, Wynter A, et al. Low-dose parenteral busulfan provides an extended window for the infusion of hematopoietic stem cells in murine hosts. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:1415–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santos GW. Preparative regimens: chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy. A historical perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;770:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamiguchi H, Wingard JR, Laver JH, et al. An assay for human hematopoietic stem cells based on transplantation into nonobese diabetic recombination activating gene-null perforin-null mice. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa F, Livingston AG, Wingard JR, et al. An assay for long-term engrafting human hematopoietic cells based on newborn NOD/SCID/beta2-microglobulin(null) mice. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:488–494. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert-Richard E, Ged C, Ortet J, et al. Human cell engraftment after busulfan or irradiation conditioning of NOD/SCID mice. Haematologica. 2006;91:1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenzie JL, Gan OI, Doedens M, et al. Human short-term repopulating stem cells are efficiently detected following intrafemoral transplantation into NOD/SCID recipients depleted of CD122+ cells. Blood. 2005;106:1259–1261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang EM, Areman EM, David-Ocampo V, et al. Mobilization, collection, and processing of peripheral blood stem cells in individuals with sickle cell trait. Blood. 2002;99:850–855. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayakawa J, Migita M, Ueda T, et al. Generation of a chimeric mouse reconstituted with green fluorescent protein-positive bone marrow cells: a useful model for studying the behavior of bone marrow cells in regeneration in vivo. Int J Hematol. 2003;77:456–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02986613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell JD, Fitzhugh C, Kang EM, et al. Low-dose radiation plus rapamycin promotes long-term bone marrow chimerism. Transplantation. 2005;80:1541–1545. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000185299.72295.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tisdale JF, Hanazono Y, Sellers SE, et al. Ex vivo expansion of genetically marked rhesus peripheral blood progenitor cells results in diminished long-term repopulating ability. Blood. 1998;92:1131–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuramoto K, Follman D, Hematti P, et al. The impact of low-dose busulfan on clonal dynamics in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2004;104:1273–1280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang EM, Hsieh MM, Metzger M, et al. Busulfan pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and low-dose conditioning for autologous transplantation of genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells in the rhesus macaque model. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, et al. NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood. 2002;100:3175–3182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hexner EO, Danet-Desnoyers GA, Zhang Y, et al. Umbilical cord blood xenografts in immunodeficient mice reveal that T cells enhance hematopoietic engraftment beyond overcoming immune barriers by stimulating stem cell differentiation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazurier F, Doedens M, Gan OI, et al. Rapid myeloerythroid repopulation after intrafemoral transplantation of NOD-SCID mice reveals a new class of human stem cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nm886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews NC. Iron homeostasis: insights from genetics and animal models. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:208–217. doi: 10.1038/35042073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shultz LD, Banuelos SJ, Leif J, et al. Regulation of human short-term repopulating cell (STRC) engraftment in NOD/SCID mice by host CD122+ cells. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzue K, Reinherz EL, Koyasu S. Critical role of NK but not NKT cells in acute rejection of parental bone marrow cells in F1 hybrid mice. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3147–3152. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3147::aid-immu3147>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Rezzoug F, Chilton PM, et al. Matching at the MHC class I K locus is essential for long-term engraftment of purified hematopoietic stem cells: a role for host NK cells in regulating HSC engraftment. Blood. 2004;104:873–880. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimi A, Matsunaga T, Kobune M, et al. Ex vivo large-scale generation of human red blood cells from cord blood CD34(+) cells by co-culturing with macrophages. Int J Hematol. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]