Abstract

Inhibitors of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase [PNMT, the enzyme that catalyzes the final step in the biosynthesis of epinephrine (Epi)] may be of use in determining the role of Epi in the central nervous system. Here we describe the synthesis and characterization of 7-SCN tetrahydroisoquinoline as an affinity label for human PNMT.

Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT; EC 2.1.1.28) catalyzes the terminal step in catecholamine biosynthesis, i.e., the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet)-dependent conversion of norepinephrine to epinephrine (adrenaline).1,2

PNMT has been found in high levels in the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla1 where epinephrine is secreted as a hormone, particularly during periods of stress. The enzyme has also been found in the medulla oblongata and the hypothalamus,3,4 and in the sensory nuclei of the vagus nerve,5 where epinephrine is proposed to function as a neurotransmitter. It has been suggested that central nervous system (CNS) epinephrine may be involved in the a wide range of activities including central control of blood pressure and respiration,4,6 the secretion of hormones from the pituitary,7 and the control of exercise tolerance.8 More recently it has been suggested that CNS epinephrine may be responsible for some of the neurodegeneration found in Alzheimer’s disease.9–11

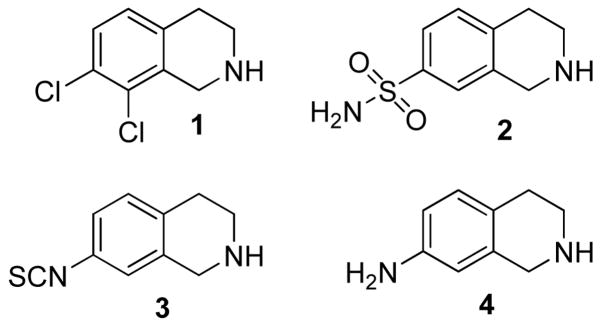

It has been shown that CNS-active PNMT inhibitors such as SK&F 64139 (1, Figure 1) provide a decrease in brain epinephrine content and peripheral blood pressure when administered to hypertensive rats.12 By contrast, PNMT inhibitors such as SK&F 29661 (2, Figure 1) that do not cross the blood–brain barrier, are ineffective in lowering blood pressure.6 However, interpretation of these results is complicated by the fact that most PNMT inhibitors also interact with central α2-adrenoceptors.13 Thus, it is not clear whether the observed decrease in blood pressure upon administration of CNS-active PNMT inhibitors is caused by a reduction in levels of brain epinephrine due to PNMT inhibition, or as a result of the interaction of the inhibitors with α2-adrenoceptors. Taken together these observations suggest that it will be difficult to assess the role of CNS epinephrine without developing specific inhibitors of PNMT that have the ability to cross the blood brain barrier but do not react with α2-adrenoceptors. As a consequence there have been numerous studies aimed at developing potent and specific PNMT inhibitors. While many of these inhibitors have been benzylamine derivatives,14,15 the majority have contained the tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) nucleus.16–18

Figure 1.

Structures of PNMT inhibitors described in the text.

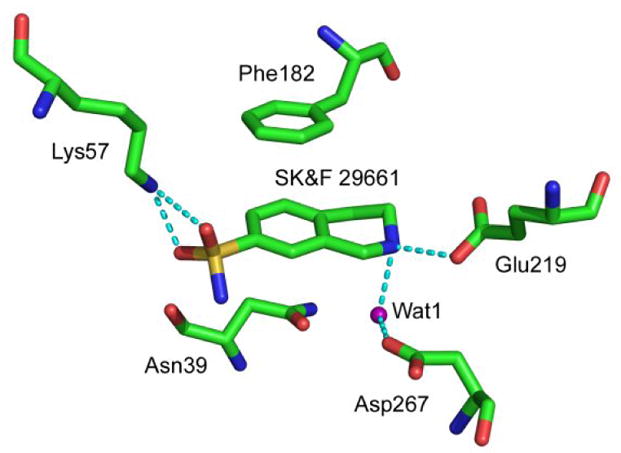

Recently, the X-ray structure of hPNMT in complex with both 2 and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine was determined.19 The structure shows that a lysine residue, Lys57, interacts with the sulfonamide oxygens of 2 (Figure 2). This suggested to us that it may be possible to target this residue with an affinity label designed to cross the blood-brain barrier yet have greater specificity for PNMT than 1. Isothiocyanates have been successfully used as affinity labels as they react readily with lysine residues to form stable N,N′-dialkylthioureas.20,21 Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), for example, is commonly used to label lysine residues in the active site of enzymes such as H+,K+-ATPases,22–24 while benzyl isothiocyanates are used to label cytochrome P450 enzymes.25–27 Given the proximity of the 7-aminosulfonyl group to Lys57 and the fact that 2 binds to hPNMT with sub-micromolar affinity,28 it appeared that 7-isothiocyanato THIQ (3) may act as an efficient affinity label for the enzyme. Here we describe the synthesis of 3 and its reaction with hPNMT.

Figure 2.

Active site of human PNMT (hPNMT) highlighting interactions with SK&F 29661 (2). Data from PDB ID 1HNN.

Compound 3 was synthesized by reaction of 429 with thiophosgene in acetone at 0 °C.30 In a preliminary experiment the IC50 value for 3 was determined at a phenylethanolamine (PEA) concentration of 100 μM (~ Km, Table 1) using standard assay conditions.31 A value of 80 ± 8 nM was obtained, which increased to 260 ± 20 nM when the PEA concentration was increased to 500 μM (5 × Km). These results confirmed that 3 was an excellent inhibitor of hPNMT and suggested that inhibition was competitive with phenylethanolamine with a Ki of ca. 40 nM.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters (± SEM)for wt and K57A hPNMT

| WT | K57A | |

|---|---|---|

| kcat (min−1) | 2.8 ± 0.1a | 4.0 ± 0.7a |

| Km PEA (μM) | 100 ± 4a | 1300 ± 10a |

| Km AdoMet (μM) | 3.9 ± 0.2a | 12 ± 2a |

| Ki 2 (μM) | 0.12 ± 0.02a | 6.9 ± 0.1a |

| Ki(app) 3 (μM) | 0.05 ± 0.01b | 2.6 ± 0.5b |

Data from reference28

Ki (app) values determined under standard assay conditions without regard to any inactivation occurring.

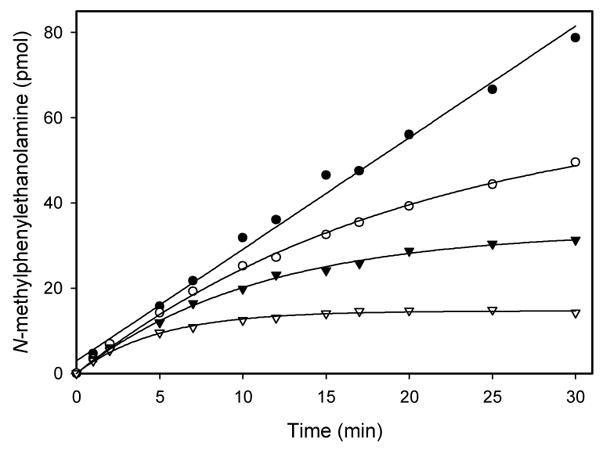

Figure 3 shows that, in the absence of inhibitor, the hPNMT-catalyzed methylation of phenylethanolamine proceeds in a linear fashion. By contrast, in the presence of 3, the rate of methylation decreases in a time-dependent manner. In these experiments there is no pre-incubation of enzyme and inhibitor and the reaction time course can be described by a slow-onset inhibition equation (eq 1), where vs is the terminal steady-state velocity, vo is the initial velocity, and kobs is a pseudo first order rate constant for the onset of inactivation.32, 33

Figure 3.

Reaction time course for PNMT activity in the absence (●) and presence of 100 nM (○), 200 nM (▼;)and 500 nM (▽) 3. After appropriate time intervals the reaction was quenched and the extent of product formation was measured.31

| (eq 1) |

The best fits of the data in Figure 1 were obtained by fixing vs = 0. This result is consistent with 3 acting as an affinity label for, if the enzyme was totally inactivated, the terminal velocity (vs) would be zero.

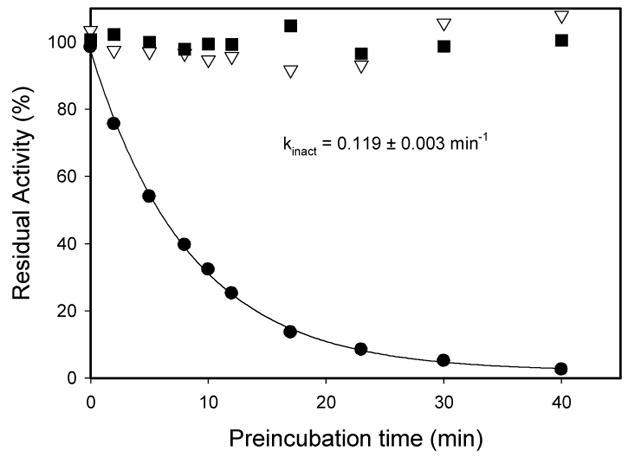

To explore this possibility we then carried out a dilution experiment with the results shown in Figure 4. When hPNMT was incubated with 2.5 μM 3 at pH 7.5 and 30 °C, the enzyme was progressively inactivated. The loss of activity occurred according to a single-exponential decay function (kobs = 0.12 ± 0.01 min−1), and resulted in almost totally inactivated enzyme (<0.5% residual activity in most cases). Conversely, there was virtually no change in activity when the enzyme was incubated at 30 °C in the absence of inhibitor. In an additional control reaction, the enzyme was incubated with 2 under the same conditions. Upon dilution the enzyme recovered essentially full activity, a clear indication that inhibition by 2 is reversible, in direct contrast to the loss of activity observed upon incubation with 3.

Figure 4.

Irreversible inactivation of hPNMT with 3. hPNMT (1 μM) was incubated in the absence of inhibitor (■), with 2.5 μM 2 (▽), or with 2.5 μM 3 (●). At the indicated times aliquots were diluted 1:50 into the standard assay mixture and the PNMT activity determined.

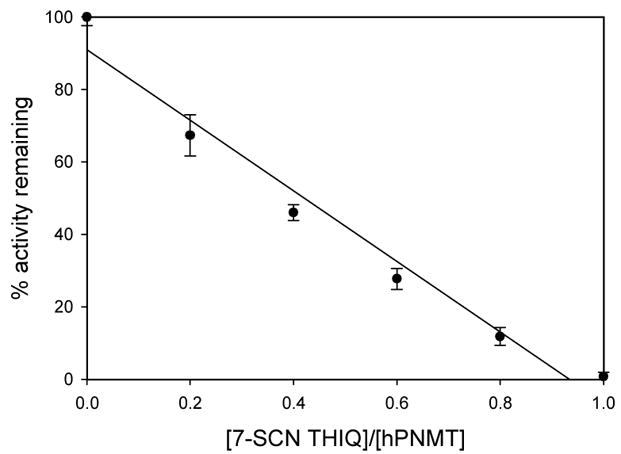

To determine the extent of incorporation of label into hPNMT the enzyme was incubated for 1 h with varying concentrations of 3. After that time the residual activity was measured. Figure 5 shows that labeling is stoichiometric with 0.95 ± 0.2 molecules of 3 per active site.

Figure 5.

Stoichiometry of inactivation of hPNMT

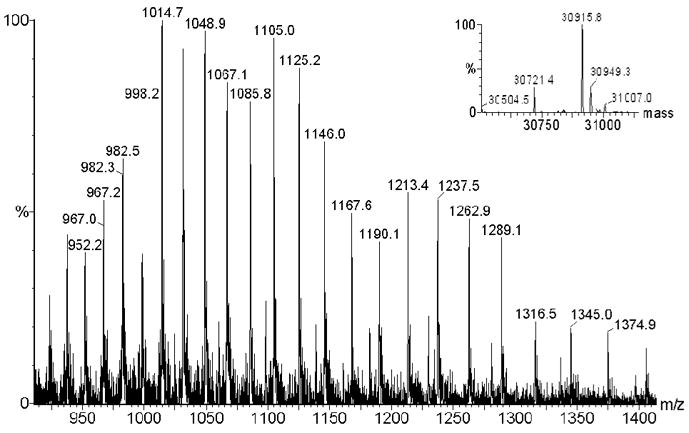

The experiments described thus far cannot conclusively distinguish between a covalently bound inhibitor and a slow onset, tight-binding inhibitor.34 However, it is unlikely that a noncovalent complex will survive the conditions employed in a LC-MS experiment.35 Accordingly, LC/MS was used to obtain the molecular weights of the wild-type and the 3-inactivated hPNMT. Reaction of 3 with a single lysine residue would result in the addition of 190 to the molecular weight of the enzyme

The deconvoluted mass spectrum of WT hPNMT provides a molecular weight of 30,725 Da which is consistent with the enzyme lacking its N-terminal methionine.36 By contrast the spectrum of the labeled enzyme provides a molecular weight of 30,916 Da (Figure 6). The mass difference of 191 suggests that the reaction is indeed irreversible, and is consistent with the data in Figure 5 indicating that a single residue is labeled.

Figure 6.

Multiply charged mass spectrum of hPNMT labeled with 3. The inset shows the Maxent deconvolution. The theoretical Mr are 30724 Da and 30914 Da for unlabeled and labeled hPNMT, respectively.

In an attempt to identify the residue labeled by 3 a sample of labeled enzyme was subjected to trypsin digest and analyzed by LC-MS. An identical treatment of unlabeled hPNMT provided a control. Tryptic digest of the wild-type enzyme is expected to provide 27 fragments arising from cleavage at 7 lysine and 19 arginine residues. Of these we were able to detect 21 individual peptides by LC-MS. These included four of the peptides arising from cleavage at lysine, each of which was also seen in the digest of the labeled enzyme. In an attempt to increase coverage of the digest we turned to MALDI TOF analysis of the digestion mixture. This enabled us to see an additional 5 peptides, including 2 arising from cleavage at lysine, only one of which was present in the digest of the labeled enzyme. Overall, this left us with two candidate residues, Lys57 and Lys143.

A further digestion was carried out, this time using LysC proteinase which cleaves solely at lysine residues. In this instance, only 3 recognizable peptides were observed in the MALDI mass spectrum. These peptides spanned hPNMT residues 136–151, 249–269 and 270–278. Fortuitously, the covered region included Lys143 and, as all three peptides were observed in LysC digests of both labeled and unlabeled enzyme, it was concluded that Lys57 was the labeled residue. Details of the mass spectrometry analyses are provided as supplementary material.

Another way to confirm that Lys57 is the residue being labeled by 3 is to examine the extent of labeling in the absence of any possible interaction. Towards this end we utilized the his6-tagged hPNMT K57A mutant.28 A kinetic analysis, detailed in Table 1, showed that the kcat for the reaction was largely unaffected, as was the Km for AdoMet. However, the Km for PEA increased about 13-fold suggesting most of the effect of this mutation was on the binding of this substrate. Both 2 and 3 were found to be competitive inhibitors of hPNMT K57A. As might be expected given the interaction shown in Figure 2, the affinity of this variant for 2 decreased 60-fold, while the affinity for 3 decreased 50-fold. Most importantly the interaction between the K57A mutant and 3 was found to be reversible in a dilution experiment such as that in Figure 4, and by LC-MS analysis where a Mr of 31,614 was obtained for both labeled and unlabeled enzyme (data not shown). Taken together, the results suggest that 3 is an efficient and selective affinity label for hPNMT.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Axelrod J. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:1657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirshner N, Goodall M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957;24:658. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Johannson O. Acta Physiol Scand. 1973;89:286. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1973.tb05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Johannson O. Brain Res. 1974;66:235. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickel VM, Chan J, Park DH, Joh TH, Milner T. J Neurosci Res. 1986;15:439. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490150402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black J, Waeber B, Bresnahan MR, Gavras I, Gavras H. Circ Res. 1981;49:518. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley WR, Terry LC, Johnson MD. Endocrinology. 1982;110:1102. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-4-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trudeau F, Brisson GR, Peronnet F. Physiol Behav. 1992;52:389. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90289-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke WJ, Chung HD, Huang JS, Huang SS, Haring JH, Strong R, Marshall GL, Joh TH. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:532. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke WJ, Chung HD, Marshall GL, Gillespie KN, Joh TH. J Am Ger Soc. 1990;38:1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke WJ, Galvin NJ, Chung HD, Stoff SA, Gillespie KN, Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Brain Res. 1994;661:35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hieble JP, McCafferty JP, Roesler JM, Pendleton RG, Gessner G, Carey R, Sarau HM, Goldstein M. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1983;5:889. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198309000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatelain RE, Manniello MJ, Dardik BN, Rizzo M, Brosnihan KB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunewald GL, Monn J, Rafferty MF, Borchardt RT, Krass P. J Med Chem. 1982;25:1248. doi: 10.1021/jm00352a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunewald GL, Dahanukar VH, Ching P, Criscione KR. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3539. doi: 10.1021/jm9508292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunewald GL, Dahanukar VH, Teoh B, Criscione KR. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1982. doi: 10.1021/jm9807252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grunewald GL, Dahanukar VH, Jalluri RK, Criscione KR. J Med Chem. 1999;42:118. doi: 10.1021/jm980429p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunewald GL, Caldwell TM, Li Q, Criscione KR. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3315. doi: 10.1021/jm980734a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin JL, Begun J, McLeish MJ, Caine JM, Grunewald GL. Structure. 2001;9:977. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyte J. Structure in Protein Chemistry. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langdon RG. Method Enzymol. 1977;46:164. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(77)46017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Festy F, Lins L, Gallet X, Robert JC, Thomas-Soumarmon A. J Membr Biol. 1998;165:153. doi: 10.1007/s002329900429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morii M, Takeguchi N. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallmark B, Briving C, Fryklund J, Munson K, Jackson R, Mendlein J, Rabon E, Sachs G. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goosen TC, Kent UM, Brand L, Hollenberg PF. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:1349. doi: 10.1021/tx000133y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langouet S, Furge LL, Kerriguy N, Nakamura K, Guillouzo A, Guengerich FP. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:245. doi: 10.1021/tx990189w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima M, Yoshida R, Shimada N, Yamazaki H, Yokoi T. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Q, Gee CL, Lin F, Tyndall JD, Martin JL, Grunewald GL, McLeish MJ. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7243. doi: 10.1021/jm050568o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grunewald GL, Dahanukar VH, Caldwell TM, Criscione KR. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3997. doi: 10.1021/jm960235e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To an ice-water cooled solution of CSCl2 (44 mg, 0.38 mmol) in acetone (10 mL) was added 7-amino-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline dihydrochloride (70 mg, 0.32 mmol) in H2O (5 mL) over 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to yield a yellow residue which was recrystallized from cold MeOH/Et2O to yield white crystals (30 mg, 41%): mp > 250 °C; FT-IR (KBr): υ 2060 (N=C=S stretching); 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.63 (br s, 2 H, NH2+), 7.36–7.32 (m, 3 H, ArH), 4.23 (s, 2 H, H-1), 3.35–3.33 (dd, J = 4.78 Hz, 2 H, H-3), 3.03–2.99 (t, 2 H, J = 6.34 Hz, H-4); MS(EI) m/z 190 (M+), 189, 161 (M+ − CH2NH2), 132 (M+ − N=C=S). Anal. (C10H11ClN2S) Calculated: C, 52.98; H, 4.89; N, 12.36; Found: C, 53.00; H, 5.00; N, 12.32.

- 31.The PNMT reaction was followed by monitoring the transfer of a tritiated methyl group from AdoMet to PEA. A standard assay mixture contained potassium phosphate (50 mM, pH 8.0), PEA (200 μM) and AdoMet including [3H]-AdoMet (5 μM), in a total volume of 250 μL. For determination of kinetic constants, PEA concentrations were between 50 and 300 μM (for hPNMT), 0.5 and 3.0 mM (for K57A variant), while AdoMet was varied between 2.5 and 40 μM. For Ki determinations, AdoMet concentration was maintained at 5 μM, while PEA and inhibitor were varied between 20 and 500 nM (wt), and between 0.5 and 5 μM (K57A). Following the addition of enzyme, the reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 30 minutes, and then quenched by the addition of 0.5 M boric acid (250 μL, pH 10). Two mL of a mixture of toluene/isoamyl alcohol (7:3) were added, and the samples were vortexed for 30 s. The phases were separated by centrifugation and an aliquot of the organic phase (1 mL) was removed and added to 5 mL of scintillation fluid (Cytoscint, ICN). The radioactivity was quantitated by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

- 32.Williams JW, Morrison JF. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:437. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copeland RA. Enzymes Second Edition: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism and Data Analysis. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2000. p. 305. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harpel MR, Horiuchi KY, Luo Y, Shen L, Jiang W, Nelson DJ, Rogers KC, Decicco CP, Copeland RA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6398. doi: 10.1021/bi012126u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight WB, Swiderek KM, Sakuma T, Calaycay J, Shively JE, Lee TD, Covey TR, Shushan B, Green BG, Chabin R, et al. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2031. doi: 10.1021/bi00059a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caine JM, Macreadie IG, Grunewald GL, McLeish MJ. Prot Express Purif. 1996;8:160. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.