NEW HEADING: "FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK".

Items will appear from time to time under this new heading to address topics chosen by our scientific editorial department. They will be concerned either with concrete aspects of the scientific articles appearing in Deutsches Ärzteblatt (e.g., conflicts of interest or the evaluation of the CME units) or with general questions of medical publishing, as in the current article.

Medicine uses one lingua franca but speaks with many tongues. Just as Latin emerged after the Renaissance beside the regional European languages as the unifying language of the healing arts, so has English now assumed a leading role as the international language of medicine. International communication among clinicians and scientists is now almost exclusively in English. Nonetheless, patient contact, communication among colleagues within individual countries, teaching, and some scientific activity are still conducted in the local mother tongues.

As late as the beginning of the 20th century, medical science still used three languages to a roughly equal extent: German, English, and French. The turn to English, which took place at different speeds in different areas since the middle of the last century, has put an end to linguistic confusion and is thus to be welcomed, from a worldwide perspective, as a positive instance of globalization. There are, nonetheless, some negative consequences for scientific culture outside the English-speaking world. This article will deal with the extent of the secular trend toward English and its consequences for scientific readers, writers, and journals.

The anglicization of medicine

The following three examples will concretely illustrate the degree to which international medical publishing has become anglicized:

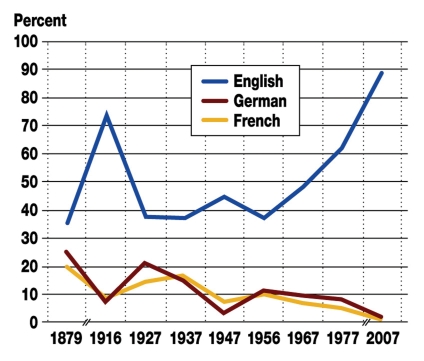

In the last 130 years, the percentage of English-language journals in the American journal catalog Index Medicus/Medline has risen from 35% to 89%; the percentage of German-language journals in Index Medicus/Medline, on the other hand, has decreased from almost 25% to 1.9% ([1], data obtained by the author). In 1879, 284 journals in the Index Medicus were published in English and 201 in German. Last year, Medline, an online journal database that grew out of the Index Medicus, listed only 98 journals in German, a number that pales in comparison to 4609 in English. Like the German language, French, too, has become far less important on an international level (figure 1). Roughly 9 of every 10 new journals included in Medline at present are in English.

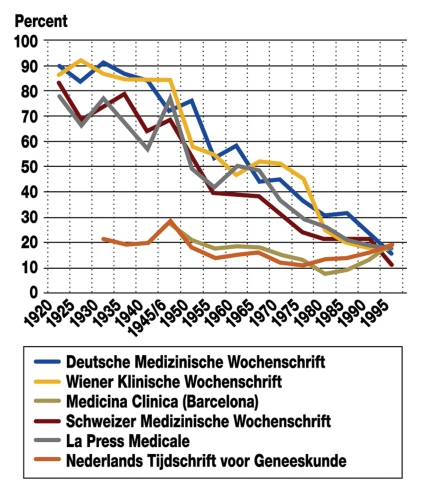

Navarro analyzed the lists of references for articles published in three major German-language medical weeklies (the Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (DMW), the Schweizer Medizinische Wochenschrift, and the Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift) and found that the percentage of references in German declined from 80% to 90% in 1920 to 10% to 20% in 1995 (figure 2) (2–4). He obtained comparable results for journals in French, Dutch, and Spanish (5–7). In journals in all of these languages, English-language articles accounted for 80% to 90% of the references. This trend continues today: in 2007, 80% of the references of scientific articles in Deutsches Ärzteblatt were in English.

The dominance of English among leading scientific journals is even more overwhelming. The Journal Citation Report lists the journals that are most frequently cited (those with the highest impact factor, IF), i.e., the journals that are most highly respected around the world. Among major medical journals in the category "Medicine, General & Internal," the highest-ranking publication in a language other than English is Medicina Clinica (Barcelona), in 44th place on the list. Of the 103 journals that are listed in this category, only 13 are not written (entirely or primarily) in English, and only three of this small group are in German: DMW, Medizinische Klinik, and Der Internist. The impact factors of these 13 journals added together yield 5.2 – less than the impact factor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal, which reaches 9th place with a score of 6.9. The most commonly cited journal is the New England Journal of Medicine, whose impact factor, 51.3, is almost 100 times as high as that of the DMW (0.58), the highest-ranking German-language journal in the category. These findings apply to other areas of medicine as well, as shown, e.g., for gynecology by Lenhard et al. (8). As the impact factor of a journal is derived from the number of times its articles are cited by other journals around the world, it follows that a journal can only have a high impact factor if it is well understood internationally. Therefore, English-language journals have a built-in advantage.

Figure 1.

The representation of German-, French-, and English-language journals in the Index Medicus and Medline, 1879–2007 (from [1] and data obtained by the author)

Lippert [1] determined the languages of the journals from their titles. The number of German-language journals prior to 1977 is, therefore, somewhat higher than documented, because some of the journals with Latin titles (11% of the 2265 journals listed in the Index Medicus in 1967) were actually written in German. Absolute numbers for 1879: among 810 journals in the Index Medicus, 284 were in English, 201 in German, and 160 in French. Absolute numbers for 2007: among 5204 journals in Medline, 4609 (88.6%) were in English, 98 (1.9%) in German, and 81 (1.6%) in French.

Figure 2.

The percentage of references in the mother tongue in six international medical journals (2–7)

Method: Navarro counted the references in 50 original articles in each journal at 5-year intervals (2–7).

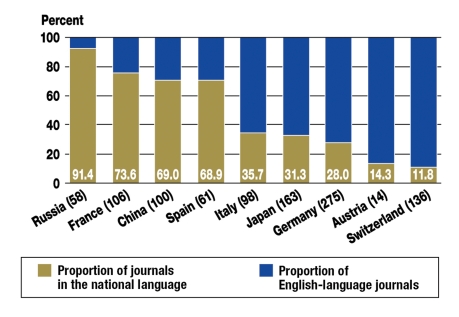

The trend toward English is unequivocal, but the scientific cultures of different countries have yielded to it to varying extents. This can be seen from the variable percentages of references in the home language that were found by Navarro: in 1995, for example, 20% of the references in the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde were in Dutch, while only 11% of the references in the Schweizer Medizinische Wochenschrift were in German (3, 6). A look at the journals published in various countries that are listed in Medline reveals that the number of journals published in English is lower, in both an absolute and a relative sense, in France and Russia (to give two examples) than in Switzerland or Germany (figure 3).

Figure 3.

The percentage of references in the national language among all journals listed in Medline published in nine different countries

The site of publication was determined from the entry under "Country" in the Medline Journals Database (e.g., "Country: Germany"), while the language of publication was determined from the entry under "Language." The numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of journals listed in Medline that were published in each country as of October 2007.

Tendencies in the other direction

There is, nonetheless, a discernible regional movement counterbalancing the trend toward English in international scientific publishing: more and more journals are appearing in languages other than English, so that the percentage of all scientific periodicals worldwide that are published in English is declining (personal communication from Mohammad Hossein Biglu, Institute for Library and Information Science [IBI], Humboldt University, Berlin, November 2007). This has come about because scientific cultures are now developing in many countries, such as China and Brazil, and thus an increasing number of journals are coming out in the national languages for use by the medical public in each country. Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, which is probably the most comprehensive bibliographical database for journals, lists 22 257 current medical journals for the year 2007, of which almost 10 000 can be considered scholarly or academic; 3000 of these are in languages other than English. This count is probably too low, as it might well be that some journals in national languages were not included in the directory.

On the Internet as well, it can be seen that, as scientific cultures develop in non-English-speaking countries, the dominance of English is less than it was. The British author David Graddol, noting the growing use of the Internet outside the English-speaking world, has written (9): "The dominance of English on the Internet is declining. Other languages, including lesser-used languages, are now proliferating."

A strong tradition in the mother tongue is also still alive in Germany today. Thus, German-language journals make up almost one-fifth of all periodicals to which the German National Library of Medicine (Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für Medizin, ZBMED) subscribes. Out of more than 6800 current specialized periodicals, the ZBMED reports that it holds no fewer than 1550 titles in German, of which 1236 (18.1%) can be considered journals in the strict sense. Thus, there are at least 1100 medical journals in German that are not indexed by Medline.

This enormous number is already an indirect indication of the high demand for German-language reading matter in the German-speaking countries. Doctors also tell us directly about this need: in a poll of more than 300 physicians in private practice regarding the use of the Internet for continuing medical education, 7 out of 10 said it was important, or very important, that the articles they read should be in German (personal communication from Martin Härter, Department of Psychiatry, University of Freiburg, December 2007). The sales figures for English-language journals point in this direction, too: for example, the British Medical Journal, one of the best clinically oriented journals worldwide, had only 164 individual subscribers in Germany, a vanishingly low number among the roughly 390 000 physicians in the country (Geetha Balasubramaniam, British Medical Journal, December 2007; the figure does not include institutional subscribers, such as libraries).

The center and the periphery of medical science

There are thus two trends in international medical publishing. A central core of English-language journals has formed that contains the most important medical journals worldwide and is the forum for scientific debate on important questions of current research. This central core is surrounded by a periphery containing a multitude of journals in national languages. These journals are mainly devoted either to continuing medical education or to branches of medical science that are rooted in the local culture, e.g., research on the delivery of care within the local national health system. The existence of this periphery gives the lie to the assertion that medicine has become a purely English-speaking field.

Consequences

The trend toward English as the most important language of medicine has consequences for German-language readers, authors, and journals. As early as the 1990’s, Egger et al. showed that German scientists mainly publish their positive results in English-language journals, while tending to publish statistically insignificant findings in German-language journals (10). This observation seems to be generally true of scientific publishing in all languages other than English and underlies the recognized phenomenon of "language bias": review articles and meta-analyses based predominantly or exclusively on the English-language literature may be biased toward positive results for this reason alone.

In the few years that have gone by since the study of Egger et al., the tendency to publish important findings in English has grown even more pronounced: Galandi and colleagues from the German Cochrane Center found, in a study of eight German-language journals from 1948 to 2004, that no randomized, controlled trials (RCT’s) are being published in German any more, even though as many as 11 RCT’s were published per journal and per year in the 1970’s and early 1980’s (11). Schmucker et al. report a similar shift in the field of ophthalmology (12). The reason for this trend is to be found in the increasing importance of impact factors for the evaluation of academic performance, and thus for the scientists’ careers. Only English-language journals achieve high impact factors, because journals in other languages are unlikely to be read and cited internationally.

The need to publish in English probably puts many authors whose native language is not English at a disadvantage compared to their English-speaking counterparts, though this disadvantage may be difficult to quantify in figures. It is certainly the case that most authors in this country can express themselves more easily in German than in English. It follows that scientific work originating here will often be of a lower linguistic quality (the problem is surely more acute in some fields than others, e.g., in social medicine rather than biochemistry). For many scientists and physicians, medicine in English is a rather trying "away game." More than a few of them may well have difficulty reading articles in English, missing more of the subtleties of the text than they would if it were presented in German. Thus, the relinquishment of German as a scientific language carries the risk of a deterioration of content (13). Within the limited scope of this article, we can merely mention the often debated question whether certain languages might or might not be linked to certain styles of thought. If so, then the marginalization of a language or of entire groups of languages might lead to a change in the content of science (14–16).

For many German-speakers, "frictional losses" are inevitable when they read and write in English. Yet another effect of anglicization is that many of the leading German scientists – for the reasons discussed above – no longer write in German, not even in review articles, or else they do so only rarely. Many physicians, however, lack access to the English-language journals that constitute the core of medical science. As a result, the new medical knowledge gets across to the German-speaking medical public more slowly than would otherwise be the case. One cannot blame German-speaking authors for this situation, as their academic performance is evaluated almost exclusively on the basis of impact factors and citations, and they thus have no incentive to publish in German-language journals. Nonetheless, perhaps the research bureaucracy here ought to consider whether its evaluation methods are not, in fact, impeding the transfer of scientific knowledge to German-speaking society – while, at the same time, it is this society itself that supplies the funding for the medical research done in German-speaking lands.

In this context, we can also mention the debate over the supposed unfairness of Medline toward journals in languages other than English. This reproach is baseless, as it is clear that a database financed by American taxpayers would preferentially list journals that American physicians and scientists can read. It would, however, be a worthwhile project for the European Union’s research arm to develop a multilingual database of its own in which European periodicals were better represented.

The "Medicine" section of Deutsches Ärzteblatt: bilingual from now on

Many German-language journals have responded to the trend toward anglicization by switching their language of publication to English. Three specialized journals with long traditions in the German language can be mentioned as examples: the Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten is now called the European Archives for Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, the Zeitschrift für Kardiologie appears as Clinical Research in Cardiology, and the Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, though it has kept its German name, now publishes mainly English-language articles, with very few exceptions. For our journal, a complete switch to English is out of the question – both for our readers’ sake and because we do not want to abandon German as a scientific language. Yet we cannot ignore the importance of English, either. The English language is especially important for scientific authors, whose articles will reach a wider audience if they are written in English.

Many periodicals are already published in two languages. This approach has been adopted, for example, by the Hungarian Medical Journal and the Jornal de Pediatria (Brazil), and in Germany by the Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, too, has now decided to publish an English-language edition. Starting this year, our scientific articles will also appear in English in the online journal Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. The original as well as the translated articles will thus be available over the Internet to all interested readers free of charge (open access). Our authors will not be put to any additional trouble, as Deutsches Ärzteblatt itself will organize and pay for the translations. The first edition is planned to appear on 21 January 2008 (www.aerzteblatt-international.de). The printed edition of Deutsches Ärzteblatt will not look very different: only the new page numbering will reflect the shift to bilingualism.

Our new international edition is not meant as an attempt to compete with the major international journals. We would be very glad, however, if Deutsches Ärzteblatt with its new English edition were to become more attractive to authors than before, so that we can improve the quality of our offerings still further – for the benefit not just of our international readers, but particularly of the German-speaking readers who form our core audience.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author states that he has no conflict of interest as defined by the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Lippert H. Rückzug der deutschen Sprache aus der Medizin? Med Klin. 1978;73:487–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro FA. Englisch oder Deutsch? Die Sprache der Medizin aufgrund der in der Deutschen Medizinischen Wochenschrift erschienenen Literaturangaben (1920-1995) Dtsch Med Wschr. 1996;121:1561–1566. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarro FA. Die Sprache der Medizin in der Schweiz von 1920 bis 1995. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1997;127:1565–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navarro FA. Die Sprache der Medizin in Österreich (1920-1925) Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1996;108:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro FA. L’importance de l’anglais et du francais sur la base des references bibliographiques de travaux originaux publies dans La Presse Medicale. La Presse Medicale. 1995;24:1547–1551. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro FA. De taal in de geneeskunde afgeleid uit literatuurreferenties van oorspronkelijke stukken in het Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (1930-1995) Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1996;24:1263–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro FA. El idioma de la medicina a traves de las referencias bibliograficas de los articulos originales publicados en Medicina Clinica durnate 50 anos (1945-1995) Med Clin (Barc) 1996;107:608–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenhard MS, Johnson TRC, Himsl I, et al. Obstetrical and gynecological writing and publishing in Europe. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;129:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graddol D. English Next. Why global English may mean the end of English as a foreign language. British Council. 2006 www.britishcouncil.org/learning-research-english-next.pdf, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egger M, Zellwäger-Zähner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet. 1997;350:326–329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galandi D, Schwarzer G, Antes G. The demise of the randomized controlled trial: bibliometric study of the German-language health care literature, 1948-2004. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-30. DOI 10.1186/1471-2288-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmucker C, Blümle A, Antes G, Lagrèze W. Randomisierte kontrollierte und kontrollierte klinische Studien in deutschsprachigen, ophthalmologischen Fachzeitschriften. Der Ophthalmologe. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00347-007-1618-6. DOI 10.1007/s00347-007-1618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbeitskreis Deutsch als Wissenschaftssprache: Sieben Thesen zur deutschen Sprache in der Wissenschaft. www.hartmann-in-berlin.de/7thesen/start. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinrich H. Sprache und Wissenschaft. In: Kalverkämper H, Weinrich H, editors. Deutsch als Wissenschaftssprache. Tübingen: Narr; 1986. pp. 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiewe J. Was spricht dafür, das Deutsche als Wissenschaftssprache zu erhalten? In: Pörksen U, editor. Die Wissenschaft spricht englisch? Göttingen: Wallstein; 2005. pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters UH. Ist Deutsch als Sprache der Psychiatrie noch up to date? Fortschr Neurol Psychiat. 2007;75:55–58. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]