Abstract

Introduction

The children of mentally ill parents have a higher risk of developing mental illnesses themselves over the course of their lives. This known risk must be taken into account in the practical provision of health care.

Methods

Selective literature review.

Results

The increased psychiatric risk for children of mentally ill parents is due partly to genetic influences and partly to an impairment of the parent-child interaction because of the parent’s illness. Furthermore, adverse factors are more frequent in these families, as well as a higher risk for child abuse. Genetic and psychosocial factors interact with one another. For example, genetic factors moderate environmental effects; that is, the effect of adverse environmental factors depends on the genetic substrate.

Discussion

Preventive measures for children of mentally ill parents urgently need improvement. In this article, positively evaluated programs of preventive measures are discussed. Essential prerequisites for success include appropriate, specialized treatment of the parental illness, psychoeducative measures, and special support (e.g. self-help groups) as indicated by the family’s particular needs.

Keywords: mental illness, parent-child relationship, pediatric illness, family medicine, prevention

A number of recent cases in which children were killed by a mentally ill father or mother have attracted much attention and a strong emotional response from the public. In Germany, about two children under the age of 15 die, on average, each week as the result of violence, physical abuse, and neglect (1). Mental illness in the parents is a major risk factor for such tragic events. Yet abuse and neglect with deadly consequences are merely the tip of the iceberg: according to our current scientific knowledge, the children of mentally ill parents are often subject to especially severe stresses and limitations, and these children are themselves at a greater than normal risk of developing a mental illness (2, 3).

The children of mentally ill parents are a special risk group with regard to the development of mental illness. In studies of children and adolescents who make use of psychiatric services, it has been found that up to half of these mentally ill children or adolescents live with a mentally ill parent (table 1). Substance-related disorders, in particular, are much more common among the parents of mentally ill children (with a frequency of about 20%) than in the general population (about 4.5%) (4). These figures vary depending on the diagnosis carried by the child: especially high rates of substance-related disorders are seen in the parents of children with disturbances of social behavior.

Table 1. The frequency of different types of mental illness and related conditions among the parents of patients undergoing treatment in a child and adolescent psychiatric service.

| Type of mental illness or related condition | Fathers (n = 978) n (%) | Mothers (n = 1035) n (%) | Parents of either sex (n = 1083) n (%) |

| Oligophrenia | 7 (0.7) | 10 (1.0) | 15 (1.4) |

| Epilepsy | 3 (0.3) | 10 (1.0) | 13 (1.2) |

| Schizophrenia | 11 (1.1) | 21 (2.0) | 31 (2.9) |

| Affective disorders (depression/mania) | 46 (4.7) | 92 (8.9) | 129 (11.9) |

| Neurotic and somatoform disorders | 43 (4.4) | 109 (10.5) | 141 (13.0) |

| Hyperkinetic syndrome | 11 (1.1) | 10 (1.0) | 18 (1.7) |

| Dyslexia | 9 (0.9) | 15 (1.4) | 23 (2.1) |

| Suicidal behavior | 18 (1.8) | 23 (2.2) | 39 (3.6) |

| Substance-related disorders: alcoholism, drug abuse | 186 (19.0) | 72 (7.0) | 224 (20.7) |

| Criminality | 39 (4.0) | 7 (0.7) | 43 (4.0) |

| Other types of mental illness | 36 (3.7) | 37 (3.6) | 69 (6.4) |

| TOTAL: All psychiatrically relevant conditions | 332 (33.9) | 334 (32.3) | 523 (48.3) |

These data were derived from the complete inpatient population of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of the Philipps-Universität, Marburg (Germany) from 1998 to 2002. They were obtained by systematic, direct questioning of the parents about each of the listed types of mental illness with a documentation questionnaire. Data acquisition was performed as described in the "Basisdokumentation der Klinik für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie der Philipps-Universität, Marburg, Version 01/03“ (ed.: H. Remschmidt), which is an expanded version of the basic documentation sheets of the German professional societies for child and adolescent psychiatry. The latter can be found on the Internet at http://www.bkjpp.de/files/BADO 3.PDF

The elevated risk of mental illness among the children of mentally ill parents

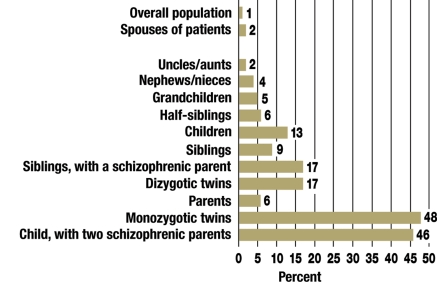

The probability of developing a particular type of mental illness is higher when a biological parent or other relative has the same condition. Such associations have been extensively investigated in twin, adoption, and family studies, and they can be conveniently illustrated here with the study findings regarding schizophrenia (figure 1). The lifetime risk of developing schizophrenia is about 1% in the general population, but more than ten times higher if a parent suffers from the disease. If both parents are schizophrenic, the lifetime risk of schizophrenia in the children is about 40%. The data in figure 1 cannot be directly compared to the figures in table 1, because figure 1 exclusively concerns schizophrenia.

Figure 1.

The lifetime risk of schizophrenia is correlated with the degree of relationship to the patient (first-degree relatives are at greater risk than second-degree relatives) (5, 6).

Similarly, for mental illnesses other than schizophrenia, the children of affected parents are at markedly increased risk of developing the disease. Thus, children of depressed parents have a much higher risk than the general population of developing an affective disorder (table 2). A number of factors play a role in the elevation of risk, including the type of illness, the severity of the parental illness, and the age at onset of the disease. For example, a family history of mental illnesses with a severe and recurrent course elevates the risk particularly strongly.

Table 2. The association of parental depression with depressive conditions in children and adolescents.

| Classification by status of the parents: | Conditions in children and adolescents: | ||

| Major depression (%) | Dysthymia (%) | Bipolar disorder (%) | |

| 0 parents with major depression | 12.3 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 1 parent with major depression | 26.1 | 5.3 | 3.2 |

| 2 parents with major depression | 28.5 | 6.8 | 5 |

From: Lieb et al. 2002; simplified from Schulte-Körne and Allgaier (7)

Alongside these figures, it should also be pointed out that the children of mentally ill parents are at elevated risk not only of the specific mental illness from which their parents suffer, but also of mental illness in general. Meta-analyses have revealed that about 61% of the children of parents with major depression develop a mental illness over the course of childhood and adolescence. The probability of mental illness in childhood and adolescence is elevated more than fourfold over that of the normal population (2, 8).

Genetic and environmental factors

The fact that the degree of risk elevation for schizophrenia depends on the nearness of the family relationship to an affected person, as seen in figure 1, indicates that the risk of illness is due, at least in part, to genetic factors. This is true not just for schizophrenia, but to a greater or lesser extent for all other types of mental illness as well.

In addition to genetic loading, another reason for the elevated risk among the children of mentally ill parents may be that the parents’ behavior toward the child is adversely affected by the disease. Multiple studies on this subject have unanimously shown that the interaction between depressed mothers and their children is severely impaired (9, 10).

Infancy and early childhood

The following alterations of parental behavior affect the child during infancy and early childhood:

Depression reduces maternal empathy and emotional availability.

The mother’s ability to perceive the child’s signals, interpret them correctly, and respond promptly and appropriately is limited.

Maternal eye contact, smiling, speaking, imitating, caressing, and interactive games are all reduced compared to the normal situation.

The kindergarten and elementary school years

The following alterations of parental behavior commonly affect the child in this developmental phase:

Mothers tend to perceive their children as being more than normally difficult.

Verbal communication is reduced.

In the context of new developmental tasks, mothers find it difficult to control their children’s behavior and to set boundaries.

Mothers sometimes react with excessive anxiety and restrict their children’s expansive tendencies too much (vacillation between permissive and controlling child-rearing styles).

Positive comments that reinforce the child’s self-esteem are more rarely expressed.

Later childhood and adolescence

In this developmental phase, the behavioral effects of parental mental illness manifest themselves in yet another way: often, the child is required to assume tasks and responsibilities that are normally borne by parents and other adults ("parentification"). This can take the following forms:

The child is drawn into parental problems and conflicts (diffuse borders between the generations).

Because of the parental illness, the child’s identification with his or her parents is limited (attenuated role-model function of the parents).

The parents are unable to support the child as he or she tries to perform age-specific developmental tasks (particularly competence acquisition, independence, and the development of autonomy).

In sum, the parents’ behavior toward the child, the parent-child interaction, and the parent-child relationship can all be disturbed by parental mental illness over the entire course of the child’s development.

Increased psychosocial stress

Furthermore, nearly all of the major sources of psychosocial stress that raise a child’s risk of mental illness are overrepresented in families with a mentally ill parent. In other words, the trait "mental illness in a parent" is positively correlated with many other psychosocial stress factors; it is thus a "core trait" whose presence implies a significant disturbance of the child’s developmental milieu. Accordingly, for example, the children of mentally ill parents are exposed particularly often to the following familial risk factors (11):

Socioeconomic and sociocultural risk factors such as poverty, inadequate housing, marginal social status, and cultural discrimination of the family

Low educational and occupational status of the parents, including possible unemployment

Loss of persons to whom the child is emotionally close, particularly a parent

A two to five times higher risk of neglect and physical and sexual abuse.

The vulnerability-stress model

Now that research has demonstrated the importance of both genetic and psychosocial factors for the development of mental illness, it would be desirable to gain a clearer picture of the manner in which these factors interact. A number of studies on the interaction of genetic and environmental factors have been published in recent years.

Caspi et al. (12), for example, considered the interaction of genetic predisposition and environmental stress that leads to depression. They studied more than 800 persons, dividing them into three groups depending on their particular genetic profile with respect to the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR. The groups of subjects with two short alleles (s/s), with one short and one long allele (s/l), and with two long alleles (l/l) were analyzed separately. The rationale for considering these subgroups of the study population was that the short allele is known to be associated with a lesser availability of serotonin than the long allele (13), while, according to the monoamine deficiency hypothesis, a disturbance of serotonin and norepinephrine metabolism is held to be the main cause of depression. The number of highly stressful life events each subject had experienced in his or her life to date was also determined. These data were used to analyze the effects of heredity and of life events on the probability of the later development of depressive manifestations.

It was found that persons in each of the three genetically defined groups reacted very differently to stressful events in their life history. In the s/s group, the probability of a depressive episode rose dramatically as a function of the number of such events; on the other hand, in the l/l group, there were only small differences between subjects, and these were independent of the number of stressful events. Analogous results were obtained with respect to the effect of stressful events on suicide attempts and the effect of abuse in childhood on later depressive episodes (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The association between the number of stressful life events and the probability of having a depressive episode in three genetically distinct groups, as reported by Caspi et al. (12). The three groups differ with respect to the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR): s/s = probands with two short alleles, s/l = probands with one short and one long allele, l/l = probands with two long alleles. From: Caspi A et al.: Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003; 301:386–9, with the kind permission of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, New York.

These findings show that both types of factors, genetic and environmental, must be taken into account if the causal mechanisms are to be adequately described. Genetic predisposition determines, in part, whether certain life events will have a pathogenic effect; it thus modulates the effect of the environmental factors.

One still occasionally encounters the prejudiced notions that genetic factors can only be altered by biological methods, if at all – e.g., by gene therapy or medications – and that psychosocial influences have a lesser effect than genetic ones. Both of these notions are false. The study data show, rather, that it is precisely those individuals whose genetically based vulnerability is highest who react the most strongly to environmental influences, in both the positive and the negative direction.

Very recently, similar results have been obtained in Germany as well. The Mannheim longitudinal studies revealed significant interactive effects between genetic traits and family living circumstances. Young people with a genetic vulnerability (dopamine transporter gene DAT1) to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) who grew up in adverse family circumstances suffered to a more marked extent from inattentiveness and from hyperactivity/impulsiveness than young people with other genotypes, or than young people who grew up in more favorable circumstances (14).

The subjective dimension

In any well-founded preventive strategy, an attempt must be made to grasp the concrete problems that parents and children struggle with in the way that these persons themselves experience them. Familiarity with the subjective perspective is needed if the treating personnel are to comprehend how (i.e., in what ways and through which "mechanisms") these stress factors lead to mental problems in the children; this sort of familiarity also provides an avenue of therapeutic approach to the affected young people. In a number of interview studies, the subjective experience of the children was qualitatively analyzed. The interviews were often carried out with adults who had grown up with a mentally ill parent at home. The most important problems that the children of mentally ill parents themselves mentioned were the following (3):

Disorientation: The children are anxious and confused because they cannot categorize or comprehend their parents’ problems.

Guilt feelings: The children consider themselves guilty of causing their parents’ mental problems: "Mommy is sick/mixed up/sad because I was bad/because I didn’t take good enough care of her."

Inability to communicate: The children have the (usually correct) impression that they are not allowed to discuss their family problems with anyone. They are afraid of giving their parents away (letting others know that the parents are doing something "bad") if they speak to persons outside the family.

Isolation: The children do not know to whom they can turn with their problems and have no one to talk to about them. In other words, they are abandoned to themselves.

The children’s reactions to these conflict situations are highly variable and can swing rapidly from one extreme to another. No single reaction pattern can be called typical for the children of mentally ill parents; rather, there are a number of different, sometimes diametrically opposed, reaction patterns or coping strategies. Often, one sibling will use fleeing from the family (for example) as a reaction pattern, while another reacts in an opposite manner, e.g., by assuming a high degree of responsibility. When the children themselves have mental disorders, the clinical manifestations can be highly variable as well. There is thus no single group of abnormalities or mental disorders that would be typical of the children of mentally ill parents.

Preventive measures

Time and again, one sees children who are able to overcome these stresses without any apparent damage, even under the least favorable environmental circumstances. The concept of resilience indicates that many individuals undergo a relatively good mental development even though they have been exposed to risk factors that can often cause serious illness. The goal of resilience research is to identify the mechanisms that explain this variability of developmental course, and thereby to point the way to effective preventive strategies.

Preventive strategies for the risk group that consists of the children of mentally ill parents must involve reducing the psychosocial stresses to which they are frequently subject, as well as reinforcing individual and societal protective factors in order to enable normal development. To date, however, there are very few preventive strategies for this risk group whose effectiveness has been tested in randomized, controlled studies (15).

Different preventive strategies are currently available for different age groups:

For infants and small children, one can employ the interaction-centered mother-child therapies (0 to 3 years) that were developed for the treatment of behavioral disorders and that have been empirically tested with encouraging results (16).

For children in elementary school and younger adolescents, a successfully tested preventive program is available that was developed particularly for families with a mentally ill parent (2, 8). This program can be adapted for use with preschool children.

Furthermore, for children in elementary school and younger adolescents, tested preventive programs are available that are directed primarily at these children and adolescents themselves, though they may contain a parent module as well (17).

The study data and clinical experience to date provide a relatively clear impression of which measures are truly useful and effective:

The basis of all preventive strategies is an effective treatment of the parental illness in qualified professional hands. The mental abnormalities of the children can be reduced if the parental illness is successfully treated.

The second indispensable element of prevention consists of psycho-educative interventions such as are performed, for example, in the program of Beardslee (education about the illness, application of this information to the individual case, and encouragement of open communication about the illness in the family).

The third component of prevention consists of special aids that should be adapted to each family’s particular situation, and that should be used only when specifically indicated. These include psychiatric and psychotherapeutic assistance as well as social-pedagogical aids, e.g., social-pedagogical family assistance or special offerings of other types, such as groups for the children of mentally ill parents.

It is of central importance for successful prevention that the experts and institutions providing help to these children and adolescents – such as schools, departments of youth services, psychiatrists, child and adolescent psychiatrists, psychological psychotherapists, and child and adolescent psychotherapists – should all work in close collaboration. Teachers play an especially important role, as they often are the first to notice that the child has a problem and can then, with the parents’ permission, arrange for further help to be provided.

Fortunately, there have been many new initiatives in Germany in recent years aimed at providing preventive assistance to the children of mentally ill parents (15, 18). Further information can be found, for example, on the following (German-language) websites: www.netz-und-boden.de; www.kipkel.de or www.familienberatungszentrum.de/partnerschaft.htm; www.mutter-kind-behandlung.de; www.diakonie-wuerzburg.de.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Trautmann-Villalba P, Hornstein C. Tötung des eigenen Kindes. Nervenarzt. 2007;78:1290–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00115-007-2355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beardslee WR. Protecting the children and strengthening the family. Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Co; 2002. Out of the darkened room. When a parent is depressed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattejat F. Kinder mit psychisch kranken Eltern. Was wir wissen, und was zu tun ist. In: Mattejat F, Lisofsky B, editors. Nicht von schlechten Eltern. 5th edition. Bonn: Psychiatrie Verlag; 2005. pp. 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundespsychotherapeutenkammer. BPtK-Newsletter. 2007 Feb;Volume I/2007:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman II. The Origins of Madness. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1991. Schizophrenia Genesis. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. Genetics of schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2005;4:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulte-Körne G, Allgaier K. Genetik depressiver Störungen. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2008;36:27–43. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917.36.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TRG, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112:119–131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattejat F. Kinder depressiver Eltern. In: Braun-Scharm H, editor. Depressionen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2002. pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papousek M. Wochenbettdepressionen und ihre Auswirkungen auf die kindliche Entwicklung. In: Braun-Scharm H, editor. Depressionen und komorbide Störungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 2002. pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ihle W, Esser G, Martin MH, Blanz B, Reis O, Meyer-Probst B. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for mental disorders in young adults and their parents in east and west Germany. Am Behav Sci. 2001;44:1918–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Müller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274:1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laucht M, Skowronek MH, Becker K. Interacting effects of the dopamine Transporter Gene and psychosocial adversity on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms among 15-year-olds from a high-risk community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:585–590. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattejat F, Lisofsky B, editors. Nicht von schlechten Eltern. Kinder psychisch Kranker. 5th edition. Bonn: Psychiatrie-Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wortmann-Fleischer S, Downing G, Hornstein C. Postpartale psychische Störungen. Ein interaktionszentrierter Therapieleitfaden. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essau CA, Conradt J. Freunde: Prävention von Angst und Depression. München: Reinhardt; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenz A. Interventionen bei Kindern psychisch kranker Eltern. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2007. [Google Scholar]