Abstract

Dopamine promotes sodium excretion, in part, via activation of D1 receptors in renal proximal tubules (PT) and subsequent inhibition of Na, K-ATPase. Recently, we have reported that oxidative stress causes D1 receptors-G-protein uncoupling via mechanisms involving Protein Kinase C (PKC) and G-protein Coupled Receptor Kinase 2 (GRK2) in the primary culture of renal PT of Sprague Dawley (SD) rats. There are reports suggesting that redox-sensitive nuclear transcription factor, NF-κB, is activated in conditions associated with oxidative stress. This study was designed to identify the role of NF-κB in oxidative stress–induced defective renal D1 receptor –G-protein coupling and function. Treatment of the PT with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 50 μM/20 min) induced the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, increased PKC activity, and triggered the translocation of GRK2 to the proximal tubular membranes. This was accompanied by hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors and defective D1 receptor-G-protein coupling. The functional consequence of these changes was decreased D1 receptor activation-mediated inhibition of Na, K-ATPase activity. Interestingly, pre-treatment with pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC, 25 μM/10min), an NF-κB inhibitor, blocked the H2O2-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB, increase in PKC activity, as well as GRK2 translocation and hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors in the proximal tubular membranes. Furthermore, PDTC restored D1 receptor G-protein coupling and D1 receptor agonist-mediated inhibition of the Na, KATPase activity. Therefore, we suggest that oxidative stress causes nuclear translocation of NF-κB in the renal proximal tubules, which contributes to defective D1-receptor-G-protein coupling and function via mechanism involving PKC, membranous translocation of GRK 2, and subsequent phosphorylation of dopamine D1 receptors.

Keywords: G-Protein coupled Receptor Kinase 2 (GRK 2), Protein Kinase C (PKC), SKF-38393, Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), Oxidative stress, Dopamine

INTRODUCTION

Dopamine promotes sodium excretion, in part, via activation of D1 receptors in renal proximal tubules (PT) and subsequent inhibition of Na, K-ATPase (1-4). However, in states associated with oxidative stress; such as aging, diabetes, and hypertension, this effect of dopamine is not seen due to defective D1 receptor-G-protein coupling resulting from ligand-independent phosphorylation of D1 receptor (5-7). Several studies suggest that oxidative stress increases protein kinase C (PKC) in different cell types, including renal proximal tubular cells (8-10). Moreover, G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), which belong to the family of serine/threonine kinases, play an important role in phosphorylation and subsequent desensitization of G-protein coupled receptors (11).

Dopamine D1 receptors can serve as a substrate for GRK 2, 3, and 5 (12). Recently, we have reported that oxidative stress, induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), caused D1-receptor-G protein uncoupling in the primary cultures of PT from Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (13). This uncoupling resulted from H2O2-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC), subsequent membranous translocation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK 2) and phosphorylation of D1 receptors (13). In addition, studies from our laboratory have reported agonist-independent phosphorylation of D1 receptors via GRK 2 in streptozotocin (STZ-treated) and obese Zucker rats, animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, respectively, which exhibit oxidative stress. (14,15). Interestingly, supplementation with the antioxidant, tempol, prevented GRK 2 membranous translocation and subsequent D1 receptor hyperphosphorylation and restored D1-receptor-G-protein coupling and function in these animals (14,15).

The transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) participates in the expression of a wide variety of genes that are involved in the regulation of many cellular mediators of immune and inflammatory responses (16). NF-κB was originally recognized as a nuclear factor capable of binding defined sites in the κ-immunoglobulin enhancer in B cell lymphocytes (17). However, it is now well known that NF-κB is ubiquitously expressed in most cell types and is a dimer that comprises five subunits of the Rel family (16). These subunits include p50, p52, p65 (Rel A), c-Rel, and Rel-B, and they can homodimerize and heterodimerize in various combinations. Most commonly, NF-κB consists of two polypeptides of 50 KDa (p50) and 65 KDa (p65) (18). In the resting cells, NF-κB resides in the cytoplasm in an inactive form physically associated with an inhibitor protein known as inhibitory κB (IκB) protein (18). The list of NF-κB activators includes, but not limited to, bacterial and viral infections, cytokines [tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)], free radicals, and oxidants (19). In-vitro and in-vivo studies in animal models of sepsis have shown that activation of this transcription factor is rapid and occurs within minutes after the microbial challenge (18). Activation of NF-κB results from the phosphorylation of its IκB protein. This phosphorylation is mediated via IκB protein kinases (IKKs), which causes proteolytic degradation of IκB by 26S proteosome. Subsequently, degraded IκB allows NF- κB to translocate into the nucleus, where it regulates the expression of many genes (18).

The present study was designed as a follow-up to our recent report (13) to determine whether NF-κB plays a role in H2O2-mediated defective D1 receptor G-protein coupling. First, we utilized both, western blotting and immunofluorescence techniques to detect nuclear translocation of NF-κB, an index of NF-κB activation after the exposure of PT of SD rats to H2O2. Second, we used pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), an inhibitor of NF-κB to study the role of NF-κB in H2O2-induced activation of PKC and subsequent translocation of GRK 2 to the proximal tubular membranes. Finally, we investigated the involvement of NF-κB in oxidative stress-induced defective D1 receptor signaling by measuring D1 receptor phosphorylation, D1-receptor-Gprotein coupling, and SKF-38393, a D1 receptor agonist-mediated inhibition of Na-KATPase activity, in the presence and absence of PDTC.

METHODS

Materials

SKF-38393 [(±)-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-(1H)-3-benzazepine-7,8-diol hydrochloride], a D1 receptor agonist, and PDTC (pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). [35S]GTPγS (guanosine 5’-(γ-thio)triphosphate[35S]) was purchased from NEM Life Sciences. D1 receptor antibody was purchased from either Chemicon (Temecula, CA) for immunoprecipitation studies or Alpha Diagnostics (San Antonio, TX) for western blotting studies. Phosphoserine antibody was bought from Calbiochem NovaChem (San Diego, CA). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies, GRK 2 polyclonal antibody, NF-κB p65 polyclonal antibody, NF-κB p50 polyclonal antibody, and protein A/G-agarose beads were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); protease inhibitor cocktail was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). Nuclear and cytosolic extraction kit was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Non radioactive PKC assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). All other chemicals of highest purity available were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Methods

The animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Houston Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We used 6-10 weeks old male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 200-250 g (Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, IN). All rats were maintained in a temperature controlled animal care facility, with 12-h light and dark cycle. Rats were allowed free access to tap water and standard rat chow (Purina Mills, St. Louis, MO).

Preparation of renal proximal tubules (PT) suspension

An in situ enzyme digestion procedure as previously described was used to prepare renal proximal tubules (6). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body wt ip), abdomen was opened, aorta was catheterized with PE- 50 tubing and kidneys were perfused with collagenase and hyaluronidase. The kidneys were removed and kept in ice-cold oxygenated Krebs buffer containing (in mM): 1.5 CaCl2, 110 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 KH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, and 2 HEPES (pH 7.6). Transverse sections of the kidneys were obtained, and superficial cortical tissue slices (rich in proximal tubules) were dissected out with a razor blade. The cortical slices were kept in fresh Krebs buffer. Enrichment of proximal tubules was carried out using 20% ficoll in Krebs buffer. The band at ficoll interface was collected and washed in Krebs buffer by centrifugation at 250g for 5 min. Cell viability was determined in this fraction using the Trypan blue exclusion test. This fraction of PT was used to prepare the proximal tubular membranes. The proximal tubular fraction was suspended and homogenized in homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitor cocktail; pH 7.4). The suspension was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 25 min at 4°C. The upper fluffy layer of the pellet was considered to be proximal tubular membrane fraction. The proximal tubular membrane fraction was resuspended in the homogenization buffer and used for western blotting, immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting, and radioligand binding studies (7). Protein was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Induction of oxidative stress

The renal proximal tubule (PT) fragments from Sprague Dawley rats were washed with Kreb’s Henseliet Buffer (KHB), and exposed to either vehicle or 50 μM H2O2 for 20 min to induce oxidative stress (13). In experiments involving western blotting, radioligand binding, and measurement of Na, K-ATPase activity, cells were pretreated with an inhibitor of NF-κB (PDTC, 25 μM/ 10 min). For immunofluroescence detection of nuclear translocation of NF-κB, cells were pretreated with ascorbic acid (Vitamin C, 60 μg/ ml for 15 min). Subsequently, PT were homogenized and processed for membrane preparation, by the methods described in the previous section. In some experiments PT were exposed to PDTC alone and measurements of different parameters were made.

Western blotting of nuclear and cytosolic NF-κB and GRK 2

Both, the nuclear and cytosolic fractions of PT were isolated by a commercially available NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic extraction reagent Kit (Pierce Biotechnology Rockford, IL). Proximal tubular nuclear and cytosolic fractions (20 μg proteins) and membrane fractions (10 μg proteins) for NF-κB and GRK2, respectively, were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The resolved proteins were electrophoretically transblotted onto a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA). The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal NF-κB p65 (1: 200), NF-κB p50 (1:500), or GRK2 (1:500) antibodies, separately, for 60 min. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000 for NF- κB p65 & p50 subunits and 1:4000 for GRK2) was then added for 60 min at room temperature. The PVDF membranes were incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX), and the bands were visualized on X-ray film. The bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using Scion Image Software provided by the National Institutes of Health.

Immunofluorescence detection of nuclear translocation of NF-κB

Immunofluorescence studies were carried out by a modified method of Brismar et al. (20). Proximal tubular epithelial cells (80 confluent) were grown on poly D-lysine (50 μg/ml) coated glass coverslips and treated with drugs followed by the addition of ice-cold 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS to stop the reaction. NF-κB primary antibody was incubated in a blocking buffer (PBS with 5% normal goat serum, 0.1% triton X-100) for 1hr. Texas red conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody, (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) was used to probe primary antibody for 1-hr in the dark. The cells were then washed with PBS containing 0.1% triton X-100 after primary and secondary antibodies incubation. The coverslips were mounted with a Vectashield mounting medium with nuclear dye DAPI (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) and scanned under fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX81 series Automated Microscope) using specific filters for Texas red and DAPI.

Protein Kinase C (PKC) Activity Measurement

The PKC activity in PT was measured using the method described previously in our laboratory (10). Briefly, the reaction was carried out in a final volume of 25 μl containing (mM) 20 HEPES, pH 7.4, 1.3 CaCl2, 1 DTT, 10 MgCl2, 1 ATP, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.2 mg/ml phosphatidylserine, and 2 μg fluorescent PepTag C1 peptide substrate (P-L-S-R-T-L-S-V-A-A-K, amino acid sequence). A dye molecule attached to the peptide substrate imparts the hot pink fluorescence. The reaction was started by the addition of 25–50-μg proteins and carried out for 30 mins at 30°C. The samples were heated at 95°C for 10 mins to stop the reaction. The PKC-mediated phosphorylation on PepTag C1 peptide was separated from the nonphosphorylated peptide by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose. The phosphorylated peptide was cut under UV light, agarose was melted, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded using excitation and emission wavelengths of 568 and 592 nm, respectively, on a spectrofluorometer. The fluorescence intensity was read on a standard curve prepared by using pure PKC enzyme (0–40 ng) as standard supplied with the kit. The PKC enzyme (catalog no. V5261; Promega) supplied was purified from rat brain and is greater than 90% pure as determined by SDS-PAGE, which consists primarily of α, β, and γ isoforms with lesser amount of δ and ζ isoforms.

Immunoprecipitation of D1 receptors

D1 receptors were immunoprecipitated using the method of Sanada et al. (21), which has been used in our ptrevious studies (22). Briefly, cell membranes (1.5 mg protein/ml) were incubated with 10 μg rabbit dopamine D1 receptor antibody in IP buffer (140mM NaCl, 3mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 Mm KH2PO4, 1 mM orthovanadate, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium cholate, 0.1% SDS, 1mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.4) overnight followed by incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads for 2 hours. The ternary complex of D1 receptor antibody-protein A/G agarose was washed with IP buffer and then with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The complex was dissociated in 2x Laemmeli buffer and used for electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Detection of serine phosphorylation of D1 receptors

The immunoprecipitates (10 μl) were resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and the proteins were electro-transferred on a PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 4% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% tween 20 (PBST). A specific phosphoserine antibody (1:200) was used to detect serine phosphorylation on D1 receptors. HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1: 3000) was used to probe phosphoserine antibody and the bands were visualized with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent kit (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX).

Measurement of [35S]GTPγS binding

To determine D1 receptor G protein coupling, the [35S]GTPγS binding assay was performed as described earlier (23). The reaction mixture contained 25 mM HEPES, 15 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothrietol, 100mM NaCl (pH 8.0). In the presence of ~ 100,000 cpm of [35S]GTPγS, 5 μg proximal tubular membrane protein was incubated with various concentrations of SKF-38393 (10-9-10-6 mol/l) for one hour at 30°C. Non specific binding was determined by adding 100 μM unlabeled GTP to the assay media. Specific binding was calculated as the difference between total and nonspecific binding.

Na, K-ATPase assay

The Na, K-ATPase activity was measured as previously described (6,14,15). Vehicle, H2O2-treated, and PDTC + H2O2-treated PT were incubated without and with SKF-38393, a D1 receptor agonist, for 15 min at 37°C. The Na, K-ATPase activity was measured as the function of liberated inorganic phosphate (Pi) in triplicates. The Na, K-ATPase activity was calculated as the difference between the total and ouabain-insensitive ATPase activity and is represented as percent of basal, where basal was normalized to 100%.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as Means ± SEM. Differences between means were evaluated using the unpaired t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc tests (Newman-Keuls), for comparisons between groups and for within group variations, respectively. The P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done using Graph Pad Prism, version 3.02 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Effect of H2O2 and PDTC on NF-κB

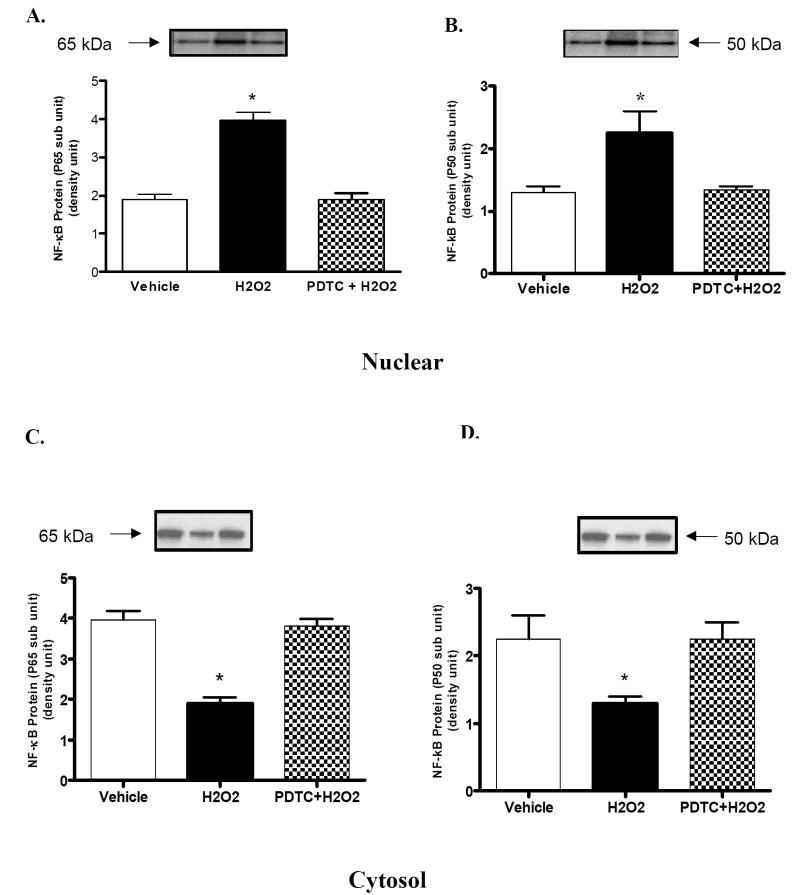

Treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (20 min/ 50 μM) caused translocation of NF-κB from the cytosol to the nucleus. This is reflected by increased expression of NF-κB p65 and p50 subunits (Fig 1A and Fig 1B), in the nuclear fraction, and decreased expression of both subunits in the cytosolic fraction (Fig 1C and Fig 1D). Pretreatment with PDTC, NF-κB inhibitor, prevented H2O2-mediated translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus (Fig 1A and Fig 1B).

Figure 1. Effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and NF-κB inhibitor (PDTC) on translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus.

A and B) representative blots and densitometric analysis of NF-κB (p65 subunit) and (p50 subunit) protein respectively, in the nuclear fraction of renal proximal tubules (PT). C and D) representative blots and densitometric analysis of NF-κB (p65 subunit) and (p50 subunit) protein respectively in the cytosolic fraction of PT. Results represent mean ± SEM (N=3 animals). Pretreatment with PDTC prevented H2O2-mediated increase in nuclear translocation of NF-κB. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle using One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test.

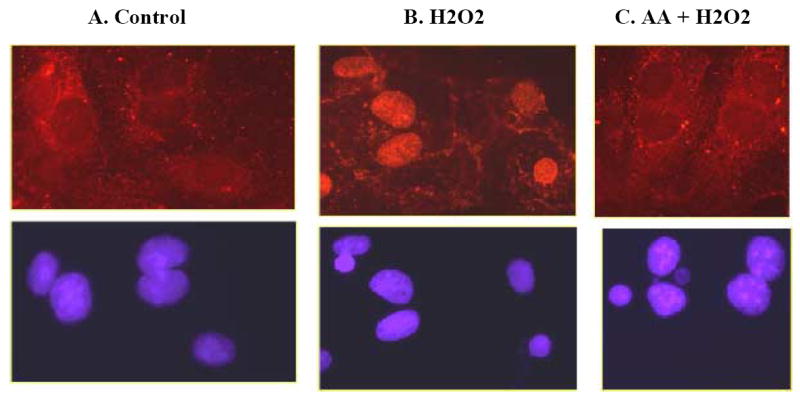

Effect of the oxidant (H2O2) and the antioxidant (ascorbic acid) on NF-κB: Immunofluorescence studies

In vehicle-treated cells, NF-κB was mainly distributed in the cytosol (Fig 2A, upper panel). Treatment with the oxidant, H2O2 (20 min/ 50 μM), caused an increase in the nuclear fluorescence signal of NF-κB p65 subunit (Fig 2B, upper panel). Ascorbic acid (AA, 60μg/ml for 15min) abolished H2O2-induced increase in nuclear signal of NF-κB and caused redistribution of NF-κB p65 subunit to the cytosol (Fig 2C, upper panel).

Figure 2. H2O2 causes nuclear translocation of NF-κB in intact renal proximal tubular epithelial cells.

The nuclear translocation of NF-κB was determined by immunofluorescence (details in methods). H2O2 (20 min/ 50 μM) caused an increase in nuclear fluorescence signal of NF-κB (Fig 2B, upper panel). Ascorbic acid (AA, 60 μg/ ml for 15 min) abolished H2O2-induced increase in nuclear signal of NF-κB (Fig 2C, upper panel). Lower panel represents cells in the corresponding plates showing nuclei stained with DAPI.

Role of NF-κB in H2O2-mediated activation of PKC and subsequent translocation of GRK 2 to the membrane

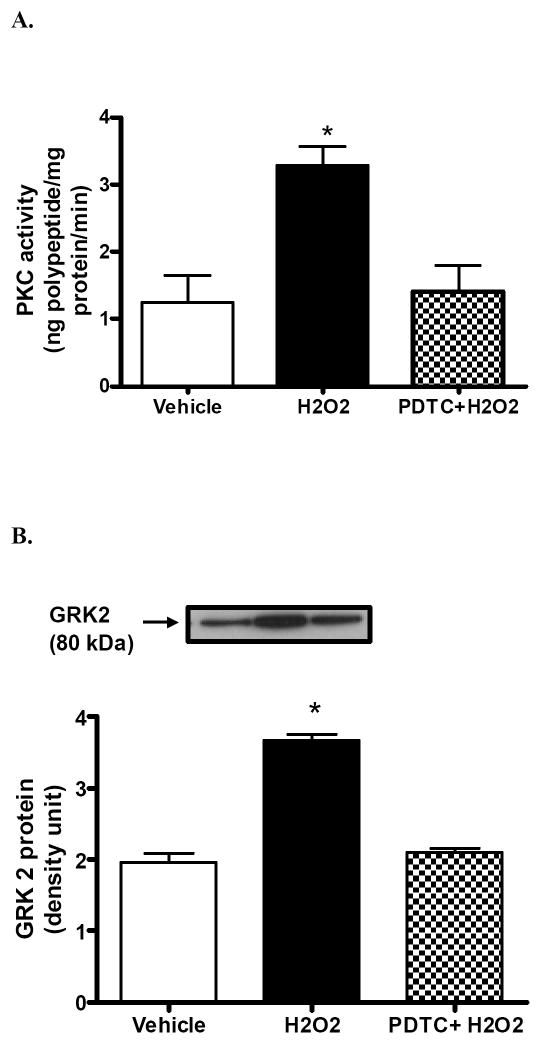

Hydrogen peroxide (20 min/ 50 μM) significantly increased the activity of PKC in the renal proximal tubules of SD rats (Fig 3A). Pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC, blocked H2O2-mediated increase in PKC (Fig 3A). Similarly, H2O2 significantly increased the translocation of GRK 2 to the proximal tubular membranes (Fig 3B). Pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC (10min/25 μM), prevented H2O2-mediated membranous translocation of GRK 2 (Fig 3B). These results suggest a role of NF-κB in oxidative stress-induced activation of PKC and subsequent translocation of GRK 2 to the proximal tubular membrane.

Figure 3. H2O2-mediated activation of PKC and subsequent translocation of GRK 2 to the membrane occurs via a mechanism involving NF-κB.

A) Upper panel: Protein kinase C activity in control, H2O2, and H2O2 plus PDTC treated proximal tubular membranes. B) Upper panel: representative blot of GRK 2. Lower panel: densitometric analysis of GRK 2 protein in the proximal tubular membranes. Pretreatment with PDTC abolished H2O2-mediated increase in PKC activity and subsequent membranous GRK2 translocation. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle using One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test (mean ± SEM; n=3-4).

Role of NF-κB in H2O2-mediated renal D1 receptor hyperserine-phosphorylation and defective D1 receptor-G-protein coupling

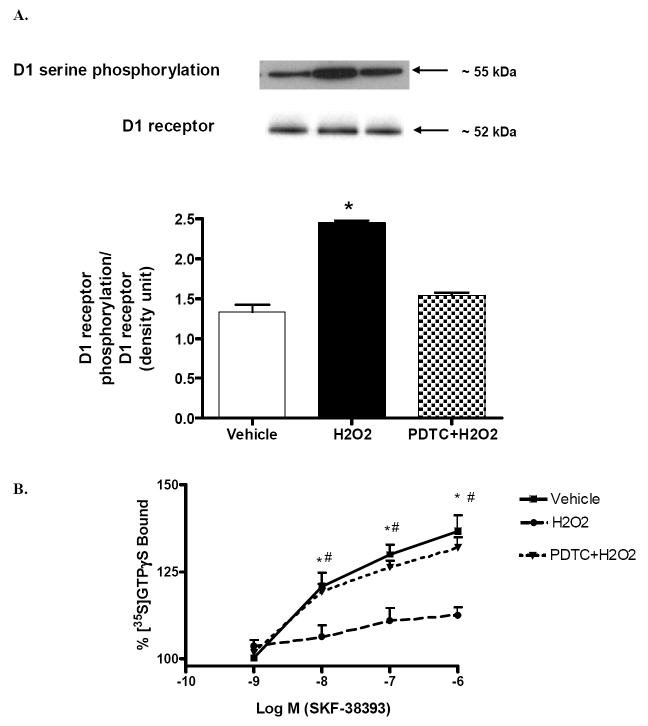

In the renal proximal tubular membranes, H2O2 (20 min/50 μM) treatment caused hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors compared to vehicle (Fig 4A). Pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC (10min/25 μM), prevented H2O2-mediated phosphorylation of D1 receptors (Fig 4A). These results suggest a role of NF-κB in oxidative stress-induced hyperphosphorylation of renal D1 receptors.

Figure 4. NF-κB activation is responsible for H2O2-mediated hyperserine-phosphorylation and defective D1 receptor-G-protein coupling in the renal proximal tubular membranes.

A) Proximal tubular cell membranes were used for immunoprecipitation of D1 receptors. Immunoprecipitated samples were then used for immunoblotting of serinephosphorylated D1 receptors and total D1 receptor proteins. Upper panel: representative immunoblots of serine-phosphorylated D1 receptors and total D1 receptor proteins. Lower panel: densitometric analysis of serine-phosphorylated D1 receptor protein, normalized to immunoprecipitated D1 receptor protein density. Pretreatment with PDTC prevented H2O2-induced hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors. *P < 0.05 compared with Vehicle using One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. B) Proximal tubular membranes from all 3 groups were incubated with [35S] GTPγS, in the presence and absence of SKF-38393 (10-9-10-6 mol/l). Pretreatment with PDTC restored D1 receptor G-protein coupling in the proximal tubular membranes of SD rats. *P < 0.05 compared with H2O2 using One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. #P < 0.05 from 10-8 SKF 38393 using Student’s unpaired t test. (mean ± SEM; n=3).

In vehicle-treated proximal tubular membranes, SKF-38393, a D1 receptor agonist, significantly stimulated D1 receptor- G-protein coupling as evidenced in a concentration dependent increase in GTPγS binding (Fig 4B). SKF-38393 failed to stimulate D1 receptor-G-protein coupling in H2O2-treated proximal tubular membranes (Fig 4B). Pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC (10min/25 μM), restored the ability of SKF-38393 to stimulate GTPγS binding (Fig 4B). PDTC alone did not affect the ability of SKF 38393 (1μM) to stimulate GTPγS binding (129±3.9% increase from vehicle). This suggests a role of NF-κB in H2O2-mediated defective renal D1 receptor G-protein coupling in the proximal tubular membranes.

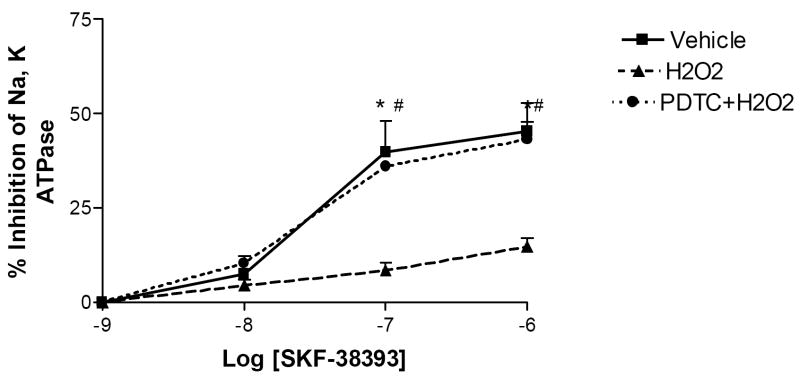

Role of NF-κB in H2O2- induced impairment in SKF-38393 -mediated inhibition of Na-K-ATPase activity

SKF-38393, a D1 receptor agonist, significantly inhibited the Na-K-ATPase activity in vehicle-treated renal proximal tubules but did not produce any effect in H2O2-treated PT (Fig 5). Pretreatment with NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC (10min/25 μM), restored the ability of SKF-38393 to inhibit the Na-K-ATPase activity in H2O2-treated PT to the level seen in vehicle-treated PT (Fig 5). PDTC alone did not affect the ability of SKF 38393 (1μM) to inhibit Na, K-ATPase (41±3.2% decrease from vehicle).

Figure 5. Role of NF-κB in H2O2 induced impairment in SKF-38393 -mediated inhibition of Na-K-ATPase activity in the renal proximal tubules.

Proximal tubular suspensions were incubated with SKF-38393 (10-9-10-6 mol/L) at 37°C for 15 minutes. Ouabain sensitive Na, K-ATPase (NKA) activity was measured as described in Methods. Pretreatment with PDTC restored the ability of D1 receptor agonist to inhibit NKA. *P < 0.05 compared with H2O2 using One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test (mean ± SEM; n=3). #P < 0.05 from 10-8 SKF 38393 using Student’s unpaired t test.

DISCUSSION

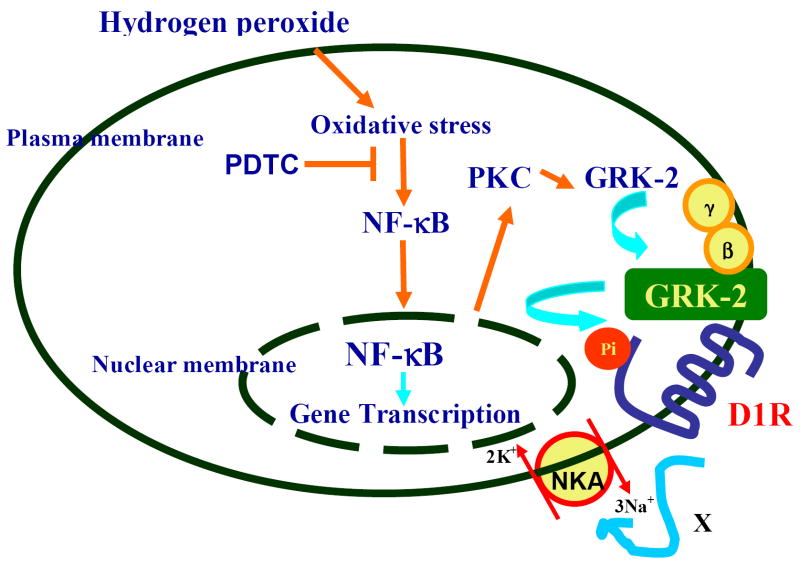

Oxidative stress, present in aging, hypertension, and diabetes contributes to D1 receptor G protein uncoupling and diminished natriuretic response to dopamine receptor activation (5-7, 13-15). Recently, we reported that H2O2 increases PKC activity, which causes membranous translocation of GRK 2. This in turn resulted in hyper-serine phosphorylation of D1 receptors and their uncoupling from G-proteins in the proximal tubular epithelial cells (13). Redox- sensitive NF-κB is increased in states of oxidative stress and regulates the expression of many cellular signaling molecules (16). However, it is not known whether NF-κB plays a role in oxidative stress-induced defective renal dopamine D1 receptor signaling. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the involvement of NF-κB in causing D1 receptor dysfunction in the renal proximal tubules of Sprague Dawley rats. In our study, H2O2 caused nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which triggered the activation of PKC, and subsequent translocation of GRK 2 to the proximal tubular membranes. This resulted in hyper-serine phosphorylation of D1 receptors, D1 receptor-G-protein uncoupling, and decreased D1 receptor activation-mediated inhibition of Na, KATPase activity. Interestingly, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), an NF-κB inhibitor, prevented D1 receptor dysfunction caused by H2O2 by blocking the increase in PKC activity and preventing membranous translocation of GRK 2, as well as hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors, and restoring D1 receptor G-protein coupling. The functional consequence of these changes was restoration in the ability of SKF 38393 to inhibit Na, K-ATPase activity (summarized in figure 6).

Figure 6. A diagrammatic representation of the role of NF-κB in oxidative stress induced renal D1 receptor G-protein uncoupling and loss of functional response to D1 receptor activation.

H2O2 induces the translocation of NF-κB from the cytosol to the nucleus. NF-κB increases PKC activity, which in turn, causes translocation of GRK 2 to the membrane. GRK 2 phosphorylates D1 receptors (D1R) preventing D1 receptor-G-protein coupling. The functional consequence is the inability of D1 receptor agonist to inhibit the Na-K-ATPase (NKA) activity (denoted by X). Treatment with PDTC, while inhibiting NF-κB nuclear translocation, also prevents PKC activity and GRK 2 membranous translocation; and therefore, restores D1 receptor-G-protein coupling and D1 receptor agonist-mediated inhibition of the Na-K-ATPase activity.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to act as second messengers and cause activation of several transcription factors, including NF-κB (24). In particular, the ability of the oxidant, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to activate NF-κB has been demonstrated in many cell lines, including LNCaP cells, a human prostate cancer cell line (25), murine macrophage B10R cells (26), human myeloid KBM-5 (27), and many others. Therefore, it is possible that H2O2 stimulated the (ubiquitously-expressed) NF-κB in the renal proximal tubules of Sprague Dawley rats. Both, our western blotting and immunofluorescence studies depicted H2O2-mediated translocation of NF-κB to nuclei fractions of renal proximal tubules. Interestingly, treatment either with PDTC, an NF-κB inhibitor, or ascorbic acid, an antioxidant, abolished H2O2-mediated activation of NF-κB (Figures 1 and 2). Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate has been used previously to inhibit the translocation of NF-κB. For example, in vivo administration of PDTC reduced the extent of systemic hypertension and inflammation in rats (28). In addition, PDTC has been reported to attenuate the development of acute and chronic inflammation in an animal model of arthritis (29), and to protect against brain ischemia in Wistar rats (30).

Our results also suggest that NF-κB is involved in H2O2-induced activation of PKC in the renal PT. This is supported by the finding that PDTC attenuated H2O2-mediated increase in PKC activity (Figure 3A). Oxidative stress-mediated activation of NF-κB and PKC has been shown in mesangial cells and a role of this pathway was suggested in diabetic nephropathy (31). Another study shows that ROS-mediated increase in PKC δ activity plays a role in the pathway leading to apoptosis and cell growth arrest (32). Also, PKCα-mediated chemotaxis of neutrophils requires increased NF-κB activity in mouse skin in vivo (33). In addition, H2O2-induced activation of NF-κB-dependent gene expressions have been reported in many studies (34). Therefore, increased oxidative stress in H2O2-treated PT may have caused nuclear translocation of NF-κB leading to activation of PKC in the renal PT of SD rats.

G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) play an important role in regulating G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling by their ability to phosphorylate and desensitize agonist occupied or agonist unoccupied receptors (11). For example, GRK2 has been shown to phosphorylate D1 receptors causing a reduction in the agonist affinity in embryonic kidney cells (12). GRK 4 also participates in the regulation of D1 receptors in the renal proximal tubule cells from humans (35). An increase in the basal activity of GRK4 has been reported in the proximal tubules from spontaneously hypertensive rats and hypertensive subjects (36). Our results show H2O2 increases the membranous translocation of GRK2 to the proximal tubular membranes of SD rats. These results are consistent with our previous observation of increased translocation of GRK2 to the proximal tubular membranes in animal models of type 1 and 2 diabetes, which exhibit oxidative stress (14,15). Interestingly, pretreatment with PDTC prevented H2O2-mediated membranous translocation of GRK2, suggesting that this translocation is mediated via NF-κB (Figure 3B).

Our results, consistent with our previous study in the primary culture of renal PT (13), show that H2O2 increased dopamine D1 receptor phosphorylation in the proximal tubular membranes of SD rats, which led to D1 receptor-G-protein uncoupling (Figure 4A and 4B). We suggest that H2O2-induced GRK2 membranous translocation caused hyperserine-phosphorylation of D1 receptors, resulting in D1 receptor G-protein uncoupling. Interestingly, NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC, abolished D1 receptor hyperphosphorylation and restored the coupling of D1 receptors with G-proteins (Figure 4A and 4B). The functional consequence of these changes was the restoration of SKF-38393, a D1 receptor agonist-mediated inhibition of Na, K-ATPase activity in the renal PT of SD rats (Figure 5).

In summary, this is the first study to report a role of the nuclear factor NF-κB in oxidative stress-induced defective renal dopamine D1 receptor signaling in Sprague Dawley rats. Hydrogen peroxide triggered the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which caused increase in PKC activity and subsequent translocation of GRK2 to renal proximal tubular membranes of SD rats. This resulted in hyperphosphorylation of D1 receptors and their uncoupling from G protein, leading to decreased D1 receptor agonist-mediated inhibition of Na, K-ATPase activity. Treatment with PDTC, an NF-κB inhibitor, prevented H2O2-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and restored D1 receptor-G-protein coupling and function (Figure 6). Therefore, NF-κB may represent a potential target against defective renal D1 receptor signaling in models associated with oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG 25056 from the National Institute on Aging. The study protocol involving the use and care of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Abbreviations

- GRKs

G-protein-coupled receptor kinases

- GRK 2

G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NKA

Na, K-ATPase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PDTC

pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

- PT

proximal tubules

- SD

Sprague-Dawley

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- [35S]GTPγS

guanosine 5’-(γ-thio)triphosphate[35S]

- SKF-38393

(±)-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-(1H)-3-benzazepine-7,8-diol hydrochloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jose PA, Eisner GM, Felder RA. Renal dopamine receptors in health and hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:149–182. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aperia AC. Intrarenal dopamine: a key signal in the interactive regulation of sodium metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:621–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegde SS, Jadhav AL, Lokhandwala MF. Role of kidney dopamine in the natriuretic response to volume expansion in rats. Hypertension. 1989;13:828–834. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Renal dopamine receptor function in hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;32:187–197. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beheray S, Kansra V, Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Diminished natriuretic response to dopamine in old rats is due to an impaired D1-like receptor-signaling pathway. Kidney Int. 2000;58:712–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Beach RE, Lokhandwala MF. Dopamine fails to inhibit renal tubular sodium pump in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1993;21:364–372. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marwaha A, Banday AA, Lokhandwala MF. Reduced renal dopamine D1 receptor function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F451–457. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00227.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taher MM, Garcia JG, Natarajan V. Hydroperoxide-induced diacylglycerol formation and protein kinase C activation in vascular endothelial cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303:260–266. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schupp-Koistinen I, Moldues P, Bergman T, Cotgreave IA. S-thiolation of human endothelial cell glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase after hydrogen peroxide treatment. Eur J Biochem. 1994;227:1033–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asghar M, Lokhandwala MF. Antioxidant supplementation normalizes elevated protein kinase C activity in the proximal tubules of old rats. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:270–275. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:9–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiberi M, Nash SR, Bertrand L, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Differential regulation of dopamine D1A receptor responsiveness by various G-protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3771–3778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asghar M, Banday A, Fardoun R, Lokhandwala MF. Hydrogen peroxide causes uncoupling of dopamine D1-like receptors from G proteins via a mechanism involving protein kinase C and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banday A, Marwaha A, Tallam L, Lokhandwala MF. Tempol reduces oxidative stress, improves insulin sensitivity, decreases renal dopamine D1 receptor hyperphosphorylation and restores D1 receptor-G protein coupling and function in obese Zucker rats. Diabetes. 2005;54:2219–26. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marwaha A, Lokhandwala MF. Tempol reduces oxidative stress and restores renal dopamine D1-like receptor G-protein coupling and function in hyperglycemic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F58–66. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00362.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zingarelli B. Nuclear factor-κB. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S414–416. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186079.88909.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen R, Baltimore D. Inducibility of kappa immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein NF-κB by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell. 1986;47:921–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zingarelli B, Sheehan M, Wong HR. Nuclear factor-κB as a therapeutic target in critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S105–111. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cammano J, Hunter CA. NF-κB family of transcription factors: central regulators of innate and adaptive immune functions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:414–429. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.414-429.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brismar H, Asghar M, Carey RM, Greengard PM, Aperia A. Dopamine-induced recruitment of dopamine D1 receptor to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5573–5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanada H, Jose PA, Hazen-Martin D, Yu PY, Xu J, Bruns DE, Phipps J, Carey RM, Felder RA. Dopamine-1 receptor coupling defect in renal proximal tubule cells in hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:1036–1042. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.4.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asghar M, Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Higher basal serine phosphorylation of D1 receptors in proximal tubules of old Fischer 344 rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F350–F355. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00361.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Renal dopamine DA1 receptor coupling with GS and Gq/11 proteins in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1997;272:F339–F346. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baeuerle PA, Rupec RA, Pahl HL. Reactive oxygen intermediates as second messengers of general pathogen response. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1996;44:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Johnson G, Stebler B, Keller EV. Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-κB and the interleukin-6 promoter through NF-κB-inducing kinase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:493–504. doi: 10.1089/15230860152409121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaramillo M, Olivier M. Hydrogen peroxide induces murine macrophage chemokine gene transcription via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and syclic 5’ monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent pathways:involvement of NF-κB, activator protein 1, and cAMP response element binding protein. J Immunol. 2002;160:7026–7038. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takada Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Kundu G, Mahaabeleshwar GH, Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-κB through tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB alpha and serine phosphorylation of p65. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24233–24241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu SF, Ye X, Malik AB. In vivo inhibition of nuclear factor -κB activation prevents inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and systemic hypotension in a rat model of septic shock. J Immunol. 1997;159:3976–3983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuzzocrea S, Chatterjee PK, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Serraino I, Britti D, Mazzullo G, Caputi A, Thiemermann C. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate attenuates the development of acute and chronic inflammation. British J Pharmacol. 2002;135:496–510. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Nurmi A, Vartiainen N, Pihlaja R, Goldsteins G, Yrjanheikki J, Koistinaho J. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits translocation of NF-kappa B in neurons and protects against brain ischeamia with a wide therapeutic time window. J Neurochemi. 2004;91:755–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lal MA, Brismar H, Eklof AC, Aprecia A. Role of oxidative stress in advanced glycation and product induced mesangial cell activation. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2006–2014. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domenicotto C, Marengo B, Nitti M, Verzola D, Garibotto G, Cottalaso D, Poli G, Melloni E, Pronzato MA, Marinari UM. A novel role of protein kinase C-delta in cell signaling triggered by glutathione depletion. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cataisson C, Pearson AJ, Torgerson S, Nedospasov SA, Yuspa SH. Protein kinase C alpha-mediated chemotaxis of neutophils requires NF-κB activity but is independent of TNF alpha signaling in mouse skin in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:1686–1692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen G, Jeong W, Hu R, Kong AT. Regulation of Nrf2, NF-κB, and AP-1 signaling pathways by chemoprotective agents. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1648–1663. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe H, Xu J, Bengra C, Jose PA, Felder RA. Desensitization of human D1 dopamine receptors by G-protein coupled receptor kinase-4. Kidney Intl. 2002;62:790–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felder RA, Sanada H, Xu J, Yu PY, Wang Z, Watanabe H, Asico LD, Wang W, Zheng S, Yamaguchi I, Williams SM, Gainer J, Brown NJ, Hazen-Martin D, Wong LJ, Robillard JE, Carey RM, Eisner GM, Jose PA. G proteincoupled receptor kinase 4 gene variants in human essential hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3872–3877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062694599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]